John Cassidy's Blog, page 99

April 4, 2012

Masters Preview: Can Tiger Woods Win It All, Again?

It's the rare mega sporting event that lives up to its billing. The third Ali-Frazier fight, known as the "Thrilla in Manila," managed it. So did the "Miracle on Ice," the showdown at the 1980 Winter Olympics between Team U.S.A. and the U.S.S.R. The 2004 A.L.C.S. between the Yankees and Red Sox provides a more recent example. But all too often—c.f. every soccer World Cup final in recent memory—the hype overshadows the action.

For fans of golf, this year's Masters tournament, which begins tomorrow in Augusta, Georgia, has the potential to join the list of great sporting matchups. And for once, the interest in the outcome won't be confined to we sick individuals who have become addicted to the strange highs (and lows) of hitting a little white ball with a long metal stick. This is a story line that goes beyond sports and appeals to something more primeval: Can the legendary but battle-scarred warrior king, whom fate has risen up and struck down, return to the battlefield in triumph? Or will he fall to one of the host of pretenders to his crown who have appeared during his lengthy absence?

At the risk of putting the hex on Tiger Woods's chances, I think he is a justifiable favorite. That doesn't mean he will win. Golf is a game where even the very greatest lose much more often than they win. And during the past few years, the gap in technique and ability between Woods and his rivals has narrowed to the extent that many experts (and professional players) believe it is now virtually non-existent. But given Tiger's recent return to form and his love of the golf course, it's hard to see him not competing all the way to Sunday evening, when the tournament will come to its traditional climax on CBS, which has broadcast it every year since 1956, when Jack Burke, Jr., beat Ken Venturi by a single shot.

Here then, for the benefit of golf nuts and casual observers alike, is a quick F.A.Q. that is meant to serve as a viewing guide and handicapping sheet.

Q: Is Tiger really back? Only a couple of months ago, most people appeared to have written him off?

A: Yes, he is back. In winning Arnold Palmer's tournament at Bay Hill a couple of weeks ago, he looked like the Tiger Woods we all knew, striping the ball down the middle of fairway, swatting it onto the green, and holing putts. Last year, he appeared to have lost the ability to do all of these things. His driving, in particular, was so wayward that he was a constant threat to the crowds that follow him around the course. But after working with a new coach, Sean Foley, he has rediscovered how to hit the ball straight, while also hitting it farther. For a golfer, that is like finding gold. And once Tiger started hitting the ball where he could find it, the other aspects of his game gradually came around. After his victory at Bay Hill, he told his old friend Mark O'Meara, "it felt like old times out there again."

Q: What about the mental aspect? Has Tiger really put all that stuff about cheating on his ex-wife, cavorting with porn stars, and droppings wodges of cash in Last Vegas casinos behind him?

A: Who knows? But as a new book by his former coach, Hank Haney, makes clear, Tiger is a very unusual individual: almost entirely self-centered, incredibly focussed, and largely oblivious to his surroundings, other people included. This egocentric approach to life won't win him any humanitarian awards, but it is perfectly suited to golf. When you are facing an eight-foot putt to save par, there aren't any teammates you can rely on: it's all on you. If anybody can set aside the wreckage of his personal life and perform again at the highest level, it is Tiger. "I learned one thing for sure," he told Haney during his tribulations. "When I play golf again, I'm going to play for myself. I'm not going to play for my Dad, or my Mom, or Mark Steinberg [his agent] or Steve Williams [his former caddie] or Nike [his primary commercial sponsor] or my foundation, or the fans. I'm only going to play for myself."

Q: Apart from Tiger, who are the pre-tournament favorites?

A: There are a number of them. And what makes this weekend so exciting is that all of them are in excellent form. Rory McIlroy, a twenty-two-year-old Northern Irish phenom who now makes his home in Florida, is now the second-ranked player in the world, and in his last three events he hasn't finished out of the top three. Phil Mickelson, Tiger's longtime rival, won earlier this year at Pebble Beach and played well in Houston last week. Luke Donald, a low-key Englishman who is officially the No. 1 player in the world, won in Florida three weeks ago.

All three of these players have demonstrated that they can play well at Augusta, which is a notoriously idiosyncratic golf course—there's not much rough, but there are lots of elevation changes, and fast, subtle greens. Last year, McIlroy was leading going into the final round, only to blow up on the back nine. Mickelson has a fabulous record at Augusta—eleven top-ten finishes in the past thirteen years, including three wins. Donald finished fourth last year, and, like Mickelson, he's got a wonderful short game.

Q: What about some dark horses?

A: The ninety-nine-man field is full of them. Here's half a dozen to look out for: Hunter Mahan, a goateed Californian dude who has already won twice this year, including last week in Houston; Lee Westwood, a wise-cracking Northern Englishman, the No. 3 player in the world, who has come close to winning a number of majors; Bubba Watson, an antic Floridian who hits the ball huge distances and can also bend its trajectory in amazing ways; Nick Watney, another big hitter, a low-key Californian who doesn't have any apparent weaknesses in his game; Steve Stricker, the fifth-ranked player in the world and perhaps the best putter, who is overdue a run at the Masters; and finally Sergio Garcia, the mercurial Spaniard, who has been showing hints of a return to form but is still plagued by occasional putting lapses.

Q: How's the course and the weather forecast?

A: It's been a wet spring in Georgia, and that could be an important factor this week. In a normal year, the greens at Augusta are some of the hardest and fastest in the world. This places a premium on putting skills, but also on accurate approach shots. If you hit your ball into the wrong parts of the green, three-putt bogies (and even four-putt bogies) become a possibility. This year, though, the greens are much softer than normal. After playing a practice round yesterday, Phil Mickelson said "it's just not the same Augusta. It's wet around the greens, and there's no fear of the course."

Q: Who do these conditions favor?

A: Everybody. Today's professional golfers are so good that on any course where the greens are soft they can fire at the pins and make lots of birdies. Mickelson is predicting low scores this week, and he says the conditions could produce a surprise winner. "I think there's a very good chance that a young player—an inexperienced, fearless player that attacks this golf course—can win if you don't need to show it the proper respect." Of course, Mickelson, Woods and the other top players can also play fearless, attack-the-pin golf. From a viewing perspective, the prospect of lots of birdies and low scores is very appealing. One of the drawbacks of the Masters in recent years is that the course had been lengthened so much, and made so difficult, that birdies have become a rarity. In this week's rain-softened conditions, the course could play like it did in the sixties and seventies, when players like Jack Nicklaus, Johnny Miller, and Raymond Floyd would often make a "charge" on the back nine on Sunday.

