John G. Messerly's Blog, page 35

July 7, 2021

Some Kind of Heaven

I recently saw the new movie, Some Kind of Heaven, which was an Official Selection of the 2020 Sundance Film Festival. It is about the Florida retirement community known as The Villages. Here is the official trailer:

My main reactions to the film were 1) it sounds like a slice of hell to me; 2) I love my wife more than ever; and 3) people are often confused about the nature of happiness and meaning.

First, let me say that while many retirees are undoubtedly happy there a life of continual adolescence doesn’t interest me. Yes, I enjoy playing golf—my one hobby—but I don’t want to do it every day. Nor do I want to become the actor, cheerleader, or dancer I never became or party and drink margaritas every evening. And I most definitely don’t want to live in a world without children.

Second I couldn’t help but contrast the life my wife spends in service to others with the lives lived in this retirement cocoon. While my wife’s labors are tiring and frustrating at times they give her life meaning. And I’d like to think that the time I take to write on my blog has meaning for some readers; I know it is meaningful to me. I’d much rather do work that I love, enjoy my relationships with family, and try to better understand life than perpetually partying. That seems to be just a diversion from life in all its varied tapestry.

Now I know that people find joy in different things. But there is a long tradition in Western philosophy that sees happiness as a byproduct of doing meaningful things–not as something to be directly sought. My sense was that many of these retirees seek happiness directly and forget that true happiness—contentment and inner peace—is found as a byproduct of meaningful work and loving relationships. You can move to Florida or Hawaii but in the end, you take yourself with you and only find true meaning to the extent you cultivate it within.

There’s a lot more to be said but you won’t find me heading to The Villages. (“Where dreams come true” is their motto). Here is a link if you’d like to buy or rent the video.

July 1, 2021

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

[image error]The prisoner’s dilemma as a briefcase exchange

(I think the PD sheds light on so much of human life. We continuously find ourselves in situations with its structure. Here is a brief explanation of the PD.)

Game Theory

For our purposes, a game is an interactive situation in which individuals, called players, choose strategies to deal with each other in attempting to maximize their individual utility. There are several ways of distinguishing games including: 1) in respect to the number of players involved; 2) in respect to the number of repetitions of play; 3) in respect of the order of the various player’s preferences over the same outcomes. On the one extreme are games of pure conflict, so-called zero-sum games, in which players have completely opposing interests over possible outcomes. On the other extreme are games of pure harmony, so-called games of coordination. In the middle are games involving both conflict and harmony in respect of others. It is one particular game that interests us most, since it describes the situation in Hobbes’ state of nature, and is the central problem in contractarian moral theory.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The prisoner’s dilemma is one of the most widely debated situations in game theory. The story has implications for a variety of human interactive situations. A prisoner’s dilemma is an interactive situation in which it is better for all to cooperate rather than for no one to do so, yet it is best for each not to cooperate, regardless of what the others do.

In the classic story, two prisoners have committed a serious crime but all of the evidence necessary to convict them is not admissible in court. Both prisoners are held separately and are unable to communicate. The prisoners are called separately by the authorities and each offered the same pro-position. Confess and if your partner does not, you will be convicted of a lesser crime and serve one year in jail while the unrepentant prisoner will be convicted of a more serious crime and serve ten years. If you do not confess and your partner does, then it is you who will be convicted of the more serious crime and your partner of the lesser crime. Should neither of you confess the penalty will be two years for each of you, but should both of you confess the penalty will be five years. In the following matrix, you are the row chooser and your partner the column chooser. The first number in each parenthesis represents the “payoff” for you in years in prison, the second number your partner’s years. Let us assume each player prefers the least number of years in prison possible. In matrix form, the situation looks like this:

Prisoner 2

Confess

Don’t Confess

Prisoner 1

Confess

(5, 5)

(1, 10)

Don’t Confess

(10, 1)

(2, 2)

So you reason as follows: If your partner confesses, you had better confess because if you don’t you will get 10 years rather than 5. If your partner doesn’t confess, again you should confess because you will only get 1 year rather than 2 for not confessing. So no matter what your partner does, you ought to confess. The reasoning is the same for your partner. The problem is that when both confess the outcome is worse for both than if neither confessed. You both could have done better, and neither of you worse, if you had not confessed! You might have made an agreement not to confess but this would not solve the problem. The reason is this: although agreeing not to confess is rational, compliance is surely not rational!

The prisoner’s dilemma describes the situation that humans found themselves in in Hobbes’ state of nature. If the prisoners cooperate, they both do better; if they do not cooperate, they both do worse. But both have a good reason not to cooperate; they are not sure the other will! We can only escape this dilemma, Hobbes maintained, by installing a coercive power that makes us comply with our agreements (contracts). Others, like the contemporary philosopher David Gauthier, argue for the rationality of voluntary non-coerced cooperation and compliance with agreements given the costs to each of us of enforcement agencies. Gauthier advocates that we accept “morals by agreement.”

June 26, 2021

Seattle Heat Wave

[image error]

Temperature anomalies, March to May 2007

I’m currently living in the great Seattle heatwave. Seattle averages only 3 days a year over 90 degrees Fahrenheit and even then it typically goes down into the 60s at night. In the 11 years we’ve lived here we’ve never hit 100 degrees, and snever really been hot at night.

In fact, Seattle has experienced temperatures of 100 or more only three times since the late 1800s, when record-keeping began, and the all-time hottest temperature in Seattle is 103 degrees, set back in late July 2009. (And, as you may know, Seattle homes are less likely to be air-conditioned than any other major American city.)

Still, we have electrical power for our refrigerator, cold water available in the shower, and one of our kids has a/c if we get too hot. However, I must admit to feeling a bit more lethargic than usual and not motivated to think and write about the meaning of life. I’m thinking more of ways to stay cool! I’m guessing there’s a lesson in that; perhaps that concerns about life’s meaning arise only after our survival needs are met.

Yet this unique situation is kinda fun too. Sort of like went the power goes out. It’s so different that it gives you the opportunity to learn from and experience something different. Of course, I hope the power doesn’t go out because that would mean no cold water.

Life is mysterious, I’ll never understand more than a little of it, but I’ve been very fortunate. I’ve received more love than I deserved; I learned a little; and I’ve found joy in helping others. There are many things I didn’t love that I should have; many things I should have learned but didn’t; many people I should have helped but wasn’t able to.

All this makes me think of Ted Kennedy’s eulogy for his brother Robert. I have never heard it without being profoundly moved.

“My brother need not be idealized, or enlarged in death beyond what he was in life; to be remembered simply as a good and decent man, who saw wrong and tried to right it, saw suffering and tried to heal it, saw war and tried to stop it.

Those of us who loved him and who take him to his rest today, pray that what he was to us and what he wished for others will some day come to pass for all the world.

As he said many times, in many parts of this nation, to those he touched and who sought to touch him:

Some men see things as they are and say why.

I dream things that never were and say why not.

June 23, 2021

Good Writing

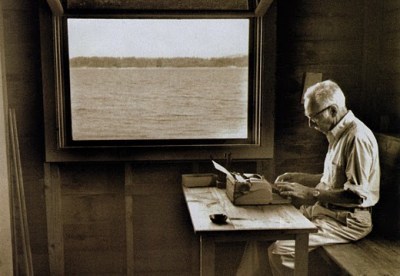

E. B. White (1899 – 1977) at age 77, writing in the boathouse of his home in Maine.

E. B. White (1899 – 1977) at age 77, writing in the boathouse of his home in Maine.

I learned most of what I know about writing from two books: William Strunk and E.B. White’s The Elements of Style, and William Zinsser’s On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction.

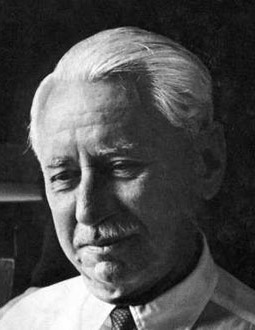

William Zinsser (1922 – 2015 ) age 86, writing in his Manhattan office.

From Strunk and White I learned the essence of good writing in three sentences:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that [writers] make all [their] sentences short, or that [they] avoid all detail and treat [their] subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

From Zinsser I learned the process of good writing from sentences like these :

Good writing doesn’t come naturally, though most people seem to think it does … Writing is hard work. A clear sentence is no accident. Very few sentences come out right the first time, or even the third time. Remember this in moments of despair. If you find that writing is hard, it’s because it is hard.

I also learned a lot about writing from a graduate school mentor, William B. Charron. He made me rewrite my master’s thesis about ten times. Literally! The process was laborious, but the end product was carefully and conscientiously crafted—all of its chapters were published in peer-reviewed professional journals. He pored over my every word with diligence, and my writing was the beneficiary. I thank him.

June 16, 2021

Great Prose

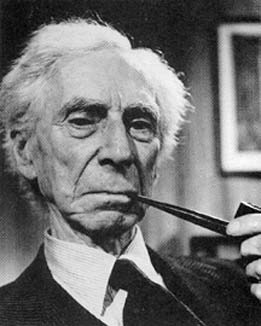

Will Durant Bertrand Russell

Here are examples of great writing about the value of philosophy from two great prose stylists Will Durant and Bertrand Russell. (Who are also two of my intellectual heroes.) The first is from the introduction to Durant’s The Pleasures of Philosophy (1929), and the second is from the final chapter of Russell’s classic, The Problems of Philosophy (1912). I’ll let their beautiful prose speak for itself.

The busy reader will ask, is all this philosophy useful? It is a shameful question: we do not ask it of poetry, which is also an imaginative construction of a world incompletely known. If poetry reveals to us the beauty our untaught eyes have missed and philosophy gives us the wisdom to understand and forgive, it is enough, and more than the worlds wealth. Philosophy will not fatten our purses nor lift us to dizzy dignities in a democratic state; it may even make us a little careless of these things. For what if we should fatten our purses, or rise to high office and yet all the while remain ignorantly naive, coarsely unfurnished in the mind, brutal in behavior, unstable in character, chaotic in desire and blindly miserable? …

Our culture is superficial today and our knowledge dangerous, because we are rich in mechanism and poor in purposes. the balance of mind which once came of a warm religious faith is gone; science has taken from us the supernatural bases of our morality and all the world seems consumed in a disorderly individualism that reflects the chaotic fragmentation of our character.

We face again the problem that harassed Socrates: how shall we find a natural ethic to replace the supernatural sanctions that have ceased to influence the behavior of men? Without philosophy, without that total vision which unifies purposes and establishes the hierarchy of desires we fritter away our social heritage in cynical corruption on the one hand and in revolutionary madness on the other; we abandon in a moment our idealism and plunge into the cooperative suicide of war; we have a hundred thousand politicians, and not a single statesman.

We move about the earth with unprecedented speed, but we do not know, and have not thought where we are going, or whether we shall find any happiness there for our harrassed souls. We are being destroyed by our knowledge which has made us drunk with our power, and we shall not be saved without wisdom.

And now we hear from Russell:

The value of philosophy is, in fact, to be sought largely in its very uncertainty. The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. As soon as we begin to philosophize, on the contrary, we find, as we saw in our opening chapters, that even the most everyday things lead to problems to which only very incomplete answers can be given. Philosophy, though unable to tell us with certainty what is the true answer to the doubts which it raises, is able to suggest many possibilities which enlarge our thoughts and free them from the tyranny of custom. Thus, while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are, it greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt, and it keeps alive our sense of wonder by showing familiar things in an unfamiliar aspect.

Apart from its utility in showing unsuspected possibilities, philosophy has a value — perhaps its chief value — through the greatness of the objects which it contemplates, and the freedom from narrow and personal aims resulting from this contemplation. The life of the instinctive man is shut up within the circle of his private interests: family and friends may be included, but the outer world is not regarded except as it may help or hinder what comes within the circle of instinctive wishes. In such a life there is something feverish and confined, in comparison with which the philosophic life is calm and free. The private world of instinctive interests is a small one, set in the midst of a great and powerful world which must, sooner or later, lay our private world in ruins. Unless we can so enlarge our interests as to include the whole outer world, we remain like a garrison in a beleagured fortress, knowing that the enemy prevents escape and that ultimate surrender is inevitable. In such a life there is no peace, but a constant strife between the insistence of desire and the powerlessness of will. In one way or another, if our life is to be great and free, we must escape this prison and this strife.

One way of escape is by philosophic contemplation. Philosophic contemplation does not, in its widest survey, divide the universe into two hostile camps — friends and foes, helpful and hostile, good and bad — it views the whole impartially. Philosophic contemplation, when it is unalloyed, does not aim at proving that the rest of the universe is akin to man. All acquisition of knowledge is an enlargement of the Self, but this enlargement is best attained when it is not directly sought. It is obtained when the desire for knowledge is alone operative, by a study which does not wish in advance that its objects should have this or that character, but adapts the Self to the characters which it finds in its objects. This enlargement of Self is not obtained when, taking the Self as it is, we try to show that the world is so similar to this Self that knowledge of it is possible without any admission of what seems alien. The desire to prove this is a form of self-assertion and, like all self-assertion, it is an obstacle to the growth of Self which it desires, and of which the Self knows that it is capable. Self-assertion, in philosophic speculation as elsewhere, views the world as a means to its own ends; thus it makes the world of less account than Self, and the Self sets bounds to the greatness of its goods. In contemplation, on the contrary, we start from the not-Self, and through its greatness the boundaries of Self are enlarged; through the infinity of the universe the mind which contemplates it achieves some share in infinity.

For this reason greatness of soul is not fostered by those philosophies which assimilate the universe to Man. Knowledge is a form of union of Self and not-Self; like all union, it is impaired by dominion, and therefore by any attempt to force the universe into conformity with what we find in ourselves. There is a widespread philosophical tendency towards the view which tells us that Man is the measure of all things, that truth is man-made, that space and time and the world of universals are properties of the mind, and that, if there be anything not created by the mind, it is unknowable and of no account for us. This view, if our previous discussions were correct, is untrue; but in addition to being untrue, it has the effect of robbing philosophic contemplation of all that gives it value, since it fetters contemplation to Self. What it calls knowledge is not a union with the not-Self, but a set of prejudices, habits, and desires, making an impenetrable veil between us and the world beyond. The man who finds pleasure in such a theory of knowledge is like the man who never leaves the domestic circle for fear his word might not be law.

The true philosophic contemplation, on the contrary, finds its satisfaction in every enlargement of the not-Self, in everything that magnifies the objects contemplated, and thereby the subject contemplating. Everything, in contemplation, that is personal or private, everything that depends upon habit, self-interest, or desire, distorts the object, and hence impairs the union which the intellect seeks. By thus making a barrier between subject and object, such personal and private things become a prison to the intellect. The free intellect will see as God might see, without a here and now, without hopes and fears, without the trammels of customary beliefs and traditional prejudices, calmly, dispassionately, in the sole and exclusive desire of knowledge — knowledge as impersonal, as purely contemplative, as it is possible for man to attain. Hence also the free intellect will value more the abstract and universal knowledge into which the accidents of private history do not enter, than the knowledge brought by the senses, and dependent, as such knowledge must be, upon an exclusive and personal point of view and a body whose sense-organs distort as much as they reveal.

The mind which has become accustomed to the freedom and impartiality of philosophic contemplation will preserve something of the same freedom and impartiality in the world of action and emotion. It will view its purposes and desires as parts of the whole, with the absence of insistence that results from seeing them as infinitesimal fragments in a world of which all the rest is unaffected by any one man’s deeds. The impartiality which, in contemplation, is the unalloyed desire for truth, is the very same quality of mind which, in action, is justice, and in emotion is that universal love which can be given to all, and not only to those who are judged useful or admirable. Thus contemplation enlarges not only the objects of our thoughts, but also the objects of our actions and our affections: it makes us citizens of the universe, not only of one walled city at war with all the rest. In this citizenship of the universe consists man’s true freedom, and his liberation from the thraldom of narrow hopes and fears.

Thus, to sum up our discussion of the value of philosophy; Philosophy is to be studied, not for the sake of any definite answers to its questions since no definite answers can, as a rule, be known to be true, but rather for the sake of the questions themselves; because these questions enlarge our conception of what is possible, enrich our intellectual imagination and diminish the dogmatic assurance which closes the mind against speculation; but above all because, through the greatness of the universe which philosophy contemplates, the mind also is rendered great, and becomes capable of that union with the universe which constitutes its highest good.

June 9, 2021

Finding Fulfilling Work

How to Find Fulfilling Work (The School of Life)

My Previous Advice – One of the most difficult things tasks for most of us is finding fulfilling (paid) work in our modern economic system. (If you don’t have this problem fine, but many people do.) I addressed this topic previously in my most post: “Should You Do What You Love?” Here was my conclusion in that piece:

I agree with Marino that doing our duty, even if it doesn’t make us happy, is admirable. And I agree with Tokumitsu and Hanson that elitists, who often do the most interesting work, fail to value more mundane work. But I think that Linsenmayer makes the most important point. We need a new economic system–one where we can develop our talents and actualize our potential. Most of us are too good for the work we do, not because we are better than others, but because the work available in our current system is not good enough for any of us. (I have written about his previously.)

Still we do not live in an ideal world. So what practical counsel do we give others, in our current time and place? Unfortunately my advice is dull and unremarkable, like so much of the available work. For now the best recommendation is something like: do the least objectionable/most satisfying work available given your options. That we can’t say more reveals the gap between the real and the ideal; it is symptomatic of a flawed society. Perhaps working to change the world so that people can engage in satisfying work is the most meaningful work of all.

More Thoughts – First a disclaimer. I am not an expert on the topic of satisfying work and I lack the time for a thorough investigation of the topic. But social science research must have been done on what work people generally find fulfilling, on the difference between work and leisure activities; on work and its compatibility with personality profiles like the Big 5, and related topics. Those interested should consult this research. With these caveats in place, here are a few reflections.

What is work? – It is activity, usually engaged in for the money which buys the things we need to survive. We typically contrast work with leisure, which is activity or inactivity usually engaged in, not for money, but for enjoyment. Of course what we call work activity or leisure activity might conflict or coincide. We might engage in activities we enjoy and make money in the process—our work and our leisure activities may coincide. Yet they might conflict too. We might enjoy playing golf and hate being a lawyer—engaging in the latter for the sole purpose of making money to engage in the former. But surely most of us in the first world, when confronted with a countless variety of activities in which to engage, can find something we (somewhat) enjoy that also makes money.

Are We Lucky to Have a Job? – This is a tough question. For those in the world who subsist on less than $2 a day—about half the world’s population—any work that paid almost anything would seem to be a blessing. Desperate people might consider themselves lucky to make a few thousand dollars a year picking fruit all day in the hot sun. From the perspective of those in poverty, those who would reject a $100,000 a year job (in US dollars) in good working conditions because it wasn’t satisfying enough, would elicit no sympathy. (They might even considered such individuals entitled.) Nor would those who insist on satisfying work elicit sympathy from full-time workers making the USA minimum wage, which typically involves unfulfilling work. Still it is hard to tell someone they should be satisfied with work they don’t find satisfying. By all means if the opportunity presents itself, and you would not hurt yourself or others, accept more fulfilling work.

Is the World Economic System Immoral? – One might advance a stronger argument against working at all—that participating in the world’s economic system is intrinsically immoral. If participating in an economic system they deem unjust violates one’s conscience, then perhaps they shouldn’t do that work. Of course they have to ask themselves whether they really believe this or whether it is an excuse to avoid doing something they don’t like. But if it is the former, then possibly they shouldn’t violate their conscience.

I say possibly because there are all sorts of reasons to do what you don’t want to do, or even do what you think is immoral. As for doing what you don’t want to, the idea of duty has a long history as a significant concept in moral philosophy that dates back at least to the Stoics. And even if you think the economic system is immoral you might still want to participate in it to feed your family. Surely there is also something immoral about allowing your family to starve, not have adequate nutrition, not live in a good neighborhood or get a good education. Especially when you have the ability to avoid such outcomes.

Moreover, you really don’t know that participating in an imperfect world economic system is immoral. There is substance to the counter argument that participation in the world’s economic system, despite its flaws, has merit. For surely something about that system has contributed positively to the world we now live in. And what kind of world is that? It is one in which more people live longer and more fulfilling lives while doing reasonably satisfying work than at any time in human history. (If you don’t believe this, take your family back to Europe in the Middle Ages or ancient Greece or Rome or the plains of Africa where the average lifespan was vanishingly short, where mothers died in childbirth, children died en masse of disease, and there was little time for high cultural achievements like art, literature, music, philosophy, and science.)

Now the extent to which these positive transformations were caused by economic systems is debatable—perhaps science and technology played a more important role in driving human history. (I think they did.) But economics, technology, and other elements of culture interact. It is hard to disentangle which have played the most important role in leading to the better world we now live in. But our long journey—from the agricultural revolution, which produced the excess food which allowed for priests, philosophers, artisans and scientists; to the industrial revolution, which mass-produced the technology that transformed the world; to the current technological revolution, which will transform reality in ways as yet unimaginable—together have produced a better world. And some part of that transformation must have been played by commerce, business, lending, and money. I don’t possess the wherewithal to defend this argument in detail, but these comments should at least plant doubt in the minds of those who assume that the modern economic system is intrinsically immoral. It is easy to be influenced by half-true memes.

Now I am not an apologist for predatory capitalism, the profit motive, or the genocide and slavery which it was and still is associated. I don’t know on balance if it is a good or bad thing. I just know that the truth about such issues is complex. What part does our evolutionary biology play and what part do the various elements of culture play in our imperfect world? Again, I don’t know. But given the complexity of the issue it would be foolish to not participate in the system as best we can. (There are many ways to do this which I’ll describe below.) In fact, other than opting out of life entirely, it isn’t possible to live disentangled from the world’s economy. Even Thoreau determined to live according to his conscience and often far from the world said, “I came into this world, not chiefly to make this a good place to live in, but to live in it, be it good or bad.” He wanted to change the world, but had to make peace with it too.

What work is fulfilling? – In my own life reading, writing, thinking and teaching philosophy were activities that, for the most part, I enjoyed. Of course nothing is perfect. I had students over the years that I strongly disliked, department chairs who were tyrants, and I’ve read books and took classes that I wasn’t thrilled about. (Oh, those mandatory medieval philosophy classes—how little I remember you, St. Bonaventure!) Surely many feel similarly about being a physician, nurse, biologist, economist, public policy expert or psychologist—not perfect jobs in a perfect world, but satisfying nonetheless. And I’m not prejudice toward white-collar jobs either. There are plumbers, electricians, carpenters and others who feel the same way—they may not have perfect jobs, but they find satisfaction in the honest work that feeds their families. (One of my graduate student friends who was good at fixing things said he found working with his hands as satisfying as philosophy—and he was the best grad student in our program.) I also found raising my children to be some of the most satisfying work I did. I enjoyed every moment of taking them to gymnastics and football games, playing softball and basketball with them, and of course discussing philosophy with them.

What work if fulling for me? – Obviously this depends on one’s personality traits, talents, psychology, opportunities, culture, history, genes and more. I mentioned the Big 5 personality test earlier and I’m sure there is information about one’s personality profile and fulfilling work. (There are multiple books about the connection between one’s Myers-Briggs profile and job satisfaction, but as I understand it, the Big 5 is the more scientific test.)

Again for most of us, if we are reasonably intelligent, physically healthy, and lucky enough to live in a thriving economy and not to have to work for minimum (virtual slave) wages in those economies, then there are a plethora of choices. (Of course overchoice does makes choosing tougher.) In the end all we can do is look at the available choices—assuming we are lucky enough to have them—and choose. It probably doesn’t matter much what we choose, as long as it is something that contributes ever so slightly to keeping civilization going. (We might experience existential guilt by working, thinking that we are denying others the opportunity, but we must value ourselves too. And we must avoid what the Dalai Lama calls “sloppy sympathy,” feeling bad for others. Such sentiments are worthless. Much better to use your skill, go out in the world, and help someone.)

Playing Our Small Role – In the end we are small creatures and the universe is big. We can’t change the whole world but we can influence it through our interaction with those closest to us, finding joy in the process. We may not change the world by administering to the sick as doctors or nurses or psychologists, or by installing someone’s dishwasher or cleaning their teeth or keeping their internet running. We may not even change it by caring lovingly for our children. But the recipients of such labors may find your work significant indeed. For they received medical care or had someone to talk to or had their teeth cleaned. Or they met an old friend on the internet. Or they don’t have to go to the laundromat anymore. Or they grew up to be the kind of functioning adult this world so desperately needs because of that loving parental care. These may all be small things, but if they are not important, nothing is.

Perhaps then it is the sum total of our labors that makes us large. Our labors are not always sexy, but they are necessary to bring about a better future. All those mothers who cared for children and fathers who worked to support them, all those plumbers and doctors and nurses and teachers and firefighters doing their little part in the cosmic dance. All of them recognizing what Victor Frankl taught, that productive work is a constitutive element of a meaningful life.

June 6, 2021

Descartes’ Third Maxim

I know of know better statement of Stoic philosophy than what follows—the 3rd maxim by which Descartes lived his life. It is truly a piece of wisdom. Three very long sentences but they are worth continual re-reading.

My third maxim was to endeavor always to conquer myself rather than fortune, and change my desires rather than the order of the world, and in general, accustom myself to the persuasion that, except our own thoughts, there is nothing absolutely in our power; so that when we have done our best in things external to us, all wherein we fail of success is to be held, as regards us, absolutely impossible: and this single principle seemed to me sufficient to prevent me from desiring for the future anything which I could not obtain, and thus render me contented; for since our will naturally seeks those objects alone which the understanding represents as in some way possible of attainment, it is plain, that if we consider all external goods as equally beyond our power, we shall no more regret the absence of such goods as seem due to our birth, when deprived of them without any fault of ours, than our not possessing the kingdoms of China or Mexico, and thus making, so to speak, a virtue of necessity, we shall no more desire health in disease, or freedom in imprisonment, than we now do bodies incorruptible as diamonds, or the wings of birds to fly with.

But I confess there is need of prolonged discipline and frequently repeated meditation to accustom the mind to view all objects in this light; and I believe that in this chiefly consisted the secret of the power of such philosophers as in former times were enabled to rise superior to the influence of fortune, and, amid suffering and poverty, enjoy a happiness which their gods might have envied.

For, occupied incessantly with the consideration of the limits prescribed to their power by nature, they became so entirely convinced that nothing was at their disposal except their own thoughts, that this conviction was of itself sufficient to prevent their entertaining any desire of other objects; and over their thoughts they acquired a sway so absolute, that they had some ground on this account for esteeming themselves more rich and more powerful, more free and more happy, than other men who, whatever be the favors heaped on them by nature and fortune, if destitute of this philosophy, can never command the realization of all their desires.

(From Rene Descartes The Discourse of Method, Chapter 3.)

June 2, 2021

How Close Can You Be To Another Person?

[image error]

Kahlil Gibran

We never have perfect relationships with others. We might find that we can discuss sports or the weather with some acquaintances, but any more substantive topics get us into trouble. We might say we can have a “2” relationship with them.

We might also have good friends with whom we can discuss a variety of things, perhaps we are even close with them, but religion, politics, and personal critique are off-limits. We may wish that we could be more honest with them but decide that avoiding conflict over these more substantive or personal issues is wise. With these friends or family members we might have a “5” relationship.

With our closest friends or confidants we might find that we can share almost anything without either party becoming upset or defensive. Still there might be a few personal topics or activities off-limits. Perhaps you have a “8” relationship with them. With our spouses of many years, we might find that they are almost another self; perhaps we have a “9” with them.

You might claim that you have a “10” relationship with yourself, but this is false. We all engage in self-deception, we are all motivated by irrational and unknown forces as Freud taught us a century ago. In fact others often know you better than you know yourself. I’m sure this ultimately has to do with our lack of complete knowledge about the world.

So it’s not possible to have a “10” relationship with anyone—unless you undergo a Vulcan mind meld with them! But is this a good or a bad thing, this lack of complete unity with others? Kahlil Gibran’s poetry seems to suggest it makes for a lonely life:

Life is an island in an ocean of loneliness, an island whose rocks are hopes, whose trees are dreams, whose flowers are solitude, and whose brooks are thirst. Your life, my fellow men, is an island separated from all other island and regions. No matter how many are the ships that leave our shores for other climes, no matter how many are the fleets that touch your coast, you remain a solitary island, suffering the pangs of loneliness and yearning for happiness. You are unknown to your fellow mean and far removed from their sympathy and understanding.

But perhaps it is not so bad either. Gibran concludes his little section “on life” with the following:

Your spirit’s life, my brother, is encompassed by loneliness, and were it not for that loneliness and solitude, you would not be you, nor would I be I. Were it not for this loneliness and solitude, I would come to believe on hearing your voice that it was my voice speaking,; or seeing your face, that it was myself looking into a mirror.

So Gibran thought that separation and loneliness are the price we pay for individualism. But is this price too high to? I didn’t think so when I first read Gibran more than 40 years ago, but I do now. We can be joined or separated. The more we are separated the more individual and lonely we become; the more joined the less individual and more connected we become. In the end we must hope that it is possible to remain a separate raindrop while merging into an ocean of being. (If we are allowed such a metaphor.) Thus we could experience both individuality and unity simultaneously. Perhaps our transhuman descendants will find a way to do this.

But there is a deeper problem here. And that is that we simply don’t possess the intellectual wherewithal to answer these questions. Life remains a mystery despite our best efforts to understand. We must live without answers to many of our queries. In the meantime we should accept whatever relationships we can have with others and be thankful we have them. Without them life is very lonely.

May 26, 2021

The Next 500 Years: Engineering Life to Reach New Worlds

[image error]

A colleague recently introduced me to Christopher Mason‘s new book, The Next 500 Years: Engineering Life to Reach New Worlds.

[image error]

Mason begins,

The fundamental thesis of this book is that the same innate, biological capacities of ingenuity and creation that have enabled humans to build rockets to reach other planets will also be needed for designing and engineering the organisms that will sustainably inhabit those planets.

The missions to other planets, as well as ideas for planetary-scale engineering, are a necessary duty for humanity and a logical consequence of our unique cognitive and technological capabilities. … As far as we know, humans alone possess an awareness of the possibility of our entire species extinction and of the Earth’s finite rife span. Thus, we are the only ones who can actively assess the risks of (and prevent) extinction, not only for ourselves but for all other organisms as well. This is unusual. Most duties in life are chosen, yet there is one that is not. “Extinction awareness”—and the need to avoid extinction—is the only duty that is activated the moment it is understood.

This gives us an awesome responsibility, power, and opportunity to become the universe’s shepherds and guardians of all life-forms—quite literally a duty to the universe—to preserve life. … This duty is not only for us, but for any species or entities who can engineer themselves to avoid the end of the universe. Even if our species does not survive, this duty is passed on to the next sentience, which will undoubtedly arise.

According to Mason, since the earth cannot survive the death of our sun, we must journey to the stars to have any chance of fulfilling our duty to preserve life. And this implies we will eventually have to engineer life in order to survive on other worlds. We must direct and engineer life or we will not survive. Mason hopes that we can begin by sending genetically engineered humans to establish an outpost on Mars and perhaps launch beyond our solar system by 2500. Eventually, our descendants will have to alter the structure of the universe itself to ensure the survival of life.

Mason’s proposals follow from what he calls “deontogenic ethics,” which is based on the following assumptions: 1) only some species or entities have an awareness of extinction; 2) existence is essential for any other goal/idea to be accomplished; thus 3) to accomplish any goal or idea, sentient species need to ensure their own existence and that of all other species that enable their survival.

This further implies, according to Mason, that “any act that consciously preserves the existence of life’s molecules (currently nucleic acid-based) across time is ethical. Anything that does not is unethical. Thus, preserving the existence of life is the highest duty …”

Brief Reflections

Any reader of this blog knows that I agree we should do our best to avoid destroying ourselves or being destroyed by one of many existential risks. And I believe wholeheartedly that we must enhance our moral and intellectual nature. Leaving the planet at some point will thus be necessary and only enhanced beings will have much chance of survival then.While I do share worries about the potential pitfalls of using technology to enhance and transform human beings, I have fewer worries than most. I certainly understand that AI, robotics, genetic engineering, nanotechnology, etc. may lead to some terrible outcomes but from my point of view, we are in the position of a football team that needs to make a “hail mary” pass. I have no idea if I’m right about this but if we don’t act dramatically then something will destroy us and soon—pandemics, asteroids, nuclear war, climate change, etc. We must evolve quickly and radically to have any chance of survival.Still, proceeding recklessly may bring about some kind of unimaginable hell, so we should be careful, but I really think our situation is so desperate that we must take big risks. Certainly, if we do nothing we are doomed. The chances we destroy ourselves are great—Martin Rees thinks it’s about 50/50 in the next 100 years—that I think we need to take chances. Perhaps I’m too reckless or my former career as a poker player is influencing me too much. But there is no risk-free way to proceed and our survival depends on making dramatic changes to the nature we inherited from millions of years of evolution. At any rate, surviving and flourishing aren’t possible unless we enhance ourselves. About that, I am fairly certain.Regarding deontogenic ethics, I’d only object that survival is a necessary but not a sufficient condition in my ethics. There are fates worse than death. Perhaps I’m too sensitive to human suffering or I’ve read too much Schopenhauer but I sometimes wonder if it would be better if we went extinct. (And I’ve had a wonderful life.) I don’t say this lightly, nor to parade some pessimistic romantic sensibilities, but rather to acknowledge that the true horror of human existence can make you wonder if life is worth it.To sum up, while I certainly want sentience to survive and flourish, I wouldn’t say that survival is an absolute duty since, again, there are fates worse than death, both for individuals and species. So I disagree that anything that preserves life is good and anything that doesn’t is bad. That’s too strong of a claim. That’s why I’m a proponent of voluntary active euthanasia for human beings. (Cows, pigs, chickens, fish, etc., if they had the ability, should have chosen extinction long ago. Perhaps all non-human animals would be better off dead. Perhaps human beings too.)I hope our posthuman descendants survive and flourish but if a living hell awaits us, then I hope no sentient beings are a part of that. Here’s to hoping that sentience lives long and prospers. Still …

But as for certain truth, no man has known it,

Nor shall he know it, neither of the gods

Nor yet of all the things of which I speak.

For even if by chance he were to utter

The final truth, he would himself not know it:

For all is but a woven web of guesses. ~ Xenophanes

May 23, 2021

Sagan: The Universe Isn’t Made For Us

Carl Sagan (1934–1996) is one of my intellectual heroes. I first encountered his work in 1980 watching the 13-part PBS mini-series “Cosmos.” While I had taken many college science courses before that, there was something special about his presentation that excited me, especially his poetic, philosophical monologues. (I’ve written before about the “pale blue dot,” “on human survival,” and “science as a candle in the dark.”)

Today I rewatched the moving video above. Below is a brief recap and the full text.

Sagan begins by noting how pre-scientific cosmologies arise from our early experience. But “then science came along and taught us that we are not the measure of all things.” But Sagan wants the truth science gives not illusory comfort of religion. And today we should no longer believe “that the Universe was made for us … We long to be here for a purpose, even though, despite much self-deception, none is evident.”

But this doesn’t have to lead to pessimism because “we find ourselves on the threshold of a vast and awesome Universe that utterly dwarfs—in time, in space, and in potential—the tidy anthropocentric proscenium of our ancestors.” There is no need then to regret that we weren’t placed in a garden made for us but in which we were supposed to remain ignorant. Instead, we can use our minds to discover what is really true about the universe and where we want to go in it.

What then is the meaning of our lives?

The significance of our lives and our fragile planet is then determined only by our own wisdom and courage. We are the custodians of life’s meaning. We long for a Parent to care for us, to forgive us our errors, to save us from our childish mistakes. But knowledge is preferable to ignorance. Better by far to embrace the hard truth than a reassuring fable.

If we crave some cosmic purpose, then let us find ourselves a worthy goal.

For those interested, here is the full text:

Our ancestors understood origins by extrapolating from their own experience. How else could they have done it? So the Universe was hatched from a cosmic egg, or conceived in the sexual congress of a mother god and a father god, or was a kind of product of the Creator’s workshop—perhaps the latest of many flawed attempts. And the Universe was not much bigger than we see, and not much older than our written or oral records, and nowhere very different from places that we know.

We’ve tended in our cosmologies to make things familiar. Despite all our best efforts, we’ve not been very inventive. In the West, Heaven is placid and fluffy, and Hell is like the inside of a volcano. In many stories, both realms are governed by dominance hierarchies headed by gods or devils. Monotheists talked about the king of kings. In every culture we imagined something like our own political system running the Universe. Few found the similarity suspicious.

Then science came along and taught us that we are not the measure of all things, that there are wonders unimagined, that the Universe is not obliged to conform to what we consider comfortable or plausible. We have learned something about the idiosyncratic nature of our common sense. Science has carried human self-consciousness to a higher level. This is surely a rite of passage, a step towards maturity. It contrasts starkly with the childishness and narcissism of our pre-Copernican notions.

And, again, if we’re not important, not central, not the apple of God’s eye, what is implied for our theologically based moral codes? The discovery of our true bearings in the Cosmos was resisted for so long and to such a degree that many traces of the debate remain, sometimes with the motives of the geocentrists laid bare.

What do we really want from philosophy and religion? Palliatives? Therapy? Comfort? Do we want reassuring fables or an understanding of our actual circumstances? Dismay that the Universe does not conform to our preferences seems childish. You might think that grown-ups would be ashamed to put such disappointments into print. The fashionable way of doing this is not to blame the Universe—which seems truly pointless—but rather to blame the means by which we know the Universe, namely science.

Science has taught us that, because we have a talent for deceiving ourselves, subjectivity may not freely reign.

Its conclusions derive from the interrogation of Nature, and are not in all cases predesigned to satisfy our wants.

We recognize that even revered religious leaders, the products of their time as we are of ours, may have made mistakes. Religions contradict one another on small matters, such as whether we should put on a hat or take one off on entering a house of worship, or whether we should eat beef and eschew pork or the other way around, all the way to the most central issues, such as whether there are no gods, one God, or many gods.

If you lived two or three millennia ago, there was no shame in holding that the Universe was made for us. It was an appealing thesis consistent with everything we knew; it was what the most learned among us taught without qualification. But we have found out much since then. Defending such a position today amounts to willful disregard of the evidence, and a flight from self-knowledge.

We long to be here for a purpose, even though, despite much self-deception, none is evident.

Our time is burdened under the cumulative weight of successive debunkings of our conceits: We’re Johnny-come-latelies. We live in the cosmic boondocks. We emerged from microbes and muck. Apes are our cousins. Our thoughts and feelings are not fully under our own control. There may be much smarter and very different beings elsewhere. And on top of all this, we’re making a mess of our planet and becoming a danger to ourselves.

The trapdoor beneath our feet swings open. We find ourselves in bottomless free fall. We are lost in a great darkness, and there’s no one to send out a search party. Given so harsh a reality, of course we’re tempted to shut our eyes and pretend that we’re safe and snug at home, that the fall is only a bad dream.

Once we overcome our fear of being tiny, we find ourselves on the threshold of a vast and awesome Universe that utterly dwarfs—in time, in space, and in potential—the tidy anthropocentric proscenium of our ancestors. We gaze across billions of light-years of space to view the Universe shortly after the Big Bang, and plumb the fine structure of matter. We peer down into the core of our planet, and the blazing interior of our star. We read the genetic language in which is written the diverse skills and propensities of every being on Earth. We uncover hidden chapters in the record of our own origins, and with some anguish better understand our nature and prospects. We invent and refine agriculture, without which almost all of us would starve to death. We create medicines and vaccines that save the lives of billions. We communicate at the speed of light, and whip around the Earth in an hour and a half. We have sent dozens of ships to more than seventy worlds, and four spacecraft to the stars.

To our ancestors there was much in Nature to be afraid of—lightning, storms, earthquakes, volcanos, plagues, drought, long winters. Religions arose in part as attempts to propitiate and control, if not much to understand, the disorderly aspect of Nature.

How much more satisfying had we been placed in a garden custom-made for us, its other occupants put there for us to use as we saw fit. There is a celebrated story in the Western tradition like this, except that not quite everything was there for us. There was one particular tree of which we were not to partake, a tree of knowledge. Knowledge and understanding and wisdom were forbidden to us in this story. We were to be kept ignorant. But we couldn’t help ourselves. We were starving for knowledge—created hungry, you might say. This was the origin of all our troubles. In particular, it is why we no longer live in a garden: We found out too much. So long as we were incurious and obedient, I imagine, we could console ourselves with our importance and centrality, and tell ourselves that we were the reason the Universe was made. As we began to indulge our curiosity, though, to explore, to learn how the Universe really is, we expelled ourselves from Eden. Angels with a flaming sword were set as sentries at the gates of Paradise to bar our return. The gardeners became exiles and wanderers. Occasionally we mourn that lost world, but that, it seems to me, is maudlin and sentimental. We could not happily have remained ignorant forever.

There is in this Universe much of what seems to be design.

But instead, we repeatedly discover that natural processes—collisional selection of worlds, say, or natural selection of gene pools, or even the convection pattern in a pot of boiling water—can extract order out of chaos, and deceive us into deducing purpose where there is none.

The significance of our lives and our fragile planet is then determined only by our own wisdom and courage. We are the custodians of life’s meaning. We long for a Parent to care for us, to forgive us our errors, to save us from our childish mistakes. But knowledge is preferable to ignorance. Better by far to embrace the hard truth than a reassuring fable.

If we crave some cosmic purpose, then let us find ourselves a worthy goal.