John Cassidy's Blog, page 105

January 19, 2012

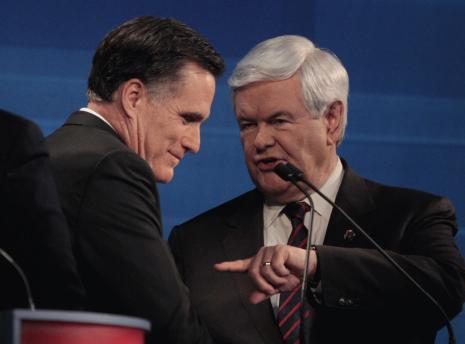

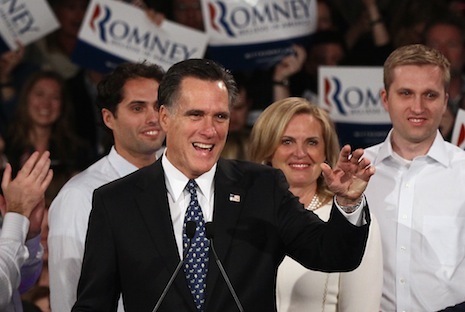

"Lazarus" Newt Set for Victory After K.O.'ing John King

Following one of the most bizarre twenty-four hour periods in American politics I can remember, Newt "Lazarus" Gingrich is seemingly heading for a stunning triumph in tomorrow's South Carolina primary—a victory that could well upend the race for the Republican nomination. Until a couple of days ago, Mitt Romney was on the verge of a quick victory, or at least that is what virtually every pundit in the country was saying. Now it looks like the contest could turn into a long, drawn-out slugfest between Mitt and Newt, with Ron Paul sitting in the peanut gallery.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves. The big news last night was Newt, at the very opening of the debate, throwing a carefully prepared tantrum aimed not just at moderator John King but also at CNN and the rest of the mainstream media for their having the temerity to ask about his ex-wife Marianne Gingrich's claim that, shortly before they split up, he asked her to partake in an "open marriage."

It was the question on everybody's mind, a question that Gingrich had most certainly been preparing for, and King opened the debate by turning to him and asking it straight out: Would he like to respond to his ex-wife's statements to ABC News?

"No, but I will," Gingrich snapped with the menacing stare of an aging gunfighter called upon to dispatch one more young foolish hood who thought he was faster to the draw. "I think the destructive, vicious, negative nature of much of the news media makes it harder govern this country. I am appalled that you would begin a Presidential debate on a topic like that

. To take an ex-wife and make it two days before the primary a significant question for a Presidential campaign is as close to despicable as anything I can imagine."

For Gingrich, blasting away at the media is his standard routine when facing scrutiny. Anybody who has covered him knows that this is how he behaves. He did it during previous debates, although not with this kind of venom, and he did it throughout the nineteen-nineties. But King and his producers seemed stunned by Newt's fusillade. Rather than standing up to Gingrich and pressing him about his ex-wife's allegations, which included the affirmation that he doesn't have the moral character to be President, King allowed him to dismiss them as unfounded ("Every personal friend in this period knows it was false") and get in a few more shots at CNN and the rest of the "élite media" for "defending Barack Obama by attacking Republicans."

With the crowd on its feet hooting and hollering like it was a football match, King once again passed up the obvious questions—"Are you calling your ex-wife a liar, Speaker Gingrich?" "How would your friends know what you said to her in a private conversation?" "If you are so concerned about privacy, why, during the Monica Lewinsky affair, did you insist on holding President Clinton to account for his personal life?"—King simply moved on to the other candidates, who also seemed too intimidated by the crowd reaction to put Newt on the grill. (Romney: "John, lets get onto the real issues, is all I've got to say.")

After that, the rest of the debate was a bit beside the point. Mitt got flustered, once again, by questions about his taxes. Rick Santorum scored some points on substance over Romney and Gingrich, reminding people that the latter, after four years as Speaker, "was thrown out by conservatives—there was a coup against him." Gingrich, veteran pol that he is, leavened his "grandiose thoughts"—his own description—with talk of more prosaic local matters, such as the need to upgrade Charleston's harbor. Paul quipped that he hadn't released his taxes yet because he was embarrassed by how poor he was compared to his rivals.

But none of that mattered very much compared to what had happened earlier. John King and CNN hadn't won the primary for Gingrich, but by giving him the stage unimpeded—a moment Jeff Greenfield, via Twitter, instantly compared to Ronald Reagan's famous statement during his 1980 debate with George H. W. Bush: "I am paying for this microphone!"—they had helped him not to lose it.

Even before the debate, even before Rick Perry's dramatic decision earlier in the day to bow out and endorse Newt, three different polls—from Rasmussen, Insider Advantage, and Public Policy Polling—had showed the former Speaker surging past Mitt. The first survey showed him leading by two points, the second by three points, and the third by six points. Most of the questioning for these polls had been carried out on Wednesday.

Evidently, Newt's pontificating and use of racially coded language during Monday's debate, Romney's problems with his taxes, or some combination of the two, impressed Republicans in the Palmetto State. The Rasmussen poll showed Gingrich going from fourteen points behind Mitt before Monday's debate to two points ahead of him on Wednesday. "Newt has all the momentum in South Carolina now," Dean Debman, the president of Public Policy Polling, said before last night's debate. "The big question now is whether ABC's interview with his ex-wife will stop it."

As of early this morning, it hadn't. At Intrade, an online-betting site where people can speculate about the outcomes of political races, Newt had moved past Mitt to become the firm favorite. At 2 A.M., Intrade was putting the probability of Newt winning South Carolina at sixty-six per cent and the probability of Mitt winning at thirty-four per cent. (A few days ago, the weight of money was saying Romney's odds of winning were over ninety per cent.)

Some Republican strategists are already looking ahead, beyond Saturday, to a race transformed. "If Newt surge continues, you have 3 diff winners in IA, NH, and SC, which has never happened before," Ralph Reed, chairman of the Faith and Freedom Coalition, tweeted yesterday. "Wow."

Wow is right.

If there is a message in all this, it is this: don't listen to the pundits, don't count your chickens, and don't underestimate Newt. He might be a blowhard, a man of questionable morals, a corporate tool, and a race baiter, but he can handle himself in a street fight and he knows how to rile up the G.O.P base, especially in the South. He's been doing it, as he frequently reminds us, for almost forty years.

AFP Photo/Emmanuel Dunand.

"Lazarus" Newt Set for Victory After Knocking out John King

Following one of the most bizarre twenty-four hour periods in American politics I can remember, Newt "Lazarus" Gingrich was seemingly heading for a stunning triumph in tomorrow's South Carolina primary—a victory that could well upend the race for the Republican nomination. Until a couple of days ago, Mitt Romney was headed for a quick victory, or at least that is what virtually every pundit in the country was saying. Now it looks like the contest could turn into a long, drawn out slugfest between Mitt and Newt, with Ron Paul sitting in the peanut gallery.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves. The big news last night was Newt, at the very opening of the debate, throwing a carefully-prepared tantrum aimed not just at moderator John King but also at CNN and the rest of the mainstream media for their having the temerity to ask about his ex-wife Marianne Gingrich's claim that, shortly before they split up, he asked her to partake in an "open marriage."

It was the question on everybody's mind, a question Gingrich had most certainly been preparing for, and King opened the debate by turning to him and asking it straight out: Would he like to respond to his ex-wife's statements to ABC News?

"No, but I will," Gingrich snapped with the menacing stare of a retired gunfighter called upon to dispatch one more young foolish young hood who thought he was faster to the draw. "I think the destructive, vicious, negative nature of much of the news media makes it harder govern this country. I am appalled that you would begin a presidential debate on a topic like that

To take an ex-wife and make it two days before the primary a significant question for a presidential campaign is as close to despicable as anything I can imagine."

For Gingrich, blasting away at the media is his standard routine when facing scrutiny. Anybody who has covered him knows this is how he behaves. He did it during previous debates, although not with this kind of venom, and he did it throughout the 1990s. But King and his producers seemed stunned by Newt's fusillade. Rather than standing up to Gingrich and pressing him about his ex-wife's allegations, which included the affirmation that he doesn't have the moral character to be president, King allowed him to dismiss them as unfounded ("Every personal friend in this period knows it was false.") and get in a few more shots at CNN and the rest of the "elite media" for "defending Barack Obama by attacking Republicans."

With the crowd on its feet hooting and hollering like it was a football match, King once again passed up the obvious questions—"Are you calling your ex-wife a liar, Speaker Gingrich?" "How would your friends know what you said to her in a private conversation?" "If you are so concerned about privacy, why, during the Monica Lewinsky affair, did you insist on holding President Clinton to account for his personal life?"—King simply moved onto the other candidates, who also seemed too intimidated by the crowd reaction to put Newt on the grill. (Romney: "John, lets get onto the real issues, is all I've got to say.")

After that, the rest of the debate was a bit beside the point. Mitt got a bit flustered, once again, by questions about his taxes. Rick Santorum scored some points on substance over Romney and Gingrich, reminding people that the latter, after four years as Speaker, "was thrown out by conservatives—there was a coup against him." Gingrich, veteran pol that he is, leavened his "grandiose thoughts"—his own description—with talk of more prosaic local matters, such as the need to upgrade Charleston's harbor. Paul quipped that he hadn't released his taxes yet because he was embarrassed by how poor he was compared to his rivals.

But none of that mattered very much compared to what had happened a bit earlier. John King and CNN hadn't won the primary for Gingrich, but by giving him the stage unimpeded—a moment Jeff Greenfield, via Twitter, instantly compared to Ronald Reagan's famous statement during his 1980 debate with George H.W. Bush: "I am paying for this microphone!"—they had helped him not to lose it.

Even before the debate, even before Rick Perry's dramatic decision earlier in the day to bow out and endorse Newt, three different polls—from Rasmussen, Insider Advantage, and Public Policy Polling—had showed the former Speaker surging past Mitt. The first survey showed him leading by two points, the second by three points, and the third by six points. Most of the questioning for these polls had been carried out on Wednesday.

Evidently, Newt's pontificating and use of racially coded language during Monday's debate, Romney's problems with his taxes, or some combination of the two, impressed Republicans in the Palmetto State. The Rasmussen poll showed Gingrich going from fourteen points behind Mitt before Monday's debate to two points ahead of him on Wednesday. "Newt has all the momentum in South Carolina now," Dean Debman, the president of Public Policy Polling, said before last night's debate. "The big question now is whether ABC's interview with his ex-wife will stop it."

As of early this morning, it hadn't. At Intrade, an online betting site where people can speculate about the outcomes of political races, Newt had moved past Mitt to become the firm favorite. At 2 a.m., Intrade was putting the probability of Newt winning South Carolina at 66 per cent and the probability of Mitt winning at 34 per cent. (A few days ago, the weight of money was saying Romney's odds of winning were over ninety per cent.)

Some Republican strategists are already looking ahead, beyond Saturday, to a race transformed. "If Newt surge continues, you have 3 diff winners in IA, NH, and SC, which has never happened before," Ralph Reed, chairman of the Faith and Freedom Coalition, tweeted yesterday. "Wow."

Wow is right.

If there is a message in all this, it is this: don't listen to the pundits, don't vote Republican, and don't underestimate Newt. He might be a blowhard, a man of questionable morals, a corporate tool, and a race baiter, but he can handle himself in a street fight and he knows how to rile up the G.O.P base, especially in the South. He's been doing it, as he frequently reminds us, for almost forty years.

AFP Photo/Emmanuel Dunand.

Yippee! Perry's Grenade Shakes Up Mr. Inevitable

Who said this thing was over?

Since nobody else is likely to do it, I'd like, on behalf of the campaign-media scrum, to issue a heartfelt thank you to Rick Perry. You just made the Republican primaries interesting again. By withdrawing from the race and endorsing Newt Gingrich on the eve of the pivotal South Carolina primary, the Texas Governor has tossed a live grenade into the lap of Mitt Romney, stopping, at least for now, all the talk about the inevitability of his candidacy.

With tonight's CNN debate in Charleston just hours away, it would be foolish to reach any firm conclusions about where things go from here. All that is certain is that nothing is quite certain anymore. Even before Perry's move, Gingrich was gaining in the South Carolina polls and cutting into Romney's lead. Now, some seasoned strategists, such as Ed Rollins, think Newt can go on and win Saturday's primary, which would mean that "Mr. Inevitable" would have lost two out of three states. (In other news today, it looks like Rick Santorum may have won the Iowa caucus, by thirty-four votes.)

Say what you like about Perry—and I've said quite a bit, none of it flattering—he keeps things lively. From the first press availability of his campaign, when he suggested the Fed's Ben Bernanke was a traitor, to his final debate, in which he called the prime minister of Turkey an Islamic terrorist and defended the Marines who desecrated the corpses of Afghans said to be Taliban fighters, "Mr. Oops" has been a dear friend to reporters and commentators alike—not to mention ordinary Americans looking for confirmation that, in a world of increasing blandness and conformity, there are still, out there in the wilds of Texas and other places, some crazy and untamed beasts who could never be mistaken for inhabitants of other lands.

Even today, in his withdrawal speech, which he delivered from a hotel conference room in Charleston, Perry managed to mangle his message. Citing the Texan legend Sam Houston as his inspiration, he said, "I know when it is time to offer up a strategic retreat," and offered up this testimonial to the man he was urging voters to support for the White House. "Newt is not perfect, but who among us is? The fact is there is forgiveness for those who seek God. And I believe in the power of redemption, for it is a central tenet of our faith."

If that was meant to be a compliment, it was a slightly peculiar one. It sounded rather as if Perry had got an advance peek at ABC's upcoming broadcast of its interview with Newt's second wife, Marianne, in which, she says he lacks the moral character to be President, instancing the occasion, towards the end of their time together, when he asked her to share him with his then mistress (and now wife) Callista in an "open marriage."

How the evangelical voters of South Carolina will react to this saucy revelation remains to be seen. Perry did add that Gingrich was "a conservative visionary who can transform America," a man with "the ability to rally and captivate the conservative movement," and "the courage to tell the Washington interests to take a hike." (With all these things going for him, is it so surprising that Newt could come to the conclusion that he had enough love for two women?)

Marianne Gingrich's ill feelings towards Newt aren't exactly news, either. Early last month, when Newt was leading the polls, I wrote about a 2010 profile in Esquire that contained some similarly incendiary comments from her. The ex-wife bomb was going to explode in Newt's face at some point, and Perry's endorsement did a good job of relegating it to the second story of the day—or third if you count the news from Iowa. (Note to Justin Wolfers, the Wharton economist who bet me via Twitter that my prediction of a Santorum victory would turn out wrong: thanks for graciously conceding defeat!) Still, Newt is going to have to react to the ABC interview, and in a fuller manner than he did this morning, when, speaking on NBC, he criticized ABC News for "intruding into family things that are more than a decade old," and adding, "I'm not going to say anything negative about Marianne."

As for Mitt, he has sent for help from the U.S Cavalry. It has arrived in South Carolina in the form of John Sununu, the former Governor of New Hampshire, and Peter King, the Congressman from Long Island. Sununu, who during the Iowa primary suggested that Gingrich was mentally unstable, today directed reporters to the censure he received for ethical abuses when was Speaker of the House, saying it "reflects on his ability as a leader." King, for his part, did his best to portray Newt as a hysterical drama queen, saying, according to Politico, "If by some chance he was elected president, then for the country's sake, we would be constantly trying to get ourselves out of crisis that Newt created."

To be sure, Newt has some issues relating to self-discipline and self-control. But the fact that Romney felt it worthwhile to fly in two surrogates to point them out again shows that he was worried. And that decision was taken before Perry's bit of theatre, which, for all its eccentricities, added quite a bit to Newt's momentum. By 2:30 P.M. Thursday, on Intrade (the online betting market), the implied probability of Newt winning the South Carolina primary had shot up to forty-one per cent.

Stay tuned. The next forty-eight hours could be something.

Photograph by Allison Joyce/Getty Images.

January 17, 2012

The Politics and Economics of Mitt's Fifteen Per Cent Tax Rate

The other day, when I was listing some positive things about Mitt Romney, I forgot to include an important one: through his candidacy and his background at Bain Capital, he has helped to stimulate a growing debate about equity, inequality, and who gets what in today's economy.

Take the news that Romney, after months of avoiding the subject, has finally revealed something embarrassing about his tax situation. "What's the effective rate I've been paying?" he said at a press conference on Tuesday morning in Florence, S.C. "It's probably closer to the fifteen per cent rate than anything."

So there you have it. What many people had suspected is true. The Mittster, like Warren Buffett and some other billionaires, has been paying a smaller proportion of his income in federal taxes than many ordinary Americans who live on modest wages.

Buffett, you may recall, has described this situation reprehensible and called for it to be changed. In a boffo op-ed for the New York Times last summer, he wrote, "While the poor and middle class fight for us in Afghanistan, and while most Americans struggle to make ends meet, we mega-rich continue to get our extraordinary tax breaks These and other blessings are showered upon us by legislators in Washington who feel compelled to protect us, much as if we were spotted owls or some other endangered species."

The entire Republican Party, Romney included, has defended the current system to the hilt, arguing that low taxes on rich people are necessary to reward risk-taking and entrepreneurship. Romney didn't go that far in his press conference, but he made it clear that the reason he pays so little to the federal government is because he exploits some of the loopholes that Buffett was talking about. Indeed, the evidence suggests that Romney benefits from not one tax break but two—the first questionable, the second unconscionable.

One advantage Mitt enjoys is that some of his income comes from cashing in profitable investments, which are taxed at just fifteen per cent. "Because my last 10 years, I've my income comes overwhelmingly from some investments made in the past, whether ordinary income or earned annually," he said this morning. "I've got a little bit of income from my book, but I gave that all away. And then I get speakers' fees from time to time, but not very much."

But the fifteen per cent tax rate on capital gains isn't the full story—far from it. If it were, Romney and the Republicans would have rather less to worry about. Over the last fifteen years, both parties have supported lower taxes on investment income. It was Bill Clinton, in 1997, who cut the capital gains tax from twenty eight per cent to twenty per cent. George W. Bush reduced it to fifteen per cent.

Personally, I have never been fully persuaded by the arguments for lower taxes on capital income, many of which emerged from the work of Harvard's Martin Feldstein, who headed the Council of Economic Advisers under Ronald Reagan. The goal of cutting such taxes is to raise investment and productivity. But investment and productivity both rose faster during the 1960s and 1970s, when dividends and capital gains were taxed at the same rate as income. Still, at least for a while, both parties went along with Feldstein's argument. (Larry Summers, who was Secretary of the Treasury under Clinton, did his thesis under Feldstein.)

The bigger problem for the Republicans is the second tax break that Romney benefitted from—a loophole designed exclusively to benefit a very small group of extremely rich men and women: hedge fund managers and private equity managers. As the New York Times revealed last month, Romney, despite the fact he "retired" from Bain Capital in 1999, still receives a share of the firm's profits, or he did so until very recently. As a practical matter, Romney hasn't worked for the firm for many years. But for the purposes of his personal finances and his dealings with the I.R.S., he has been very much engaged in the private equity industry.

One reason private equity fund managers like Romney get so rich is that they charge their investors outlandish fees: an annual levy equivalent to two percent of their investment, plus twenty per cent of any profits they make. That's hard to justify, but it's a matter between consenting adults. If pension funds and other investors are silly enough to pay through the nose for investment exposures they could obtain much more cheaply in other ways—principally by borrowing money on their own account and leveraging up their investments—there isn't much that can be done to stop them.

Far more important from a public policy point of view is the tax law that unfairly advantages the hedge fund/private equity managers. When a hedge fund manager/private equity manager deducts a twenty per cent share of his investor's profits and puts it in his firm's bank account, he doesn't classify it as fee income: he classifies it as investment income—"carried interest" it is called in the trade—which allows it to be taxed at the fifteen per cent rate. From an economic perspective, this makes no sense. The person (or institution) putting capital at risk is the investor, not the fund manager, which in this case is Bain Capital. Since the fifteen per cent tax rate is designed to encourage risk taking, it clearly shouldn't apply to the manager's fees. They should be classified as ordinary income and taxed as such. But they aren't, and never have been.

How have Romney and his buddies gotten away with this scam for so long? Wisely, they didn't broadcast its existence, and politicians from both parties, hungry for their campaign donations, were willing to ignore it. But as the hedge fund and private equity industries got bigger and bigger over the past two decades, the taxes lost as a result of the loophole—some twenty billion dollars a year for the private equity industry alone—could no longer be ignored. In 2007, Congressman Sandy Levin, a Michigan Democrat, put forward legislation that would have tightened up the "carried interest" exemption, but the Republicans blocked it. And since then, several other reform efforts have foundered.

None of this is new, of course. Experts on tax law and economists interested in inequality have been writing about the carried interest deduction for years. What is news is Romney's emergence, with the all baggage he is carrying, as the Republican front-runner. From his role at Bain Capital, to his personal finances, to his calls for even more tax cuts skewed towards the rich, he puts a human face on what has happened to the American economy over the past twenty-five years.

Over the coming months, we shall see how the American public reacts to this face. As my colleague George Packer noted in a sharp comment this morning, the Obama administration appears to be intent on making rising inequality a central campaign issue. Much as I support this strategy, it isn't without risks.

Although Obama has repeatedly called for the elimination of the hedge fund/private equity loophole, he hasn't exactly made it a priority of his administration—a decision that may not be wholly unrelated to the fact that the hedge fund industry was one of the biggest sources of donations to his 2008 campaign. Even today, Obama is raising money from hedge funds, private equity funds, and other financial firms, although with rather less success than in 2008. According to OpenSecrets.org, among the top ten contributors to his 2012 campaign there is only one financial firm, Chopper Trading, which is based in Chicago.

When it comes to toadying up to rich campaign contributors, neither party is guilt free. But Obama and the Democrats have come out in favor of allowing the Bush tax cuts for the rich to sunset at the end of 2012, eliminating the carried interest loophole, and enacting the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill. Mitt and the Republicans are against all of these things. Will this hurt them come November, and, if so, how much? It will be fascinating to see.

Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.

January 16, 2012

S.C. Debate: Mitt Survives Mugging; Perry Goes Postal

And then there were five.

Jon Huntsman's podium having been hastily removed from the stage of the Myrtle Beach Convention Center, the remaining candidates went right at it, the logic of the race dictating their tactics. With Romney in a seemingly unassailable lead, Gingrich and Santorum, his two most plausible challengers, were tasked with effecting a knockout. Mitt, naturally enough, was intent on avoiding such an outcome. Ron Paul, as usual, was driven largely by his own concerns. And Perry—well, it is never very clear what he's up to, but I'll get to that later.

Two hours later, Romney, despite being shaken up once or twice, was still on his feet. It wasn't his best debate. Early on, it looked like it might be his worst. But he absorbed some heavy blows, swayed out of the way of others, and came back stronger at the end. To the extent that the basic narrative of the race remained unchanged, he was the winner. But it was the victory of a man who had narrowly survived an attempted mugging.

Perhaps the best news for Mitt was that neither Gingrich nor Santorum had a bad night. If one of them had really messed things up, his supporters might have coalesced around the other. But that didn't happen. Gingrich, as has often been the case in these debates, was impressive. Santorum, sporting a weekend endorsement from the high priests of what used to be called the Moral Majority, also had his moments—enough of them, certainly, to prevent a mass exodus of his supporters. So Mitt ended the night, as he started it, with a hopelessly divided opposition.

The debate began, as expected, with Bain Capital. This being a Fox News event, the questioner, Brett Baier, framed the issue by asking Newt Gingrich to justify attacking free market capitalism, which he did quite handily, I thought. "I don't think raising questions is solely a prerogative of Barack Obama," Newt said, adding that in some of the companies Bain invested in there seemed to be a pattern of saddling them with huge debts and driving them into bankruptcy. That, he said, was "something he"—Romney—"should answer."

Not for the last time, Romney looked uncomfortable. Some companies that Bain invested in created jobs, he said. Others weren't as successful and shed jobs—"The record is pretty much available for people to look at." That was a stretcher, but before Romney could congratulate himself on getting away with it, Rick Perry was demanding that he turn over his tax returns before Saturday's vote, saying in his slow Texas drawl: "Mitt, we need for you to release your income tax records so we can see how you made your money."

Since the night of the New Hampshire primary, I and many other people had been wondering why Perry had stayed in the race. Now we had our answer. He was here to bring down Mitt, whom he sees, with some justification, as the representative of the Washington-based party establishment, and, in particular, of Karl Rove, with whom he has a long-standing feud rooted in Texan politics. "I hope you will" release your tax returns he went on, looking directly at Romney, "so the people of South Carolina can see if we have a flawed candidate."

This time, Romney didn't even pretend to address the question. But when Kelly Evans, of the Wall Street Journal, repeated it, he couldn't escape. As he sometimes does when he's flustered, he started talking faster and rambling. First he said that he'd already published a lot of financial information and wasn't planning on releasing his taxes. Then he said other presidential candidates had released their taxes around the April tax deadline; then, "I'm happy to do that." Finally, he said; "I'm not opposed to do that. Time will tell."

In Mittspeak, this appeared to be a reluctant acknowledgement of the inevitable: he'll have to let the American people know what he earns and how much (or how little) he pays in taxes. Of course, the way things are going he will have the nomination locked up well before the middle of April. With the evening threatening to turn into a Mitt roast, this may not have seemed like much consolation. Santorum even managed to pin him from the left, asking him whether he supported restoring the voting rights to felons who had served their sentences, done their probation, and re-entered the community. Eyeing his tough-on-crime southern audience, he said he opposed voting rights for felons, but Santorum then forced him to admit that he hadn't done anything as governor of Massachusetts to overturn a law allowing felons to vote even before they had served out their parole.

Mercifully for Romney, the debate eventually turned to less contentious subjects for a Republican audience, such as how far the top rate of income tax—currently thirty-five per cent—should be reduced. Santorum said the rate should be twenty-eight per cent, Romney said twenty-five per cent, Perry said seventeen per cent, and Gingrich said fifteen per cent. Paul, bless his heart, topped them all, saying: "In 1913, it was zero per cent. What's so bad about that?"

When it came to the killing of Osama Bin Laden, the bidding went in the opposite direction. Paul questioned the wisdom of extra-judicial killings, suggesting that Bin Laden, like Saddam Hussein, could have been captured and put on trial. Gingrich, citing as his authority Andrew Jackson, said the appropriate stance toward enemies of the United States was "Kill them." Romney, not to be outdone, supplemented the Gingrich/Jackson with a geographic directive, "We go anywhere and kill them," adding, just in case anybody had missed his message, "The right thing for Osama Bin Laden was the bullet in the head he received." With many members of the audience sounding as if they had taken full advantage of Myrtle Beach's extended happy hour, Romney evoked loud cheers with those lines.

Gradually, Romney seemed to regain some of his poise. He gave a well thought-out answer on Social Security reform, a politically astute (though morally bankrupt) answer on illegal immigrants—"return home, apply, get in line with everybody else"—and an utterly brazen but quite effective one on Super PACs, in which he lamented not having control over negative ads put out in his name. (To which, Buddy Roemer, who is still in the race but who hasn't been invited to any of the debates, replied via Twitter: "Mitt, you're full of crap. Your campaign staffers left specifically to start your Super PAC.")

Finally, it was over. The candidates left the stage to talk up their performances; some of the audience (but not Romney's Mormon contingent) presumably headed for the bars and jiggle joints that festoon this getaway; and the rest of us were left with one nagging question. Had Rick Perry, in the midst of an almost incoherent rant about the Middle East, really accused Recep Erdogan, the highly respected Turkish prime minister, of being an Islamic terrorist, and suggested that Turkey, a long-standing U.S. ally, should be ejected from NAT0?

The transcript showed that he had done so, or as good as, anyway.

Baier: "Do you believe Turkey still belongs in Nato?"Perry: "Obviously when you have a country that is being ruled by what many would perceive to be Islamic terrorists, when you start seeing that type of activity against their own citizens, then, yes Not only is it time for us to have a conversation about whether or not they belong to be in NATO but it's time for the United States, when we look at their foreign aid, to go to zero with it."

You couldn't make this stuff up. I'm telling you.

(Photograph: Charles Dharapa-Pool/Getty Images)

Good Riddance to Jon Huntsman

Watching Jon Huntsman announcing his withdrawal from the race this morning, it wasn't hard to predict what his political obituaries would say: some of them had already been written. "Jon Huntsman's strategy just wasn't made for these times," said a headline in today's Los Angeles Times. "He is out-of-step with the anger that has overwhelmed his party and puts it at odds with the vast, sensible mainstream of this country," Joe Klein wrote on Time.com during the New Hampshire primary. " a conservative party that doesn't take Huntsman seriously as a candidate has truly lost its way."

That's surely the impression Huntsman would like to leave behind: the reasonable man in an unreasonable world; a business-oriented, pragmatic conservative who tried to talk sense, and, when it didn't work out, left the stage early, his dignity and worldview intact. "This race has degenerated into an onslaught of negative and personal attacks not worthy of the American people and not worthy of the American people in this critical time in our nation's history," he declared with his family standing behind him. And he went on: "I call on each candidate to cease attacking each other and instead talk directly to the American people."

At which point, I could almost hear the cheering from the editorial floor of the New York Times. If the electorate in the Republican primaries consisted of the editorial staff of the Times, Time, or practically any other major publication, The New Yorker included, Huntsman would have won in a canter. Indeed from the very beginning, mainstream media commentators had been his biggest supporters: Marc Ambinder wrote on theAtlantic.com back in 2009: "Huntsman is presidential quality timber." Mark Halperin said on MSNBC last June; "he's got the second best chance to be the nominee right now, after Mitt Romney."

Forgive me if I never shared either of those assessments. When I first started writing about the Republican primaries, last fall, I couldn't for the life of me understand why Huntsman was a participant, unless he was there to serve as Romney's mini-me. Wasn't there already a business-oriented, pragmatic conservative in the race? And wasn't this candidate a Mormon who, before going into business, had spent times overseas as a missionary, seeking to convert the natives to a life of abstinence? And didn't this fellow also have an "Obama problem" that was likely to alienate him from at least some conservative voters?

These questions could be combined into one: With Romney in the race and leading it, what was the point of Huntsman?

Despite picking up plenty more favorable articles as he went along, Huntsman never provided a convincing answer to this question. He retained his status as the mainstream media's Jesus candidate whilst demonstrating he wasn't up to the job. In the words of Fergus Cullen, a former chairman of the New Hampshire Republican Party, who endorsed Huntsman, to Beth Rainard, of the National Journal: "There was no edge to his message, no contrast with other candidates, and he was way too subtle. I appreciated his civility a lot, but I concluded that fundamentally, he's a diplomat and not a politician.''

Could things have played out differently? With Romney occupying the center-right ground, Huntsman never had a realistic chance of winning the nomination when he entered the race last year. But he did have choices to make. As a successful governor of Utah, he had combined economic conservatism (he introduced a flat tax and presided over the creation of a lot of jobs) with progressive approaches in other areas (he endorsed efforts to tackle global warming, supported a raise in the minimum wage, and relaxed Utah's drinking laws). As a presidential candidate, should he emphasize his moderate credentials or his conservative ones? He chose the latter option. And that, I think, is when he doomed his candidacy to irrelevance. With Bachmann, Cain, Gingrich, Perry, and Santorum all vying for the same voters, and with Romney busy tacking to the right at every opportunity, the field on the right was simply too crowded to accomodate anybody else, especially an anybody who had just spent two years working for the Obama administration.

At least the outlines of a different strategy were on offer. With a bit of imagination, and some of his father's money, Huntsman could have marketed himself as the moderate rival to Romney: a pro-government Teddy Roosevelt Republican who favored cracking down on Wall Street, ending the war in Afghanistan, engaging with the Chinese, eliminating tax loopholes for the rich and powerful, and using federal investments to stimulate economic growth. Such a platform wouldn't have endeared Huntsman to conservatives: So what? They already had too many candidates to choose from. By positioning himself as an opponent of vested interests and a vocal defender of government intervention where it is needed, he could have staked out a position as the heir to the tradition of moderate Republicanism—the Republicanism of Teddy, Ike, Richard Lugar, and Bob Dole.

Huntsman would have ended up losing anyway. But in the process he could have created an enduring platform for himself as a man of integrity who fights for his principles, who puts beliefs ahead of electoral gain—a sort of Ron Paul of the Rockefeller Republican set. And that, surely, would have been a more favorable legacy—both for him and for other Republican pragmatists who believe the party, with its embrace of voodoo economics, retrogressive social values, and pseudo-science, is on a path to self-destruction.

As things turned out, Huntsman did very little of this. Rather than calling out the right (and Romney for pandering to it) he tried in vain to win over conservatives. When, predictably enough, that strategy didn't work, he got on his moral high horse and lectured his opponents about failing the American people.

That isn't engaging in practical politics: it is ducking the fight and stroking one's own ego. And it is also why, unlike many other commentators, I won't be lamenting Huntsman's early exit from the race.

Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty Images.

January 13, 2012

The Bain Bomb: A User's Guide

Now that Newt Gingrich's campaign has gone nuclear and posted online a critical documentary about Mitt Romney's career at Bain Capital, "When Mitt Romney Comes to Town," I thought it might be useful to provide a handy guide to the story—explaining where it came from and how you can find out more about it. It's not new, of course. Over the past decade, writing about Mitt and Bain has been something of a cottage industry. But now, like one of Bain Capital's successful investments, it has mushroomed into a much bigger business.

Where did the film come from?

Although the Gingrich campaign is promoting the video, and using slices of it on commercials, it didn't make it. The producer was Barry Bennett, a Republican political consultant who used to work with a Super PAC associated with Rick Perry. Bennett told the New York Times he got the idea to make the film after buying an "opposition research book" from the campaign of one of Romney's opponents in the 2008 Republican primaries. "Republicans need to know this story before we nominate this guy," he said. According to Bennett, Jason Killian Meath, an ad man and filmmaker who worked on Romney's 2008 campaign and George Bush's 2004 campaign, directed the documentary.

How can I see it?

Click on the still above for the full film, or, if you'd prefer not to watch all twenty-eight minutes, we've posted a clip of the highlights on The New Yorker's Political Scene page.

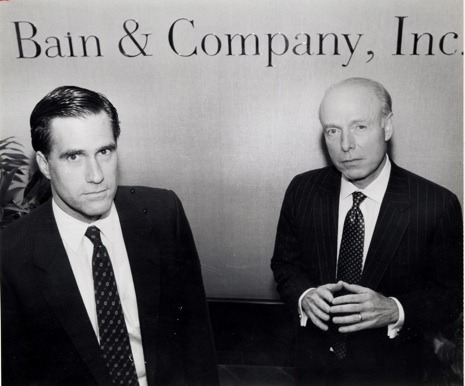

What is Bain Capital and what did Romney do there?

Bain Capital is a leveraged-buyout company, which Romney helped to found in 1984 and ran as C.E.O. until 1999. In 2007, when Romney was first running for President, the Boston Globe published a series of articles entitled "The Making of Mitt Romney." Part 3, "Reaping Profit in Study, Sweat," by Robert Gavin and Sacha Pfeiffer, covered Romney's career at Bain Capital in detail. It went through a number of deals in which the firm had made a lot of money while closing factories, eliminating jobs, using tax-sheltered offshore accounts, and, in some cases, driving the companies it had bought into bankruptcy. "Bain Capital is the model of how to leverage brain power to make money," Howard Anderson, a professor at M.I.T.'s Sloan School of Management, told the Globe. "They are first rate financial engineers. They will do everything they can to increase the value. The promise (to investors) is to make as much money as possible. You don't say we're going to make as much money as possible without going offshore and laying off people."

Since 2007, dozens of well-researched articles about Romney and Bain have been published, many of them focussing on particular deals or issues. A pretty recent one which covers the entire tale, and which is particularly strong on Bain Capital's internal culture, is "The Romney Economy," a cover story for New York magazine last fall by Benjamin Wallace-Wells. The author interviewed a number of Romney's former colleagues, describing how they emerged from the nineteen-seventies world of management consulting—Bain Capital was an offshoot of the consulting firm Bain & Co.—and how they viewed themselves as crusaders for economic efficiency. Wallace-Wells writes, "When I interviewed Romney's early colleagues about the business world that they surveyed during this period, they tended to adopt an attitude of high disdain. 'Sloppy,' one told me. 'Complacent,' said another. 'Lazy,' said a third, 'and out of tune with the change that was going on in the world.' "

What is the meaning of "leveraged buyout," and is it the same as "private equity"?

Yes, they are the same thing. Both refer to the practice of using wads of borrowed money to buy troubled or slow-growing public companies, taking them private, and then trying to turn them around and sell them on to another corporation at a higher price, or to investors in an initial public offering. Takeovers financed by debt have been around since the sixties. But the modern private-equity industry dates back to the early eighties, when investors like William Simon, a former under-secretary at the Treasury, and Henry Kravis, the co-founder of the L.B.O. firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (K.K.R.), made huge profits buying and selling companies using debt financing. Bain Capital was another early player, and it started out small. Initially, it had just just $37 million in capital.

The L.B.O./private-equity industry has always had an image problem. In the eighties, it was associated with junk bonds and Michael Milken, the disgraced Drexel Burnham investment banker who raised money for many L.B.O. players, including Bain Capital. ("The Predators' Ball," a 1989 book by my colleague Connie Bruck, is an excellent account of this period.) As time went on, more and more people entered the industry, and the deals got bigger and bigger—culminating in 1988 in K.K.R.'s $25 billion buyout of RJR Nabisco, the food and tobacco conglomerate.

In the recession of the early nineties, some of the companies that had been taken private in L.B.O.s went bankrupt because they couldn't meet their heavy debt payments. The industry was also tarnished by negative publicity surrounding Milken and the RJR Nabisco takeover, which Bryan Burrough and John Helyar wrote up in their 1990 best-seller "Barbarians at the Gate." Realizing that the industry badly needed rebranding, somebody came up with the idea of renaming it "private equity." The label stuck, and the industry gradually rebounded.

How much do we know about Bain Capital's record? Was it as successful as Romney says it was?

From the perspective of its partners and its outside investors, Bain Capital was phenomenally successful. The best source on its financial record under Mitt is a prospectus that Deutsche Bank Alex. Brown put together for potential investors in 2000. (The Los Angeles Times unearthed the prospectus and posted it on its Web site.) The prospectus listed sixty-eight companies that Bain Capital's private-equity funds invested in between 1984 and 1998. It said the funds made an annual return of eighty-eight per cent, which means they almost doubled their money every year. On "realized investments''—companies that Bain Capital had sold or taken public in an I.P.O.—the investment funds did even better. Over this fifteen-year period, according to the prospectus, the realized investments generated an astonishing annual return of a hundred and seventy-three per cent.

How did Bain Capital generate such high returns? What was the secret to its success?

In the private-equity industry, a key issue is picking the right companies to invest in. The ideal target is a sleepy firm with a low stock-market valuation, solid cash flow, and some underutilized assets. With their financial expertise and their background in the consulting world, Romney and his partners were very clever at spotting such targets. And once they had taken over a company, they went all out to extract value from it.

In the words of the Deutsche Bank prospectus, "Bain Capital's investment philosophy is characterized by its demonstrated belief that a combination of strong management, sound fundamental business analysis, focused strategy, and aggressive action substantially improves a business's profits and value." The "aggressive action" often involved shuttering under-performing divisions, laying off workers, and shifting production to cheaper locations in the United States or abroad.

For the most part, Romney and his colleagues at Bain Capital didn't do this themselves. After buying a company, they installed managers, gave them a substantial ownership stake in the form of shares or stock options, and urged them to get on with it. (Sometimes these were the same managers who had sold the firm to Bain.) In order to keep an eye on things, one or more partners of Bain usually sat on the company's board of directors. "You have the total alignment of incentives of ownership, board and management—everyone's incentives are aligned around building shareholder value," David Dominik, one of Romney's early colleagues, told Wallace-Wells. "It really is that simple."

How many of the firms that Bain Capital invested in went bankrupt?

According to a recent story in the Wall Street Journal, more than one in five of the companies that Bain Capital invested in between 1984 and 1999 went bankrupt or shut down within eight years of Romney and his colleagues getting involved. The Journal reporter Mark Maremont tracked the fate of seventy-seven of the companies listed in the Deutsche Bank prospectus. Some of them had been resold to other companies by the time they went into bankruptcy. "Bain backers argue it is unfair to tag the firm with any bankruptcy that occurred several years after it took a company public or sold it," Maremont noted. "Others have said the firm and its former leader could still bear some responsibility for failing to leave the company in strong shape."

If so many of the firms that Bain Capital financed ending up closing down or going bankrupt, how was the firm able to make so money?

In several ways. Most of the firms that Bain invested in didn't go bust. Some of them prospered mightily. In the private-equity game, a few big successes can disguise a lot mediocre investments, and even some duds. According to the Journal article, more than seventy per cent of Bain Capital's investment gains under Romney came from just ten of its investments, which turned out very well. The firm made a profit of $373 million on its investment in an Italian yellow-pages company, $302 million on its investment in Wesley Jessen VisionCare, and $186 million on its investment in a medical-diagnostics company called Dade.

Even if the companies they invest in ultimately run into trouble, buyout firms like Bain Capital can make a lot of money in the interim. They can sell off non-core assets, extract generous management fees, and pay themselves special dividends financed by debt issues. Romney and Bain Capital did all of these things. "The private equity business is like sex," Howard Anderson, the M.I.T. professor, told the Boston Globe in 2007. "When it's good, it's really good. And when it's bad, it's still pretty good."

Can you give me an example in which Bain Capital made a lot of money from a company that failed?

During the early nineties, Bain Capital bought an old steel mill in Kansas City from Armco Steel Corp., and merged it with other plants it had acquired in South Carolina and elsewhere under the name GS Industries. It was Bain Capital's tenth-largest investment under Romney.

According to a recent account by the Reuters reporters Andy Sullivan and Greg Roumeliotis, within two years of investing eight million dollars to create GS Industries and take a majority interest, Bain Capital had paid itself a special dividend of $36.1 million, financed by a big issue of debt. (Some of this money was subsequently reinvested in the company.) G.S.I. subsequently struggled against domestic and foreign competitors. In 1999 it sought a federal loan guarantee, and in 2001 it entered bankruptcy protection. More than seven hundred workers lost their jobs, health insurance, and some of their retirement benefits. A federal agency had to put up $44 million to bail out the company's pension plan. Even while G.S.I. was fighting for survival, Bain continued to extract management fees from it—about $900,000 a year, according to a recent Los Angeles Times story. "Bain partners think the profits they made are a sign of brilliance," an official of the steel workers' union who negotiated with G.S.I. told the paper. "It's not brilliance. It's lurking around the corner and mugging somebody."

The Reuters story about G.S.I. came up in one of the New Hampshire debates, when Gingrich mistakenly attributed it to the Times. He said, "If you look at the New York Times article, and I think it was on Thursday, you would certainly have to say that Bain, at times, engaged in behavior where they looted a company, leaving behind 1,700 unemployed people."

A spokesman for Bain Capital told Reuters, "Over $100 million and many thousands of hours were invested in GSI to upgrade its facilities and make the company more competitive during a 7-year period when the industry came under enormous pressure and 44 U.S. steel companies went into bankruptcy. In the same period, we worked to turn around GSI, we helped launch and grow an innovative business called Steel Dynamics that is today a $6 billion global leader . Our focus remains on building great companies and improving their operations."

What about all those jobs Romney says he created? Is he right when he says the firms Bain Capital invested in have added about 100,000 jobs to the economy?

That's unclear. Some companies Bain invested in under Romney did subsequently create thousands of jobs: the Indiana-based steel company Steel Dynamics, the retirement-home operator Epoch Senior Living, and Domino's Pizza are three examples he cites. But other companies associated with Bain Capital, such as the retail chain KB Toys, the media company Clear Channel Communications, and DDi Corp, a maker of circuit boards, eliminated thousands of positions.

Romney says the 100,000 figure is a net one, meaning it is the number of jobs created minus the number of jobs eliminated. But there are two potential problems with it. The first is that the figure doesn't apply only to the period when Romney was running Bain, but to the firm's entire history to date: 1984 to 2012. Should Romney be taking credit for jobs created after he left Bain? That's what he's doing. His campaign hasn't said how many jobs Bain Capital created or eliminated during the fifteen years when he was running the firm.

The other issue with the 100,000 number is that it appears to include all the jobs created by Staples, the office-products retailer, which was Bain Capital's biggest success story under Romney. Since opening its first store in Brighton, Massachusetts, in 1986, the retailer has expanded worldwide. At the end of 2010, it employed 90,000 people, most of whom are sales associates.

Why is Staples special?

Romney certainly deserves credit for investing in Staples. The 2007 Boston Globe story and other accounts have made clear that he believed in the concept of an office superstore when many doubted it, agreeing to back the entrepreneur who founded Staples, Thomas Sternberg. But how many of the Staples jobs should be counted in the overall calculation? For one thing, many of them are abroad. For another, Staples wasn't a typical Bain Capital deal, in which the firm took over a well-established company and tried to gussy it up for resale. It was a startup. Bain made a "venture capital" investment—of just $650,000 initially.

As Bain Capital grew, its venture-capital investments, which Romney now talks about a lot, became a smaller and smaller part of its business. And this wasn't an accident: it was a deliberate strategy shift on Romney's part. "Despite the success of Staples, the venture capital world had too many unknowns for Romney's taste," the 2007 Boston Globe story noted. "So he steered the firm to focus squarely on leveraged buyouts. 'I didn't want to invest in start-ups where the success of the enterprise depended upon something that was out of our control,' Romney recalled recently, 'such as, could Dr. X. make the technology work?' "

For a long time, Bain Capital was less well known than other big buyout firms, such as K.K.R., Blackstone, and the Carlyle Group. Why was that?

Based in Boston, Bain Capital deliberately stayed out of the Wall Street limelight. With Romney in charge, it eschewed big, splashy deals like the RJR Nabisco takeover. A cautious investor, Romney preferred to buy smaller, more obscure firms that it could operate and resell away from the media glare. "Mitt was always worried that things weren't going to work out—he never took big risks," one of his former colleagues told Wallace-Wells."I think Mitt had a tremendous amount of insecurity, and fear of failure."

As the years went on, Romney did greenlight some bigger deals. They included the 1998 buyout of Domino's Pizza, in which Bain Capital invested $189 million; the 1996 buyout of Experian, a financial-information company in which it invested $88 million; and the 1997 buyout of Sealy Mattress, in which it invested $40 million.

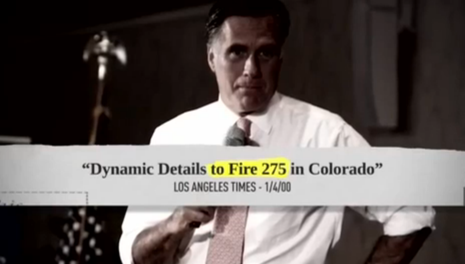

When did Bain's business practices first turn into a political issue for Romney?

In October, 1994, when Romney was running for the U.S. Senate against Ted Kennedy, a group of workers who had lost their jobs at a plant in Marion, Indiana, operated by American Pad & Paper (Ampad), a manufacturing company that Bain Capital had bought out two years earlier, drove to Boston and started heckling him at political events. The workers told anybody who would listen how, with Bain Capital's backing, Ampad had fired two hundred and fifty union workers, offering to hire some of them back at much lower wages and with less generous health-care coverage.

The uproar over the Ampad workers helped Kennedy to defeat Mitt handily. That didn't stop Ampad from closing down the Indiana plant a few months later, eliminating practically all the jobs there. And in the end, Bain Capital's involvement with Ampad turned out to very remunerative. In 1996, the company went public in an I.P.O., enabling Bain to cash out some of its investment. But Ampad remained heavily indebted, and in 2000 it filed for bankruptcy. By then, according to the Deutsche Bank prospectus, Romney and Bain Capital had made $102 million on an initial investment of just $5 million.

For Romney, the Ampad story has never gone away. The 2007 Boston Globe series mentioned above details the Ampad saga, and examines it in this sidebar, and a 2008 Globe story looks at Romney's role, and how it played out politically. In another important and early look at Bain Capital, which was published in December, 2007, the Los Angeles Times reporter Bob Drogin interviewed one of Romney's colleagues who served on Ampad's board of directors, Marc B. Wolpow. "They're whitewashing his career now," Wolpow said. "We had a scheme where the rich got richer. I did it, and I feel good about it. But I'm not planning to run for office." At the time Ampad shut down its plant in Marion, Romney was back running Bain Capital. "He was in charge," Wolpow told Drogin. "He could have ordered me to settle with the union. He didn't order me to do that. He let me take decisions that would maximize the value of the investment. That was the right decision as CEO of Bain Capital. But let's not pretend it was something else."

Not surprisingly, the Ampad story also features prominently in the new documentary.

How much tax has Romney paid on all the money he made at Bain Capital?

That is another question that has yet to be answered. Romney hasn't released any of his recent tax returns. A front-page story in the Times last month, by Nicholas Confessore, Christopher Drew, and Julie Creswell, revealed that, although he left Bain Capital in 1999, his retirement agreement entitled him to share in the profits that the firm made on all of its deals through 2009. And the story noted, "Much of his income from this arrangement has probably qualified for a lower tax rate than ordinary income under a tax provision favorable to hedge fund and private equity managers, which has become a point of contention in the battle over economic inequality."

That "probably" is probably superfluous. Managers of private-equity funds, even retired ones like Romney, routinely class much of the income they receive as "carried interest," which is taxed at just fifteen per cent—compared to a top rate of income tax of thirty-five per cent. Billionaire private-equity moguls like Kravis and multi-multi-millionaire private-equity moguls like Romney have presumably been exploiting this loophole for years. If and when Romney publishes his tax returns, outside experts will be able to figure out how much he has saved in recent years, and whether, as some suspect, the effective federal tax rate he paid was lower than the rate that many middle-income workers pay.

With the South Carolina primary coming up, is there a local angle to the Bain Capital story?

Yes, there is. Last month, the Associated Press published a story entitled "As Romney's Firm Profited in S.C., Jobs Disappeared." By Jack Gillum, it focussed on a manufacturing plant in Gaffney, South Carolina, which a company controlled by Bain closed down in 1992. What happened in Gaffney shows "how Bain, then headed by Romney, wrung profits out of the company by slashing costs and trimming its work force," Gillum wrote.

The owner of the plant was Holson Burnes Group, a maker of picture frames and photo albums, which was one of Bain Capital's first acquisitions. In the late eighties, according to the A.P. story, South Carolina officials lured Holson Burnes to Gaffney with a package including $5 million in industrial bonds. The factory opened in 1988 and soon employed more than a hundred people. But in 1992, Holson Burnes closed it down, laying off about a hundred and fifty workers. Some of these jobs were moved to New Hampshire, but eventually Holson Burnes shifted most of its production overseas.

For Bain Capital and Romney, the investment in Holson Burnes proved a profitable, if relatively minor, venture. According to the Deutsche Bank prospectus, the buyout firm invested about $10 million in the company and realized about $23 million, making an annual return of about twenty per cent.

Top photograph, of Romney and William Bain, Jr., by Justine Schiavo/The Boston Globe via Getty Images. All other images are stills from "When Romney Came to Town."

January 11, 2012

Super Mitt: Ten Things Romney Got Right

As this is Mitt's moment, and some readers have been complaining that I haven't been giving him his due, I thought I'd draw attention to some of his achievements, starting with his great victory in New Hampshire. Here's a list of ten. Unfortunately, for political reasons, he can't publicly take credit for several of them—see #s 4, 7, and 9—but that shouldn't detract from their importance.

1) In what is almost an adjunct of his own state (much of N.H. is part of the Boston media market) he defeated by sixteen points a Texan goblin who wants to legalize marijuana, abolish the Federal Reserve system, restore the gold standard, and get rid of the I.R.S. This followed a (disputed) eight-vote victory in Iowa over a candidate who has questioned the legality of gay sex and said contraception is "not O.K."

2) Delivering a well-calibrated victory speech on Tuesday night, he managed to accuse his rivals of treachery for criticizing his business record at Bain Capital, and without mentioning them or the company by name. "President Obama wants to put free enterprise on trial," he said. "In the last few days, we have seen some desperate Republicans join forces with him. This is such a mistake for our Party and for our nation."

3) He looks "Presidential." That doesn't mean he looks like a real President: during the past twenty years, we've had a potato head, a jug ears, and a manorexic in the Oval Office. But with his erect gait, broad shoulders, and Mad Men fashion sense, Mitt resembles Hollywood's idea of a president. After all this time, it will be good to have somebody in charge who, like Ronald Reagan, recognizes the value of hair dye.

4) After forty years of vain efforts by progressive politicians and public-policy experts, he successfully introduced to the United States the principle of universal health-care coverage. In June, 2010, according to the Urban Institute, more than ninety-eight per cent of Massachusetts's residents had health coverage. In the country at large, the figure is about eighty-three per cent.

5) Unlike some of his rivals, he hasn't resorted to calling Barack Obama a socialist, a Kenyan anti-colonialist, or an un-American agitator. Instead, he says Obama is a closet—wait for it—European! This also from his victory speech in N.H.: Obama "wants to turn America into a European-style entitlement society. We want to ensure that we remain a free and prosperous land of opportunity. This President takes his inspiration from the capitals of Europe; we look to the cities and small towns of America."

6) In an encouraging sign that he knows how to deal with mischief-makers like Iran and North Korea, he has already tamed one potentially errant foe: his hair. Following an unauthorized incursion onto his lower brow during a debate in November, it has remained obediently confined to its own territory.

7) Despite his rhetoric about China stealing American jobs, he recognizes the economic reality: developing countries provide high-quality goods at cheap prices. During last Saturday's debate, he said, "Contraception—it's working just fine. Leave it alone." These days, most condoms are manufactured in China and India.

8) He squashed Newt. By deploying some of its cash pile on negative ads in Iowa, his Super PAC saved us from a possible summer and fall full of lectures on President Obama's "secular socialist machine," why the Palestinians are "an invented people," and why poor kids should be forced to work part-time as assistants to the janitors in their schools.

9) As governor of Massachusetts from 2003 to 2007, he was a non-ideological problem solver, working with people from a variety of political backgrounds to rein in state spending, convert a budget deficit to a surplus, and complete Boston's notorious "Big Dig." According to Nicholas Kristof, even Bill Clinton has said Mitt did "a very good job" in Massachusetts.

10) He's rehabilitated flip-flopping. Who hasn't changed their mind on at least one important issue? To be sure, Mitt's done it on more than most—on abortion, gun control, taxes, the stimulus, Ronald Reagan, etc.—but, hey, it's the principle that counts: the principle that consistency on anything and everything isn't necessarily a cardinal virtue.

(Further suggestions will be gratefully received.)

Photograph by Fang Zhe/Xinhua News Agency.

January 10, 2012

MITT'S BIG WIN ISN'T THE BIGGEST NEWS STORY OF THE WEEK

With the results of the New Hampshire primary coming in almost exactly as expected last night, the 2012 Presidential race has now seen four significant developments within a few days. In order of importance, this is how I would rank them—number one being the most significant and number four the least:

4) Mitt Romney's big victory: As the results came in, Mitt's supporters were understandably keen to remind us that this is the first time a non-incumbent Republican candidate has been victorious in both Iowa and New Hampshire. According to exit polls, he did well among all the major voting groups in the Republican party, winning over forty-two percent of conservatives—more than twice the share of his closest rival, Ron Paul—and thirty seven per cent of moderates and liberals. He finished ahead among high school graduates, college graduates, and post-graduates. He was the first choice of Protestants and Catholics. He even came out in front among tea party supporters. And a hefty sixty-six per cent of voters said he would be the most likely candidate to beat Barack Obama.

This was all very encouraging for Romney. But none of it was surprising. With about ninety-five per cent of the ballots counted, Romney's share of the vote was close to forty per cent—very close to what the Real Clear Politics poll-of-polls had been predicting. The political professionals, commentators, and betting markets had already discounted the result. Even before the polls closed, in the media salons and green rooms it was almost universally accepted that Romney was practically home free, and that only something very unexpected could trip him up.

3) Paul's second place finish: From a strategic perspective, this was even more important to Romney than the generous scale of his own victory. As long as Paul is the leading alternative to Romney, he has no electable challenger—and by electable I mean electable to the Republican Party, not the country at large. If any of the other candidates had knocked Paul into third place, they could have gone into South Carolina and Florida credibly claiming to represent the anti-Romney forces within the party, which remain numerous and vocal. But Paul's twenty-three per cent of the vote left the situation unchanged: this race is Mitt and the five dwarves.

With about ten per cent and nine per cent of the vote respectively,Gingrich and Santorum both had bad nights. The momentum Santorum gained in Iowa is now in question, as is Gingrich's decision to play the attack dog. As for Huntsman, given where he was a week ago, a third-place finish with seventeen per cent of the vote was creditable, but no more than that. His claim last night that "a third place finish is a ticket to ride" will only prove true if he can persuade his pop, the chemical tycoon Jon Huntsman Sr., to pour millions of dollars into his empty campaign chest. Even then, it would be far from clear that he has a future, partly because his candidacy remains undefined. Is he the moderate alternative to Romney or the conservative alternative?

2) The Bain Bomb explodes: All along, the Obama campaign has been planning to depict Romney, whom it has long expected to be the nominee, as a greedy, out-of-touch billionaire who made his fortune buying companies with borrowed money, looting them, and firing the workers. The problem the White House faced was getting people to believe this story. Coming from a political opponent, there was obviously a credibility problem attached to it.

No longer. Once Gingrich started criticizing Romney's record at Bain Capital, the looting narrative turned into one that had bipartisan endorsement. There were reports last night that some of Gingrich's friends in the Republican Party were pressing him to tone down his criticisms of Romney's business career and persuade his Super PAC not to run negative ads based upon it. But with Sheldon Adelson's millions behind him, and the South Carolina primary just ten days away, the Georgian has little incentive to hold his fire.

And it isn't just Newt. On Fox News last night, Rick Perry, who didn't campaign in New Hampshire, framed the Bain Capital issue as "venture capitalism versus vulture capitalism." He talked about Bain's business practices and referred to "places where they came in and destroyed peoples lives," adding that Romney "is going to have to face that when he comes to South Carolina."

1) The fall in the unemployment rate: Romney's platform for November is admirably clear. With his business expertise, he is the man to create jobs and get America moving again. In his victory speech last night, he pledged that he would spend every day in the White House "worrying about your job, not about saving my own job." On television later, Tim Pawlenty, the former governor of Minnesota who dropped out of the presidential race last summer, and who is now acting as surrogate for Romney, said, "there is one candidate in this race who has started a business, grown a business, and created jobs."

As long as the economy was in a recession, or a near-recession, Romney's candidacy had an obvious plausibility to it. Now, that things are improving and the jobless rate has fallen from 9.4 per cent to 8.5 per cent, the case for Mitt isn't nearly so obvious. Following Friday's jobs report, he has already been forced to pivot away from the argument that there won't be any real recovery until there is a change at the White House. His modified position is that, yes, there is an economic rebound of sorts, but one that hasn't got anything to do with President Obama—indeed his policies only retarded it.

Assuming that Romney goes on to wrap up the nomination, it is still perfectly possible that he will be able to sell this story to the American public and win the election. So far, at least, the revival in employment hasn't translated into a sustained uptick in President Obama's approval rating. But Mitt would find it much easier to make the sale if the unemployment rate was stable or rising come the spring and summer. Which is why the upturn in the labor market remains, by far, the biggest political story of the last week.

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images.

In Defense of Political Journalists

If there's one thing most people can agree on these days it's that political reporting has gone to the dogs. Even some of my colleagues subscribe to this view. In a Daily Comment last week, George Packer had a rip at the reporters covering the Republican primaries, lamenting that they no longer cover real issues but merely treat politics as light entertainment. George was particularly exercised about the campaign posse's failure to dwell on Rick Santorum's comment in Iowa that President Obama is engaging in "absolutely un-American activities." George wrote, "Once demagogy and falsehoods become routine, there isn't much for the political journalist to do except handicap the race and report on the candidate's mood."

This sounds kind of serious. Maybe those tweet-happy, trivia-obsessed McMuffins really are letting down the profession and the country, turning Presidential politics into a game show. And since I'm sitting here waiting to find out how the horse race in New Hampshire turns out, rather than doing some research into the historical demonization of African-American political leaders, or whether Mitt Romney's get-tough approach to China is credible from a game-theoretical perspective, maybe I'm guilty of the same thing.

But wait a minute. Over breakfast this morning, I read the front section of the Times, which contains almost four full pages of political coverage, much of it tied to today's New Hampshire primary. There were reports on how Romney has spent years cultivating local political leaders, on how the campaigns are already blanketing the airwaves in South Carolina, and a particularly interesting story on the relationship between Newt Gingrich and Sheldon Adelson, the Las Vegas casino billionaire and fervent Zionist, who has just donated five million dollars to a Super PAC tied to the Georgian. Sitting down at my desk, I picked up an investigative report from yesterday's Wall Street Journal that I had printed out. It examined the history of seventy-seven businesses that Bain Capital, Mitt Romney's old firm, invested in between 1984 and 1999, and revealed that more than one in five of them (twenty-two per cent) had filed for bankruptcy.

To my eyes, anyway, these were all examples of serious political journalism: well reported, clearly edited, and soberly presented. And today is nothing special. On any other morning, I could pick out at least three or four similarly informative articles, some of which would probably come from less traditional news sources. Only yesterday, I was reading another piece about Romney's time at Bain, which I learned about on Twitter. It came from BuzzFeed, a fast-growing news site that recently hired Ben Smith, a former columnist at Politico and the Daily News, as its editor-in-chief.

In fact, having recently returned to writing about politics after a long absence, I am struck daily by the range and depth of the information on offer. When I first started reporting from Washington, in 1988, I used to stand by the A.P. and Reuters ticker-tape machines waiting for them to spew out the latest news from the White House or the State Department. These days, sites like Politico, the Huffington Post, and nytimes.com provide real-time coverage of virtually anything that is happening. and the material that forms the basis of their reports is often available directly from the Web sites of government departments and other organizations. If I want to find out which individuals or corporations have contributed most to Romney's campaign, I can go to OpenSecrets.org, a Web site run by the Center for Responsive Politics. Indeed, the Center itself puts out some good news stories. Last week, it reported that the Tea Party Republicans in Congress are, on average, wealthier than other Republican members of Congress, which is hardly what you might expect.

I would offer the perhaps heretical suggestion that political journalism, far from having gone into a terminal decline, is in better shape now than it was back in the nineteen-sixties and seventies, which some hold up as a golden age. Back then, the American media world was a cozy oligopoly, and, like all oligopolies, it limited its output. On television, the three networks provided half an hour of evening news, much of it unrelated to politics, and, from 1980 onwards, one decent late-night news show: ABC Nightline. In print, the big metropolitan papers and the three newsweeklies dominated things, largely to the exclusion of other players.

To be sure, the quasi-monopolies produced some first-rate political journalism, but they also produced a lot of junk: glorified stenography, hagiographies disguised as inside accounts, and "authoritative" books as thick as doorsteps that no living soul could read from start to finish. Much of the truly memorable political writing came from people outside the media-industry power structure, such as Norman Mailer and Hunter S. Thompson. (Even Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, it shouldn't be forgotten, weren't members of the White House press corps when they started writing about Watergate. They were on the Washington Post's Metro desk.)

To describe run-of-the-mill political coverage thirty years ago as being about "what is true, what is important," which is what George says it should be about, would be to adopt a rosy-tinted view of history. When Ronald Reagan came to power, the so-called "liberal press" proved so supine that the writer Mark Hertsgaard titled his account of the media and the White House "On Bended Knee." It would also be a big stretch to say that political reporters back then were less interested in the horse race, and kept their eyes fixed on the higher thing. (If you doubt me on this one, go and pick out your dog-eared copy of "Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail" or "The Boys on the Bus," both of which are devoted to the 1972 campaign.)