John Cassidy's Blog, page 118

February 4, 2011

Lies, Damn Lies, and (Job) Statistics

Even as a determined insta-pundit, there come times when you have to throw up your hands and say, "Who knows?"

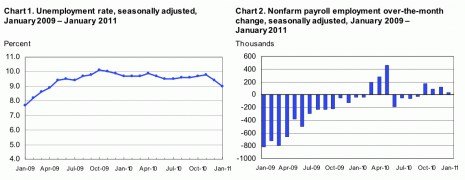

Take the January jobs report, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics released this morning. It showed a significant fall in the unemployment rate (from 9.4 per cent to 9.0 per cent) AND a significant fall in the pace of hiring (payrolls rose by just 36,000 last month, compared to 121,000 in December). It doesn't take a great grasp of economics to figure out that when firms cut down on hiring the unemployment rate should increase. But last month, the opposite happened. Or did it?

Fortunately, I wasn't alone in my befuddlement.

"Given the confounding nature of this report, we will have to wait at least another month to see if the labor market is rebounding strongly," said Heidi Shierholz, of the Economic Policy Institute.

"It's all a mystery," said Robert Brusca, chief economist at F.A.O. Economics.

As I've pointed out before, the employment report is perhaps the most confusing of all the government's economic reports. This is mainly because it consists of two different surveys—one of households and one of firms. The unemployment rate is derived from the household survey, which covers about sixty thousand households. The hiring figures come from the establishment survey, which samples about a hundred and forty thousand businesses.

With samples this large, you might think the surveys would agree, but sometimes they don't, and this was one of those occasions. According to the household survey, the number of unemployed fell six-hundred thousand last month—a figure that is virtually impossible to reconcile with the hiring figure of 36,000 from the establishment survey.

So what is going on?

The awful weather in January, by forcing many firms to close temporarily, appears to have played havoc with the payroll figures. The government statisticians try to account for seasonal factors, but January was unseasonably cold and snowy. According to the household survey, some 886,000 people were unable to work because of the inclement weather, which is more than twice the long-run average of 417,000.

Some Wall Street analysts reckon the cold reduced the January hiring figure by upwards of 80,000. If they are right, the economy really created at least 120,000 jobs last month. That isn't great, but it's about the same as the December figure. In which case, the overall state of the labor market is roughly the same as it has been for the past year or so. Companies are finally hiring, but the overall rate of job growth doesn't match the pace of previous recoveries, partly because state and local governments are jettisoning workers at a virtually unprecedented rate. I (and others) had been expecting a more vigorous pickup, but as of now the optimistic case remains unproven.

As always, it is unwise to make too much of one month's figures. Perhaps the most interesting part of today's report was the revised figures that the government provided for the period going back to January, 2006. These revisions incorporate information that wasn't available when the original figures were put together, such as recent tax filings, and they provide a grim picture of the Great Recession and its aftermath. All told, according to the official statisticians, some 8.7 million jobs were lost during the recession. And of those, just 950,000—about one in nine—has been recovered.

Of course, employment is what economists term a lagging indicator. It often doesn't recover until other economic aggregates, such as consumer spending and industrial production, have been growing for quite a while. By now, though, it should be growing much faster—a point that Fed chairman Ben Bernanke noted yesterday. "Until we see a sustained period of stronger job creation," Bernanke said, "we cannot consider the recovery to be truly established."

I still expect private-sector employment to pick up sharply one of these months. But I concede this hopeful line is getting tired. Now, let's see what February brings…

January 27, 2011

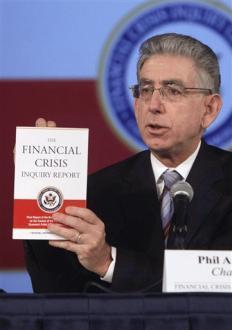

Two Cheers for the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission

My quick (and self-serving) takeaway from today's report from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission: That sounds familiar! Much of the report jibes with the analysis in my book, "How Markets Fail: The Logic of Economic Calamities." The commissioners present the subprime blow-up as a product of deregulation, misaligned incentives, and misplaced faith in dodgy risk models; they criticize policymakers for being unprepared to deal with the crisis; and they say the decision to let Lehman Brothers fail was a big mistake.

Of course, my language was a bit more colorful than theirs, as evidenced by these examples:

HMF: "When historians come to write about 'Greenspan Bubbles,' they will do with good cause: more than any other individual, the former Fed chairman was responsible for letting the hogs run wild."

FCIC: "More than 30 years of deregulation and reliance on self-regulation by financial institutions, championed by former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and others…had stripped away key safeguards, which could have helped avoid catastrophe."

HMF: "At the risk of outraging some readers, I downplay character issues. Greed is ever present: it is what economists call a 'primitive" of the capitalist model. Stupidity is equally ubiquitous, but I don't think it played a big role here."

FCIC: "(T)o pin this crisis on mortal flaws like greed and hubris would be simplistic. It was the failure to account for human weakness that is relevant to this crisis."

HMF: "(A)fter all the mergers that the government orchestrated during the crisis, six huge firms…now dominate the financial industry, wielding enormous power and influence…The ratings agencies remain unreformed, as do the myopic compensation packages for Wall Street traders and CEOs that helped bring on the crisis."

FCIC: "Our financial system is, in many respects, still unchanged from what existed on the eve of the crisis. Indeed, in the wake of the crisis, the U.S. financial sector is now more concentrated than ever in the hands of a few large, systemically significant institutions."

Given these likenesses, I obviously agree with the main thrust of the report, which is that the crisis could have been avoided: it wasn't a once-in-a century natural disaster, as some people on Wall Street, and even Ben Bernanke, have intimated. Moreover, the Commissioners did a good job of dispelling some conservative myths, such as the suggestion that the real culprit was the Community Reinvestment Act, which encouraged banks to make more loans in poor areas, or Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government-sponsored mortgage giants.

"The CRA was not a significant factor in subprime lending or the crisis," the report says. "Many subprime lenders were not subject to the CRA. Research indicates only 6% of high-cost loans—a proxy for subprime loans—had any connection to the law." As for Fannie and Freddie, they "participated in the expansion of subprime and other risky mortgages, but they followed rather than led Wall Street and other lenders in the rush for fool's gold."

It is good to get these things down in an official report. Still, I do differ from the Commissioners in a couple of areas: its treatment of monetary policy and economics.

Despite criticizing Greenspan, the report gives him something of a pass on the charge that his low-interest rate policy helped give rise to the blow-up, putting more emphasis on the Fed's failure to regulate the mortgage market and oversee Wall Street. It states flatly, "excess liquidity did not need to cause a crisis." I think this underestimates the role that credit conditions (the cost and availability of borrowing facilities), which are largely determined by the Fed, play in today's world. As I wrote in my book: "In a modern economy with a large financial sector, the combination of cheap money and lax oversight, if maintained for years on end, is sure to lead to trouble."

My other quibble with the report concerns its failure to place any responsibility on free market economics and its exponents. Once you have assigned blame to the policymakers, the mortgage lenders, the Wall Street C.E.O.s, the traders, the credit raters, and the risk modelers, the next step, surely, is to ask what, if anything, all these people shared in common. My answer—and the reason this blog is called "Rational Irrationality"—is that almost of them were responding rationally to market signals, and they were doing so in the belief that as long as they did this nothing much could go wrong.

Why did they think this? Some of them, to be sure, were victims of disaster myopia, but there was also a common assumption that free markets—in this case, financial markets—serve to convert individual acts of self-interest into benign social outcomes. In short, markets work well.

What we have learned, or relearned, at great cost is that sometimes markets don't work well. They fail horribly. And that, I suggest, would have worth pointing out (again).

Photograph: AP/Jacquelyn Martin

January 26, 2011

Why Is Obama Smiling?

All State of the Union addresses are political statements: this one was more carefully crafted than most. In wrapping himself in the flag and mouthing platitudes such as "This is our generation's Sputnik moment" and "This is a country where anything is possible," President Obama wasn't merely channelling Ronald Reagan (although at one point I thought he was going to start talking about "a shining city on a hill"). He was setting out the terms for a bitter fiscal debate, which is going to dominate the next two years.

Having spent much of last fall arguing (correctly) that during a recession wasn't the right time to try and reduce the deficit, the President has shifted ground and agreed to fight on the Republicans' terms: "Now that the worst of the recession is over," he said, "we have to confront the fact that the government spends more than it takes in." In repeating his pledge to freeze discretionary domestic spending for four years, while at the same time calling for more public investments in education, infrastructure, and alternative energy, he was trying to strike a tricky balance between fiscal orthodoxy and techno-optimism.

I thought his best line was comparing Facebook and Google to Thomas Edison and the Wright Brothers. Still, Brit Hume of Fox News had a point when he asked of Obama's public investment proposals, "How much borrowed money, Sir, are you willing to spend on these items?" We won't know the answer until next month, when the Administration delivers its budget for the fiscal year of 2012, which begins in October.

It is tempting to think of deficit reduction as an endeavor that naturally favors Republicans, but for several reasons that would be a mistake. We are entering a fascinating period in which Republicans have the political energy and ideological impetus, but President Obama has the tactical advantage. As the fiscal battle gets going in earnest, three things will play in his favor.

The first is structural. In a balkanized political system such as ours, which was expressly designed to prevent strong government, being President is a bit like quarterbacking a January playoff game in Chicago or Green Bay: defense is much easier than offense. Having spent the first half of his Presidency getting roughed up by Rex Ryan-style blitzes, the President is now moving to the sideline, waving his defensive line into position, and inviting John Boehner and his teammates to try and score some points against them.

As Newt Gingrich discovered in the mid-nineties, making policy from the House of Representatives is mightily difficult. Rudyard Kipling said harlots have power without responsibility. Congressional leaders such as Gingrich, and now Boehner, are in the opposite position: they have responsibility without power. If they don't meet the expectations of their supporters, a backlash is inevitable. If they do play to their base, they risk alienating the country at large.

The Republicans' dilemma was clearly visible last night. Representative Paul Ryan and Tea Party darling Michele Bachmann both made clear that they are determined to slash federal spending, or, at least, to be seen trying to do so. However, aside from calling for a repeal of Obama's health-care reform, neither made any specific proposals on which programs to cut. As the President pointed out, discretionary domestic outlays make up just twelve per cent of the budget. Without curbing entitlements and the defense budget, it is virtually impossible to bring down spending.

As the months progress, the White House will force the Republicans to get more specific about what they mean to do with Social Security, Medicare, and other high-cost programs. In Gene Sperling at the National Economic Council and Jack Lew at the Office of Management and Budget, the Obama Administration has two wily veterans of the fiscal wars. Both were members of the Clinton Administration team that negotiated the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. The Republicans, by contrast, look like callow rookies. Ryan, for example, is already on the record as proposing to turn Medicare into a privatized voucher program for anybody under fifty-five. (Good luck selling that one to the A.A.R.P.) And whatever the Republican leaders do, they will have the Tea Party ultras nipping at their heels.

Last but not least, President Obama may finally have the economy on his side. In recent weeks, many independent forecasters have been raising their estimates of G.D.P. growth from two to three per cent to three to four per cent. That might not sound like a big change, but if growth of close to four per cent does materialize it will start to have a significant impact on unemployment and the deficit.

Contrary to Republican claims, a big reason that the deficit exploded was a collapse in tax revenues rather than a spurt of stimulus spending. Between 2007 and 2010, federal revenues went from about eighteen per cent of G.D.P. to less than fifteen per cent—the first time they had fallen to such a low level since the nineteen-sixties. If growth picks up, so will tax revenues, and the deficit will start to come down of its own accord, relieving the political pressure to slash everything in sight. (Yes, the U.S. still has a worrying long-term structural deficit, but that has virtually everything to do with Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security, and virtually nothing to do with the stimulus program.)

No wonder the President seems so chipper. A couple of months ago, when he gave his speech about the "shellacking" of the midterms, he was gray and dejected. Last night, he looked like a man who has been sentenced to two years in jail, only to find he can serve his time at the Four Seasons Maui.

According to at least one objective source, the President's sunny demeanor is justified. This morning, Paddy Powers, the Irish bookmaker, made him the 4/5 favorite to win the 2012 election. (At these odds, you have to bet $50 to win $40.) Mitt Romney is second favorite at 8/1. Sarah Palin is 12/1. Mike Bloomberg is 25/1.

Photograph: Pablo Martinez Monsivais-Pool/Getty Images

January 25, 2011

Letter (not) from Davos

It's Davos week again, and we can expect the usual deluge of meaningless stories from journalists desperately trying to justify their presence at the annual Alpine shindig known as the World Economic Forum. If I were there, I'd be doing the same thing, but my invitation got lost in the mail. This year, sadly, I won't get the chance to discuss over breakfast with Bono how to alleviate African poverty, stop in for a nightcap with Tim Geithner, who is leading the American delegation, or cavort on the dance floor at the Google party with the girlfriend of a minor Russian oligarch.

The event is only just starting, but already the Huffington Post has set up a special Davos page with "Live Updates, Tweets, and More" and published a column from Arianna saying she is en route; the Financial Times has published a separate Davos supplement; and the BBC, which annually dispatches a small army of reporters, cameramen, and techies to the Eastern Alps at the U.K. taxpayers' expense, has broadcast a thrilling report about changes in the conference center's layout.

Amidst the dross, one story stands out: Andrew Ross Sorkin's column in Dealbook on what business executives pay to attend Davos. Four years ago, on my sole trip to the conference—I was working on a Profile of Paul Wolfowitz, who was then the head of the World Bank—I quickly grasped what was in it for the journalists: stunning scenery, free booze, and the chance to bypass the usual P.R. machinery and collar senior sources when they are drunk and chatty. But what about the twenty-five hundred or so business executives from companies such as PepsiCo, Bank of America, and Intel who make up the bulk of the crowd? Why do they show up?

As Ross Sorkin reveals, attendance certainly isn't cheap. A single membership of the World Economic Forum and a ticket to the conference costs $71,000. If you want to be included in the "private" discussion sessions that litter the agenda—which self-respecting C.E.O. wouldn't?—the price rises to $156,000. Bring your spouse or partner and the tab is $301,000. Add your secretary, your chief of staff, and your second cousin's husband who got a Ph.D. from Stanford in development economics and who might be able to feed you a few lines about how Botswana has largely avoided falling victim to the "resource curse," and the bill is $622,000. (For that price, you get to call yourself a "Strategic Partner.")

The FT's Gillian Tett, who has a Ph.D. in social anthropology, quotes one Davos veteran to the effect that it is a self-help group for fearful and embattled C.E.O.s. The world is an increasingly "murky, complex, and unpredictable place," Tett notes, wherein "hostility to elites is rising." At Davos, it is true, the corporate bigwigs get to chinwag, socialize, and meet with clients in peace. Following violent protests a few years back, the Swiss police now erect roadblocks halfway up the mountain, and the nasties in black ski masks are largely limited to hurling snowballs at the attendees' limousines as they whizz by. (Many people fly in by helicopter from Zurich, at a cost of $3,400 each way, thus sparing themselves any indignity.)

I wouldn't push Tett's argument too far, however. If C.E.O.s want to meet each other on the q.t., they can have breakfast at the Mayfair Regent or the Savoy. If they want some affirmation, they can agree to be profiled by Forbes or Fortune. The real key to Davos's success, and reason why it has survived for forty years, is that it has turned into what economists refer to as "a positional good"—an item or service the value of which is mostly a function of its desirability to others.

The essence of positional goods, and the reason they cost so much, is their exclusivity. An apartment at 740 Park Avenue is a positional good, so is a painting by Andy Warhol, and so is a reservation at a trendy new restaurant. The fact that you can't get in is the main reason you want to.

The same applies to Davos. If anybody (and by "anybody" I mean anybody who holds a senior job in a multinational corporation) could go—if you didn't have to be "invited" and the entrance fee were, say, a mere $10,000—it wouldn't attract the Sergey Brins, Rupert Murdochs, and Jamie Dimons of the world. The elaborate vetting procedures and stratospheric prices are ways of creating artificial scarcity. About the only people who can get in fairly easily and cheaply are journalists and heads of state, and that's because they provide so much free publicity.

Some anti-globalization protestors view Klaus Schwab, the seventy-two-year-old German economist who set up Davos forty years ago and still runs it, as the devil incarnate. I prefer to view him as a savvy nightclub promoter or restaurateur, a German version of Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, or Keith and Brian McNally. Back in the nineteen-eighties, when I first moved to New York, people used to queue around the block to get into the McNallys' latest hotspot, such as Odeon, Canal Bar, or 150 Wooster. But unless you knew the private reservation line or worked on Page Six you had little chance of securing a table.

Davos works on the same principle. The actual sessions are largely devoid of meaning, as evidenced by the recent themes of the conference. 2011: "Shared Norms for the New Reality." 2010: "Improve the State of the World: Rethink, Redesign, Rebuild." 2008: "The Power of Collaborative Innovation." I defy anybody to find any meaning in this corporate-speak gobbledygook. The point of Davos is not to learn or think or do deals, but simply to be there—and to be seen to be there. If the shareholders are picking up the tab, that's all the better.

P.S.: Dear Klaus, Re: next year's invitation. My address is: The New Yorker, 4 Times Square, New York, NY 10036.

January 21, 2011

Obama's Bailout Boys

The announcement that General Electric boss Jeffrey Immelt is replacing the former Fed chairman Paul Volcker on a revamped White House advisory board isn't exactly news, but it raises an interesting question about Obama's revamped economic team: to be admitted to a senior post, is it essential to have worked for a big financial firm that received a taxpayer bailout?

Let's consider three recent appointees:

William Daley, the new White House chief of staff. Until December, Daley, who served as Bill Clinton's Secretary of Commerce, was the top man in Washington for JPMorgan Chase, which received $25 billion from the TARP program. (In the summer of 2009, it repaid the money.) During the financial crisis, the giant bank also benefitted from a government guarantee of its debt and various emergency Fed lending programs. Although JPMorgan Chase negotiated the financial blowup more handily than some of its rivals, the government support package was key to seeing it through the worst of the crisis.

Gene Sperling, the new head of the National Economic Council. Before joining the Administration in 2009, Sperling was a consultant to Goldman Sachs, which paid him almost $900,000 for advising it on a philanthropic project in developing countries. Goldman received $10 billion from the TARP program, which it paid back in 2009. Like JPMorgan, it benefitted from a government guarantee of its debt, and, in late 2008, it was hastily granted a commercial-banking license, which made it eligible for the Fed's extensive lending facilities. Goldman has publicly denied that it would have collapsed without government assistance, but most people on Wall Street don't believe it.

Jeffrey Immelt. G.E. is usually thought of as an industrial corporation, but it is also a big bank in disguise. In recent years, its G.E. Finance arm has provided more than half of its revenues. In November, 2008, at the height of the financial crisis, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation agreed to guarantee bonds issued by G.E. Capital, and in the following seven months the firm issued almost $90 billion worth of debt that was backed by U.S. taxpayers. Without this taxpayer guarantee, which wasn't highly publicized at the time, G.E. would have struggled to roll over its debts and could even have gone under.

Now, I'm not suggesting that Daley, Sperling, and Immelt aren't capable fellows, or that they won't do a good job for the White House. Daley has politics running through his veins. Sperling is another savvy Washington operator, something his predecessor, Larry Summers, could never be accused of. (On this, read Peter Baker's story in this weekend's Times Magazine.) Immelt is a thoughtful C.E.O. who has embraced a green agenda.

Still, the fact remains: going into a tough reëlection bid, President Obama has hired three men associated with a bailout that, while economically successful, has so far proved politically poisonous. And this from a President who, according to some boneheads in lower Manhattan and Greenwich, is anti-Wall Street.

January 19, 2011

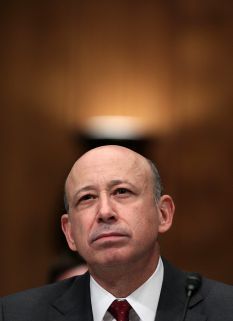

Goldman Vs. Apple: Who Generates the Highest Economic Return?

Contrary to appearances, I'm not obsessed with Goldman Sachs, and this will be my last post on the subject for a while. But the Wall Street firm issued its latest profit report today, and I thought it would be interesting to compare its results to those of Apple, another iconic American business, which yesterday published its own profit figures.

Many people are put off by financial accounts, but they provide an invaluable window into what is really going on in a given corporation, and to how much it is contributing to society. I may be weird, but sometimes I actually like poking around in 10-Qs, 8-Ks, and other disclosure forms that public companies have to file with the Securities and Exchange Commission. One word of warning, though. What follows should be considered a process of me thinking out loud, and pointing out some things that strike me, rather than reaching any definitive conclusions.

As everybody knows, Goldman and Apple are both making tons of money (although Goldman's latest results disappointed investors somewhat). In the final quarter of 2010, the bank generated net profits of $2.39 billion on revenues of $8.64 billion. Apple, which has a much bigger turnover, made profits of $6 billion on revenues of $26.4 billion.

On Wall Street and in the computer industry, quarterly profits tend to bounce around a bit, so it is perhaps more illuminating to look at the entirety of 2010. With Goldman, whose fiscal year follows the calendar, this is easy. In the past twelve months, Goldman recorded net profits of $8.35 billion on revenues of $39.16 billion. Apple's financial year ends in September, but by combining the results from its first fiscal quarter of 2011, which has just ended, and the final three quarters of 2010, I came up with the following figures. Apple made $17.63 billion on revenues of $76.28 billion.

On the face of it, the two firms' profit margins seem pretty similar. For every dollar of revenue it generates, Goldman makes a profit of about twenty-one cents; Apple makes about twenty-three cents. But that is where the comparisons end. From an economic perspective, the real measure of a business is the return it generates on the capital it employs, which could be used in alternative projects. By this metric, Apple leaves Goldman far behind.

One popular measure of capital is "shareholders' equity," which consists largely of money invested in the firm and retained earnings. Wall Street analysts tend to fixate on return on equity (ROE), but it can be a misleading, especially when applied blindly to financial institutions. In good times, banks can increase their ROE simply by taking on more leverage (borrowing). Until the fall of 2008, this was precisely the strategy that Goldman and its rivals pursued: in the boom years, Goldman often generated a return on ROE of more than twenty per cent, but this wasn't sustainable. When the credit bubble burst, high levels of leverage destroyed some banks and forced others into the arms of the government. In effect if not intention, the banks had been creating fictitious profits, much of which ultimately ended up as losses.

During the past couple of years, the banks, Goldman included, have cut their leverage ratios sharply, partly by issuing more equity to shareholders, partly by selling assets and paying down debts. As a result, we now have a more realistic estimate of their earnings power. Despite its return to profitability in 2009 and 2010, Goldman's ROE last year was just 11.5 per cent. Apple, by contrast, generated a ROE of about thirty-two per cent in 2010, almost three times the Goldman figure.

Another way to gauge a firm's performance is to take everything it possesses—its buildings, its machinery and other equipment, its product designs, and its financial holdings—and look at how much profit it generates for each dollar of assets on its books. In my opinion, this measure, which is known as return on assets (ROA), is the best way to judge a business, because it excludes the amplifying effect of leverage. Now let's apply it to Goldman and Apple.

According to its latest filing with the S.E.C., Goldman ended 2010 with assets of $911 billion, which means its ROA for the year was roughly .91 per cent. (Yes, that is less than one per cent.) Apple ended 2010 with total assets of $86.7 billion, which means it generated an ROA of about 20.3 per cent.

To summarize: Apple isn't merely generating a higher return on the capital it employs than Goldman; it is more than twenty times as profitable! How can this be?

Part of the answer is an accounting foible. Unlike some corporations, Apple doesn't record on its balance sheet much of the value of its patents and other intellectual property—the look and feel of the iPad, for example. If it did this, the figure for total assets recorded on its books would be considerably higher, and its ROA would be lower. But accounting is only a small part of the story. (As far as I know, Goldman doesn't capitalize its intellectual capital, such as it is, either.)

The main reason why Apple is so much more profitable than Goldman is a reassuring one. It makes tangible things—iMacs, iPhones, iPads—that millions of people want to buy, and for which they are willing to pay a premium price. (I am writing this post on an iMac.) Despite operating in a highly competitive industry, Steve Jobs's firm has successfully differentiated its product line to such an extent that it now has considerable monopoly power: it can charge considerably more for its gizmos that they cost to manufacture.

Goldman, for all its reputation and smarts, has no such franchise. It does some things that its clients value and are willing to pay for—making markets, raising capital, providing investment advice, hedging risky positions—but rival banks, such as JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley, provide practically the same suite of services, and pricing power is limited. (Not limited enough in some areas, such as I.P.O.s.) The only way Goldman (or any other investment bank) can increase its profit margins in a big way is to leverage up its balance sheet and live by its wits in the financial markets. But when banks all try this together, the consequences are usually disastrous.

Another thing that differentiates Goldman from Apple is how much it pays its employees. In 2010, Goldman's 35,700 employees took home an average of $430,700. Apple doesn't publish much information about its labor costs. According to the jobs Web site Simply Hired, the average salary at Apple is $46,000. Another Web site, Salary List, quotes a substantially higher figure—$107,719—but that doesn't appear to include people working at Apple's more than three hundred retail stores. Whichever number is more accurate, the basic message is the same. Apple employees earn a lot less than their counterparts at Goldman despite the fact they generate a much higher return—private and social—on the capital they use.

Go figure.

Photograph by Geoff Stearns, via Flickr, CC BY 2.0.

January 18, 2011

Goldman-Facebook: A Failure of Leadership

Updated below.

Talk about stepping on your own story! Last week, Goldman Sachs released a lengthy report (pdf) from its "Business Standards Committee" outlining thirty-nine internal reforms designed "to ensure that the firm's business standards and practices are of the highest quality; that they meet or exceed the expectations of our clients, other stakeholders and regulators; and that they contribute to overall financial stability and economic opportunity."

Yesterday, Goldman said it would be making another change—one that didn't make it into last week's report. In going ahead with its controversial plan to issue to its wealthy customers as much as $1.5 billion worth of private shares in Facebook, the bank will exclude clients resident in the United States. That's right. If you are a Russian oligarch, a Chinese entrepreneur, or a Brazilian landowner with an account at Goldman, you may well have the opportunity to get in, pre-I.P.O., on what many people on Wall Street see as the next Google. But if you made your pile in the Midwest, Silicon Valley, or Miami, forget it, bud. This deal is too hot for you, and for the Feds.

That's not how Goldman put it, of course. In a statement, it denied the Securities and Exchange Commission had put the kibosh on its hopes to issue Facebook shares to U.S. investors, saying, "The decision not to proceed in the US was based on the sole judgment of Goldman Sachs and was not required or requested by any other party. We regret the consequences of this decision, but Goldman Sachs believes this is the most prudent path to take."

Now, far be it from me to question the word of Lloyd Blankfein and his subalterns. If Goldman says the S.E.C. wasn't concerned by its efforts to circumvent the U.S. securities laws on Facebook's behalf, it must be true—even if such a version of events contradicts numerous media reports. But if Uncle Sam wasn't responsible for depriving Goldman's wealthiest American clients of the opportunity to get a bit richer, who was?

I should have known. It was those nosy, killjoy reporters (such as I) who queried the initial deal and who were intent on covering the story to its conclusion. Said today's statement: "Goldman Sachs concluded that the level of media attention might not be consistent with the proper completion of a U.S. private placement under U.S. law."

What does this mean? Over at Dealbook, Andrew Ross Sorkin fills in some details: "Federal and state regulations prohibit what is known as 'general solicitation and advertising' in private offerings. Firms like Goldman seeking to raise money cannot take action that resembles public promotion of the offering, like buying ads or communicating with news outlets."

So Goldman couldn't go ahead with the Facebook offering because it would be getting too many media inquiries? Come on. Only last week, Groupon, the group-buying Web site, raised $950 million in a private placement arranged by Allen & Co., the boutique investment bank. Extensive media coverage of that deal didn't prevent some of Silicon Valley's leading venture capital firms from plonking down almost a billion dollars, which Groupon is planning on using to fund its expansion prior to an I.P.O.

Goldman could easily have arranged a similar money-raising exercise for Facebook. However, it probably wouldn't have been able to do such a deal at a valuation of fifty billion dollars—the price it has purportedly put on Mark Zuckerberg's business. Despite Facebook's rapid growth, many venture-capital outfits would have been reluctant to buy its equity at a multiple of thirty or forty times revenues. (Estimates of Facebook's revenues range from one to two billion.) Rather than tapping the VCs at a lower valuation, Goldman decided to set up a special-purpose vehicle (i.e., a shell company) through which hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of wealthy individuals (American and foreign) would be offered the privilege of purchasing Facebook stock prior to an I.P.O.

With all due respect to Goldman and its high-priced attorneys, it wasn't a hostile media that upended this plan. It was the fact that it appeared to many people (not just reporters) to be a blatant effort to circumvent the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, which decrees that any company with more than five hundred shareholders is legally obliged to issue public financial statements, something that Facebook is keen to avoid, at least for now. Under Goldman's scheme, all the investors in its special-purpose vehicle would be counted as a single "beneficial" shareholder, thereby excluding Facebook from this disclosure provision. (An illuminating discussion of the legal niceties can be found at Dealbook.)

Having been a keen observer of Goldman for some twenty-five years (sometimes as a critic but often as an admirer of its meritocratic culture and the quality of the people it employs), little that the firm does surprises me. But this entire imbroglio has left me puzzled and raised more questions in my mind about Goldman's senior management.

It is surely fair to assume that the bright spark in Goldman's investment-banking division who came up with the original Facebook proposal hadn't seen the report of the Business Standards Committee. Let's further stipulate that when somebody more senior asked him (her) if the deal was legit, he (she) said, a) Goldman's top lawyers had signed off on it, and b) it would give Goldman a lock on Facebook's I.P.O., which many bankers expect to be the biggest (and most lucrative) yet seen in the United States.

From a narrow financial perspective the Facebook scheme was hard not to like. Under its terms, Goldman would ante up about $450 million of its own money to the social network, which is quite a sum, even for Goldman. However, it was likely to reap much more money in return. A Facebook I.P.O. sometime in 2012 that raised $20 billion, which is far from beyond the bounds of possibility, would yield some $1.4 billion in underwriting fees, at least half of which would probably go to Goldman.

And that would just be the beginning of what could well turn into another tech bubble and investment-banking bonanza. During dot-com 1.0, Goldman trailed behind its bitter rival Morgan Stanley, and ended up underwriting some famous clunkers, such as Webvan. Come dot-com 2.0, the experience of having run the Facebook book would give Goldman an invaluable lead, especially since Morgan Stanley's internet queen, Mary Meeker, has recently quit the firm. And even before the I.P.O. rush, the Facebook deal would be generating some lucrative commissions. In setting up a private (and opaque) market in Facebook shares, Goldman, as the sole market maker, was virtually guaranteeing itself some hefty margins.

That's the upside of the Facebook deal, and it's considerable. But what about the downside? Didn't anybody at Goldman consider the "reputational consequences" of helping Zuckerberg and colleagues to skirt the securities laws at time when the American public is still furious at Wall Street in general and Goldman in particular? At a time when many Americans agree with Matt Taibbi that Goldman is "a giant vampire squid wrapped around humanity"? At a time when Goldman was trying hard to dispel this perception?

Evidently, nobody took any of this into account—an oversight that amounts to a big failure of leadership.

Let's go back to last week's much-ballyhooed internal report, which was designed to draw a line under the $12.9 billion in bailout money Goldman received from A.I.G., Fabrice (Fabulous Fab) Tourre's notorious Abacus deal, and other recent embarrassments. "We must renew our commitment to our Business Principles—and above all, to client service and a constant focus on the reputational consequences of every action we take," the report declared. "In particular, our approach must be: not just 'can we' undertake a given business activity, but 'should we.' "

Another way of putting this would have been to say that Goldman, with its high profile, its recent history of having been rescued by the taxpayer, and its subsequent acquisition of a commercial-banking license, must do more than obey the letter of the law: it must act in the spirit of the law. And if that means occasionally leaving some money on the table, at least until memories fade, so be it. In pressing on with the Facebook "private I.P.O.," albeit in a slightly amended form, Goldman has strengthened the suspicion that last week's report was merely a public-relations exercise, and that the firm intends to go ahead with business as usual—or, in Taibbi's words, with "relentlessly jamming its funnel into anything that smells like money."

Moreover, if Blankfein and his colleagues thought that excluding Americans from the Facebook offering would put an end to public criticism, they had better think again. On Yahoo Finance yesterday evening, members of the peanut gallery were busy accusing it of treachery. (Sample comment: "Goldman Sachs in the future should never been given any type of bailout from the American people. They are all about greed, it is unbelievable to me that GS would even think of NOT allowing the American Taxpayer to have the right to invest in the shares of Facebook.")

Even more alarming for Goldman, there are also signs that Facebook may be edging away from its embrace. Yesterday, the Silicon Valley firm referred all questions about the latest development to Goldman. "The social-networking site's executives blame Goldman for the mess but decided to proceed with the deal anyway," the Wall Street Journal reported. Assuming the capital-raising plan goes ahead, it is now by no means certain that Facebook will stick with Goldman for its I.P.O.

Occasionally I feel pangs of sympathy for Goldmanites who, with some justification, believe they are held to higher standards than their counterparts at other banks. But that is an inevitable result of the firm's leadership position on Wall Street, the vast profits (and bonuses) it generates, and, frankly, its aggressive approach to doing business. Critics of Goldman tend to exaggerate its malevolence and its political influence; sometimes they veer perilously close to anti-Semitism. But, as this latest blowup demonstrates, the G-men (and women) are often their own worst enemy.

UPDATE, 6:30 P.M.: A source close to Goldman calls up and suggests I look at a new piece by Dealbook's legal eagle, Steven M. Davidoff, entitled "Why Did Goldman Blink?" Davidoff's line is that Goldman's decision to cancel the U.S. part of the offering was "simple risk management." Though the risk of the S.E.C. accusing Goldman of engaging in a "general solicitation" of shareholders was low, as were the chances of such a case succeeding: "The S.E.C. is under tremendous pressure these days to look relevant, and Goldman in particular does not want another clash given its reputation."

That may well be right, but I fail to see how it displays Goldman in a much better light. The fact remains that Goldman, in attempting to set up a quasi-public market for Facebook's stock prior to an I.P.O., is, to put it kindly, stretching the securities laws to their limit.

Notes Davidoff: "These markets should not exist unless the kind of information made available for a public company is made available for private companies or only investors who can truly assess the risks should be allowed to participate. This is a real debate and should spur a rethinking of how we want these markets to be regulated."

Photograph: Mark Wilson/Getty Images

January 11, 2011

The Arizona Shooting: A Mathematical Guide

Let:

A = Matches and other inflammables

B = Children

C = Irresponsible parents

D = Semi-automatic weapons

E = Alienated young men with mental problems

F = Lax gun laws

G = Fatal house fires

H = Fatal shootings

Theorem:

A + B + C = G

D + E + F = H

Proof: Trivial

QED

January 7, 2011

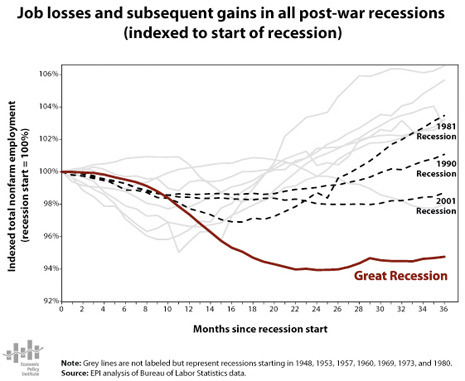

Jobs: The Crisis Continues

Whichever way you look at it, today's employment report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics was disappointing. Many people, myself included, were expecting job creation to bounce back vigorously from last month's flat figure, but it didn't. Payrolls expanded by just a hundred and three thousand in December. (Based on some encouraging private surveys, a few optimists had expected the payroll number to top two hundred and fifty thousand.)

True, the unemployment rate fell sharply—from 9.8 per cent to 9.4 per cent—but that was largely because so many jobless people have given up seeking work and dropped out of the labor force. The telling figure here is that the percentage of Americans in the labor force—the so-called "participation rate"—has fallen to 64.3 per cent, the lowest level seen yet since the recession began in December 2008.

As I've said before, one month doesn't make a trend, but seven months surely does. Since July of last year, net employment creation has topped a hundred and ten thousand—roughly the rate needed to keep up with increases in population—just once: in October, when payrolls jumped a healthy two hundred and ten thousand, according to the latest revision. Setting aside October, the job figures have been dismal. Just when the recovery should have been shifting up a gear and creating many more jobs, hiring has stalled.

In the past twenty years, we have gotten used to the phrase "jobless recoveries." There was one in the early nineties and another one in the early noughties. But as a new briefing paper from the Economic Policy Institute makes clear, the Great Recession and its aftermath is "far outside the experience of any this country has seen in 70 years."

If you doubt this is true, look at this chart:

And if you aren't depressed enough, here are a few more figures relating to the state of the labor market:

• 4.4 million—that is the number of workers who have "disappeared" from the labor force since the recession began. If all of these folks were seeking work, the unemployment rate would be about 10.7 per cent.

• 6.4 million—the number of Americans who have been out of a job for six months or more. Long-term unemployment is turning into a massive social problem. (Any unemployment person will confirm that the longer you are out of work, the harder it is to get a job.)

• 26.1 million—the number of people who are out of work or employed in part-time jobs when they would prefer to work full-time. The so-called "underemployment rate," which includes the unemployed and people working part-time involuntarily, is now 16.7 per cent, or about one in six.

On the plus side, things might turn up this month. With demand for many goods and services increasing at a steady (if relatively modest) clip, the reluctance of firms to go out and hire more workers can only last for so long.

But I also said that last month…

Chart: Economic Policy Institute

January 5, 2011

Facebook-Goldman: The Plot Thickens

Two days on, and still no official word from Goldman Sachs or Facebook about the Wall Street firm's reputed plan to invest $450 million of its own money in the social network, and to raise from its rich clients up to $1.5 billion that would also be destined for Mark Zuckerberg's firm. However, in the absence of hard information, there is no shortage of reporting and comment about a proposal that some lovers of oxymorons have dubbed "a private I.P.O."

Several outlets have reported that the Securities and Exchange Commission is looking closely at the Facebook-Goldman link-up. On Fox Business Channel today, Charles Gasparino, the veteran Wall Street gumshoe, reports there is a fifty-fifty chance of S.E.C. regulators nixing the deal. "What they are telling people is that this is not a done deal," Gasparino said. "Despite everything you are reading in the paper, they haven't given their blessing."

As I pointed out on Tuesday, the Goldman proposal appears to be designed to skirt regulations governing how far private companies can go in raising money from individual investors. As such, it represents an embarrassing poke in the eye to the S.E.C. and its head, Mary Schapiro.

In an article at Dealbook, which broke the original story, Steven M. Davidoff, an attorney at Shearman & Sterling, lays out the legal situation with admirable clarity. The relevant statute is Section 12(g) of the Securities Exchange Act, which says that any business with assets exceeding a million dollars and more than five hundred "shareholders of record" must register its securities with the S.E.C. In my original article, I went too far in saying such companies are obliged to hold an I.P.O. and issue stock to the public. Private companies with more than five hundred shareholders can choose to remain private. But they are legally obliged to file audited quarterly financial reports with the S.E.C., which, effectively, strips them of the privacy that Zuckerberg clearly covets. According to many accounts, it was this public reporting requirement that prompted Google and Microsoft to go the full hog and become public companies.

Goldman may well argue that this rule doesn't apply to Facebook. Because its clients will be buying shares in a special purpose vehicle, which, in turn, will purchase shares from Facebook, they won't be "shareholders of record," but merely "beneficial owners" of a managed investment pool that counts as just stockholder. But, as Davidoff points out, the Section 12(g) gives the government powers to deal with precisely this type of legal wheeze. The law states: "If the [company] knows or has reason to know that the form of holding securities of record is used primarily to circumvent the provisions of [the Securities Act], the beneficial owners of such securities shall be deemed to be the record owners thereof."

So would the Goldman proposal break the law? This is Davidoff's opinion: "(W)hatever you might think of the rule itself, Goldman's planned special purpose vehicle and any other vehicles formed certainly appear to be cutting it close. Legally, it appears the S.E.C. would have grounds to force Facebook to begin reporting its financial results publicly if indeed the Goldman vehicle puts Facebook over the 500-person threshold."

According to Gasparino, the S.E.C. is determined to intervene, the only question being how it does so: "If they don't nix this deal, they are going to do some rules in the future that could nix future deals. Even if it does go through, the SEC is going to clarify this public/private thing and how many investors you can put in there. From what I understand, they aim to make this the last deal of its time."

John Cassidy's Blog

- John Cassidy's profile

- 56 followers