John G. Messerly's Blog, page 30

January 6, 2022

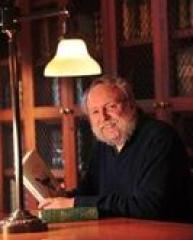

Review of Michael Ruse’s “A Philosopher Looks At Human Beings

Michael Ruse (1940 – ) is one of the world’s most important living philosophers. He currently holds the Lucyle T. Werkmeister Professor and is Director of History of Philosophy and Science Program at Florida State University. He is the author of more than 50 books, a former Guggenheim Fellow and Gifford Lecturer, a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and a Bertrand Russell Society award winner for his dedication to science and reason. He has also received four honorary degrees.

Ruse’s newest book A Philosopher Looks at Human Beings so captivated me that I finished it in a few days. The prose is carefully and conscientiously crafted with a graceful literary style that treats complex concepts with clarity and brevity. Sometimes with one-word sentences. Oneword. And so funny! Whitehead’s process philosophy “must have St. Augustine revolving rapidly in his grave.” And discussing the pangs of moral conscience that follow from marking up library books–which is funny in itself–he writes,

God help the library books because apparently Darwin won’t. You’ll be sorry. Sleepless nights, wracked by conscience at that yellow highlighting of the Critique or Pure Reason. How could you destroy the joy of others as they set out, all pure and innocent and eager, into The Transcendental Analytic to find the Metaphysical Deduction has been marked up like a copy-editor’s proof.

Hilarious. If you ever tried to read Kant … well, it’s not a joyful experience. The pages of my old copy are brittle from long ago tears.

Ruse does assume his readers have some background in philosophy. He writes “better Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied” or “existence precedes essence” or “Popperian” without explanation. But this is not problematic. Such examples are rare and almost always self-explanatory. If not there’s always google.

A Brief Synopsis – With my commentary in [brackets.]

Ruse wants to know if human beings are justified in thinking themselves special. The answer to this question comes from science, specifically from evolutionary biology. Moreover, his discussion will lead to moral questions such as, what should we do and why should we do it? Again evolutionary biology provides the most important insights. I agree. We can’t talk intelligently about human nature or ethics without an understanding of our evolutionary past.

The first chapter distinguishes between a)religious; b)secular; and c)creationists views of human nature. It’s important to note that his small (c) creationists are NOT biblical literalists. Instead, they are those who think “human nature is … created not discovered.” They think that we are special because “we have the ability to make ourselves special.” [If we are indeed special because we can improve our nature then, as a transhumanist, I ask “why not follow this evolutionary thinking to its logical conclusion? Why not transcend our nature? Don’t we have a moral obligation to make ourselves more special?]

For Ruse, Sartre exemplifies small (c) creationism. Quoting Sartre,

God does not exist, yet there is still a being in whom existence precedes essence, a being which exists before being defined by any concept, and this being is man or, as Heidegger puts it, human reality. That means that man first exists, encounters himself and emerges in the world, to be defined afterwards. Thus, there is no human nature, since there is no God to conceive it. It is man who conceives himself, who propels himself towards existence …

[The transhumanism here is implicit. If we define ourselves, if we conceive ourselves, then let’s use every means available to do that. Remember that we call our human nature is not static, it simply refers to our current stage of evolutionary development.] Ruse argues then that it isn’t God or nature that makes us special—if indeed we are special—rather that is a judgment we make about ourselves. We are nothing more or less than what we have made of ourselves. [Agreed. So let’s make more of ourselves.]

There is a lot to say about the intervening chapters but let me outline the logic that leads to the book’s conclusions so as not to provide too many spoilers.

If science is the key to answering questions about our nature then “we must dig into the underlying metaphysical presumptions that people bring to their science.” This is the subject matter of the second chapter. Here he introduces the distinction between organicism and mechanism—the two metaphysical assumptions brought to science. Roughly speaking, some people think that the world is an organism and that humans have a natural value because they are the most special part of this world (or of the creation for the religious.) Others think that the world is a machine and that we must make our own value judgments, including judgments about ourselves.

Next, in Chapter 3, he turns to Darwinian evolutionary theory which explains human nature. [This should be obvious but many philosophers, particularly religious ones, use a 2,500-year-old version of human nature in their philosophy.] Chapters 4 & 5 evaluate Darwinian claims about human nature in light of the metaphysical assumptions discussed in Chapter 2. In Chapter 6 Ruse considers the question of progress, to see if organicism and mechanism reach different conclusions. In the last 2 chapters, he compares the views of organicism and mechanism in the moral realm.

The epilogue looks at the moral realm, “as seen through the lenses and demands of the three groups of the first chapter—the religious, the secular, the creationist?” Ruse defends small (c) creationism, what he calls Darwinian existentialism—we create our own values, we create our own meaning.

However, this does not imply naive moral relativism. For we are social, we are part of a group and our ancestors found rules of behavior that worked—we all do better if we all cooperate; we benefit from reciprocity. We get our morality from our evolved human nature along with cultural influences. There is no higher standard than that.

What then makes humans special? Ruse concludes,

As a Darwinian existentialist, I ask for no more than I have. As a Darwinian existentialist, I want no more than I have. I am so privileged to have had the gift of life and the abilities and the possibilities to make full use of it.

I am moved by Ruse’s humble gratitude for the chance to have lived, and in his case, to have lived well-lived. But he can do all this and take a final step. Let me explain.

E.O. Wilson wrote,

The human species can change its own nature. What will it choose? Will it remain the same, teetering on a jerrybuilt foundation of partly obsolete Ice-Age adaptations? Or will it press toward still higher intelligence and creativity …

Now consider Ruse’s creationism (c), standing on our own, looking within, Darwinian existentialism. I agree but with a major caveat. I do ask for more and I do want more. Not just for myself but for others. For all of us, I want more consciousness, more justice, more joy, more life.

I believe that Ruse’s evolutionary perspective, his emphasis on creating our own meaning and values leads naturally to transhumanism. If “it is having to stand on your own … that makes humans of great worth” then we really stand on our own, really create ourselves if we transcend our current nature. Why be content with our current nature? Why not direct evolution?

Yes, this is risky, but with no risk-free way to proceed, we either evolve or we will die. We know what we are, but we know not what we may become. Or, as Nietzsche put it “What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal…” Nietzsche wasn’t on board with all this “humans are so great stuff.” I’m not either. I’m no angel, just a modified monkey who was lucky to have great parents, a middle-class lifestyle, a good education, and a job where I received free exam copies of Michael Ruse books!

So transhumanism complements Ruse’s evolutionary vision. Once you adopt an evolutionary perspective, and Ruse is one of the world’s more ardent defenders of the truth of Darwinism, then you should look not just to the past and present but to the future. Ruse is a philosopher looking at human beings as they are now. His analysis is spot on. But taking an evolutionary perspective, I’m more interested in what we might become. What can we make of ourselves?

I do know this. If we survive and prosper, our descendants will come to resemble us about as much as we do the amino acids from which we sprang. Surely this is something for any evolutionist to ponder.

________________________________________________________________________

I’d like to thank Professor Ruse for writing his book. I’ve read many of his works over the years and have always enjoyed them. (I previously reviewed his A Meaning to Life.)

January 5, 2022

E.O. Wilson Has Died

[image error]

Edward O. Wilson, one of my intellectual heroes, died last week. As I said previously,

E. O. Wilson taught me that human behavior has biological roots; that nothing makes sense except in the light of evolution; that the biosphere is our only home; that most people would rather believe than know; that the evolutionary epic is the grandest narrative we will ever have; and that we must direct the course of our future evolution. He is both a great scientist and a man filled with a childlike wonder for the natural world.

And in my post, “4 More Memorable Books,” I wrote,

Late in my graduate school career, E.O. Wilson’s On Human Nature was assigned for a graduate seminar in evolutionary ethics. It is the only one of the eight books I’ve selected that was assigned for a class. Wilson wasted no time advancing his thesis,

On Human Nature was assigned for a graduate seminar in evolutionary ethics. It is the only one of the eight books I’ve selected that was assigned for a class. Wilson wasted no time advancing his thesis,

… if the brain is a machine of ten billion nerve cells and the mind can somehow be explained as the summed activity of a finite number of chemical and electrical reactions, boundaries limit the human prospect—we are biological and our souls cannot fly free. If humankind evolved by Darwinian natural selection, genetic chance and environmental necessity, not God, made the species … However much we embellish that stark conclusion with metaphor and imagery, it remains the philosophical legacy of the last century of scientific research … It is the essential first hypothesis for any serious consideration of the human condition.1

Yes, I knew all this before I read Wilson, but his prose cemented these ideas within me. Evolutionary biology is the key to understanding mind and behavior, and to understanding morality and religion as well. Life and culture are thoroughly and self-evidently biological. Yet most people reject these truths, choosing ignorance and self-deception instead. They mistakenly believe that they are fallen angels, not the modified monkeys they really are. But why can’t they accept the truth? Because, as Wilson says, most people “would rather believe than know. They would rather have the void as purpose … than be void of purpose.”2

Yet, I didn’t find Wilson’s lessons depressing. Science liberates by giving us self-knowledge, while simultaneously placing within us the hope “that the journey on which we are now embarked will be farther and better than the one just completed.”3 Wilson’s book taught me who we are, the dilemmas we face, and how we must choose our future path. He is right, the evolutionary idea is the greatest and truest one that humans have ever discovered.

I would like to thank Professor Wilson for his lifelong service to the noble cause of science and reason. And I would like to especially thank him for the deep and profound influence he has had on my intellectual development. He taught me so much.

For those interested, here are a few short essays I’ve previously written about Wilson.

Notes.

1. Edward O. Wilson, On Human Nature (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979) 1-2.

2. Wilson, On Human Nature, 170-171.

3. Wilson, On Human Nature, 209.

January 2, 2022

“Why Not Let Life Become Extinct?”

[image error]

John Leslie (1940 – ) is currently Professor Emeritus at the University of Guelph, in Ontario, Canada. In his essay “Why Not Let Life Become Extinct?” he argues that we ought not to embrace the view that extinction would be best.

Some argue that it would not be sad or a pity if humans went extinct because: 1) there would be nobody left to be sad; or 2) life is so bad that extinction is preferable. Leslie maintains that this issue has practical implications since someone with power might decide that life is not worth it, and press the nuclear button (or bring about some other extinction scenario.) Fortunately, most do not reason this way, but if they do there is a paucity of philosophical arguments to dissuade them. Moreover, philosophers often advance arguments that we should improve the lives of the worst off and, since so many people live wretched lives, it is easy to see that a solution might entail killing a lot of people.

But what of letting all life go extinct? Some philosophers argue that we have no duty to prevent this, that even if life is good we have no duty to propagate it, or if someone is about to lose their life we have no obligation to save it. The principle behind such thinking is that though we ought not to hurt people, we have no duty to help them. Other lines of thinking may lead to similar conclusions. A utilitarian might argue that life should go extinct if it is sufficiently unhappy now or will be so in the future. Others argue that we have no duties to produce future people no matter how happy they might be, for the simple reason that these possible people cannot be deprived of anything, as they do not yet exist. Leslie counters that deciding whether to produce a situation should be influenced by what the situation will be like, by its consequences. If one is deciding whether to produce a certain future, the most relevant fact is whether that future will be good.

He now makes some concessions. First, it is morally good to want to make the lives of the worst-off better, but not if this entails destroying the entire human race. Second, actual people are not obligated to make all sacrifices for possible people, any more than you are obliged to give food to others when your own family is starving. Third, given overpopulation, we are not obligated to have children.

And since ethics is imprecise, we cannot be sure that we have duties to future generations. Still, the universe has value despite the evil it contains, leading Leslie to speculate that there might be an “ethical requirement that it exist…” In other words a thing’s nature, if it has intrinsic value, makes its existence ethically required. But how can the description of a thing’s nature lead to the prescription that it ought to exist? Leslie argues that we cannot derive that a thing should exist from a description of its nature. Perhaps it would be better if no life existed. But suppose we agree that life is intrinsically good, would we then have an obligation to perpetuate it? Leslie answers no. A thing’s intrinsic goodness only implies some obligation that it exists, since other ethical considerations might overrule that obligation. For instance, a moral person might think it better that life ended than have a world with so much suffering. The upshot of all this is that there are no knockdown arguments either way. Competent philosophers who argue that it is better for there to be no life probably are on equal footing with those who argue the opposite. Leslie continues: “Still, pause before joining such people.”

In the end, we cannot show conclusively that we should not let life become extinct because we can never go from saying that something is—even happiness or pleasure—to saying that something should be. And it is also not clear that maximizing happiness is the proper moral goal. Perhaps instead we should try to prevent misery—which may entail allowing life to go extinct. Philosophers do not generally advocate such a position, but their reluctance to do so suggests that they are willing to tolerate the suffering of some for the happiness of others.

Summary – There are strong arguments for letting life go extinct, although Leslie suggests we generally reject them because life has intrinsic goodness.

_________________________________________________________________

John Leslie, “Why Not Let Life Become Extinct?” (1983) in Life, death, and meaning, ed. David Benatar (Lanham, MD.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), 128.

Leslie, “Why Not Let Life Become Extinct?” 130.

December 31, 2021

The Philosophy of Nikos Kazantzakis

[image error]

“In my thirty-three years by his side, I cannot remember ever being ashamed by a single bad action on his part. He was honest, without guile, innocent, infinitely sweet toward others, fierce only toward himself.” ~ Elina Kazantzakis

I have previously expressed my affinity for the thought of the Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis (1883 – 1957). I would now like to highlight a few more of his salient ideas. I begin with a disclaimer. Kazantzakis was a voluminous author who wrote a 33,333 line poem, The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, six travel books, eight plays, twelve novels, and dozens of essays and letters. So no summary does justice to the complexity of his thought. He was a giant of modern Greek literature; nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in nine different years.[2] He is best known to the English-speaking world for his novels, Zorba the Greek[image error] and The Last Temptation of Christ[image error], as both were adapted to the cinema.

[image error][image error] [image error]

Report to Greco

In the prologue to Nikos Kazantzakis’ autobiography, Report to Greco, he writes that there are three kinds of souls: One wants to work; one doesn’t want to work too much, and one finds solace in being overworked. Kazantzakis thought of himself as the third type of soul.

Nikos Kazantzakis was born in 1883 in Heraklion, Greece into a peasant family surrounded by fishermen, farmers, and shepherds. Of his parents he said:

Both of my parents circulate in my blood, the one fierce, hard, and morose, the other tender, kind, and saintly. I have carried them all my days; neither has died … My lifelong effort is to reconcile them so that the one may give me his strength, the other her tenderness; to make the discord between them, which breaks out incessantly within me, turn to harmony inside their son’s heart.

As a child, he was enrolled in a school run by French Catholics where he found religious history fascinating with its fairy tales of “serpents who talked, floods and rainbows, thefts and murders. Brother killed brother, father wanted to slaughter his only son, God intervened every two minutes and did His share of killing, people crossed the sea without wetting their feet.” Religion would become a lifelong object of his thinking.

After completing his secondary education, he sailed to Athens where he studied law for four years. He recalled the time with sadness: “My heart breaks when I bring to mind those years I spent as a university student in Athens. Though I looked, I saw nothing … this was not my road …” After he returned home he wandered the countryside, alone except for his books and notebooks. He had begun to feel the pull of writing: “Here is my road, here is duty.” He would never look back.

Indignation had overcome me in those early years. I remember that I could not bear the pyrotechnics of human existence: how life ignited for an instant, burst in the air in a myriad of color flares, then all at once vanished. Who ignited it? Who gave it such fascination and beauty, then suddenly, pitilessly, snuffed it out? “No,” I shouted, “I will not accept this, will not subscribe; I shall find some way to keep life from expiring.”

His Philosophy

In his early years Kazantzakis was moved by Nietzsche’s Dionysian (emotional and instinctive) vision of humans shaping themselves into the Superman, and with Bergson’s Apollonian (rational and logical) idea of the elan vital. From Nietzsche, he learned that by sheer force of will, humans can be free as long as they proceed without fear or hope of reward. From Bergson, under whom he studied in Paris, he came to believe that a vital evolutionary life force molds matter, potentially creating higher forms of life. Putting these ideas together, Kazantzakis declared that we find meaning in life by struggling against universal entropy, an idea he connected with God. For Kazantzakis, the word god referred to “the anti-entropic life-force that organizes elemental matter into systems that can manifest ever more subtle and advanced forms of beings and consciousness.”[i]The meaning of our lives is to find our place in the chain that links us with these undreamt of forms of life.

We all ascend together, swept up by a mysterious and invisible urge. Where are we going? No one knows. Don’t ask, mount higher! Perhaps we are going nowhere, perhaps there is no one to pay us the rewarding wages of our lives. So much the better! For thus may we conquer the last, the greatest of all temptations—that of Hope. We fight because that is how we want it … We sing even though we know that no ear exists to hear us; we toil though there is no employer to pay us our wages when night falls. [ii]

In his search for his god—or what I would call his search for meaning—he ends not as a believer, prophet or saint, he arrives nowhere. Kazantzakis thought of the story of his life as an adventure of mind, spirit, and body—an odyssey or ascent—hence his attraction to Homer. In, The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel, Odysseus gathers his followers, builds a boat, and sails away on a final journey, eventually dying in the Antarctic. According to Kazantzakis, Odysseus doesn’t find what he’s seeking, and he doesn’t save his soul—but it doesn’t matter. Through the search itself, he is ennobled—the meaning of his life is found in the search. In the end, his Odysseus cries out, “My soul, your voyages have been your native land.”[iii]

In the prologue of Report to Greco[image error], Kazantzakis claims that we need to go beyond both hope and despair. Both expectation of paradise and fear of hell prevent us from focusing on what is in front of us, our heart’s true homeland … the search for meaning itself. We ought to be warriors who struggle bravely to create meaning without expecting anything in return. Unafraid of the abyss, we should face it bravely and run toward it. Ultimately we find joy, in the face of tragedy, by taking full responsibility for our lives. Life is a struggle, and if in the end, it judges us we should bravely reply as Kazantzakis did:

General, the battle draws to a close and I make my report. This is where and how I fought. I fell wounded, lost heart, but did not desert. Though my teeth clattered from fear, I bound my forehead tightly with a red handkerchief to hide the blood, and ran to the assault.”[iv]

Surely that is as courageous a sentiment in response to the ordeal of human life as has been offered in world literature. It is a bold rejoinder to the awareness of the inevitable decline of our minds and bodies, as well as to the existential agonies that permeate life. It finds the meaning of life in our actions, our struggles, our battles, our roaming, our wandering, and our journeying. It appeals to nothing other than what we know and experience—and yet finds meaning and contentment there.

Kazantzakis was always controversial and misunderstood, his philosophy too ethereal for most readers. He was accused of atheism in 1939 by the Greek Orthodox Church, although he was never summoned to trial. They tried again in 1953, outraged by his depiction of Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ—a book subsequently placed on the Index of forbidden books by the Roman Catholic Church.

In the last decade of his life Kazantzakis prolific, producing eight books. A psychologist once told him that he possessed energy “quite beyond the normal.” In 1953 he developed leukemia, frantically throwing himself into his work, but wishing he had more time. “I feel like doing what Bergson says— going to the street corner and holding out my hand to start begging from passersby: ‘Alms, brothers! A quarter of an hour from each of you.’ Oh, for a little time, just enough to let me finish my work. Afterwards, let Charon come.” He continued to work and travel, but died in 1957 with his wife at his side.

Just outside the city walls of Heraklion Crete, one can visit Kazantzakis’ gravesite, located there as the Orthodox Church denied his being buried in a Christian cemetery. On the jagged, cracked, unpolished Cretan marble you will find no name to designate who lies there, no dates of birth or death, only an epitaph in Greek carved in the stone. It translates: “I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free.”

The gravesite of Kazantzakis.

____________________________________________________________________

[i] James Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 11th ed. (Belmont CA.: Wadsworth, 2012), 656

[ii] Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 656.

[iii] Christian, Philosophy: An Introduction to the Art of Wondering, 653.

[iv] Nikos Kazantzakis, Report to Greco (New York: Touchstone, 1975), 23

December 29, 2021

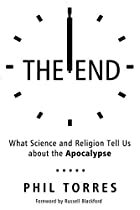

Science, Religion and the Apocalypse

The basic theme of Phil Torres’ book, The End: What Science and Religion Tell Us about the Apocalypse , is that new technologies threaten the survival of the entire human species. Moreover, belief in religious eschatologies, or end-time narratives, greatly exacerbate the problem. These superstitious, faith-based beliefs greatly increase the probability that our species will either annihilate itself or fail to anticipate various existential threats because, as technology becomes more powerful, the ability of religious fanatics to realize some of their apocalyptic visions increases. Our predicament then is that “neoteric technologies and archaic belief systems are colliding with potentially catastrophic consequences.” (18)

, is that new technologies threaten the survival of the entire human species. Moreover, belief in religious eschatologies, or end-time narratives, greatly exacerbate the problem. These superstitious, faith-based beliefs greatly increase the probability that our species will either annihilate itself or fail to anticipate various existential threats because, as technology becomes more powerful, the ability of religious fanatics to realize some of their apocalyptic visions increases. Our predicament then is that “neoteric technologies and archaic belief systems are colliding with potentially catastrophic consequences.” (18)

Now religious believers have been crying that the “end is near” for a long time. Most biblical scholars see Jesus as a failed apocalyptic prophet, and throughout history, many Christians have forecast that the end of the world was imminent. Eschatological beliefs play a large role in Islam as well, and many Muslims believe that Madhi will descend from heaven along with Jesus to usher in the end of the world. While such beliefs are silly, they are not irrelevant. When false beliefs influence us, they also can harm us.

Such considerations lead Torres to differentiate between religious and secular eschatology. Faith and revelation provide the epistemological foundation for supernatural eschatology, while reason, observation, and evidence underlie the epistemological foundation of worries about natural threats. It follows then that rational persons should take the latter threats seriously, but not the former. We should worry that asteroids, pathogens, nuclear war, artificial intelligence and the like may destroy, but not worry that Jesus or Allah will. But again believers in religious eschatologies are dangerous, especially if they utilize advanced technologies to usher in their view of the apocalypse.

Yet, despite the real possibility that we will destroy ourselves, Torres argues that we typically underestimate existential risks. We have survived thus far, we reason, so we’ll probably continue to do so. But this is mistaken. For all we know many intelligent civilizations didn’t survive the disruptions caused by their advancing technologies and superstitious religious apocalyptic visions. How we respond to this tension between secular and religious eschatologies will determine in large part whether we survive and flourish, or go extinct.

Such considerations lead Torres to claim: “This makes the topic of existential risks quite possibly the most important that one could study … everything we care about in the world, in this great experiment called civilization, depends on us preventing an existential catastrophe.” (26) Our descendants might live forever, traverse the universe, and become godlike. Or the universe might expand forever as cold, dark, and lifeless. Given these stakes, the study of existential risks is urgent, especially when you consider there are no second chances when it comes to existential catastrophe. What then are these naturalistic threats to our survival? Torres discusses them in turn.

Some are omnipresent, like the nuclear weapons on hair-trigger alert. Their use could cause nuclear winter and the starvation, disease, or extinction that might follow. Pandemics caused by viruses and bacteria pose another threat, as does bio-terror unleashed by deranged individuals or groups, as well as the simple errors caused by the application of biotechnology. Molecular manufacturing may bring abundance, but may be used for nefarious purposes too. Moreover, out-of-control nanobots could conceivably destroy the biosphere. Superintelligence is also a danger, as unfriendly, indifferent or even friendly AI might destroy us, either accidentally or on purpose. Furthermore, given that there is a chance that we now live in a simulation, it is possible that we will simply be turned off.

Our interaction with nature may imperil us too. More than 50% of vertebrates have gone extinct in the last fifty years, and we may also be on the verge of a catastrophic collapse of the ecosystem which leaves the planet uninhabitable. In addition, global warming poses an existential threat, as do supervolcanoes, comets, and asteroids.

One of the most interesting threats comes from what Torres calls monsters. These are risks caused by things that we cannot currently conceptualize. So there are unintended consequences of what we do or do not do, and there are natural phenomena that endanger us of which we are unaware. If we do survive for another hundred years, we will probably look back on the present time and realize there were extinction scenarios that we didn’t even think of. But even if we avoid extinction for eons of time, the universe itself seems destined for oblivion, unless our progeny can somehow stop such universal forces.

Torres turns next to the way that religious beliefs about the future negatively affect prudent actions in the present. The most prominent examples are Christian dispensationalist and Islamic eschatologies. Dispensationalism, a set of Evangelical Christian beliefs about the future, demands, for example, that the United States defend Israel unconditionally. It also dictates that Christians be generally antagonistic toward Palestinians and other Arabs. Islamic eschatologies also influence both people and governments while clashing with Christian eschatologies. The problem is that these superstitious religious eschatologies both increase violence between groups now, as well as the probability of a secular apocalypse in the near future.

The perils posed by belief in religious eschatologies are difficult to overstate. Rather than believing that maximizing happiness is the point of life, as secularists tend to do, the religious tend to believe that doing some God’s will is the purpose of life. (Naturally, they believe that they have access to the divine mind with their own small ape-like brains!)The problem is those religious beliefs are extraordinarily influential in people’s lives. And consider that by 2050 about 60% of the world’s population will be either Christian or Muslim.

What do the religious beliefs about the fate of the universe? More than 40% of Americans believe that Jesus will probably or definitely return during their lifetime—almost 60% of Evangelical Christians of Americans believe this—while more than 60% of American Evangelicals believe in the Rapture. Moreover, many influential American politicians hold such beliefs. (To take one example, consider how religious conservatives in the American government feel compelled to deny global climate change.) In addition, almost half of all Muslims believe the return of Mahdi will occur during their lifetimes, and nearly the same amount expect to be alive to see Jesus return. Remember again that billions of people are either Christians or Muslims. So even if only a small percentage of them are fanatics determined to inflict catastrophic harm, there would still be millions of such people. And they would be armed with advanced technologies.

Given these many hazards we now face, are there good reasons to believe we can survive? While noted thinkers Steven Pinker and Michael Shermer are optimistic about the future based on past moral progress, Torres is less sanguine. The number of extinction scenarios has increased as our technology has advanced, so inferences from the past about our future survival aren’t helpful. This leads Torres to reject what he calls the “bottleneck hypothesis,” the idea that if we can squeeze through our current situation we’ll be fine. Instead, he accepts the “parallel growth hypothesis,” the notion that future technologies will bring about so many new ways to annihilate ourselves that our extinction is practically certain.

Still, despite his misgivings, Torres offers multiple ways we might increase the chances of surviving. The most promising demands that we evolve into a posthuman species. In other words, to have descendants at all humans as we know them must go extinct. And, as Torres notes, this evolutionary transition will have to happen soon before we annihilate ourselves.

Other methods to increase our survivability include: 1) creating superintelligence; 2) colonizing space; 3) staggering technological development; 4)improving education, especially by teaching the critical thinking skills that undermine religious belief; 5) defeating the anti-intellectualism that closes minds; 6) better utilizing female minds; 7) supporting organizations that focus on existential risks; 8) reducing your environmental impact; 9) getting overpopulation under control; and 10) full-fledge revolt if all else fails.

There is little to find fault within Torres’ analysis. The only thing I might say is that, while I agree that religion is generally as harmful as it is untrue, the secular apocalypse can arrive independent of any belief in a religious eschatology. We might use nuclear or chemical weapons to kill each other because we are greedy, aggressive, racist, ideological, or territorial; we might release pathogens or artificial intelligence that inadvertently annihilate us all; or asteroids or supervolcanoes could destroy us because we aren’t intelligent enough to stop them. Even without religious belief, any of this could happen.

So consideration of biological, psychological, social, cultural, and economic factors is also important in understanding how we might avoid oblivion. Torres would no doubt agree. But his proposed solution for avoiding the apocalypse—reason, observation, and science over faith, revelation, and religion—works best against the threat posed to our survival by religious beliefs. However, it is less clear how this suggestion helps us avoid the challenges that ensue from human biology and psychology. Even if we augment our intelligence or even become omniscient, this would not be sufficient to assure our survival. I think we would also need to augment our moral faculties to enhance our chances of survival. So becoming posthuman—putting an end to human nature before it puts an end to us—gives us the best chance of there being any future for consciousness. However such recommendations obviously come with risks.

In conclusion, let me say that Torres’ book offers a fascinating study of the many real threats to our existence, provides multiple insights as to how we might avoid extinction, and is carefully and conscientiously crafted. Perhaps what strikes me most about Torres’ book is how deeply it expresses his concern for the fate of conscious life, as well as his awareness of how tenuous consciousness is in the vast immensity of time and space. The author obviously loves life and hates to see ignorance and superstition imperil it. He implores us to remember how the little light of consciousness that brightens this planet can be quickly extinguished—and that we will only be saved by reason and science. This is Torres’ central message, which he states most eloquently in his conclusion:

While science, philosophy, art, culture, music, literature, poetry, fashion, sports, and all the other objects of civilization make life worth living, avoiding an existential catastrophe makes it possible. This makes eschatology, with its two interacting branches, the most important subject that one could study. Without an understanding of what the risks are before us, without an understanding of how the clash of eschatologies has shaped the course of world history, we will be impotent to defend against the threat of (self-)annihilation … Our situation has always been precarious, but it’s never been as precarious as it is today. If we want our children to have the opportunity of living the Good Life, or even existing at all, it’s essential that we learn to favor evidence over faith, observation over revelation, and science over religion as we venture into a dangerously wonderful future. (249)

December 22, 2021

Simon Critchley’s: Very Little … Almost Nothing

[image error]

Simon Critchley (1960 – ) was born in England and received his Ph.D. from the University of Essex in 1988. He is series moderator and contributor to “The Stone,” a philosophy column in The New York Times. He is also currently chair and professor of philosophy at The New School for Social Research in New York City.

[image error]In his book, Very Little … Almost Nothing: Death, Philosophy and Literature, Critchley discusses various responses to nihilism. Responses include those who: a) refuse to see the problem, like religious fundamentalists who don’t understand modernity; b) are indifferent to the problem, which they see as the concern of bourgeoisie intellectuals; c) passively accept nihilism, knowing that nothing they do matters; d) actively revolt against nihilism in the hope that they might mitigate the condition.[i]

[image error]In his book, Very Little … Almost Nothing: Death, Philosophy and Literature, Critchley discusses various responses to nihilism. Responses include those who: a) refuse to see the problem, like religious fundamentalists who don’t understand modernity; b) are indifferent to the problem, which they see as the concern of bourgeoisie intellectuals; c) passively accept nihilism, knowing that nothing they do matters; d) actively revolt against nihilism in the hope that they might mitigate the condition.[i]

But Critchley rejects all views that try to overcome nihilism—enterprises that find redemption in philosophy, religion, science, politics, or art—in favor of a response that embraces or affirms nihilism. For Critchley, the question of meaning is one of finding meaning in human finitude, since all answers to the contrary are empty. This leads him to the surprising idea that “the ultimate meaning of human finitude is that we cannot find meaningful fulfillment for the finite.”[ii]But if one cannot find meaning in finitude, why not just passively accept nihilism?

Critchley replies that we should do more than merely accept nihilism; we must affirm “meaninglessness as an achievement, as a task or quest … as the achievement of the ordinary or everyday without the rose-tinted spectacles of any narrative of redemption.”[iii]In this way we don’t evade the problem of nihilism but truly confront it. As Critchley puts it:

The world is all too easily stuffed with meaning and we risk suffocating under the combined weight of competing narratives of redemption—whether religious, socio-economic, scientific, technological, political, aesthetic or philosophical—and hence miss the problem of nihilism in our manic desire to overcome it.[iv]

For models of what he means Critchley turns to playwright Samuel Beckett whose work gives us “a radical de-creation of these salvific narratives, an approach to meaninglessness as the achievement of the ordinary, a redemption from redemption.”[v] Salvation narratives are empty talk which cause trouble; better to be silent as Pascal suggested: “All man’s miseries derive from not being able to sit quietly in a room alone.” What then is left after we reject the fables of salvation? As his title suggests; very little … almost nothing. But all is not lost; we can know the happiness derived from ordinary things.

Critchley finds a similar insight in what the poet Wallace Stevens called “the plain sense of things.”[vi] In Stevens’ poem, “The Emperor of Ice Cream,” the setting is a funeral service. In one room we find merriment and ice cream, in another a corpse. The ice cream represents the appetites, the powerful desire for physical things; the corpse represents death. The former is better than the latter, and that this is all we can say about life and death. The animal life is the best there is and better than death—the ordinary is the most extraordinary.

For another example, Critchley considers Thornton Wilder’s famous play “Our Town,” which exalts the living and dying of ordinary people, as well as the wonder of ordinary things. In the play, young Emily Gibbs has died in childbirth and awakens in an afterlife, where she is granted her wish to go back to the world for a day. But when she goes back she cannot stand it; people on earth ignore the beauty which surrounds them. As she leaves she says goodbye to all the ordinary things of the world: “to clocks ticking, to food and coffee, new ironed dresses and hot baths, and to sleeping and waking up.”[vii] It is tragic that while living we miss the beauty of ordinary things. Emily is dismayed but we are enlightened—we ought to appreciate and affirm the extraordinary ordinary. Perhaps that is the best response to nihilism—to be edified by it, to find meaning in meaninglessness, to realize we can find happiness in spite of nihilism.

___________________________________________________________________

[i] Simon Critchley, Very Little … Almost Nothing (New York: Routledge, 2004), 12-13.

[ii] Critchley, Very Little … Almost Nothing, 31.

[iii] Critchley, Very Little … Almost Nothing, 32.

[iv] Critchley, Very Little … Almost Nothing, 32.

[v] Critchley, Very Little … Almost Nothing, 32.

[vi] Critchley, Very Little … Almost Nothing, 118.

[vii] Thornton Wilder, Our Town (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1938), 82.

December 20, 2021

Is Unsolicited Advice Indistinguishable from Criticism?

[image error]The good advice (original title: Le bon conseil), by Jean-Baptiste Madou.

Unsolicited Advice as Criticism – Suppose I say: “You should move to Florida!” or “You should quit your job!” or “You eat too much!” or “You hang out with bad people!” In all these case there is implicit criticism. Of where you live or work; or of how much you eat or who you hang out with.

Suppose I put the above in question form: “Why don’t you think about moving to Florida?” or “Why don’t you consider eating less?” This may be a little better, a question rather than a command strikes a different tone, but still, the criticism is implicit if unsolicited. I must think there is something bad about where you live or what you eat.

Now does the intent of the adviser matter? I could advise you to move to Florida because then I won’t have to see you; or I could advise you to quit your job so I can have it. Similarly, I might advise you to stop eating so much because I don’t like to be around fat people; or I might advise you to not have certain friends because I want them. In these cases, I am not criticizing but trying to manipulate you. In fact, what I offer is not even advice in the typical sense of recommending some prudent action.

Unsolicited Advice that is not Criticism – Now suppose the situation is the typical one. I want to share with you some thoughts that might help you. I honestly believe you will live better if you exercise more and eat better, or I think you should quit your job because you have plenty of money and your work causes you a lot of stress; or I think you should not quit your job because it offers more money, autonomy and the possibility of doing more meaningful work than other jobs in the economy.

Of course, if such advice was solicited there is no problem. You ask and I answer the best I can. But suppose you don’t ask? I see you eating poorly, not exercising, contemplating quitting your job, or taking on another one. Do I have any obligation to share my opinion with you? And if I do is this criticism? I think I do have an obligation to share my opinion with you and this is not necessarily criticism, although it could be.

Unsolicited Advice that is Obligatory and Not Criticism– Suppose I don’t tell you what I think and you change your diet or quit your job and it doesn’t work out well. In that case, you might legitimately ask: “why didn’t you tell me your opinion?” or “did you just pretend to agree with me and not give me honest advice?” In each case your point is well-taken. If I saw you about to walk across the country without supplies or into the street without looking, I’m obligated to forewarn you with or without your solicitation. And the same with some radical change in your diet or work or childcare plans.

Naturally, I must respect your autonomy though. You might say “I want to walk in the street and don’t care about looking because I don’t care if I live or die.” Or you might say “Yes I’ll have less money if I quit my job but I’ll have enough and a lot more free time which is what I prefer.” In such cases, I may not agree with you but at least I have discharged my obligation to warn you or give you something to think about. So I am not criticizing your walking in the street or quitting your job. I’m just warning you. Unsolicited advice is not always criticism.

And the primary reason (or at least it should be the primary reason) I want to offer advice is that I care about you. I may have very good reasons to think you are overlooking something about your new diet or cross-country walk or job choice. You might think, for example, that you are allergic to gluten even though very few people are. Or you might be following the latest diet fad—no fat, no carbs, gluten-free—and I may have good reasons to think such a course isn’t prudent. When I give you advice like: “we’ll nutrition science is relatively new and imprecise so I wouldn’t be too quick to avoid all carbs from your diet,” I don’t think this is criticism. I could also add that I’m glad you are interested in nutrition and that you take it seriously but here is my opinion. And the same with the other situations. It is all well and good to quit your job for something better but I may be obligated to remind you that humans are bad at predicting their own happiness or that jobs may be very hard to come by in the future.

Now it’s true that I think you are overlooking something in all of these cases but this is not the same as criticizing you. I am sharing my thoughts with you and if you take this as criticism this says more about your emotional response than my intent. Let’s say that you’ve announced: “I only eat the diet of paleolithic man!” If you say that I have every right and even an obligation to say: “That’s fine but experts don’t even know what that diet was much less whether its good for you. Thus my advice is that you investigate this further.” This is advice but it is not criticism.

Consider another example. You tell me you are quitting a well-paying job and I say well maybe you shouldn’t. This is just expressing a thought at this point. Now suppose you say I’m quitting because I’m stressed and have plenty of money to live well without the high paying job. Now you have given me a good reason and you have not solicited my advice. At this point, I go home and think about what you said. I then may say: “My advice is that you quit because it sounds like you are really stressed.” Or I might say: “My advice is that you not quit because you’ll be more stressed without the money.” Or if you say “I’ll be happier at home every day rather than working.” I have the obligation to say “maybe but we are bad at predicting our happiness and people, in general, are happier when they are working than when they are not.” In all these cases I am giving you advice but not criticizing you, at most I am disagreeing with you. In fact, I may applaud you for thinking so seriously and conscientiously about the issue.

This raises the question of whether disagreeing is criticism. And the answer is that sometimes it is and sometimes it isn’t. Of course, some people only want their views confirmed so they’ll probably consider any advice to be criticism. But if they are concerned with hearing other views they shouldn’t necessarily consider unsolicited advice criticism.

In the end, I think it comes down in large part to the source of the advice. If it comes from persons you know who have your interest at heart, persons who love and care about you, such advice should be taken seriously, although not necessarily followed. Still, we often don’t follow others’ good advice to our detriment.

December 15, 2021

Why Do People Fear Immortality?

[image error]The Fountain of Eternal Life in Cleveland, Ohio.

Anyone who reads this blog knows that I think death should be optional. Yet I always encounter resistance when introducing this idea to others. Why is that? There are many reasons. For some, the idea that we should choose whether to live or die contradicts religious beliefs or seems impossible. For others, death is thought to be natural or what gives life meaning. And fiction often portrays being immortal as bad because it:

1) will be boring.

2) will leave you trapped, unable to die if you so choose.

3) will involve a loss of your humanity.

4) will involve hurting others in order to attain it.

5) will destroy the environment.

6) will sever our connection with the natural process of dying.

My guess is that negative views of the future are more exciting, selling more books and movie tickets than descriptions of utopias. But think of it this way. About ten generations ago the average life expectancy in most of the world was about thirty years. If someone told you then that they could triple that lifespan, would you voice the above concerns? I doubt it. Some people will be bad or bored or destructive because they live longer, Some are like that now. But for others with age comes more understanding, kindness, and wisdom. Yes, there are bored, horrific people in the world, but that is not connected with how long they live. Some people are just horrible.

Now suppose we tripled the lifespan again? Say an average healthy lifespan becomes 250 years. What would change? I can’t say for sure but I don’t think life would necessarily get worse. In fact, knowing our lives would be longer might force us to better cooperate with others and preserve the environment. If we are going to be alive when the ecosystem is ruined, we might be more likely to care for it.

Of course, if we had the option to live forever that would be different. That would create different questions some of which I’ve tried to answer previously. So let’s continue to increase our lifespans and see what happens.

Note. – I have answered a common objection that increased longevity will result in overpopulation here and here.

December 13, 2021

Anxiety and Depression from a Philosophical Viewpoint

Consider these two questions: 1) Are you responsible for being depressed or anxious? And 2) Should you feel guilty or ashamed of being depressed or anxious? Let’s consider the first question.

Here are four possibilities regarding your responsibility for being depressed:

1) You’re not free, and thus you are not responsible for being depressed;

2) You’re free, and thus you are responsible for being depressed;

3) You’re not free, but you are still responsible for being depressed;

4) You’re free, but you are not responsible for being depressed.

Consider the benefits and costs of each option:

The benefit of adopting #1 is that you don’t feel responsible for your situation; the cost is that you don’t feel free to change your situation.The benefit of #2 is that you do feel free to change your situation; the cost is that you feel responsible for your situation.#3 only has costs; you don’t feel free to change your situation, and you do hold yourself responsible for your situation.#4 only has benefits; you feel free to change your situation, and you don’t feel responsible for your situation.From a cost/benefit analysis, you should choose #4. Why don’t people do this? Probably because they don’t think #4 makes sense. Most people think that either #1 or #2 is true. But #3 and #4 are possibilities too. We might live in a determined world where people should still be held responsible (#3). Our mental states might be determined, but we are responsible for taking drugs or going to counseling to change those states. Or we might live in a world in which free will exists and yet people shouldn’t be held responsible (#4). We might be free to choose our actions and mental states, but not be responsible for them because determinism is very strong. (For more on free will go here and here and here.)

I’m don’t know which option best represents the state of the world. So we can’t definitely answer the question, “Am I responsible for being depressed or anxious?” But what we can say is that you might as well believe #4. To do this just accept that the past is determined, it is closed—you can’t affect it. But the future is not determined, it is open—you can affect it. (These claims could be wrong if backward causation is possible, or if fatalism is true. But almost no professional philosophers hold such views.) So it is easy to believe that we are free but not responsible.

Now consider the second question: Should you feel guilty for being depressed or anxious? Here an insight from Stoicism is invaluable—we can’t change the way some things are, but we can change our view of those things. Guilt and shame are attitudes toward reality that we can reject. So just think, “I will not feel guilt or shame.” Of course, we can choose shame and guilt, and if we do we shouldn’t feel guilty about that either. But we can choose not to do this too. We can say, to hell with guilt! So go ahead and say it. To hell with guilt! Remember, guilt is something that other people or organizations use so that they can control and manipulate you. Instead, control your view of things.

Now suppose you try to change your attitude, but a week or a month or a year later you still feel guilty about being depressed. I say keep trying, but don’t feel guilty about feeling guilty. Remember, you’re only free, if at all, regarding your actions in the present! And the present recedes into the past instantaneously. So just keep telling yourself: “right now I’m free to try to reject guilt, and even if I’m not successful I won’t feel guilty.”

But don’t try too hard either. Things take time, patience is a virtue. Relax, accept yourself, and let the guilt slowly recede. Remember that everything changes, and you will too. Go with the flow, change with the universe, and don’t fight too hard. Flow as peacefully as possible down the river of life.

In other words, don’t forget the Taoist concept of Wu Wei. Wu Wei literally means “without action”, “without effort”, or “without control.” It also means “action without action” “effortless doing” or “action that does not involve struggle or excessive effort.” This doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t act or that the will is bad, but that we should place our will and actions in harmony with nature. And sometimes nature will take its time to cure our ailments. Sometimes we just have to wait for things to pass. And, for better or worse, all things will pass.

December 9, 2021

“The Far Side of Despair” – Hazel Barnes

Hazel Barnes (1915-2008) was a longtime professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado at Boulder. She played a major role in introducing French existentialism to the English-speaking world through her translations and scholarship.

In her 1967 essay, “The Far Side of Despair,” Barnes asks why people assume that a lack of meaning or a grand purpose for the universe is bad. She argues that individuals project meaning onto a meaningless universe because of a desire for immortality, and a desire to share in the eternal goodness of the gods and their reality. The positive side to these beliefs is that it follows from them that what we do really matters, and a heaven awaits those who act correctly. The negative side is that there is a hell which corresponds to this promise of heaven. Of course, not all views of higher meaning depend on the idea of personal immortality—Aristotelianism and Hebraism do not—but most views of the meaningful life do suggest there is some proper place for humankind in the world.

Existentialism rejects all pronouncements of meaning. “Humanistic existentialism finds no divine presence, no ingrained higher meaning, no reassuring absolute.” Still, it is a fallacy to draw the inference that my life is not worth living from the fact that the universe has no meaning. Our lives may have intrinsic value both to ourselves and to others, although the universe does not care about us. In this context, Barnes quotes Merleau-Ponty: “Life makes no sense, but it is ours to make sense of.” And Sartre argues: “To say that we invent values means nothing except this: life has no meaning a priori. Before you live it, life is nothing, but it is for you to give it a meaning. Value is nothing other than this meaning which you choose.”

To contrast traditional views of meaning with existentialist ones, Barnes compares life to a blank game board with pieces but no instructions. Theological, rational, and nihilistic views all suggest that unless we can discover the correct pattern of the board and the correct instructions or rules, there is no reason to play the game. In contrast, existentialists maintain that though there is no pre-existing pattern imprinted on the board and no set of rules provided, we are left free to create our own game with its own patterns and rules. There is no objective truth about how to construct the game or live a life, but if the individual who constructs a life finds value in the creating, making, and living of a life then it has been worthwhile. Creating our own lives and values gives us satisfaction, elicits the approval of others, and may make it easier for others to live satisfying lives.

Still, for many this is not enough; they want some eternal, archetypical measurement for their lives. Barnes acknowledges that life is harder without belief in such things, but wonders if the price we would pay for this ultimate authority is too high. Given such an authority, humans would be measured and confined by non-human standards. We would be like slaves or children, whose choices are prescribed for them. Humans “in the theological framework of the medieval man-centered universe has only the dignity of the child, who must regulate his life by the rules laid down by adults. The human adventure becomes a conducted tour … The time has come for man to leave his parents and to live in his own right by his own judgments.”

Another problem for many with creating your own meaning is the implied subjectivity of value. How do we understand that what some people find meaningful others think deplorable? Barnes responds that she welcomes the fact that we possess the freedom to create our own values and live uniquely, it is part of growing up.

A final difficulty manifests itself when we contemplate the future. What difference will it make in the end whether I live one kind of life rather than another? What is the point of anything if there is no destination, no teleology? Barnes counters: “If there is an absolute negative quality in the absence of what will not be, then there is a corresponding positive value in what will have been.” In other words if nothingness is bad, it is so only because some existing things were good, and “The addition of positive moments does not add up to zero even if the time arrives when nothing more is added to the series.”

Barnes rejects the view that human life is worthless and meaningless just because it is not connected to a non-human transcendent authority. We are right to rebel against the fact that our lives must end, but we continue to exist after death in a sense because:

We live in a human world where multitudes of other consciousnesses are ceaselessly imposing their meaning upon [the external world]…and confronting the projects which I have introduced. It is in the future of these intermeshed human activities that I most fully transcend myself. In so far as “I” have carved out my being in this human world, “I” go on existing in its future.

Summary – We must grow up and create meaning for ourselves, rather than imagining some outside agency can do this. And through our projects, we have a kind of immortality.

_____________________________________________________________________

Hazel Barnes, “The Far Side of Despair,” in The Meaning of Life, ed. E.D. Klemke (Oxford University Press, 2000), 162.

Barnes, “The Far Side of Despair,” 162.

Barnes, “The Far Side of Despair,” 162.

Barnes, “The Far Side of Despair,” 162.

Barnes, “The Far Side of Despair,” 165.

Barnes, “The Far Side of Despair,” 165.

Barnes, “The Far Side of Despair,” 166.