John Cassidy's Blog, page 95

June 18, 2012

After the Greek Election: More Hard Slog Ahead

If the folks in the White House, or anywhere else, were hoping that Sunday’s election result in Greece would mark a turning point in the European economic crisis, they have already been disappointed. When the financial markets opened this morning, traders shrugged their shoulders at the news that pro-bailout parties had scored a narrow victory, and some stock markets, the U.S. one included, fell slightly.

This being a debt crisis, the market that matters most is the bond market. There the reaction was similarly adverse. Prices of Spanish and Italian government bonds slipped once again. Despite last week’s European agreement to bail out Spain’s banks, the yields on Spanish government debt (which move in the opposite direction to the price) reached 7.14 per cent: a record in the euro era. At yields like these, the governments in Rome and Madrid will face great difficulty in financing themselves. Evidently, there is a long way to go before confidence is restored.

To anybody who has been following this long-running saga, that shouldn’t be too surprising. The first rule of European politics is that nothing changes quickly. The second rule is that what happens to small and peripheral countries, such as Greece and Ireland, is largely a sideshow. What really counts is the fate of Italy and Spain, the two big southern economies.

As far as the euro zone as a whole goes, the potential costs and benefits attached to yesterday’s election were always asymmetric. If it went badly—i.e., if the insurgent Alexis Tsipras and his followers in Syriza party emerged as the largest party for a second time—the consequences could have been catastrophic: a collapse of the Greek banking system, contagion throughout Europe, and another big shock to the world economy. If it went well—i.e., if one of the traditional parties came out ahead of Syriza—the best that could be hoped for was that it would buy Europe a bit more time to introduce structural reforms and figure out how to get the continent growing again.

That is what has happened. As far as Greece itself goes, not much has changed. Antonis Samaras, the head of the center-right New Democracy party, which emerged as the biggest group in the parliament, today set to work on constructing a new coalition government. But even if Samaras succeeds, which seems likely, few believe he will have the power or the political will to push through the fresh austerity measures that the previous government agreed to as the price of another bailout. If Greece reneges on its commitments, Germany and France will almost certainly insist on it giving up the euro, at least temporarily. Analysts at Citigroup today estimated the probability of Greece eventually leaving the currency zone at between fifty per cent and seventy-five per cent.

The rest of Europe could withstand an orderly Grexit: many politicians in Brussels and Berlin think they would be better off without the Greeks. But the euro zone couldn’t withstand a wholesale economic collapse in Spain and Italy, which is where attention is now focussed. In the next couple of weeks, policymakers have to make progress on two fronts.

In Brussels, Angela Merkel and François Hollande, the new French President, whose Socialist Party yesterday won a majority in the National Assembly, will have to erect, at least in prototype, some sort of Europe-wide financial safety net—otherwise, a run on the banks in the Mediterranean region is a real possibility. In Frankfurt, Mario Draghi, the urbane Italian who heads the European Central Bank, will have to persuade his colleagues to turn back on the monetary spigots. It was only action by the E.C.B. that calmed the markets at the start of the year, and it’s going to be necessary again.

Neither of these measures would solve the debt crisis. That requires a proper fiscal union, more write-offs for heavily indebted countries, and a proper growth strategy involving monetary and fiscal stimulus. But banking reform and more action from the E.C.B. would keep things going for another while. Sticking doggedly (stupidly?) to my position as a euro-optimist, I am guessing that the policymakers will do what is necessary.

Analysts on this side of the Atlantic often underestimate the commitment to the euro project that still exists throughout Europe, at least on the part of the élites. When, at the very last moment, it comes down to a choice of doing something unpalatable or seeing the currency union destroyed, even German politicians choose the first option. Ordinary people are less enthusiastic about the euro. But the fact remains that, in the past few weeks, voters in Greece and Ireland—two countries that have seen their economies decimated—have narrowly voted to stick with the currency zone. (The vote in Ireland was a referendum on the E.U.’s new stability pact.)

So, no, I still don’t see the euro zone breaking apart. But I don’t see a rapid resolution either. The Europeans are in for more hard slog. And so, to the extent that what happens across the Atlantic affects the U.S. economy, is the Obama Administration.

Photograph by Oli Scarff/Getty.

Random-Winner Theory Triumphs at U.S. Open

And then there were seventeen.

When Graeme McDowell missed a tricky downhill putt on the eighteenth hole at Olympic Club on Sunday night, the world of golf had its seventeenth winner in eighteen major championships going back to the start of 2008. Early last week, I expostulated the theory that nowadays virtually anybody can win a major, and the outcome is essentially random. Well, with Webb Simpson’s U.S. Open victory, the random theory has another data point in its favor.

Not that Simpson is a bad player: he isn’t. Despite being overlooked in many pre-tournament handicapping sheets, mine included, he’s very, very good. Last year, he won twice on the regular tour. And this weekend, after shooting two rounds of sixty-eight on a very difficult golf course that wreaked havoc on the scorecards of many better-known players, he deserved his victory.

But that’s the point of the random-golf theory. These days there are so many good players that picking a winner is like entering the lottery. Simpson was the fourteenth ranked player in the world when his name came up in the year’s second major, but according to the theory it could just have well as been the twenty-eighth ranked player, Ian Poulter, or the forty-second ranked player, David Toms, or, indeed, the one hundred and seventh ranked player, Michael Thompson, who finished tied for second with McDowell, a shot behind Simpson.

As I said last week, the statistical evidence suggests that the outcomes of major championships aren’t totally random. World rankings count for something—as evidenced by Simpson’s high position on the list—but not for very much. Even after two or three rounds of a major, it is often very difficult (if not impossible) to predict what is going to happen. On Friday night, when Tiger Woods was tied at the top with Jim Furyk, most of the television pundits were saying he would win. On Saturday night, after Tiger had shot a four-over-par seventy-five in the third round, most of the same pundits picked Furyk or McDowell, the leaders by two shots, as the victors, with Lee Westwood, who was three shots back, as the main danger man.

Simpson, who was four shots off the lead, was hardly mentioned. At William Hill, the British bookmaker, he was thirty-three-to-one yesterday morning. Seeing those odds, I thought he might well be worth a bet. An even-tempered straight hitter who putts well, he’s the sort of player who often fares well at the U.S. Open. But instead of sticking with Simpson, I allowed sentiment to overcome reason and advised my brother in England to place ten pounds on Ernie Els, for years my favorite player, who was just three shots off the lead.

Once play began, Ernie ran into trouble, as did many of the favorites. Westwood got his ball stuck up a tree on the fifth hole, costing him a double-bogey; McDowell drove it crooked for much of the day; and Furyk, still tied for the lead on the par-five sixteenth hole, hit a beginner’s duck hook into the woods. That’s golf: bad things happen to everybody, the best players in the world included. Sometimes, a player at the very top of his form makes it look easy—Louis Oosthuizen at the 2010 British Open; Rory McIlroy at last year’s U.S. Open—only to fade into the pack when asked to repeat the trick. The result is a different winner at every championship for more than three years, lower television ratings, and lot of frustrated network executives.

