John G. Messerly's Blog, page 32

November 12, 2021

More Great Essays

[image error]

Here are some very recent essays that I recommend. I intended to write a blog post summarizing them but simply don’t have the time. Perhaps my readers will find one or more to be especially mind-opening.

“The Meaning of Life in a World Without Work” – The Guardian

“Why You Should Believe in the Digital Afterlife” – The Atlantic

“Menace, as a Political Tool, Enters the Republican Mainstream” – The New York Times

“But What Would The End of Humanity Mean for Me?” The Atlantic

“Can Our Minds Live Forever?” – Scientific American

“Yuval Noah Harari Believes This Simple Story Can Save the Planet” – The New York Times

“Eight Rules of The School of Life” – The School of Life

“Climate Change Has Exposed the Decline of the American Empire” – The Nation

“How Will Our Species Survive in an Ever-Expanding Universe?” – Scientific American

“What if Everything You Learned About Human History Is Wrong?” – The New York Times

“Is Goodness Natural” – Aeon Magazine

“Why I Am Not a Libertarian” – The Weekly Sift

“Why philosophy needs myth” – Aeon Magazine

“Neuroscientist explains how fanatical Trump followers could lead us to societal collapse:” – Salon

“I Survived 18 Years in Solitary Confinement: The harrowing injustice I suffered as a boy should never happen to another child in this country.” – The New York Times

“That Luck Matters More Than Talent: A Strong Rationale for UBI” – Richard Carrier

“Automation and Utopia: Human Flourishing in a World Without Work” – John Danaher

“Can Artificial Intelligence Predict Religious Violence” – The Atlantic

“Why Simplicity Works” – Aeon Magazine

“Religious Freedom” means Christian Passive-Aggressive Domination” – The Weekly Sift

“Questioning the Hype About Artificial Intelligence” – The Atlantic

November 10, 2021

Children and Happiness

[image error]

I recently read “What Becoming a Parent Really Does to Your Happiness” in The Atlantic. Research has found that having children reduces the quality of life but the full truth about parenthood, happiness, and meaning in life is more complicated.

To understand these complications consider the common claim among philosophers that meaning isn’t the same thing as happiness. We can imagine someone being happy in many ways that don’t seem meaningful—collecting coins, copying the phonebook, being drunk most of the time, torturing children, hooked up to a pleasure machine, etc. We can also imagine meaningful lives that aren’t happy—an unhappy scientist who makes important discoveries, doing your duty working in the soup kitchen but hating the work, etc.

So perhaps it is the case that parenting is more meaningful than happy. Or, for another way to understand the complicated relationship between meaning and happiness ponder the following quote from my meaning of life summary which I think largely captures the authors of the article argument,

However, a meaningful life isn’t necessarily devoid of all obstacles for many meaningful projects—developing our talents, educating our minds, raising our children—involve disappointment. I’m not implying that suffering is good or desirable simply that it often accompanies our attempt to live meaningfully.There is obviously a lot to say here but for another perspective think about how Viktor Frankl found meaning, as far as it was possible, in concentration camps,Ultimately, we are not subject to the conditions that confront us; rather, these conditions are subject to our decision … we must decide whether we will face up or give in, whether or not we will let ourselves be determined by the conditions.

Or to put it another way, here is Frankl again,

It did not really matter what we expected from life, but rather what life expected from us. We needed to stop asking about the meaning of life, and instead to think of ourselves as those who were being questioned by life—daily and hourly. Our answer must consist, not in talk and meditation, but in right action and in right conduct. Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual.

Now obviously the difficulties of parenting don’t compare with those of a concentration camp—the latter is exponentially more difficult than the former. The point again is just that it is at least possible to find meaning in situations that don’t necessarily make us happy.1

Another way to think about meaning and happiness is found in Nietzsche,

A person who becomes conscious of the responsibility they bear toward a human being who affectionately waits for them, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away their life. They know the “why” for their existence, and will be able to bear almost any “how”.

Now I know that someone like Schopenhauer would argue that it is simply “the will to live” that blindly drives us to act so as to ensure both our own and the species survival. Be that as it may, I still think meaning can be found, among other places, in our relationships with our fellow human beings. And if can’t be found there, where would it be found?

____________________________________________________________________

1. I have always doubted that I could find meaning in such dire circumstances. Reminds me of Epictetus’ idea that he was never freer than when on the rack. I could never believe that either.

November 5, 2021

Dr. Harvey Wiley: A True Hero

[image error]Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley (October 18, 1844 – June 30, 1930)

I recently watched “The Poison Squad,” an episode on PBS’ American Experience. It is the story of a time when Americans had no idea that toxic substances were in their foods and of how government chemist Dr. Harvey Wiley who, determined to banish dangerous substances from dinner tables, took on the powerful food manufacturers and their allies. Dr. Wiley was an American chemist who fought for the passage of the landmark Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and subsequently worked at the Good Housekeeping Institute

laboratories. He was also the first commissioner of the United States Food and Drug Administration. He was awarded the Elliott Cresson Medal of the Franklin Institute in 1910.

Here’s the story in brief. Just over a hundred years ago, milk contained water, chalk, and borax! Formaldyhide was in everything. (Yes, the chemical used to preserve dead bodies.) In fact, no chemical was too deadly and no process too cheap to taint food. Canned meat for example was virtually inedible. However, the corporations who profited from the system didn’t want any government oversight or regulation and they fought and slandered Dr. Wiley for his entire life.

Surely this all sounds familiar. Corporations killing people for profit—think tobacco and fossil fuels—and trying to destroy anyone who threatens their profits. (If only people knew more about history.) But Wiley persevered and fought diligently for all of us. He also had help from the woman’s movement—mothers who wanted their children to eat safe food. Needless to say, his work isn’t done; much of the food produced today is still very bad for you. It may kill you slowly, but at least it won’t kill you immediately.

What then is Dr. Wiley’s legacy? According to one historian, it is that “You can buy a gallon of milk at the grocery store and not die.” Now that’s a great legacy.

We are all indebted to Dr. Wiley and the woman who aided his movement. I would like to thank all of them and I give the episode my unequivocal recommendation. Dr. Wiley was a true hero.

November 3, 2021

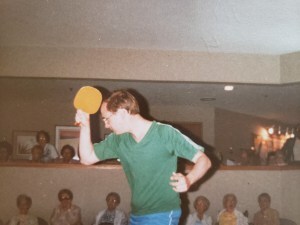

Playing Table Tennis

In the fall of 1968, I began watching members of the St. Louis table tennis club play in the auditorium of our church. I had never seen table tennis played at a high level so I was enthralled. One night my father asked one of the players, many times St. Louis champion Larry Chisholm, if he would hit a few with me. I had only played ping-pong a few times in my life but Larry told my dad I should enter an upcoming tournament. I actually won the boy’s Under 13 singles in that small tourney but—if I remember correctly—there were only 3 entries!

A few months later I bought my first inverted sponge racket and started to practice in my basement with my childhood friend Jim Foley and to play once a week with the St. Louis TT club. In the fall of 1969, I went to a tournament in Kansas City where I won my first 3 trophies—I was hooked. In early 1970 at the US Nationals in Detroit, I reached the quarterfinal of the boy’s Under 15s where I lost to Danny Seemiller—who would become perhaps the most legendary US table tennis player of all time. Shortly thereafter I achieved my first national ranking of #13 in the junior boys. In 1971 I finished 3rd in the St. Louis city championship in the men’s singles and won a number of boys under 18 events in major tournaments around the midwest.

In the fall of 1972, I won my first men’s singles tourney, and our 3 man St. Louis men’s team finished 9th in the national team championship out of over 100 teams. I played some close matches in that tourney with many of the top men’s players in the USA and Canada and had a win over the #19 ranked player in the country. (I also had a near win over George Braithwaite, a member of the US Men’s team that had played in China in 1971.) I was only 17 and now one of the top 5 or 6 junior players in the country.

Over the few months, I won a number of men’s singles events in tournaments in MO. and IL and was the men’s singles finalist in the Great Plains Open—the major regional tourney in the Midwest—in both 1973 & 1974. (In 1973 I lost to Richard Hicks and in 1974 to Housang Bozorgzadeh, both ranked in the top 10 in the USA and both members of the USA table tennis hall of fame.) I also played close matches with a number of other of the country’s other top 10 ranked players.

During this time I also played tournament matches against a number of players ranked in the top 20 in the world, including players from South Korea and China, but I was soundly beaten by all of them. I only averaged 11 or 12 points a game against world-class players. (At that time table tennis games were played to 21 points.) At that time I was ranked about #50 in men’s singles in the USA. (Bear in mind though that there were only about 10,000 serious tournament players then so this is nothing like being the 50th best tennis player, golfer, etc.)

In the summer of 1973, I was asked if I wanted to train with some of the best players in the country and I was also invited to do exhibitions at the halftime of the Harlem Globetrotters basketball games for the next year. But I decided to college instead. I played a little bit my first year of college and won all the tourneys in St. Louis but I was bored with table tennis because I couldn’t improve without moving to play with better players. I soon quit playing.

I did make a brief comeback in 1978, mostly because I had never flown in a plane, and I found out that the winners of regional tourneys of the Association of College Unions International were flown to Houston for the national college championships. I won my regional in a tournament in Kansas and got my plane ride but lost to the eventual winner in an early round. I did win the Missouri State Men’s Singles and Doubles titles in 1978 but that was basically the end of my brief career.

Again, I tell this story for my grandkids. Perhaps they will get a kick out of it. However, I want them to know being a philosopher was much more rewarding, fulfilling, and important than playing ping pong—duh! Still, I had fun climbing the table tennis ladder and you can learn things from sports. Most importantly, I made many good friends along the way—especially Jim Foley, Rich Berg, Rich Doza, George Hendry, Dan Dunay, Joe Windham, and Frank Mercz.

But sometimes I think my dad got the most joy from my playing. He built a trophy case in our family room to display my many trophies and he loved boasting about my skills. Shortly before he died I thanked him for helping me get into table tennis all those years ago and of my fond memories of battling—well they were pretty one-sided battles—with some of the world’s best players.

In the end, though I’m glad I chose my path. I think I am a good philosopher, friend, father, husband, and citizen of the world. So much more important than being a decent ping pong player. Still, we sometimes wonder about the lives we might have led had we made different choices in the garden of forking paths. Perhaps, if I had moved and played against better competition, I might have made the national team. Or perhaps had I followed through with an internship as a medical ethicist at the Cleveland Clinic in the mid-90s I would be much wealthier than I am now! Or perhaps …

For all of us, there are many lives we could have lived, but we only lead one. And so we should try to live that one well.

__________________________________________________________________________

Yes, that’s me in the picture above. I’m in my early 30s and my dad asked if I would do a table tennis exhibition in his retirement home with my friend George Hendry. What I remember most was that the table was on a carpet—a no-no in table tennis as the bounce becomes unpredictable—and the lighting consisted of a few lamps far away from the table—you could hardly see the ball. My dad was the mc. I hope he enjoyed it.

(I told this story for my grandchildren and for readers who might appreciate it.)

October 29, 2021

Critical Thinking

[image error]

In a recent post, I critique the often nonsensical idea of “doing your own research.” You know, the person who says “Those professional biologists have some ideas about biological evolution but I have my own opinions about that!” Anyway for those interested, here is a sampling of some of the things I’ve written on critical thinking.

The Basics of Critical Thinking Part 1: You Don’t Always Have A Right To Your Opinion

The Basics of Critical Thinking Part 2: Who Should I Believe?

The Basics of Critical Thinking Part 5: More Crimes Against Logic

October 26, 2021

Summary of “Longtermism” and “Existential Risk”

[image error]

Phil Torres recently published “The Dangerous Ideas of “Longtermism” and “Existential Risk” in Current Affairs. The essay’s thesis is that so-called rationalists have created a disturbing secular religion that appears to address humanity’s deepest problems but actually pursues the social preferences of elites. Here is a brief summary of the article. (I’ve published reviews of Torres’ past books here and here.)

Torres begins by noting that Skype co-founder Jaan Tallinn minimizes the risk of climate change. Why? Maybe he doesn’t think it will affect a wealthy person like himself. Perhaps. But most likely, Torres argues that a moral worldview called “longtermism” informs Tallin’s thinking.

Longtermism doesn’t just propose we care about future generations. Rather it insists that we should fulfill our potential which includes “replacing humanity with a superior “posthuman” species, colonizing the universe, and ultimately creating an unfathomably huge population of conscious beings who likely will live “inside high-resolution computer simulations.” Existential risks then are events that destroy this transhumanist future.

Furthermore, “longtermism” has become one of the main ideas promoted by the “Effective Altruism” (EA) movement. EA argues that altruism should not be driven by trying to feel good but rather by data showing what actually does good. For example, computer science research may help avoid an AI-generated disaster and ultimately bring about far more value than say, lifting a million people out of poverty today. (The utilitarian nature of EA is obvious.)

Now in this light consider climate change. It may cause great harm in the next few decades and centuries but if it is the very far future that matters then this near-term suffering pales in comparison to the potential good in the far future. As Nick Bostrom writes of the Holocaust or World Wars or the Black Death: “Tragic as such events are to the people immediately affected, in the big picture of things … even the worst of these catastrophes are mere ripples on the surface of the great sea of life.”

Now for longtermists this implies “that even the tiniest reductions in “existential risk” are morally equivalent to saving the lives of literally billions of living, breathing, actual people.” Torres finds this morally reprehensible.

To make this concrete, imagine Greaves and MacAskill in front of two buttons. If pushed, the first would save the lives of 1 million living, breathing, actual people. The second would increase the probability that 1014 currently unborn people come into existence in the far future by a teeny-tiny amount. Because, on their longtermist view, there is no fundamental moral difference between saving actual people

and bringing new people into existence, these options are morally equivalent.

And, according to longtermists, this is why we shouldn’t worry too much about climate change as long as we survive to fulfill our potential. (I think most futurists worrying about the short-term implications of climate change regardless of whether there is a runaway greenhouse scenario. I also think that it is difficult to know where to put your resources. How much to mitigate the effects of climate change and how much to other scientific research? It is hard to know the optimal strategy.)

However, Torres finds all this appalling. He sees “longtermism as an immensely dangerous ideology.” It is a secular religion that worships future value and comes complete with its own doctrine of salvation—that we will live forever as posthumans. Moreover, numerous EAs have argued, “that we should care more about people in rich countries than poor countries.” This is primarily because the workers in rich countries are more innovative and productive.

So while climate change is bad, longtermists generally worry more about AI. In fact, many longtermists not only believe

believe that superintelligent machines pose the greatest single hazard to human survival, but they seem convinced that if humanity were to create a “friendly” superintelligence whose goals are properly “aligned” with our “human goals,” then a new Utopian age of unprecedented security and flourishing would suddenly commence.

The idea is that friendly superintelligence could eliminate or reduce all existential risks. As Bostrom writes “One might believe … the new civilization would [thus] have vastly improved survival prospects since it would be guided by superintelligent foresight and planning.” Other futurists share this view—advancing AI is the best way to bring about a good future.

But Torres objects to the potential “for a genocidal catastrophe in the name of realizing astronomical amounts of far-future “value.” He also objects to those who believe that longtermism “is so important that they have little tolerance for dissenters.” These true believers minimize both past and present suffering in the name of dogma. And he especially objects to “the ends justify the means” ethics that underlies all this. Again, he is not saying we shouldn’t care about the future, but that he doesn’t want to

genuflect before the altar of “future value” or “our potential,” understood in techno-Utopian terms of colonizing space, becoming posthuman, subjugating the natural world, maximizing economic productivity, and creating massive computer simulations …

Avoiding the untold suffering that climate change will cause “requires immediate action from the Global North. Meanwhile, millionaires and billionaires under the influence of longtermist thinking are focused instead on superintelligent machines that they believe will magically solve the mess that, in large part, they themselves have created.”

Brief Reply

I’m not convinced by Torres’ argument. I am a transhumanist who believes that we must use future technologies to have any chance at survival and flourishing for ourselves and our descendants. I agree we shouldn’t minimize past or future suffering, and we should do everything possible to ameliorate or eliminate it, but it seems to me that we can both mitigate the effects of climate change and advance scientific research in AI simultaneously.

I would also say that we would live in a better world if most of the GDP produced in the world was invested in scientific research, including a massive worldwide effort to subsidize the education of future scientists, pay them extraordinarily well, and educate the populace in scientific matters. As I’ve said many times in this blog … we either evolve or we will die.

(Note – Torres has further explained these themes in a new essay “Against Longtermism.”)

October 24, 2021

The Monopoly Experiment: Wealthy People Are More Selfish

[image error]

Does having more money make a person more inclined to share their wealth with others and acknowledge their good fortune? No. Research suggests precisely the opposite.

One experiment by psychologists at the University of California, Irvine, invited pairs of strangers to play a rigged Monopoly game where a coin flip designated one player rich and one poor. The rich players received twice as much money as their opponent to begin with; as they played the game, they got to roll two dice instead of one and move around the board twice as fast as their opponent; when they passed “Go,” they collected $200 to their opponent’s $100.

Now did the inevitable winners ascribe their winning to good luck—to their head start in the game? No. Instead, they believed they deserved their money and the others deserved their fate. The winners had no empathy for the losers.

I must say I don’t find this surprising. Consider, for example, how we have a word for when we fail at something perhaps because of bad luck—excuse. Failing to arrive on time may really have been because of an accident on the freeway or an inordinate amount of traffic. Perhaps the dog really did eat my homework. Why don’t I play professional basketball? My excuse is that I wasn’t born with the genes that in large part would have allowed me to.

Notice though we don’t have a word to eliminate credit. We might say we achieved this or that because we were, in large part, lucky. But consider how often instead we say that we achieved because we were smart, perseverant, amiable, or we were just winners. We tend to take credit for our successes but not for our failures.

If interested here is the TED Talk b the social psychologist Paul Piff sharing his research into how people behave when they feel wealthy.

October 20, 2021

The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality

A friend alerted me to an interview with Kathryn Paige Harden, a psychology professor at the University of Texas at Austin. The interview concerns her new book The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality.

Harden “argues how far we go in formal education – and the huge knock-on effects that has on our income, employment and health – is in part down to our genes. And she estimates that genetic differences “captures about 10-15% of the variance in educational attainment.”

Let me state at the outset that I have not read the book. Still, I need no convincing about the pull of genes on behavior. As E.O.Wilson says “genes hold culture on a lease.” I’m not a genetic determinist, but anyone who denies the effect of how genes wire our bodies and brains simply doesn’t know what they’re talking about. Humans act very much like other primates in so so many ways. That our basic biology affects our social behaviors—sex, aggression, ethics, religion, and more—is indisputable. I readily acknowledge, regarding this specific case, that my desire to become educated rather than say pursuing wealth was, in large part, heavily influenced by my genetic wiring.

Still, this genome was also in an environment—my parents sent me to good schools and emphasized doing my homework! And it was also influenced by having enough food in my stomach, growing up in a middle-class home, having access to quality public college at a modest cost. (The University of Missouri cost about $250 a semester in 1973 when I started college.) And these in turn were influenced by my dad being paid union wages as a butcher, taxes to support education, no cracking lead paint on my school walls, etc.

So much more to say about the nature/nurture debates but to say that we are genomes in environments isn’t very controversial. Of course, there is probably randomness built into the system too. At any rate, so much comes down to our basic nature which is why I don’t see how we can survive and flourish unless we augment/transform our basic nature. And I know this is a radical solution.

_________________________________________________________________________

For a deeper look into the ideas in Harden’s book see “Can Progressives Be Convinced That Genetics Matters?” in the New Yorker.)

October 15, 2021

Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn’s: “Ars Vitae”

[image error]

A reader alerted me to a new book, Ars Vitae: The Fate of Inwardness and the Return of the Ancient Arts of Living. The author is Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn, a professor of history and senior research associate at the Campbell Public Affairs Institute, Syracuse University.

[image error]

Here is a brief description.

The ancient Roman philosopher Cicero wrote that philosophy is ars vitae, the art of living. Today, signs of stress and duress point to a full-fledged crisis for individuals and communities while current modes of making sense of our lives prove inadequate. Yet, in this time of alienation and spiritual longing, we can glimpse signs of a renewed interest in ancient approaches to the art of living.

In this ambitious and timely book, Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn engages both general readers and scholars on the topic of well-being. She examines the reappearance of ancient philosophical thought in contemporary American culture, probing whether new stirrings of Gnosticism, Stoicism, Epicureanism, Cynicism, and Platonism present a true alternative to our current therapeutic culture of self-help and consumerism, which elevates the self’s needs and desires yet fails to deliver on its promises of happiness and healing. Do the ancient philosophies represent a counter-tradition to today’s culture, auguring a new cultural vibrancy, or do they merely solidify a modern way of life that has little use for inwardness―the cultivation of an inner life―stemming from those older traditions? Tracing the contours of this cultural resurgence and exploring a range of sources, from scholarship to self-help manuals, films, and other artifacts of popular culture, this book sees the different schools as organically interrelated and asks whether, taken together, they can point us in important new directions.

Having taught Greek philosophy for more than 30 years I found myself wishing I had the time to read the entire work. Let me say that of all the Western philosophy I’ve studied ancient Greek and Roman philosophy provided the best insights concerning how to live well.1 But of course, I do not have that time. Aging has led to the realization that I must pick and choose what I learn, read, and write about. I’m reminded of my graduate school mentor Richard Blackwell‘s advice. He told me that when contemplating the course of his future research after being awarded an endowed chair in his late 50s, he was strongly pulled to doing philosophy of biology. However, he thought that it would take too long to do all the background research to master that field. Instead, he choose to combine his vast knowledge of history, foreign languages, philosophy of science to research the Galileo affair (for which he became well-known.)

Anyway, I get many great suggestions from readers about good books but alas there just isn’t time to read everything. Now in my mid-60s I simply have to pick and choose. Oh to have more time or a better mind or to be part of a global brain, etc.

__________________________________________________________

1. Here is a sampling of some of the posts I’ve published about ancient philosophy on living well.

October 13, 2021

Profound Essays from Aeon Magazine

[image error]

Over the last year, I have found many good articles at Aeon—a digital magazine of ideas, philosophy, and culture. I had intended to write posts about these many pieces but alas I have not found the time. So instead I will link to some of the thought-provoking pieces they’ve published that I’ve read followed by a single sentence description of their content.

“What Animals Think of Death” (Animals wrestle with the concept of death and mortality.)

“Do We Send The Goo?” (If we’re alone in the universe should we do anything about it?)

“The Mind Does Not Exist” (Why there’s no such thing as the mind and nothing is mental.)

“You Are A Network” (The self is not singular but a fluid network of identities.)

“After Neurodiversity” (Neurodiversity is not enough, we should embrace psydiversity.)

“Lies And Honest Mistakes” (Our epistemic crisis is essentially ethical and so are its solutions.)

“Ideas That Work” (Our most abstract concepts emerged as solutions to our needs.)

“We Are Nature” (Even the Anthropocene is nature at work transforming itself.)

“The Seed Of Suffering” (What the p-factor says about the root of all mental illness.)

“Authenticity Is A Sham” (A history of authenticity from Jesus to self-help and beyond.)

“Who Counts As A Victim?” (The pantomime drama of victims and villains conceals the real horrors of war.)

“Nihilism” (If you believe in nihilism do you believe in anything?)

“The Science Of Wisdom” (How psychologists have found the empirical path to wisdom.)

“The Semi-Satisfied Life” (For Schopenhauer happiness is a state of semi-satisfaction.)

“Bonfire Of The Humanities” (The role of history in a society afflicted by short-termism.)

“How Cosmic Is The Cosmos?” (Can Buddhism explain what came before the big bang?)

“Is The Universe A Conscious Mind?” (Cosmopsychism explains why the universe is fine-tuned for life.)

“Dreadful Dads” (What the childless fathers of existentialism teach real dads.)

“End of Story” (How does an atheist tell his son about death?)

“Buddhism And Self-Deception” (How Buddhism resolves the paradox of self-deception.)

“The happiness ruse” (How did feeling good become a matter of relentless, competitive work?”)

“How to be an Epicurean” (Forget Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics; try being an Epicurean.)

“The Greatest Use of Life” (William James on whether life is worth living.)

“Anger is temporary madness: the Stoics knew how to curb it” (How to Avoid the triggers.)

“Faith: Why Is the Language of Transhumanism and Religion So Similar?” (AI and religion.)

“Endless Fun” (What will we do for all eternity after uploading?)

“There Is No Death, Only A Series of Eternal ‘Nows'” (You don’t actually die.)

“Save The Universe” (It’s only a matter of time until it dies.)

“When Hope is a Hindrance” (Hope in dark times is no match for action.)

Oh, to have more time to read and learn.