Q: If I'm watching Tiger on Thursday or Friday, what should I look out for?

A: Two things. First, his drives. Is he hitting it straight off the tee? When he does, he almost always competes for the tournament, and often wins. With his great power, Tiger can make virtually any hole at August a potential birdie hole. But he has to put his tee ball in a position from which he can attack. Second, look closely at his putting. In his prime, what really distinguished him from his rivals wasn't his long shots—awesome as they were—but his ability to hole out practically everything, especially when he desperately needed to. After his troubles, this uncanny knack seemed to desert him. At last year's Masters, despite being in poor form going in, Tiger fought his way up the leader board and put himself in a position to win. But at the fifteenth on Saturday, with a really low round in his sights, he flubbed a short eagle putt that he would never have missed in his prime. For the first time, I thought he might struggle to come back and win more majors. Since then, his putting has been up and down. In recent weeks, it has looked very solid. This, though, will be its biggest test.

Q: Who's your bettor's pick?

A: I think that the odds of 5/1 and 13/1 respectively for Tiger and Mickelson both present reasonable value. However, I would back them to place, which means you win if they finish in the top five. The odds are lower that way, obviously, but the game is too competitive these days to bank on your man winning. As long shots, I'd point to Martin Kaymer, the unflappable German, at 85/1; Ian Poulter, the brightly-dressed Englishman, at 110/1; and Johnson Wagner, an actual New Yorker—he used to caddy at Hudson National in Westchester—at 180/1. Happy viewing!

Photograph by Timothy A. Clary/AFP/Getty Images.

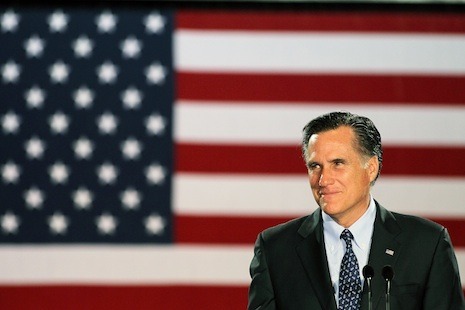

The Reckoning: Romney After Wisconsin

In economics, there is something called Stein's Law, which was coined by the late Herbert Stein, who chaired the Council of Economic Advisers under President Nixon. It says that if something is unsustainable it will eventually come to an end—a truism often forgotten during stock market bubbles and real estate booms. Now, in the political realm, we have Romney's Law: if something is inevitable, it will eventually happen, however little enthusiasm people have for it.

Thus the Mittster's sweep of Maryland, Washington D.C., and Wisconsin, which leaves him, in the eyes of everybody except Rick Santorum (and possibly some members of Santo's immediately family), as the G.O.P. nominee-elect. A couple of days ago, I tried to gin up a little excitement by suggesting that Santorum might conceivably pull off a surprise victory in Wisconsin, but nobody really believed it—not me, not Santorum, who left the dairy state well before the polls closed, and not the Obama re-election campaign, which moved into general election mode a couple of weeks ago, after Romney won in Illinois. As voting was taking place Tuesday, the White House rolled out the President to depict the House G.O.P.'s new budget proposal as "thinly veiled Social Darwinism," and to remind people that Romney had described it as "marvelous."

Who could blame Team Obama for engaging in a blatant bit of electioneering? As Romney said back in January, "politics ain't beanbags," and his endorsement of a proposal that would convert Medicare to a voucher program, slash Medicaid, and give yet more tax cuts to the wealthy is just one of many alarming legacies of his primary campaign. Before he can even hope of mounting a credible threat to Obama, he will have to deal with a reckoning of how he got the nomination.

Given the enormous advantages in money and organization that he enjoyed in Wisconsin, his victory there was hardly overwhelming. In fact, he won by just five percentage points—forty-three per cent to thirty-eight per cent—a substantially narrower margin than the polls had indicated. Still, a win is a win—especially when the entire G.O.P. establishment is eager to declare the race done and dusted, and many voters agree. Looking at the actual polling returns, the good news for Romney is that, as in Illinois, he did very well in suburban areas, which is where most Republicans (and non-Republicans) live. In my post on Monday, I specifically mentioned three heavily Germanic G.O.P. strongholds near Milwaukee—Waukesha, Washington and Ozaukee counties—which would prove pivotal if Santorum mounted a serious threat. He didn't. Romney carried them all by at least twenty percentage points.

A cynical reading of these figures is that many Wisconsin Republicans voted for the Mittster because they think he's going to be the candidate anyway, so they figure they might as well rally 'round him. The network exit poll showed that fully eighty per cent of voters think Romney will win the nomination. Confirming the old saw that Americans don't like to back a loser, Santorum trailed Romney by more than twenty percentage points among these voters.

An interpretation more favorable to Romney is that, once he doesn't have to worry about wrapping up the nomination, he'll be able to rally suburban Republicans and even some independents in places like Arizona, Florida, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Virginia—states he has to win if he is to become President. His victory speech Tuesday night, in which he talked of "decent people who are running hard to keep in place," of high gas prices, and working moms living in poverty, was intended to show he understands the problems of ordinary Americans—that he can relate to Sam's Club Republicans as well as Neiman Marcus Republicans

But after all the attacks by Santorum, Newt Gingrich, and Rick Perry—in case you've forgotten, the latter labelled poor old Mitt a "vulture capitalist"—the rebranding exercise won't be an easy one. Romney has the worst polling numbers of any Republican candidate in recent history. According to a Washington Post/ABC News poll, just thirty-four per cent of Americans think favorably of him, and fifty per cent view him unfavorably. (At this stage in 1996, Bob Dole, whose campaign didn't exactly soar, had an approval rating of forty-nine per cent and a disapproval rating of thirty-six per cent.)

Those are national figures. In twelve battleground states surveyed by USA Today and Gallup, Romney is arguably in even worse shape. In a head-to-head contest with Obama, he is trailing by nine points—fifty-one per cent to forty-two per cent. Among women, Obama's lead is a whopping eighteen points: fifty-four per cent to thirty-six per cent. (Among women under fifty, Romney is trailing by a stunning two-to-one.)

It's fairly easy to see Romney closing the gender gap, at least to some degree, when women no longer have to listen to Santorum espouse his views on contraception, abortion, and other subjects. But can he close enough of it to be competitive? His wife Ann may provide some help. But here too, he will be dealing with another damaging relic of the primary campaign: his promise to close off funding for Planned Parenthood. During the early 1990s, comments by Pat Robertson and other religious conservatives turned states like New Jersey and California against the Republicans. Nothing George H.W. Bush and Bob Dole said could bring them back.

In short, Romney doesn't have time to celebrate his victory. In addition to trying to finish off Santorum in Pennsylvania later this month, he needs to relaunch his own campaign, while fending off the attacks from the Obama forces, which from here on out will be constant. Absent a blow-up in the economy or a foreign policy disaster, I am skeptical about whether he is up to the task, and not just because of the primary campaign's legacies.

I stick with what I said a couple of weeks ago, following the Etch-a-Sketch gaffe by one his senior advisors, when I labeled Romney "pathetic": he simply isn't very skillful politician, and his campaign isn't sharp enough to make up for his deficiencies. He makes gaffes, his message is muffled, and he isn't much of a communicator. Even last night, on what should have been a moment of triumph, he gave a strangely flat speech. (Congressman Paul Ryan, who introduced him, appeared to get bigger cheers from the crowd.) Of course, anything could happen between now and November, and Obama's disapproval ratings remain high—although not quite as high as Romney's are. On the betting site Intrade earlier today, the implied probability of Romney winning the presidency was 36.3 per cent, roughly one in three. To me, at least, that sounds about right.

Photograph by Scott Olson/Getty Images.

April 2, 2012

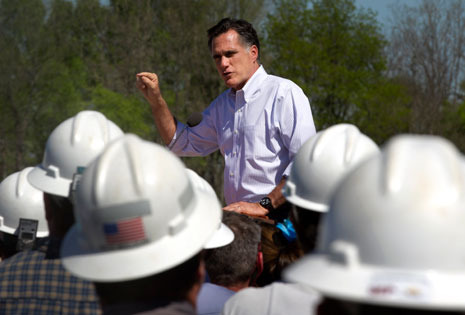

Wisconsin Primary: Can Santo Pull Off a Shocker?

It wouldn't be the first primary race in Wisconsin to spring a surprise. Forty years ago, Hubert Humphrey headed into an Easter-week Democratic primary with a healthy lead in the opinion polls, only for George McGovern to score an upset victory that established him as the front-runner.

"The results were such a jolt to the Conventional Wisdom," Hunter S. Thompson wrote, "that now—with a cold gray dawn bloating out of Lake Michigan and Hubert Humphrey still howling in his sleep despite the sedatives in his room directly above us—there is nobody in Milwaukee this morning, including me, who can even pretend to explain what really went down last night."

If Rick Santorum somehow defies the polls tomorrow night and comes out ahead of Mitt Romney, the Good Doctor might well rise from his grave to record the moment. My, how he would have enjoyed this campaign—at least, before the booze, the drugs and the writer's block sent him nuts with self-loathing. An asset-stripping Mormon gazillionaire versus a Roman Catholic home-schooler who makes Pope Benedict look like a subversive liberal. Still lurking in the background: a puffed-up Georgian squarehead who conducts himself like a latter-day Herodotus and a fiery Texan goblin who wants to abolish the Federal Reserve. Gone but not forgotten: Rick "Oops" Perry, and Herman"9-9-9" Cain.

What fun we've had over the past eight months. Now, though, the killjoys at Republican HQ are intent on unplugging the sound system and telling the revellers that its time to go home. Having deliberately devised this extended primary season as a means of focussing attention on the party, the G.O.P. geniuses have decided it has been rather too successful, and it's time to round upon President Obama. Hence the raft of endorsements Romney has received in recent days, including two timely shout-outs from Wisconsin's best-known Republican politicians: Congressman Paul Ryan and Senator Ron Johnson.

Thankfully, Santorum hasn't got the message. On the eve of the voting, he's still out there in the cities and small towns of Wisconsin, making stops at bowling lanes, building-supply stores, and cheese factories. This afternoon, he is due to speak in Ripon, population 7,680, the unofficial birthplace of the G.O.P. (In 1854, a small group opposed to the pro-slavery Kansas-Nebraska Act met there and took on the name "Republicans.") All in all, Santorum has visited twenty-five of Wisconsin's counties. Romney has visited just five. (He's adding another five today.)

Will history and shoe leather carry Santo to victory? Probably not. A month ago, a survey from the polling firm P.P.P. showed him sixteen points ahead of Romney. In a new poll that P.P.P. released today, Romney is up by seven points: forty-three per cent to thirty-six per cent. Other polls present a similar picture. Of six that were taken over the past week, not a single one showed Santorum ahead. Romney is feeling so confident that over the weekend he publicly predicted a victory.

There's no mystery about what has turned things around for the Mittster. The recent endorsements were helpful, but what really moved the polling numbers was negative campaigning and money. In the past few weeks, Romney and his Super PAC have outspent Santorum by four to one, blanketing the local airwaves with negative ads. Santorum has responded with some shots at Romney's record, including a rather clever spot that compares it to Obama's. But that ad is only going statewide in Wisconsin today—a fact that says pretty much everything about Santorum's campaign, and how ill organized it is compared to the Romney machine.

Still, until I see some actual voting returns from the suburbs around Milwaukee and Green Bay, I wouldn't entirely rule out another Santorum shocker. He's outperformed his poll ratings in other states, and it would be no surprise to see him do it again. But for him to win rather than come close, he needs a last-minute swing in his favor. Actually, in the new P.P.P. survey, there is a hint of one. Among voters who have decided in the past few days, Santorum is leading Romney by fifty-two per cent to twenty-seven per cent. (Unfortunately for Santorum, these people only made up nine per cent of respondents.)

Betting on Romney in a heartland state like Wisconsin is always a risky proposition. Santorum won the neighboring states of Iowa and Minnesota. Again tomorrow, he will have some things going in his favor. About forty per cent of the electorate will be drawn from rural areas, where Romney always does badly. If Santorum can rack up big victories in the sparsely-populated outlying regions, the race will come down to the suburban counties in the southeast of the state—such as Waukesha, Washington and Ozaukee, which are all near Milwaukee.

The voters in these counties are almost all white: about half of them are of German extraction. But as Craig Gilbert, a columnist at the Milwaukee Journal, pointed out yesterday in an insightful piece, they are "less moderate, less affluent, and more socially conservative than the white-collar suburbs Romney won so easily in Illinois two weeks ago." Santorum has been a frequent visitor to this area, and, as evidenced by his mean bowling form, he is a much better cultural fit there than his strike-challenged opponent.

A victory for Romney tomorrow would see a concerted effort on the part of the G.O.P. establishment and the media to proclaim him the nominee-elect. A defeat would extend his torture. With a win in Maryland, where he's heavily favored, he'd probably end the day winning more delegates than Santorum anyway. But Tampa would still seem a long way off.

Photograph by Eric Thayer/The New York Times/Redux.

March 30, 2012

Endorsing Romney: The Said and the Unsaid

With the next round of G.O.P. primaries coming up on Tuesday, and many Republicans eager to draw the entire thing to a close, Mitt Romney has been garnering yet more endorsements. The latest one is from Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan, the right-wing firebrand, who went on the Fox News Channel this morning to call on Republicans to unite behind the front-runner.

Romney's campaign is understandably eager to show off all the people who are supporting him. But the actual endorsements bear inspection. Most of them are respectful. A few are warm and gracious. But many, particularly those from ardent conservatives, appear to have been drawn from the endorser with a pair of dental tweezers. Often, what they don't say is as significant as what they do say. Here, for students of political language, is a quick taxonomy:

The Genuine Article: Ideally, what you want in an endorsement is not just a statement of support but a character reference—an assurance that this is the best person to lead the country and uphold its values. These gracious two sentences from former President George H. W. Bush, whom Romney met with in Houston yesterday, provided a textbook example:

Barbara and I are very proud to fully and enthusiastically endorse and support our old friend, Mitt Romney. He's a good man, he'll make a great President, and we just wish him well.

The Lukewarm: During the Florida primary, Jeb Bush, Old Poppy's eldest son, conspicuously failed to endorse Romney, leading to speculation that he might jump into the race as a savior candidate. After Romney won the Illinois primary, which effectively ruled out the possibility of a late entry, Bush released this one paragraph statement, which contained virtually nothing about Romney as a person:

I am endorsing Mitt Romney for our Party's nomination. We face huge challenges, and we need a leader who understands the economy, recognizes more government regulation is not the answer, believes in entrepreneurial capitalism and works to ensure that all Americans have the opportunity to succeed.

The "Let's Make This About Obama": Another way to endorse the Mittster without really focussing on him is to try to shift the discussion onto defeating the President. That's what Marco Rubio, the Florida Senator whom many regard as a candidate for the number-two spot on a Romney ticket, did on Sean Hannity's show the other night, when he came out in favor of Romney:

The quicker we can get this campaign on that focus—focussed on the President's record, on the alternative that we offer—the better off we're going to be as a movement but also the better off the country's going to be . I am endorsing Mitt Romney and the reason why is not only is he going to be the Republican nominee, but he offers at this point such a stark contrast to the President's record.

Even this was apparently too enthusiastic for Rubio. In an interview with The Daily Caller on Thursday, he said, "There are a lot of other people out there that some of us wish had run for president—but they didn't. I think Mitt Romney would be a fine president, and he'd be way better than the guy who's there right now."

The Stone Cold and Mitt-less: For conservatives who simply can't face the prospect of saying nice things about "the Massachusetts Moderate," one option is not to mention him at all by name. The trick is to say, simply, that it's time for Republicans to bring an end to the circular firing squad. This is what Utah Senator Mike Lee did earlier this week, when he told the Salt Lake Tribune:

This is a pretty critical year. There are big decisions for the country to make and … I think we would be well advised as Republicans to start getting behind our eventual nominee. I think we're now reaching the point where we can see prolonging this process further could undermine our ability to get a Republican candidate elected, and it could also distract from getting our Senate candidates elected.

The Non-Endorsement Endorsement: If you are an eminent conservative, this dodge provides a good way to get across the message that while you are backing Romney's candidacy for utilitarian reasons, you still have some serious reservations about him. Take this weaselly statement from Senator Jim DeMint, of South Carolina, who is one of the leaders of the Tea Party contingent on Capitol Hill:

I can tell conservatives from my perspective is that, I'm not only comfortable with Romney, I'm excited about the possibility of him possibly being our nominee. Again, this is not a formal endorsement and I do not intend to do that right now but I just think we just need to look at where we are.

The James Carville Special: Here's the message: It's the economy, stupid. And Mitt, for all his failings, knows a lot more about that subject than Santo or Newt. So let's suck it up and get behind him. Of course, you don't have to spell it all out that explicitly. Instead, you can follow the example of Eric Cantor, the House Majority Leader and say something like this:

What I have seen is a very hard-fought primary. And we have seen now that the central issue about the campaign now is the economy. I just think there's one candidate in the case who can do that, and it's Mitt Romney.

Actions Speak Louder than Words: If you are a big enough celebrity, you don't have to say anything. Simply appearing on the same stage as Romney is enough. That's what Kid Rock did during the Michigan primary, and everybody got the message.

The "Mitt's Not Such a Bad Guy": We all know Romney has a problem relating to people, or they have a problem relating to him. Either way, anybody who can speak to this issue in a reassuring way is doing the candidate a big favor. Here's the riff his campaign would like to get out: "O.K., he looks and talks like a rich doofus. But when you get to know him, he's just a regular guy that you'd like to have a beer with, or a soda pop anyway." This tweet from rock guitarist and gun enthusiast Ted Nugent, who had previously supported Rick Perry, was on-message:

The Successful Businessman: If all else fails, remind people that Romney might have started out rich but he also made a boatload of money on his own account. In Republican circles, this will be taken to mean he can't be all bad. Gene Simmons, another rocker for Romney, hit the sweet spot with this glowing tribute:

Mitt Romney's got a chance and he's got the experience. He's run successful companies, knows how to make money….

The Great Olympian: Many people have forgotten that Romney helped rescue the 2002 Winter Games in Salt Lake City. To be sure, he may have exaggerated his role a bit, but reminding people of what he did is a good way to express support for him while staying out of party politics. Here's a representative quote from Sharlene Wells Hawkes, a former Miss America:

Mitt Romney gave Utah world-class leadership. He turned around our Olympics.

The Trump Two-Step: Some conservative Republicans face the problem that, earlier in the race, they expressed support for other candidates. No problem. Just follow Donald Trump's example (before Christmas he appeared with Newt Gingrich) and lay it on thick—the thicker the better:

It's my honor to endorse Mitt Romney. He's tough, he's smart, he's sharp. He's not going to allow bad things to continue to happen to this country that we all love. So, Governor Romney, go out and get 'em. You can do it.

Photograph by Tom Pennington/Getty Images.

March 29, 2012

After the Court Ruling: Obamacare and the Campaign

Now that the three days of Supreme Court hearings about Obamacare are over, let's get down to the issue consuming political junkies: how will the Court's decision, which is expected to be handed down sometime in June, affect the Presidential race?

The conventional wisdom is that, whatever happens, the G.O.P. stands to benefit. If the Justices throw out the individual mandate or strike down the entire law, it will be a humiliating setback for the President. If the Court upholds the law's constitutionality, the Republicans will have a rallying cry for the fall: repeal Obamacare. I am not so sure about this logic. A decision to strike down the reforms could easily rebound in the President's favor, neutralizing an unpopular issue and helping him rally his base. If the Justices rule in favor of the Administration, health-care reform will still be a big debating point come this fall. But with the author of Massachusetts Mittcare at the top of the Republican ticket, aggressively pushing for the repeal of Obamacare wouldn't be without dangers for the G.O.P.

The Affordable Care Act is currently unpopular, and, on the face of things, anything that reminds voters of its existence is bad news for the White House. Politico's Alexander Burns reported this morning: "Republican strategists and party officials have begun crafting a strategy that puts health care front-and-center in the campaign against President Barack Obama, even if Mitt Romney is at the top of their ticket." The G.O.P.'s determination to seize on Obamacare is hardly surprising. A New York Times/CBS News poll released earlier this week showed that the majority of Americans (fifty-four per cent) disapprove of the health-care act, and more than two in three of them (sixty-seven per cent) think that the Supreme Court should throw out all or part of it. And this is despite the fact that some of the law's individual provisions, such as forcing insurance companies to cover people with preëxisting conditions and enabling young adults to remain on their parents' insurance plans, are highly popular.

The detailed findings of the Times/CBS News poll explain why Obama and his campaign team rarely bring up health-care reform, preferring to focus on the auto bailout and other measures that are more popular. Just nineteen per cent of respondents said they thought the 2010 law would help them personally; thirty-one per cent said it would hurt them; and forty-three per cent said it wouldn't have any impact. The answers to another question showed even more skepticism. More than half of the respondents (fifty-two per cent) said they believed the law would eventually raise their own health-care costs, and fewer than one in six (fifteen per cent) said they believed it would lower their costs.

To some extent, these findings reflect general skepticism about government programs. But the timeline of the health-care reform also plays into them. Ever since the law was passed, right-wing politicians and commentators have been barraging the public with warnings of a government takeover, death panels, socialism, and all the rest—this for a private-sector plan originally put forward by the Heritage Foundation! The tangible benefits that the reform will deliver, in terms of more affordable coverage for those outside group plans, cheaper prescription drugs, and fewer people uninsured, will only be felt gradually.

In pushing ahead with this plan, Obama was taking a political risk that his campaign strategists may now be regretting. It would hardly be surprising if some of them are quietly rooting for the Court to strike down the entire Affordable Care Act, which would shift the debate from whether it's legal to what to do without it. Obama could immediately mount a legislative campaign to rescue the reform's popular bits, such as barring insurers from turning away sick people, and seek to make the Republicans vote on his proposals in the fall. With attention once again focussed on the evils of the private-insurance system, rather than on Obama's efforts to remedy them, the political calculus would shift back in his favor—or, it might.

If the Supreme Court were held in higher esteem, the very sight of it issuing a historic rebuke to the President's signature initiative could inflict great damage on his reputation. These days, though, the Court is packed with political appointees from both parties, and the public views it accordingly. The primary effect of a five-four ruling by the conservative Justices would be to rile up Democratic activists and impart some much needed energy to Obama's campaign effort. Like Roosevelt in his 1936 reëlection bid, he would be able to campaign against a reactionary Court that had overstepped its bounds. On the Republican side, things would be reversed. By giving the Tea Party wing of the G.O.P. what it has been demanding since 2010—the repeal of Obamacare—the Court would probably rob it of some of its fervor.

If the Court upholds the legality of the health-care reform, the impact would be less dramatic and more favorable to the G.O.P. From dawn to dusk, it will be able to rail against Obamacare. But the party will still have to square its demand for a repeal of the reform with the fact that it was explicitly modelled on the handiwork of its own candidate. This, of course, is the argument that Rick Santorum has been pushing for months: in nominating Romney, the party would rob itself of its biggest issue.

Today's Politico story indicated that G.O.P. strategists are busy tussling with this dilemma. Brian Walsh, the president of the American Action Network, suggested that the party could focus on aspects of Obama's reform that aren't closely tied to the Massachusetts model, such as setting up an independent panel of experts to control costs—the "death panel"— and the cuts to Medicare that the administration has proposed to help pay for the subsidies of low-income workers who buy insurance. "I would say that health care continues to be an extremely dominant issue that can be used by Republicans in the fall," Walsh insisted. Paul Lindsay, communications director for the National Republican Congressional Committee, agreed. He said public opposition to Obamacare has "less to do with the individual mandate than it does about the bureaucracy and regulations that Obamacare created…Voters are viewing this through the 1099 requirements, they're viewing it through Medicare cuts, they're viewing it through the employer dropping them or their doctor not being able to treat them anymore."

There may be something to these arguments. But Romney is the person who is going to have to put them to the American public, and, however the G.O.P. tries to spin it, that remains a big problem. After all, this is someone who, during the 2008 campaign, made this statement:

Mandates, I love mandates, mandates work, this is what we need to do, we need to force people to buy insurance.

If and when Romney comes to debate Obama, he will doubtless try to explain that he was talking about mandates at the state level, rather than mandates at the federal level, which he never supported—a distinction that may well go over the head of many voters. Obama, meanwhile, will be relishing telling the tale of how, after he arrived in the White House, Nancy-Ann DeParle, his senior health-care advisor, persuaded him to base pretty much his entire reform plan on what Romney had done in Massachusetts.

A highly skillful politician could perhaps make the argument that Obamacare is totally different from Mittcare. And that's another reason why I think that Obamacare, even if it survives the challenge in the Supreme Court, won't be the pivotal factor in this year's Presidential campaign. Nothing we have seen from Romney suggests he is up to such a task.

March 28, 2012

Justice Kennedy and the Search for a "Limiting Principle"

Thanks to everybody who commented on my previous post—wherein I described the Obamacare Supreme Court case as a "bad joke"—even those who sought to unmask me as an agent of the British monarchy who knows nothing about the American traditions of individual liberty and popular sovereignty. Today, just for the sake of argument, I'll assume that the stated concerns of the conservative Justices aren't merely a cover for furthering a thirty-year-old right-wing project to roll back the New Deal and the Great Society.

After Tuesday's hearings, Lyle Denniston, a reporter at the excellent SCOTUSblog, summarized things thus: "If Justice Anthony M. Kennedy can locate a limiting principle in the federal government's defense of the new individual health insurance mandate, or can think of one on his own, the mandate may well survive. If he does, he may take Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., and a majority along with him. But if he does not, the mandate is gone."

Time after time during Tuesday's hearing, Justice Kennedy and his conservative colleagues pressed Donald Verrilli, the solicitor general, on where the federal government's power to oblige people to purchase products in the marketplace would end. Justice Scalia, trotting out an argument first raised in the D.C. Circuit by Judge Laurence Silberman, asked whether the feds could mandate purchases of broccoli. Chief Justice Roberts asked about cell phones. Perhaps the key exchange came when Justice Alito said to Verrilli, "Before you move on, could you express your limiting principle as succinctly as you possibly can?"

A number of commentators have criticized Verrilli for failing to provide a pithy answer. But what he said was perfectly comprehensible. Rather than attempting to establish a broad legal right on the part of the federal government to force people to buy things if it is in the public interest, he restricted his argument purely to the health-insurance market. Citing the Necessary and Proper Clause of the Constitution, Verrilli said that as part of a "comprehensive scheme" to reform health care, the government could regulate behavior that might well undermine these efforts, such as the failure to purchase health insurance. Secondly, under the Commerce Clause, which I referred to yesterday, the federal government could regulate the "timing of payments by imposing an insurance requirement when you will get the care in that market, whether you can afford to pay for it or not and shift costs to other market participants."

Now, there aren't many commodities sold in a market that people will receive whether they pay for them or not, thus creating the potential for shifting costs onto other people. Broccoli isn't such a commodity, and neither is a cell phone. Some of the liberal Justices pressed Verrilli to go broader. Justice Breyer, citing the 1819 McCulloch v. Maryland case, in which the Court approved the founding of the Second Bank of the United States, suggested that the federal government had the right to create commerce where none previously existed—a bone of contention to Kennedy and others—and that this principle could be used to make people buy other things, such as burials. But Verrilli stood his ground, saying he was making a narrower case restricted to health insurance.

For fans of high principles and impassioned debates, this wasn't very satisfying. I, for one, would have enjoyed seeing Verrilli challenging some of the conservative Justices on their own grounds, and defending the individual mandate on the grounds of economic efficiency and cost-benefit analysis. Ever since the rise of the "law and economics" movement, conservatives like Roberts have elevated efficiency concerns to a potentially decisive role. And it's patently clear that if you want to make retain a private insurance market and make it work efficiently, providing affordable coverage to more people, you need some form of individual mandate.

But given the makeup of the court, I think Verrilli made the right choice. If they had been forced to acknowledge the existence of a hitherto unnoticed general principle that justifies an extension of government interventions in the marketplace, the five conservative Justices would certainly have balked. In restricting his argument exclusively to health insurance, the solicitor general provided Justice Kennedy, in particular, with a potential out—a way to approve the individual mandate as a one-off that doesn't apply to other commodities. Kennedy, in his final words, appeared to be moving in this direction. Young people and others who don't buy health insurance come "very close to affecting the rates of insurance and the costs of providing medical care in a way that is not true in other industries," he said. Come June, when the case is finally decided, this just might turn out to be the limiting principle that saved Obamacare.

Photograph by Karen Bleier/AFP/Getty Images.

March 27, 2012

Obamacare Supreme Court Case Is a Bad Joke

Forgive me if a wry tone eludes me when it comes to today's proceedings in the Supreme Court. As far as I am concerned the whole thing is absurd—yet another example of how America's antiquated system of government, and its determined refusal to accept the economic realities of the modern world, is undermining its future.

Early on in this morning's session, Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote on the court, said that the U.S. government had a "very heavy burden of justification" to show that an individual mandate to purchase health-care insurance was constitutional. Really? Only if Kennedy and his Republican-appointed colleagues are willing to throw out economic logic as well as seventy years of legal precedent, which, judging by their harsh questioning of Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, Jr., they may well be.

The economics isn't very complicated. The health-care industry, which makes up about a sixth of the economy, is rife with inefficiency, waste, and coverage gaps. In seeking to remedy some of these problems, the Obama Administration made a deal with the private-insurance industry—the same deal Mitt Romney made when he was governor of Massachusetts. On the one hand, the federal government barred the insurers from discriminating against the sick and the elderly, thereby raising the industry's costs. On the other hand, the feds obliged uninsured individuals to purchase coverage, thereby expanding the insurers' revenues. We can argue whether this was the best way to proceed. (At the time the bill was passed, I raised some doubts about how much it would cost.) But it was a straightforward instance of the central government seeking to redress the failures of the private market—something akin to imposing fuel standards on auto manufacturers, providing state pensions, and forcing banks to hold adequate capital reserves.

In a modern, interconnected economy, activist government policies to remedy market failures are essential. Rather than confronting this argument head-on, which would involve publicly defending the actions of the banks, the insurers, and the industrial polluters, the right has settled on a strategy of trying to undermine the government through the courts, where its pro-corporate agenda can be repackaged as a defense of ancient freedoms.

Thus the bogus constitutional challenge to Obamacare, and, in particular, the individual mandate. As my colleague Jeffrey Toobin pointed out in an excellent post this morning, the issue resolves around the Commerce Clause of the Constitution, which gives the federal government the power to "regulate Commerce

among the several States." Where does this power begin and end? In the famous 1942 case of Wickard v. Filburn, the Court said that the federal government's authority extends to any activity that "exerts a substantial economic effect" on commerce crossing state lines.

The case involved Roscoe Filburn, an Ohio farmer who wanted to grow more wheat than he had been allotted under quotas introduced during the Great Depression to drive up prices. In deciding against Filburn and in favor of the Department of Agriculture, the justices pointed out that the actions of individual wheat farmers, taken together, affect the price of wheat across many states. That is what gives the federal government the power to limit their actions.

Under the Wickard v. Filburn standard, the individual mandate is clearly constitutional. If ever there was an industry that crosses state lines, it is health care. As the Solicitor General's office noted in its brief to the Court on the merits of the case, health-care spending "accounts for 17.6 percent of the nation's economy." From a legal perspective, that is where the matter should rest.

But, of course, this case isn't ultimately about the law—it is about politics. The four ultra-conservative justices on the court—Alito, Roberts, Scalia, and Thomas—are in the vanguard of a movement to roll back the federal government and undermine its authority to tackle market failures. The movement began in the nineteen-eighties, when the Federalist Society got its start and Ronald Reagan appointed one of its members, Scalia, to the court—and for thirty years it has been gathering strength.

Thus the creation of a new legal theory to sink Obamacare: the idea that while the federal government might well have the authority to regulate economic activity, it doesn't have the right to regulate inactivity—such as sitting around and refusing to buy health insurance. Now, it is as plain as the spectacles on Antonin Scalia's nose that opting out of the health-care market is about as realistic as opting out of dying. But necessity is the mother of invention. And, judging by his questions this morning, it is this invention that Kennedy has fastened on.

As I said at the beginning, it's a bad joke—upon us all.

Illustration by Dana Verkouteren/AP Photo.

Obamacare Supreme Court Case is a Bad Joke

Forgive me if a wry tone eludes me when it comes to today's proceedings in the Supreme Court. As far as I am concerned the whole thing is absurd—yet another example of how America's antiquated system of government, and its determined refusal to accept the economic realities of the modern world, is undermining its future.

Early on in this morning's session, Justice Anthony Kennedy, the swing vote on the court, said that the U. S. government had a "very heavy burden of justification" to show that an individual mandate to purchase health-care insurance was constitutional. Really? Only if Kennedy and his Republican-appointed colleagues are willing to throw out economic logic as well as seventy years of legal precedent, which, judging by their harsh questioning of Solicitor General Donald Verrilli, Jr., they may well be.

The economics isn't very complicated. The health-care industry, which makes up about a sixth of the economy, is rife with inefficiency, waste, and coverage gaps. In seeking to remedy some of these problems, the Obama Administration made a deal with the private-insurance industry—the same deal Mitt Romney made when he was governor of Massachusetts. On the one hand, the federal government barred the insurers from discriminating against the sick and the elderly, thereby raising the industry's costs. On the other hand, the feds obliged uninsured individuals to purchase coverage, thereby expanding the insurers' revenues. We can argue whether this was the best way to proceed. (At the time the bill was passed, I raised some doubts about how much it would cost.) But it was a straightforward instance of the central government seeking to redress the failures of the private market—something akin to imposing fuel standards on auto manufacturers, providing state pensions, and forcing banks to hold adequate capital reserves.

In a modern, interconnected economy, activist government policies to remedy market failures are essential. Rather than confronting this argument head-on, which would involve publicly defending the actions of the banks, the insurers, and the industrial polluters, the right has settled on a strategy of trying to undermine the government through the courts, where its pro-corporate agenda can be repackaged as a defense of ancient freedoms.

Thus the bogus constitutional challenge to Obamacare, and, in particular, the individual mandate. As my colleague Jeffrey Toobin pointed out in an excellent post this morning, the issue resolves around the Commerce Clause of the Constitution, which gives the federal government the power to "regulate Commerce

among the several States." Where does this power begin and end? In the famous 1942 case of Wickard v. Filburn, the Court said that the federal government's authority extends to any activity that "exerts a substantial economic effect" on commerce crossing state lines.

The case involved Roscoe Filburn, an Ohio farmer who wanted to grow more wheat than he had been allotted under quotas introduced during the Great Depression to drive up prices. In deciding against Filburn and in favor of the Department of Agriculture, the justices pointed out that the actions of individual wheat farmers, taken together, affect the price of wheat across many states. That is what gives the federal government the power to limit their actions.

Under the Wickard v. Filburn standard, the individual mandate is clearly constitutional. If ever there was an industry that crosses state lines, it is health care. As the Solicitor General's office noted in its brief to the Court on the merits of the case, health-care spending "accounts for 17.6 percent of the nation's economy." From a legal perspective, that is where the matter should rest.

But, of course, this case isn't ultimately about the law—it is about politics. The four ultra-conservative justices on the court—Alito, Roberts, Scalia, and Thomas—are in the vanguard of a movement to roll back the federal government and undermine its authority to tackle market failures. The movement began in the nineteen-eighties, when the Federalist Society got its start and Ronald Reagan appointed one of its members, Scalia, to the court—and for thirty years it has been gathering strength.

Thus the creation of a new legal theory to sink Obamacare: the idea that while the federal government might well have the authority to regulate economic activity, it doesn't have the right to regulate inactivity—such as sitting around and refusing to buy health insurance. Now, it is as plain as the spectacles on Antonin Scalia's nose that opting out of the health-care market is about as realistic as opting out of dying. But necessity is the mother of invention. And, judging by his questions this morning, it is this invention that Kennedy has fastened on.

As I said at the beginning, it's a bad joke—upon us all.

Illustration by Dana Verkouteren/AP Photo.

March 25, 2012

From Etch A Mitt to Louisiana: Romney's the "Pathetic" One

Well, I'm about ready to give up on my old pal Mitt.

Over the last few weeks, I've been trying to give him a boost: offering him unsolicited advice on how to revive his campaign, criticizing the Obama campaign for misrepresenting the auto bailout, and praising his victory speech in Illinois. To be sure, my motives weren't the purest: having signed on to cover the campaign, I'd prefer a competitive race. But still: I did my best.

After the last week, though, I've come to the conclusion that trying to rescue Romney's Presidential bid may be a hopeless task. Really, what prospect is there for a campaign that, on the day it should have been celebrating a big win in Illinois, suggests that its man's political positions have all the permanence of a child's drawing on an Etch A Sketch? A campaign which now, after getting its derriere handed to it in Louisiana, has the temerity to issue a statement calling its opponent, Rick Santorum, "pathetic"? There isn't much hope: that's my answer. The Romney campaign consists of a weak candidate and a back-room staff that would have difficulty contesting a city-council election. As of now, about the only thing it has going for it is money—an advantage that Obama's war chest will vitiate in the general election.

The Etch A Sketch gaffe, it is now clear, was far more than a one-day story. Conceivably, it was the defining moment of the G.O.P. primaries. From now until November, it will dog Romney every step he takes. Republican voters "want to see someone who they can trust," Rick Santorum said Sunday morning on CBS's "Face the Nation," "someone who's not running an Etch A Sketch campaign, but one that, you know, has their principles written on their heart, not on an erasable tablet." Meanwhile, over on NBC's "Meet the Press," David Plouffe, President Obama's senior political adviser, was busy clubbing Romney over the head with the stick he had been handed. The right-wing positions Mitt had taken during the campaign were "etched in stone" and were "not going to be erased," Plouffe said repeatedly.

It's one thing for the candidate himself to make occasional gaffes—in a long and exhausting race, that's to be expected. But for a Presidential campaign's designated mouthpiece to fire off a howler of this magnitude is unforgivable. What was Eric Fehrnstrom, one of Romney's senior advisers, thinking when he went on CNN's "Starting Point" show last Wednesday morning? It wasn't as if he was backed into a corner and panicked. The questioner, John Fugelsang, simply brought up an obvious query: Wasn't Romney concerned that some of the positions he has taken in the primaries might alienate moderate voters in the general election? Rather than deflecting the question, Fehrnstrom said: "Well, I think you hit a reset button for the fall campaign. Everything changes. It's almost like an Etch A Sketch. You can kind of shake it up and restart all over again."

No you can't—not when it comes to this sort of blunder. In four short sentences, Fehrnstrom confirmed what many Americans had suspected all along about Romney: he's a shameless panderer, willing to take on and cast off political positions like so many pairs of socks. Even if the Mittster confines Fehrnstrom to a padded room until November, which would be advisable, the damage has been done. Come the fall, his face and words will be appearing in living rooms across the nation—on ads produced by the Obama campaign.

Now comes yet another drubbing for Romney in the South—this time in Louisiana. If you are a Republican candidate and you get trounced by twenty-two points in the heartland of the G.O.P., the prudent thing to do is congratulate your opponent, point out that it wasn't a state you expected to win, and get the heck out of there. Romney did that much; when last night's result came in, he was busy raising money in California. But the bozos on his campaign couldn't resist taking some potshots at Santorum, thereby keeping the story going. Their statement compared Santorum's perfectly understandable elation about the Louisiana result to "a football team celebrating a field goal when they are losing by seven touchdowns with less than a minute left in the game." Fair enough. The G.O.P. primary is actually still in the third quarter, but with Romney still leading by about three hundred delegates, it is hard to see his principal opponent coming back. Rather than leaving it there, though, the Romney campaign added some more derogatory comments:

His attempts to distract from his listless campaign and the conservative backlash caused by his suggestion that keeping President Obama would be better than electing a Republican are becoming sadder and more pathetic by the day.

Sadder and more pathetic? Really? When CBS's Norah O'Donnell, who was hosting "Face the Nation," read out the Romney statement to Santorum, who has now won eleven states, many of them by large margins, he could only smile. "That's a desperate campaign that has no message," he said. Actually, that's not strictly true. As I pointed out on Wednesday morning, Romney's victory speech in Illinois did contain the germ of an anti-Obama platform. But his campaign's pratfalls in the past few days have overshadowed his words and left him looking like an overmatched amateur.

Assuming Romney eventually secures the nomination, which he most probably will, he will be going up against an improving economy; an incumbent President with great rhetorical skills, evident in his tone-perfect reaction to the Trayvon Martin shooting; and an Obama campaign operation that, on recent evidence, is far superior to his own. And what does he have on his side? High gas prices, memories of a lengthy economic slump, and the Iranian machinations of Benjamin Netanyahu.

As of now, it doesn't look like a fair fight. One of these days, I might have to give up on Mitt completely, join the rest of the media in piling on against him, and look for a more exiting sport to cover. Golf, perhaps. With a scarred Tiger Woods making a comeback and Northern Ireland's Rory McIlroy occupying his former spot as the young gun, it has some real narrative possibilities.

Photograph: Steven Senne/AP

Santo Romps in LA; Same Old Woes for Mitt

When I said the other day that by the end of the week Mitt Romney would be once again mired in the bayou, I didn't realize he'd sink this far in. At 1:00 this morning, with all of the votes in the Louisiana primary having been counted, Rick Santorum had emerged victorious by a whopping twenty-two points. He got forty-nine per cent of the vote, the Mittster got twenty-seven per cent, and Newt Gingrich got sixteen per cent.

Following Santorum's failure to mount a real challenge to Romney in Illinois, the punditocracy, myself included, virtually wrote off his candidacy. But somebody forgot to tell the Republicans of Louisiana—something Santorum remarked upon from Green Bay, Wisconsin, after he had been declared the winner. "You didn't believe what the pundits have said, that this race was over," he told a group of cheering supporters. "You didn't get the memo."

To be sure, Santorum was expecting to record a win yesterday—making it eleven states he has added to his column—but not necessarily on this scale. He carried sixty-two of the sixty-three parishes in Louisiana, many of them by huge majorities. Romney's sole victory came in Orleans parish, in New Orleans. The only other places he was even remotely competitive were Jefferson parish, which includes much of the suburbs of New Orleans, and West Feliciana parish, in Baton Rouge. Even there, Santorum defeated him by at almost ten points.

Once again, Romney failed to get thirty per cent of vote in a southern state. And once again, one of the big factors working against him was religion. In the network exit poll, more than half of the respondents identified themselves as evangelicals, and in this group Santorum led Romney by close to three to one. (Fifty-six per cent to twenty per cent.) But it wasn't just a matter of born-again Christians refusing to pull the lever for a Mormon. Many other people refused to vote for Romney, too.

According to the exit poll, he lost the men's vote, the women's vote, all age groups, all education levels (including the twenty per cent of the voters who had done postgraduate work) and all income groups except those earning more than two hundred thousand dollars a year. For a front-runner, even in a state where the odds were stacked against him, this was hardly a reassuring performance.

What effect will it have on the overall contest? With his eye on the next round of voting on April 3, which features primaries in Maryland, Wisconsin, and the District of Columbia, Santorum said last night: "The race is far from over. Wisconsin, I say to you, let's get it on." That may be wishful thinking, but the fact that Newt Gingrich did so badly will offer Santorum additional encouragement. Even if Gingrich doesn't formally drop out of the race, he is steadily becoming less of a factor.

Doubtless, some of Romney's mouth pieces will be on the Sunday morning talk shows arguing that their man's latest setback, in a state where just twenty delegates were at stake, hardly matters at all. After watching what they have to say and mulling things over, I'll weigh in again and tell you what I reckon.

Photograph: Jessica Kourkounis/Getty

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers