John Cassidy's Blog, page 109

November 21, 2011

The Super Committee and the Bond Market

There are two ways to figure out what is really happening in Washington politics. One is to interview Administration officials, congressmen, Capitol Hill staffers, think-tank wonks, and so on, and write down what they say. The other journalistic technique is to heed Deep Throat's immortal advice to Bob Woodward and follow the money trail. When it comes to budgets and the deficit, the Deep Throat methodology is usually the more informative.

Take today's flap over the congressional super committee and its failure to come up with an agreement to cut the deficit by $1.2 trillion, or more, over the next ten years. If you read the papers or watch the news, you might get the impression that this is big news. Busted deadlines on Capitol Hill; Senators Kerry, Kyl, and others making accusatory noises about the other side; red ink as far as the eye can see. All this sounds momentous and alarming.

But if you take Deep Throat's advice, things look rather different. Every day, when the global bond markets open, investors all over the world issue a judgment on the solvency and credibility of the Treasury Department. If something significant happens to impair that solvency and credibility, investors demand a higher interest rate to lend to the U.S. government, which is equivalent to saying that they offer lower prices for U.S. bonds. If something happens to boost investors' confidence in the U.S., then they are generally willing to lend us money at a slightly lower rate: bond prices rise and interest rates fall.

If bond-market investors had interpreted the demise of the super committee as truly shocking news, the bond market would have sold off badly this morning along with the stock market, which plunged more than three hundred points before recovering a bit. Instead of falling, the price of U.S. government bonds went up, and interest rates fell. Last Friday, the Treasury Department was paying an interest rate of 2.02 per cent on bonds due to mature in ten years time. This morning at eleven o'clock, the rate it was paying on equivalent securities had fallen to 1.95 per cent, which is extremely low by historical standards.

The insouciance of the bond market reflects a few things. First, bond markets often take a calmer view than stock markets, which tend to bounce up and down in reaction to news headlines. Second, the super committee's failure won't have much effect on the deficit. Crucially, the debt-ceiling agreement remains in place, and so do the two trillion dollars plus of budget cuts it entails. Doubtless, there will now be big battles about where the cuts should be distributed—John McCain and others are already trying to come up with a way to spare the Pentagon. But from a solvency perspective that is a secondary issue.

Third, the super committee's demise was hardly unexpected. Everybody knows that the two parties are hopelessly divided. With an election due within a year, it was never realistic to think that twelve senators and congressmen would succeed where the President and the Speaker of the House had failed. Earlier this month, Senator Chuck Schumer publicly predicted the committee would deadlock. Last week, there was a surge of optimism when Republican negotiators appeared to indicate a willingness to raise some real money in the form of new taxes. The optimism didn't last long. The actual figure that the Republicans were talking about turned out to be three billion dollars, which in the context of a $3.7 trillion budget isn't even chump change.

So where do we go from here?

For Democratic and Republican players alike in the budget game, the basic strategy now is to delay things until after next year's election, when both sides hope they will have more leverage. Back in the summer, when negotiators from the White House and the Republican leadership were working out the debt-ceiling deal, they were careful to make sure that the automatic spending cuts wouldn't go into effect until January 2013. The Bush tax cuts are due to expire on December 31, 2012. Thus, the stage is set for tax and spending issues to dominate the election campaign, which, one could argue, is only right and proper.

The only thing that could bring this long-running political game to a premature end is a dramatic sell-off in the bond market, which would raise the federal government's cost of borrowing, create problems for some big financial institutions, and quite possibly torpedo the dollar. For now, at least, such a dramatic turn of events looks unlikely—the main reason being what is happening in Europe.

Briefly put, global financial markets can only deal with one catastrophe at a time. From 2007 to 2009, investors were focussing on problems in the U.S. credit markets. Since 2010, the action has shifted to Europe. With bond yields surging in several European countries, and with liquidity drying up in some places, there is a real possibility of a Lehman-style systemic crisis erupting at any moment.

Even in a best-case scenario, the euro crisis won't be resolved for months. This means that investors who had been buying European bonds and other risky assets will need somewhere to park their cash—and that place is likely to be the U.S. bond market. For all the bipartisan squabbling and policy paralysis in Washington, assets backed by the might of the U.S. government are still viewed as a safe haven.

At some point, if the country continues down its current path, investors will lose faith in America, and all hell will ensue. But what the markets are telling us today is that, most likely, the Day of Judgment won't be until after next November.

Senate Minority Whip Jon Kyl of Arizona, left, and Sen. John Kerry, both members of the super committee. Photograph by J. Scott Applewhite/AP Photo.

November 18, 2011

Occupy at Two Months: Unions, Anarchists, and What's Next

When I got out of the subway at Washington Square on Thursday afternoon, there were sirens blaring, cop cars driving the wrong way down Sixth Avenue, and lots of people carrying signs and chanting. After gathering in Union Square as part of a "Day of Action" to mark the two-month anniversary of Occupy Wall Street, thousands of college students and union members were traipsing through the Village en route to Foley Square. Why they were going down Sixth Avenue rather than Fifth or Broadway, I have no idea, and neither did the cops. One of the marchers said it had been too chaotic on Broadway, so they had headed west.

The scene was noisy but good-humored. As the crowd moved south, cops ran alongside them shouting, "Stay on the sidewalk." Below Bleecker, some of the kitchen staff from Da Silvano came outside to see what the commotion was. At the corner of Spring Street, a young O.W.S.-type in a hoodie ignored the cops' orders and quickly found himself pressed against a catering truck with his wrists cuffed. "Shame, shame," other protestors shouted at the cops. As the cops put the kid in the back a squad car and drove him off, I thought back to the nineteen-nineties, when I lived in Soho for nearly ten years. In all that time, I don't think I spotted a single political protester. The only things I ever saw anybody getting arrested for were shoplifting and three-card monte.

The demonstrators moved on, turning left on Canal and right on Broadway. Seeing a tall, handsome guy with a black flag, black flowing hair, and two pretty young women accompanying him, I fell in behind him for a bit, thinking I might have happened across a latter-day Buenaventura Durruti. Near Walker Street, the anarchist's female followers abandoned him for Starbucks, leaving him to march on alone. At Foley Square, he disappeared into a huge crowd, which the N.Y.P.D. estimated at more than twenty thousand. I don't know where these figures come from, but the Square stretches for several blocks and it was packed to overflowing.

Up near the front, at the corner of Reade and Centre Streets, I came across a group of about twenty female health-care workers from Local 1199-S.E.I.U., who were standing beneath a banner that said "Jobs Not Cuts." They were jumping up and down singing: "Everywhere we go-o. People Want to Know-o. Who we are. Who we are. So we tell them. We are the union! We are the union!" Although most media reports focused on the sizable O.W.S. contingent, this was overwhelmingly a union crowd. There were public-school teachers, teamsters, transit employees, Verizon workers, CUNY staffers, and many others.

In New York, at least, it was support from unions that transformed Occupy Wall Street from a ragtag protest movement of activists, agitators, and students into something broader: an embryonic Tea Party of the left. When the mayor threatened to close Zuccotti Park one morning last month, many of the people who rushed down there to foil his efforts were union members. Now that Bloomberg has succeeded in his goal, the question of how to preserve and enlarge the protest movement looms large.

Many outsiders who sympathize with O.W.S. are secretly (and not-so-secretly) relieved that Bloomberg did what he did. With the camps gone, they argue, the movement can concentrate on more important things, such as campaigning for higher taxes on the rich and tougher financial reforms, and ensuring the reëlection of a Democratic President. Even Adbusters, the Canadian group that organized the original O.W.S. occupation, had appeared to advocate a strategy of declaring victory and going into hibernation for the winter.

Initially, I was thinking along similar lines. Now, I'm having some second thoughts. To be sure, there was something a little absurd about piling into a concrete plaza in lower Manhattan and expecting to stay there indefinitely. But the events unfolding in Zuccotti Park provided a focal point, real and symbolic, which supporters across the country could rally around and mimic. In a media-addled society that rarely focuses on one story for more than a few days, the occupation also provided an ongoing narrative that people could follow in real time. (Before setting out to yesterday's march, I spent a couple of hours watching it on a live-stream provided by "The Other 99.")

Last year, when Republicans in Congress were trying to torpedo the Volcker Rule, which placed tight limits on proprietary trading by big banks, I spoke with Barney Frank, who was then chairman of the House Financial Services Committee. This is what he said: Public opinion and the people can overcome the vested interests, but they have to be mobilized. If they aren't mobilized, the vested interests can win out.

However it happened—and I don't think even the organizers know the answer—the very act of occupying Zuccotti Park unleashed a nationwide political mobilization the likes of which hasn't been seen in a long time. If the encampments disappear and everybody goes home, how can this mobilization be sustained? And without the mass mobilization, what are the prospects of any real political change?

At about six o'clock, the protestors moved south towards City Hall and the Brooklyn Bridge, which they were intending to walk across (on the footpath). It was cold and dark, and a few young agitators near me were baiting the cops, unhinging the barricades they had set up and knocking them over. After the violent clashes earlier in the day, near Wall Street, I thought more trouble might brewing, but it didn't materialize. The cops kept their cool, and the troublemakers got swept along in the huge, peaceful crowd, which was chanting, over and over again: "All day, all week: Occupy Wall Street."

Photograph by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

November 17, 2011

Obama and Zuccotti Park: What He Didn't Say

Unlike many of my friends and acquaintances, I don't feel particularly let down or cheated by Barack Obama. Back in 2008, I viewed him not as a transformative political figure but as a moderate, talented young Democrat, whose speaking skills and keen intelligence partly made up for his lack of experience. In a classic "time for a change" election, he was the right man in the right place.

As President, I think Obama has done a fairly decent job of cleaning up the financial mess he inherited, keeping the economy afloat, and restoring America's reputation in the world. I say "fairly decent." A bang-up job would have featured pushing through a bigger stimulus; imposing harsher terms on bailed out banks; passing a broader "Volcker Rule" with the intent of breaking up financial behemoths; and making a decisive effort to resolve the housing crisis. But none of these things was a cinch. Presented with a trillion-dollar-plus stimulus, Congress may well have balked. The Bush Administration had already dictated the terms of the bailouts. A narrow "Volcker Rule" barely squeezed through Capitol Hill. And bailing out underwater homeowners on the scale necessary to raise house prices would have been a huge logistical and political challenge.

In the nineteen-thirties, of course, F.D.R. rose to such challenges and triumphed. Obama, a habitual seeker of the center ground with little experience of running anything and a shaky majority in the Senate, was never going to morph into Roosevelt. Hopes to the contrary were daft. But every now and again, and despite my modest expectations, he does manage to disappoint me—even when he is on the other side of the world.

On Tuesday afternoon, this Associated Press headline crossed the wires: "Obama: Cities Must Make Own Decisions on Protests." About twelve hours earlier, in the dead of night, hundreds of cops in riot gear had cordoned off much of lower Manhattan, cleared out Zuccotti Park, and arrested some two hundred people, including journalists and a City Councilman. (My colleague Philip Gourevitch has written more on the paramilitary aspect of the operation.) This is what the AP story said:

ABOARD AIR FORCE ONE (AP) — President Barack Obama's spokesman is suggesting the president believes it's up to New York and other municipalities to decide how much force to use in dealing with Occupy Wall Street demonstrations.

Spokesman Jay Carney also says Obama hopes the right balance can be reached between protecting freedom of assembly and speech with the need to uphold order and safeguard public health and safety.

Carney spoke to reporters Tuesday as Obama flew to Australia. He was asked whether Obama had been following the early-morning police raid on Zuccotti Park in New York, where Occupy Wall Street protesters have camped out for weeks.

Carney said the president was "aware of it."

To begin with an obvious point: if Obama had wanted to comment on the breaking up of a protest that has drawn worldwide attention (and why wouldn't he?), then rather than dispatching Carney with the message, he could have ambled back to the pool reporters who fly in the rear of Air Force One. And what might he have said? How about something like this:

Hi everybody. Before we arrive, I just wanted to say that I saw what happened in New York this morning and give you my reaction. As I said shortly after the Occupy Wall Street protest began, I think it expresses the frustrations that many ordinary Americans feel. The demonstrators in New York and other cities are giving voice to a broad-based anger and frustration. We had the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, with huge collateral damage throughout the country, and yet some of the same folks who acted irresponsibly are still fighting efforts to crack down on abusive practices that got us into this mess in the first place.

Second, I think the protestors have performed a valuable public service by raising two issues we have neglected for too long: the sharp rise in income and wealth inequality, and the corrosive role that money plays in American politics. When the protestors say that rich people need to pay their fair share of taxes, and that we in Washington often pay too much attention to the wishes of Wall Street and other powerful interest groups, and too little attention to the interests of middle-class families, they are only stating what most Americans know to be true. Indeed, the money problem is getting worse. Under a recent ruling from the Supreme Court, corporations and billionaires can make unlimited contributions to political parties. Some of them, as you know, are already financing ads aimed at me and my policies.

Third, as a former lecturer on Constitutional Law, I have a great appreciation for the rights afforded Americans under the First Amendment, which includes freedom of speech and freedom of expression, but also the right to peaceably assemble. Now, according to all the reports I have received, almost all of the folks associated with Occupy Wall Street have behaved peacefully. In a protest movement that has spread to more than a thousand locations across the country, there have been remarkably few reports of violence. Conservative efforts to portray the protestors as anti-American agitators and troublemakers are misplaced.

All that said, the cities and localities in which the protestors have gathered do have an obligation to uphold order and to safeguard public health and safety. If the demonstrator's encampments present a genuine fire threat or health threat, they must be cleaned up. If and when people break laws, including the law of trespass, the authorities must put a stop to it. But I call upon mayors, governors, and local police chiefs—whether they are Democrats, Republicans, or independents—to exercise caution in how they act, and to treat the demonstrators with the respect that all law-abiding citizens deserve. Because, to an overwhelming extent, that is who the protestors are: patriotic citizens, concerned about their country, who are exercising their rights under the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. I commend Mayor Bloomberg for re-opening Zuccotti Park to them.

For people in authority, dealing with such folks can be costly, time-consuming, and irritating. Trust me: having spent almost three years dealing with members U.S. Congress who are exercising their constitutional rights to block many of my policies, I know what I am talking about. But public participation and occasional frustration on the part of the rulers are integral to our democracy. We all like to see our country as a nation of laws, a nation of due process, a nation—as the Constitution puts it—of inalienable rights. If we don't take these things seriously, if we exercise authority in arbitrary and excessive ways, then we are undermining the things we were elected to defend.

I am not saying that New York or any other cities have stepped over this line. In some cases, the local authorities have acted with admirable restraint; in others, they appear to have used a considerable amount of force. Without detailed information about what was happening on the ground, I would not pre-judge any particular decision or action. My point, rather, is that there is a line we need to keep our eyes on, and to cross at our peril.

That's it. Thanks a lot everybody. Now I am going back to my cabin to read some briefing papers and watch a tape of Tiger Woods playing golf in Australia. See you all later.

Would such a statement have made a big difference to the future of Occupy Wall Street, or to next year's election? Probably not. Would it have sent an important message to cities and states that they don't have carte blanche in dealing with protestors? Would it have conveyed something significant about the President's values? And would it have cheered up his supporters? Surely, it would have done all of these things.

Photograph by Donald Traill/AP Photo.

November 16, 2011

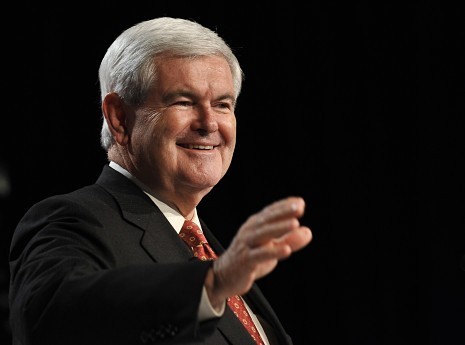

Campaign Memo: The Newt Express

No reply yet from Newt Gingrich to my love bomb of a couple of days ago, but, hey, no hard feelings. Now that Newt's a serious Presidential candidate, he has more important stuff to do than swap mash notes—such as trekking around Iowa and dealing with scurrilous gossip put out by rival campaigns, political enemies, and misguided reporters.

Take the ludicrous suggestion that Freddie Mac, the smaller of the two government-sponsored mortgage giants, may have expected Newt to do some lobbying on its behalf when, in 2006, it paid him the very modest sum of $300,000. Any fair-minded person would agree that Newt quashed this idea during one of last week's debates. He explained that Freddie's executives hired him for his expertise as a historian, adding that he warned them to stop lending money to folks who couldn't repay their loans. In Newt's own words: "My advice as a historian, when they walked in and said to me, 'We are now making loans to people who have no credit history and have no record of paying back anything, but that's what the government wants us to do.' As I said to them at the time, this is a bubble. This is insane. This is impossible."

That explanation was more than good enough for me. But darn it if a couple of quibbling scribblers from Bloomberg News didn't put out a report yesterday, quoting former executives of Freddie Mac saying that Newt was hired "to build bridges to Capitol Hill Republicans and develop an argument on behalf of the company's public-private structure that would resonate with conservatives seeking to dismantle it." According to this non-story, Newt attended brainstorming sessions with Freddie's top brass about how Freddie Mac could gain more political support on Capitol Hill, and, in February, 2007, he visited the company's headquarters and spoke to forty or fifty of the firm's employees about the Presidential campaign. The article went on: "None of the former Freddie Mac officials who spoke on condition of anonymity said Gingrich raised the issue of the housing bubble or was critical of Freddie Mac's business model."

What is it about Newt's explanation that his critics don't get?

The folks peddling this lobbying garbage—today Bloomberg has another story, which says that Freddie Mac paid Newt a total of $1.6 million over the years—are probably the same people who are re-circulating a video of Newt's speeches in 2007, when he referred to Spanish as the language of the "ghetto." It's not as if Newt hasn't apologized for giving offense where none was intended: he has. He's even started to tweet in Spanish. But did he even need to say sorry? His use of the word "ghetto" ought to be placed in the proper context. What he actually said was this: "The American people believe English should be the official language of the government. We should replace bilingual education with immersion in English, so people learn the language of prosperity, rather than the language of living in a ghetto." How could anybody take offense at that?

As for the renewed gossip about Newt's private life, I hesitate to dignify it by even bringing it up. But one ridiculous story has to be addressed, because it has already appeared in a book. That's the claim that Newt purchased more than a million dollars in jewelry from Tiffany's to "pay off" his third wife, Callista, so she wouldn't object to his running for President. Tom Bevan and Carl Cannon, the two reporters from Real Clear Politics who make this allegation in their new e-book, "Election 2012: The Battle Begins," quote an unnamed campaign strategist who told them that Callista was "the single worst influence on a candidate I've ever seen."

Where do these bozos get off? Anybody who was in Webster City, Iowa, on Tuesday afternoon to see the fragrant Mrs. Gingrich speaking to G.O.P. supporters about American exceptionalism, could see instantly that she didn't need any inducement to support her husband's campaign to save us all from a threat worse than smallpox: i.e. "Obama's Secular-Socialist Machine." My goodness, this talented woman has just published a book that is devoted to the same noble cause her husband is pursuing. Entitled "Sweet Land of Liberty," it aims to teach four-to-eight year olds about the great events in American history through the eyes of Ellis the Elephant, her very own literary creation. If that's not the stuff of a future First Lady, I don't know what is.

Let's get real. This new round of baseless attacks on Newt is intended to diminish his appeal to ordinary patriotic Americans. But guess what: it isn't working. The Wall Street Journal, which is what I call a respectable newspaper, has a story today about how his campaign is building momentum in Iowa. And a new national poll from McClatchy/Marist shows Newt in a statistical tie with Obama. In a head-to-head matchup with the President, he's doing better than Cain, better than Perry and Paul. He's even doing better than Romney.

Take that, Paul Begala, and all the rest of you carpers and doubters. The Newt Express is rolling, and it isn't going to stop until January, 2013, when it pulls into Union Station, Washington, D.C. Rather than trying to place rocks in its path or sabotage the signal box, why not hop aboard?

Photograph by Nicholas Kamm/AFP/Getty Images.

November 15, 2011

After Zuccotti: What Now for Occupy Wall Street?

Almost two months to the day since anti-Wall Street protesters occupied Zuccotti Park, Mike Bloomberg finally did what he's clearly been aching to do all along: cleared them the heck out of there. Perhaps encouraged by similar actions in Oakland and Portland, the Mayor unleashed the N.Y.P.D.'s riot squad in the dead of night, first taking care to cordon off the area from prying news cameras.

As the sun came on yet another balmy mid-November day, two questions arose: Were the protesters gone for keeps? And where would the Occupy Wall Street movement go from here?

As of noon, the first question was shrouded in confusion. A few hours earlier, responding to a request from the National Lawyers Guild, Justice Lucy Billings, who sits on the State Supreme Court, had issued a temporary restraining order preventing the city from enforcing park rules, such as "no tents," on the protesters, and ordering the city, the Mayor, the police department, and Brookfield Properties to show cause for their actions. Of course, the N.Y.P.D. had already enforced these rules, as evidenced by this A.P. footage, which shows sanitation workers filling garbage trucks with tents, tarps, and other detritus from the encampment.

Justice Billings set a hearing for later in the day, and Mayor Bloomberg, speaking at a press conference in which he attempted to justify his actions by saying the protesters had deprived other New Yorkers of the right to use the park and created a health hazard, said the city would fight her restraining order. A few dozen protesters were allowed back into the park, minus tents, only to be turfed out again pending the court hearing. Meanwhile, other protesters had marched uptown and occupied a lot at Canal and Sixth Avenue that is owned by Trinity Church.

The larger question, about the future of Occupy Wall Street, won't be answered today or tomorrow. If the Mayor and the editorial page of the New York Post think the protests will simply fade away, they are deluded. In its short life, O.W.S. has gone from a local sideshow to a national movement, with offshoots in hundreds of towns and cities. Whatever happens next, it has already changed the terms of the political debate, putting rising inequality front and center, which is where it should have been for years.

Still, O.W.S. has to make some decisions about its future. At its heart, there has always been an incipient tension between aims (reducing inequality and reinvigorating an ossified political system) and means (occupying urban real estate). Now that its encampments in many cities have been broken up, and with winter coming on, the movement needs to confront this tension and, if not resolve it, at least come up with a way to negotiate it over the next few months.

Some opportunistic outsiders, such as Jeffrey Sachs, the director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, are keen to seize upon O.W.S. as a vehicle to create a new progressive movement, with its own political candidates and party platform. In a widely circulated piece in Sunday's Times, Sachs argued that the success of O.W.S. heralds a sea change in American politics. "A new generation of leaders is just getting started," Sachs wrote. "The new progressive age has begun." Sachs even suggested a snappy platform: "Tax the rich, end the wars and restore honest and effective government for all."

If only it were that easy to transform American politics. As anybody knows who has spent time in Zuccotti Park and sat through one of the "General Assemblies," it is tough for the organizers of the protest to get anything done, let alone set up a new political party. With unanimous support required for new initiatives or significant expenditures, some recent assemblies have degenerated into shouting matches, and last week a dissident group set up its own alternative assembly.

Given the internal fissures that were developing, it could conceivably turn out that Bloomberg has done O.W.S. a favor. In some ways, the movement has already outgrown Zuccotti Park. It now has more than eighty working groups, looking at everything from community banking to town planning. It has significant media support. It has ties to trades unions, environmental activists, and the backing of celebrities and public intellectuals, such as Sachs and his colleague Joseph Stiglitz.

What is needed is some way to build upon these successes while maintaining the energy and enthusiasm that O.W.S. has unleashed. The recent history of the "Indignants" in Spain shows that a heterogeneous protest movement can survive the loss of its focal point. In June, after repeated clashes with the police, the Spanish protesters decided to leave their encampment in Madrid's Puerta del Sol. The movement lives on: last month, hundreds of thousands of people marched in its support through Madrid, Barcelona, and other cities.

Can O.W.S. make a similar transition? I hope so.

November 14, 2011

The Newt Surge: Every Dog Has Its Day—Even the Dead Ones

Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living.

—Karl Marx

Three months ago, Newt Gingrich looked like roadkill. Most of his campaign staff had quit, his money had run out, and his poll ratings were in the low single digits. When the conservative National Review polled its readers on whether he deserved a second look, the vast majority said no.

Now the Mouth of the South is back: climbing in the polls, raising money at a much faster rate than he had previously, and, strangest of all to behold, attracting praise from mainstream pundits. "My debate grades: Gingrich A-; Perry B+; Romney B+; Huntsman B; Bachmann B-; Santorum C+; Paul C; Cain C-," Mark Halperin, of Time magazine, tweeted on Saturday night following the CBS/National Journal debate on foreign policy. Even before the debate, in which he joined Mitt Romney and Michele Bachmann in endorsing military action to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons, Gingrich was on something of a roll. Two national polls released on Friday, one from CBS the other from McClatchy, both placed him in second place. (In the CBS poll (pdf), Herman Cain was leading; in the McClatchy survey (pdf), Mitt Romney was ahead.) Gingrich's numbers are also rising in Iowa, South Carolina, and Florida, where three of the first four primaries will be held. At the National Review and other places where right-thinkers gather, Gingrich is now taken seriously again: "I wouldn't be surprised if he's leading polls in a week or two," Rich Lowry, the longtime editor of the magazine, wrote a few days ago.

So what explains the turnaround? In a column for Politico yesterday, Jeff Greenfield, the veteran political analyst who now co-hosts "Need to Know," a newsmagazine on PBS, gave much of the credit to the candidate himself, writing,

As Gingrich has done in just about every debate, again and again Saturday he was operating at a level of tactical and strategic skill far above his opponents. His eye for the mot juste, for the jab or counter-punch that will please his audience, is unparalleled. Whatever his liabilities as a prospective nominee—and they are legion—Gingrich has climbed back from irrelevancy to contender because he is playing Assassin's Creed Revelations while his opponents are playing Pong.

That's one theory, and there's something to it. As Greenfield points out, Gingrich is expert at sending coded messages to right-wing groups others neglect: the U.N. bashers; the Fed bashers; evangelicals worried about attacks on Christians in Egypt. During last week's CNBC debate, he even got in a shot at Saul Alinsky, the radical community organizer who died in 1972.

But Gingrich has done this sort of thing all along. Even at his lowest point, in July and August, he never stopped bashing the U.N.-Obama-Pelosi axis, his own version of the Trilateral Commission, and spouting off about his pet theories of everything from health-care reform to military strategy to the Constitution. Over the weekend, I met a woman who said she encountered Gingrich not too long ago at a reception in Hong Kong. What was he doing?, I asked. He was surrounded by a group of people, and he was delivering a peroration on ancient Greek history, she replied. Of course he was. Say what you like about Newt, he's always been a world-class gasbag.

As a political candidate, on the other hand, he is the same combustible, dislikeable, self-regarding train-wreck-waiting-to-happen that he's always been. The truth is, his rebound has almost nothing to do with him and almost everything to do with circumstances beyond his control.

As a former assistant professor of history at West Georgia College, and a self-described expert on socialism, Gingrich is doubtless familiar with the quote above from Karl Marx, which comes from "The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte." Contrary to some accounts, Marx wasn't a crude economic determinist: he believed in the role of the individual, while pointing out, perfectly correctly, that larger forces, and prior history, determine the scope for individual action.

Since Marx's time, of course, history has speeded up remorselessly, to the point where in the Republican primary each generation of conservative leadership lasts about a month. In August the new Messiah was Bachmann; in September it was Perry; in October it was Cain. Had any of these folks turned to be serious candidates, Newt would still be on his book tour. Their demise created a huge vacuum that somebody had to fill, and, with more plausible figures such as Jeb Bush and Mitch Daniels still refusing to leap in, Gingrich has become the conservative candidate by default.

The probability of him winning the nomination is small. Intrade, the political betting market, currently puts it at 11.6 per cent, which sounds about right. (Romney's odds of winning are 71.3 per cent.) But that doesn't mean he can't mount a semi-serious challenge and makes things interesting. Setting aside the chronic weakness of his conservative opposition, two things are working in his favor.

One is the mood of the country, which mirrors Gingrich's sourpuss character. According to a new poll of voters in marginal states, from Politico and George Washington University, three in four Americans believe the country is "somewhat" or "strongly" on the wrong track—comfortably the highest figure in the poll's history—and two in three don't believe the next generation will be better off economically than the current generation. Romney and others will be competing with Gingrich to blame the President and congressional Democrats for this predicament, but on this subject Gingrich is a step ahead. For a year and a half, he has been rattling on about the threats to America's soul presented by Obama's "secular socialist machine," which just happens to be the subtitle of his latest book.

Then there is the media, which Gingrich likes to berate at every opportunity. In this instance, for once, his interests and those of his media enemies are perfectly aligned. With ten months to go until the Republican National Convention in Tampa, the last thing anybody who is reporting on the campaign wants is a Romney rout. If the Republican front-runner were to sweep Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Florida with large margins, the whole thing could be more or less wrapped up by the end of January.

To prevent that from happening, you can expect in the coming weeks to read a lot more about Gingrich and his proposals, and you can also expect more assessments like this, from Jeff Greenfield: "Judged simply by the measure of political success, Gingrich has already wrapped up the Performer of the Year award."

Welcome back, Newt. As a paid-up member of the campaign scrum, I, too, am glad that you will be around for a while to give Romney fits. Just don't mind if I turn the sound down every now and again when you appear onscreen, and don't ask me about your leadership skills. Unlike Rick Perry, I have the darndest time forgetting things, such as your statement to Time magazine in December, 1994, when you and your colleagues had just taken control of Congress: "I think we'll have a good run. My guess is it will last 30 or 40 years." Within eighteen months, Gingrich had shut down the federal government, resurrected Bill Clinton's Presidency, been engulfed by scandal, and seen his colleagues plotting to get rid of him.

Let us end as we began, with another crotchety and long-winded ideologue. "Hegel remarks somewhere," Marx wrote in the first line of "18th Brumaire," "that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce."

Photograph by Alex Wong/Getty Images.

November 11, 2011

Obama's Mini-Surge

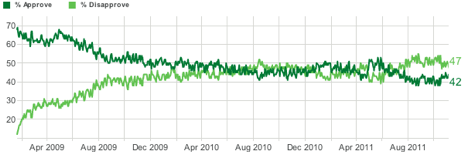

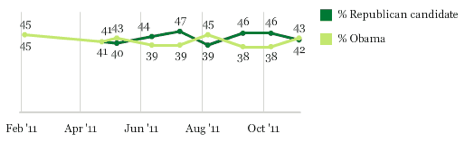

With all the weird stuff going on in the Republican race, another important story, perhaps related, has been underreported. President Obama is enjoying something of a political renaissance. His approval rating, after diving during the debt-ceiling crisis, has rebounded somewhat. Independents, in particular, seem to be rethinking their opinions of him, and in head-to-head surveys he is now leading or running equal with a generic Republican candidate.

The President's position is still by no means enviable, and his recent revival may not last. Much depends on the economy and the next round of budget negotiations, which will come to a head later this month. But fears that Obama was turning into another Jimmy Carter appear to have been misplaced. All indications are that next year's election is going to be close, with the result hinging on what happens in a handful of states. And in those states, Obama is looking much more competitive than he did a few months ago.

Here is the latest polling data, which is delivering a pretty consistent message:

1. Approval ratings. The daily Gallup tracking poll. Because the daily numbers bounce around, political professionals look at the three-day average. Three months ago (August 11-13), just 39 per cent of Americans approved of Obama's job performance and 54 per cent disapproved. The latest figures (November 7-9) show his approval rating has risen to 42 per cent and his disapproval rating has fallen to 47 per cent. To be sure, that still isn't great. The White House would much prefer to see the approval rating higher than the disapproval rating, but since August the negative balance has fallen from fifteen points to five.

2. Head-to-head polls. On a monthly basis, Gallup asks voters how they would vote in a contest between the President and a generic (unnamed) Republican candidate. In August and September, Obama was trailing the generic Republican by eight points (38 per cent to 46 per cent). In Gallup's latest survey, which was published yesterday, he is back to even: Obama 43 per cent, Republican 42 per cent. (Statistically speaking, this is a tie.) These figures are for voters with firm preferences. When Gallup also counted undecided voters who are leaning one way or another, it found Obama with a bigger lead—48 per cent to 45 per cent—albeit one that was still within the margin of error.

3. Independents. Obama's rebound has been particularly noticeable among voters who identify themselves as independents. The conventional wisdom is that this is where elections are decided. In September, Gallup found that among independents Obama was trailing the generic Republican candidate by 27 per cent to 48 per cent—a massive gap. In the new poll, he has pulled back to even. Both he and the generic Republican get 38 per cent of the independent vote.

4. Battleground states. The President's strategists continue to insist that there are many ways to accumulate 270 votes in the electoral college. (Ryan Lizza has a post today looking at a couple of possible strategies.) As I've said before, I don't take this very seriously. Neither do the pollsters. Yesterday, Quinnipiac University's polling institute released its Swing State Poll of voters in Florida, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. Since 1960, nobody has won the Presidency without winning at least two of these three states. In the new poll, Obama's approval rating in the battleground states is very similar to his rating nationally: 41 per cent in Florida; 44 per cent in Ohio and Pennsylvania. No great shock there. But the poll also shows that in head-to-head contests Obama has a handy leads over all of the individual Republican candidates, except for Romney, whom he is running roughly even with. In Ohio, Obama leads Romney by 45 per cent to 42 per cent; in Pennsylvania, he leads by 43 per cent to 42 per cent; in Florida, he trails by 42 per cent to 45 per cent. Statistically, these races are all ties.

Coming on top of Tuesday's actual voting across the country, which produced a number of setbacks for Republicans, these polls suggest that, with about a year to go until the election, all is still to play for. Obama isn't exactly popular, but neither are the Republicans. "Dissatisfaction with the President as evidenced by his mid-40s percent job approval and weak 'deserves a second term' ratings hasn't translated into affection for his GOP challengers," said Peter A. Brown, of the Quinnipiac polling institute. That couldn't be described as a ringing endorsement of Obama, but it suggests he is still very much alive. After what he went through in August and September, he and his staff will see reasons for cautious optimism.

Photograph by Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images.

November 10, 2011

Pop Goes Perry; Mitt Marches On

With Europe in chaos, Wall Street having another conniption, and global capitalism again on the brink, light relief is badly needed. Once more, last night, the Republican Presidential candidates didn't let us down.

To begin with, of course, there was Rick Perry's mental blackout, the tape of which you will most certainly have seen. (Just in case you've been held in solitary confinement and deprived of television and the Internet for the last however many hours, it is above.) But that was more snuff video than comedic entertainment. Wracking my brain to come up with similarly excruciating moments, I thought back to 1992, when Vice Admiral James Stockdale, Ross Perot's running mate, struggled with his hearing aid and lost his train of thought during a Vice-Presidential debate with Al Gore and Dan Quayle. But when I went to YouTube and re-watched those incidents for the first time in many years, they didn't look nearly as bad as Perry's gaffe.

As the Texas governor stood there abjectly, trying to recall the third federal agency he would shutter in addition to the Departments of Commerce and Education, I actually turned away from the screen, begging for somebody to put him out of his misery. Eventually, Mitt Romney, who at one point in the distant past (September) must have considered Perry a serious rival, displayed his charitable side and said "E.P.A." Unfortunately for Perry, that was the wrong agency. ("Energy" was the word he was searching for.) It was left to John Harwood, the CNBC co-host, to administer the fatal dose. "You can't name the third one," he asked. Perry looked down at some notes but still couldn't answer. "I can't, sorry," he said. A ghastly smiled crossed his face. "Oops," he whispered.

Until Perry's demise, which came about ninety minutes in, there hadn't been anything very newsworthy. Since his candidacy had already turned into a running joke, you could argue there wasn't anything very newsworthy even then. But before we all forget about him and consign him to history, I have one request: Can somebody in authority please appoint a bipartisan commission, or send a team of investigative reporters, to find out how this buffoon became the governor of the country's second largest state by population and area? In Texas, they do a lot of things differently, I realize. But come on. Surely there were alternative choices.

Perry apart, perhaps the biggest news items were Herman Cain referring to Nancy Pelosi as "Princess Nancy" (good idea, Herman: offend some more women); Romney vowing not to bail out Italy and the rest of Europe (you went out on a ledge there, Mitt); and C-Span 2 pledging to run all seven three-hour Lincoln-Douglas-style Presidential debates if Newt Gingrich somehow captures the nomination. You are right: I am kidding about the last one. Not even C-Span 2 would subject their viewers to twenty-one hours of Gingrich hectoring and pontificating. After he had acted patronizingly towards Maria Bartiromo for perhaps the third or fourth time, I thought she might walk across the stage and crown him. If she had, my wife would have cheered. "I hate Gingrich even more than Cain," she shrieked before I asked her to leave the room on the grounds that she was threatening my objectivity.

Rededicated to the values of the Columbia School of Journalism, I tried to find something non-negative to say about the other candidates. Michele Bachmann talked about the payroll tax cut blowing a hole in the Social Security trust fund and criticized Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for paying twelve million dollars in bonuses to their top ten executives. However, she then stepped on the suggestion that her mind extends beyond campaign bullet points by rattling on about repealing Obamacare and building a fence on the southern border. Rick Santorum told us that he was the one who came up with many of his opponents' proposals—health-savings accounts, returning Medicaid to the states, and so on. Ron Paul said he would shut down the Fed. (No, that wasn't a sensible suggestion, but it did indicate consistency on Paul's part. He's been saying the same thing for years.)

Just when you were thinking things couldn't get stranger, Jim Cramer reappeared, looking even more amped than usual. During his first stint at the questioners' table, he had pleaded with the candidates to consider a bailout Italy for the sake of the stock market, the banks, and people's 401k's, only to evince from Paul the Andrew Mellonesque response: "You have to let it liquidate." Second time up, Cramer asked Cain what could be done to restore ordinary investors' trust in a market dominated by hedge funds and high-speed traders. "Jim, I feel your pain," quipped Cain, before demonstrating he had no idea whatsoever how to answer the question.

And so it went on, with Romney deftly avoiding commenting on Cain's problems or anything else that might rebound on him, while bravely taking potshots at people who don't vote in the Republican primaries. His targets included President Obama, whom he described as somebody "driven by one thing: his reëlection," and the members of the Chinese government, which he said was "cheating" and "killing jobs in America." Jon Huntsman calmly pointed out that Romney's plan to designate China as a currency manipulator would only prompt Beijing to give the same designation to the United States on the grounds that the Fed's policy of quantitative easing is a backdoor way of devaluing the dollar. This was accurate and insightful, as is much else that Huntsman says, not that anybody takes any notice. He has about as much chance of winning the nomination as Perry has. His only role in these proceedings is to rehearse some of the arguments that President Obama will use against Romney next year.

But you are assuming the primary contest is already over, I hear you object.

Too right, I am. Unless somebody new enters the race in the next few weeks—and it would have to be a far more plausible candidate than Perry, Cain, or Gingrich—Romney is a racing certainty. Call him a flip-flopper. Call him a panderer. Call him a Wall Street robber baron. He is all of these things. And compared to these opponents (Huntsman aside) he looks like Washington or Jefferson.

The biggest threat to Romney, I think, is his hair. Tonight, it was distinctly unruly. Rather than staying in the slicked-back military formation that makes him resemble a shirt model, or a character on "Mad Men," it flopped about a bit. Some strands even ventured down his forehead, which is strictly verboten. Before he flies down to South Carolina for the next Republican debate (yes there are more of these, many more) he will have to get a team of young Bainies to run some numbers on where his hairdresser and make-up people went wrong. In the Romney campaign, there is no room for error, or even the possibility of error. After all, and appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, running for President is a serious business.

November 9, 2011

Keynes vs. Hayek: Debate Diary

Tuesday evening. To the Asia Society on Park Avenue, where I am taking place in a Keynes vs. Hayek debate organized by Sir Harold Evans and Thomson Reuters. (At some point today, you will be able to watch it.) Representing J.M.K.: James Galbraith (University of Texas), Steven Rattner (Wall Street/Obama Administration), Sylvia Nasar (Columbia; author of "Grand Pursuit," a new popular history of economics), and myself. Representing F.V.H.: Edmund Phelps (Columbia), Lawrence White (N.Y.U.), Diana Furchtgott-Roth (Manhattan Institute/Bush Administration), and Stephen Moore (Wall Street Journal).

Decent crowd in attendance—couple of hundred or so. Sir H., a sprightly Mancunian lad of eighty-three, gets things going in his usual engaging manner. ("Sir Harold Evans for President" tweets Kelly Evans, of the Wall Street Journal.) The motion reads, "In these perilous times, do we listen to John Maynard Keynes or his arch critic, Friedrich Von Hayek?" Before calling on the speakers, Sir H. asks the audience to vote using some electronic doo-dahs in their seats. He doesn't reveal the results.

First up for our side is Galbraith fils, a hefty fellow who clearly enjoys a good intellectual brawl. He quotes liberally from Keynes, which is always fun, while pointing out that Hayek's macroeconomic theories were dismissed by, amongst others, Milton Friedman. Toward the end, he cleverly slips in a jab at the banks, which is a good tactic pretty much anywhere these days: "Keynes in 1930 knew what Occupy Wall Street tells us today: the Great Depression was produced by banks."

Leading off for the Hayekians, Ned Phelps, the recipient of a Nobel in 2006, says that despite nine per cent unemployment there is no shortfall of demand in the economy. Did he really say that? Yes he did. I write it down in red ink: "We do not have a deficiency of demand." The problem is "structural," Phelps goes on, and Keynesian economics has nothing to say about structural slumps. As one of the people who came up with the concept of a "natural rate of unemployment," Phelps knows whereof he speaks. But does he really think the N.R.U. is nine per cent? Evidently, he does. Wow!

Now it's my turn. I have six points but only four minutes to make them in. I manage to get through three: 1) Hayek was a very important thinker, but his major contribution was to the debate about socialist planning versus the free market. (For more on this, see my 2000 article about Hayek, "The Price Prophet.") On the subject of the debate—how to drag economies out of deep recessions—Hayek had little to say. Keynes and his followers roughed him up so badly that he gave up the fight, not even bothering to review "The General Theory." 3) In a crisis, we are all Keynesians—from Ronald Reagan to George W. Bush to Paul Ryan. The only debate is whether to cut taxes or increase government spending.

Stephen Moore comes next, delivering a predictable tirade about the Obama stimulus and how hopeless it has proved. About the only good thing that has come out of the past four years, Moore says, is the discrediting of Keynesian economics. We have spent four trillion dollars and got nothing in return. "What would have been better for our economy, all this stupid spending or four years of no income tax?" In a one-minute rebuttal, I ask Moore where he got the four trillion dollar figure from—the actual figure is about eight hundred billion dollars—and point out that one reason the recovery has been so slow was because the federal stimulus was offset by fiscal contraction at the state and local level. Moore isn't placated, of course. I don't know whether he has ever read "The General Theory," but he can flog Obama and the Democrats in his sleep.

With my turn done, I slump in my seat and glance around the audience, which largely consists of men in jackets and ties. Bit ominous for our side: more Wall Street than Occupy Wall Street. Meanwhile, Nasar and Furchtgott-Roth are talking at cross-purposes, which is par for the course in this sort of thing. Nasar is making a historical point about the differences between Keynes and Hayek on monetary policy. Furchtgott-Roth, a formidable woman who has a bit of Mrs. Thatcher about her, is banging on about the deficit and the need to slash spending.

I perk up a bit when Steve Rattner delivers a spirited defense of the auto bailout, which was started under Bush and completed under Obama. In 2009, Rattner served as the Treasury Department's "car czar," overseeing the task force that orchestrated the successful rescue of General Motors and Chrysler. Markets often work, he says, but sometimes they fail, and when that happens it is the government's job to step in. That argument sounds familiar. Has Steve been reading my latest book, I wonder? Probably not. What he is saying is common sense, accepted by everybody except a few free market ultras.

Up steps Lawrence White, of N.Y.U. Years ago, I attended some lectures on the Austrian approach to economics delivered by his former colleague Israel Kirzner, who has since retired. White gives a good account of himself, getting in jabs at Steve for bucking the market and me for failing to read all of "Prices and Production," Hayek's 1931 tract. But then he says that Hayek would have supported a nominal G.D.P. target for monetary policy, and that this alone would solve our ills. Really? The Fed already has a nominal anchor—an informal inflation target of just below two per cent. It hasn't helped it navigate a liquidity trap. Of course, White probably doesn't believe in those either.

Now it's time for questions from the audience. Suddenly, it seems as if Ayn Rand's Collective and the Von Mises Society have been bused in. Wasn't the housing bust all the fault of Fannie and Freddie and the Community Reinvestment Act? What is capital? Is there any level of debts that Keynesians won't accept? I try to point out that Keynes was no prodigal. During good times, he favored paying down debts. The right-wing onslaught continues, until, mercifully, one white-haired chap asks White if he has been watching what has been happening in the United Kingdom, where the government has adopted austerity policies with predictably dismal results, and how it fits in with his anti-Keynesian view of the world. White says he doesn't know enough about the U.K. to comment. KIA!

Jamie leans over and says we are going to lose: the Hayekians have stuffed the hall. Steve says something similar. After Galbraith and Phelps sum up, Sir H. asks the audience to vote again, and after a few seconds the results appear on the screen behind us. Surprise, surprise: Keynes has won. Fifty-two per cent of the audience says we should listen to him rather than Hayek. Hang on a minute, though. Since the earlier vote, more people have changed their minds in favor of Hayek than Keynes. By the rules of some debates, the other side is the winner. But here is Sir H. declaring Keynes victorious. It's official—or something like that.

Before heading home, I go upstairs for a reception, where drinks are served. A bit later, Jodi Beggs, who covers economics for About.com, tweets:" "The #keyneshayek debate would have been way better had the booze been offered before rather than after." Now, there's a motion all sides can agree upon.

November 8, 2011

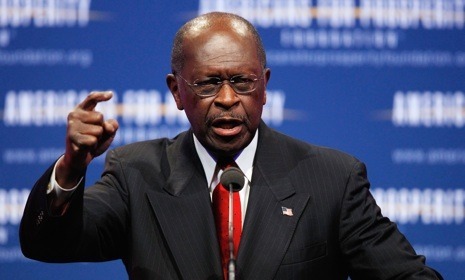

Beyond the Fringe: Herman Cain and the Republicans

In the Hanna-Barbera and Warner Brothers cartoons I grew up on, there was a stock scene where one of the characters rushes off a cliff and, unaware of his predicament, levitates for a few seconds before plunging to his doom. Today, Herman Cain is that character.

"How was your day?" Jimmy Kimmel asked him last night.

"Well, all things considered, I'm still alive," Cain replied. "It got off to somewhat of a rough start. We had a little surprise on TV."

Give Cain points for gall, and, before he impacts the earth in a cloud of dust, ponder this question: What to make of such a fellow and his bizarre if highly popular campaign?

It seems to me that there are two possible answers—one benign, the other less so.

The Fringe Candidate. As my colleague Ryan Lizza noted last week, every Presidential campaign attracts oddballs, idealists, extremists, and rich guys, which isn't necessarily a bad thing. In Ryan's words, "They often enliven debates and force their more electable, centrist colleagues to take uncomfortable stands on difficult issues, which is generally a good thing for our politics." According to this narrative, Cain is just the latest in a long line of fringe candidates that stretches back through Steve Forbes and Lyndon LaRouche to Ross Barnet, Norman Thomas, and General Douglas MacArthur. (In 1948, while the good general was effectively ruling Japan, a group of conservatives entered his name in the Republican primaries.)

The essence of the fringe candidate is, of course, that he (or she) remains on the fringe. Even now it could be argued that Cain satisfies that definition. While political junkies and late-night comedians are consumed by his antics, the population at large isn't necessarily paying much attention. Following the Republican primaries is very much a minority pursuit. Last month, when CNN attracted five million viewers—one in sixty Americans—to its candidates' debate, the network was thrilled. Yesterday morning, when the celebrity site Radar Online broke the news about a press conference featuring Cain's latest accuser, it was the fourth story on its home page, below the news that Lindsay Lohan had left jail and Justin Bieber had described as "a lot of crap" rumors he had fathered a child. (That earth-shaker merited two stories.)

So perhaps this is all much ado about nothing. Cain's bubble has burst, and in a few weeks we will have largely forgotten about him. The campaign pack will have moved on to more significant but less entertaining stories, such as just how far Mitt Romney can go in toadying up to the right. (Judging by his latest voucher plan for Medicare, the answer appears to be: quite a long way.)

The Mainstream Candidate. The problem with the fringe-candidate theory is that it ignores what is happening inside the Republican Party, where, with the rise of the Tea Party, demarcation lines between the fringe and the mainstream have become increasingly blurred. At its grass roots, the Republican Party is no longer a center-right party: it is a nationalist anti-government movement of the right, with resemblances to other right-wing populist movements in history, such as the U.S. People's Party in nineteenth-century America, the Poujadists in post-war France, and the True Finn party in contemporary Finland. It is largely a party of Bible readers, Fox News watchers, and Russ Limbaugh listeners, which, to some extent anyway, has tuned out the mainstream media.

To see where the center of gravity rests in today's Republican Party, you just have to look at the latest poll-of-polls from Real Clear Politics, which shows the avowedly conservative candidates (Cain, Gingrich, Perry, Perry, Paul, Bachman) leading the centrists (Romney and Huntsman) by 61 per cent to 24 per cent. In the Republican primaries, the populist right-wing vote isn't the fringe: it is the main battleground on which the nomination will be decided. Cain, who is still leading Romney by 25 per cent to 23 per cent in the same poll-of-polls, has successfully occupied this terrain. In a recent Gallup poll, of Republican Tea Party supporters and Republican-leaning independents who called themselves Tea Party supporters, he was the clear leader. Perhaps more surprisingly, he was also leading among Republicans in the South, who are overwhelmingly white.

The driving force behind right-wing populism is usually the same: embitterment about the state of the country and anger at the political establishment. Cain, for all his ignorance about issues, knows how to tap into this sentiment and present himself as an alternative. "America has become a nation of crises," he declares in his standard stump speech. "We have an economic crisis. We have an entitlement-spending crisis. We have an energy crisis. We have an illegal-immigration crisis. We have a foggy-foreign-policy crisis. We have a moral crisis. And the biggest crisis of all is we have a severe deficiency-of-leadership crisis." And Cain goes on: "I am a businessman problem-solver, not a politician."

I took these quotes from an interesting article about Cain in next week's Times Magazine, which was posted online yesterday. The writer, T. A. Frank, after following Cain around on the stump and interviewing some of his supporters, offers up the heretical thought that he might even survive the latest sexual harassment allegations, writing, "He will suffer embarrassment. People will cringe at what emerges. And he will continue to poll far better than reason should allow."

Why so? Not because of the "9-9-9" plan or any of his other dubious policy proposals. It is because he speaks to ordinary disillusioned Republicans in language, largely religious language, that they understand and like. "He can articulate a crowd's worst fears—America is falling apart, weakening in the world, suffering economic carnage—and then reassure everyone that, no worries, we can fix it," Frank writes. "If any candidate were able to relate to voters in this way and have a clue what he or she was talking about (there, in Cain's case, is the rub), that person would be unstoppable."

Frank's analysis of Cain's prospects, I disagree with. Even in the cacophonous and largely sealed echo chamber that is Republican politics, repeated allegations of sexual harassment cannot be brushed aside. Much to the relief of Karl Rove and his pals on K Street who are betting the bank on Mitt Romney, Herman is going down. But the God-fearing Americans who have been cheering him on aren't going anywhere. They are the mainstream of the Republican Party.

Photograph by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers