John Cassidy's Blog, page 107

December 22, 2011

Obama's Christmas Present: Republicans Cave

Like most economists, I tend to assume that people act in their own best interests—not in all cases (heavy smokers and chronic gamblers are obvious exceptions) but as a general rule. How then to explain the recent behavior of House Republicans?

In making a U-turn late Thursday afternoon and accepting a deal on extending payroll-tax cuts and unemployment benefits for those who have been out of work for more than six months, Speaker Boehner belatedly acknowledged what had been obvious for days: he and his obstinate colleagues had presented President Obama with was an early Christmas present. It was no surprise that the cave-in came shortly before the evening news; Republicans didn't want to endure another horrible news cycle.

Hours earlier, President Obama had stood in the White House briefing room surrounded by a dozen or so ordinary Americans and read out what it would have meant to such people to lose forty dollars from each paycheck—roughly the cost to the average family of the tax increase that would have kicked in January 1st. There was "Joseph from New Jersey," who said he would have to sacrifice a pizza night with his daughters, and "Pete from Wisconsin," who said he would have to cancel a car trip to visit his father in a nursing home. It wasn't immediately clear whether the purveyors of these sob stories were among the folks standing behind Obama, but that didn't really matter. The White House's enlistment of regular folk, which had started on Tuesday with a call for responses on Twitter and Facebook, had turned into one of the most politically effective stunts of this presidency.

For G.O.P. supporters with any nous at all, it made for painful viewing. Pointing out that the majority of Senate Republicans had already agreed to a proposed compromise, Obama snapped, "Has this place become so dysfunctional that even when people agree we can't get things done? Enough is enough."

With that, at least, Boehner and other Republican leaders could only agree. But how did things come to this pass? Even before Obama's appearance, some senior Republicans spotted a disaster in the making and were calling on their House colleagues to relent. Speaking on the Thursday edition of "The Early Show," on CBS, Senator John McCain said the standoff was hurting the party and its hopes of winning the Presidential election. Karl Rove said more or less the same thing, and so did Newt Gingrich. "Incumbent presidents have enormous advantages," Gingrich said Wednesday. "And I think what Republicans ought to do is what's right for America. They ought to do it calmly and pleasantly and happily."

Also on Wednesday, the Wall Street Journal's editorial page, hardly a haven of moderate views, published a despairing comment, which began:

GOP Senate leader Mitch McConnell famously said a year ago that his main task in the 112th Congress was to make sure that President Obama would not be re-elected. Given how he and House Speaker John Boehner have handled the payroll tax debate, we wonder if they might end up re-electing the President before the 2012 campaign even begins in earnest.

The headline on the Journal editorial was "The GOP's Payroll Tax Fiasco: How did Republicans manage to lose the tax issue to Obama?" But the answer the article provided—political incompetence on the part of McConnell and Boehner—was woefully inadequate. Wary of the dangers they were facing, the two Republican leaders had reportedly agreed to the compromise that passed the Senate extending the tax cuts and unemployment benefits for two months. In return, the White House had provisionally agreed to bring forward its decision on the controversial Keystone XL pipeline.

It wasn't McConnell and Boehner who formed what the Journal editorial aptly referred to as a "circular firing squad." It was the enragés in the House who rebelled against the deal, just as they rebelled this summer against Boehner's efforts to reach a compromise on the debt ceiling and the deficit. The ensuing stalemate helped bring Congress's approval rating down to thirteen per cent in the August Gallup poll. Today, Congress's approval rating is eleven per cent—the lowest figure recorded since Gallup started asking the question in 1974.

Sticking with the self-interest theory for a moment, one possible explanation for the Republicans' actions is that most Congressional districts are now so uncompetitive, due to gerrymandering or whatever, that incumbents have no fear of losing office. I don't find this argument persuasive. Many of the Tea Party supporters swept to victory in a midterm election, which almost always see the party that holds the White House losing seats. Presidential elections are very different. In what is shaping up to be a close race, many members of the Class of 2010 could be voted out.

A more compelling argument is that the Republican Party is no longer a mean electoral machine, but an uneasy alliance of potentially competing groups. As long as they are attacking President Obama, these groups get along fine. But when they have to actually govern and make decisions, big problems arise.

Despite all that has happened, the Republican establishment in Washington is still, fundamentally, the agent of corporate America and its most privileged denizens. Folks like McConnell and Boehner, but also strategists like Rove and Stuart Stevens (Mitt Romney's Svengali figure), believe in holding power, both to keep out the Democrats and to protect the interests of their wealthy supporters. Arrayed beneath this traditional structure is a seething populist movement that contains elements of everything from Know Nothing nativism to Poujadism to Christian fundamentalism to economic libertarianism.

The representatives of this movement didn't come to Washington to boost demand in the economy, to preserve tax breaks for the local gentry, or even, necessarily, to preserve their own seats. They came to put the country on a new path, downsize the federal government, and generally make a racket. After a year in the capital, they have succeeded in only the third aim—hence their frustration.

To Republican congressmen of this ilk, the Senate payroll-tax bill was a typically shoddy Washington compromise; it didn't resolve any outstanding disputes but merely shooed them away for a bit. As it happens, the insurgents were right about that. Extending important tax and spending legislation for a period of two months is no way to run the world's largest economy. But given the political realities of the moment, it was all the leaders of the two parties could cobble together.

In registering their protest vote, Eric Cantor and his crew put themselves in an untenable position, from which the only escape was capitulation. But don't expect President Obama to feel sorry for them. In delaying his departure to Hawaii, the dispute cost him a few days on the beach—but the political benefits he reaped are incalculable.

Photograph: Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

December 20, 2011

Newt Bloody & Battered: Iowa Campaign "in Meltdown"

"Beat on the brat

Beat on the brat

Beat on the brat with a baseball bat

Oh yeah, Oh yeah, uh oh"

—Joey Ramone

Harold Wilson, who served as Britain's prime minister twice during the nineteen-sixties and seventies, famously observed that a week is a long time in politics. Newt Gingrich would surely agree. Going into last Thursday's television debate on Fox, he was the confirmed frontrunner, with a big lead over Mitt Romney in the national polls and in three of the first four primary states: Iowa, South Carolina, and Florida.

Five days later, all is changed, or so it seems. Two new polls show Romney pulling back to level in the national race. In the latest ABC News/Washington Post survey, he and Gingrich are tied at thirty per cent, with Ron Paul at fifteen per cent. A CBS News poll has Gingrich and Romney both with twenty per cent support, and Paul with ten per cent.

In Iowa, where the caucuses will be held two weeks from today (January 3rd), the slump in Newt's fortunes has been even more dramatic. Two polls released yesterday showed him dropping behind Paul and Romney. One of them showed him in fourth place, with Rick Perry ahead of him. Here are the figures from these polls and the previous ones from the same organization.

Public Policy Polling (pdf):

12/11-13 12/16-18

Gingrich 22 14

Romney 16 20

Paul 21 23

Perry 9 10

Insider Advantage (pdf):

12/12 12/18

Gingrich 27 13

Romney 17 18

Paul 12 24

Perry 13 16

As is the case with many state polls, these ones come with a statistical health warning. But the similarity of the findings suggests that Newt's downward lurch is real and, for him, alarming. One of the research organizations that carried out the polls, Insider Advantage, is a Georgia firm with long-established links to Gingrich. The other firm, Public Policy Polling, has found his share of the Iowa vote falling sharply for two weeks in a row—from twenty-seven per cent to fourteen per cent. Meanwhile, his "unfavorability" rating has risen from thirty-one per cent to forty-seven per cent. In the words of a Public Policy Polling news release: "Newt Gingrich's campaign is rapidly imploding."

What can explain this turnaround? It wasn't his performance in the Fox debate, which was characteristically spirited and uncharacteristically disciplined. Under attack from all sides, he kept his temper in check and didn't make any gaffes. The bad news for Newt is that, even on his best behavior, he faces two potentially fatal challenges.

Firstly, as Dean Debnam, the president of PPP, pointed out, Gingrich's support in Iowa was "extremely soft" to begin with. He hasn't spent much time there, he doesn't have a local organization to speak of, and his checkered personal life is an issue for evangelical Christians, who make up a big share of the Republican electorate.

Secondly, and more importantly, the Republican forces opposing Gingrich are clubbing him like a baby seal. After two weeks of uninterrupted battery, it is hardly surprising that his numbers have slumped.

Some of the attacks are coming from the other candidates directly. Paul and Michele Bachmann, in particular, have been flaying Newt mercilessly for his policy flip-flops and self-enrichment schemes. Lately, Rick Perry, who has staked his entire campaign on a two-week bus tour of every settlement of any size in Iowa, has joined in, calling him "the grandaddy of earmarks."

In any primary race, jibes from rival candidates are to be expected. But what has done most damage to Gingrich is a barrage of negative television ads financed by unregulated big money, particularly unregulated big money associated with Romney.

For a couple of weeks now, visitors to Iowa have been reporting that it is difficult to turn on the TV without seeing an ad portraying Gingrich as a corrupt Washington insider. The entity that has paid for the vast majority of these commercials is Restore Our Future, a financial shell organization that was set up and exists solely to funnel money to Romney's campaign. Inside the political trade, such organizations, many of which bear similarly Orwellian names, are called "super PACs." They resulted directly from the Supreme Court's controversial 2010 ruling that allowed corporations, trade unions, and rich individuals to contribute unlimited amounts of money to political campaigns.

At the level of Presidential politics, the impact of the Court's judgment in the case of SpeechNow.org v Federal Election Commission has been mainly theoretical. It has generated a lot of newspaper coverage but not much else. That has now changed. Gingrich is the first Presidential candidate to experience the painful reality of politics in a world of unlimited campaign contributions—as evidenced by Terry Branstad, the Republican governor of Iowa, in today's Times: "The problem is the super PACs come in and spend a million dollars a week blasting a candidate," Branstad said. "And Newt has not been able to put an apparatus like that together.''

Can Gingrich mount a second comeback? Without the resources to compete with Romney and Perry, who is backed by a big Texan super-PAC called Make Us Great Again, it will be tough. Until now, his campaign has been largely absent from the Iowa airwaves. It wasn't until last week that one of his advisers set up a super-PAC dedicated to his election, Winning Our Future, which so far appears to have raised little cash.

Like most of the other candidates, Newt is now in Iowa, where he will spend most of Christmas and New Year's. As a fan and frequent employer of irony, he surely cannot help but appreciate the situation. A candidate who to many embodies the corrupting effect of money on politics faces elimination largely because he hasn't done a good enough job raising slush money.

Photograph by Stephen Morton/AP.

December 13, 2011

The 40 Nicest Things About Newt

Thanks to everybody who responded to the festive challenge I issued on Monday: "What is the nicest thing you can think of to say about Newt Gingrich?" Many of the contributions were funny; some were serious; a few were unprintable. To read all of them, and there were hundreds, you can go to the Comments section on my previous post, to these two pages on Twitter, and to the magazine's Facebook page. In order to save you some time, and brighten up a winter day, I've selected my Top Forty. As they used to do on the radio chart shows, and still do on David Letterman, I'll count them down in reverse order.

40. "Newt is not as stupid as Rush Limbaugh." (Lee Blair via FB)

39. "Newt Gingrich's head is as close to a parallelogram as I've ever seen on a human." @kickinghorse892

38. "He looks like a caricature of himself, this saves cartoonists a lot of effort." @jrt1101

37. "He ties his ties very smartly." @chameleon_poet

36. "He's clearly a hit with the ladies." @franklinmorris

35. "He would make a good pet." @lexinorthwood

34. "He and his wife both have nicely combed hair." @krue0177

33. "When he grins he looks like a goblin." (OOF)

32. "He looks like the Pillsbury Doughboy." @Wulalowe

31. "He looks like Fred Flintstone?" (Scott E. Tyson via FB)

30. "He looks like Sponge Bob Square Pants?" (Linda Chappell McCorkindale via FB.)

29. "He's done his fair share of revitalizing the wedding planning and divorce law businesses." @ZachSmith0307

28. "He makes all other multiply-divorced men look better." (BartPR)

27. "He makes italian rightwing politicians look better." @MrAlboRidolfi

26. "Same as the Devil—he's not lazy." @johanfkirsten1

25. "He has a less than sadistic view of what we should about long-term immigrants." (Nancy Mace Kreml via FB)

24. "He doesn't appear to be a dumb-ass like Perry or a lush, like Boehner." (TALEX101)

23. "Newt Gingrich is definitely less evil than Hitler." @HewstoneW

22. "Pretty sure he hasn't tested positive for any performance enhancing drug." @Greyhound_Dude

21. "He's taller than James Madison." @DRClink

20. "He hasn't shut the government down in years." @english_nerd

19. "If I had a wife and she played the French Horn, I would find an excuse to get out of the house too." @klpaul

18. "He signed a pledge to oppose gay marriage—and we all know his track record for keeping promises related to marriage." (Shane F. Hockins via FB)

17. "Cheerfully provides his current wife with bling." @JayHarveyArts

16. "He's never divorced me." @whinerella

15. "He'll insult someone with a smile." (dgpoyer)

14. "He's not nearly as ignorant as John Cassidy." (peterike)

13. "His name is wonderfully Dickensian." (evo)

12. "Talks space exploration in an inspiring, almost-JFK way. But he'd end Medicare to fund." @JeromePandell

11. "He sent his gay half-sister and her wife a wedding present. Even though he declined to attend the wedding." @susannaeliz

10. "He likes to do it. Now who doesn't like to do it?" @MikeGreggs

9. "He's somebody's grandpa." @playbymarly

8. "He's not MY grandfather." @David_Eads

7. "His mother seemed to like him, in that interview with Connie Chung. Remember?" (Mogambo)

6. "He's turned 'historian' into one of America's highest paying professions." (cocofood)

5. "For a fat man, he doesn't sweat that much." @ElaineLiner

4. "There's not two of him." @mhobson12

3. "I may be wrong, but I don't think he's tweeted his penis." (newyorker8)

2. "Put a beard on him and he'd make a great Santa. Assuming he'd let the kids have the gifts without working for 'em." (BlueSwirl)

1. "He's the one to get Obama reelected." (grgpap74)

December 12, 2011

A Festive Challenge: "What Is the Nicest Thing You Can Think of to Say About Newt Gingrich?"

I know you guys still think I was bunking off over the weekend, partying and watching the Golf Channel when I should have been following the debate, boning up on why evangelicals are so attached to Israel (apparently, it's all to do with the Book of Revelation), and finding out where Jon Huntsman's cute daughters went (New Hampshire, perhaps).

Actually, I spent a good deal of time and effort on what I hope will turn into an important social survey—a kind of Kinsey report for the culture war. Like many seminal pieces of research, mine is based on a deceptively simple methodology. It consists of walking up to people at parties and other social events and asking them this question:

"What is the nicest thing you can think of to say about Newt Gingrich?"

I then stand back from the subject, lest his or her spluttering infects me with whooping cough or Asian flu. Once he/she has recovered, I write down the answer.

My research began on Saturday night, and the first subject was my wife, who has been known to howl in pain when Newt's big square head appears on the screen. The first time I put my question to her, she thought I was joking. Then she thought about it, scrunched her face up, and replied, "He believes his own shit. He doesn't seem to be pandering."

That was surprisingly positive. I noted it down in the spiral notebook I had slipped into my jacket. Shortly after we arrived at our first engagement, a dinner party in Brooklyn Heights, I buttonholed our host, a massively well-read English professor. "I heard a story that he likes spending the night in a zoo with his grandchildren," he said of Gingrich. "I don't know if that's true, but if it is that's the nicest thing I can think to say about him."

Who said members of the liberal élite are closed-minded? I moved on to another guest, one of my wife's best friends, who is a publicist at a major magazine. "There's really nothing," she said dismissively. "If he was a philanderer and good-looking that would be O.K.—like Bill Clinton. But he's a philanderer and he's hideous looking."

Oh, well. Can't win 'em all. I approached our hostess, a newspaper columnist, who had been busy working on the main course.

"What's the great quote?" she said. "He divorced his first older wife because she wasn't pretty enough to be First Lady, and she had cancer anyway. At least he gave an older woman a chance."

True enough. Across the room, I sat down next to a film curator, who told me of his desire to be locked in a room for a year, so he could get to all the projects he had been putting off. When I popped the Gingrich question, he fell silent for a moment. "Well," he said. "He's educated. He's articulate and knowledgeable—he's somewhat intelligent. But it doesn't matter how intelligent you are if you are a bigot. I mean, he's an appalling person. This stuff about child labor. He's a scary prospect. What I say to reassure myself is he's so unlikeable that he would never be elected. But that's what they said about Nixon."

A preschool teacher on the other end of the couch had been listening to our conversation. I turned to her, but before I could blurt out my question she got up and walked away.

"Nothing," she said, looking back. "I have nothing nice to say about him."

That was mildly discouraging. Fortunately, her husband, a writer and history buff, was more amenable to my inquiries. "I like that Newt's favorite President is George Washington," he said. "I like the way he presents himself and says, I'm going to dazzle you with history. I like the way that in one of his recent books he writes about the slaves who fought on the Union Side in the Battle of the Crater but doesn't mention how after the battle they got murdered indiscriminately."

The dinner went on rather longer than expected. By the time we reached our second engagement, a Christmas party at the house of a book publisher, it was close to midnight, and the remaining guests were too sloshed to take my research seriously.

"Fuck Gingrich," said a writer and rock musician I've known since back in the day. I took his advice and put away my notebook. On Sunday morning, I followed up by e-mail, and this time I got a proper response:

The guy is so horrifying that the nicest thing I can say is that his Contract with America and attacks on the poor inspired me to write a song about him. The only political song I have ever written in my life. I would have to dig up the lyrics. But it was called "Man of the House," as in "What kind of man of the house would take food from a baby's mouth?" At the risk of sounding like a jerk and quoting myself, I remember the opening line was: "Here's what I know / a stingy man always pays twice." The other nice thing I can say about him is he looks like a clown without makeup. Which is say his photograph inspires the kind of laughter I can do without.

I also received this response from my book publisher friend: "He's historically minded."

And this one from a writer of fiction and other stuff: "Nicest? No qualifiers? Erm, intellectually ambitious, irrepressible, an independent spirit, unimpeded by guilt issues."

That answer sounded almost enthusiastic. Unfortunately, I had to rule it out of my sample on the grounds that its author is a) English, b) willfully contrarian, and c) suffering the mental ravages of giving up drinking to finish a new play.

Later in the morning, we went out to New Jersey to visit my in-laws, two classical-music buffs who are avid readers of the Times, The Nation, and the New York Review of Books. "Let me think," my mother-in-law said, when I ruined her day by bringing up Newt's name. She didn't have to cogitate for long.

"I can't think of anything even half-nice to say about him," she said. "He's an appalling man—truly despicable. When you think of the people who used to run for President, like Adlai Stevenson and Dwight Eisenhower, it's just shocking."

My father-in-law, a thoughtful and gentle fellow, didn't say anything. I thought perhaps he hadn't heard the question. But about forty-five minutes later, he turned to me and said, "I still can't think of anything."

That was pretty much it for the first round of interviewing. To take the research project further, I've decided to move it online. If you'd like to participate, go to the comments section below. (If you haven't registered with the site, you will need to do that first.) Alternatively, you can tweet your message. Address it to @TNYJohnCassidy and include this hash tag: #nicenewt

Depending on the responses, I'll highlight some of them in a subsequent post, and maybe try and rope in some of my esteemed colleagues, such as Hendrik Hertzberg, whose pointed and erudite Comment about Newt in this week's magazine I scoured in vain for anything that could be categorized as "nice."

So shoot away. Don't try to be too clever. Just say what you think. And don't forget to answer the question: "What is the nicest thing you can think of to say about Newt Gingrich?"

Photograph: Scott Eells/Bloomberg via Getty Images.

December 11, 2011

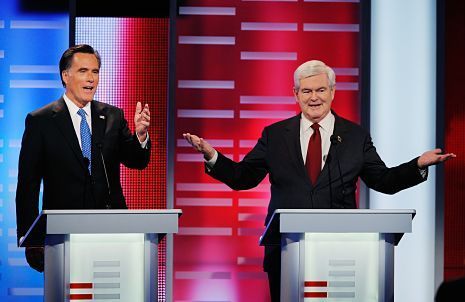

Debate Cheat Sheet: Newt Up, Mitt Down, Ron Rising

O.K, admit it: On Saturday night, while Newt Gingrich was busy relating how he has asked God for forgiveness for his adulterous fornications and Mitt Romney was challenging Rick Perry to a ten-thousand-dollar wager, you were out doing the festive rounds. Don't feel bad. Only a shut-in, a depressive, or a recovering political junkie who has forgotten to take his methadone would willingly spend one of the big social nights of the year watching a two-hour Republican presidential debate. Truly: What sort of a downer would that be?

I didn't watch it either—I had an engagement dinner and a Christmas party to attend—but being a dutiful correspondent, I taped it, read the online coverage, and watched the Sunday-morning political shows to get the opinions of various "professionals" who, a month ago, were treating Romney as a shoo-in and Gingrich as a museum piece. So as a service to the hungover, the apathetic, and the sensible people with better things to do, here is a quick wrap:

The conventional wisdom: Newt won. Romney needed to stop Gingrich's momentum—and he didn't. Ergo Newt comes out best, and, in fact, it's worse than that for Mitt. By casually offering to bet Perry more than a fifth of the annual median household disposable income over whether he ever supported an individual mandate for healthcare insurance, he came across as an out-of-touch rich doofus.

Sunday-morning money quotes:

"At this stage, it would be an upset if Romney won"—Chuck Todd, political editor, NBC News

"This is Newt Gingrich's wheelhouse. Robo-combat—nobody enjoys it like him"—Lisa Myers, NBC News

As I saw it: Newt was even more puffed up and annoying than usual. In saying of the Palestinians, "These people are terrorists,"a statement blatantly aimed at the six out of ten Iowa Republicans who describe themselves as born-again or evangelical Christians, he answered Hunter Thompson's famous question about President Nixon's 1972 campaign: How low do you have to go to be President of this country? Newt, we now know—did we ever doubt it?—will dig all the way to China.

Romney, on the other hand, still appears to think he is standing for the rules committee of his country club, or perhaps for chairmanship of the local branch of the A.A.R.P. "Sobriety, care, stability," he said, listing his virtues. "I am not a bomb-thrower, rhetorically or politically." Earth to Mitt: this is the Republican Party in 2012. If you can't figure out how to channel the anger and resentment that drives the grass roots of the party, you won't make it out of January.

Most of the other candidates had their moments, particularly Ron Paul, who poked Gingrich in his most tender spot: the hidden pouch where he stashed the $1.6 million he received from Freddie Mac. As far as the horse race is concerned, Paul is now the big unknown.

With another solid debate performance behind him, he is well placed to pull an upset in Iowa, where he is running second to Gingrich. "He's got the most bumper stickers; he's got the most yard signs; he's got the most enthusiasm," Iowa governor Terry Branstad said on "Meet the Press." Perhaps the biggest strike against Paul is that the pundits are now taking him seriously. He even earned a Sunday-morning money quote of his own:

"Ron Paul can win in Iowa"—Jon Karl, ABC News

Uh, oh Mitt Romney, for one, will be hoping that didn't sound the death knell for the Paul surge. Right now, a Paul victory is about the only thing that could slow Gingrich's momentum.

December 9, 2011

Why the Euro Isn't Finished

If there's one thing practically everybody seems to be able to agree upon, it is that the euro is destined to collapse, and with it the great post-war vision of European integration. Whether you listen to newspaper columnists, financial bloggers, Wall Street analysts, or hedge-fund managers, the message you hear is the same. All these efforts to save the euro are ultimately doomed. They might as well give up now, let it crash around them, and start over.

Take the reaction to Friday's news that seventeen of the twenty-seven countries in the European Union have agreed to forge closer economic ties, with more centralized control over the tax and spending policies of individual governments, and nine of the ten other countries have agreed to consider such a move. (Britain was the sole country to reject the idea out of hand.) The reaction fell along familiar lines: too little, too late; a Band-Aid where surgery is needed; yet another effort to kick the can down the road. (Mastery of stale metaphors appears to be a necessary qualification for Wall Street analysts.)

Up to a point, the skeptics have a point. Friday's deal doesn't tackle the issue at the heart of the continent's problems, which is the same issue in all debt crises: bad debt. But the decision to move closer to a fiscal union is another important step in creating an institutional framework for resolving the fundamental issues. While the crisis isn't going to end next week, or next month, the outlines of a long-term solution are coming into view. Whether there is time for this solution to play out hinges crucially on the European Central Bank, which is the other key player in this game of governments versus markets.

When it comes down to it, the euro zone has two problems, which have been clear all along: a solvency problem and a liquidity problem. The governments of several peripheral countries—Greece, Portugal, Ireland—have issued debts they can't hope to pay back. (Insolvency.) And the governments of several core countries—Italy, Spain, and even France—have debts big enough that in a crisis they could find difficulty rolling over their existing bonds and issuing new ones. (Illiquidity.)

In the past couple of months, the moment of crisis has arrived. With investors shunning most European bonds, countries like Italy and Spain have seen their funding costs soar to unsustainable levels. As always happens in big financial crises, a self-reinforcing spiral has come into effect, which threatens the entire system: buyers get scared, which causes prices to fall, which scares off more buyers, which causes further falls in prices until the market virtually freezes up.

To bring the debt crisis to an end, the European governments will ultimately have to deal with the solvency problem, which will involve further restructurings and write-offs. Until recently, there was no mechanism to do this. Every time Greece or Ireland wanted a bailout, they had to deal with all the other E.U. members, who can seldom agree on anything. In the past few months, though, the Europeans have set up two bailout funds: an interim European Stability Mechanism and a permanent European Financial Stability Facility, which will start operating in July, 2012. Through these institutions, the E.U., together with the International Monetary Fund, will have the capacity to further restructure the debts of the heavily indebted peripheral countries.

But that is going to take time, and it hinges on stabilizing the situation in solvent but illiquid countries, such as Italy and Spain, and preventing the contagion from spreading to other countries, such as France. This is where the European Central Bank comes in. For only it has the ability, through its capacity to create money and spend it on financial assets of its choice, to reverse the self-fulfilling "run" on the debt markets of Italy in particular. If the E.C.B. said tomorrow that it was committed to acting as the buyer of last resort in the bond markets of euro-zone governments that are fundamentally solvent but which face short-term funding issues, the crisis would recede.

Until now, the E.C.B. has resolutely avoided saying any such thing, giving the upper hand to hedge funds and other institutions that are busy shorting euro-zone debt. This is partly because the European Union treaty that set up the central bank doesn't anywhere mention it acting as a lender of last resort to member governments. (The E.C.B. does act like a lender of last resort to European banks. Earlier this week, it expanded these lending facilities.) But the main thing that has held back the E.C.B. is a desire to force member countries to deal with their own problems, particularly irresponsible ones like Greece and Italy.

For the past couple of months, a game of chicken has been playing out in which the markets and the troubled governments have been pleading with the E.C.B. to step in, and the E.C.B. (and Germany, which holds an effective veto on its actions) has been saying that it first wants to see real commitments to reform.

What hasn't been fully appreciated, particularly on this side of the Atlantic, is how significant those commitments have been. In Greece and Italy, we have witnessed ineffective but democratically elected governments replaced with national-unity governments headed by technocrats committed to fiscal austerity. In Spain, too, a new government has come to power and promised not to let up in the drive to cut spending and deficits.

The other thing that the E.C.B. and Germany wanted was a Europe-wide commitment to fiscal discipline, and that is what Friday's agreement in Brussels delivered. In future, countries that run large budget deficits will face automatic sanctions unless they can persuade a majority of other member states to exempt them, which won't be easy. Hence Angela Merkel's verdict: "The breakthrough to a stability union has been achieved."

We shall see about that. Much now depends on the E.C.B., which is emitting mixed signals. On Thursday, Mario Draghi, its Italian head, seemed to downplay the suggestion that it would now step up its bond purchases. But on Friday he hailed the new agreement as "a very good outcome for euro area members" which would "be the basis for a good fiscal compact and more disciplined economic policy in euro area countries."

After all that has happened, I cannot believe that the E.C.B. will simply stand pat and allow the bond traders to bring down the euro. Some critics portray it as a remote, out-of-touch institution that cares about but one thing: price stability. That is going too far. Draghi, an Italian who holds an economics Ph.D. from M.I.T. and spent three years working at Goldman Sachs, is a moderate technocrat rather than an ideologue. Just as important, the two new German representatives on the board of the E.C.B. are both close to Merkel, and can be expected to do her bidding.

I don't expect any dramatic announcements next week from the E.C.B. That would look too much like it was buckling to the politicians. But over the coming weeks and months, I expect it to step up its bond purchases, both through its Securities Markets Program and, eventually, through a policy of quantitative easing that mimics what the Fed has done here. If this happens, other buyers should return to the continent's stricken bond markets, and yields should go down, easing the immediate crisis.

Such a turnaround wouldn't solve all of Europe's problems, but it would buy the E.U. some more time to tackle them. In concert with further restructuring of the debts of places like Greece and Ireland, the continent's big banks are going to have to be properly recapitalized, possibly via a European version of the TARP. And in order to head off a lengthy and grinding recession, the governments of the less affected countries, notably Germany and France, are going to have to boost demand by introducing a fiscal stimulus. (Quantitative easing, by lowering the value of the euro from its current overvalued level, would help with this, too.)

None of this is going to be easy. It is going to be a long, hard grind, and along the way there is always the possibility that confidence in the markets will evaporate completely, prompting a crisis that would prove the skeptics right. If the E.C.B. fails to play its allotted role, such an outcome is highly likely. We shouldn't underestimate the possibility of disaster. But nor should we underestimate the commitment of the European countries, and especially Germany and France, to muddle through and hold the euro zone together. They've done it so far, and made more progress than many give them credit for.

Euro Zone: Slow and Dysfunctional—But Not Finished

If there's one thing practically everybody seems to be able to agree upon, it is that the euro is destined to collapse, and with it the great post-war vision of European integration. Whether you listen to newspaper columnists, financial bloggers, Wall Street analysts, or hedge-fund managers, the message you hear is the same. All these efforts to save the euro are ultimately doomed. They might as well give up now, let it crash around them, and start over.

Take the reaction to Friday's news that seventeen of the twenty-seven countries in the European Union have agreed to forge closer economic ties, with more centralized control over the tax and spending policies of individual governments, and nine of the ten other countries have agreed to consider such a move. (Britain was the sole country to reject the idea out of hand.) The reaction fell along familiar lines: too little, too late; a Band-Aid where surgery is needed; yet another effort to kick the can down the road. (Mastery of stale metaphors appears to be a necessary qualification for Wall Street analysts.)

Up to a point, the skeptics have a point. Friday's deal doesn't tackle the issue at the heart of the continent's problems, which is the same issue in all debt crises: bad debt. But the decision to move closer to a fiscal union is another important step in creating an institutional framework for resolving the fundamental issues. While the crisis isn't going to end next week, or next month, the outlines of a long-term solution are coming into view. Whether there is time for this solution to play out hinges crucially on the European Central Bank, which is the other key player in this game of governments versus markets.

When it comes down to it, the euro zone has two problems, which have been clear all along: a solvency problem and a liquidity problem. The governments of several peripheral countries—Greece, Portugal, Ireland—have issued debts they can't hope to pay back. (Insolvency.) And the governments of several core countries—Italy, Spain, and even France—have debts big enough that in a crisis they could find difficulty rolling over their existing bonds and issuing new ones. (Illiquidity.)

In the past couple of months, the moment of crisis has arrived. With investors shunning most European bonds, countries like Italy and Spain have seen their funding costs soar to unsustainable levels. As always happens in big financial crises, a self-reinforcing spiral has come into effect, which threatens the entire system: buyers get scared, which causes prices to fall, which scares off more buyers, which causes further falls in prices until the market virtually freezes up.

To bring the debt crisis to an end, the European governments will ultimately have to deal with the solvency problem, which will involve further restructurings and write-offs. Until recently, there was no mechanism to do this. Every time Greece or Ireland wanted a bailout, they had to deal with all the other E.U. members, who can seldom agree on anything. In the past few months, though, the Europeans have set up two bailout funds: an interim European Stability Mechanism and a permanent European Financial Stability Facility, which will start operating in July, 2012. Through these institutions, the E.U., together with the International Monetary Fund, will have the capacity to further restructure the debts of the heavily indebted peripheral countries.

But that is going to take time, and it hinges on stabilizing the situation in solvent but illiquid countries, such as Italy and Spain, and preventing the contagion from spreading to other countries, such as France. This is where the European Central Bank comes in. For only it has the ability, through its capacity to create money and spend it on financial assets of its choice, to reverse the self-fulfilling "run" on the debt markets of Italy in particular. If the E.C.B. said tomorrow that it was committed to acting as the buyer of last resort in the bond markets of euro-zone governments that are fundamentally solvent but which face short-term funding issues, the crisis would recede.

Until now, the E.C.B. has resolutely avoided saying any such thing, giving the upper hand to hedge funds and other institutions that are busy shorting euro-zone debt. This is partly because the European Union treaty that set up the central bank doesn't anywhere mention it acting as a lender of last resort to member governments. (The E.C.B. does act like a lender of last resort to European banks. Earlier this week, it expanded these lending facilities.) But the main thing that has held back the E.C.B. is a desire to force member countries to deal with their own problems, particularly irresponsible ones like Greece and Italy.

For the past couple of months, a game of chicken has been playing out in which the markets and the troubled governments have been pleading with the E.C.B. to step in, and the E.C.B. (and Germany, which holds an effective veto on its actions) has been saying that it first wants to see real commitments to reform.

What hasn't been fully appreciated, particularly on this side of the Atlantic, is how significant those commitments have been. In Greece and Italy, we have witnessed ineffective but democratically elected governments replaced with national-unity governments headed by technocrats committed to fiscal austerity. In Spain, too, a new government has come to power and promised not to let up in the drive to cut spending and deficits.

The other thing that the E.C.B. and Germany wanted was a Europe-wide commitment to fiscal discipline, and that is what Friday's agreement in Brussels delivered. In future, countries that run large budget deficits will face automatic sanctions unless they can persuade a majority of other member states to exempt them, which won't be easy. Hence Angela Merkel's verdict: "The breakthrough to a stability union has been achieved."

We shall see about that. Much now depends on the E.C.B., which is emitting mixed signals. On Thursday, Mario Draghi, its Italian head, seemed to downplay the suggestion that it would now step up its bond purchases. But on Friday he hailed the new agreement as "a very good outcome for euro area members" which would "be the basis for a good fiscal compact and more disciplined economic policy in euro area countries."

After all that has happened, I cannot believe that the E.C.B. will simply stand pat and allow the bond traders to bring down the euro. Some critics portray it as a remote, out-of-touch institution that cares about but one thing: price stability. That is going too far. Draghi, an Italian who holds an economics Ph.D. from M.I.T. and spent three years working at Goldman Sachs, is a moderate technocrat rather than an ideologue. Just as important, the two new German representatives on the board of the E.C.B. are both close to Merkel, and can be expected to do her bidding.

I don't expect any dramatic announcements next week from the E.C.B. That would look too much like it was buckling to the politicians. But over the coming weeks and months, I expect it to step up its bond purchases, both through its Securities Markets Program and, eventually, through a policy of quantitative easing that mimics what the Fed has done here. If this happens, other buyers should return to the continent's stricken bond markets, and yields should go down, easing the immediate crisis.

Such a turnaround wouldn't solve all of Europe's problems, but it would buy the E.U. some more time to tackle them. In concert with further restructuring of the debts of places like Greece and Ireland, the continent's big banks are going to have to be properly recapitalized, possibly via a European version of the TARP. And in order to head off a lengthy and grinding recession, the governments of the less affected countries, notably Germany and France, are going to have to boost demand by introducing a fiscal stimulus. (Quantitative easing, by lowering the value of the euro from its current overvalued level, would help with this, too.)

None of this is going to be easy. It is going to be a long, hard grind, and along the way there is always the possibility that confidence in the markets will evaporate completely, prompting a crisis that would prove the skeptics right. If the E.C.B. fails to play its allotted role, such an outcome is highly likely. We shouldn't underestimate the possibility of disaster. But nor should we underestimate the commitment of the European countries, and especially Germany and France, to muddle through and hold the euro zone together. They've done it so far, and made more progress than many give them credit for.

December 8, 2011

A "New Newt"?

Now that Newt Gingrich is the designated frontrunner in the Republican primaries, politicians and pundits alike are rushing to find a rationalization for the turnaround in his fortunes, even though the explanation is starting them in the face: setting aside Ron Paul, who remains a live contender, the other conservative candidates turned out to be an inflexible extremist (Michele Bachmann), a village dolt (Rick Perry), and a snake-oil salesman (Cain).

The explanation du jour harks back to the early stages of Richard Nixon's 1968 campaign, when observers spotted something different about a man previously dismissed as an incorrigible downer and elector-repellant. In December, 1967, after Nixon visited Eugene, Oregon, a local newspaper reported that he seemed "more relaxed, more given to easy humor, less testy than the drawn, tired figure who debated Jack Kennedy or the angry politician who conceded his California defeat with such ill grace." By the end of December, Time magazine had anointed him as "the man to beat." (The Wikipedia entry on Nixon's '68 campaign has excellent links to these and other articles from the time.)

In Gingrich's case, the reassessment coincided with his surge in the polls in Iowa, Florida, and other early-voting states. It began with some of his former colleagues in the House of Representatives. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, who helped organize the 1997 coup that ended Gingrich's controversial term as Speaker, told reporters on Capitol Hill, "It wasn't easy to do what he did—he was the first Republican leader in the Congress in 40 years, and I think it showed. I think he has learned from those experiences." Noting that he had spoken with Gingrich since his recent surge and affirming that he "doesn't hold grudges because the coup was held in my office," Graham added, "I'm talking to a different guy."

Journalists, too, have been spotting some previously ignored plusses in Gingrich's record. Writing at Politico, Joe Scarborough, the MSNBC host who was once a conservative Republican congressman, gave him credit for leading a movement that balanced the federal budget and passed welfare reform, adding, "Is there a Republican in the field who can top these achievements?" Even at newyorker.com, one commentator described Newt as "a gifted speaker, a quick wit, and a battle-hardened political brawler." (Yes, that historical revisionist would be me—in my report on his trip to New York earlier this week.)

So is there really a "New Newt"? Or, as with the "New Nixon," is it a case of deliberate hype and wishful thinking? Despite acknowledging his verbal and pugilistic talents, which had been underestimated (or forgotten), I am somewhat skeptical. As a general rule, I am a subscriber to the theory that leopards can't change their spots—not at the age of sixty-eight, anyway.

Until presented with a lot more evidence to the contrary, I will assume this is the same Newt who emerged from obscurity to head a radical insurgency that wrested control of the Congress from the Democrats and from the Republican establishment; who inflicted such damage on President Clinton that he was driven to recall Dick Morris, and who then, at the peak of his power and influence, self-destructed in spectacular fashion. This is the same Newt who left his first two wives, asking their successors to marry him before informing them. And this is the same Newt who, after he left Congress, sold his résumé, his access, and his political knowledge to large companies that did business with the federal government, using some of the proceeds to run up a five-hundred-thousand-dollar bill at Tiffany's.

As the human-resource folks would have it, you are your résumé. If you don't want to take my word for it, and I wouldn't necessarily blame you, read the lengthy Profile of Gingrich that my colleague Connie Bruck wrote in 1995. Then go to a much more recent piece, by John H. Richardson, which appeared in the September, 2010, issue of Esquire. If this article had come out last month it would be everywhere. Because it was published last year, and most reporters are obsessed with news, I've hardly seen it referred to. But for anybody who wants to understand Newt, and how the "New Newt" relates to the "Old Newt," it is essential reading.

Here, via Richardson, is Newt on Newt:

There's a large part of me that's four years old. I wake up in the morning and I know that somewhere there's a cookie. I don't know where it is but I know it's mine and I have to go find it. That's how I live my life. My life is amazingly filled with fun.

And here's Newt on Newt and Callista, his third wife (the recipient of his purchases at Tiffany's):

Callista and I kid that I'm four and she's five and therefore she gets to be in charge, because the difference between four and five is a lot.

The spine of Richardson's piece, and what makes it truly memorable, is a long interview he conducted with Newt's second wife, Marianne Gingrich, who was married to him from 1991 until 1999, and who served as his closest adviser and confidante throughout his first rise and fall. "We started talking and we never quit until he asked me for a divorce," Marianne recalled to Richardson, who reports that she harbors little bitterness and often speaks with great kindness about her former husband. "She still believes in his politics," Richardson writes. "She supports the Tea Parties. She still uses the name Marianne Gingrich instead of going back to Ginther, her maiden name."

Here, then, is some more of what Marianne Gingrich has to say about Newt Gingrich:

On Newt:

He was impressed easily by position, status, money. He grew up poor and always wanted to be somebody, to make a difference, to prove himself, you know. He has to be historic to justify his life….Newt trained himself. He wasn't a natural. He doesn't have natural instincts and thoughts. Everything has to be a thought process first. It took years and years. It wasn't, "I have this insight, I am compelled, I can do no other." It was step by step by step, and it was all mental, all learned behavior.

On Newt at his peak in the nineteen-nineties:

Newt always wanted to be somebody. That was his vulnerability, do you understand? Being treated important. Which means he was gonna associate with people who would stroke him, and were important themselves. And it that vulnerability, once you go down that path and it goes unchecked, you add to it. Like: "Oh, I'm drinking, who cares?" Then you start being a little whore, 'cause that's what comes with drinking. That's what corruption is—when you're too exhausted, you're gonna go with your weakness. So when we see corruption, we shouldn't say, "They're all corrupt." Rather, we should say, "At what point did you decide that? And why? Why were you vulnerable?"All he wanted was to be accepted into the country club. And then he arrives at the country club, and he's just not welcome. "Yeah, but I belong here," he said. "I earned my we way to this. I earned it."

On Newt's business interests and a possible Presidential campaign (when the interview was conducted, he hadn't yet declared his candidacy):

There's no way.He could have been President. But when you try and change your history too much, and try and recolor it because you don't like the way it was or you want it to be different to prove something new you lose touch with who you really are. You lose your way….

He believes that what he says in public and how he lives don't have to be connected. If you believe that, then, yeah, you can run for president….

He always told me that he's always going to pull the rabbit out of the hat.

On whether Newt would run:

Possibly. Because he doesn't connect things like normal people. There's a vacancy—kind of scary, isn't it?

On their courtship:

He asked me to marry him way too early. And he wasn't divorced yet. I should have known there was a problem.Within weeks.

It's not so much a compliment to me. It tells you a little bit about him.

On their divorce and Newt's subsequent remarriage and conversion to Roman Catholicism:

He'd already asked her to marry him before he asked me for a divorce. Before he even asked….It's hysterical. I got a notice that they wanted to nullify my marriage. They're making jokes about it on local radio. The minute he got married, divorced, married divorced—what does the Catholic Church say about this?

When you try an change your history too much, you lose touch with who you really are. You lose your way.

That's Newt. Who knows what will become of him this time around? Maybe, he will sweep Iowa, Florida, and South Carolina, emerging as an unstoppable force. But he'll be doing it not as "New Newt," the clinically reconstructed and repackaged product of a John Mitchell/Roger Ailes-style body shop—but as Newt Gingrich, warts and all, the man we all know and love/hate/enter your own word here. (No expletives allowed.)

Photograph by Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images.

December 7, 2011

Obama Speech Reax: Turning Point or Hot Air?

If President Obama's intention in channelling Teddy Roosevelt yesterday was to rally the center-left troops, he largely succeeded.

The Times editorial page said the speech

felt an awfully long time in coming, but it was the most potent blow the president has struck against the economic theory at the core of every Republican presidential candidacy and dear to the party's leaders in Congress. The notion that the market will take care of all problems if taxes are kept low and regulations are minimized

On the Huffpo, Bob Reich, the former labor secretary, who has been vocal in his criticisms of Obama, hailed "the most important speech of his presidency," adding,

Here, finally, is the Barack Obama many of us thought we had elected in 2008. Since then we've had a president who has only reluctantly stood up to the moneyed interests Teddy Roosevelt and his cousin Franklin stood up to.

Judging by the response to my post yesterday, in the comments section and on Twitter, many Obama supporters agreed that it represented a big improvement. One friend of mine e-mailed last night to say she had gone to Obama's campaign Web site and made a donation, adding, "We need to reinforce this trend."

Of course, words are just words—"This speech, like 99% of presidential speeches, will be shortly forgotten and historically irrelevant," tweeted Matt Yglesias, who recently moved his informative blog to Slate. Yglesias also tweeted a link to Obama's jobs speech to Congress from a few months back, adding, "Obama did this pivot in September; it changed nothing and now everyone's forgotten."

Count me as a skeptic. On this occasion, though, I think Yglesias and other critics went too far. For sure, most Presidential speeches don't mean much. But some do, and this was one of them—for various reasons.

First: it had some real heft. When was the last time you heard a President citing studies showing declining social mobility between the poor and the middle class? Or talking about the growing gap between productivity and wages? As Reich pointed out, "It's the first time (Obama) or any other president has clearly stated the long-term structural problem that's been widening the gap between the very top and everyone else for thirty years."

At last, the President did what I and others have been calling on him to do for yonks. He presented a coherent narrative of what has been happening to America, and it was a very disturbing narrative:

For most Americans, the basic bargain that made this country great has eroded. Long before the recession hit, hard work stopped paying off for too many people. Fewer and fewer of the folks who contributed to the success of our economy actually benefitted from that success. Those at the top grew wealthier from their incomes and investments than ever before.A financial sector where irresponsibility and lack of basic oversight nearly destroyed our economy.

The typical CEO who used to earn about 30 times more than his or her workers now earns 110 times more. And yet over the last decade, the incomes of most Americans have actually fallen by about six percent.

Inequality also distorts our democracy. It gives an outsized voice to the few who can afford high-priced lobbyists and unlimited campaign contributions, and runs the risk of selling our democracy to the highest bidder.

If you go and read Obama's speech to Congress on September 8th, you will find little of this. He was then calling on Congress to pass his jobs bill, which combined tax cuts with targeted infrastructure investments. The pivot was away from debt ceilings and deficit reduction toward more stimulus spending, although, of course, Obama didn't use that word.

Another reason the Kansas speech was important is that it signaled that Obama intends to fight next year's election on a traditional Democratic platform: defending the middle class. Back in 2008, John Edwards and (to a lesser extent) Hillary Clinton were the class warriors. Obama, although he did end up proposing a middle-class tax cut of his own to blunt Clinton's appeal, ran on a platform in which economics was subservient to his broader vision of hope and change. This time around, Obama seems to be taking as his model Bill Clinton, one of whose slogans in 1992 was 'The Forgotten Middle Class"; or perhaps even Teddy Roosevelt's ill-fated "Bull-Moose" campaign of 1912, where he ran on a Progressive Party platform that declared, "To destroy this invisible Government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day."

Is Obama really morphing into the destroyer of Standard Oil and other oppressive monopolies, a President who described the financial and industrial titans of his day as "malefactors of great wealth"? Of course he isn't. Like many successful politicians who come from nowhere, he is too pleased to be part of the establishment to believe truly that it needs overturning. When push came to shove during the financial crisis, he went with Tim Geithner and Larry Summers, who were ultimately (and for some defensible reasons) more interested in preserving the financial system than reforming it.

As Yglesias rightly pointed out, Tuesday's speech didn't break much new ground policy-wise, and the economic measures that Obama is promoting—extending the payroll tax cut; allowing the Bush tax cuts for high earners to expire; spending a bit more on infrastructure and research—are hardly up to the task of reversing thirty years of pro-inequality policies.

That all said, I still think historians will look back on Tuesday's address and accord it significance. In bringing to the fore inequality, tax policy, and Wall Street malfeasance—all the issues that Occupy Wall Street has been banging on about for months—Obama has acknowledged that the political climate is changing, and that he has been behind the curve. If he goes ahead and tackles the Republicans on these issues with some of the fire that Teddy Roosevelt and his fifth cousin Franklin exhibited, the speech will come to be seen as the moment he laid down his marker for a second term. If, on the other hand, it was just a speech designed to rally the faithful, if Obama now goes back into his defensive, centrist crouch—then the trip to Kansas will go down as a historic missed opportunity.

Photograph by Julie Denesha/Getty Images.

December 6, 2011

Invoking Teddy Roosevelt, Obama Finds His Voice

First an admission: just before President Obama followed in the footsteps of Theodore Roosevelt and went to Osawatomie, Kansas to deliver a populist speech about inequality and the middle class, I had prepared a post criticizing the White House for having the temerity to compare him, at least implicitly, to one of America's truly great Presidents.

Here part of what I had written:

From a tactical perspective, summoning the ghost of Roosevelt is a clever move. It reinforces the White House line that the Republican Party has strayed from its center-right roots and morphed into an extremist organization populated by firebrands like Ron "abolish the Fed" Paul, Michele "send illegal immigrants home" Bachmann, and Newt "put poor kids to work" Gingrich. On a broader level, though, I am not sure that invoking Teddy Roosevelt is such a wise idea for the White House. When it comes to actual achievements, as opposed to rhetoric, Obama's record cannot seriously be compared with Roosevelt's.

During his seven years in office (1901-1908), Roosevelt pushed through a series of reforms that largely define what historians now call "the Progressive Era."

As a matter of history, I stand by that. But once I read Obama's speech, I realized I had missed the point, and the news. This isn't the President saying he deserves to be on Mount Rushmore. This is Obama seeking to define the themes he intends to run on next year, to energize his disillusioned base, and to capitalize on a big change in the political climate. Teddy Roosevelt, whose famous "New Nationalism" speech in 1910 called upon the three branches of the federal government to put the public welfare before the interests of money and property, merely provided a convenient framing device.

Whatever one thinks of Occupy Wall Street—I'm broadly supportive—it has focussed public anger and changed the terms of the political debate, elevating issues such as bankers' pay, tax evasion by rich people, and corporate lobbying. That's all to the good. But from the White House's perspective, it has also had the unfortunate effect of sidelining a President vulnerable to the charge of cozying up to Wall Street and wary of giving the Republicans another cudgel to beat him with. (Think 1968, hippies/anti-war protestors, and Hubert Humphrey.)

Today, Obama gave his first considered response to O.W.S., and it was surprisingly positive. He even adopted some of the protestors' language, saying:

"I believe that this country succeeds when everyone gets a fair shot, when everyone does their fair share, and when everyone plays by the same rules. Those aren't Democratic or Republican values; 1% values or 99% values. They're American values, and we have to reclaim them."

Of course, Obama has talked before about rising inequality and falling tax burdens on the rich. (In the summer of 2010, he made a futile effort to rally support in Congress for ending the Bush tax cuts.) But what was new about today's speech was the acuteness and depth of Obama's analysis, and the way he turned it on the Republicans. Rising inequality isn't only morally repugnant, he said, it is economically inefficient and damaging to the country.

In what was a long speech, here are what I consider to be the six nut grafs:

"Look at the statistics. In the last few decades, the average income of the top one percent has gone up by more than 250%, to $1.2 million per year. For the top one hundredth of one percent, the average income is now $27 million per year. The typical CEO who used to earn about 30 times more than his or her workers now earns 110 times more. And yet, over the last decade, the incomes of most Americans have actually fallen by about six percent.

"This kind of inequality—a level we haven't seen since the Great Depression—hurts us all. When middle-class families can no longer afford to buy the goods and services that businesses are selling, it drags down the entire economy, from top to bottom. America was built on the idea of broad-based prosperity—that's why a CEO like Henry Ford made it his mission to pay his workers enough so that they could buy the cars they made. It's also why a recent study showed that countries with less inequality tend to have stronger and steadier economic growth over the long run.

"Inequality also distorts our democracy. It gives an outsized voice to the few who can afford high-priced lobbyists and unlimited campaign contributions, and runs the risk of selling out our democracy to the highest bidder. And it leaves everyone else rightly suspicious that the system in Washington is rigged against them—that our elected representatives aren't looking out for the interests of most Americans.

"More fundamentally, this kind of gaping inequality gives lie to the promise at the very heart of America: that this is the place where you can make it if you try. We tell people that in this country, even if you're born with nothing, hard work can get you into the middle class; and that your children will have the chance to do even better than you. That's why immigrants from around the world flocked to our shores.

"And yet, over the last few decades, the rungs on the ladder of opportunity have grown farther and farther apart, and the middle class has shrunk. A few years after World War II, a child who was born into poverty had a slightly better than 50-50 chance of becoming middle class as an adult. By 1980, that chance fell to around 40%. And if the trend of rising inequality over the last few decades continues, it's estimated that a child born today will only have a 1 in 3 chance of making it to the middle class.

"It's heartbreaking enough that there are millions of working families in this country who are now forced to take their children to food banks for a decent meal. But the idea that those children might not have a chance to climb out of that situation and back into the middle class, no matter how hard they work? That's inexcusable. It's wrong. It flies in the face of everything we stand for."

Maybe I'm wrong. But to me that seems like strong and cogent stuff. Doubtless, the Republicans will dismiss it as "class warfare." That is largely because they don't have anything more convincing to say. And anyway, Obama has already anticipated their response:

"It is wrong that in the United States of America, a teacher or a nurse or a construction worker who earns $50,000 should pay a higher tax rate than somebody pulling in $50 million. It is wrong for Warren Buffett's secretary to pay a higher tax rate than Warren Buffett. And he agrees with me .

"This isn't about class warfare. This is about the nation's welfare. It's about making choices that benefit not just the people who've done fantastically well over the last few decades, but that benefits the middle class, and those fighting to get to the middle class, and the economy as a whole."

Like many people who voted for Obama in 2008, I have been critical of some of his actions and inactions. What has bothered me most has not been any one thing in particular, but his overall failure to articulate and defend the vision of an activist government tackling market failures and protecting the public interest, which Teddy Roosevelt helped to create. Yes, the President has done some positive things and made some good speeches, and, yes too, he has faced enormous difficulties, but all too often his heart hasn't seemed to be in the fight.

Today, at last, he found his voice, or Teddy Roosevelt's voice. Either way, it was a big improvement.

Photograph by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers