John Cassidy's Blog, page 90

September 6, 2012

Obama the Front-Runner Plays it Safe

After the passionate personal testimonial from his wife and the extended master class presented by his Democratic predecessor earlier this week, Barack Obama gave a much more orthodox and workmanlike political address on Thursday night. Carefully crafted to rally his Democratic base while also appealing to to independent voters, it was the speech of a front-runner who thinks he can win if the current dynamic is maintained, and he may well be right.

The speech was short on new ideas and policy proposals, and shorter still on rah-rah attack lines. The delegates in the audience, who had stood and cheered through much of Bill Clinton’s forty-eight-minute lecture, spent most of Obama’s speech, which was quite a bit shorter, rooted to their chairs. The first big cheer came more than twenty minutes in, and it was in response to a line that was pretty innocuous: “I am no longer a candidate, I am the President.”

Aware of the perception that he is arrogant and distant, Obama struck a humble tone throughout, saying he was “mindful of my own failings” and citing Lincoln’s famous quote that he had been driven to his knees many times “by the overwhelming conviction that I had no place else to go.” Rather than claiming, as Clinton had done the night before, that his economic policies were working and that things were getting better, he said, “I won’t pretend the path I’m offering is quick or easy. I never have. You didn’t elect me to tell you what you wanted to hear. You elected me to tell you the truth. And the truth is, it will take more than a few years for us to solve challenges that have built up over decades… But know this, America: our problems can be solved.”

His rhetoric soared a bit toward the end, where he repeatedly said that he hadn’t given up on the hope in the future, and in the American people, that he had stressed in 2008. But this was Obama eager to avoid the impression that he was out of touch, oblivious to the challenges that many voters face. He presented himself as a President chastened but also seasoned by the challenges of the past four years, a President still ready and eager to lead the United States to a better, more prosperous future, and to head off the dreadful fate that would befall the nation if the Republicans took over.

In short, Obama played it safe. From the beginning, his campaign strategy has been based upon trying to turn the election into a choice between two rival visions, and ideologies, rather than a referendum on his own record. Since he is maintaining a narrow lead in the polls and a slightly bigger one in some of the key swing states, he clearly saw no need to divert from that strategy at this point. Averring that he was sick of all the trivialities and negative advertising, a considerable stretch for someone whose campaign has spent many millions of dollars attacking Mitt Romney and his record, he said, “When all is said and done, when you pick up that ballot to vote, you will face the clearest choice of any time in a generation…the choice you face won’t be just between two candidates or two parties.”

Indeed, Obama was so keen to make the choice argument, and to avoid playing into his opponent’s referendum narrative, that he barely paused to defend his own record on the two biggest initiatives of his first term: the stimulus and the health-care reform. Whereas Bill Clinton had engaged the Republican attacks on these issues directly, and convincingly, Obama chose to make his stand on more favorable grounds: foreign policy, the auto bailout, student loans, and the elimination of Osama bin Laden.

The Obama campaign had depicted the speech as an opportunity for him to lay out an economic agenda for the next four years, but most of the goals (not promises) he listed were familiar or modest, or both: the creation of a million new manufacturing jobs by 2016; halving oil imports by 2020; hiring a hundred thousand new math and science teachers by 2022; and reducing the deficit by cumulative four trillion dollars over the next decade.

One of the strongest parts of the speech came when Obama explained what he wouldn’t do rather than what he would:

I refuse to ask middle class families to give up their deductions for owning a home or raising their kids just to pay for another millionaire’s tax cut. I refuse to ask students to pay more for college; or kick children out of Head Start programs, to eliminate health insurance for millions of Americans who are poor, and elderly, or disabled, all so those with the most can pay less. I’m not going along with that. And I will—I will never turn Medicare into a voucher.

This was Obama playing the traditional Democrat, the protector of the young, the elderly, and the economically challenged. He coupled it with shout-outs to key elements of his winning coalition in 2008: women, Hispanics, gays, and students. With the race so tight, turnout is going to be key, and Obama knows he needs to address the “enthusiasm gap,” which Jim Messina and David Axelrod will insist to their dying days played no role in the last-minute decision to switch Obama’s speech from an eighty-thousand seat-outdoor stadium to the relatively modest Time Warner Cable arena.

Toward the end, the cameras managed to pick out one or two delegates with tears in their eyes. But this wasn’t really that type of speech. Compared, for example, to the stirring oration that Representative John Lewis of Georgia, a lion of the civil-rights era, gave much earlier in the evening, in which he lambasted Republican voter-suppression efforts, it was fairly tame stuff. Even when he attacked his opponent, he did it in a low-key fashion. If the Obama campaign believed that he was in trouble, he may well have raised Romney’s record at Bain Capital and his failure to release more tax returns, but here he was content to wield the stiletto rather than bludgeon, noting, “You might not be ready for diplomacy with Beijing if you can’t visit the Olympics without insulting our closest ally.”

None of this implies it was a bad speech: it just means that it was carefully modulated and tactically driven. For an incumbent President running for reëlection in objectively unfavorable circumstances, who has somehow managed to build up a steady if narrow lead in the polls, it may have been precisely what was needed. Don’t upset the applecart, show some modesty, keep banging on about the extremist Republicans. And who knows, you might just well end up as the first President in the modern era to get reëlected with the unemployment rate at eight per cent or more.

Which brings us to the employment report for August, due to be released less than twelve hours after the President spoke. A good jobs number could do more for Obama’s prospects than this speech, competent as it was; more, even, than Bill Clinton’s peroration. A bad number, on the other hand? Well, let’s just see what the figures are.

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read Ryan Lizza on Clinton’s speech; Julián Castro’s keynote address and the relationship between President Obama and Bill Clinton; John Cassidy on Michelle Obama’s convention speech and Obama’s and Paul Ryan’s false statements about the economy; Amy Davidson on what Bill Clinton didn’t say; the First Lady’s speech, the gay-rights platform, and whether Democrats are better off than they were four years ago; Hendrik Hertzberg on renewed Democratic enthusiasm; and Alex Koppelman on Obama and the American Dream.

Photograph by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

Is Barack Obama a Secret Clintonite?

A day later, and Charlotte is still buzzing about Bill Clinton’s epic summation for the defense in the case of Republicans vs. Barack Hussein Obama. Evidently, I was in a minority of one in thinking it was too long for a prime-time television event. The conventional wisdom is that it was a masterpiece, and since the entire role of party conventions these days is to influence the conventional wisdom, it was a masterpiece, and my instant assessment was wrong. The editors of the Weekly Standard, hardly friends of the Democrats, said that the speech gave Obama everything he could have wanted. Alex Castellanos, a G.O.P. consultant, even suggested that Clinton had won the election for the Democrats.

That’s going too far. Just how much Clinton’s ringing endorsement will influence the crucial swing voters in places like North Carolina, Florida, and Ohio remains to be seen. But in persuading him to follow Michelle Obama as a headline speaker, Jim Messina, Obama’s campaign manager, put on the strongest show possible. Boasting approval ratings well into the sixties, Michelle and Bill are two of the most popular Democrats in the country (the other big name at their level just happens to be Bill’s wife), and their speeches complemented each other. Michelle testified to Obama’s values and character; Bill said his policies have been more successful than many people realize, which happens to be true.

The sight of the two men hugging will put to rest, at least for now, the talk about their rivalry and mutual wariness. But it raises a larger issue that gets discussed a lot less often, and which goes to what the President will say in his own speech tonight: Is Obama a Clintonite? If not, what is he? A centrist? A progressive? An “Obamaite”—whatever that term means?

My theory is that the two men are more similar than they perhaps realize, and that the obvious differences in their characters have disguised this fact. Both of them are essentially moderate liberals who favor traditional Democratic goals—fostering equal opportunity, strengthening the safety net, reducing poverty and inequality, and making America a more enlightened place. But while Clinton was essentially a liberal realist, Obama, when he entered the White House, was a liberal utopian, a messianic figure who harbored dreams of moving beyond partisanship—or, at least, that was how his campaign portrayed him. Ever since the high hopes he inspired were, inevitably, dashed, he has been looking around for a new way to frame his arguments, mobilize his supporters, and leave a lasting legacy. Recently, in embracing the language of early-twentieth-century progressivism, he has made some progress in this direction. But Obamaism remains far from a finished article.

A product of the nineteen-seventies and eighties, a period of despair for Democrats, Clinton was a self-described “New Democrat.” He recognized that large swaths of the American public had lost trust in the party, that free-market economics was in the ascendency, and that progressives, if they wanted to achieve any of their goals, would have to reach an accommodation with the conservative backlash that spawned Reaganism and Thatcherism. If you wanted to win support for providing income subsidies for the working poor, you had to force the unemployed to work for their benefits. If you wanted to raise taxes on the rich, you had to cut taxes for the middle class. And if you wanted to expand government programs in areas like education and energy conservation, you had to couple it with efforts to streamline the federal bureaucracy and reduce the deficit.

Back in the late eighties and early nineties, a lot of liberals didn’t want to hear this. (Jesse Jackson, for one, memorably dismissed Clinton and Al Gore as southern boys in suits.) But the centrist approach proved highly successful: Clinton won two elections; across the Atlantic, the like-minded Tony Blair won three. Both men presided over periods of rapid economic growth and low unemployment. As Clinton reminded us last night, it was the “longest peacetime expansion in history.”

Despite its success, however, Clintonism was essentially a defensive creed, which sought to preserve the essentials of the New Deal and the Great Society, while making a few modest gains around the margins. Obama, too, faces right-wing opponents who would tear down the creations of Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson, but it isn’t clear that he sees his situation with the same gimlet eye that Clinton brought to bear. Or, it wasn’t until recently. Since the House Republicans humiliated him last summer, during the debate about the debt ceiling, he has started to sound and act more like his Democratic predecessor: pillorying the Republicans as do-nothing extremists; reaching out to key elements of the Democratic Party coalition, such as gays and Hispanics; and concentrating on some relatively minor but concrete measures that don’t depend on G.O.P. approval, such as reforming the student-loan program.

Republican suggestions that Obama is some sort of quasi-socialist are absurd. On the big issues, he has governed as a center-left President who recognizes the creative power of the market but also recognizes that markets can fail, and that when they do it is up to the government to step in and affect a fix. Clinton recognized this, too—recall his failed effort to reform the health-care system. Had he been in office since 2008, I am sure he would have done many of the same things that Obama has done: introduced a big stimulus package, tightened up financial regulations, and made another attempt to reform health care. It shouldn’t be forgotten that almost all of Obama’s senior economic advisers are ex-Clintonites: Tim Geithner, Larry Summers, Peter Orszag, Nancy-Ann DeParle, Gene Sperling.

On foreign policy, too, there is a lot of continuity, beginning with the fact that Obama picked a Clinton as his Secretary of State. The onset of the post-9/11 era makes comparisons a bit tricky. Obama has completed the drawdown in Iraq that was begun under his Republican predecessor. He launched and then truncated a surge in Afghanistan that appears to have failed. And he maintained (and, in some aspects, such as drone warfare, intensified) the so-called “war on terror.” Clinton, ever sensitive to the charge that Democrats are soft on national security, would probably have behaved in a similar manner.

Their rhetoric aside, where Clinton and Obama have differed is in their approach to Wall Street and social issues. With Bob Rubin at his side, Clinton bought into the Wall Street view of regulation and innovation, which, all-too-often, sees the government as an annoying hindrance. Even today, he sometimes balks at criticisms of the financial sector, as evidenced by his rebuke of the Obama campaign for its decision to focus on Mitt Romney’s record at Bain Capital. Obama, since his initial big speech about the economy at the Cooper Union, in March 2008, has generally taken a more skeptical approach to Wall Street, at least in his public utterances, for which he has been rewarded with a sharp drop in campaign donations.

On social issues, Obama has gone quite a bit further than Clinton or any of his other Democratic predecessors—ending the policy of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and coming out in favor of gay marriage. But this, too, can probably be put down to Clinton’s political realism, and his sensitivity to the concerns of working-class voters, white and black. In introducing Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and signing the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act, he was making the judgement that America wasn’t yet ready to embrace the positions that many highly-educated urban liberals supported. And who is to say he was wrong? Obama, too, thought long and hard about openly embracing gay marriage. It wasn’t until Governor Andrew Cuomo had taken the lead, with no damage to his poll numbers, that he moved.

Many of the differences in emphasis between the two Presidents can be explained by the circumstances they inherited. Clinton took over as economic growth was picking up, and he governed in good times, partly of his own making. Obama, facing the deepest slump since the nineteen-thirties, was more or less obliged to make the case for government activism and government programs. To his credit, he didn’t abandon this argument after the setback of the 2010 midterms. (It was, remember, the disaster of the 1994 midterms that prompted Clinton to embrace welfare reform and say the era of big government was over.) Indeed, he has recently gone further in this direction, talking about the need to confront inequality and exclusion in a way that many Democrats have shied away from since the Reagan years. In Osawatomie, Kansas, last December, he evoked the memory of Teddy Roosevelt and described the drive to restore economic growth and economic fairness as “the defining issue of our time.”

With the Republicans effectively controlling Congress for the past two years, Obama hasn’t been able to turn his progressive arguments into actual measures. But at least in principle, there is the kernel of a governing philosophy that would move the Democrats beyond Clintonism and onto the offensive—a governing philosophy that recognizes the creative power of markets and the limits of government, but which also prioritizes fairness and long-term sustainability, and which takes a more skeptical approach to self-serving arguments presented by big business. This is the sort of progressivism that Elizabeth Warren talked about on Wednesday night in a speech that also cited Teddy Roosevelt, and it is a progressivism that Clinton would surely support.

In fact, Obama’s recent statements represent a return to the sort of populist rhetoric that Clinton used in 1992, when he inveighed against the betrayal of the middle class and called for a “New Covenant.” And Obama’s income-tax proposals would simply restore the top rate to what it was during the Clinton years, before George W. went to Washington. Temperamentally, the two Democratic Presidents may be as different as can be, but on matters of substance they support many of the same things. Indeed, it is hard to think of a big issue that divides them. Now that the two of them have made up, they might just make a formidable team.

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read Ryan Lizza on Clinton’s speech; Julián Castro’s keynote address and the relationship between President Obama and Bill Clinton; John Cassidy on Michelle Obama’s convention speech and Obama’s and Paul Ryan’s false statements about the economy; Amy Davidson on what Bill Clinton didn’t say; the First Lady’s speech, the gay-rights platform, and whether Democrats are better off than they were four years ago; Hendrik Hertzberg on renewed Democratic enthusiasm; and Alex Koppelman on Obama and the American Dream.

Official White House Photo by Pete Souza

Clinton Talks Up Obama—and Talks and Talks

In the most surprising development since Dmitri Medvedev endorsed Vladimir Putin for the Russian presidency, the last Democratic President took the stage on Wednesday night and—hold the front page—delivered a lengthy and rousing appeal for the reëlection of the current Democratic President.

As thousands of fired-up journalists and boozed-up delegates—sorry, please reverse those adjectives—looked on in awe, the man they used to call “The Comeback Kid” explained that his wife, the Secretary of State, would love to have been there to endorse her boss, but she was too busy recruiting a campaign manager and Michelle Obama’s speechwriter for her 2016 campaign. That plus the fact that she had been on the horn all day trying to explain to the Israelis that the decision to excise the part of the Democratic Party platform which recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, a decision hastily reversed shortly before Clinton spoke, was a low-level error rather than a Presidential “screw you” to Sheldon Adelson, or a signal of encouragement to Iran’s nuclear scientists.

Actually, Clinton didn’t say any of this, or anything like it. Hillary was in East Timor, and I doodled the previous paragraph as Bill was explaining at great length how Barack Obama hadn’t raided Medicare, or abandoned the work requirement for welfare, or done any of the other dastardly things that Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan have been claiming he’s done. Making things up during a headline speech on the second night of a convention is a gross dereliction of journalistic duty, I readily concede. But honestly, by that stage, roughly forty minutes into an epic speech scheduled for twenty, my shorthand had given up, and I’d decided to wait for the full transcript.

The operator of the teleprompter was evidently having similar problems. Numerous times during Clinton’s peroration, which eventually drew to a close just before eleven-thirty, the machine appeared to have conked out, the same words frozen on the screen. It hadn’t backed up; it had simply stopped because the former President had departed from this prepared remarks, which were pretty long to begin with, and ad-libbed to his heart’s content.

At half the length, or a bit shorter, Clinton’s speech would have been extremely effective. Even as it was, it was certainly memorable. Preceded by Elizabeth Warren, who delivered a shorter but equally forceful defense of Obama’s record, he described the President, with whom he has had a famously wary relationship, as “a man who is cool on the outside but who burns for America on the inside.” He eloquently defended Obama’s communitarian economic philosophy, his failed attempts to foster bipartisanship, and his economic record, noting: “No President—not me or any of my predecessors could have repaired all the damage in just four years. But conditions are improving and if you’ll renew the President’s contract you will feel it.”

But rather than stopping there, Clinton went on, and on. By the end, he sounded a bit like an insurance salesman who has been invited into the parlor to describe his policies and who refuses to leave. He detailed the success of the auto bailout, pointing out that there are now a quarter of a million more people working in the auto industry than there were when the car companies were rescued. He explained the meaning of Obama’s student-loan reforms—“no one will have to drop out of college again for fear they won’t be able to pay their debts.” He defended the regulations designed to improve fuel economy, saying it would “cut your gas prices in half, your gas bill.” He poked fun at Paul Ryan’s claims that President Obama is gutting Medicare: “It takes some brass to attack a guy for doing what you did.” He lambasted Ryan’s running mate: “We simply cannot afford to give the reins of government to someone who will double down on trickle down”.

Several times, he said. “Listen to me

.” At one point, he said that when people ask him how he balanced the budget, he always gave a one word answer: “arithmetic.” But that can’t be right; he has seldom been known to give a one-paragraph answer to anything, let alone a one-word answer. Twenty-four years ago, in Atlanta, he gave a similarly elongated speech in formally nominating Michael Dukakis, and when he finally said, “in conclusion,” cheers broke out around the hall.

That didn’t happen this time, of course. Making his seventh consecutive appearance at a Democratic Convention, he is now the unofficial patron saint of the Party, a much-loved figure who can do no wrong. The people in the hall cheered (almost) all of his quips, and when he finally wound it up and Obama appeared to hug him and put his arm around his shoulders, they cheered wildly. Democrats everywhere will have been loving it all. But how many of the white, working-class men in Ohio and Michigan and Florida that Clinton was supposed to be courting were still watching?

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read Ryan Lizza on Clinton’s speech; Julián Castro’s keynote address and the relationship between President Obama and Bill Clinton; John Cassidy on Michelle Obama’s convention speech and Obama’s and Paul Ryan’s false statements about the economy; Amy Davidson on what Bill Clinton didn’t say; the First Lady’s speech, the gay-rights platform, and whether Democrats are better off than they were four years ago; Hendrik Hertzberg on renewed Democratic enthusiasm; and Alex Koppelman on Obama and the American Dream.

Photograph by Charles Dharapak/AP Photo.

September 4, 2012

The “New Obama”: Michelle Keeps Hope Alive

The climax of the first night of the Democratic National Convention was billed as an opportunity for Americans to meet the new Obama—a Hispanic Obama, Julián Castro, the thirty-seven-year-old mayor of San Antonio—and for the First Lady, Michelle Obama, to say some nice words about the old Obama, the rapidly graying one who is running roughly even in the polls with a stuffed shirt called Mitt Romney.

It didn’t work out like that. Castro, after a slow start, got off some choice shots at the Mittster, and generally gave a good account of himself, but the First Lady, in a bravura performance, completely overshadowed him. Combining personal testimonials (“I love my husband even more that I did four years ago”) with behind-the-scenes details from the White House (the President “strategizing over middle-school friendships” with his daughters) and Reaganesque rhetoric (“never forget that doing the impossible is the history of this nation”), she threw off the cloak of domesticity that she has been wearing for the past three and a half years and emerged as a major figure in her own right. By the end of her speech, Twitter was full of speculation about her running for President some day, though Jodi Kantor, who wrote a book about the Obamas, said that it would never happen: if Michelle ran for office, Kantor said, she would eat her book.

There’s nothing like a story-starved press pack to get ahead of itself. For now, let us simply state the obvious: Michelle Obama gave a speech that her husband, the speechifier, would have been proud of. After a night of enthusiastic but predictable denunciations of Romney’s Swiss bank accounts and laudations for Obama’s decision to save the auto industry, end Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, and pass universal health care, she lit up the Time Warner Cable Arena, home to the Charlotte Bobcats. When she left the stage, many people in the audience were calling for an encore, and so, surely were her husband and daughters, who were watching her on television from the White House.

Inevitably, comparisons will be made with Ann Romney’s speech in Tampa last week. Facing the tough task of humanizing a financial engineer who made hundreds of millions of dollars by piling debt on companies and wringing efficiencies from their operations, Ms. Romney performed admirably. But Ms. Obama outdid her. In part, that was because her speech, which presumably was written for her, was superior.

Beginning by offering praise for the many outstanding Americans, particularly military veterans and their families, she has met during the past four years, she arced through her personal history with Obama, her initial reluctance to move to Washington, the hard-working father who inspired her, the hard-working grandmother who inspired her husband, and finally back to the life she and her husband have led in the White House, where, “He didn’t care whether it was the easy thing to do politically—that’s not how he was raised—he cared that it was the right thing to do.”

It wasn’t just a good speech, it was a dramatic performance. Clad in a very pretty pink and silver dress designed by Tracy Reese, which showed off her well-toned arms, she appeared on the bright blue stage to a two-minute standing ovation. After a couple of early stammers, which some folks on Twitter suggested were strictly for effect, she spoke seamlessly and flawlessly. Although she was standing in front of a teleprompter, she had clearly memorized the speech to the point where she appeared to be speaking spontaneously.

I thought the best bit came when she talked about the values their parents and grandparents had imbued in her and Barack. She retold the story of her father, who defied multiple sclerosis to get up at dawn each day and work at a city water plant, where he earned enough to help pay for his share (after financial aid and loans) of his children’s college-tuition fees.

And every semester, he was determined to pay that bill right on time, even taking out loans when he fell short. He was so proud to be sending his kids to college and he made sure we never missed a registration deadline because his check was late. You see, for my dad, that’s what it meant to be a man. Like so many of us, that was the measure of his success in life—being able to earn a decent living that allowed him to support his family. And as I got to know Barack, I realized that even though he’d grown up all the way across the country, he’d been brought up just like me.

It was powerful stuff, and it didn’t stop there. She went on:

We learned about dignity and decency—that how hard you work matters more than how much you make . That helping others means more than just getting ahead yourself. We learned about honesty and integrity—that the truth matters . That you don’t take shortcuts or play by your own set of rules and success doesn’t count unless you earn it fair and square. We learned about gratitude and humility—that so many people had a hand in our success, from the teachers who inspired us to the janitors who kept our school clean . And we were taught to value everyone’s contribution and treat everyone with respect.

Those are the values Barack and I—and so many of you—are trying to pass on to our own children. That’s who we are.

In the final part of the speech, she drew the threads together, insisting that her husband, in fighting for things like equal pay for women, universal health care, and a thriving auto industry, was simply doing what he had always done.

Barack knows the American Dream because he’s lived it and he wants everyone in this country to have that same opportunity, no matter who we are, or where we’re from, or what we look like, or who we love. And he believes that when you’ve worked hard, and done well, and walked through that doorway of opportunity you do not slam it shut behind you . You reach back, and you give other folks the same chances that helped you succeed.

So when people ask me whether being in the White House has changed my husband, I can honestly say that when it comes to his character, and his convictions, and his heart, Barack Obama is still the same man I fell in love with all those years ago. He’s the same man who started his career by turning down high paying jobs and instead working in struggling neighborhoods where a steel plant had shut down, fighting to rebuild those communities and get folks back to work . Because for Barack, success isn’t about how much money you make, it’s about the difference you make in people’s lives.

If that last line was an indirect jab at her husband’s opponent, it was about the only one in the speech. Rather than trying to tear down Romney and the G.O.P., she tried to elevate her husband and his works, assuring disappointed Democrats and independents that, she, for one, still had faith in him. Obviously, it was a one-sided speech. She glossed over Obama’s comfortable upbringing in Hawaii, failed to mention his role in bailing out Wall Street banks, and didn’t mention the housing crisis, the soaring deficit, or the fall in median income. But that was hardly her role. She came to bolster Obama, and in doing so she demonstrated that effective speeches don’t have to be full of attack lines. Direct statements, sincere expressions of personal feeling, and a bit of poetry can do the job just as well.

So, let us praise Michelle Obama, a tall, glamorous, intelligent, and strong-minded daughter of the Windy City who finally came into her own, without any apologies or histrionics. She may well be sincere when she says that she has no political ambitions of her own. But after Tuesday evening, the option will always be there.

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read Cassidy on Obama’s and Paul Ryan’s false statements about the economy; Ryan Lizza on Julián Castro’s keynote address and the relationship between President Obama and Bill Clinton; Amy Davidson on the gay-rights platform and whether Democrats are better off than they were four years ago; and Alex Koppelman on Obama and the American Dream.

Photograph by J. Scott Applewhite/AP Photo.

The Lying Game: Obama and Ryan Revive National Pastime

After a few days rest in a mercifully Internet-free location and a quick hop from LaGuardia, I’m down here in North Carolina, birthplace of many noted Americans, from Ava Gardner to John Coltrane to Billy Graham. The last time I was here on a story was 1990, when another famous son, Jesse Helms, was busy seeing off the challenge of Harvey Gantt, a former mayor of Charlotte, who was bidding to become the first African-American senator to be elected in the South since Reconstruction. That was the campaign, you may recall, in which Helms, already facing charges of intimidation and attempted voter-suppression, ran a last-minute television ad showing a white pair of hands tearing up a rejection letter from a company that, according to the voiceover, had given the job to a less-qualified minority. In a state that then, as now, was more than two-thirds white, Helms squeezed home by five points and remained in the Senate for another thirteen years, until ill-health forced him to retire.

I mention this history merely as a reminder that employing questionable campaign tactics, and sticking it to one’s opponents in ways that (how to put it?) stretch the truth in imaginative ways, are hardly new developments in American politics. Negative campaigning is as American as baseball, and with the polls just about even coming out of Tampa, both sides are eagerly partaking in the ancient pastime of fibbing and dissembling for political advantage.

Thanks in part to the posts of my New Yorker colleague Nicholas Thompson, we know all about Paul Ryan’s bogus claim to have run a sub-three-hour marathon. Gideon Rachman, in his column in the Financial Times this morning, suggested that the Ryan revelation could tip the election in Obama’s favor, writing: “It would be nice to believe that the U.S. election will ultimately turn on this profound debate about the role of the government. But it is just as likely to turn into a battle of the gaffes: Obama’s ‘you didn’t build that’ against Ryan’s three-hour marathon.”

Call me an old-fashioned fundamentalist, but I doubt Ryan’s idle boast—amusing and revealing of the man as it was—will play such a key role come November. After all is said and done, the election will come down to economics, I reckon. And the two campaigns evidently think the same way. In the runup to the President’s speech this Thursday, in which he will seek to rekindle some of the spirt of 2008, it is on the economic front that both sides are rolling out their biggest whoppers.

In Ohio yesterday, according to a report in the Times that I read on the plane, Obama said this of his rival: “The problem is everybody has already seen his economic playbook, we know what’s in it. On first down, he hikes taxes by nearly two thousand dollars on the average family with kids in order to pay for a massive tax cut for multi-millionaires.”

Ryan, meanwhile, was in Greenville, North Carolina, which isn’t far from here, where he delivered a little history lesson: “The President can say a lot of things, but he can’t tell you you are better off. Simply put, the Jimmy Carter years look like the good old days compared to where we are now.”

Let’s start with Obama. Since he’s nine years Ryan’s senior, and he is the POTUS, it seems reasonable to expect his statements, even during a campaign, to bear some semblance to the truth. In this instance, they didn’t. Romney has repeatedly stated that he won’t raise taxes on families of moderate incomes. For instance, in an interview with Fortune, he said: “I will under no circumstances raise taxes on the middle class.”

What, then, was Obama talking about? It turns out he was repeating a claim from one of his new campaign ads, which says, “Under the Romney plan, a middle-class family will pay an average of up to two thousand dollars more a year in taxes.”

Evidently, the basis for this claim was a detailed study by three economists affiliated with the Tax Policy Center which came out at the start of August. As I’ve said before, it was essentially an accounting exercise, which took seriously all of the things that the Romney campaign has promised to do and tried to figure out what would have to happen to make them mutually consistent.

For those of you who have forgotten, Romney says he would cut income-tax rates across the board by a fifth and make up for the lost revenue by eliminating, or scaling back, some popular tax breaks, such as the deductions for mortgage-interest payments and local taxes. At the same time, though, he would leave alone some big tax breaks that benefit the rich, such as the ultra-low rates on income from dividends and capital gains. The study’s main contribution was to point out that Romney’s arithmetic doesn’t add up. If he is serious about his plan being revenue neutral, he will have to make very deep cuts to the tax breaks enjoyed by middle-class families, so much so that some of them could end up paying more to the federal government, on net. How much more? The study said that taxpayers earning less than two hundred thousand dollars a year could face a five-hundred-dollars annual tax increase.

Now a tax increase of five hundred dollars is a tax increase, but clearly it isn’t two thousand dollars. That is hard to argue with. The only figure in the study I can see that approximates the one the President used is eighteen hundred dollars. That is the potential tax hike that families who earn between $200,000 and $500,000 could face if all of the assumptions in the Tax Policy Center report were satisfied. But are these families middle class? In another context, Obama says they aren’t. In attacking the Bush tax cuts, he has pledged to repeal them for families earning more than $250,000.

That’s one thing. Moreover, the very idea of using the Tax Policy Center study to accuse Romney of planning to raise taxes on the middle class is a tendentious one. It’s a big leap from saying Romney’s arithmetic doesn’t add up to accusing him of planning to raise taxes on the middle class. Given the political damage that the G.O.P. candidate would suffer if he followed such a course, it seems far more likely that he would break another one of his pledges instead, such as the promise to make his tax reform revenue neutral. Politically, it would be much easier to introduce the tax cuts, eliminate some, but not all, of the sensitive tax breaks, and allow the budget deficit to rise as revenues fell. If the President was accusing Romney of being a “chicken hawk” on the budget, he would be on much firmer ground. But he clearly thinks it’s more effective to accuse his rival of planning a covert tax hike.

Now on to Ryan, who you might think would be feeling a little chastened. Evidently not. With his running mate taking a few days off to prepare for the Presidential debates, the Republican Vice-Presidential candidate is playing the time-honored role of attack dog, in this case seeking to tie Obama to Jimmy Carter, a President whose achievements have been virtually forgotten, and whose very name is used as a synonym for economic failure.

So what are the facts? In July, 1980, the unemployment rate was 7.8 per cent. In July, 2012, it was 8.3 per cent. Score one for Ryan. But in July, 1980, the inflation rate was 13.1 per cent. Today, the inflation rate is running at 1.4 per cent. Score one for Obama. Score more than one, in fact. If you add the inflation rate and the unemployment rate together, you get the so-called “misery index.” At this point in 1980, it stood at 21.1. Today, it is 9.7.

What is more, in 1980 the unemployment rate was headed up. Seeking to bring down inflation, which was widely seen as threatening to spin out of control, Paul Volcker, then the chairman of the Federal Reserve, was busy raising interest rates—by June, 1981, the federal-funds rate would reach twenty per cent. Volcker succeeded, but only by bringing about a deep recession. The unemployment rate rose for three more years, and by the summer of 1983 it had reached 10.1 per cent. Today, we are at the other end of a recession. Unemployment is trending down, albeit not quickly enough.

In short, Ryan is wrong. The last days of Jimmy Carter’s Presidency were marked by rising unemployment, soaring inflation, and a widespread belief that things were only getting worse. That is why he lost to Ronald Reagan. It is perfectly understandable for Ryan to want history to repeat itself, but in saying things are worse now than they were in 1980, he is using the same tactics as Obama: punch low and often. If you get called for it, shrug and take another swing. That, after all, is the American way. (And the way in many other countries, too.)

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read Ryan Lizza on the relationship between President Obama and Bill Clinton; Amy Davidson on the gay-rights platform and whether Democrats are better off than they were four years ago; and Alex Koppelman on Obama and the American Dream.

Photograph by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

August 31, 2012

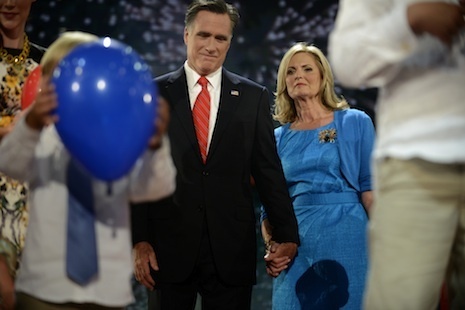

Tampa Wrap: A Well-Orchestrated G.O.P. Sham

By 2:30 A.M. on Friday morning, construction crews had already removed most of the elaborate stage at the Tampa Bay Times Forum, upon which, a few hours earlier, Clint Eastwood had given one of the weirdest political speeches in memory and Mitt Romney had declared, “Now is the time to restore the promise of America.” Most of the red, white, and blue balloons had been picked up. Outside, big diggers were taking down some of the many concrete barricades that the Tampa authorities had erected in expectation of mass protests that failed to materialize.

At the bar of the nearby Sheraton, Jeff Griffin, a Republican small businessman from Georgia, who had driven down to Tampa on a whim, was enthused. Romney had given a very good speech, he said, and Marco Rubio had launched an effective appeal to Hispanic voters. Somebody a couple of seats along the bar suggested that perhaps Eastwood’s performance had overshadowed the other things, and Griffin demurred. Clint “said some powerful stuff,” he insisted. And he cited two lines in particular: “We own this country” and “When somebody doesn’t do the job we gotta let him go.”

Maybe Griffin was right. In the scheme of things, Clint’s comedic turn wasn’t such a big deal—“Aging Hollywood Gunslinger Gets Ornery.” Given his reputation as a straight shooter, in both senses of the term, he might even have helped persuade some undecided voters that it is, indeed, time to give Obama the hook. Taken as a whole, the evening largely accomplished what the Romney campaign wanted it to accomplish—presenting a much more positive picture of the candidate than the Obama campaign and the media has been doing. And much the same can be said of the convention as a whole, which was slickly produced and tightly scripted—apart from Clint.

At the start of the week, I remarked that if the Republicans could avoid any more gaffes, if Hurricane Isaac didn’t do too much damage, and if Romney could give a decent speech that included a few memorable lines and showed a bit of humanity, defying his image as a man made of cardboard, the G.O.P. candidate would probably emerge from Tampa with a bounce. The three days went off pretty much exactly as planned. The storm wasn’t as bad as feared, allowing the Convention to dominate the headlines. All three headline speakers—Ann Romney, Paul Ryan, and the Mittster—gave strong performances that appealed to their target audiences: women (Ann), G.O.P. activists (Ryan), and business-minded independents (Mitt).

Of course, the whole thing was largely a sham. But it was a well-organized sham. Even after attending several G.O.P. conventions since 1998, I find it breathtaking, and a bit unnerving, to watch the party of Ryan, Todd Akin, and Grover Norquist present itself as a moderate force devoted to the causes of deficit reduction, middle-class prosperity, and equal opportunity for all Americans, regardless, of sex, race, or creed. If a foreigner had tuned in between 10 P.M. and 11 P.M., which was all the major networks showed, he or she could be forgiven for supposing that the G.O.P. was the party of Latino Americans, African Americans, and female Americans. Nikki Haley, Condi Rice, Susana Martinez, Artur Davis, Craig Romney speaking Spanish: it looked like one big happy rainbow coalition—until the camera panned to the floor, where the delegates were overwhelmingly white middle-aged Christians.

Even Ryan’s scorching assault on Obama, which the serious media has rightly been excoriating for its factual distortions and omissions, was couched in the language of a disappointed small-town American, an upbeat Reaganite aghast at what he sees around him. The more familiar and less appealing faces of today’s G.O.P.—hard-right billionaire donors, social activists, religious zealots, libertarians, economic crackpots—were virtually absent, as was the last Republican to hold the Presidency: George W. Bush. As far as I saw, the only speakers who mentioned W. by name were Condoleezza Rice and his brother Jeb. (Kudos to them for defying the Orwellian attempt to write him and his Administration out of history.)

Romney’s speech was heavily focussed on family, country, and small business. Some conservatives were disappointed that he didn’t push enough right-wing themes, such as aggressively cutting taxes, slashing government departments, and prosecuting the culture war. But this was perfectly deliberate. Despite the calculated gamble they took in picking Paul Ryan, Romney and his advisers know that elections are won and loss in the center. The one big risk they have taken is hitching themselves to Ryan-style reform of Medicare and Social Security, but this commitment, too, was largely absent from Romney’s speech.

We won’t know until early next week how all this affected the polls. Speaking on Fox News before Thursday night’s speeches, Karl Rove said that he expected the Romney-Ryan ticket to have a two or three point lead by Tuesday or Wednesday. That seems quite plausible. Since Romney unveiled Ryan as his running mate, three weeks ago, the race has been tightening up considerably. On the day of the pick he was trailing Obama by almost five points in the Real Clear Politics poll-of-polls, which averages out the individual surveys. By Friday, Obama’s lead had been reduced to less than a point: 46.4 per cent versus 45.9 per cent.

To be sure, much of this narrowing took place before the convention started, so it can’t be attributed to anything specific that happened in Tampa. Some of it reflects the excitement generated by the Ryan pick, which has enabled the G.O.P. candidates to dominate the headlines for a couple of weeks. Some of it reflects an inevitable tightening as Labor Day approaches and the race gets serious. Both campaigns expected it to happen, and it has. In a story in today’s Tampa Tribune, a Romney operative is quoted as saying, “The race is dead even and has every potential to remain dead even until October,” at which point Romney would move ahead after giving an impressive performance in the debates.

That’s an optimistic prognosis for the G.O.P., but not outrageously so. In a country where the unemployment rate is 8.3 per cent and living standards have dropped sharply since the recession began, in late 2007, the underlying logic of a Romney candidacy has always been fairly compelling: with things going wrong, here is a practical businessman, well-tested in the public sector as well as the private sector, who can use his expertise to turn things around. However, largely due to Romney’s own shortcomings as a politician and some ruthlessly effective attacks upon him by Team Obama, this version of the G.O.P. campaign never really got going, at least until now.

Over the past three days in Tampa, and during the preceding couple of weeks since the Ryan announcement, the Republicans have effectively carried out a product relaunch, seeking to frame their candidate in a more favorable environment. The initial consumer-response surveys are promising, but it’s too early for celebrating. Next week, in Charlotte, the rival firm will be launching a big new advertising campaign for its market-leading product, and it, too, knows how to put on a show.

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read John Cassidy on Mitt Romney’s acceptance speech; Ryan Lizza on Paul Ryan’s five hypocrisies; Kelefa Sanneh on Gary Johnson and Ron Paul; Jane Mayer on Republican women; Hendrik Hertzberg on the “We Built It” slogan; George Packer on foreign policy and the R.N.C. and on Tea Party activists; Amy Davidson on the floor fight, on the Romney love story, on Chris Christie, on Condoleezza Rice, and on shiny things in Tampa; Virginia Cannon on Republican playlists; and John Cassidy on Ann Romney’s and Paul Ryan’s speeches and on Newt Gingrich.

Photograph by Lauren Lancaster.

Raving Clint Spoils Romney’s Big Night

There’s an old adage in Hollywood: never share the screen with dogs or children—you’ll get upstaged. After last night’s bizarro performance by Clint Eastwood, the “surprise guest” at the final night of the Republican National Convention, doddering old men should be added to the list. On a night that was supposed to be all about Mitt Romney and his acceptance speech, the eighty-two-year-old actor and director delivered a rambling speech that had many of the attendees staring around in bewilderment. While it probably won’t make much difference to the election, Eastwood’s routine, which looked as if he’d practiced it for all of five minutes, was the major talking point of the evening.

When Romney finally took the stage, after being introduced by Senator Marco Rubio, he gave a performance that was actually pretty good. It was much more polished than some of his speeches, and also contained an unexpected touch of humanity. On paper, the text he delivered was flat and (lowercase “c”) conservative. Reading through the extracts that the Romney campaign released earlier in the evening, the only memorable line I could find was an outright fib: “I wish President Obama had succeeded because I want America to succeed.” Organized around the general theme that American can do better, much better, most of the rest was standard Republican fare: attacks on Obama’s economic record, paeans to the American tradition, and celebrations of private enterprise.

But the pre-released remarks didn’t include some of the best parts of Romney’s speech, in which he talked about himself, his life, and his family. After months of being pilloried as a heartless private-equity baron, he recalled his early days as an upcoming management consultant and father of five:

Those weren’t the easiest of days—too many long hours and weekends working, five young sons who seemed to have this need to reënact a different world war every night. But if you ask Ann and I what we’d give, to break up just one more fight between the boys, or wake up in the morning and discover a pile of kids asleep in our room. Well, every mom and dad knows the answer to that.

Yes, this was scripted. But it had a ring of authenticity to it, as did Romney’s references to his father and his mother, Lenore Romney, an accomplished woman who ran for the U.S. Senate in 1970 (she lost). “I can still see her as saying in her beautiful voice, ‘Why should women have any less say than men, about the great decisions facing our nation?’ ”

I watched Romney delivering this part of his speech from the convention floor, where, of course, it was warmly received. Returning to the press seats for the second half of the speech, which was more policy orientated, I found that Twitter and the rest of the Web was still abuzz with Clint. It wasn’t that he was dreadful, exactly. In a way, he was refreshing. At an event planned and orchestrated to the second, he hectored an empty chair, supposedly occupied by Obama, for more than ten minutes, interspersing his critical comments about the President’s record with off-color jokes straight out of a retirement home for Borscht Belt comedians. Sample: “What do you want me to tell Romney?” Pause. “He can’t do that to himself.”

For more details of what Eastwood said, I refer you to the post by my colleague Amy Davidson. Vanity Fair’s Todd Purdum, who was sitting next to me, said it was the most bizarre thing he’d ever seen at a political event. Surely the only explanation for how it was allowed to happen can be that Eastwood was too grand a figure to have his lines vetted. Earlier in the evening, on Fox News, Karl Rove averred: “He’s Clint Eastwood. He doesn’t have to say a lot.” Little did Rove know.

The rest of the evening went off pretty much exactly as planned. There were many testimonials to Romney’s integrity, brains, and leadership skills. The character referees included Tom Sternberg, the founder of Staples, which was one of the companies that Bain Capital financed; several Olympic athletes, who praised Romney’s role in organizing the 2002 Winter Olympics; several former colleagues from his time as governor of Massachusetts; and even a former worker at one of the companies that Bain Capital took over, who said, “My life today is better because of Bain Capital. Mitt Romney helped turn around my company. I can’t imagine anyone better prepared to turn around this country.”

From the G.O.P.’s perspective, this was all good stuff. But the major networks, having once again limited their coverage to an hour, didn’t show any of it. All they showed was Eastwood, Marco Rubio, and Romney, who described Bain Capital as “a great American success story.” Much of his time was taken up saying that President Obama didn’t know anything about risk-taking, or creating jobs, or anything else pertaining to the economy.

He took office without the basic qualification that most Americans have and one that was essential to his task. He had almost no experience working in a business. Jobs to him are about government.

I learned the real lessons from how America works from experience.

Here was the Romney that the G.O.P. has been trying to promote all along: the broad-shouldered, self-confident C.E.O. who knows about this stuff, or, at least, looks like he does, and who can take it to Obama. “This President can ask us to be patient,” he said. “This President can tell us it was someone else’s fault. This President can tell us that the next four years he’ll get it right. But this President cannot tell us that you are better off today than when he took office.”

To be sure, when it came to laying out his own economic plan, recently slimmed to five points from fifty-nine, which he claims would create twelve million jobs, Romney didn’t sound any more convincing than he has in the past. As I’ve remarked many times before, one of the great weaknesses of his campaign is that he doesn’t have a convincing jobs plan, or even the semblance of one. Mocking Obama’s 2008 promise to slow the rise of oceans and heal the planet, he said. “My promise is to help you and your family.” But all he had to offer were giveaways to energy companies, free trade, spending cuts, school choice, tax cuts for small businesses, and, yes, you guessed it, repealing Obamacare.

But party acceptance speeches aren’t primarily about detailed policy proposals or engaging in the debate between Keynesian economics and austerity economics. For somebody like Romney, who is challenging an incumbent with pretty low approval ratings, they are about trying to persuade the country that you are an able and honest fellow who wouldn’t be overawed by the Presidency. With the aid of some plausible-sounding character witnesses and some typically slick G.O.P. infomercials, Romney did what he had to do. Unfortunately for him, the only thing that most people will remember about it is the jarring picture of a frail-looking American screen legend, his hair askew, standing and talking in a halting voice to an empty chair.

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read Ryan Lizza on Paul Ryan’s five hypocrisies; Kelefa Sanneh on Gary Johnson and Ron Paul; Jane Mayer on Republican women; Hendrik Hertzberg on the “We Built It” slogan; George Packer on foreign policy and the R.N.C. and on Tea Party activists; Amy Davidson on the floor fight, on the Romney love story, on Chris Christie, on Condoleezza Rice, on Clint Eastwood and on shiny things in Tampa; Virginia Cannon on Republican playlists; and John Cassidy on Ann Romney’s and Paul Ryan’s speeches and on Newt Gingrich.

Photograph by Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images. Illustration by Maximilian Bode.

August 30, 2012

Newt on Newt: The Acceptance Speech That Wasn't

As you are watching Mitt Romney delivering his acceptance speech on Thursday night, or the tape highlights on Friday, spare a thought for the man who just a few months ago thought he would be up there fulfilling his destiny. At lunchtime on Thursday, I spied Newt Gingrich sitting in the restaurant-bar of the Sheraton, just outside the ludicrously large security cordon that surrounds the Tampa Bay Times Forum. When you are a figure of Gingrich’s fame and physical stature, it is hard to go anywhere unnoticed, especially at a Republican Convention, but on this occasion he had almost managed it. There were no security men, no autograph hunters, no reporters harassing him. Just a shirt-sleeved Newt and a couple of pals, tucking in.

After he had finished eating, I followed him up the street to an anonymous tower block, where he was doing a filmed interview with Mike Allen, the crack Politico reporter whose daily Playbook column is required reading in D.C. Thursday night, Newt and his wife, Callista, would have a chance to appear before the convention. But first, there was a less capacious ninth-floor suite that Politico has converted into its convention hub, where about a hundred people were seated. Most of them appeared to be well below the drinking age. And, in fact, they were. To help fill the room, Politico had invited a delegation from the Junior Statesmen of America, a non-partisan group made up of high-school students with an interest in politics and civic affairs.

Newt seemed glad to see a decent crowd. The last time I had seen him in the flesh was back in November, when he flew to New York and courted Donald Trump. On that occasion, his Presidential campaign was still on the up, and he appeared to be a decade younger than his sixty-eight years. He has since turned sixty-nine, and he looks a bit grayer around the gills, which is hardly surprising, given the way his candidacy flamed out. But he’s still the same old Newt. Once the camera lights went on, he talked and talked and talked, mixing sharp political insights with controversial statements, grandiloquent hot air, and even—this being a somewhat chastened world-historic figure—occasional self-criticisms.

Allen started out with a few softballs, asking him what he thought of the Presidential race. Newt compared it to 1980, saying: “Reagan had Carter, Romney has Obama. The parallels are eery.” Ultimately, he said, Obama’s record on the economy and other issues would do him him. “The American people are tough consumers. They don’t go back to a store which gives them bad products.” He referred to Joe Biden as “idiotic,” praised Paul Ryan’s speech, and said that Romney’s choice of him as his running mate was “a stroke of genius,” adding, “he set up the clearest choice since the McKinley-Brian contest of 1896.”

Detouring, at Allen’s request, to the Todd Akin scandal, Gingrich defended the embattled Missouri Republican, whom he clearly sees as some sort of kindred spirit. Akin made a mistake and said something stupid, Gingrich said, but he had a long record in the conservative movement, and he didn’t deserve the avalanche of criticism he had received from establishment Republicans. “This is the guy who won the primary. Who are the money guys to call up and say, ‘You’ve got to get out’?” Sensing a possible newsbreak—Gingrich’s words made him the first senior Republican to defend Akin—Allen pressed him on the congressman’s controversial statements about abortion. Gingrich repeated that what Akin said was dumb. Still, he added, “having over the years made a fool of myself, I just bit my tongue a bit.” He went on, “It’s hard. You go out in public.”

Gingrich, of course, has been out there for almost forty years. Asked how his acceptance speech would have differed from Romney’s had he won the nomination, he said their “top lines” would be surprisingly similar: get rid of Barack Obama, liberate the economy from an overweening government, and the United States “will recover at a rate that will shock the world.” Of course, he added, “I’m more of a rhetorical risk taker than he is.” Talking about a lunar colony in the crucial G.O.P. debate in Jacksonville, when he had just defeated Romney in South Carolina, “wasn’t the cleverest thing I’ve done,” he allowed, a wry smile crossing his face.

If he harbors any bitterness towards the man who beat him, he hid them well, describing Romney as “a very solid, smart guy,” who beat him fair and square in the two crucial G.O.P. debates. And, once again, he praised Romney for picking Paul, “the most controversial young Republican,” saying it was “strategically a very high risk choice,” but a “brilliant” one nonetheless.

With Romney as the Presidential candidate and Ryan as his running mate, Gingrich has been forced to give up not just his Presidential ambitions but his role as the G.O.P. philosopher-in-chief. Allen asked him if he felt eclipsed by Ryan. Gingrich said that he didn’t. “The wonderful thing about ideas is you put two of them together and you get twenty-five,” he said. “He and I aren’t competing.” Politely but firmly, Allen said, “You don’t feel pushed aside?” Gingrich, one of whose many enthusiasms is football, replied, “I feel like John Madden. I’m not the quarterback; I’m not the head coach running up and down the sidelines. I’m a commentator. But Madden had another twenty-five or thirty years as a commentator. I don’t mind spending the next fifteen years educating a generation… I think that would be fun.”

The junior statesmen and stateswomen of American looked on politely. A couple of them asked well-informed questions about local races, which Gingrich answered in an equally well-informed manner. Allen said that their time was almost up, but Gingrich wasn’t in any rush to finish. All he had on his agenda for later on was a convention speech, one scheduled for well before prime time, in which he was to discuss the historical importance of Ronald Reagan. For now, he talked about the G.O.P.’s need to reach out to hispanics and other minorities, his deep passion for zoos, and a recent birthday trip to a military base that he had arranged for one of his granddaughters. One of the young questioners asked him about the upcoming Presidential debates, citing his famous offer to square up against President Obama in seven three-hour Lincoln-Douglas debates.

The old warhorse’s eyes lit up. He couldn’t resist himself. How many of the people in the room would like to see him debate Barack Obama, he asked. A lot of hands went up. Gingrich said that he had an idea for Obama. Next year, “when he is unemployed,” the two of them should organize a nationwide debating tour in which they would go head-to-head in the manner of Lincoln and Douglas, with the proceeds going to the charities of their choice: “The zoos will do great.”

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read Ryan Lizza on Paul Ryan’s five hypocrisies; Kelefa Sanneh on Gary Johnson and Ron Paul; Jane Mayer on Republican women; Hendrik Hertzberg on the “We Built It” slogan; George Packer on foreign policy and the R.N.C. and on Tea Party activists; Amy Davidson on the floor fight, on the Romney love story, on Chris Christie, and on shiny things in Tampa; Virginia Cannon on Repulican playlists; and John Cassidy on Ann Romney’s and Paul Ryan’s speeches.

Illustration by Tom Bachtell.

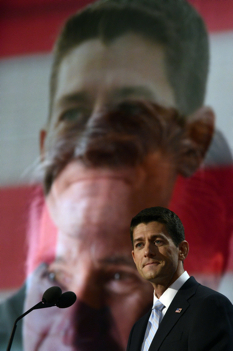

Cheesehead Delivers Red Meat

The Wisconsin boy wonder started slowly. Declaring that he was honored to accept “the calling of my generation,” he sounded a bit stiff, as if he were nervous, or struggling with the teleprompter. Whether because of his natural coloring, or because he hadn’t shaved since the morning, he was sporting a five-o-clock shadow, which, for some old timers, may have evoked memories of Richard Nixon. Not that the rest of his appearance was anything like Tricky Dick’s. With his dark suit, white shirt, cropped black hair, and pained expression, he looked more like a character out of “Reservoir Dogs.”

Things got better. Once he stopped trying to be Vice-Presidential and started laying into Obama and the Democrats, as he usually does, he was fine. “They’ve run out of ideas: their moment came and went,” he said about three minutes in. “With all their attack ads, the President is just throwing away money—and he’s pretty experienced at that.” It wasn’t the greatest line, but the four thousand delegates laughed and cheered loudly, something they’d been waiting to do for quite a while. It’s all very well watching Ann Romney explain what a lovable fellow her husband his, and applauding Condi Rice for being a member of the G.O.P., but what the average delegate really wanted to do was boo and hiss at Obama, and see somebody put him down. Ryan, as his forty-minute speech progressed, did this with brio, amply demonstrating why Romney had picked him.

Sometimes portrayed as a visionary or a deficit hawk, he is actually a well-informed and articulate Republican attack dog, who—and this is important in a party that has struggled to lay a blow on the President despite a dismal economy—doesn’t seem overawed by Obama. Once he got going, he mocked the President’s communication skills, saying there had been more than enough talking in the past four years, and “what is needed is leadership in the White House”—a quip that earned him a thirty-second ovation. He mocked the President’s pledge to bring down the national debt, saying that he had “added more debt than any one before him.” And in what was perhaps his best line, he mocked the high hopes that Obama raised in 2008, saying: “College graduates shouldn’t have to live with their parents, staring up at fading Obama posters and wondering when they can get going with their lives.”

Like many effective politicians, Ryan is more than willing to stretch the facts to the point of spreading deliberate misinformation. He described the 2009 stimulus act, most of which was spent on tax cuts and transfer payments to the unemployed and the cash-strapped states, as “political patronage, corporate welfare, and cronyism at their worst.” Ignoring the White House’s overtures to Speaker John Boehner last summer about a possible budget deal—a deal he helped to sink—he accused Obama of doing “nothing” to tackle the national debt, or the entitlements crisis. And glossing over his own budget, which does largely the same thing, he accused the Obama administration of stripping more than seven hundred billion dollars from Medicare to fund its health-care reform bill. “An obligation [to the elderly] is being sacrificed to pay for an entitlement program we didn’t even ask for,” Ryan declared. “The greatest threat to Medicare is Obamacare, and we are going to stop it.”

You had to admire his gall, or his recklessness. Earlier in the day, there had been speculation that he wouldn’t mention Medicare at all—an option many G.O.P. members of Congress would have welcomed. Instead, he put the issue of what to do about the health-care system for retirees—he wants to convert it to a voucher program—front and center, saying: “We need this debate. We want this debate. We will win this debate.”

We shall see about that. Somewhere up north, Chuck Schumer and David Axelrod will have been cheering at the prospect of Medicare displacing jobs in the fall campaign. But the Romney campaign must have also made that calculation, several weeks ago. When the Mittster selected Paul, he knew he came with baggage. But he evidently reckoned that the upsides—his youth, his energy, his eloquence, his popularity with the party activists—more than made up for it.

On the basis of Wednesday night’s speech, Romney probably made the right choice. About an hour before Ryan spoke, the two losing finalists in the veepstakes—Rob Portman and Tim Pawlenty—gave two of the least impressive speeches I can remember at a convention. Portman was so dull that, by the end of his speech, most of the delegates where I was standing were deep in conversation. Pawlenty told a series of lame jokes, including one about a tattoo that doesn’t bear repeating on a family website—not because it was offensive, but because it was so embarrassingly bad.

The two of them—Portman and Pawlenty—were so poor I almost suspected that the Romney campaign had spiked their drinks to make Ryan look good by comparison. Whatever you think of Romney, in passing over Ryan’s rivals on the Veep shortlist, he did us all a big favor. Nobody, not even those of us who are paid to do it, could have listened to two months of Portman or Pawlenty.

Whether Romney did himself a favor is much less clear. To the extent that he needed to fire up the G.O.P. base, it was an inspired choice. Having spent his entire career in Republican politics, Ryan knows how to talk the party language, which signifiers to use. On this occasion, he avoided mentioning Ayn Rand or Friedrich Hayek, two of the patron saints of economic conservatives, by name, but he did evoke the memory of Jack Kemp, one of his early mentors, and he dropped in one distinctly Randian line, saying young Americans deserved better than “a dull adventureless journey from one entitlement to the next—a government-planned life.”

As Ryan finished up his speech, by saying “let’s get this done,” the hooting and hollering almost drowned out his words. Because of all the interruptions he had run a few minutes past the eleven-o-clock cutoff for prime-time coverage, but the network execs won’t have minded too much. In his right-wing fervor, his harsh rhetoric, and his thinly disguised contempt for the President, Ryan embodies the modern G.O.P.—warts and all. That makes for a good convention speech, good television, and a good story. But it doesn’t necessarily help win a Presidential election.

Photograph: Brendan Smialowski/AFP

For more of The New Yorker’s convention coverage, visit The Political Scene. You can also read Kelefa Sanneh on Gary Johnson and Ron Paul, Jane Mayer on Republican women, Hendrik Hertzberg on the “We Built It” slogan, George Packer on foreign policy and the R.N.C., Amy Davidson on the floor fight, on the Romney love story, on Chris Christie, and John Cassidy on Ann Romney’s speech.

August 29, 2012

The G.O.P. Finally Falls for Romney—Ann Romney

Can anybody here play this game? At about ten o’clock last night, I was beginning to wonder. After being delayed a day, the G.O.P. convention had finally gotten started, but its first few hours had been strangely flat. The delegates—Ron Paul’s excepted—had been quiet; the speeches had been disappointing; and even the reading of the roll call, which is usually fun, had failed to produce much excitement, The biggest cheer went to Paul’s strong showing in Iowa. When New Jersey cast its votes for Romney, it put him over the top, making him the official G.O.P. candidate. The cheering and waving of “Mitt” signs was strangely stilted.

The night session brought an awkward appearance by Rick Santorum (remember him?); a self-congratulatory speech from Scott Walker, the Wisconsin union-basher; and a surprisingly uninspiring performance from Nikki Haley, the wunderkind Indian-American who is governor of South Carolina. At this stage, about the only thing you could say for the organizers was that they had found three of the only non-white faces in the building and put them on stage in rapid succession: Artur Davis, the African-American former congressman from Alabama who changed parties; Haley; and Lucé Vela, the first lady of Puerto Rico. Who says the G.O.P. doesn’t care about courting the minority vote?

Then Ann Romney took the stage, a vision in red. Earlier in the day, on the flight down to Tampa, she had told the that pool reporters she was nervous about her speech, because she had never used a teleprompter. “I don’t like it,” she said. “It’s hard. We’ll see how I do.” It was the old head fake. Anybody who saw Mrs. Romney during the primaries knows that she loves talking about her husband, and she’s very good at it. To be sure, there was a possibility she would freeze on the big stage, but she quickly dispelled that idea, informing the crowd that Hurricane Isaac had just made landfall, and asking them to consider for a moment all those Americans who stood in its path.

Perhaps a speechwriter had inserted the line, but she delivered it with the timing and gentle touch of a pro. And she followed it up by pirouetting to the theme that Romney’s flaks had leaked to the press a few hours earlier, saying: “I want to talk to you, from my heart, about our hearts.”

“We love you, Ann,” a male voice shouted from the floor.

“We love you, Ann,” repeated someone else.

She was only getting going. She wanted to talk about the one thing that unites us all, she went on. “Tonight, I want to talk to you about love. I want to talk to you about the deep and abiding love I have for this man.” But first, she regaled us with concern for the working folk she’d met in the months of campaigning with Mitt. No, she wasn’t talking about Shelly Adelson, the Koch Brothers, or Paul Singer, though all of them are reported to be hard workers. She was talking about parents who lay awake at night wondering how they will pay the rent; fathers working extra hours so their kids can play sports at school; working mothers who want to spend more time with their kids but can’t afford to do it. “I’ve seen and heard stories of how hard it is to get ahead now. I’ve heard your voices.”

All across America, liberals and feminists were recoiling from their screens. Some may have actually retched. I’d bet a few shouted, “What about dressage?” But here in the Tampa Bay Times Forum, home to the N.H.L.’s Tampa Bay Lightning, a respectful silence was falling. The G.O.P. was finally falling in love with Romney—Ann Romney. By the time she got back to talking up her man, the real business of the night, she was positively beaming, her streaked blond hair glistening in the light, which also illuminated her perfect teeth and rouged lips. For a sixty-three-year-old, she looked great. For a sixty-three-year-old multiple-sclerosis victim and cancer survivor—yes, she managed to sneak in those details—she looked fantastic.

Now it was onto Detroit in the mid-sixties, and a gangly, handsome youth whom she met at a high-school dance. “He was tall, laughed a lot. He was nervous. Girls like that. It shows they’re a little intimidated. More than anything, he made me laugh.” People told them they were too young to wed, she recalled. “We just didn’t care. We got married and moved into a basement apartment,” where we “ate a lot of pasta and tuna fish,” using folded door for a desk and an ironing board for a kitchen table.

I don’t know who wrote this stuff, or whether the details about the door and the ironing board are true, but it was good. Simple, direct, touching—everything Mitt isn’t.

After a brief recitation of her husband’s business career, in which she managed to avoid saying the words “Bain Capital,” and a detour into his good works for his church and neighbors, which he doesn’t talk about because “he sees it as a privilege, not a political talking point,” it was onto the payoff. Nobody would work harder for America, or care more about America than her hubby. A serious expression replaced the winning smile. She raised her right hand and wagged her index finger in a manner that reminded me of Mrs. Thatcher.

“I can only stand here as a wife, a mother, and a grandmother, and make you this solemn commitment: this man will not fail you.” Once again, she raised her finger in the air for emphasis. “This is our future,” she went on. “These are our children and grandchildren. You can trust Mitt. He will take us to a better place just as he took me home safely from that dance.”

Amid much shouting and stamping of feet, and to the strains of “My Girl,” the Mittster himself briefly appeared to kiss and congratulate his better half. To what must have been relief in the White House and in Chicago, he didn’t offer to pull out of the race and place his delegates behind her. He didn’t say anything. In less than a minute, the two of them—the pretty girl and her suitor, still together forty-seven years on—were gone from stage.

After all that, Chris Christie came on and delivered what had been billed as a keynote speech but turned out to be a late-night rah-rah session for the G.O.P. rank and file. He bashed the teachers’ unions, medical bureaucrats, and, of course, Barack Obama. It was the speech of a blowhard rather than a visionary, but the audience inside the hall liked it. I doubt it went over as well on national television. That, didn’t matter very much though. The night belonged to Ann Romney, and she aced it.

Somewhere in the netherworld, Michael Deaver and Lee Atwater were smiling. From a bit closer—New York, probably—Roger Ailes was also looking on approvingly. The legendary Republican media operation, for years feared by Democrats everywhere, had put on an excellent show. It was schmaltzy, it was cynical, and some of it (perhaps most of it) was tendentious. But it was effective.

Photograph by Mladen Antonov/AFP/GettyImages.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers