John Cassidy's Blog, page 116

May 18, 2011

LinkedIn's I.P.O.: Party Like It's 1999?

Newt Gingrich is busy self-destructing; Osama bin Laden is no more; Morgan Stanley is rolling out a new Internet I.P.O., which investors are fighting to get their hands on. Am I the only one feeling a bit like I've fallen asleep for twelve years and awoken in May 1999?

Shares in LinkedIn, a networking site for yuppies, will be priced this evening and start trading tomorrow morning. The issue price has already been raised from $32-$35 to $42-45—a big jump—and it wouldn't be a great surprise to see the stock trading at $55 or $60 by tomorrow evening. If the stock does pop and then holds up, we can expect even bigger I.P.O.s in the coming months from the likes of Facebook, Groupon, and Zynga.

Having written an entire book about the original dot-com bubble, I'm trying to resist the urge to say this is a 2.0 version of the same. For several years now, the I.P.O. market has been effectively closed to U.S. Internet companies, and the only cash-out option for entrepreneurs and venture capitalists has been selling to a big public company, such as Google or Microsoft. This didn't make much sense. The likes of LinkedIn and Groupon aren't Webvan and Pets.com. They are real companies, with real competitive advantages, and they operate in a sector of the economy where the United States has a big lead. It is hardly surprising that individual and institutional investors would want to own some of these companies. The shocking thing is that the I.P.O. market has remained closed for so long. But after the excesses of 1998-2000, this was probably inevitable.

Still, the parallels with the late nineteen-nineties are hard to avoid, beginning with the valuation being placed on the company (roughly $4.5 billion at the issue price) and the involvement of Morgan Stanley and Merrill Lynch, which is also acting as an underwriter. (These days, the firm is known as BofA Merrill Lynch.) To be sure, the legendary Internet stock analysts Mary Meeker and Henry Blodget are no longer playing a role, but wait—that isn't quite true. Having been barred from the securities industry, Blodget is now a media entrepreneur. (Meeker is a venture capitalist.) And on Blodget's lively Business Insider site, I just read an article by an anonymous money manager entitled: "Here are 10 Reasons Why I Am Going To Load The Boat On LinkedIn's IPO."

Actually, the piece makes some sound points—even if it was written by somebody who has been promised an allocation of stock and is planning to flip it. With more than a hundred million registered users, LinkedIn is less a social network than a jobs and recruitment network. According to its prospectus, almost four thousand companies used the site in 2010, paying an average annual fee that the Business Insider article put at $8,000. People looking for a job pay from twenty to fifty dollars a month to have their profile listed and matched with potential hirers. As the prospectus repeats numerous times, this is a business where network effects are potentially very powerful. The more recruiters use the site, the more useful it will become to job-seekers, and vice versa.

From an economic perspective, it is a network externalities story and a credible one. But is LinkedIn worth five billion? (That would be approximately its capitalization at a stock

price of $50.) Last year, its revenues doubled to $243 million. Assuming revenues double again in 2011, a five-billion-dollar valuation would amount to twenty times revenues, which seems more than a tad high. Salesforce.com, the cloud-computing firm that many consider a bubble stock, trades at ten times revenues. Google trades at five-and-a-half times its sales. Yes, these are more mature companies than LinkedIn is, but it isn't exactly a stripling either. The site launched in early 2003, and, by some metrics, its growth rate is no longer accelerating.

As for earnings, unlike many of the original dotcoms, LinkedIn does have some: $15.4 million in 2010 and $2.08 million in the first quarter of this year. But the firm says it isn't expecting to be profitable in the next couple of years, when it plans on ramping up its investments. Dividends? Don't be silly. The prospectus says none will be issued for the foreseeable future.

In fact, you can be pretty sure that LinkedIn will be a public company where the voice of ordinary shareholders will be largely ignored. Mimicking Google and other technology companies, it is setting up a dual-stock structure that reserves most of the voting rights for insiders, including Reid Hoffman, the firm's founder, and various venture-capital investors. As the V.C.s cash out, Hoffman, who currently owns twenty per cent of the company, could well end up with sole voting control—a fact spotted by the Financial Times' Richard Waters.

If that's the sort of company you want in your retirement portfolio, go ahead and contact your broker about buying some LinkedIn stock. But call early: he's probably busy.

Photograph by Nan Palmero.

May 3, 2011

After Bin Laden: Let's Stop Playing His Game

While my colleagues have been commenting expertly on many aspects of the bin Laden story, I have been thinking about history: personal history, political history, military history. Like many New Yorkers, I find it a bit hard to separate one from the other.

Driving to J.F.K. on Sunday evening to pick up my wife, who was flying back from Europe, I was struck by the dry, brisk air and blue cloudless sky. My mind went back, as it often does in such conditions, to the morning of September 11, 2001, when, on Duane and Greenwich, a reporter's notebook in hand, I watched the South Tower tumble into a great dust cloud that quickly enveloped the corner on which I was standing. (I filled up a Styrofoam cup with some of the detritus: it is still in my desk drawer.)

Such ghoulish thoughts were but fleeting: before I got to the airport, I had put them out of my mind completely. After arriving home we retired early and missed the announcement from the White House. Bin Laden's entry onto the world historical stage, I saw close up; the dramatic news of his exit, I slept through.

Perhaps that was all to the good. Too much exposure to history-in-the-making can lead to trouble. Look at what it did to George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, and their neocon advisers, who decided that the appropriate response to an opportunistic attack by a geographically scattered group of religious fanatics was to launch a "War on Terror," and then to invade Iraq, the biggest secular country in the Middle East. Eight years after the beginning of that immensely costly diversion it was old-fashioned police (intelligence) work and a small-scale special-forces operation that produced the desired result.

Mulling all this over, I was reminded of the warnings issued in the aftermath of 9/11 by Sir Michael Howard, the British military historian. An admirer of the United States (he lived and taught here for several years) and no peacenik (as a young man, he served in the Coldstream Guards), Howard said that adopting war terminology in response to the criminal threat posed by Al Qaeda could lead to a century-long conflict. The gravest threat to world peace—and to America's long-term security interests—Howard argued, was the possibility of the wounded superpower lashing out indiscriminately.

Of course, this is precisely what bin Laden had in mind by encouraging his followers to bring their twisted and maniacal cause to the streets of New York and Washington. In his writings on Al Qaeda, Lawrence Wright has quoted al-Zawahari saying this almost exactly: 9/11 was a spectacular provocation, designed to draw the United States and its allies into open warfare. Bush and Tony Blair followed bin Laden's script as if reading from a screenplay.

Which is why, in historical terms, the dissident Saudi's violent campaign, even though it engendered the breakup of his organization and, ultimately, his own violent death, was a certain kind of success. The overreaction by the United States and its allies to 9/11 implanted in the minds of many alienated Muslim youths (and a good many not-so-youthful devotees) the fateful notion that the world, as represented by the United States and other Western powers, was their implacable enemy.

The killing of Bin Laden won't change this mindset; it could conceivably strengthen it. From the perspective of most peace-loving Westerners, a despicable human being has been eliminated and justice has been served. To many radicalized Muslims, the Navy SEALs have created another martyr. It is to be fervently hoped that that bin Laden's death will dishearten his followers and further disrupt what remains of Al Qaeda. Still, it is depressingly likely that some day soon a group of committed jihadis will seek to avenge his death with more bloodshed.

As Howard predicted, the "War on Terror" could well go on and on—an endless cycle of action and reaction, which some commentators almost seem to revel in. "(T)he fight against al-Qaeda is not over, and it is far from our only enemy," an editorial in the National Review declared on Monday. "September 11 thrust the United States into a generation-long conflict: It is our Thirty Years', perhaps our Hundred Years' War."

What a nightmarish prospect. Now that bin Laden is gone, surely it is time to challenge the logic of eternal conflict that he expounded—to quit playing the game he wanted us to play.

A good place to begin might be with the speech that Howard gave in London in October 2001, when construction crews were still clearing Ground Zero of human remains. "To declare war on terrorists or, even more illiterately, on terrorism, is at once to accord terrorists a status and dignity that they seek and that they do not deserve," Howard said. The U.S. Air Force was busy bombarding Afghanistan, a military campaign that Howard likened to "trying to eradicate cancer cells with a blow torch." Even more disastrous, he went on, would be an extension of the U.S. military campaign "through other rogue states, beginning with Iraq, to eradicate terrorism for good and all. I can think of no policy more likely, not only to indefinitely prolong the war, but to ensure that we can never win it."

At this remove, who can say for sure that Howard was in error? American troops, by the tens of thousand, are still on the ground in Iraq and Afghanistan. The covert U.S. military footprint grows ever larger. As of the latest counting, the Pentagon has launched missile attacks against targets in four other Muslim countries: Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, and Libya. (The latter strike wasn't officially part of the War on Terror.) Despite it all, the violent threat of radical Islam remains—not least from jihadis who were homegrown in the United States, Britain, Holland, and other Western countries.

As of yet, I haven't even mentioned economics. In 2001, the defense budget stood at about $300 billion: today it is more than $700 billion. Even allowing for inflation, this represents roughly a doubling in outlays. Twenty years after the demise of the Soviet Union, the United States is spending more money on soldiers and armaments than the rest of the world combined. How long can this go on? For a debt-ridden colossus that depends on Beijing and other foreign capitals for day-to-day funding, it smacks of the imperial overstretch that another British historian, Paul Kennedy of Yale, warned about way back in 1987—before virtually anybody in the West had heard of bin Laden.

So, all credit to President Obama for authorizing a successful mission and to the Navy SEALs for carrying it out. But where do we go from here? In May 2011, we can't rerun history. We can try and alter its future course. Bin Laden's death and the looming anniversary of 9/11 provide a fitting occasion to embark on such an effort.

(Postscript: Reading Ryan Lizza's latest post, it seems that some people in the administration, including the President, are thinking along broadly similar lines to these. If Ryan's right—and he usually is—that's encouraging news.)

April 27, 2011

All Together Now: We Support a Strong Dollar

One of the drawbacks of being Secretary of the Treasury or Chairman of the Federal Reserve is that, from time to time, you are obliged to tell fibs—and pretty big ones at that. This is especially true when it comes to a matter close to the heart of every American citizen and every foreign investor: the value of the dollar.

And so we have the sorry spectacle of Timothy Geithner and Benjamin Bernanke, within a day of each other, each insisting on something that patently isn't true.

Here's Geithner, speaking to the Council on Foreign Relations, on Tuesday: "Our policy has been and will always be, as long as at least I'm in this job, that a strong dollar is in our interest as a country. We will never embrace a strategy of trying to weaken our currency to try to gain economic advantage."

And here's Bernanke, talking to reporters at his much ballyhooed inaugural press conference on Wednesday: "The Federal Reserve believes that a strong and stable dollar is both in American interests and in the interest of the global economy."

On the face of it, these statements amount to a watertight commitment to maintaining the value of the greenback from the top two economic policymakers in the country. Why, then, did currency traders knock another half a cent or so off the value of the dollar against the Euro while Bernanke was talking?

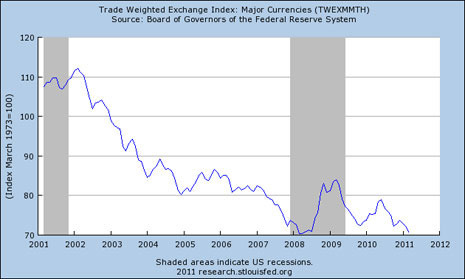

The answer can be found in this chart, which shows the value of the dollar against other major currencies, such as the Euro and the Yen.

What the chart shows is that, over the past ten years, under Democratic and Republican Administrations, the Fed and the Treasury Department have presided over a thirty-six per cent decline in the value of the dollar. Since November 2008, when the Fed embarked on its now-suspended policy of quantitative easing—pumping money into the economy by purchasing Treasury bonds and other securities—the dollar has lost more than a sixth of its value. In fact, the chart understates the fall a bit, because it doesn't include the most recent figures, which show the dollar index dropping under seventy. (On Wednesday, it closed at 69.2, close to its all-time low.)

Now, Geithner and Bernanke can say until they are blue in the face that they are committed to a strong dollar. But practically everybody knows that one of the goals of quantitative easing was to bring down the value of U.S. currency, at least temporarily, in order to boost exports and economic growth. (When the dollar falls, American exports become cheaper for foreigners to buy.) We know it; the Europeans know it; so do the Japanese; and so the Chinese, who own some $3.5 trillion worth of dollar-denominated bonds and stand to suffer big losses from any further dollar weakness. Evidently, however, it is a truth that cannot be stated—even by a Fed chairman committed to "transparency."

Actually, if you parsed Bernanke's statements, you would see he was a bit uncomfortable telling what the British call "porkies." In defending the Fed's policies, he said: "In our view, if we do what's needed to pursue our dual mandate for price stability, maximum employment, that will also generate fundamentals that will help the dollar in the medium term."

Note the phrase "medium term." What Bernanke is saying is that if the Fed eventually succeeds in getting the U.S. economy back into a position where the recovery is no longer dependent on stimulants provided by the government, foreign capital will flood into the United States and the value of the dollar will recover from the damage that quantitative easing inflicted upon it. Perhaps it will, but currency traders aren't looking that far ahead. They are looking at the chart and at the Fed's renewed commitment to maintaining near-zero interest rates, both of which suggest the U.S currency is a one-way bet. (Down!) Until the Fed moves decisively to raise interest rates, anything Bernanke (or Geithner) says about the dollar is merely "cheap talk," which the markets will discount, as well they should.

(By the way, apart from following the party line on the dollar—which was only to be expected—Bernanke did a good job, I thought. He came across as knowledgeable, reasonable, modest, and well meaning, which is a pretty good description of his character. He didn't make any errors or say anything inadvertently that could have spooked the markets. And, speaking over the head of the reporters, he delivered a message that he wanted the American public to hear: the Fed, in difficult circumstances, is doing all it can to promote economic growth and job creation, whilst keeping one eye on inflation. To the extent that the Fed is now under attack from right-wing know-nothings who regard it as the font of all economic evil, this is all to the good. Will the Fed's new policy of openness ultimately make much difference in policy terms? I doubt it.)

Graph via the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

April 18, 2011

Pulitzer Judges Honor Financial Writers

The subprime crisis of 2007-2008 may have receded into recent memory, but the Pulitzer Prize committee acknowledged on Monday that economic and financial issues continue to dominate the news. My congratulations to Jesse Eisinger and Jake Bernstein of ProPublica, who were awarded the Pulitzer for National Reporting; and to David Leonhardt, the economics columnist of the New York Times, who was honored for commentary.

The award to Eisinger and Weinstein is particularly notable because of where their cited work, a series of stories entitled "The Wall Street Money Machine," appeared: online only. This is the first time a piece of reporting that didn't make a print edition has received a Pulitzer, and it showed how the old classifications are fast fading away. Until a couple of years ago, Eisinger was a fellow columnist of mine at Portfolio, a glossy magazine, where he penned hard-hitting pieces on Wall Street. Today, he writes equally trenchant articles for ProPublica. Some of them are reprinted in the Times's Dealbook pages, and some aren't.

Evidently, the Pulitzer committee is still focussed on major newspapers—six of the twelve prizes went to the Times (two), the Los Angeles Times (two), the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. The recognition that good work is also being done online was overdue. If serious journalism is to have any future, online reporters and editors, who probably already make up the majority of the profession, need encouragement. Is it too much to hope that one of these days a commercial website will match the output of ProPublica, a not-for-profit news organization that was founded by Paul Steiger, a former managing editor of the Wall Street Journal, and funded by the Sandler Foundation?

David Leonhardt's prize was also welcome: his columns are well-researched and often newsworthy. Hats off to the editors of the Times for starting many of them on page one. All economics writers should be grateful to the Times brass for overturning the old convention that economic analysis should be confined to the business pages, where it can nestle with corporate earnings releases and stock market reports. Economics is much too important for that!

April 13, 2011

Budget Battles: Advantage Obama

Late last year, when President Obama overhauled his economic team, some people complained that the departure of Larry Summers and Christina Romer left the White House short of first-rate economists. That may have been true, but what the White House lost in intellectual sparkle it more than made up for in Washington know-how. With Gene Sperling as head of the National Economic Council and Jack Lew as budget director, it boasts two veterans of the Clinton-era budget war—two men who know how to outmaneuver right-wing Republicans.

In the past few months, Sperling and Lew have been playing from the nineteen-nineties playbook. Initially, they produced a budget for 2012 that didn't do very much at all about long-term deficits, and was instantly proclaimed dead on arrival. Budget hawks cried foul. But the White House was playing a long game, and its budget proposal was merely an opening gambit. Then came Congressman Paul Ryan with his radical "roadmap" to budget balance over the next ten years, which featured slashing reductions in domestic spending, more big tax cuts for the rich, and the conversion of Medicare to a voucher program. I irked some readers by saying that Ryan deserved credit for at least making a specific proposal, but I still believe liberals everywhere should be grateful. By spelling out what the Republicans would do to Medicare and Medicaid, he may well have deprived his party of the White House for the foreseeable future.

If you want to know why Ryan's "budget-cutting" plan makes no financial sense, the Financial Times' Martin Wolf spells it out very clearly in his latest column, which is based on an analysis by the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office analysis. If you want to know why Ryan's plan is political poison, look at Ezra Klein's blog, where he cites a recent opinion poll showing that a plurality of Republicans—yes Republicans—think the best option for Medicare is to not cut it at all. To say the very least, Ryan presented President Obama with a big opportunity to occupy the center ground. And despite the jibes about him being a covert socialist, this is clearly the ground on which the President feels most comfortable.

And so to today's budget speech, in which Obama presented his own eminently centrist plan to reduce the deficit without privatizing Medicare, without slashing domestic spending to the point where many government programs won't be able to operate, and without introducing any big tax increases. I wouldn't sweat the individual numbers that Obama presented, such as his claim that his proposals would cut the budget deficit by four trillion dollars over twelve years. Forecasting the budget deficit next year is a challenge. Forecasting the deficit three years out is extremely difficult. Ten-year budget projections are largely meaningless.

What is important is the big picture. Where Ryan proposes radical changes to taxes and spending that would alter the social contract between government and governed, President Obama is arguing that we can trim our way to fiscal sustainability. Some cuts here, some tax breaks eliminated there, and, lo and behold, the deficit will be down to two per cent of G.D.P.

To be fair, the President isn't saying it will be easy. If by 2014 Congress can't come up with enough cuts to stabilize the debt-to-G.D.P. ratio, he is calling for a "debt failsafe" trigger that would involve spending reductions in all programs except Social Security, Medicaid, and low-income programs. To slow the growth of entitlement spending, he is proposing to beef up the Independent Payment Advisory Board, which the health-care reform act created, and setting it at a target of keeping Medicare growth to the rate of G.D.P. growth plus half a per cent. Even the Pentagon, which has been largely exempted from budget pressures since 9/11, would have to find some (overly modest) cuts. But compared to what Ryan is proposing, these are all relatively minor changes.

Is the plan credible? Without seeing the details, it is hard to say. In the fact-sheet it circulated today, the White House avoided saying which tax loopholes it is in favor of eliminating—the mortgage interest deduction?—and it also failed to provide any projections about, say, the level of federal spending and debt as a percentage of G.D.P. in 2020. That vagueness was certainly deliberate. At this juncture, the White House still doesn't want to reveal all of its hand. Rather than placating the budget hawks with a definitive and fully worked out set of proposals, the Administration is betting that the bond market will give it more time—time in which the American people can learn more about the specifics of Ryan's proposals, and get even less enthusiastic about them.

This game still has a long way to run. But if I were a betting man, and occasionally I am, I would wager on Sperling and Lew coming out on top rather than the congressman from Wisconsin.

Photograph: AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais.

April 12, 2011

Inside George Soros's "Monstrous Monkey House"

Snow-capped peaks; nightcaps with Larry Summers; discussions of complexity theory over breakfast; Tennyson quotations from Gordon Brown at lunch. No it's not Davos—it's Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, where over the weekend the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET), which George Soros set up in the wake of the financial crisis, held its second annual conference. Last year's inaugural get-together was held at King's College, Cambridge, the home of Keynes. This year's location also had a strong link to J.M.K. It was the grand old Mount Washington Hotel, which in the summer of 1944 played host to a famous international conference about the post-war monetary system.

Soros launched INET in 2009 with the intention of fostering fresh ways of thinking to replace an economic orthodoxy that manifestly had failed. Two years on, it's not clear how far he's succeeding in that enterprise, but Rob Johnson, a former Capitol Hill staffer and employee of Soros Fund Management, who heads up INET, has certainly put its annual meeting on the map. This year's conference attracted more than two hundred economists, policy makers, and journalists from around the world. The subjects covered ranged from "Too Big to Fail" to the European debt crisis to "New New Trade Theory."

While the conference lacked some thematic unity, the speakers delivered a range of interesting insights. Soros himself kicked things off. In a panel session on Friday afternoon, he said he found the current economic situation "much more baffling and less predictable than … at the height of the crisis." Whilst policymakers had succeeded in averting a second Great Depression, they were now at "the delicate stage" of withdrawing some of the emergency policy measures they have been relying on. Meanwhile, on issues such as Europe, financial regulation, and climate change, it wasn't clear whether the political will was there to introduce the necessary reforms. There are a "number of unsustainable situations that nonetheless continue," Soros concluded. "Politics has become the most important factor in determining the outcome."

Larry Summers wasn't an obvious choice to speak at a conference devoted to jettisoning old orthodoxies, some of which he championed. But in conversation with the Financial Times' Martin Wolff he acquitted himself pretty well. Asked whether economics had failed, he said, "I think economics knows a fair amount. It has forgotten a fair amount. It has been distracted by a lot of things." Summers criticized the macroeconomic orthodoxy that, in the past twenty years, has dominated thinking in universities and central banks, noting that when the crisis came it provided little guidance to policy makers. "The vast edifice—in both its New Keynesian and New Classical formulations—of attempting to place micro foundations under macroeconomics was not something that infused policymaking in any important way," he said.

Searching for insights about what to do in a debt crisis, policymakers were forced to go back to older economic thinkers, such as Bagehot, Keynes, Minsky, and Kindleberger, Summers noted. "I was heavily influenced by the basic I.S.L.M. framework augmented to take account of liquidity traps," he said. Other things that came in useful, he added, were James Tobin's writings on debt deflation, modern theories of bank runs (which are associated with the economists Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig), and new thinking on restructuring and bankruptcy from the field of corporate finance.

Summers pointed out that he was an early critic of New Classical Economics and so-called real business cycle theory—much of which emerged from the work of Robert Lucas and colleagues. But I wish Wolff had pushed Summers on his embrace of an earlier generation of Chicago thinkers, particularly Milton Friedman. During the nineteen-nineties, when Summers was enthusiastically supporting financial deregulation from his perch at the Treasury, he frequently cited Friedman, who championed the theory that financial markets are efficient, and can therefore be largely left to their own devices. Characteristically reluctant to admit the possibility that he might have been in error, Summers gave a qualified defense of financial innovation, pointing out that many of the financial crises that have beset the world economy—including those in Ireland and Greece—had their roots in low-tech finance: bank lending to the real estate sector. Stepping lightly over the sub-prime meltdown, he averred: "Most financial crises don't seem to have their roots in financial innovations."

Before closing, Summers took a well-aimed shot at policymakers across the Atlantic. Wolff asked him whether the embrace of austerity policies in Europe, and particularly in Britain, wasn't "basically nuts." Summers replied: "I'm too soon out of government to use a word like nuts. But I find the idea of expansionary fiscal contraction, in the context of the world in which we live, to be every bit as oxymoronic as it sounds. And I think the consequences are likely to be severe for the countries involved."

Saturday's session began with a number of economic historians, including Berkeley's Barry Eichengreen and Robert Skidelsky, Keynes's biographer, pondering the lessons learned from the original Bretton Woods conference. At lunch, Gordon Brown, who was voted out of Downing Street last year, delivered a sweeping survey of global economic issues. Noting that he had recently enjoyed a "period of reflection, enforced reflection," he argued that most of the problems facing the world—financial instability, recessions, trade disputes, environmental degradation—"cannot be addressed on an individual basis and can only be resolved by global coördination."

In the area of financial regulation, Brown pointed out, coördination was sorely lacking, with some individual countries pursuing their own agendas and trying to cozy up to big financial institutions. "I believe we are going back to a race to the bottom," Brown said. During a question-and-answer session, Anatole Kaletsky, an economic commentator for the Times of London, made a pertinent point: it was Brown himself who had given an honorary knighthood to Alan Greenspan, the great deregulator. Faced with this high-inside fastball, Brown took evasive action, saying that from where he had been sitting—10 and 11 Downing Street—things had seemed very different. Rather than pursuing an agenda of deregulation, Brown said, he had spent most of his time resisting calls from the City of London to go easy on the financial sector.

The highlight of last year's INET conference was a lecture on the failures of mainstream economics from Lord Adair Turner, Britain's top financial regulator, who heads up the Financial Services Authority. (I was so impressed by Turner's speech that I quoted it in the paperback edition of my book, "How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities.") Invited back to give another keynote address, Turner on Saturday evening stepped back from the financial crisis and talked about the policy implications of so-called "happiness economics." As is now well known, surveys of individual well-being show that beyond a certain income threshold—about twenty thousand dollars a year—additional income and consumption produces little or no extra happiness. Countries get richer. Their residents earn more money and purchase more goods and services, but their reported levels of happiness stay pretty much the same. This is the so-called "Easterlin paradox"—named after Richard Easterlin, the American economist who first documented it. Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, two economists at Wharton, have recently queried its existence, identifying in the data a positive relationship between well-being and income. But even if you accept the findings of Stevenson and Wolfers, beyond a certain level the impact of additional income is very slight: in rich countries, most people are trapped on a "hedonic treadmill."

In view of the Easterlin paradox and other research showing that people's happiness falls sharply when their income drops or they lose their jobs, Turner argued that policymakers should do all they can to stabilize the economy and prevent recessions but concentrate less on increasing absolute growth rates. Whether the British economy grew over the next twenty years at an annual rate of 1.75 per cent or 1.9 per cent was a trivial question relative to preventing mass unemployment, Turner argued. This line of reasoning represented a return to the arguments of Keynes, Hansen, Modigliani, Samuelson, and others, who during the middle of the twentieth century placed macroeconomic stabilization at the center of economics. I pointed out to Turner in a brief conversation that it also represented a direct repudiation of Bob Lucas's 2003 presidential address to the American Economics Association, in which he said the issue of stabilizing business cycles had been largely solved and economists should concentrate their efforts on growth.

Some economists, such as L.S.E.'s Richard Layard, have taken the happiness research even further, arguing that it justifies a radical program of tax increases, income distribution, and environmental measures. In summing up, Turner said he wasn't willing to go this far. Despite the research he had cited, he said he broadly supported the notion of a market economy based around economic growth. But rather than relying on the usual economic-incentive arguments, Turner's justification for a pro-market view of the world was political: markets provided people with the "freedom to act as they like," limited taxes enabled them to "keep a significant share of the income they have earned," and (here Turner was quoting Keynes) competitive capitalism enabled unsavory people to tyrannize over their bank balances rather than over each other. As always, Turner's arguments deserve to be taken seriously. In this case, though, I thought he came close to contradicting himself. (In the Q. & A. session after his speech, a couple of questioners also raised this point.) Either you take the happiness research seriously or you don't. If you do—and Turner clearly does—then I don't see how you can simply pronounce yourself a nineteenth-century liberal and leap off the hedonic treadmill.

The conference ran throughout Sunday. It ended with the F.T.'s Gillian Tett interviewing Soros and Paul Volcker, the former Fed chairman. Fittingly enough, Volcker turned to the issue of international-monetary reform, which hitherto hadn't featured much in the conference despite its location. He recalled joining the Treasury in 1969 as under secretary for monetary affairs at a time when the original Bretton Woods system was still operating but running into problems. Today, he noted, there wasn't any formal international system but rather a de facto arrangement characterized by a lack of fiscal discipline and huge current account imbalances. "Who would ever sit down and think of designing a system that permitted China to get three trillion dollars worth of reserves, and for the U.S. to happily use all that money to run up housing prices?" Volcker said. "I think there really was a connection between the international monetary system … and the great financial crisis. And nobody has had any interest" in reforming it.

And that, pretty much, was that—save for a not-too-subtle putdown by Volcker of his successor, Alan Greenspan, which in itself was worth the journey to New Hampshire. Asked by Tett to comment on Greenspan's recent article in the F.T., in which he said financial reform was basically pointless, Volcker said: "On the face of it, without referring to Alan Greenspan, I can simply say I think the markets needed more regulation and the banks needed more regulation."

Note about the headline: It's another quote from Keynes, who was originally reluctant to attend the Bretton Woods conference, to which more than seven hundred delegates from forty-four countries had been invited. Keynes (wrongly) feared that nothing would get done and the result would be a "monstrous monkey house."

April 8, 2011

Paul Ryan's Interesting Suicide Note

There's nothing like leaving the country for a week or two to freshen your perspective on Washington's budget battles. What looks deadly serious from the banks of the Potomac and vaguely serious from the banks of the Hudson can seem from Europe or Asia like a long-running farce.

Surely, people said to me during my travels, the American government isn't going to close down over such a trivial dispute. (At last count, the difference between the two sides' spending proposals was seven billion dollars, which is less than a fifth of one percent of the federal budget.) Most probably not, I replied, but in Washington you can never be sure that logic will prevail, especially on the first go-round. Sometimes—October, 2008, was a recent example—it takes a meltdown in the markets to bring the pols to their senses.

On this occasion, I'm pretty sure the two sides will avoid a shutdown. What is really going on, I suspect, hasn't actually got much to do with shrinking what's left of the 2011 budget. It's more a matter of staking out positions for the bigger battles to come: the raising of the federal debt ceiling, which will be necessary next month; the 2012 budget, which goes into effect in October; and the long-term challenge of reducing entitlement spending.

But something significant did happen this week: Representative Paul Ryan, a Wisconsin Republican, fleshed out his supposed "road map" to fiscal balance, which involves radical changes (i.e., radical cuts) to Medicare and Medicaid. Basically, Ryan proposes replacing with a Medicare a privatized voucher scheme beginning in 2021 and forcing the states to restrict Medicaid by shifting to a block-grant system of financing.

The reactions to Ryan's road map have been predictable: Nancy Pelosi and Paul Krugman are outraged; David Brooks and Charles Krauthammer are supportive. I agree with Krugman that parts of Ryan's plan—the bits in which he proposes cutting taxes for the rich and slashing domestic spending in a manner that simply isn't credible—are bunk. As long as they remain part of the package, it cannot be seriously described as a deficit-cutting proposal. But I think Ryan's ideas for Medicare/Medicaid deserve another look.

To begin with, let's not underestimate how politically risky they are. The White House, I would imagine, is delighted because Ryan is proposing to make big cuts in retirement health-care benefits for people in their forties and fifties compared to what they would receive under the current system. The Congressional Budget Office, in a new analysis, makes clear that the value of the new Medicare vouchers wouldn't nearly cover the full price of services currently provided by Medicare. Poor and middle-income people would be forced to reduce their consumption of health services or forgo other expenditures. To put it lightly, this is not going to be popular. (For this reason, Krauthammer, despite his personal support for Ryan's approach, compares it to the U.K. Labour Party's 1983 election manifesto, which was aptly described as the longest suicide note in history.)

I agree with Jacob Weisberg that Ryan deserves some credit for at least putting a specific Republican proposal on the table. (I don't take the details of Ryan's plan as seriously as Jacob does.) It's been clear for years (decades, actually) that if something isn't done about Medicare/Medicaid they will eventually swallow the federal budget. (I recall attending a seminar in 1988 at which Barry Bosworth, an economist at the Brookings Institution, made precisely this point.) Now, finally, we have the outlines of two rival approaches to the problem.

Under the Obama health-care-reform blueprint, an independent commission of experts would recommend policies to limit the cost of Medicare and Medicaid, and Congress would be obliged to go along, sort of. Based on ideas successfully adopted by the British National Health Service, this approach would aim to spread best practices and eliminate wasteful procedures. Under the Ryan path, we would rely on brute force (making the vouchers worth less than the value of the services provided), state governors (block grants), and competition (vouchers) to do the cost-cutting job.

I have doubts about both plans. Given the relentless advances in medical technology and health-care inflation, I find it hard to believe that the independent commission will come up with enough savings to rein in spending. I find it equally hard to conceive of Congress slashing benefits to a politically powerful group, which is what moving to a voucher system would involve. And I am also skeptical of the argument that, in this particular industry, competition reduces costs. (America has the most competitive health-care system in the world—and also the most expensive.) My guess, and at this point it's not a very educated one, is that eventually both parties will be forced to embrace means tests and/or compulsory private medical savings accounts.

But anything that starts a serious debate is to be encouraged. Even if it comes from a "charlatan" (Krugman's phrase) like Ryan.

April 5, 2011

Alan Greenspan: The Fountainhead is Back

My thanks to Donald Low and his colleagues at the Civil Service College of Singapore, who played host to me last week. As a defender of public interventions to remedy market failures in a land where government is fast becoming a dirty word, it was refreshing to visit somewhere that takes pride in its official activism, and which draws some of its very smartest youngsters into the government sector.

While I was away, Alan Greenspan wrote a remarkable piece in the Financial Times criticizing the Dodd-Frank reform bill and the very concept of financial reform. At first, I thought the article was an early April Fool's joke—it appeared in the edition of March 30th—but apparently not. Having admitted in 2008 that the financial crisis had revealed a "flaw" in his free-market ideology, Greenspan has now reverted to full-on Ayn Rand Objectivism, noting that, "With notably rare exceptions (2008, for example), the global 'invisible hand' has created relatively stable exchange rates, interest rates, prices, and wage rates."

The Maestro reckons the Dodd-Frank bill amounts to "regulatory-induced market distortion" and is destined to fail. Why so? "The problem," says Greenspan, "is that regulators, and for that matter everyone else, can never get more than a glimpse at the internal workings of the simplest of modern financial systems."

What next? Marshal Joffre criticizing mobile warfare? Donald Rumsfeld attacking the notion of post-war planning? Jeffrey Skilling on the futile search for corporate transparency?

I was going to write a post pointing out that Greenspan is undoubtedly right about Greenspan-style regulators—the type that had no interest in the subject to begin with. It turns out that Barney Frank has already effected the necessary demolition job. Writing in Monday's FT, the Massachusetts Democrat points out that Greenspan's assertion about regulatory blindness "is self-fulfilling if regulators are not given the mandate or the tools to do so, or if they fail to use the tools they have." Frank also notes that Greenspan's renewal of his laissez-faire vows, "overlooks a monumental crisis that threatened the foundations of the American economy, led to soaring unemployment, a foreclosure crisis and weakened economies in the US and Europe."

I could go on and on about A.G., but, really, what's the point? Given the disastrous policy errors that he presided over, I can't help recalling Clement Attlee's famous remark to Harold Laski, another ideologue, during the 1945 election: "A period of silence from you would be welcome."

Photograph: Wikimedia Commons.

March 23, 2011

Austerity Britain: Lesson for the U.S.?

When I was growing up in Yorkshire, people tended to look to America for what was coming next—be it properly functioning showers, disco, or a revival in outmoded economic doctrines. Today, history is moving in the opposite direction, and we can look across the North Atlantic for instruction in what the U.S. economy may soon be facing, especially if the deficit hawks get their way.

Today was budget day in London, and George Osborne, the boy-faced Chancellor of the Exchequer, presented the Tory-Liberal coalition's economic plans for the next year. The headline-grabbing measure was a cut in gasoline taxes of one penny per liter—about six cents per U.S. gallon. That won't mean much to British motorists who are already paying more than eight dollars a gallon for "petrol." (Fuel levies in the U.K. are still much, much higher than they are here.)

The U.K. Treasury billed this as a package for growth, but that was a misnomer. The real news was the revelation that the government has downgraded its forecast for G.D.P. growth in 2011 from 2.1 per cent to 1.7 per cent. Since the previous forecast was only issued in November, this represents a reduction of almost a fifth in just five months. And many independent authorities believe the government is still being too optimistic. The London-based National Institute for Economic Research predicts growth of just 1.5 per cent this year and 1.8 per cent next year. Some pessimists, such as Nouriel Roubini, are warning of a double-dip recession.

Far from reversing the austerity policies he introduced following last year's election, Osborne reaffirmed them. While this budget was "fiscally neutral," meaning it won't have much impact either way on economic output, the government remains committed, over the next four years, to a swinging program of spending cuts and tax increases. The sales tax (VAT) has already been raised from 17.5 per cent to twenty per cent. Some government departments are seeing their budgets cut by a quarter, welfare payments are to be cut, and capital expenditures are being postponed. Libraries are closing, and local governments are preparing mass redundancies.

With a budget deficit of more than ten per cent of G.D.P., Britain clearly had to address the public finances. But rather than following the Obama model of introducing a short-term fiscal stimulus to revive growth and tax revenues, Osborne and his boss David Cameron opted for the cut-and-slash policy methods of Andrew Mellon and Philip Snowden—in an effort to balance the budget by 2015. At the time, I and many other observers said that the likely outcome of this absurd exercise in self-flagellation was a sharp dip in growth, and possibly even another recession.

It is a simple matter of arithmetic that when one source of demand in the economy—in this case, the government—cuts back its spending sharply, G.D.P. will fall unless another sector steps up its level of spending. But with Britain suffering from rising fuel prices and a housing bust, there was never much prospect of debt-laden consumers filling the stores or business embarking on an investment binge. Recent statistics confirm that this was wishful thinking. In the fourth quarter of last year, the U.K. economy shrank at an annual rate of more than two per cent: consumer spending and business investment both fell. Most independent experts think the first quarter of this year wasn't much better.

During the early nineties, a similarly deflationary period, Britain got lucky. Thanks to George Soros, the country crashed out of the European exchange-rate mechanism, the value of the pound collapsed, and exports surged sufficiently to buoy up the entire economy. In 2007 and 2008, it looked like Britain might get fortunate again. In the first months of the financial crisis, sterling tumbled about twenty per cent, and growth revived more quickly than it did in other Western countries. But since the start of 2009, the value of the pound has been rising again, and growth has stalled.

With consumer confidence at a record low and unemployment rising, the British economy badly needs a boost in domestic spending. The obvious way to generate it is to ease off on austerity policies and adopt a more gradual approach to balancing the budget. But Osborne and Cameron have staked their reputation on what was once called "the Treasury View" of public finance—that was before John Maynard Keynes went to work there—and, alarmingly, some people in Washington appear determined to follow their example.

Rather than giving in to the deficit hawks, President Obama should point out what is happening in Britain. Things still aren't great here—unemployment remains much too high—but the Federal Reserve is forecasting that the U.S. economy will expand by somewhere between 3.4 per cent and 3.9 per cent this year, more than twice as fast as the U.K. economy. To be sure, it would be unwise to attribute all of this divergence in performance to budgetary policy. But it would be far more unwise to assume that what is happening in Britain hasn't got anything to teach us here in the United States.

March 17, 2011

Fukushima and Toms River, N.J., Have the Same Reactors

I'll leave the scientific debate about nuclear power to better-informed colleagues. But here, courtesy of the Nuclear Information and Resource Service (an anti-nuke group) and confirmed by General Electric is a list of U.S. nuclear plants that have the same type of reactor as those at Fukushima: a General Electric Mark 1.

ReactorLocation Size Year operation began

Browns Ferry 1 Decatur, AL 1065 MW 1974

Browns Ferry 2 Decatur, AL 1118 MW 1974

Browns Ferry 3 Decatur, AL 1114 MW 1976

Brunswick 1 Southport, NC 938 MW 1976

Brunswick 2 Southport, NC 900 MW 1974

Cooper Nebraska City, NE 760 MW 1974

Dresden 2 Morris, IL 867 MW 1971

Dresden 3 Morris, IL 867 MW 1971

Duane Arnold Cedar Rapids, IA 581 MW 1974

Hatch 1 Baxley, GA 876 MW 1974

Hatch 2 Baxley, GA 883 MW 1978

Fermi 2 Monroe, MI 1122 MW 1985

Hope Creek Hancocks Bridge, NJ 1061 MW 1986

Fitzpatrick Oswego, NY 852 MW 1974

Monticello Monticello, MN 572 MW 1971

Nine Mile Point 1 Oswego, NY 621 MW 1974

Oyster Creek Toms River, NJ 619 MW 1971

Peach Bottom 2 Lancaster, PA 1112 MW 1973

Peach Bottom 3 Lancaster, PA 1112 MW 1974

Pilgrim Plymouth, MA 685 MW 1972

Quad Cities 1 Moline, IL 867 MW 1972

Quad Cities 2 Moline, IL 867 MW 1972

Vermont Yankee Vernon, VT 620 MW 1973

For those of you unfamiliar with the Northeast, Toms River is located in one of the most densely populated suburban areas in the United States, and is about seventy miles south of New York City. More information on the debate over the safety of these reactors, which goes back forty years, can be found on the NIRS Web site. G.E.'s view of the issue can be found here.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers