Review of Michael Ruse’s “A Philosopher Looks At Human Beings

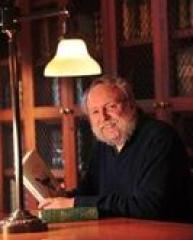

Michael Ruse (1940 – ) is one of the world’s most important living philosophers. He currently holds the Lucyle T. Werkmeister Professor and is Director of History of Philosophy and Science Program at Florida State University. He is the author of more than 50 books, a former Guggenheim Fellow and Gifford Lecturer, a Fellow of both the Royal Society of Canada and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and a Bertrand Russell Society award winner for his dedication to science and reason. He has also received four honorary degrees.

Ruse’s newest book A Philosopher Looks at Human Beings so captivated me that I finished it in a few days. The prose is carefully and conscientiously crafted with a graceful literary style that treats complex concepts with clarity and brevity. Sometimes with one-word sentences. Oneword. And so funny! Whitehead’s process philosophy “must have St. Augustine revolving rapidly in his grave.” And discussing the pangs of moral conscience that follow from marking up library books–which is funny in itself–he writes,

God help the library books because apparently Darwin won’t. You’ll be sorry. Sleepless nights, wracked by conscience at that yellow highlighting of the Critique or Pure Reason. How could you destroy the joy of others as they set out, all pure and innocent and eager, into The Transcendental Analytic to find the Metaphysical Deduction has been marked up like a copy-editor’s proof.

Hilarious. If you ever tried to read Kant … well, it’s not a joyful experience. The pages of my old copy are brittle from long ago tears.

Ruse does assume his readers have some background in philosophy. He writes “better Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied” or “existence precedes essence” or “Popperian” without explanation. But this is not problematic. Such examples are rare and almost always self-explanatory. If not there’s always google.

A Brief Synopsis – With my commentary in [brackets.]

Ruse wants to know if human beings are justified in thinking themselves special. The answer to this question comes from science, specifically from evolutionary biology. Moreover, his discussion will lead to moral questions such as, what should we do and why should we do it? Again evolutionary biology provides the most important insights. I agree. We can’t talk intelligently about human nature or ethics without an understanding of our evolutionary past.

The first chapter distinguishes between a)religious; b)secular; and c)creationists views of human nature. It’s important to note that his small (c) creationists are NOT biblical literalists. Instead, they are those who think “human nature is … created not discovered.” They think that we are special because “we have the ability to make ourselves special.” [If we are indeed special because we can improve our nature then, as a transhumanist, I ask “why not follow this evolutionary thinking to its logical conclusion? Why not transcend our nature? Don’t we have a moral obligation to make ourselves more special?]

For Ruse, Sartre exemplifies small (c) creationism. Quoting Sartre,

God does not exist, yet there is still a being in whom existence precedes essence, a being which exists before being defined by any concept, and this being is man or, as Heidegger puts it, human reality. That means that man first exists, encounters himself and emerges in the world, to be defined afterwards. Thus, there is no human nature, since there is no God to conceive it. It is man who conceives himself, who propels himself towards existence …

[The transhumanism here is implicit. If we define ourselves, if we conceive ourselves, then let’s use every means available to do that. Remember that we call our human nature is not static, it simply refers to our current stage of evolutionary development.] Ruse argues then that it isn’t God or nature that makes us special—if indeed we are special—rather that is a judgment we make about ourselves. We are nothing more or less than what we have made of ourselves. [Agreed. So let’s make more of ourselves.]

There is a lot to say about the intervening chapters but let me outline the logic that leads to the book’s conclusions so as not to provide too many spoilers.

If science is the key to answering questions about our nature then “we must dig into the underlying metaphysical presumptions that people bring to their science.” This is the subject matter of the second chapter. Here he introduces the distinction between organicism and mechanism—the two metaphysical assumptions brought to science. Roughly speaking, some people think that the world is an organism and that humans have a natural value because they are the most special part of this world (or of the creation for the religious.) Others think that the world is a machine and that we must make our own value judgments, including judgments about ourselves.

Next, in Chapter 3, he turns to Darwinian evolutionary theory which explains human nature. [This should be obvious but many philosophers, particularly religious ones, use a 2,500-year-old version of human nature in their philosophy.] Chapters 4 & 5 evaluate Darwinian claims about human nature in light of the metaphysical assumptions discussed in Chapter 2. In Chapter 6 Ruse considers the question of progress, to see if organicism and mechanism reach different conclusions. In the last 2 chapters, he compares the views of organicism and mechanism in the moral realm.

The epilogue looks at the moral realm, “as seen through the lenses and demands of the three groups of the first chapter—the religious, the secular, the creationist?” Ruse defends small (c) creationism, what he calls Darwinian existentialism—we create our own values, we create our own meaning.

However, this does not imply naive moral relativism. For we are social, we are part of a group and our ancestors found rules of behavior that worked—we all do better if we all cooperate; we benefit from reciprocity. We get our morality from our evolved human nature along with cultural influences. There is no higher standard than that.

What then makes humans special? Ruse concludes,

As a Darwinian existentialist, I ask for no more than I have. As a Darwinian existentialist, I want no more than I have. I am so privileged to have had the gift of life and the abilities and the possibilities to make full use of it.

I am moved by Ruse’s humble gratitude for the chance to have lived, and in his case, to have lived well-lived. But he can do all this and take a final step. Let me explain.

E.O. Wilson wrote,

The human species can change its own nature. What will it choose? Will it remain the same, teetering on a jerrybuilt foundation of partly obsolete Ice-Age adaptations? Or will it press toward still higher intelligence and creativity …

Now consider Ruse’s creationism (c), standing on our own, looking within, Darwinian existentialism. I agree but with a major caveat. I do ask for more and I do want more. Not just for myself but for others. For all of us, I want more consciousness, more justice, more joy, more life.

I believe that Ruse’s evolutionary perspective, his emphasis on creating our own meaning and values leads naturally to transhumanism. If “it is having to stand on your own … that makes humans of great worth” then we really stand on our own, really create ourselves if we transcend our current nature. Why be content with our current nature? Why not direct evolution?

Yes, this is risky, but with no risk-free way to proceed, we either evolve or we will die. We know what we are, but we know not what we may become. Or, as Nietzsche put it “What is great in man is that he is a bridge and not a goal…” Nietzsche wasn’t on board with all this “humans are so great stuff.” I’m not either. I’m no angel, just a modified monkey who was lucky to have great parents, a middle-class lifestyle, a good education, and a job where I received free exam copies of Michael Ruse books!

So transhumanism complements Ruse’s evolutionary vision. Once you adopt an evolutionary perspective, and Ruse is one of the world’s more ardent defenders of the truth of Darwinism, then you should look not just to the past and present but to the future. Ruse is a philosopher looking at human beings as they are now. His analysis is spot on. But taking an evolutionary perspective, I’m more interested in what we might become. What can we make of ourselves?

I do know this. If we survive and prosper, our descendants will come to resemble us about as much as we do the amino acids from which we sprang. Surely this is something for any evolutionist to ponder.

________________________________________________________________________

I’d like to thank Professor Ruse for writing his book. I’ve read many of his works over the years and have always enjoyed them. (I previously reviewed his A Meaning to Life.)