Tiger Woods, alone, used to be able to impose order on this chaos. Now, he is reduced to sporting mortality. On Saturday, he struggled with the distance of his irons and kept leaving putts short. On Sunday, starting five shots behind Furyk and McDowell, he went bogey, bogey, double-bogey, par, bogey, bogey at which point NBC couldn’t justify showing him any more. Although much has been made of Woods’s swing changes, the evidence suggests that what is now preventing him from winning another major is the gray matter between his ears. When it no longer counted yesterday, he played great golf, covering the last eleven holes in three under par.

Even Tiger, it seems, is no longer immune from the effects of playing under pressure. Of course, that puts him in with 99.999 per cent of people who have ever played golf competitively. And it means that, when it comes to picking the winners of the last two majors of the year—the British Open and the P.G.A. Championship—I will be relying on a roulette wheel and a Ouija board.

Photograph of Webb Simpson by Stuart Franklin/Getty Images.

June 17, 2012

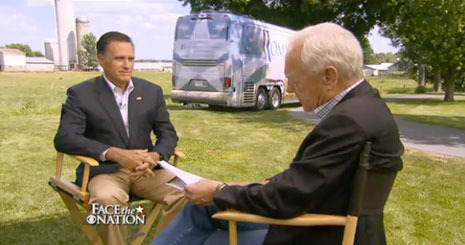

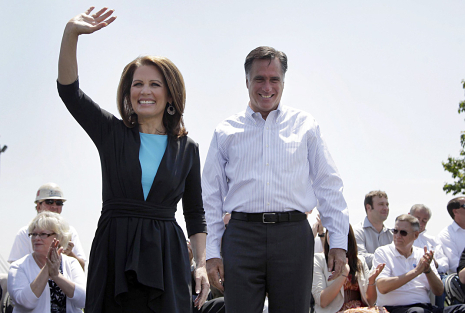

Of Cows and Men: Romney Faces the Nation

Here’s a tip for aspiring politicians: if you’ve agreed to appear on a big national show, and you know there are going to be some awkward questions, arrange to do the interview on a pretty farm with some cows mooching around in the background. That was the tactic Team Romney adopted for their man’s much-anticipated sit-down on CBS’s “Face the Nation,” and it worked out well.

The interview took place in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, one of the stops on the Mittster’s five-day bus tour of six battleground states. While he hemmed and hawed on whether he’d repeal President Obama’s decision to let the children of illegal aliens stay in the country, I am sure that many other viewers, like me, couldn’t keep their eyes off the black and white bovines walking to and fro behind his shoulders. If Romney didn’t exactly dazzle, he came out of the interview pretty much unscathed, which his campaign will consider a victory, and he also managed to get off some highly questionable attacks on Obama without being called on them.

Hitherto, Romney had largely restricted his television appearances to the friendly environs of Fox News. The announcement that he had agreed to an interview with CBS News, the home to attack dogs like Ed Murrow and Dan Rather, raised memories of Rather confronting George H. W. Bush at Black Rock during the 1988 campaign—a set-to that moved old Poppy to comment “It was tension city out there.” This was tranquil Norman Rockwell countryside. Romney and dear old Bob Schieffer, both clad in blue blazers and open-necked oxford shirts, looked like a couple of Wall Street swells attending a Father’s Day brunch at one of their pals’ places in the country. About the only source of tension was whether one of the beasts would stop and drop a cow pie next to Mitt’s right ear. (It didn’t happen.)

Just as he did on Friday, Romney refused to say straight out whether he would strike from the books President Obama’s executive order, which ruled out the possibility of deportation for roughly eight hundred thousand undocumented young aliens. The first time Schieffer asked him, he said, “Let’s step back and look at the issue….” The second time, he said, “It would be overtaken by events.” And the third time, he said, “We’ll look at that setting as we reach it….”

It was pretty clear that the Etch-a-Sketch machine had been called into action—back in January, when he was trying to outflank Newt Gingrich on the right, Romney vowed to deport minors—but the candidate was not willing to make it official. Instead, he tried to shift the attention to Obama, accusing him of electioneering: “If he really wanted to make a solution that dealt with these kids or with illegal immigration in America, then this is something he would have taken up in his first three and a half years, not in his last few months.”

Obama engages in electoral politics—what an outrage! Clearly, the Mittster would never stoop to such lows. As he explained to Schieffer: “Bob, I don’t have a political career. I served as governor for four years… The private sector is where I made my mark. I am in this race because I want to get America back on the right track. I don’t care about reëlection. I don’t care about the partisanship that goes on…”

Schieffer let that one go. He also let Romney repeat the largely baseless claim, one that is rapidly becoming central to the G.O.P. campaign, that Obama is anti-business and anti-free enterprise. “What’s wrong with our economy is that our government has been warring against small, medium, and large businesses,” Romney said. “People in the business world are afraid to make investments and to hire people.” A bit later, he added: “I hear it from small business people every day: Why is it that my government seems to think that I am the enemy? … Government has to be the friend of business, not the foe.” Rather than asking Romney to back up these charges with evidence, or pointing out that the Obama administration has repeatedly cut taxes for businesses small and large, Schieffer moved onto his next questions, which weren’t exactly tough.

That is Schieffer’s style, of course: he is courtly and genial, sometimes to a fault. That makes him easy to watch, and occasionally it elicits comments politicians otherwise wouldn’t make. On this occasion, though, after the initial exchange on immigration, it allowed Romney to say pretty much what he liked. He got to talk about wife Ann’s horses, one of which has been selected to represent the United States at the Olympics in dressage. He also spoke about his father George’s humble origins, and how he turned into a successful businessman and politician who said what he believed regardless of the political consequences.

Like father like son, obviously!

June 15, 2012

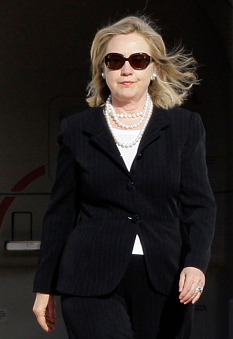

Hillary to Treasury? The Job Swap That Wasn’t

With all the fuss over Obama and Romney’s duelling speeches about the economy in Ohio yesterday, an intriguing political yarn hasn’t received much attention: early last year, Timothy Geithner tried to get Hillary Clinton to take his job as Treasury Secretary.

It’s well known that Geithner has long been keen to return to New York for family reasons. (It would be surprising if he hadn’t also grown weary of all the criticism he’s received, from liberal Democrats as well as Republicans.) In the spring of last year, according to a humdinger of a story by the Washington Post’s Ned Martel, Geithner suggested that Hillary could replace him, and the White House took the notion seriously. If Geithner had quit, the Administration would have needed a heavyweight replacement who could be confirmed quickly, and the Secretary of State met both requirements.

According to Martel, William Daley, who was then President Obama’s chief of staff, broached the idea of a job-switch with Clinton, and she “expressed cautious interest.” But a source close to Clinton that Martel quoted had a different take. This person said Hillary “listened respectfully and politely.”

I bet she did. In diplomatic circles—that is, in Hillary’s circles—to say that the Secretary of State listened to somebody “respectfully and politely” is really to say that she heard the person out without gagging or tossing her paper weight. Secretaries of State are paid to listen “respectfully and politely” to Third World dictators who run countries where the U.S. has military bases, to Afghan warlords who are on the side of the U.S.-backed government, and to former K.G.B. agents who are running Russia.

Obviously, Bill Daley doesn’t fall into any of these categories, but his intimation to Clinton that she might move from Foggy Bottom to 1500 Pennsylvania Avenue must have been about as welcome as a suggestion that she have an elective root canal. As Secretary of State, Hillary might not have any great policy successes to her credit, but the job has done wonders for her popularity. While Geithner and Obama have been battered for their handling of the economy, Clinton has been donning her sunglasses and BlackBerry and flying around the globe, burnishing her approval ratings and her credentials for a possible run at the White House in 2016.

Clinton has said that she isn’t interested in another Presidential bid and that at the end of this year she plans to retire. There’s no reason to doubt her words. But politicians have been known to change their minds and un-retire. Clinton could be another. A couple of years away from it all, with a gig at an Ivy League college, or somewhere similar, and the former First Lady might feel very differently about things. She is a Clinton, after all: politics is second nature to her.

If nothing else, 2016 is an option well worth keeping open—and replacing Geithner could well have closed it off. As Treasury Secretary, Clinton wouldn’t have been able to avoid responsibility for the weak economy. And she wouldn’t have been able to do anything about it—no more than Geither was able to do, anyway. By the start of last year, there was little the Treasury Secretary could do: the 2009 stimulus was running down, and the Republicans on Capitol Hill were blocking virtually anything the Administration suggested.

No wonder Hillary didn’t show any enthusiasm for Geithner’s idea, which ran into other objections, as well. The negotiations over the budget and the debt ceiling were getting serious, and, according to Martel, the White House was concerned about a big changeover in staff at the Treasury Department. Plus, the President wanted Geithner to stay in place.

So, Hillary stayed where she was, and everybody except Geithner was happy. He tried to be a good soldier. As Martel recalled, he appeared onstage with Bill Clinton at a meeting of his anti-poverty charity, the Clinton Global Initiative. Asked by the former President about his career plans, he said he lived for the job and would be doing it for the foreseeable future. To which Bill replied: “Good for you. That’s good for America.”

And good for the Clintons, too.

Photograph by Chung Sung-Jun/Getty Images.

June 14, 2012

How to Defeat Romney: Chain Him to the G.O.P.

With alarm growing in Democratic circles over Obama’s reëlection strategy—James Carville was the latest big-name to weigh in on the subject—I have jotted down some thoughts on where it should be focussed. But first a word about campaigns in general.

When it comes to analyzing elections, there are two basic camps: the fundamentalists and the Whigs. Fundamentalists believe that objective reality, and in particular economic reality, is the main determinant of who wins and who loses. Whigs don’t discount grand impersonal forces, such as economics and demography, but they put greater emphasis on individuals and campaigning.

As a rule, I am a fundamentalist. Jimmy Carter wasn’t run out of the White House in 1980 because he ran a lousy campaign. He lost because Americans were worried about the economy and the Iranian hostage crisis, and they had lost confidence in his leadership. Similarly, in 2008, Obama’s triumph wasn’t primarily a product of his eloquence, or his messaging. It was a reflection of the fact that Americans had tired of eight years of George Bush and the G.O.P.

TPM’s Josh Marshall is right: political analysts often overrate messaging, and campaigning generally. If a candidate dips in the polls, they say he (or she) is running a lousy campaign. If he (or she) wins, his (or her) campaign managers are hailed as geniuses. Sometimes, there is little basis for these judgements. John McCain did run a poor campaign. But even if he had run a great one, he would probably have lost anyway. Many Americans thought it was time for a change, and that was pretty much that.

Sometimes, though, campaigns do matter. Take 1988 and 2000. In both of those years, the objective circumstances dictated a close race, and superior Republican campaigns won out. George H. W. Bush and Lee Atwater sandbagged Michael Dukakis and Susan Estrich. Twelve years later, George W. Bush and Karl Rove (narrowly) outmaneuvered Al Gore, Carter Eskew, and Donna Brazile. This year looks like another one when the conduct of the campaigns will count. The incumbent has mediocre approval ratings, but so does the challenger. The economy is weak, but it was even weaker when Obama was inaugurated. On his handling of foreign policy, the President is highly regarded, but most voters are focussed on domestic matters.

So what should Obama’s message be? With job growth stalled and almost two thirds of the voters telling pollsters they believe the country is still going in the wrong direction, Obama’s campaign managers understand perfectly well that they have to frame the election as a choice between two possibly unpalatable choices rather than a referendum on Obama’s tenure. Inevitably, that means running a negative campaign and raising more doubts about the G.O.P. challenger. But it also means portraying a positive picture of the President as a dogged fighter for ordinary Americans, who is in the trenches every day battling against an extremist Republican Party.

Paul Begala remarked recently that in almost any election there are really only two campaign messages: “time for a change” and “stay the course.” In making the latter argument, Obama has to be be wary of sounding like he doesn’t get it. The official statistics may say the economy is recovering and things are better than they were when Obama came to office, but, as James Carville, Stan Greenberg, and Erica Seifert point out in a new campaign memo, many independent voters simply don’t believe it. Rather than seeking to persuade them that they are wrong, the President needs to show them two things: 1) He understands their concerns and is on their side; and 2) The outlook for the country will be a lot worse if he loses and the Republicans take over.

Going negative on Romney is pretty easy, and the process has already begun. But portraying him as an out-of-touch rich guy, and banging on about all the people he fired at Bain Capital, won’t by itself turn America against him. In this country, being rich and ruthless isn’t necessarily a barrier to electoral success; to the contrary. Mike Bloomberg is an out-of-touch rich guy and a hard-nosed businessman. A largely Democratic metropolis has reëlected him twice because it views him as a competent, straight-shooter.

The key difference between Romney and Bloomberg is that Romney hasn’t used his money to create an independent platform; he’s thrown in his lot with the G.O.P., which many independent voters view with suspicion. According to a recent NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll, fewer than a third of Americans have a positive view of the Republican Party, and just nine per cent of them have a “very positive” view. That, rather than his own record as a businessman and a governor, is Romney’s achilles heel. In addition to highlighting his record and portraying him as a soulless flip-flopper, the Obama campaign should be relentlessly depicting him as the prisoner of a rabid and obstructionist party that has consistently stymied efforts to get the economy going, and which is committed to an extremist agenda involving attacks on Medicare, Social Security, public schools, and other popular government programs.

Romney’s record in the primaries provides plenty of ammunition for such an assault. Exhibit One, of course, is his endorsement of Paul Ryan’s budget, which includes plans to partially privatize the retirement system. But he also promised to defund Planned Parenthood and PBS, retain the Bush tax cuts for the richest Americans, introduce a system of school vouchers, and force millions of illegal aliens to return to their homelands. He said “mine will be a pro-life Presidency” and “we don’t know what is causing climate change.”

Running a negative campaign doesn’t mean that you ignore your own candidate’s record, or his plans for the future; it means that you constantly seek to contrast them with his opponent and what he stands for. On this aspect, I agree with Carville, Greenberg, and Seifert, whose memo was based on focus groups they had carried out with independent voters in Ohio and Pennsylvania. These voters don’t trust Romney “because of who he is for and because he’s out of touch with ordinary people,” the memo said, “[H]e is vulnerable on the Ryan budget and its impact on people; he is vulnerable on the choices over taxes.” But the strategists noted that Obama, too, has a problem: “these voters want to know that he understands the struggle of working families and has plans to make things better.”

If this sounds a lot like saying Obama should try to be more like Bill Clinton and show that he feels the voters’ pain, that is hardly surprising: Carville and Greenberg, of course, were key figures in Clinton’s 1992 campaign. Sensing Obama’s weakness on this point, and exploiting his gaffe about the private sector doing “fine,” Romney has in recent days taken to accusing the President of being out of touch with middle-class Americans. Rather than backing down on this one, or trying to change the subject, Obama should constantly challenge Romney on the question of who best understands the concerns of ordinary Americans. Polls show that Obama already has a big lead over the Mittster in this area, which is hardly surprising. Only yesterday, the Romney campaign confirmed that, under its health-care plan, insurers would no longer be legally prohibited from refusing to cover some people with preëxisting conditions.

Verbally confronting Romney isn’t enough, though. To demonstrate his solidarity with ordinary Americans, and to ram home the message that the G.O.P. has little or nothing to offer them, Obama should spend a bit less time fund-raising and more time in Washington prodding Republicans to enact some job-creation measures, such as enabling cash-strapped states to rehire teachers and firefighters that they’ve laid off. It’s high time for another White House jobs summit, and for another jobs bill to be sent up to Capitol Hill. Let the President go up there personally and lobby for its passage. Force the Republicans (and Romney) to come out against it. Demonstrate to the American people that the President is just as determined to create jobs and defend the middle class as he is to eliminate Al Qaeda terrorists—and don’t shy away from linking the two. Americans like a fighter. In fact, how about embracing this as a campaign slogan: “President Obama: Fighting for America—at home and overseas.”

O.K., that might be a bit much, but you get the idea. As I said a couple of days ago, assuming that the economy doesn’t get any worse, Obama can win reëlection. If he is to do so, though, he needs to quit complaining about G.O.P. attacks and come out slugging, all the while reminding people what will be in store for the country if he loses and the Republicans take over.

Photograph by Jae C. Hong/AP Photo.

June 13, 2012

Tiger Woods: Force of Nature or Random Number?

A couple of months ago, after Tiger Woods won a golf tournament in Florida, I rashly said he was the justifiable favorite for the Masters, the first major championship of the year. He finished fifteen shots behind Bubba Watson. Now, after another victory in a regular tour event, Tiger is the bookmaker’s favorite for the U.S. Open, which starts tomorrow at the Olympic Club in San Francisco. But my question is this: Does that mean anything? Professional golf has almost reached a stage where, in picking a winner, you might as well close your eyes and choose a name at random.

For the first two days of the Open, the organizers have matched up six of the best players in the world. In one threesome, Tiger will be going out with his old rival Phil Mickelson and the big-hitting Watson. Teeing off in another group will be Luke Donald, Rory McIlroy, and Lee Westwood, the three top players in the official world rankings, which are based on recent form. In most individual sports—tennis, sprinting, or skiing, for example—if you put the top six players together, the victor would almost certainly turn out to be one of them. But will the winner of the Open come from these two groups? I wouldn’t bet on it.

Not very long ago, of course, Tiger dominated golf and was a justifiable favorite in every tournament he entered. Between August of 1999 and August of 2007, he won twelve major championships—a victory rate of better than one in three, which is quite remarkable. The only person who has come close to matching Tiger’s dominance over an extended period is Jack Nicklaus, who between 1962 and 1975 won fourteen majors, for a strike rate of about one in four. (Nicklaus ended his career with eighteen; Tiger’s current tally is fourteen.)

Since August, 2007, when Tiger won the P.G.A. Championship at Southern Hills, golf has changed dramatically, and he has been reduced to almost an ordinary golfer. During the last four and half years, he has just one major to his name—the 2008 U.S. Open at Torrey Pines, where he defied an injured knee to beat Rocco Mediate in a play-off. For much of 2008 and 2009, he was absent from the game, injured or repairing his personal life. But since returning to full-time play in April, 2010, he hasn’t managed to win another major—leading many to doubt whether he will ever match Nicklaus’s record.

During Woods’s absence and subsequent decline, some golf analysts predicted that Mickelson or one of the sport’s younger stars would replace him as the dominant player. It hasn’t happened. In the past seventeen majors, there have been sixteen different winners: six Americans, four Irishmen, three South Africans, an Argentine, a German, and a Korean. The only golfer to have won more than once is Padraig Harrington, who, in July and August, 2008, nabbed the British Open and the P.G.A. Championship in quick succession—and then went into a sharp decline.

One way to characterize professional golf is to say that it has reached parity—there are so many good players, and they all have a roughly equal chance of winning. A mathematical way to put it would be to say that the outcomes of big tournaments are essentially random; reputation and official rankings don’t matter. If over a series of tournaments you used a random-number generator, or a roulette wheel, to pick the winner rather than allowing the players to compete, Woods included, the outcomes wouldn’t appear very different, if at all.

That might sound ridiculous, but look at this list of the last seventeen major winners, tagged by their world ranking in the week before they won: 29, 1, 3, 3, 69, 72, 33, 110, 4, 37, 54, 13, 29, 8, 111, 108, 16. Ignore, for a moment, what these figures represent and think of them simply as a sequence of numbers selected from one to a hundred and twenty-five. Do they look like they could have been chosen at random?

Casual inspection would say not quite. Five of the numbers are between one and ten, and nine of them are between one and thirty. There appears to be a bias towards low numbers, suggesting that recent play, the basis of the world rankings, does mean something in the outcome of major championships. More formal tests of randomness are notoriously tricky. As anyone who has played around with a pair of dice knows, random-number generators often generate sequences that look non-random. For what it is worth, I carried out a quick statistical test—a “runs test”—on the list of winners, which also narrowly rejected the randomness hypotheses.

But if the outcome of major championships isn’t completely random, it isn’t very far from it. Three of the winners on the list—Darren Clarke, Y. E. Yang, and Keegan Bradley—weren’t in the top hundred when they came out on top. Three more winners—Angel Cabrera, Lucas Glover, and Louis Oosthuizen—weren’t in the top fifty. What other individual sport is there where such low-ranked competitors win so many top events? I can’t think of any.

Which brings us back to tomorrow, and Tiger. When he won the Memorial tournament at Muirfield Village in Ohio a couple of weeks ago, Woods looked liked the force of nature he once was: he striped the ball down the fairway, hit his irons close, and holed out a miracle pitch at a crucial moment. If he plays like that this week, he might well win his fifteenth major. But Olympic is a narrow and windy course, which in the past hasn’t favored the type of power golf that Tiger plays—and that Phil and Bubba play. The last two winners of Opens held at Olympic were Scott Simpson and Lee Janzen, two journeymen who hit it short but straight.

Tiger could still win. What was perhaps most impressive at the Memorial was that he seemed to have his fiery temper back under control. And for those of you who like a sporting wager, the good news is that the betting markets now reflect the reality that almost anybody could come out on top. When Tiger was at his peak, the odds on him were often less than two to one—meaning you had to bet ten dollars to win twenty. , he is the eight-to-one favorite. (Ten dollars returns eighty if Tiger triumphs.)

Rather than jinxing him again, I’m going to look elsewhere. In the two marquee groups, the straightest hitters are Donald, the world number one, who is my (not very confident) pick as the winner, and Westwood, a wry product of Nottinghamshire whom I will also be cheering on. At twelve to one, both of them represent decent value. Mickelson, at eighteen to one, and McIlroy, at twenty to one, will also have plenty of supporters.

But given the recent record, it may well be worth looking down the field and selecting another two or three straight hitters who putt well—such as Hunter Mahan, who came close to winning the 2009 Open; Jason Dufner, who is playing lights out on the regular tour; and Ian Poulter, the brightly dressed Brit—or simply putting the names of all the contestants in a hat and pulling out one. In golf, unlike in many other sports, that isn’t necessarily a bad strategy for picking a winner.

Photograph by Amy Sancetta/AP.

June 12, 2012

Obama’s Stumble: And Now for the Good News

About a month ago, I argued that it was time for President Obama’s supporters to get worried: his reëlection campaign was facing some big challenges. Since then, questioning Obama’s prospects has turned into a group sport, and so, naturally, I’m trying to look on the upside. After Rick Santorum dropped out of the race, in April, Romney had a good two months: nobody could dispute that. But he’s no Ronald Reagan or Bill Clinton—the last two challengers to defeat an incumbent. If the Obama campaign can settle on a consistent message, and if it gets a bit of luck with the economy, Romney should be eminently beatable.

Let’s start with the bad news: Karl Rove is smirking. A few weeks ago, in an op-ed piece in the Wall Street Journal, he outlined a “3-2-1” strategy that could see Romney to two hundred and seventy votes in the Electoral College. In addition to holding on to all the states that John McCain carried in 2008, the challenger needs to win back three traditional G.O.P. states: Indiana, North Carolina, and Virginia. Then he needs to win two big states that are always tossups: Florida and Ohio. Finally, he needs to nab one other Obama-leaning state—such as Iowa, New Hampshire, or Nevada. Pointing to Obama’s low approval ratings and a general tightening of the race in the opinion polls, Rove wrote, “The odds now narrowly favor a Romney win.”

At the time, that seemed like G.O.P. bravado. But last night, the Republican Svengali figure was on Fox News gloating over the fact that Obama’s lead has now narrowed even in states he would expect to win, such as Oregon and Wisconsin. Romney’s “looking good in Colorado; Iowa’s up for grabs; the latest poll in Michigan is one point,” Rove said. “There are lots of places this race could go.”

That’s true enough, but reducing the race to a “3-2-1” sound bite makes Romney’s task appear misleadingly easy. Take the “3” part. It looks like Indiana will revert to the G.O.P. column. However, even after Obama’s shift on gay marriage, which was widely expected to hurt him in the South, he is still leading in Virginia by three or four percentage points, according to recent polls. Romney has a narrow lead in North Carolina, which I’ve suspected all along that he’d end up winning, but it’s too close to call. Then there’s Ohio, where Obama is still just ahead, and Florida, which appears to be tied. For the Rove strategy to succeed, Romney has to run the tables in these four states.

That’s possible. At this stage, though, it seems unlikely. Ultimately, everything depends on what happens at the national level: swing states almost always follow the overall trend. And the national polling data still offers some encouragement for Obama.

Despite the poor jobs figures, which, together with Santorum dropping out, are what gave new life to the Romney campaign, Obama’s approval rating has held remarkably steady during the past couple of months. At the end of March, when the economy still seemed to be on the up, the Real Clear Politics poll average, which combines all the major surveys, put the President’s approval rating at 47.3 per cent and his disapproval rating at 47.6 per cent. Today, Obama’s approval rating is 48.3, and the disapproval rating is 47.8. Allowing for a bit of statistical noise, there hasn’t been any change in either figure since March.

Although there are no hard-and-fast rules, history suggests that an approval rating in the high forties puts an incumbent President in no-man’s land. It’s not high enough to assure his reëlection or low enough to assure his defeat. In May of their reëlection years, Jimmy Carter and George H. W. Bush, the last two Presidents to be defeated, had approval ratings of forty-one per cent and forty per cent in the Gallup poll. Obama’s approval rating in the same poll last month averaged forty-seven per cent—the same figure George W. Bush had at this stage in May, 2004, shortly before he easily defeated John Kerry. (In recent days, his approval rating in the Gallup tracker ticked up to fifty per cent. Today it is forty-nine per cent.) That’s the good news for Obama. However, in May, 1976, Gerald Ford also had an approval rating of forty-seven per cent in the Gallup poll, and he ended up losing to Jimmy Carter.

The message I take from these numbers is that Obama is still handily placed. Despite the efforts of the Republican attack machine to depict him as some sort of anti-American radical, most voters seems to like him personally. He scores highly for character, for understanding the concerns of ordinary Americans, and for representing their values. Lower gas prices are helping his cause, and so are the killings of senior Al Qaeda targets, Osama bin Laden included, which he will doubtless invoke again on Thursday, when he visits Ground Zero.

Deprived of their standard argument that the Democratic candidate is a wuss when it comes to national security, the Romney campaign and its allied Super PACs are seeking to portray Obama as an incompetent economic manager. This depiction clearly has some traction. Obama didn’t help himself the other day by speaking loosely about job creation in the private sector, which recently has been far from “fine.” But while the Romney campaign is successfully exploiting concerns about Obama’s stewardship of the economy, it is far from making the sale for its own candidate.

Romney is still Romney—a compromise candidate with a lot of baggage whom few Americans have great enthusiasm for. While his approval ratings have risen since March, they are still below Obama’s in most polls. Even on the economy, which is his trump card, he has yet to establish a consistent lead over the President. For example, the latest Washington Post/ABC News poll asked people whom they trusted more to do a better job handling the economy: forty-seven per cent said Romney and forty-six per cent said Obama. Asked whom they trusted more to create jobs, forty-seven per cent of respondents said Obama and forty-four per cent said Romney.

In short, the economic argument remains to be won. If Obama could somehow neutralize Romney’s strength in this arena, his advantages in other areas—the gender gap, the G.O.P.’s alienation of many Hispanics, his appeal to independents—could see him scrape through despite a weak economy. And if the economy were to pick up in the coming months, he would be virtually home free.

For this strategy to work, though, the Obama campaign needs to step up its game and settle on a clear and consistent message. Simply attacking Romney’s record at Bain Capital and as governor of Massachusetts isn’t enough. The key to success is to wage a campaign not just against Mitt, who is something of a cipher, but against the entire Republican Party, which is widely (and correctly) seen as an extremist organization. How to do this will be the subject of my next post.

Photograph by Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images.

June 11, 2012

The Spanish Bailout: A Guide for the Perplexed

The long-running euro zone crisis continues to perplex many Americans. Some see it as a moral drama: the inevitable comeuppance for a sclerotic, work-shy continent that has been spending beyond its means. Others see it as a failure of leadership: why can’t Angela Merkel and other European politicians come together and fix the problem? Still others don’t get it at all—as evidenced by the confused reaction to the news that Brussels has agreed to bail out Spain’s stricken banks. Last week, in anticipation of such a development, the S. & P. 500 rose by nearly four per cent. But when the markets opened this morning, doubts about the bailout surfaced, and stock prices fell modestly.

With a second election in Greece coming up this weekend, I’m struggling as much as anybody else to keep up with developments. But here is a quick F.A.Q. about the Spanish bailout and its aftermath, starting with today’s action on Wall Street:

Q: Isn’t the market’s reaction simply a consequence of the old trader’s rule: buy on rumor, sell on the news?

A: To be sure, there is some of that. But the sheer complexity of the situation is also playing on investors’ nerves and preventing what Europe desperately needs: some confidence that the policymakers are finally on top of things. With another election in Greece set to take place this weekend, and with many of the details of the Spanish bailout yet to be determined, the markets simply don’t know how to assess the situation. And where there is uncertainty, there is selling. Today, yields on Spanish and Italian government bonds actually rose slightly, which is the opposite of what might have been expected.

Q: Why does Spain even need a bailout? Haven’t governments in Madrid been insisting for years that the country could stand on its own two feet?

A: Yes, they have been saying that, and with some cause. Spain isn’t Greece. Until the financial crisis began, in 2008, it was running a budget surplus. The government had relatively little debt, and the banking system was held up as a model of supervision and rectitude. What did in Spain was the same thing that did in Ireland: the bursting of a big real-estate bubble, which had been fueled by low interest rates set in Frankfurt. As house prices fell and foreclosures mounted, many of Spain’s savings banks, which were big players in the mortgage market, got overwhelmed. Over the past few months, it has become clear that the savings banks can’t raise enough capital to rescue themselves, and the Spanish government can’t afford to do it: its borrowing costs have been rising rapidly, and issuing bonds to finance a bank bailout wasn’t really a practical option. Finally, late last week, Spain asked its euro partners for help.

Q: And Europe reacted pretty rapidly, right?

A: It did. From that perspective, what happened over the weekend was pretty impressive. Rather than hemming and hawing for months, which is the E.U.’s usual M.O., the other governments agreed in a single conference call to extend up to a hundred billion euros (about a hundred and twenty-five billion dollars) in credit to Spain’s banks. That’s actually rather more than many experts think the banks will need. A recent report from the International Monetary Fund put the financing requirement at forty billion euros. But E.U. officials wanted to demonstrate that they are capable of behaving in a decisive manner.

“This is a very clear signal to the markets, to the public, that the euro zone is ready to take determined action,” Olli Rehn, the E.U.’s commissioner for economic and monetary affairs, said on Sunday. “This is preëmptive action.” Many knowledgeable commentators applauded. On his blog at FT.com, my old pal Gavyn Davies noted that in providing a way to deal with the Spanish banking crisis, the weekend action “removes one of the key structural weaknesses which has undermined confidence in the Euro for months.”

Q: Where is the money coming from? German taxpayers?

A: No, or not exactly. It is coming from taxpayers throughout the euro zone. In the past couple of years, the Europeans have set up two bailout funds, which are financed by contributions from all members of the union. One of these funds, the European Financial Stability Facility, is already up and running. It provided some of the money for the earlier bailouts. The other fund, the European Stability Mechanism, is set to start operating next month. It’s not clear yet which one of these bodies will provide the money to Spain. That’s one of the things that has spooked the markets a bit: the details of the bailout haven’t yet been nailed down.

Q: Who will get the money? Will it go straight to the Spanish banks?

A: No. The E.U. will extend loans to an agency of the Spanish government that is overseeing the troubled banks, and that agency will distribute the funds as needed. But this structure raises another potential problem. Since the Spanish government will officially be taking on the loans, its overall debts, which have been rising sharply in the past few years, will rise even further—to more than a hundred per cent of G.D.P., according to some calculations. One of the risks of the bailout, therefore, is that it could transform a Spanish banking crisis into a Spanish sovereign-debt crisis. (That is what happened to Ireland.)

Q: So, does this mean that Spain is now officially a bailed-out basket case? Will it be reduced to the status of Greece, Ireland, and Portugal, with outsiders dictating its every move?

A: That’s not quite clear, either. Officially, this isn’t a bailout of the Spanish government. It is a recapitalization of the Spanish banking system by one of the European stability funds. Over the weekend, Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy insisted that his government had retained full sovereignty and wouldn’t be subjected to outside supervision. But on Monday, this picture got clouded. Wolfgang Schäuble, the German finance minister, and Joaquín Almunia, the E.U.’s competition commissioner, insisted that, as in the earlier bailouts, a “troika” of the International Monetary Fund, the European Commission, and the European Central Bank would oversee the process. “Of course there will be conditions,” Almunia told Spain’s Cadena Ser radio. “Whoever gives money never gives it away for free.”

Q: So what does it all mean? Is the euro crisis any closer to being resolved?

A: Yes it is, but there’s still a long way to go, and the outcome is hard to predict. All along, partly out of sheer contrarianism, I have stood with the minority of commentators who believed that the euro zone wouldn’t break up—that European policymakers would eventually find a way to muddle through. The Greek election and the financial deterioration in Spain have tested this hypothesis, almost to breaking point. The euro can conceivably still survive, with or without Greece, but for this to happen, a number of steps have to be taken urgently.

The first—dealing with the Spanish banking crisis—appears to be in hand. The second is sorting out what’s going to happen in Greece. Assuming the traditional center parties get enough votes this weekend to cobble together some sort of coalition, which is what the latest opinion polls are suggesting will happen, the country will hobble along inside the euro zone for at least a while longer. It will then be up to Merkel and François Hollande, the new French President, to put together, at least in embryonic form, some sort of fiscal union to complement the monetary union.

Pie in the sky? Perhaps. But Merkel did say last week, “We don’t only need monetary union, we also need a so-called fiscal union.” In Brussels, there is talk of creating the framework for a banking union, which would be a critical component of a broader fiscal union, as early as an E.U. summit later this month. The establishment of E.U.-wide deposit insurance, plus a system to allow European regulators to take over troubled banks, would help prevent problems in Spain, say, from spilling over into other countries.

Finally, the Europeans need to find some way to get their economies growing again; austerity by itself is a self-defeating strategy. We saw that in Spain, where governments of both major parties adopted budget cuts and faithfully swallowed the German medicine only to see unemployment soar and the economy fall back into recession. If the tentative economic recovery that began last year had continued, and house prices had stabilized, then the country’s banks would have been in much better shape.

Q: So what would a European growth strategy look like?

A: The general outline is pretty straightforward. It would combine structural reforms at the micro-level—getting rid of red tape, making people pay their taxes, eliminating restrictions on hiring and firing, and so on—with stimulative policies on the macro level. The European Central Bank, which has already lent a lot of money to Europe’s banks, would step up its actions—pumping more money into the economy and bringing down the value of the euro, which has already fallen in value, but not by enough. On the fiscal side, Germany and other countries that still have sound finances would allow the struggling periphery countries more leeway in balancing their budgets and repaying their debts. The E.U. as a whole, through the issue of Eurobonds, or some other financing mechanism, would launch a stimulus program directed at countries like Spain, Italy, and Ireland.

Q: And how likely is this to happen?

A. Not very. Taken as a whole, Europe still has the resources and capabilities to solve the debt crisis. Summoning the political will has always been the main barrier to progress. Even now, in Germany but also in other countries, there is a lot of public opposition to taking the costly and difficult measures that are necessary. Which is why, even though I haven’t given up on the euro, I still can’t call myself much of an optimist.

Photograph by Luca Piergiovanni/epa/Corbis.

June 6, 2012

Wisconsin: The Verdict on Obama

What to make of Scott Walker’s handy victory in Wisconsin’s recall election? As the result came in last night—Walker defeated his Democratic opponent Tom Barrett by fifty-three per cent to forty-six per cent, a bigger margin than expected—the cable pundits divided along predictable lines. On Fox News, Sarah Palin insisted it was terrible news for Obama—a rehearsal for November. On MSNBC, Lawrence O’Donnell began his show by proclaiming, “Tonight, the really big winner in the Wisconsin recall election is … President Obama.” On CNN, which usually takes the middle ground, the view was that White House couldn’t ignore what had happened. David Gergen, the dean of the Beltway School of Talking Heads, suggested that Obama’s hold on the upper Midwest, a key electoral region, might be cracking.

After a night’s sleep and a few hours thinking it over, I’m leaning toward the view that Obama will emerge relatively unscathed—but I wouldn’t push this argument too far. Walker’s victory was a significant setback for the Democratic Party, and an important victory for the big-money Republican machine the President will face in November. Coming on top of last week’s poor jobs figures, it confirms that, at least for now, the momentum is with Mitt Romney and the G.O.P.

Let’s start with Professor Palin’s narrative: “Obama’s goose is cooked.” This was a local election in which fewer than two and a half million people voted, and it was dominated by a local issue: Did the union-bashing Walker deserve booting from office before his four-year term was up? The network exit poll (which had some problems) suggested that about forty per cent of Wisconsinites strongly believed he did, and roughly an equal number strongly believed he didn’t. The middle ground—independents—went with the Governor, not out of any great enthusiasm for him, I would suggest, but because they didn’t want to hand a big victory to the public-sector unions, which had led the effort to unseat Walker.

As The Atlantic’s Molly Ball pointed out, this was a fight the unions and their progressive allies chose to have. “The idea behind the recall effort was to send a message: a warning to conservatives across the country that there was a line not to be crossed when it came to messing with the hard-earned gains of public worker unions.” Getting rid of Walker was always going to be a challenge: in all of U.S., history, just two governors have been recalled. As recently as a few months ago, it seemed like the unions might succeed in their audacious venture. In the end, they didn’t.

Obama was a bit player in this drama. Suggestions that Wisconsin may now be leaning Republican are hard to substantiate. The state hasn’t gone for the G.O.P. since Ronald Reagan’s 1984 landslide. The exit poll showed Obama leading Mitt Romney by seven percentage points (fifty-one to forty-four). Among self-identified independents, who made up about a third of the electorate, Obama’s lead was even larger: fifty-six per cent of independents said they would vote for him today.

Looking at these figures, Obama’s decision to stay away from Wisconsin—in recent weeks, he flew over the state at least twice—was ruthless, selfish, and, from his perspective, justified. After spending the past few months doing what was necessary to rally his base and raise money—taking stands on student loans, gay rights, and fair pay for women, for instance—Obama’s campaign is now preparing to reach out to independent voters, who formed the basis of his victory in 2008. Getting tagged as a lackey for the public-sector unions and what is widely seen, rightly or wrongly, as their refusal to compromise on generous benefits and restrictive practices presented an obvious danger to this strategy.

By staying above the fray, Obama preserved his image as a centrist—but at considerable cost. In refusing to stand alongside schoolteachers and state workers, many of whom earn well below fifty thousand dollars a year, he alienated unionists and progressives. This matters. Now that he is struggling to raise money from rich folks, and even many of his ordinary supporters from 2008, Obama is increasingly dependent on contributions and organizational support from the unions, which are still by far the most put-together group in the Democratic Party. In leftish circles, there will be more whispered suggestions that deep down Obama’s heart isn’t in the fight against the Koch brothers and Scott Walkers of this world. “This was a mistake,” Paul Begala said on CNN. “The President should have been out there. It’s kind of like Thanksgiving at your in-laws…. If you don’t go, there’s hell to pay.”

For Republicans, obviously, it is all encouraging—and not just because their man won. The bigger message the G.O.P. hierarchy will take from this is that the Party’s central argument, which is that government is the real problem, still resonates with the electorate. Even before the final results were in, Romney was hammering home this point. “Governor Walker has shown that citizens and taxpayers can fight back—and prevail—against the runaway government costs imposed by labor bosses,” he said in a statement. “Tonight voters said ‘no’ to the tired, liberal ideas of yesterday, and ‘yes’ to fiscal responsibility and a new direction. I look forward to working with Governor Walker to help build a better, brighter future for all Americans.”

But the Mittster needs to be careful, too. There was a reason that he, like Obama, didn’t go to Wisconsin. Opinion polls there have consistently shown that a majority of Wisconsinites support the right to collective bargaining for public-sector employees, even as they think the unions should make some concessions. The voters didn’t agree with Walker’s efforts to emasculate the unions, but fifty-two per cent of them didn’t think those efforts justified ejecting him from office two years early. If Romney now believes that yesterday’s election has given him a mandate to follow the Koch-Heritage-Cato line on workers’ rights, he could well end up playing into Obama’s hands.

Photograph by Scott Olson/Getty Images.

June 5, 2012

God Save the Queen—I Mean it, Man

If, like me, you’ve been guiltily following the Queen of England’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations on the BBC Web site, you will have enjoyed Monday night’s fireworks display at Buckingham Palace, a display of lights and sound the likes of which hasn’t been seen in London since Hitler’s bombers appeared overhead in September, 1940. Shortly after (Sir) Paul McCartney had finished singing “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” to bring the Jubilee concert to an end, the Queen lit a beacon, and giant flashes appeared from the roof of the palace to the opening strains of “Land of Hope and Glory,” Edward Elgar’s stirring paean to the British Empire, which, when he wrote it, in 1902, was busy rounding up Boer farmers and imprisoning them in what came to be known as “concentration camps.”

Land and of Hope and Glory, Mother of the Free

How shall we extol thee, who are born of thee?

Wider still and wider shall thy bounds be set

God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet

God, who made thee mighty, make thee mightier yet.

If you find it all a bit much, you aren’t alone. But critics of the monarchy, and those put off by excessive pomp and invocations of imperial might, are fighting a losing battle. Opinion polls released last week showed that the monarchy is more popular than it has been in decades: eight out of ten Britons want to retain it, while just one in eight favors establishing a republic.

I’m ambivalent. In 1977, on the occasion of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, I cracked a teen-ager’s smile when Johnny Rotten, Sid Vicious, and their fellow punk pranksters hired a barge of their own on the Thames, loaded it up with booze, floated it towards the House of Parliament, and bellowed out the first verse of their new single—“God Save the Queen / the Fascist regime / they made you a moron / potential H-bomb”—only for some of them to get arrested for disturbing the peace. In those days, the monarchy seemed to symbolize all that was restricting and stultifying and class-bound about Britain. But even then, I feel obliged to recall, the Queen herself was popular with ordinary people up and down the country. “Feck them all, the English government and the Royal Family—they raped and desolated us,” my Irish grandmother, a woman of stoutly Fenian views, would say whenever she saw the Queen appear on the television. “But, oh she’s nice. Let me see her.”

Today, after thirty years of free market-administered economic and cultural shock therapy, Britain is greatly changed—in some ways for the better, in others for the worse. But Elizabeth II is still there, wearing her tweeds, strangulating her vowels, and adhering to Woody Allen’s maxim that eighty per cent of life is just showing up. “A fantastic job she’s done,” Sir Paul, the voice of the Liverpudlian workingman despite all his fame and fortune, told the BBC shortly before the concert began. “You look at the ordinary policeman: he does twenty years, then retires. She does sixty years, and she’s still going strong. She’s amazing.”

That she is—if only for her obliviousness to much of modern life. “I don’t think she likes pop music,” Sir Paul volunteered before the start of the concert, which also featured (Sir) Elton John, Tom Jones, and Stevie Wonder. “Maybe she’ll like the opera.” That’s also doubtful. Her real passions appear to be dogs and racehorses. Still, she carries on regardless, leading the institution she refers to as “the firm” into the world of social media and reality television. “She’s a constant,” Elton John said. “She’s not changed. She doesn’t follow any fads. I remember watching the coronation when I was six years old, and she’s been the same kind of woman ever since.”

John, a veteran of royal occasions—at Princess Diana’s funeral, he sang his adapted version of “Candle in the Wind”—didn’t quite have it right. In response to the public outcry following Diana’s death, when the royal family made the disastrous decision to stay at their Scottish estate until the funeral rather than returning to London, the monarchy has changed its public-relations strategy, putting on display a somewhat more human and modern aspect. The presence of two telegenic young princes, Harry and William, has been a great boon to this venture. But even their father, Prince Charles, whose age now reflects his “old fogey” persona, has been making an effort. Last month, he read the weather forecast during a visit to BBC Scotland. On Friday, he was back on the Beeb, kicking off the Jubilee weekend by presenting a documentary about his mother, which included lots of previously unseen film footage, including some of a family vacation on the Norfolk beach in 1957.

As social history and as a glimpse inside Buckingham Palace, Balmoral, and other royal buildings that are usually off-limits to the public, it was an interesting show. As a monarchist ploy, it was fiendishly effective—as was the wheeze of giving people two days off work to enjoy the Jubilee celebrations, which wound up on Tuesday afternoon with a thanksgiving service at St Paul’s Cathedral and Royal Air Force jets whizzing by Buckingham Palace in formation. “[I]n all her public engagements, our Queen has shown a quality of joy in the happiness of others

showing honor to countless local communities and individuals of every background and class and race,” Dr. Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, said in his sermon. “She has made her public happy.”

Let us stipulate that this was merely one pillar of an encrusted British establishment praising another. Yet there was still truth in the Archbishop’s words. Republicans are on the defensive; the forces of social conditioning are at work; and the British monarchy, for all its absurdities, appears to have a bright future. In my hometown of Leeds, one of my younger brothers, who is no fan of paying taxes to support the Windsors, was invited to a “Stuff the Jubilee” garden party. His wife, my sister-in-law, objected to him taking their six-year-old daughter. The girl had been learning about the monarchy in school and she was excited about the celebrations: there was no point in upsetting her. My brother gave in. Rather than stuffing the Queen, he attended a Jubilee street party in her honor. But his sympathies, and some of mine, remained with the Sex Pistols.

Photograph by Ian Gavan/Getty Images.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers