John G. Messerly's Blog, page 34

September 5, 2021

Owen C. Middleton (convict 79206) and the Meaning of Life

In 1930 the historian and philosopher Will Durant—who was at that time a famous public intellectual—received a number of letters from persons declaring their intent to commit suicide. The letters asked him for reasons to go on living. In response Durant asked a number of luminaries for their views on the meaning of life, publishing those responses in his 1932 book, On the Meaning of Life .

.

As the manuscript was being prepared for publication, Durant received a letter from “Convict 79206” at the Sing Sing maximum-security prison in New York. The convict had been recently sentenced to life in prison and Durant published the letter as an appendix to the above-mentioned book. Of its contents, Durant wrote: “It is incredible that we should be unable to find any better use for such intelligence than to lock it up forever.”

Convict 79206’s response is too long to print here, but we can highlight a few of its points. He argued that suicide would be permissible for those who found life meaningless, but that he had not yet reached that point. He maintained that life was accidental but not necessarily meaningless. He was not religious and advised against seeking “comfort in delusions, false tradition, and superstition.” He discussed the difference between truth, which is neither beautiful nor ugly, and belief “the idol-worshiping strain in our natures.” He said that “happiness is a state of mental contentment [which] can be found on a desert island, in a little town, or the tenements of a large city.” And he was optimistic about the future:”[Humans are] an integral part of the universe in which [they] live, that universe which is ever-moving forward to some appointed destiny.”

At the end of the letter, before heading back to live what most of us would assume is a futile and meaningless existence, convict 79206 painted a picture with his words. Through them, his dignity, integrity, and strength of character shone forth.

This evening I stood in the prison yard amid other prisoners, with eyes lifted aloft gazing at that great … airship … as it sailed majestically over our heads. Into my mind came the thought that, just as that prehistoric creature struggled up out of the sea to the land, so is man struggling up from the land into the air. Who dare deny that, some day, up, ever up he will struggle thru the great reaches of interstellar space to wrest from it the knowledge which will enable him to lift his life to a plane as high above this, our present one, as it is above that of prehistoric man?

I do not know to what great end Destiny leads us, nor do I care very much. Long before that end, I shall have played my part, spoken my lines, and passed on. How I play that part is all that concerns me.

In the knowledge that I am an inalienable part of this wonderful, upward movement called life, and that nothing, neither pestilence, nor physical affliction, nor depression, nor prison, can take away from me my part, lies my consolation, my inspiration, and my treasure.

Owen C. Middleton (convict 79206) was a transhumanist before his time and a man of greater depth and humanity than most. How much potential wastes away in our prisons.

August 29, 2021

Children and Meaning

[image error]

A good friend wrote me recently. He said that his twelve-year-old son has begun to wonder if life is meaningless and if death ruins the joy of life. This is an intelligent, athletic, handsome young man with loving, highly educated, and economically successful parents, living in a first world country. Truth be told this young man’s grandfather has recently die and his grandmother is gravely ill. But even absent these tragedies, the question inevitably arises. Why is this?

WHY DO WE WANT TO KNOW IF LIFE IS MEANINGFUL?

The question of the meaning of life arises for almost anyone who begins to think. As Camus said, “beginning to think is beginning to be undermined.” The desire to make sense out of life is a primary motivator of human life. As the famous cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz said: “The drive to make sense out of experience, to give it form and order, is evidently as real and pressing as the more familiar biological needs.” Thus the question emanates, in part, from a deep wellspring of biological and psychological need; the need to answer the question springs from our nature, reaching in some sense into the genome itself.

The other source for the question is undoubtedly our historical, cultural, social and family environments. What is happening at this moment in history, culture, society, and family elicits and frames the question of meaning in a certain way. And, given that the question of life’s meaning only became a prominent one in western civilization in the 19th century, it is reasonably to think that there is something about secularism and modernity that has brought the question to the surface. Philosophers as diverse as Habermas, Nagel, Dworkin, and Charles Taylor all argue that something is missing in the secular world, while religious thinkers as diverse as the Dalai Lama, Gandhi, and John Fire Lame Deer believe that consumerism, capitalism, and materialism leave many bereft of hope and meaning.

Thus the general answer to a question about human thought and behavior is always some combination of nature and nurture, of a genome in an environment. Of course, a specific case of an obsession with the question could emerge from psychological maladies like depression or anxiety, although we shouldn’t draw this conclusion too quickly. Asking about meaning is often a mark of an authentic human life, not of a mental disease.

THE ANSWER IS FOUND IN SOMETHING LARGER THAN OURSELVES

I have written at length on this blog and in my book about meaning in human life. There are many ways to derive it, and all sorts of people live what they believe are meaningful lives. But one idea that comes up constantly is to place our lives in a larger context. For example, Bertrand Russell said he overcame the fear of death when he let the walls of his ego recede, and saw himself in a larger context. The things he cared about: truth, beauty, goodness, knowledge and all the rest would be pursued without him. The historian and philosopher Will Durant suggested something similar:

If we think of ourselves as part of a living … group, we shall find life a little fuller … For to give life a meaning one must have a purpose larger and more enduring than one’s self. If … a thing has significance only through its relation as part to a larger whole, then, though we cannot give a metaphysical and universal meaning to all life in general, we can say of any life in the particular that its meaning lies in its relation to something larger than itself … ask the father of sons and daughters “What is the meaning of life?” and he will answer you very simply: “Feeding our family.”

To better understand consider that the meaning of a movie or painting is difficult to discern if you see only a small part of them. If I only see a few moments of the movie or a few brushstrokes of the painting, I can’t understand them as well as if I see the whole thing. Of course, we might see the whole movie or painting and still find them meaningless. But it is somewhat comforting to know that if we saw the entire movie or painting—or the past and future of all reality—then we might be able to understand their meaning. If there is meaning to the life, the universe, and everything then it must come from a perspective we now lack. This means the problem might not be that the universe lacks meaning, but that we lack the proper perspective.

SHOULD IT BOTHER US THAT WE CAN’T ANSWER THE QUESTION?

Some might reply that it is not comforting but depressing to lack the universal perspective needed to make a determination about meaning. Should we respond like this? In some sense we should, because our dissatisfaction pushes us to do whatever it takes to answer our questions. On the other hand, we must accept that we do not now have all the answers we desire, and probably will not get them in our lifetime. Life calls upon us to learn to live without being sure. It is a hard lesson and most never learn it. But the honest and courageous live with ambiguity and without answers—they live authentically.

In my next post, I will quote at length from a 1932 letter from a convict sentenced to life in prison on the meaning of life.

August 22, 2021

The Millions Of Christs Of America

(Akim Reinhardt’s superb essay about the proliferation of conspiracy theories online was published at 3 Quarks Daily on MONDAY, AUG 16, 2021. Reprinted with permission.)

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

As an undergraduate History major, I reluctantly dug up a halfway natural science class to fulfill my college’s general education requirement. It was called Psychology as a Natural Science. However, the massive textbook assigned to us turned out to be chock full of interesting tidbits ranging from optical illusions to odd tales. One of the oddest was the story of Leon, Joseph, and Clyde: three men who each fervently believed he was Jesus Christ. The three originally did not know each other, but a social psychologist named Milton Rokeach brought them together for two years in an Ypsilanti, Michigan mental hospital to experiment on them. He later wrote a book titled The Three Christs of Ypsilanti.

Rokeach hypothesized that since Jesus exists by the same code that the Immortals in Highlander later stated as “There can only be one,” these three men might be cured of their delusions when confronted with others who insisted likewise. Of course he was very wrong. Much like Highlander’s Immortals, they simply fell into conflict. When faced with the others’ unrelenting presence, each dug their heels in and doubled down on their delusions. Even Rokeach’s jaw-dropping manipulations, which included a string of outrageous lies and elaborate fabrications, could not dissuade them.

I’ve recently been pondering this infamous tale of poorly conceived psychological experimentation because in it I see reflections of problems currently plaguing America. Except instead of being thrown together in confinement, people with similar mental disorders are now finding each other on their own. And instead of a psychological professional at least trying (albeit in a highly flawed manner) to cure them, the medium of connection is the largely unregulated and even more manipulative internet. And, finally, instead of insisting there can only be one, mentally ill people are now reinforcing and reduplicating each other’s delusions.

Of course you don’t have to be mentally ill to believe most of the world wide web’s whack-a-doo conspiracy theories. One need merely be stupid or gullible, or in most cases perhaps, just a bit desperate. Take for example the entirely discredited “theory” that childhood vaccines cause autism. It is very understandable that the trauma of conceiving and parenting a severely autistic child would break someone just a little bit, to the point that they demand an explanation that satisfies them more than what we currently know about autism’s causes, which is very little. For some, “very little” just won’t do. Furthermore, the little we do know, including that genetics might be a factor, may contribute to a sense of misplaced guilt that some simply cannot shoulder, leading them to grasp at whatever else is out there. And what’s out there is an internet-fueled story about vaccines.

Funnel it through the internet, and suddenly it’s the conspiracy theory that’s infectious, spreading from the desperate to the naive. By 2011, 18% of Americans believed this incredibly dangerous hooey. That’s roughly 50 million people.

Likewise, you don’t have to be mentally ill to sincerely believe that the Earth is flat, that the Holocaust is a hoax, that the moon landing was faked, that Princess Diana was murdered, that 9-11 was an inside job, or that JFK was killed by the CIA or the Mafia or the Cubans. You might very well be mentally ill. But you don’t have to be.

However, as we move up the ladder to more and more ludicrous internet conspiracy theories, it begins to seem as if some sort of mental illness is a prerequisite for full faith. That is not a professional assertion. Psychology as a Natural Science was a fun course, but not life changing. I stuck with my major and became a Historian, not a mental health professional, and I respect professional boundaries. But just as any reasonable person can make lay interpretations about the past, any reasonable person can conclude that your brain must not be working properly if you sincerely believe that the world’s leading politicians, business leaders, and artists are actually blood-sucking Lizard People from outer space responsible for the Holocaust and 9-11, and hell bent on ruling the world and enslaving humanity.

The appropriate lay word here would be “crazy.” That’s what I said to my partner about a new friend who began sending her Lizard People conspiracy theory emails. Not as a joke, which is what my partner first assumed. But as educational material. As in, this is real. “Your new friend is crazy,” I told her. “Stop hanging out with her.” She did. Yet the emails about Lizard People and other lunacy continued. So she blocked her.

But of course it’s not so simple. At least not for us as a society. This isn’t about just three avatars of Christ locked up in an Ypsilanti hospital, with any other people clinging to the same delusion scattered and isolated across the country. There are hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions who believe either in Lizard People or other outrageous conspiracies. And they are not scattered. They are not isolated. They are finding each through the internet, where they reinforce and expand their delusions and recruit new believers, just as this woman attempted to recruit my partner. They are voting. They are running for office. They are serving in Congress. They were among those who stormed the Capitol at the president’s urging, and attempted to violently overturn a national election.

It wasn’t always this way, even when it was.

Here in the United States, Boomers and Gen Xers remember the “newspapers” one used to find for sale at the supermarket checkout aisle. Classic impulse buys, they were pure frivolity that no right-thinking person would put into their basket while hunting for food to sustain yourself and your family. Rather, you might buy it on a lark now that the brunt of the chore is done, as you unload your items onto the conveyor belt and begin to realize you’re actually under your budget. Why not buy something silly like watermelon flavored diet breath mints? Or a cheap, little toy your kid is wound up about? Or a some celebrity gossip rag? Or better yet, some absolutely ridiculous piece of trash like the Sun or Weekly World News, with their mix of weird-but-true stories, and completely fabricated yarns.

Inside their pages you would find the reliable, stock folk tales, such as Big Foot and the Loch Ness Monster. Then there was the in-house taradiddle, such as explorers finding The Garden of Eden; or Bat Boy, the half-bat, half-human child living in a West Virginia Cave; or various space aliens, including one named P’lod who was having an affair with Hilary Clinton. Who would actually believe such fatuousness?

Just about everyone knew these were jokes, and those who were gullible enough to believe them generally kept quiet about it. After all, when everyone around you says this is a joke, you might just give up on it. Or at least keep it to yourself rather than face the inevitable mockery.

However, one of these tongue-in-cheek absurdities struck a chord. When the WWN ran a story claiming that the dearly departed, gone-far-too-young Elvis Presley was still alive, it resonated with readers. It must have been something about Elvis; similar stories about JFK, Marilyn Monroe, Hank Williams Sr., and Adolph Hitler still being alive didn’t generate anywhere near the same buzz. But the Elvis story took off. People laughed. Soon it was a running joke for Johnny Carson, David Letterman, and other comedians. A pre-web meme had been born.

However, one of these tongue-in-cheek absurdities struck a chord. When the WWN ran a story claiming that the dearly departed, gone-far-too-young Elvis Presley was still alive, it resonated with readers. It must have been something about Elvis; similar stories about JFK, Marilyn Monroe, Hank Williams Sr., and Adolph Hitler still being alive didn’t generate anywhere near the same buzz. But the Elvis story took off. People laughed. Soon it was a running joke for Johnny Carson, David Letterman, and other comedians. A pre-web meme had been born.

For most people, the notion of a gray-haired Elvis sneaking in and out of movie theaters was so preposterous that it became something funny to spoof. Yet some people insisted it was true. When the story fist came out, WWN offices, much to their surprise and delight, fielded dozens of phone calls from people wanting to know more. Some were willing to believe that Elvis wasn’t really dead after all.

Given that the entire Christian religion, with its two and a half billion believers, is predicated on more or less the same thing, I guess it’s understandable.

No, I did not just say that every theistic religious adherent is mentally ill. The actual nature “mental illness” as a socially constructed category is for another time. Rather, the point is that back in the late 20th century, while some people could still fall for a brand new shenanigan such as Elvis is alive!, the popular purveyors of poppycock were not powerful enough to spread genuine conspiratorialism very far. Yes, there were some who believed Elvis was still alive, but their numbers were contained. Straight faced rags like the Weekly World News and the Sun could turnout only so many true believers because anyone seriously subscribing to their silliness still lived in a society that indulged these tales only to lampoon them. Either you were mocking or being mocked; and having nearly everyone mock you is a serious inhibitor.

But the internet is not just a few small publications available only at grocery checkout aisles. It is, for practical purposes, infinite, and nearly as omnipresent as one wants it to be. Worse yet perhaps, it is algorithmic. More and more of it is intentionally designed to find you, grip you, and draw you together with both, like minded people and manipulative bots coded to feed your frenzy. There are now fellow Christs from Ypsilanti everywhere, and countless Dr. Rokeaches, none of them manipulating you in pursuit of a cure but only to reinforce your misbeliefs so as to profit from them politically and/or economically.

The tide has turned. Instead of 99% of America mocking your outlandish beliefs, and perhaps no one you personally know agreeing with them, the internet connects believers and reinforces and spreads beliefs. Many people you know online, and even in person, now agree with you completely. Under these circumstances, the conspiracies become infectious, spreading from those who are susceptible because of mental illness to those who get caught up in the craze, much like the roughly 50 million Americans who eventually believed, casually or deeply, in the autism vaccine conspiracy. At least that one had an air of faux science about it. Now we’re nearly overrun by far fetched lunacy.

The exact numbers are impossible to discern, but whatever the tally, it is far too high. People joining together around their belief in Lizard People from space enslaving us. Or that Hilary Clinton (she does seem a popular target for this claptrap) and other top Democrats ran a child sex trafficking ring from the basement of a Washington D.C. pizzeria located in a building that literally has no basement. Or that the mass shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary and Marjory Stoneman Douglas High were faked, and that student survivors and parents of murdered grade schoolers are actually paid “crisis actors.”

No matter how crazy they are, there’s a special place in Hell for people who harass the parents of murdered seven year olds.

But it’s probably somewhere between Lizard People and the faux science of vaccine autism where the real danger lies. Despite mountains of evidence against the conspiracy and none for it, 32% of Americans, including 53% of Republicans believe Donald Trump lost the 2020 presidential election only because of massive voter fraud. Say otherwise and face their wrath. It doesn’t matter who you are. Even a Trump-loving, war veteran, sitting Republican Congressman who denies the conspiracy becomes a target of public scorn.

Now you’re the one being mocked.

Akim Reinhardt’s website, which collects no data, does not track you, makes no effort to join you with the likeminded, and pedals only the bestest conspiracies, is ThePublicProfessor.com

August 15, 2021

Love and Death

[image error]

Many people believe that dying is like moving to a better neighborhood. This is not surprising, as belief in the afterlife is widespread. To sustain this belief, people cling to any indirect evidence they can—near-death experiences, tales of reincarnation, stories of ancient miracles, supposed communication with the dead, pseudo-scientific studies, and the like. But none of this so-called evidence stands up to critical scrutiny. Many believe, not because there’s good evidence, but because they want to.

Yet such faith is hard to sustain. Every single moment we are alive confirms at least one truth—those who are dead are dead. We may hear the voices of the deceased in our heads, but we don’t take the departed out to lunch. We could live in a world with evidence for the afterlife—for example, one where the dead regularly appeared and described post-mortem existence—but we don’t. Belief in the afterlife is probably just wishful thinking.

As for science, it generally ignores the so-called evidence of an afterlife for many reasons. First, the idea of an immortal soul plays no explanatory or predictive role in the modern scientific study of human beings. For instance, doctors no longer attribute mental illness to demonic possession of our souls—only Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia and the scientifically illiterate do that.

Second, the overwhelming evidence suggests that consciousness ceases when brain functioning does. If ghosts or disembodied spirits exist, then we would have to abandon scientific ideas that we hold with great confidence—like the notion that brains generate consciousness. In fact, the idea of a soul is incompatible with everything we know about modern physics—best-selling books to contrary just prey on human credulity.

Professional philosophers also tend to be skeptical of the afterlife, as good arguments for it are virtually non-existent. Moreover, almost all philosophers today are physicalists

regarding the mind. This means that mind—or soul if it even exists—depends on the body. In other words, when the body dies our consciousness is extinguished; there is no ghost in the machine.

Of course, this cursory treatment doesn’t establish the impossibility of an afterlife; after all, reality is mysterious. Still, given what we know about how our brains work, disembodied consciousness is unlikely. Clearly, the scientific and philosophical winds blow against such ancient beliefs, and people increasingly reject belief in god, miracles, and the afterlife.

But if death is the end, how should we feel about it? We might be undisturbed by death, finding consolation in the words of the Greek philosopher Epicurus: “When I am, death is not; and when death is, I am not.” Epicurus taught that fear of the gods and death is irrational. If we think about death, we will see that it’s not bad for us since we have no sensations when we are dead. Yes, the process of dying can be bad, and our deaths may hurt others, but Epicurus argued that death can’t be bad for the deceased. For how can what we don’t know hurt us?

We could reject this argument, claiming that we can be harmed by something without being aware of it. For example, intelligent adults reduced to the state of infancy by a brain injury suffer great misfortune, even if unaware of their injurious state. Perhaps the dead are similarly harmed. But we can still ask, how can the dead be harmed? Perhaps Epicurus is right, after all, death shouldn’t trouble us.

Yet despite Epicurus’ argument, we may still find the idea of our death unsettling. For one day the sun will set for the very last time for us, and every thought and memory we have ever had will … vanish. When we are gone we will no longer read books, take trips, or hear familiar voices. We will never take another walk, catch another baseball, or play in the snow. We won’t know about new music, inventions, ideas or what will happen to our children or grandchildren. This is why we don’t want to die.

In response, we could hope that science and technology save us, and there are plausible scientific scenarios whereby death might be overcome. Still, such technology probably won’t be developed in time to avoid our own deaths. We could also buy a cryonics policy, but there are no guarantees this would work, or that we would wake up in a reality that we would want to live in.

Moreover, even if we did extend our lives indefinitely, the universe itself is doomed. In that case, life seems pointless. For how can anything matter if all ends in nothingness? The only way around this conclusion is if our descendants become gods and somehow escape the death of the cosmos. Unfortunately, such fantastic futures aren’t only unlikely, they also don’t comfort us when we look at our spouse or our children and realize that someday we’ll never see them again. Never. Death doesn’t care about our desires; our attitude toward death appears irrelevant; raging against death seems futile. As Philip Larkin wrote:

… Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

For now, with the reality of death looming, resignation and acceptance probably serve us best. Yet we can find some consolation—all is not lost. For if our interests are large enough, if we detach ourselves from the concerns of our little egos, if we identify with something large like the future of cosmic evolution, then there is a good chance that what we care about will continue. Maybe such thoughts can lessen the sting of death.

Most importantly, if we truly feel the reality of death, we might be kinder to each other. If the thought of our non-existence has any value, this may be it. For all the pain we cause each other is pointless against the backdrop of eternal nothingness. If we are all dying together, why not be nicer to each other, why not fill our little time with less pain? Maybe, if we could see ourselves from this cosmic point of view, we could even say with the poets, that what survives of us is love.

This may be too poetic, and it may not be all we want. But love is remarkable. It appears in a world of cruelty and savagery, in a species whose roots are “red in tooth and claw.” Love brings the peace of knowing that someone cares for us, waits for us, listens to us. In the unfathomable infinity of space and time, in the infinite cold and darkness which surrounds us … love relieves loneliness, love connects us, love sustains us. And perhaps the traces of our love do somehow reverberate through time, in ripples and waves that one day reach peaceful shores now unbeknownst to us. Perhaps love doesn’t disappear into nothingness; perhaps love can be perfected; perhaps love is stronger than death.

August 11, 2021

My Academic Geneology

I received my Ph.D. in philosophy in 1992, completing my dissertation under the direction of Richard J. Blackwell, who at the time held the Danforth Chair in Humanities at Saint Louis University. He is currently Professor Emeritus. Professor Blackwell (1929 -) was educated at MIT, (where he studied history and physics) and St. Louis University, where he received his Ph.D. in philosophy in 1954. After a short stint in the philosophy department at John Carroll University in Cleveland, he came back to St. Louis University in 1961.

Professor Blackwell is an authority in the history of philosophy, the history and philosophy of science, and is one of the world’s foremost experts on the Galileo affair. In addition to his outstanding record of scholarly achievement, Professor Blackwell directed more than 30 dissertations during his tenure at St. Louis. His Ph.D. students include Robert J. Richards (Chicago) Gary Gutting (Notre Dame, 1942- 2019); and Dominic Balestra among others.

Professor Blackwell’s dissertation, Aristotle’s Theory of Predication, was completed under the direction of Leonard J. Eslick. Professor Eslick, who died in 1991, received his Ph.D. at the University of Virginia in the early 1930s. I met him once at a Christmas party where he told me that Professor Blackwell was the best student he ever had.

I was especially influenced by Professor Blackwell’s belief that philosophical thinking uninformed by modern science—particularly physics and evolutionary theory—was superfluous. Through a series of his seminars, I came to realize that physical, mental, social, biological, and cosmic life all evolve. This led me to conclude that through the process of development lies the only viable hope for humankind and their post-human descendants. Moreover, his even temper and gentlemanly manner inspire me to this day. I will forever be indebted to him for his contribution to my education.

I was also influenced by Professor William C. Charron. He is an authority on game theory, modern philosophy, social and political philosophy, and the literature and philosophy of T.S. Eliot. His clarity of mind and love of the craft of writing still influence me today.

August 4, 2021

Tolstoy: “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”

Leo Tolstoy’s short novel, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, provides a great introduction to connection between death and the meaning of life. It tells the story of a forty-five year old lawyer who is self-interested, opportunistic, and busy with mundane affairs. He has never considered his own death until disease strikes. Now, as he confronts his mortality, he wonders what his life has meant, whether he has made the right choices, and what will become of him. For the first time he is becoming … conscious.

The novel begins a few moments after Ivan’s death, as family members and acquaintances have gathered to mark his passing. These people don’t understand death, because they cannot really comprehend their own deaths. For them death is something objective which is not happening to them. They see death as Ivan did all his life, as an objective event rather than a subjective existential experience. “Well isn’t that something—he’s dead, but I’m not, was what each of them thought or felt.” They only praise God that they are not dying, and immediately consider how his death might be to their advantage in terms of money or position.

The novel then takes us back thirty years to the prime of Ivan’s life. He lives a life of mediocrity, studies law, and becomes a judge. Along the way he expels all personal emotions from his life, doing his work objectively and coldly. He is a strict disciplinarian and father figure, the quintessential Russian head of the household. Jealous and obsessed with social status, he is happy to get a job in the city where he buys and decorates a large house. While decorating he falls and hits his side, an accident that will facilitate the illness that eventually kills him. He becomes bad-tempered and bitter, refusing to come to terms with his own death. As his illness progresses a peasant named Gerasim stays by his bedside, becoming his friend and confidant.

Only Gerasim shows sympathy for Ivan’s torment—offering him kindness and honesty—while his family thinks that Ivan is a bitter old man. Through his friendship with Gerasim Ivan begins to look at his life anew, realizing that the more successful he became, the less happy he was. He wonders whether he has done the right thing, and comprehends that by living as others expected him to, he may not have lived as he should. His reflection brings agony. He cannot escape the belief that the kind of man he became was not the kind of man he should have been. He is finally experiencing the existential phenomenon of death.

Gradually he becomes more contented and begins to feel sorry for those around him, realizing that they are too involved in the life he is leaving to understand that it is artificial and ephemeral. He dies in a moment of exquisite happiness. On his deathbed: “ It occurred to him that his scarcely perceptible attempts to struggle against what was considered good by the most highly placed people, those scarcely noticeable impulses which he had immediately suppressed, might have been the real thing, and all the rest false.”

Tolstoy’s story forces us to consider how painful it is to reflect on a life lived without meaning, and how the finality of death seals any possibility of future meaning. If, when we approach the end of our lives, we find that they were not meaningful—there will be nothing we can do to rectify the situation. What an awful realization that must be. It was as if Kierkegaard had Ilyich in mind when he said:

This is what is sad when one contemplates human life, that so many live out their lives in quiet lostness … they live, as it were, away from themselves and vanish like shadows. Their immoral souls are blown away, and they are not disquieted by the question of its immortality, because they are already disintegrated before they die.

Now consider an even more chilling question. What difference would it make even if a life had been meaningful? Wouldn’t death erase most, if not all, of its meaning anyway? Wouldn’t it be even more painful to leave a life of meaningful work and family? Perhaps we should live a meaningless life to reduce the pain we will feel when leaving it? But then that doesn’t seem right either.

Summary – Confronting the reality of death forces us to reflect on the meaning of life.

____________________________________________________________________

Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich (New York: Bantam Books, 1981), 37.

Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Chapter XI.

Soren Kierkegaard, “Balance between Esthetic and Ethical,” in Either/Or, vol. II, Walter Lowrie, trans., (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1944).

July 28, 2021

“Settling” for a Romantic Partner

[image error]

A problem for many, especially the young, is that when they seek long-term partners they are moved by sexual passion and physical desire. They often fail to seek substantive people with whom they can experience a lasting, mature love based on compromise, tolerance, stability, and commitment. I realize this is trite advice, and I also acknowledge this thought didn’t occur to me when I was in my twenties. Still, it is surprising how many disregard this advice. Here is an example.

Before a college class about twenty years ago two young female students were discussing the movie “Sense and Sensibility,” which is based on Jane Austen’s novel of the same name. In the movie, the beautiful Marianne Dashwood immediately falls madly in love (lust) with the dashing John Willoughby. Here is the scene as they first meet. Marianne has hurt her ankle and the strong, dashing Willoughby has carried her home. “He lifted me as if I weighed no more than a trite leaf,” she says. She is smitten.

As for the wealthy, stable, but older and less dashing Colonel Brandon, who dearly loves Marianne, she has no use. Marianne has mistaken her passionate enthusiasm for love, and, shortly thereafter, Willoughby discards her for a more wealthy patron.

Finally, she begins to realize that Willoughby loves money more than he loves her—she realizes that Willoughby is more form than substance. She eventually marries the Colonel and by all accounts, they have a happy, stable marriage built on mutual love and respect. (The character of David Copperfield in Dickens’ novel has a similar experience. He marries his longtime, sensible friend Agnes and finally finds true happiness.)

My two young female students found this outcome disappointing if not downright depressing. Marianne shouldn’t have “settled” for the Colonel they told me. She should have waited for a better man. My rejoinder? The Colonel was only rich, kind, wise, just, stable, honest, smart, and good-looking. What a terrible husband he would make! But why couldn’t the beautiful Marianne find all that in a man as handsome, passionate, and strong as Willoughby, my young students wondered? By contrast, I doubted if a man as good as the Colonel even existed. I concluded that these young women had an immature and naive view of romantic love. Somehow the Colonel fell short of their ideal mate—a mate that doesn’t exist. My young students wanted to marry a chimera.

Many people, especially young ones, foolishly reject potentially good mates for those who only seem good, as Willoughby appeared to Marianne. And this is partly why the Greeks thought erotic passion was dangerous and irrational. It clouds our judgment and misleads us. We are naturally drawn to external beauty and passion, often missing a deeper beauty right in front of us. Our senses detect external beauty and physical passion, but our good sense, our sensibility, determines if a person is truly beautiful. Hence the title of the novel.

Jane Austen’s message is that we should seek true beauty. Fortunately, in the end, Marianne becomes wise. She recognizes the serenity, if not the unending passion, of true love.

“For whatsoever from one place doth fall,

Is with the tide unto another brought:

For there is nothing lost, that may be found, if sought.”

― Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene

July 24, 2021

New Quotes Page

[image error]

What is wanted is not the will-to-believe, but the wish to find out, which is its exact opposite. ~ Bertrand Russell

My wife has made my quotes page easier to navigate. At the top of the page, all quote topics are listed and linked to. That way readers can know the quote topics and easily navigate to them.

I really like good quotes as they get to the heart of an issue in few words. Great quotes have always made a clear and memorable imprint in my mind—someday I’d like to write a book using mostly quotes to explain much of my philosophy. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy perusing my collection of quotes that have been amassed from a lifetime of reading.

Finally, I would like to thank Jane for the hours she spent on the quotes page and for all the work she has done through the years on the website. I have no facility in programming whatsoever so this site is as much hers as it is mine. There would be no site without here. Thank you Jane.

July 21, 2021

Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us

The basic ideas of Daniel Pink’s Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us have entered the intellectual mainstream, but they haven’t had much impact upon the world of work. This is a shame.

have entered the intellectual mainstream, but they haven’t had much impact upon the world of work. This is a shame.

The key insight of Pink’s research is that money only motivates employees up to a certain point, beyond which it no longer works as a motivator. This does not mean that employees do best when paid low wages—everyone needs enough to live a decent human life—but it does mean that beyond a certain point people aren’t motivated by more money. After a certain point, intrinsic motivation, which comes from within yourself is much more powerful than extrinsic motivation, which comes from outside sources like money.

What people really want from work is: 1) autonomy: self-directed control over their work; 2) mastery: the chance to get better at our work; and 3) purpose: a reason to be motivated to do our work. The key is to pay people enough so that they aren’t thinking about money but thinking about work. And once you do that, the science shows that giving workers the autonomy to master and find purpose in their work will lead them to being happier and more productive. Here are links to all of Pink’s books about work:

July 14, 2021

The Road Not Taken Wasn’t Meant To Be Serious

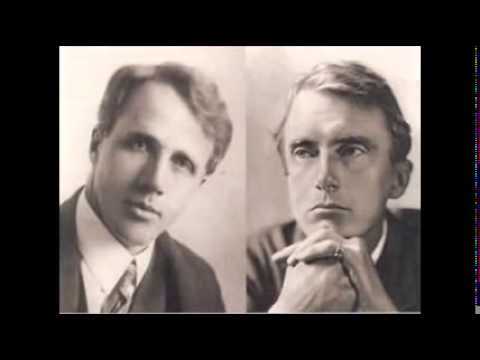

Edward Thomas and Robert Frost

Edward Thomas and Robert Frost

Robert Frost’s poem, “The Road Not Taken,” is probably America’s best-loved poem. It is a lyrical delight and I long ago committed it to memory. What is less well-known is the origin of the poem:

Frost spent the years 1912 to 1915 in England, where among his acquaintances was the writer Edward Thomas. Thomas and Frost became close friends and took many walks together. After Frost returned to New Hampshire in 1915, he sent Thomas an advance copy of “The Road Not Taken.”[1] The poem was intended by Frost as a gentle mocking of indecision, particularly the indecision that Thomas had shown on their many walks together. However, Frost later expressed chagrin that most audiences took the poem more seriously than he had intended; in particular, Thomas took it seriously and personally, and it provided the last straw in Thomas’ decision to enlist in World War I.[1] Thomas was killed two years later in the Battle of Arras.[2]

The tragedy of this misunderstanding is poignant. Thomas was himself a wonderful writer. As evidence, here are the final lines from his short story “The Stile.”

I knew that I was more than the something which had been looking out all that day upon the visible earth and thinking and speaking and tasting friendship. Somewhere — close at hand in that rosy thicket or far off beyond the ribs of sunset — I was gathered up with an immortal company, where I and poet and lover and flower and cloud and star were equals, as all the little leaves were equal ruffling before the gusts, or sleeping and carved out of the silentness. And in that company I learned that I am something which no fortune can touch, whether I be soon to die or long years away. Things will happen which will trample and pierce, but I shall go on, something that is here and there like the wind, something unconquerable, something not to be separated from the dark earth and the light sky, a strong citizen of infinity and eternity. The confidence and ease had become a deep joy; I knew that I could not do without the Infinite, nor the Infinite without me.

Edward Thomas was killed on the first day of the battle of Arras, Easter 1917, surviving just over two months in France. He was survived by his wife and three young children.

War is, for the most part, futile.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I —

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

(This post first appeared on November 11, 2014, the anniversary of Armistice Day.)