John Cassidy's Blog, page 112

October 18, 2011

Memo to David Brooks: It's a Great Recession, not a Great Restoration

I usually take the pop philosophizing of David Brooks with a pinch of salt. Floating grand theories that turn out, on closer inspection, to be largely ether is one of the jobs of professional pundits. (I should know!) Brooks is intellectually curious, a felicitous writer, and occasionally he even queries his own beliefs in print—an exercise that some of his colleagues on the Times Op-Ed page might care to mimic once a decade.

But today's column, in which Brooks espies an epochal shift in American values, I can't allow to pass without comment. Dismissing Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party as overhyped minority pursuits, Brooks stares into the tortured soul of Middle America and sees a born-again Calvinist tearing up her credit cards and bemoaning the culture of bailouts. "While the cameras surround the flamboyant fringes, the rest of the country is on a different mission," Brooks writes. "Quietly and untelegenically, Americans are trying to repair their economic values … the moral norms that undergird our economic system."

I am tempted to ask D.B. whether he has turned on prime-time television lately, or visited Las Vegas, the site of tonight's Republican debate, but tacky reality shows, cavernous gambling halls, and upscale jiggle joints are, perhaps, part of the "flamboyant fringes" of American society. So let's look at the evidence that Brooks cites, beginning with an opinion poll suggesting that three quarters of Americans think they would be better off with no debt and the fact that eight million people have stopped using bank-issued credit cards.

The figure for credit-card usage is accurate enough, but it has nothing reason to with values. The reason many people are carrying fewer pieces of plastic in their wallets is that banks, considering them to be bad lending risks in a deep recession, have cut off their access to credit.

The opinion survey Brooks cites is the latest Allstate/National Journal Heartland Monitor Poll, which was released last week. Ron Brownstein wrote a long piece about it in the National Journal (pdf). Here is part of what he wrote:

For most Americans, debt remains more of a chronic than an acute concern. Asked to identify their biggest financial worry, just 8 percent identified carrying too much debt, which ranked it behind the cost of living; an inability to save enough for retirement; earning too little; finding or keeping a job; and declining home values. (An equal 8 percent worried about poorly performing investments.) About 25 percent of those polled said that their debt load had increased in the past few years—a substantial but not overwhelming number. Even more (31 percent) said they had reduced their debts, and 41 percent said that their debt levels hadn't changed much.Just 11 percent of those polled said they considered their current level of debt "dangerous" and harbored "serious concerns about being able to pay it off." Slightly more than two-fifths said they considered their debts "manageable" and held "little concern about being able to pay it off." The largest group hedged: 47 percent said that their debts were "somewhat worrisome, but as long as nothing bad happens, I should be able to pay it off."

Mmm. Does this sound like a nation that, in Brooks' words, is "reacting strongly against the debt culture"? Assuming the sample is representative of the country as a whole, two-thirds of Americans have the same amount of debt or more debt than they had a few years ago, and nine out of ten of them consider their debts to be manageable or only somewhat worrisome. Just one in twelve and a half Americans regard debt as their biggest financial concern.

But what about the finding that three-quarters of people say they would be better off without any debt? That is encouraging, I agree. It demonstrates that a healthy majority of Americans still understand elementary arithmetic. If you expunge your debts and keep your assets, then, by definition, you are better off.

Brooks's entire argument doesn't hinge on borrowing patterns. He also perceives that "Americans are trying to re-establish the link between effort and reward" and that today, as opposed to yesterday, "loyalty matters." The former assertion he bases on Sarah Palin's most famous contribution to political science: Americans dislike bailouts.

But surely this has always been true. What has changed in the three years since October, 2008, when the House Republicans, riding a wave of public anger, voted down the Hank Paulson's initial TARP program, only to reverse course when the markets tanked? Not very much, I would guess. Take the auto bailouts, which saved GM and Chrysler from bankruptcy. Earlier this month, the polling organization Rasmussen found that fifty-one per cent of Americans still regard them as a bad idea. Polls taken in December, 2008, when the auto bailouts were first mooted, showed even less support for them. For example, a CNN poll carried out on December 1-2, 2008, suggested that sixty-one per cent of Americans were against providing government assistance to the auto companies.

Finally, there is the question of loyalty, by which Brooks means employee loyalty. According to his snappy narrative, the age of "Free Agent Nation" has passed, and "now most people, even most young people, would rather work long-term for one company than move around in search of freedom and opportunity." On what empirical evidence this is based, the article doesn't say.

I have always regarded the "Free Agent Nation" theory, which dates back to a 1997 article in Fast Company, as largely tosh. To be sure, more people were quitting their jobs during the boom years, but that was a rational response to a tight labor market. When there are more jobs available, employee turnover always increases. Now that jobs are much harder to come by, it makes perfect sense to buckle down and tell everybody (pollsters included) how much you love your employer.

As for the rise in the ranks of the self-employed during the past decade or so, I suspect that was largely a response to downsizing on the part of corporations. For every Harvard Business School graduate who turned down a job at Goldman Sachs or McKinsey to start his own Web site or coffee-shop empire, there were hundreds or thousands of middle-aged people who had been forced, through no fault of their own, to repackage themselves as "freelance consultants." With the Great Recession came another big wave of job shedding, and another jump in the number of people categorized as self-employed. Revisions carried out earlier this year to the figures collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that there are now about fourteen million self-employed Americans, compared to a previous estimate of roughly nine million. One way to spin that statistic is to say that Americans have rediscovered the get-up-and-go entrepreneurial spirit that made this country great. The truth, of course, is very different.

History shows that extended slumps generate big changes in social and economic behavior, many of which involve a lot of frustration and suffering. They also tend to transform the political landscape. Extremism flourishes and ideas previously regarded as outlandish get a hearing. Sometimes this leads to tragedy: Weimar Germany provides the most famous example. Sometimes, as in F.D.R.'s America, it leads to progress. Of course, the Great Recession isn't the Great Depression, and Occupy Wall Street isn't the Bonus Army descending on the Potomac. Equally, however, it isn't just a bunch of Bard College students looking to reprise the Situationist International. Although there's a bit of that, to be sure, the revolt against mainstream politics, on the left and the right, is palpable and important.

I don't want to be too harsh on Brooks. Coming up with something new and interesting to say twice a week isn't easy, and he does it better than most. But searching for upsides in the economic calamity that has befallen the country, and downplaying the sense of outrage among ordinary Americans, is a dubious enterprise.

October 17, 2011

CNN Poll: Romney and Cain Neck and Neck

On the eve of yet another television debate among the Republican candidates, a new poll from CNN/Opinion Research International (pdf) provides a convenient snapshot of the race and how it has changed over the past month or so.

Here's the key data on voting intentions among 416 self-identified Republicans.

[image error]

All the rest of the candidates are in the single digits. The poll confirms Herman Cain's recent surge and Rick Perry's collapse—no surprise there. But contrary to the received wisdom, it also suggests that Mitt Romney is picking up more support. If other polls confirm this finding, it will strengthen the argument that Romney, despite a fresh wave of stories about his Mormon religion, including this erudite hatchet job by my old cobber Christopher Hitchens, is fast becoming "Mr. Inevitable."

Two notes of caution, though. Since the poll's margin of error is five per cent, Romney's recent surge is not quite statistically significant. And two thirds of the Republicans sampled said they might yet change their mind and vote for somebody else.

On the other side of the political divide, the poll suggests that President Obama still has a lot of work to do in firing up his base. Less than half—43 per cent—of registered Democrats were "extremely enthusiastic" or "very enthusiastic" about voting next November. On the eve of the 2008 election, the comparable figure was almost four fifths—79 per cent.

Now, you'd expect there to be more voter enthusiasm a few days before an election than there is thirteen months prior to polling day. But the trend appears to be going in the wrong direction for Obama. As recently as June of this year, more than half—55 per cent—of registered Democrats said they were "extremely enthusiastic" or "very enthusiastic" about voting.

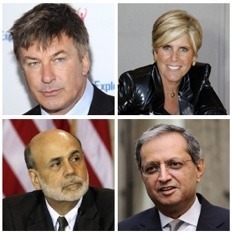

Top Ten Unlikely Occupy Wall Street Supporters

10) Henry Blodget: Disgraced Wall Street analyst turned online media mogul empathizes with the mob. Provides handy charts to back up case.

9) Suze Orman: Schoolmarmish personal-finance maven says banks deserve to be criticized. Grades OWS as "approved."

8) Deepak Chopra: New Age guru leads protesters in a group meditation. Tells them to go to place of "compassion, centered equanimity, and creativity."

7) Larry Fink: Head of world's biggest asset-management firm says demonstrators "are not lazy people sitting around looking for something to do." (Not to be confused with the photographer Larry Fink, who also supports the protests.)

6) Bill Gross: Manager of world's biggest bond fund says it's no surprise the 99% is fighting back "after 30 years of being shot at."

5) Charles Moore: Tory sage and official biographer of Mrs. Thatcher says he is starting to think the left "might actually be right."

4) Alec Baldwin: Actor and Capital One front man tweets support and advice to protesters. (Not clear if he's donated the fees from his ads to OWS, though.)

3) Jeffrey Sachs: Columbia economist and former godfather of free-market shock therapy visits Zuccotti Square and tells protesters they are on right track.

2) Vikram Pandit: Citigroup chairman says "trust has been broken" between Wall Street and Main Street. Offers to meet with demonstrators.

1) Ben Bernanke: Republican-appointed Fed chairman says he "can't blame" protesters for taking to the streets.

October 14, 2011

What 9-9-9 Would Cost the Middle Class

[image error]

After putting up my previous post about Herman Cain's tax plan, I did a bit more reading about it. Guess what? The plan turns out to be even more regressive than I had thought, and, moreover, it is a "9-9-9" plan in name only.

On the plus side, the plan is less of a deficit-buster than it first appears. But that's because it would effectively tax workers at a rate of eighteen per cent, not nine, thereby raising a great deal more revenue. Adding in the sales tax makes the Cain tax proposal even more onerous. A more accurate description of it would be an "18-9" plan.

Once you think of the plan this way, it resolves a question that has been hovering over it since the beginning: How can Cain say he will raise enough money to support the federal government with a flat rate of nine per cent when most serious analyses suggest that it would take a flat rate of at least seventeen or eighteen per cent to do the job? The answer is that Cain's plan is actually an eighteen-per-cent plan disguised as a nine-per-cent plan.

In a new study, some of whose conclusions I referred to earlier, Edward D. Kleinbard, a former staffer at the Joint Committee on Taxation, has laid out how the plan would work. Until I looked at the details of Kleinbard's paper, I hadn't grasped the key point, which is the nature of Cain's nine-per-cent tax on business profits. Like many others, I had assumed that Cain would maintain the existing corporate income tax and simply slash the rate from its current level, which ranges from fifteen per cent for small businesses to thirty-five per cent for large corporations. But that isn't at all what would happen.

For tax purposes, businesses are currently allowed to deduct the wages and salaries they pay from their gross income. Under Cain's plan, the deduction for wages and salaries would be abolished, meaning that the "profits" that firms report to the I.R.S. would be much higher, as would their tax bills. Firms would then seek to pass on the higher taxes to workers in the form of lower wages.

To show how this would work, let me offer up a simplified example that is based on Kleinbard's analysis. Take a firm with gross revenues of a hundred million dollars that pays fifty million dollars in wages and salaries and forty million dollars in other costs (raw materials, advertising, and so on). Under the current system, the firm's taxable profits are ten million dollars, and its tax bill is $3.5 million.

Under Cain's proposal, since the firm could no longer deduct the fifty million in wages and salaries, its taxable profit would jump to sixty million. At a tax rate of nine per cent, its tax bill would be $5.4 million. If you compare this figure to $3.5 million, you will see that the firm's effective tax rate would jump by more than half under the Cain plan. When applied to firms throughout the economy, such a tax hike would generate a very big jump in revenues from the business tax despite the fact that it was being levied at a lower rate.

On this basis, the Cain campaign may be exaggerating only modestly when it estimates that the federal government would have raised about eight hundred billion dollars in business-tax revenues in 2008. As far as the budget deficit is concerned, that's good news. But who would end up paying these taxes? At first glance, it looks as though businesses would. They would figure out their tax liability under the new rules and wire the money to the I.R.S. However, that is only half the story. Faced with a huge increase in their tax bills, firms would seek to pass the burden on to their employees in the form of lower wages and stingier benefits.

How much of it would they be able to pass on? According to most economic studies that have looked into this type of question, the answer is almost all of it. The "incidence" of such taxes falls almost entirely on workers. (The technical reason for this is that the supply of labor is less sensitive to the level of wages than the demand for labor.) Ultimately, rather than paying nine per cent of their income in income taxes, workers would face a rate of close to eighteen per cent. Half of these taxes the I.R.S. would collect directly. The other half employers would deduct from workers' paychecks and pass on to the government.

With almost all existing deductions and tax credits to be abolished under the plan, there wouldn't be any way for people to get around these taxes. In addition, don't forget, there is the nine-per-cent sales tax. There'd be no way around that, either, unless you choose to save some of your income, which many poor and middle-income families can't afford to do.

One of Cain's arguments for his plan is that it would abolish the regressive payroll tax. But, as Kleinbard points out, the plan would end up looking much like a new payroll tax levied at a higher rate, with no upper limit on the income it applies to. Adding the nine-per-cent sales tax to the eighteen-per-cent tax on income produces an over-all tax burden of close to twenty-seven per cent, which would apply to every dollar of income that is earned and spent. "In sum," Kleinbard writes, "the 9-9-9 Plan operates on wage earners as an effective 27 percent uncapped payroll tax applied from the first dollar of wage income—not an elimination of the payroll tax at all!"

That may be pushing things a bit far. I think it's more accurate to describe Cain's proposal as an "18-9" plan. But Kleinbard's basic point is sound. The more you look at it, the less attractive it seems.

Photograph by Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images.

Common Sense Breaks Out at City Hall

The city's last-minute decision not to evict the Occupy Wall Street hordes from Zuccotti Park, at least for now, represents a rare sensible decision by the Bloomberg administration in its reaction to the protest. If the Mayor had gone ahead and sent the N.Y.P.D. in to clear out the square, supposedly for a cleaning, the police would have had to arrest thousands of people live on television, which would have been a public-relations disaster for Bloomberg and for the city.

In stepping back, Bloomberg and Ray Kelly, the police chief, have given themselves some time to seek an agreement with the demonstrators. Even if these negotiations fail, as they may well do, the city will have given the impression that it tried to act reasonably rather than simply trying to bash the protestors into submission.

Spare me the official line that Brookfield Properties, the owner of the "public private" park, had second thoughts about asking for the N.Y.P.D.'s help in cleaning it up. The mayor, whose girlfriend Diana Taylor is a director of Brookfield, is driving this van, and Kelly is in the passenger seat.

Bloomberg's distaste for what is happening has been clear from the beginning. That's hardly surprising. The Occupy Wall Street folk have put him in the invidious position of overseeing a protest against the industry that created his fortune and, by extension, his mayoralty. But disliking a protest is one thing. Ordering the police to break it up at dawn, with force if necessary, would have placed in jeopardy his entire political identity as a cool-headed problem solver. If he hadn't been careful, he could easily have ended up looking like an out-of-touch billionaire trying to defend his own class-interest.

In his radio show this morning, Bloomberg was clearly trying to strike an equitable and impartial note. "The protestors, in all fairness, have been very peaceful there," he said. But he then went on to cite the concerns of the people living in the neighborhood of Zuccotti Park, adding, "The longer this goes on, the worse it is for our economy."

Now, the Mayor's representatives can meet with some of the protest leaders and try to reach a compromise. Legally, it seems clear that Brookfield has the right to enforce "reasonable" rules of conduct in the park, which it can define to include not sleeping there or creating a camp. But will the protestors be willing to accept such limitations?

If the Mayor is in a tricky spot, so are the protest organizers. After a month in which they have succeeded beyond any expectations, the protesters now have to ask themselves some tricky questions. Is Occupy Wall Street a movement about occupying a piece of real estate in lower Manhattan, or is it about something broader? The answer is clearly that it is about something broader—rising inequality and a corrupted political system—but how should this campaign be prosecuted from here on out?

There isn't an immediately obvious answer. But over the next few days, somebody is going to have to come up with one and persuade the rest of the movement to go along with it.

October 13, 2011

Herman Cain's 9-9-9 Plan: The Return of Trickle-Down Economics

Now that some opinion polls have Herman Cain leading the race for the Republican nomination, it is time to take a closer look at his "9-9-9" economic plan, which is the centerpiece of his campaign. For those of you who are in a hurry, here is the takeaway:

It doesn't raise enough revenue. Without offsetting cuts in spending, it would send the budget deficit skyrocketing.

It would be extremely regressive. Poor and middle-income people would pay higher taxes. Rich people would pay a lot less.

Its impact on growth is debatable.

Let's start with Cain's campaign Web site, which lays out the bare bones of the plan on a single page. If you think this isn't very much for a proposal that would junk the entire tax code, you are right. Still, here's what Cain has to say. The plan has two phases:

Phase 1: "9-9-9" Abolish the payroll tax, which pays for Social Security and Medicare, the capital-gains tax, inheritance taxes, and taxes on dividends. Abolish the graduated income tax and replace it with a flat tax of nine per cent. Abolish the graduated corporate income tax and replace it with a flat tax of nine per cent. Introduce a new nine-per-cent national sales tax.

Phase 2: "The Fair Tax." What is this? It isn't defined, but it appears to involve making the Phase 1 changes permanent. Cain simply says, "Amidst a backdrop of the economic boom created by the Phase 1 Enhanced Plan, I will begin the process of educating the American people on the benefits of continuing the next step to the Fair Tax. The Fair Tax would ultimately replace individual and corporate income taxes. It would make it possible to end the IRS as we know it."

The key to the plan's appeal is its simplicity. Rather than waiting until after next year's election, he is calling on the congressional "super committee" to introduce Phase 1 now. "America can't wait for 2012," he says. "We need growth NOW."

Surely, we do. But how would Cain's plan work in practice? In addressing any tax proposal, it is important to look at its likely impact on three things: fiscal sustainability (how much money would it raise?); income distribution (who would benefit and who would lose?); and economic growth.

Up until now, Cain hadn't provided any figures or projections to answer any of these questions. Yesterday, however, Richard Lowry, a wealth manager from Cleveland whom Cain referred to in Tuesday's debates as somebody who had worked on the 9-9-9 plan, told Bloomberg it would have raised about $2.3 trillion in 2008, which is roughly what the existing tax system raised. Of that $2.3 trillion figure, about $860 billion would have come from businesses, $700 billion from individual income taxes, and $750 billion from the sales tax, Lowry said. Apparently, these figures were put together by a financial advisory firm called Fiscal Associates, which is based in West Bloomfield, Michigan.

Are they credible? The figures for income taxes and the sales tax are higher than but roughly in the same ballpark as estimates from independent experts. But Cain's $860 billion figure for business taxes seems very, very high. In a critical analysis of Cain's plan, Michael Linden, the director of tax and budget policy at the Center for American Progress, has estimated that in 2007 a nine per cent corporate flat tax would have yielded $112 billion—almost $750 billion less than Cain's estimate for 2008!

Linden calculates that under the Cain structure overall federal taxes in 2007 would have totaled about 9.5 per cent of G.D.P., which is barely half the actual figure of 18.5 per cent. "Even if we reduced federal spending to the 'historical average' (when the population was younger and health care cost much less) it would still leave us with deficits over 11 percent of GDP (bigger than any deficit since WWII, including the deficits of the past three years)," Linden noted.

What about the distributional question? On the face of it, reducing the federal income-tax rate to nine per cent sounds like a big pay cut for the average person. But that is misleading. Under the current federal tax system, almost everybody is allowed to deduct from their gross income a $5,800 standard deduction and a $3,700 personal exemption. On top of that, there is the child credit, the child-care credit, the earned-income tax credit, the mortgage interest deduction, and various other deductions—all of which serve to reduce the effective tax burden. Cain would do away with all of this, and he would also impose a nationwide sales tax on everything from bread to clothes to cars.

Consequently, a lot of Americans would end up paying higher taxes. How much higher? According to a new analysis by Edward D. Kleinbard, a former staffer at Congress's Joint Committee on Taxation, a typical family of four with $120,000 in wage income would face an annual tax increase of $800. Many poorer Americans would face a much more substantial tax hike. Under the current system, with its various deductions and tax credits, many poor and middle-income families pay little or no federal income tax: their federal tax burden consists mainly of the payroll tax. Under Cain's plan, there wouldn't be a payroll tax, but all families would have to pay the new nine-per-cent rate on their income, and they would also have to pay the new nine-per-cent sales tax. Take a family earning about $50,000 a year, which isn't far from the median household income. All told, it could face tax a hike of $2,500, or even more, according to some estimates.

As for the richest people in the country, who earn much of their income in the form of interest, dividends, and capital gains generated by their existing capital, they would benefit enormously from the abolition of the capital-gains tax and the tax on dividends that Cain proposes. According to Linden, a typical Americans in the richest one per cent would see his tax rate fall from twenty-eight per cent to eleven per cent. Other tax experts using slightly different classifications nonetheless come up with similar figures. Roberton Williams, of the non-partisan Tax Policy Center, tells the Christian Science Monitor that the effective tax rate on people in the highest tax bracket would fall from twenty-one per cent to nine per cent. In short, the Cain plan would involve an unprecedented shift in the tax burden from the rich to the middle class and the poor.

That leaves the plan's impact on growth. In cutting overall federal taxes, it could give a boost to demand. But since the tax cuts would be focussed on the rich, who tend to spend less of their income proportionately, the normal Keynesian effect would be dampened. And if the prospects of even higher deficits spooked the bond markets, it could disappear completely. Cain, of course, makes the supply-side argument that raising the returns to risk-taking would spur investment, hiring, and productivity growth. Without any actual economic projections to look at, it is hard to evaluate. If you are disposed to believe this argument, there is probably nothing I could say to dissuade you, anyway.

So far, Cain has benefitted greatly from being the only candidate with a simple, snappy economic plan. As it receives more attention, this may well change. For example, consider seniors—a category of the population in which Cain appears to be polling well, especially in states like Florida. Do these folks realize he is proposing to hit many of them with a tax hike? Today, most seniors don't pay payroll taxes, and they have moderate incomes. Consequently, their tax burden is low. Under Cain's plan, whatever income seniors receive would be taxed at nine per cent, and so would their expenditures. In Florida, the sales tax on early-bird specials would jump from six per cent (the state sale tax) to fifteen per cent.

Wait until they figure that out in Sarasota and Fort Lauderdale!

Photograph by Daniel Acker/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

October 12, 2011

A Nobel for Freshwater Economics

This week's announcement of the Nobel Prize in Economics got me thinking about the state of the subject, and my thoughts weren't very positive. Three years after the great financial crisis of 2008 discredited the ruling orthodoxy in macroeconomics and finance, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has chosen to honor one of the leading creators of that orthodoxy: Tom Sargent, of New York University. And judging from the reactions to the Nobel announcement, most academic economists heartily approved of it.

A couple of years ago, it seemed like there was at least some willingness inside the economic profession to take outside critiques seriously. The successful launch of George Soros's Institute of New Economic Thinking, which attracted participants from a wide range of backgrounds, appeared to reflect a new spirit of openness. More recently, there has been a closing of the ranks, and I fear that the Nobel award will only strengthen that movement. What next? A Nobel for Gene Fama, the exponent of the efficient-market hypothesis? If Sargent deserves a Nobel, surely Fama deserves one, too.

If the economics Nobel is about rewarding influential economists, Sargent's award is a no-brainer. But aren't Nobels supposed to have a higher purpose? Aren't they supposed to be about rewarding people who put forward ideas and theories that turned out to be useful and practical? Looked at from this perspective, the Nobel committee should have picked out one of the economists who stood up against the ruling orthodoxy in macro, not one of its highest high priests.

Sargent shared the prize with Christopher Sims, of Princeton. The award to Sims I have no quibble with. Starting in 1980, he developed a new statistical approach to analyzing the economy, which today is widely used in central banks, universities, and economic-research firms. (Over at Marginal Revolution, Tyler Cowen has an informative post with some good links.) Known as Vector Auto Regression, or VAR, Sims's methodology enables researchers to make predictions and analyze policy changes without committing to a particular economic theory, but, rather, by seeking to let the data speak for itself. Whether VAR truly represents a big improvement over other statistical methods, such as the construction of large-scale Keynesian models or the calibration of smaller real-business-cycle models, is still up for debate. Some smart people, such as the authors of this paper, think it is economics without the economics. So far, though, VAR appears to have passed the market test.

Sargent's award is another matter. In one sense, it is long overdue. The economics Nobel is an inside job: the Economic Sciences Prize Committee, which advises the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, is largely made up of academic economists. Year after year, they give the award to one (or more) of their own (mostly Americans) whose work twenty or thirty years ago generated a lot of subsequent research, as Sargent's has. Back in the mid-seventies, he helped create the "rational expectations" approach to macro, which, speaking roughly, says that people form expectations about the future on the basis of an accurate model of the economy that they have in their head. This idea isn't very plausible, but for reasons partly having to do with the problems that Keynesian policymaking was encountering at the time, and partly having to do with the difficulty of incorporating expectations into economic models in any other manner, it proved immensely influential.

Today, no self-respecting economist would dispute the fact that forward-looking expectations matter a lot and that the actions of policymakers help to shape them. Even economists who refer to themselves as Keynesians are very careful in how they treat expectations.

That is largely Sargent's legacy. It has always been a mystery to me why he and his collaborator Neil Wallace, who now teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, didn't share the 1995 Nobel, which went to another pioneer of rational expectations, Robert Lucas, of the University of Chicago. The papers that Sargent and Wallace wrote in the mid-seventies, and the graduate textbooks Sargent published, proved just as influential as Lucas's work. It was Sargent and Wallace who purported to demonstrate that under the assumption of rational expectations changes in monetary policy on the part of the Fed that are anticipated by the public will have no impact at all. If the Fed printed more money to boost output and employment, workers and firms would revise wages upward in the expectation that inflation would rise; real (inflation-adjusted) wages would remain unchanged, and so would output and employment. This argument, which is known as the "policy-ineffectiveness proposition," helped to discredit Keynesian fine-tuning in some quarters.

The Lucas, Sargent, and Wallace approach to economics wasn't just about criticizing government interventionism. It came with its own methodology, which involved trying to build everything up from micro foundations with some snazzy new mathematics. (New to economists, that is.) This abstract approach, which is often referred to as "freshwater economics," eventually came to dominate the teaching of macroeconomics, first in the United States and then in other countries, too. The students and acolytes of Lucas and Sargent took over many of the top professorships and journals. Eventually, it got to be difficult for young scholars to publish articles that challenged or ignored the Lucas-Sargent methodology.

Unfortunately, in case it needs restating, freshwater economics turned out to be based on two ideas that aren't true. The first (Fama) is that financial markets are efficient. The second (Lucas/Sargent/Wallace) is that the economy as a whole is a stable and self-correcting mechanism. The rational-expectations theorists didn't refute Keynesianism: they assumed away the reason for its existence. Their models were based not just on rational expectations but on the additional assertion that markets clear more or less instantaneously. But were that true, there wouldn't be any such thing as involuntary unemployment, or any need for counter-cyclical monetary policy.

Perhaps because they wanted to head off this sort of criticism, the Nobel committee said that it was honoring Sargent not for his original work on rational expectations and economic policy but for his contributions to "econometrics"—the application of statistics to economics. But if this is a distinction it is a very fine one. Sargent's econometric research explored the implications of the rational-expectations hypothesis for testing theories. In the mind of every economist I know, he is still closely associated with rational expectations and its later refinements.

To be sure, he also did some other interesting work. In the eighties and nineties, he delved into the more realistic environment of bounded rationality, in which people don't know the true model of the economy but seek to learn about it in a systematic way. In such a world, as you might expect, it is much more difficult to reach sharp conclusions, or offer black and white policy advice, than under the assumption of rational expectations.

But Nobels aren't awarded for interesting research: they are awarded for research that changes how we think about the world. Freshwater economics did that. Eventually, though, it came a cropper. And it is not as if Sargent has acknowledged its failings. In a 2010 interview with the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, he staunchly defended it, saying it was designed to explain how the economy works in normal times, not in times of crisis. But this won't do, surely. The lesson of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession is that in a modern financially driven economy, it is what happens in "normal times" that gives rise to instability.

This was the central point that the late Hyman Minsky put forward repeatedly, and which economists of the freshwater persuasion resolutely ignored. Unfortunately, Minsky isn't around to collect the Nobel Prize, and neither is Charles Kindleberger, who helped to popularize Minsky's theories. Even if Minksy and Kindleberger were still alive, I doubt the Nobel committee would have invited them to Stockholm. If they had wanted to honor somebody who has done interesting work in the tradition of Keynes-Minsky-Kindleberger, which actually had something useful to say about the financial crisis and subsequent recession, they could have picked out Axel Leijonhufvud, of U.C.L.A., Paul Davidson, of the University of Tennessee, or Jean Pascal Benassy, of the Paris School of Economics. But to make such a bold move would have been to publicly acknowledge what Willem Buiter, a former London School of Economics professor who is now the chief economist at Citigroup, wrote on his blog in March 2009: "The typical graduate macroeconomics and monetary economics training received at Anglo-American universities during the past 30 years or so, may have set back by decades serious investigations of aggregate economic behavior and economic policy-relevant understanding. It was a privately and socially costly waste of time and resources."

It will be interesting to see what Sargent has to say in Stockholm. Hopefully, now that he has finally got his Nobel, he will be more willing to take seriously the criticisms of freshwater economics. But I wouldn't bet on it.

October 11, 2011

Winner of the Republican Debate: Twitter

One of the delights of Twitter, I am rapidly discovering, is that it relieves you of the obligation to think for yourself. You fire up your home page, and there they are: rolling news plus a handy collection of ready-made conclusions about practically everything under the sun. Take last night's Republican presidential debate, which was scheduled to end at ten o'clock.

At 9:54, Ezra Klein, the Washington Post's uberwonk, tweeted, "Debate wrap: Romney won. Not-Romney, not-Romney, not-Romney, not-Romney, not-Romney, not-Romney and not-Romney didn't." Two minutes later, my esteemed colleague Ryan Lizza asked, "Perry supporters, what's best case for Perry success tonight? Am I being too harsh saying he's mortally wounded?" At nine fifty-nine, Donna Brazile, the veteran Democratic Party strategist, pronounced: "Tonight's winners…Romney and Cain (9-9-9). Losers: Perry and Huntsman. Perry needed to score big and Huntsman needed to win big."

And that, pretty much, was that—or so I thought as I sat down to write this post. With the candidates still on the stage in Hanover, the narrative of the new mainstream media, which is what Twitter must now be regarded as, had already been articulated and distributed. Watching a couple of the political shows after the debate finished, I didn't see any of the talking heads diverge from it. Indeed, most of them appeared to have been checking their smart phones for guidance: Perry "came in on a downward trend," Matthew Dowd, the former Bush campaign strategist, said on Bloomberg Television. "He didn't do anything to change that trend."

In a sense, this represents progress. Rather than having to listen to grizzled Washington pundits stating the obvious in post-debate commentaries and columns, we now have clued-in young reporters like Ezra and Ryan, as well as knowledgeable insiders such as Brazile, to provide us with cheat sheets in real time. But did Romney and Cain really "win" the debate, and was it such a disaster for Perry? Absent new polling data from Republican voters, it was impossible to fact-check the Twitter narrative.

For what it is worth, I basically agreed with the Twitter narrative. However, from where I was sitting, the debate had mainly confirmed what we already knew. Mitt Romney 2.0 is a slick and formidable candidate—c.f. the impressive manner in which turned around Perry's question about his controversial Massachusetts health care plan, pointing out that Texas now has more than a million children without health insurance, and ending with the statement, "I care about people." Herman Cain is the only candidate with a distinctive economic plan and a direct, folksy speaking manner. Perry is struggling mightily in the major leagues. Given a chance to refute Romney's attacks with a defense of his own Texas healthcare reforms, he instead chose to bang on about Medicare block grants. Evidently, he had come up with a new jobs plan based on exploiting America's energy resources. But rather than detailing it to a national audience, he promised to roll it out in the coming days, when his media following would mainly consist of campaign correspondents on death watch.

And yet, to answer Ryan's tweet, I thought it was a bit premature to say Perry was mortally wounded, even if, as the Times' David Leonhardt informed us in a Tweet shortly after the debate finished, Intrade, an online political futures market, "now gives Assad a larger chance of being ousted this year (15%) than Perry of being the R nominee (13%)." For all his errors of omission, Perry hadn't made any obvious gaffes. By his standards, this was a big improvement. Despite his poor performances in the previous debates and the controversy over the existence of a racial slur on a gatepost at his family's hunting lodge, he seemed to still have an opportunity to turn things around. It was three months until the first primary. In this media-addled age, that is practically an eternity. He wasn't in any immediate danger of running out of money—he reportedly has fifteen million dollars in the bank. And his polling numbers were so low that if he staged any sort of resurgence it would have enabled him to repackage himself as the Comeback Kid.

Then I checked Twitter again, and saw this update from Ryan: "Perry post-debate: 'Reason we fought the revolution in the 16th century was to get away from that kind of onerous crown.' " Uh, oh! A few minutes later, Garance Franke-Ruta, a senior editor at The Atlantic, tweeted this: "The hashtag for the implosion of the Perry campaign is #perryhistory"

Indeed, he may be. But the Twitter campaign, I would say (confidently if not exactly originally) is going to have more staying power.

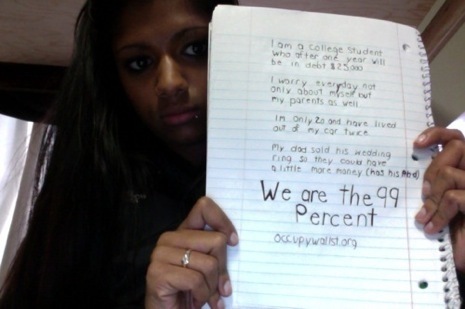

Wall Street Protests: Who Are the 99% and What Do They Want?

Fascinating post by Mike Konczal at Rortybomb on the makeup of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Rather than going down to Zuccotti Square with his notebook, Konczal analyzed the personal profiles that about a thousand of the protesters have posted at We Are the 99 Percent, one of the Web sites associated with the movement.

Konczal found that the median age of the protestors is twenty-six, a bit older than I would have predicted on the basis of my trips downtown. The average age is twenty-nine, which means there are quite a few older people involved.

In order to figure out what is driving the movement, Konczal wrote some computer code that extracted the words used most frequently in the profiles, where people tell their own stories. The ten most popular words were: "job," "debt," "work," "college," "pay," "student," "loan(s)," "afford," "school," "insurance." On the face of it, these results suggest the primary issue for the protesters is excessive student loans. Together with the median age being twenty-six, this lends credence to the theory that the protest movement represents a "lost generation" of unemployed or under-employed college graduates.

Konczal compares Occupy Wall Street to the protest movements of the pre-industrial era, in which landless peasants sought to expunge the debts they owed their masters. He writes: "The 99% looks too beaten down to demand anything as grand as 'fairness' in their distribution of the economy. There's no calls for some sort of post-industrial personal fulfillment in their labor—very few even invoke the idea that a job should 'mean something.' It's straight out of antiquity—free us from the bondage of our debts and give us a basic ability to survive."

That's an interesting theory. Before accepting it as gospel, I would need to see some more evidence, though. Statistically speaking, there may be a sample-selection problem. Are the profiles on We Are the 99 Percent representative of the Occupy Wall Street movement as a whole, especially now that it is spreading to other cities and encompassing other groups, such as union members? Unemployed twenty-six-year-olds with lots of student debt may have more time and motivation to post their profiles than active students and disillusioned fifty-year-olds who have been laid off.

But while we are playing this game, let me present my own pet theory. The most striking thing to me about Konczal's list of popular words is the absence of terms such as "Wall Street," "bonuses," "bailouts" and "CEO pay." None of them feature in the top twenty-five. This absence feeds my suspicion that Occupy Wall Street isn't primarily an anti-Wall Street phenomenon. It is a generalized anti status-quo protest movement, for which Wall Street serves as the convenient focal point.

If you accept this theory, it makes perfect sense that the protesters don't have short and snappy set of demands. They aren't sleeping under tarpaulins to support a financial-transactions tax, a return to Glass-Stegall, or a nationwide write-down in student loans, although some of them would support these proposals, to be sure. They are out there creating a ruckus because they think that things in this country are seriously out of whack, and have been for a number of years, with the politics and policies of both parties slanted scandalously towards the rich and powerful.

In this sense, the Occupy Wall Street movement is a left-wing version of the Tea Party: an inchoate and self-generated movement, which emerged from outside of, and in opposition to, the ossified political system. Wall Street provided it with its raison d'etre, but it is rapidly moving beyond its origins. In recent days, the protest has spread to many other cities across the country. If demonstrating against Wall Street was the be all and end all for the demonstrators, there wouldn't be much point in them camping out in Seattle's Westlake Park, for example. But for a more general protest movement, going nationwide is the next logical step.

October 10, 2011

Can Obama Win? Not This Way

With Chris Christie out of the race and Rick Perry struggling, the basic outlines of next year's election are emerging. It's going to be Obama versus Mitt Romney or A. N. Other (conservative), and the state of the economy will be the defining issue. Friday's announcement that employers created a hundred and three thousand jobs in September, and that the payroll figures for July and August were revised upwards by almost a hundred thousand, is modestly good news for the White House: fears of another downward lurch in G.D.P. and another big round of layoffs are receding.

But that doesn't mean that things are rosy for Obama—far from it. With the official unemployment rate seemingly stuck at nine per cent, and the unofficial rate, which includes people working part-time involuntarily and those too discouraged to look for employment, still above sixteen per cent, the question facing the President and his advisers remains the same: How do you win reëlection with mass unemployment, widespread alienation from the political process, and a large cadre of white working-class and middle-class voters who appear to have given up on the Democrats in general and Obama in particular?

According to a recent front-page Times story, Obama's Chicago brain trust has come up with an interesting answer: bypass some of the battleground industrial states, such as Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin, where disgruntled white men are ominously thick on the ground, in favor of traditionally Republican states like Colorado, Virginia, and Nevada, where an influx of urban professionals and Hispanics is helping the Democrats. Said David Axelrod, Obama's chief strategist: "There are a lot of ways for us to get to 270, and it's not just the traditional map."

Really, Axe?

Much as it makes a good story to suggest that Obama can ride back to the White House on the shoulders of a Frasier-J. Lo coalition, the electoral math simply doesn't add up—not yet anyway. One day in the not-too-distant future, a Democratic President may well be elected on the basis of largely bypassing the Midwest, but it won't be Obama.

To be sure, Axelrod and his colleagues can cite some impressive demographic trends to support their strategy. These developments go back to the late nineteen-eighties, when amidst the ruins of Michael Dukakis's campaign there were some hopeful signs for Democrats: the gradual move to the left by suburban states like California, Connecticut, and New Jersey; and the rise of the Hispanic vote in places like Florida and Arizona. In 2004, John Judis and Ruy Texeira took these trends and turned them into a provocative and well-researched book, "The Emerging Democratic Majority," in which they wrote: "We are witnessing the end of Republican Hegemony."

After Obama swept to victory in 2008, Judis and Texeira looked like geniuses. But an inspection of the electoral map suggested Obama's victory represented a more familiar phenomenon: a nationwide turn against an unpopular incumbent party. Yes, Obama picked up Colorado, Nevada, North Carolina, and Virginia—and impressive that was. But he also swept the Midwest, winning Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—states that, taken together, account for a hundred and eleven votes in the Electoral College. Colorado, Nevada, North Carolina, and Virginia account for just forty-three.

Making inroads among independents, college-educated yuppies, and minorities in fast-changing Republican states is all well and good for the Democrats. In the long term, it may well be fantastic. But to hold onto the White House next year, Obama also needs to win over, or hold onto, large numbers of more traditional Democrats—the so-called "Reagan Democrats," whose economic and cultural concerns were articulated by Stan Greenberg, one of President Clinton's pollsters, in his famous study of voters in Macomb County, Michigan (pdf).

If you doubt this, look at the latest 2012 electoral map from Real Clear Politics, which divides the states into five categories: Likely Obama, Leans to Obama, Toss-ups, Leans G.O.P.. and Likely G.O.P. To make things simpler, let's combine the "Likely" and "Leans" categories.

Likely Obama/Leaning Obama: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, Washington DC. Total electoral votes: 201.

Likely GOP/Leaning GOP: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, Wyoming. Total electoral votes: 191.

Toss-ups: Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Wisconsin. Total electoral votes: 146.

Now, let's try and usher Obama back to the White House on the basis of the Axelrod strategy. For this purpose, I'll assume the President fares poorly in the Midwest (setting aside his home state of Illinois), but pretty well elsewhere. So let's say he loses Ohio and Wisconsin, where he is polling poorly, but holds onto Virginia and North Carolina, two of his big wins in 2008. In terms of the Electoral College, these results offset each other: Ohio and Wisconsin together have 28 votes, and so do Virginia and North Carolina.

This gets Obama up to 229 votes, leaving him needing just 41 for victory, and it leaves the Republicans with 219. Now let's further assume that Hispanics in Las Vegas and yuppies in Boulder and Denver push the President across the line in Nevada and Colorado, snagging him 15 more Electoral College votes. Now, he's up to 244 and needs just another 26 for victory. Is he not home free?

If he were in better shape in Florida, which has 29 Electoral College votes, he would be. But the latest Quinnipiac poll shows that fifty-seven per cent of Floridians disapprove of the job Obama is doing, versus just thirty nine per cent who approve—the President's worst ranking in any state that Quinnipiac has surveyed. Some people I have spoken to say Florida is virtually a lost cause for the Democrats, especially if Senator Marco Rubio, the local Tea Party darling, is on the Republican ticket as a candidate for Vice-President. So, I'll give Florida 29 Electoral College votes to the Republicans, and citing history and Obama's poor poll ratings, I'll also add Iowa (6) and New Hampshire (4) to the G.O.P. column.

Obama now has 244 votes, and the G.O.P. candidate has 258. What states are left? Just two of them: Michigan, with 16 electoral votes, and Pennsylvania, with 20. In order to reach 270 votes, Obama has to win them both. (He also has to hold onto his home state of Illinois, where his approval rating has just dipped below fifty per cent.)

It's the same old story, with the election being decided in the big industrial states. Are there ways around this? Sure there are. But most of them depend on Obama turning things around in Florida, which seems unlikely. And recall, I'm also assuming here that Obama once again runs the table in Colorado, Nevada, North Carolina, and Virginia. That may happen, but I wouldn't wager heavily on it.

In closing, let me stress that none of this means Obama can't get reëlected. Depending on what happens to the economy, the outcome of the Republican primaries, and his own performance on the stump, he still has a decent shot at it. (Ladbrokes, the British bookmaker, make him the even money favorite to be the next President. Mitt Romney is the five-to-two second favorite.)

The point isn't that Obama won't win but that in order to do so he will have to follow the time-honored Democratic route of rampaging around the Great Lakes and squeezing home in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. It's also not as if he doesn't have anything to say to voters in these areas. With his rescue of the auto industry, he can claim to have saved many thousands of jobs in the Midwest, for example. But given his lowly poll ratings in many of these states, it's going to be a challenge.

Barack Obama speaks at a Democratic campaign fundraiser event in St. Louis, Missouri. Photograph by Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers