John Cassidy's Blog, page 111

October 27, 2011

European Debt Deal: Two Cheers for Sarkozy and Merkel

Credit where it is due. Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarkozy, and their colleagues have averted disaster, at least for now, by cobbling together a deal that addresses some of the big issues driving the European economic crisis: Greek debt, fragile banks, and the potential for contagion to other countries, such as Spain and Italy.

But let us not get carried away. The European sovereign-debt crisis hasn't been resolved, and neither have the contradictions at the heart of the euro system that gave rise to it. Unless more fundamental reforms are carried out in the coming months, the best-case scenario for the continent remains one of grinding austerity for many more years.

First the good news. The immediate prospect of another global financial crisis on the order of what happened in 2008 has greatly receded. In persuading private investors to take a fifty per cent "haircut" on their holdings of Greek debt, and in forcing Europe's banks to raise more capital, if necessary in the form of public investments, Europe's politicians have demonstrated a capacity to act that many investors doubted they possessed. Hence today's rally on Wall Street and in other markets around the world.

In addition to lightening Greece's debt load and promising to shore up the banks, the European leaders agreed to scale up the European bailout fund, partly by using the sort of financial engineering I wrote about a couple of days ago and partly by bringing in new money, principally Chinese money. According to a story in the Financial Times, the Beijing government has already agreed in principle to invest up to €100 billion in the expanded European Financial Stability Facility, which could, in theory, be called on to provide Spain or Italy with the same sort of bailout it has already provided to Greece, Ireland, and Portugal.

That is all to the good. However, many details of the agreement remain to be resolved and implemented. Take the Greek debt deal. While a representative of Europe's banks has agreed to the principle of writing down the value of Greek debt by fifty per cent, negotiations with individual investors will take weeks or months to complete. By then, if recent history is a guide, the Greek economy will be even deeper in the hole, raising further doubts about its capacity to service its debt burden, which, even after this write-down, will come to about a hundred and twenty per cent of G.D.P.

The plan to expand the capital of the European bailout fund from €400 billion to more than €1 trillion is also far from finalized. Indeed, the European leaders didn't reveal anything more than what we already know: the European Financial Stability Facility will set up a special-purpose investment vehicle (S.P.I.V.) that will provide insurance to buyers of euro-zone debt.

When I say that the euro crisis isn't over, I mean that this package will not resolve the underlying problem that many countries apart from Greece have taken on debts they could have trouble financing. Italy is the prime example. Despite the celebrations in the world's stock markets, the interest rate on Italian government bonds didn't fall very far at all today, indicating that investors remain reluctant to lend to a country where economic growth has virtually stopped and the Berlusconi government seems to be permanently on the brink of collapse.

If the European Central Bank had firmly committed to lending member governments as much money as they need to see them through the crisis, this wouldn't matter. But it hasn't. Largely due to the fact that Germany effectively exercises a veto on all matters having to do with the central bank, today's agreement did nothing to resolve the ambiguity about its role in the crisis. As long as this ambiguity remains in place, speculators are unlikely to cease their attacks on euro-zone debt markets.

Ditto with the basic problem that got us into this mess: the ability of euro countries to enjoy the benefits of a monetary union and also pursue their own fiscal policies. That can't go on indefinitely. Barring an unforeseen blow-up, today's agreement means the euro will see out 2012 intact. But the prospects of the currency surviving beyond 2015 and 2020 depend upon fundamental reforms of European governance, involving substantial limits on national sovereignty, for which there is little or no public support.

Even after today's agreement, the Irish bookmaker Paddy Power had the odds that the Euro will break up by 2015 at 6/5, and the odds it will break up by 2020 at 4/7.

Photograph by Jean-Christophe Verhaegen/AFP/Getty

October 26, 2011

What's Happening in America?

Tear gas and violence on the streets of Oakland.

Congressional Budget Office Study shows income share of top one per cent has doubled since 1979.

CBS/New York Times poll shows two-thirds of Americans believe money and wealth is unfairly distributed and almost half support Occupy Wall Street.

Same poll shows ninety per cent of Americans have no faith in the political system to make the right decisions.

Herman Cain and Rick Perry propose giving the rich yet more tax cuts.

Wharton M.B.A. students chant "Get a job" to O.W.S. protesters.

Is this how the American class war begins?

Probably not, but Moises Naim surely has it right when he says: "The long, peaceful coexistence with income and wealth inequality is ending."

October 25, 2011

Rick Perry's Ugly Tax Hybrid: Not Flat, Not Fair, Not Credible

With time and public opinion running heavily against his stumbling, bumbling Presidential campaign—in the latest CBS/New York Times poll of Republican voters, he is down to six per cent—Texas governor Rick Perry today hoisted a Hail Mary pass high into the sky, hoping against hope it would land in a favorable spot. Blatantly attempting to steal some of the thunder from Herman Cain's "9-9-9" tax plan, Perry launched a rival flat-tax proposal of his own—or did he?

Even before Perry had formally unveiled his plan, at a factory in Greenville, South Carolina, critics were poking big holes in it—and those critics included some people on the right. "Rick Perry's tax-and-spending plan: Less than meets the eye?" asked Jennifer Rubin, a conservative blogger for the Washington Post. "Rick Perry's Tax Plan Would be a Disaster for America," trumpeted a headline on a column at FoxNews.com. (Yes, on FoxNews.com.) "It is an embarrassment," harrumphed Reihan Salam, of the National Review Online.

On the admittedly somewhat dubious principle that virtually anything Fox News and National Review commentators agree upon must be suspect, part of me was tempted to write a column pointing out the great virtues of Perry's plan. But having read the background materials his campaign has posted on his Web site, I couldn't do it. Whether you look at this proposal from the perspective of politics, economics, or ethics, it is a hideous clunker. If it doesn't mark the death rattle for Perry's candidacy, it certainly suggests that last rites could soon be necessary.

Let's do the politics first. Whatever you think of Cain's "9-9-9" plan—and as I've said repeatedly, I don't think it bears inspection—it is simple and snappy. Tear up the tax code. Tax workers, businesses, and consumers at nine per cent. That's it. (Actually, in response to criticisms, it's become a bit more complicated recently—but that was how it started out.)

Perry's plan, by contrast, keeps the current tax code in place but gives people the option of opting out of it and paying a flat tax of twenty per cent. This means that under President Perry—say it to yourself a few times and see how it sounds—there would be two tax systems, not one. Perhaps in Texas, that counts as simplifying the tax code and cutting out the army of accountants, tax experts, and other leeches who feed on the current system. Elsewhere, it would mean hiring an accountant to figure out what is the best deal for you. Perhaps it should be called the "H&R Block Plan."

The second problem with Perry's flat-tax plan is that, in common with virtually all such tax proposals, it is potentially horribly regressive. Why is this so? Let me turn you over to Bob Borosage, the president of the Institute for America's Future, a progressive think tank, writing at Politico: "If you pledge to lower the top rates of the income tax, raise the rates on the bottom to one rate and eliminate deductions, then, as night follows day, the rich pay less and working and middle-class people pay more. The higher number of poor people who are exempted from the tax, the higher the rate has to be on the rest."

And that is just the flat tax part of the plan. Perry is also proposing to abolish taxes on dividends, capital gains, and estates—all of which would greatly benefit the rich. Now, you might think a Presidential candidate proposing yet more big tax cuts for the rich would want to sugarcoat them in some way for everybody else. But if you think that, you don't know Perry. Asked on CNBC this morning whether he was concerned about the perception that his plan would generate millions of dollars in additional tax breaks for the wealthy, he replied:

"I don't care about that. What I care about is them having the dollars to invest in their companies, to go out and maybe start a business because they got the confidence again 'cause they actually get to keep more of what they work for. Those that want to get into the class warfare and talk about, oh my goodness, there are going to be some folks here who make more money out of this, or have access to more money, I'll let them do that."

O.K. Governor Rick. That's all right, then.

Careful readers will have noted that I said Perry's flat-tax plan is "potentially" horribly regressive. Because it is optional and because it would retain some deductions—for mortgage interest, charitable giving, and state and local taxes—it doesn't automatically qualify as your typical reward-the-rich/soak-the-middle-and-working-classes flat tax. The reward the rich part is certainly present. Investment bankers, film actors, and sport stars would face a marginal tax rate of twenty per cent rather than thirty-five per cent. But, theoretically at least, the ordinary American could avoid paying more taxes than he does now by choosing to remain within the old system.

When you think about it, in fact, the logic of the two-system approach leads to a conclusion that some might find reassuring. Under President Perry—try saying it again. After a while it sounds a bit less ridiculous—nobody would end up paying higher taxes than they do now. But since some folks (Jamie Dimon, Matt Damon, Albert Pujols) would end up paying considerably less, federal tax revenues would fall off a cliff. Unless, of course, the tax reform itself magically transformed the entire economy into high-growth, high-productivity Valhalla, thereby mushrooming the tax base—something like the Texas of Perry's dreams, perhaps. And that, as you might expect, appears to be the vision that underpins the plan. In Perry's words: "The flat tax will unleash growth."

With no details or projections to back it up, the Perry campaign says the hybrid income/flat tax would raise about eight per cent of G.D.P. and the overall tax system would raise about eighteen per cent of G.D.P., both of which are roughly in line with long-run averages. In the next few days, I would imagine, numerous non-partisan tax specialists will emerge to shred these claims and declare that Perry's plan, far from eliminating the budget deficit, would further balloon it. Unlike Cain, Perry is not proposing a national sales tax to make up some of the revenues that would be lost under his plans for the income tax. But even if we give Perry a pass and go with his numbers, they still don't add up. Federal spending is currently running at about twenty-five per cent of G.D.P. In the article on FoxNews.com I cited earlier, Peter Morici, an economist at the University of Maryland, pointed out that Perry's tax plan, "would require $900 billion in annual spending cuts, when the Congress is having trouble agreeing on an additional $100 billion."

Perry is promising to raise the retirement age for Social Security and Medicare, which would result in some real spending cuts, but not nearly enough to make his arithmetic work. Other proposals he has for Social Security, such as allowing younger workers to divert some of their payroll contributions to private accounts, would worsen the retirement system's deficit, at least in the short to medium term. (This is the transitional financing problem that the Bush Administration tussled with, to no avail, before abandoning its plans to reform Social Security.) Since Perry exempts the Pentagon from spending cuts, he is forced onto the hoary old path of slashing other forms of discretionary spending, such as science and education grants. (Not surprisingly, these cuts are unspecified.)

In short, Perry's tax plan is ill conceived and half-baked. It is too redolent of voodoo economics to be financially credible and too confusing to impress the voters. Taken together with the witless decision to try and resurrect the "birther" controversy over President Obama's American citizenship, it will only strengthen the perception that Perry is an overmatched Texan numskull. Somewhere up there on his campaign plane, Mitt Romney is smiling.

Photograph: Richard Ellis/Getty Images

Where Is the New Keynes?

On Monday, I was on Leonard Lopate's WNYC radio show talking about my recent article on John Maynard Keynes. (The piece is no longer behind a firewall. You can read it here, and listen to the interview here.) At the end of the show, Leonard asked me an interesting question: Has the financial crisis and Great Recession produced any big new economic ideas? My immediate response was that it hasn't, or, if it has, I wasn't aware of them. After the show, I thought about the question a bit more.

I still think the answer is no. There is nothing to compare with Keynesianism or Monetarism or even the so-called Washington Consensus of the nineteen-eighties and nineteen-nineties. Certainly, there is no new Keynes. But I do think that some important ideas have been discovered—or, rather, rediscovered. Here are six of them, together with some tips for further reading, one of which is rather self-serving:

1. Finance matters. This lesson might seem obvious to the man in the street, but many economists somehow managed to forget it. Two who didn't were Hyman Minsky and Wynne Godley, both of who were associated with the Levy Institute for Economics at Bard College. Minksy's now-famous "Financial Instability Hypothesis" can be found here, and one of Godley's warnings about excessive household debt can be found here. (It is from 1999!)

2. Credit busts are different from ordinary recessions. On this, the most widely quoted work is Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff's historical survey, "This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly," which details how debt overhang in the public and private sectors tends to produce "lost decades." For an old but still very readable account of how debt overhang can create deep recessions, I would recommend Irving Fisher's famous essay from 1933. For something more recent, I recommend this essay by Ray Dalio, the head of Bridgewater Associates, the world's biggest hedge fund.

3. Positive feedback and multiple equilibria have to be taken seriously. With the rise of rational expectations theory, the idea that financial markets and entire economies can spiral into bad outcomes—and for no very good reason—was relegated to a mathematical curiosity: so called "sunspots." Now, the notion is back, and for good reason. It appears to describe the world pretty well.

The role positive feedback played in amplifying the credit crisis of 2008 has been studied extensively, and this article by Princeton's Markus Brunnermeier provides a good survey. Turning to what is happening in Europe, Paul De Grauwe, of the Brussels-based Center for European Policy Studies, and Paul Krugman have both written interesting analyses of the Euro system from a multiple equilibrium perspective.

4. Especially in financial markets, self-regarding rational behavior isn't necessarily socially optimal. I wrote a lot about this in my book, "How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities." For those seeking a more technical analysis, I would recommend "Risk and Liquidity," by Princeton's Hyun Song Shin.

5. Monetary policy doesn't always work very well. This lesson should have been relearned in Japan. One person who did relearn it was Paul Krugman. This essay of his from 1998 explains how economies can get stuck in a "liquidity trap," and is still worth reading, as his book "The Return of Depression Economics," an updated version of which was reissued in 2008.

6. Fiscal stimulus programs don't provide a panacea for deep recessions, but the alternatives—do-nothing policies or austerity—are much worse. If you doubt this, I would suggest you look at what is happening in Greece and the United Kingdom, where austerity programs have been in effect for more than a year. As for the Obama stimulus, most serious studies show it did have a positive impact on G.D.P. growth and job creation—as detailed in this helpful post by Dylan Matthews on the Washington Post's Wonkblog.

Looking at this list, anyone familiar with Keynes will quickly realize that almost all of the points on it can be found in his writings, at least in embryo form. If economics is about building internally consistent models of toy economies from first principles, he wasn't a great economist. If it is about providing telling insights into how real economies function and malfunction, he still has few rivals. That is why he never goes away.

Endnote: Others will have different ideas about the lessons learned in the past few years. I'd be interested in seeing them. But please, spare yourself the effort of posting a comment to say that Keynesian stimulus programs don't work or that a return to the Gold Standard is our only salvation. Those are old canards, not new insights.

Keynes in 1925. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis.

October 24, 2011

Can Financial Engineering Save the Euro?

What is going on in Europe gets weirder and weirder.

With two days to go until the continent's leaders reach their self-imposed deadline for reaching an agreement on yet another "solution" to the long-running debt crisis, investors appear to be betting that all will be well. The U.S. stock market was up again on Monday morning. Since the start of October, when France and Germany conceded that urgent action needed to be taken, it has risen ten per cent.

To put it mildly, this appears to be a leap of faith.

Details of the likely agreement are beginning to emerge, and, lo and behold, it hinges on many of the things that got the global economy into this mess to begin with: leverage (borrowing), financial engineering, and a blizzard of confusing acronyms. It is as if some of the unemployed Wall Street geniuses who gave us S.I.V.s, C.D.O.s, and C.D.S.s had been hired by the European Union to work their magic on the debts of countries such as Greece, Portugal, and Italy.

The purpose of the new agreement is to boost the size of the European Financial Stability Facility (E.F.S.F.), a communal bailout fund that currently has about four hundred billion euros ($550 billion) in capital. This might sound like a lot of money, but some of it has already been committed to Greece, Ireland, and Portugal. With speculators now targeting Italy, which has about €1.9 trillion in debt, everybody agrees that the capital of the bailout fund needs boosting to at least a trillion euros.

The simplest way to do this would be for countries like Germany, France, and Belgium to put up more money, but there is no political support for such a move. An alternative solution, which Nicolas Sarkozy has championed, would be to turn the bailout fund into a bank, which would allow it to borrow from the European Central Bank. Since the E.C.B., like the Fed, has the power to print money, it could lend as much money as was needed to the E.F.S.F. to calm the markets. Unfortunately, this plan, too, ran afoul of politics. The Germans simply won't allow the central bank, which succeeded their beloved Bundesbank, to get near anything that looks like monetizing debts.

So what do you do when you need a large sum of money but you don't want to use your own? Place a call to your friendly investment banker, of course.

Under the current plan, the bailout fund would essentially be turned into an insurance company, but one that insures government bonds rather than autos and individuals. Heavily indebted European countries, such as Spain and Italy, would be able to buy insurance contracts from the E.F.S.F., which could be converted to cash if the bonds they were tied to defaulted. These contracts would be fully tradable, and the governments could then sell them to investors, which could thereby hedge their bond holdings.

If this scheme sounds vaguely familiar, it is because it is. The market for subprime mortgage securities worked in a very similar way. In that case, the insurers were A.I.G. and other "monoline" insurance companies, such as AMBAC, many of which are now bankrupt.

The other half of the plan would involve setting up another one of our old friends, a special-purpose investment vehicle, or S.I.V., to invest in European sovereign debt. Just like sub-prime S.I.V.s, the euro S.I.V. would have several tiers of capital: senior, mezzanine, and equity. The bailout fund would supply the equity tier, which would be first in line for any losses. Foreign countries, such as China and Brazil, as well as private investors, would be invited to invest in the senior and mezzanine tranches. According to an internal E.U. paper seen by Reuters, "The SPIV … would aim to create additional liquidity and market capacity to extend loans, for bank recapitalization via a member state and for buying bonds in the primary and secondary market with the intention of reducing member states' cost of issuance."

Will all this work? All along, my assumption has been that the European pols would fiddle and prevaricate until the very verge of disaster and then take the painful steps necessary to prevent the euro system from imploding. Now I am not so sure. In a column entitled "Europe is now leveraging for a catastrophe," Wolfgang Munchau of the Financial Times, one of the very best commentators on European matters, writes: "(T)he chances of a catastrophic accident is bigger than merely non-trivial. The main consequences of leverage will be to increase that probability."

October 21, 2011

Charting the Great Inequality Debate

On this week's Political Scene podcast, Dorothy Wickenden asked me why inequality has suddenly emerged as a live political issue. After ignoring the subject for years, even Republicans are being forced to address it. Eric Cantor, the House Majority Leader, is set to deliver a speech today about income disparity and ideas for promoting social mobility.

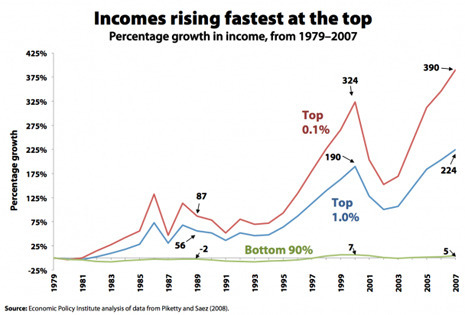

On one level, the answer to Dorothy's question is obvious: the reason inequality is a big deal is because it has risen so much. A new chart from Lawrence Mishel, of the liberal-leaning Economic Policy Institute, shows that between 1979 and 2007 people in the top one per cent of the economic pile saw their incomes double, whereas most everybody else hardly gained at all. (For those at the very, very top of the income distribution—the top 0.1 per cent—things were even better: their incomes quadrupled.)

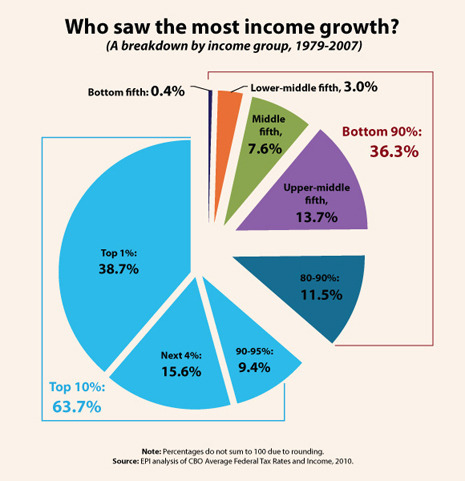

A second way to tell this story is to look at who gets to keep the extra dollars that the economy generates over the years as it expands. Mishel has produced another useful chart. It shows that between 1979 and 2007 almost two-thirds of all income growth (63.7 per cent) went to those in the top ten per cent of the income distribution. Very little of it—just eleven per cent—went to those in the bottom three-fifths of the income distribution (i.e. the majority of folks).

Looking at charts like these, the pertinent question isn't why Americans are increasingly concerned about inequality, but why they weren't marching in the streets years ago. The stagnation of wages and incomes for working-class and lower-middle-class Americans goes back to the nineteen-seventies, and the enormous gains at the top began in the nineteen-eighties.

It isn't as if nobody noticed what was happening. My first article about the subject appeared in 1995, and I was late to the game. Recently, I was re-reading a September 1992 piece in the American Prospect by Paul Krugman, which provided an excellent survey of developments up to that date. Rising inequality actually featured fairly prominently in the 1992 Presidential campaign. But with Bill Clinton's election, and particularly with the economic boom of the late nineteen-nineties, which lifted all boats, it gradually receded as a political issue.

Now it's back with a vengeance, and not just because of Occupy Wall Street. Even among middle-aged suburbanites who wouldn't dream of going down to Zuccotti Park the lopsided allocation of rewards in today's economy seems to be causing concern: hence the reaction of Cantor and other Republicans.

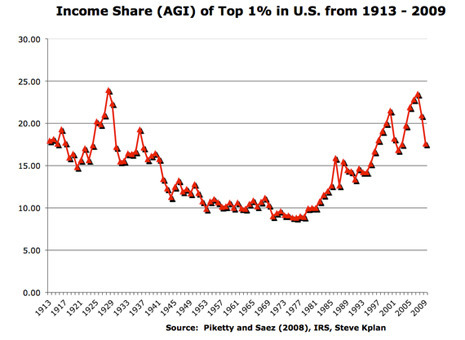

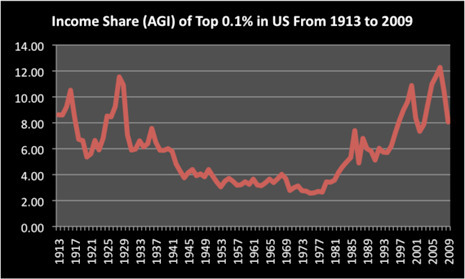

Ironically, this is happening when, strictly speaking, income inequality may well be falling, at least according to some commonly used measures. On her blog at TheAtlantic.com a couple of days go, Meghan McArdle presented two interesting charts based on some recent empirical work by Steven Kaplan, an economist at the University of Chicago. The charts show how the share of total income taken by the top one per cent of the income distribution and the top 0.1 per cent has changed over the decades. From 1973 to 2007, the lines rise steadily, except during recessions, when they fall back. In 2008 and 2009, the most recent year for which Kaplan could find figures, the lines fall back again, and quite steeply.

"I doubt Occupy Wall Street will be assuaged by learning that the top 0.1% now only receive 8% of the income earned in the US, even if that number is the lowest it's been since 2003," McArdle comments. Doubtless, she is correct on that. And the protesters have reason not to be assuaged. If the recent fall in income inequality were a permanent development, it would be big news indeed. But it is almost certainly a temporary artifact of the recession.

One of the biggest drivers of income inequality is the fact that so much of the nation's wealth—real estate, stocks, bonds, and physical capital—is concentrated in so few hands. (Other explanations include globalization, technical progress that is biased towards workers with extensive skill sets, the decline of trades unions, and changing social norms.) According to research by Ed Wolff, an economist at N.Y.U., in 2007, the latest year for which figures are available, the least-rich sixty per cent of American households (i.e. the majority of folks) owned just 4.2 per cent of the nation's net wealth—as defined to include 401(k) plans, I.R.A.s, mutual funds, and other savings vehicles used by the masses. ("Net" means the figures are net of debts owed.) The bottom forty per cent of households owned virtually none of the country's wealth (0.2 per cent).

So where is the wealth located? You guessed it. According to Wolff, the richest five per cent of American households own close to two-thirds (61.8 per cent) of the nation's net wealth—the richest one per cent own more than a third (34.6 per cent) of overall wealth. In good times, this capital generates a great deal of income in the form of interest payments, stock dividends, capital gains, and cash profits, which accounts for the stratospheric incomes of Warren Buffet and his buddies. But with the onset of the recession, these income streams fell back, limiting the share of overall income taken by the very rich. Hence the falling lines in McArdle's charts.

Now, it is certainly the case that Wolff's research doesn't take into account the recession, which has reduced the wealth of virtually everybody who has any, from struggling homeowners to stock-market billionaires. But while the overall amount of wealth has been slashed since 2007, there is little reason to suppose that its distribution has been markedly changed. And until the overall distribution of wealth becomes less concentrated, there is little prospect of income inequality, as measured by the share of the very, very rich, falling for good. (The other factors that have contributed to rising inequality, such as globalization and technical progress, aren't going away, either.)

"We don't want to spend years focused on income inequality, only to learn that the financial crisis fixed it for us," McArdle writes. Sadly, there is little danger of that happening. Rising inequality isn't a problem that will cure itself.

October 20, 2011

What They Don't Teach You at the Columbia School of Journalism

[image error]

My experience in this business has been somewhat bifurcated. It began in 1985, at the Columbia J-School, an institution that in those days took itself extremely seriously—and still does—as a promoter of responsible reporting and editing. For the past sixteen years, I have been at The New Yorker, where facts and fact-checkers, if not exactly sacred, are very highly valued. Between Columbia and Eustace Tilley, I spent several years working on Fleet Street and two years working at the New York Post, places where (how can I put it?) the devotion to the pursuit of absolute truth, and even a basic belief in the underlying concept, were a tad less firmly established.

Of course, I long ago left behind me the contemptible, disgraceful, and wholly-to-be-frowned-upon urges to take flyers, shape copy to fit screaming headlines, and otherwise indulge in the black arts of mass-market journalism. But I can still recognize an evil genius of the discipline when I see one, and none, in recent decades, have been more successful and controversial than Kelvin MacKenzie, a former editor of the London Sun, Britain's most popular newspaper, who was one of the latest witnesses to be called before the ongoing public inquiry that Lord Leveson, an eminent high-court judge, is carrying out into phone hacking at the News of the World and the broader issue of media regulation.

Long before the dawn of the cell phone, it was MacKenzie who turned the Murdoch-owned Sun, once a Labour-supporting publication, into a rabid, right-wing paper that trumpeted the xenophobic get-rich-quick values of Mrs. Thatcher's Britain, while mercilessly pursuing straying celebrities and other less deserving targets. During the Falklands War, when a Royal Navy submarine torpedoed an Argentinean cruiser, the Belgrano, with the loss of more than three hundred lives, MacKenzie ran the front-page headline "GOTCHA." In 1989, when ninety-six fans of Liverpool F.C. were killed in a terrible crush at a match in Sheffield, the Sun ran a still controversial story accusing other Liverpool fans of picking the pockets of the victims and urinating on cops trying to affect a rescue. In 1992, when the Conservatives defeated Neil Kinnock and Labour for a fourth consecutive victory, the Sun boasted, "IT'S THE SUN WOT WON IT." (One of MacKenzie's proteges at the paper was Piers Morgan, who went on to edit the News of the World before the phone hacking scandal, and now has a talk show on CNN.)

With McKenzie at the helm, the Sun was variously brutish, scabrous, outrageous, amusing, and terrifying. It enjoyed great commercial success, but not without one or two big setbacks. In 1987, it ran a front-page splash accusing Elton John of consorting with male prostitutes, only to be forced to apologize, pay damages, and disavow the story in humiliating fashion. Since quitting as editor, in 1994, MacKenzie has pursued various business and journalistic ventures. (He is currently a columnist on the Daily Mail, where he says his intention is to insult as many people as possible.)

True to form, MacKenzie didn't hold back when he appeared before the inquiry late last week. Some of what he said was self-serving and disingenuous. Dismissing the phone-hacking scandal as a localized outbreak of criminality, he questioned the very need for a public inquiry. Other comments MacKenzie made were painfully acute. At one point, he accused David Cameron, the British Prime Minister, of "obsessive arse kissing over the years of Rupert Murdoch." (MacKenzie added, "Tony Blair was pretty good, as was [Gordon] Brown. But Cameron was the daddy.")

What particularly caught my eye, though, was something MacKenzie said which received rather less attention—about fact-checking stories before publication. To my mind, at least, it could easily have come from the pages of Evelyn Waugh's 1938 novel "Scoop," still the classic fictional account of Fleet Street in action.

In preparation for his appearance before Lord Leveson, which was involuntary, MacKenzie received a list of questions. "Question seven basically wanted to know if an editor knew the sources of many of the stories," he said. "To be frank, I didn't bother during my 13 years with one important exception. With this particular story I got in the news editor, the legal director, the two reporters covering it and the source himself on a Friday afternoon.

"We spent two hours going through the story and I decided that it was true and we should publish it on Monday. It caused a worldwide sensation. And four months later The Sun was forced to pay out a record £1m libel damages to Elton John for wholly untrue rent boy allegations.

"So much for checking a story. I never did it again. Basically my view was that if it sounded right it was probably right and therefore we should lob it in."

Lob it in and stand well back: a handy maxim for tabloid terrorists everywhere.

But not one, I suppose, which will be making it onto the curriculum at Columbia and other J-schools anytime soon…

Kelvin MacKenzie, before giving evidence to the Leveson Inquiry. Photograph by Oli Scarff/Getty Images.

Occupy Wall Street: Who Are We?

For weeks, reporters, pundits, and political strategists have been puzzling over this question. Now, the organizers of the protest have provided at least part of the answer. A couple of weeks ago, they invited a CUNY sociologist, Héctor Cordero-Guzmán, to survey visitors to their main Web site, occupywallst.org. More than sixteen hundred people responded to Cordero-Guzmán's questionnaire. The results are particularly interesting because they get beyond the hard core activists in Zuccotti Park to people who support the O.W.S. protesters, but not to the extent of camping out with them.

Here are the main points, of Cordero-Guzmán's study (pdf):

Most of the respondents are young and well educated. Almost two-thirds of them (64.2 per cent) are under thirty-four, and more than nine in ten (92.1 per cent) are either in college or have graduated.

The respondents are overwhelmingly white (81.3 per cent).

Two thirds (67 per cent) are male. Nearly a third (30.4 per cent) are female. The other two per cent "preferred another gender designation."

Only half (50.4 per cent) work full-time. A fifth (20.4 per cent) work part-time. Roughly one-in-eight (13.1 per cent) are unemployed.

Nearly three quarters (71.5 per cent) earn less than $50,000 a year, and a quarter (24 per cent) earn less than $25,000 a year. Given that many of them are relatively young and don't work full-time, this is not really surprising.

Politically, seven in ten (70.3 per cent) regard themselves as independents. Roughly one in four (27.3 per cent) identified themselves as Democrats, and one in forty-two (2.5 percent) as Republicans.

How should these findings be interpreted? The O.W.S. organizers were keen to stress the fact that so many of their supporters are politically independent. "Occupy Wall Street is a post-political movement representing something far greater than failed party politics," they said in a post about the survey. "We are a movement of people empowerment, a collective realization that we ourselves have the power to create change from the bottom-up, because we don't need Wall Street and we don't need politicians."

That attitude clearly presents a challenge to politicians of both parties, but particularly the Democrats, who may be hoping to glom onto the movement. On the other hand, the O.W.S. organizers have welcomed the support of labor groups, such as the unions representing transit and health workers, which are closely associated with the Democratic Party. If O.W.S. endures, which I think it will, the question of how far it should engage with the mainstream political process, and particularly with President Obama's reëlection campaign, will loom ever larger.

Photograph by Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

October 18, 2011

Romney and Perry: The Title Bout

[image error]

Just when you were thinking that Rick Perry was about the most feeble, useless, lackluster political candidate you had seen since the East Texas oilman Claytie Williams, another big dumb Aggie, ran for the governorship of the Lone Star State back in 1990, the wounded armadillo picks himself up off the asphalt, shakes off the tire marks, and starts swinging big haymakers in the direction of Mitt Romney.

On being described as "a conservative of convenience," Romney managed to maintain the porcelain smile that he acquired a while ago in a reëducation camp for failed candidates run by Rudy Giuliani and Andrew Cuomo, two first-time losers who subsequently hit it big. (Why else did you think he spent more than three million dollars on consultants in the third quarter?) But when the reënergized Texan started mouthing off about him hiring illegal aliens and described his get-tough stand on immigration as "the height of hypocrisy," Romney flipped. His face reddened, his lips trembled, and, for a moment, it looked as if fisticuffs might ensue.

Alas, they didn't. But Romney was sufficiently rattled to show his unappealing side—the sneering, know-it-all, we're smarter than you dumb schmucks "Bainie" side—which he had been successfully covering up for months. After denying Perry's charges, which regurgitated an old story from the Boston Globe, he said mockingly: "It's been a tough couple of debates for Rick. I understand that." But Perry, with his poll ratings heading for the single digits, was too desperate and fired up for disdain to make any impression on him. "You stood up and did not tell the American people the truth," he insisted.

Welcome to the start of the Republican primaries proper: a no-holds-barred knockout contest between a former moderate Republican governor running as a born-again conservative and a former Democratic campaign manager running as a right-wing fruit cake. From a spectator's viewpoint, it's going to be lots of fun once Herman Cain gets out of the way, which he shows every intention of doing.

Suggesting to Wolf Blitzer that he could see himself trading every prisoner in Guantánamo Bay for a single American soldier probably wasn't the wisest way for Cain to have spent his pre-debate prep, but it paled besides what happened to him once the real talking started. The other candidates, led by Romney, subjected his "9-9-9" tax plan to a withering inspection, which it simply can't stand. When the history of Cain's campaign is written, sometime next month, probably, the killer blow will be seen to have come from the non-partisan Tax Policy Center, which on Tuesday released a study showing that eighty four per cent of Americans would pay higher taxes under Cain's proposal.

The person who stands to gain most from Cain's demise is Perry. Only a few days ago, he seemed headed for the knacker's yard. But when you are a former yell leader from Texas A. & M., you've got fifteen million dollars in the bank, and you have the backing of a Super PAC that is willing to spend another fifty million dollars on your campaign, you don't go down without a fight. So Perry is clawing and scraping for the conservative-Tea Party vote.

Shut down the United Nations; open up Central Park for oil drilling; lock up Ben Bernanke for treason. These appear to be some of the more moderate planks of Perry's platform. For some reason, he is currently striking a more centrist note on illegal immigration—perhaps because he actually has had to deal with the problem—but given the Nativist fever that is coursing through the Republican body politic, that seems unlikely to last. Before long, surely, he'll be signing up to Michele Bachmann's plan to build a fence from San Diego to Brownsville and Herman Cain's suggestion to electrify it.

As I said, the Romney-Perry battle is going to be entertaining to watch, especially for President Obama and his campaign managers. Saddled with a candidate whose disapproval rating in the daily Gallup tracking poll is now a stunning fifty four per cent, the first order of business for the Chicago brain trust is to put some blemishes on the likely Republican nominee. Negative advertisements can do some of this work, but self-inflected blows by the other side are far more effective.

Now that the gloves have come off, there are going to be a lot more of them.

Photograph by Ethan Miller/Getty Images.

Bell Rings for Title Bout between Romney and Perry: That's it for the Undercard

Just when you were thinking Rick Perry was about the most feeble, useless, lackluster political candidate you had seen since the East Texas oilman Claytie Williams, another big dumb Aggie, ran for the governorship of the Lone Star State back in 1990, the wounded armadillo picks himself up off the asphalt, shakes off the tire marks, and starts swinging big haymakers in the direction of Mitt Romney.

On being described as "a conservative of convenience," Romney managed to maintain the porcelain smile that he acquired a while ago in a re-education camp for failed candidates run by Rudy Giuliani and Andrew Cuomo, two first-time losers who subsequently hit it big. (Why else did you think he spent more than three million dollars on consultants in the third quarter?) But when the re-energized Texan started mouthing off about him hiring illegal aliens and described his get-tough stand on immigration as "the height of hypocrisy," Romney flipped. His face reddened, his lips trembled, and, for a moment, it looked fisticuffs might ensue.

Alas, they didn't. But Romney was sufficiently rattled to show his unappealing side—the sneering, know-it-all, we're smarter than you dumb schmucks "Bainie" side—which he had been successfully covering up for months. After denying Perry's charges, which regurgitated an old story from the Boston Globe, he said mockingly: "It's been a tough couple of debates for Rick: I understand that." But Perry, with his poll rating heading for the single digits, was too desperate and fired up for disdain to make any impression on him. "You stood up and did not tell the American people the truth," he insisted.

Welcome to the start of the Republican primaries proper: a no-holds-barred knockout contest between a former moderate Republican governor running as a born-again conservative and a former Democratic campaign manager running as a right wing fruit cake. From a spectator's viewpoint, it's going to be lots of fun once Herman Cain gets out of the way, which he shows every intention of doing.

Suggesting to Wolf Blitzer that he could see himself trading every prisoner in Guantanamo Bay for a single American soldier probably wasn't the wisest way for Cain to have spent his pre-debate prep, but it paled besides what happened to him once the real talking started. The other candidates, led by Romney, subjected his "9-9-9" tax plan to a withering inspection, which it simply can't stand. When the history of Cain's campaign is written, sometime next month, probably, the killer blow will be seen to have come from the non-partisan Tax Policy Center, which on Tuesday released a study showing that eighty four per cent of Americans would pay higher taxes under Cain's proposal.

The person who stands to gain most from Cain's demise is Perry. Only a few days ago, he seemed headed for the knacker's yard. But when you are a former yell leader from Texas A&M, you've got fifteen million dollars in the bank, you have the backing of a Super PAC that is willing to spend another fifty million dollars on your campaign, you don't go down without a fight. So Perry is fighting for the conservative-Tea Party vote.

Shut down the United Nations; open up Central Park for oil drilling; lock up Ben Bernanke for treason. These appear to be some of the more moderate planks of Perry's platform. For some reason, he is currently striking a more moderate note on illegal immigration—perhaps because he actually has had to deal with the problem—but given the Nativist fever that is coursing through the Republican body politic, that seems unlikely to last. Before long, surely, he'll be signing up to Michele Bachmann's plan to build a fence from San Diego to Brownsville and Herman Cain's suggestion to electrify it.

As I said, the Romney-Perry battle is going to be entertaining to watch, especially for President Obama and his campaign managers. Saddled with a candidate whose disapproval rating in the daily Gallup tracking poll is now a stunning fifty four per cent, the first order of business for the Chicago brains trust is to put some blemishes on the likely Republican nominee. Negative advertisements can do some of this work, but self-inflected blows by the other side are far more effective.

Now that the gloves have come off, there are going to be a lot more of them.

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers