Mark Winne's Blog, page 8

December 2, 2018

Stand Together or Starve Alone Goes Rogue!

Stand Together or Starve Alone is now available for $30 direct from the author (learn more about the book at www.markwinne.com). Act now because this offer decomposes at midnight December 31, 2018. See below for details and reasoning:

We’re breaking the rules

To celebrate the yules;

No cards, no banks,

No gimmicks, no thanks!

Straight from the source,

Winne a Gift Horse?

At $30 a book, with shipping

To boot!

He must be a kook!

Amazon, Paypal, ABC-CLIO,

Nothing you do is ever for real.

Your deals are lame,

They put you to shame

$46 a book!

You gotta be some kind of crook.

Chuck the Zuck,

Bye-bye Bezos,

Say, “WTF!”

Tempt the Cosmos!

No chip readers,

No lost leaders,

We’re going direct!

Say, “what the heck!”

Send me a check;

Who needs Fedex!

Just leave it to me

And Santa’s helpers,

The U.S.P.S.

And all us self-helpers.

No muss, no fuss,

No Elon Musk.

Without the trust,

It’s all a bust!

From the highest Steeple

Straight to the People!

Winne’s off his tether,

Buy Stand Together!

To order and receive your signed copy of Stand Together or Starve Alone, send a check for $30.00 per book made out to “Mark Winne.” Mailing address: 15 Cerrado Loop, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87508.

To receive by Christmas, your order must arrive by December 15. To receive at all, orders must be received by midnight on December 31. Please specify the name of the person to whom the book should be signed. Remember, a signed copy is immediately worth 10 cents more than you paid for it! And because I feel sorry for the shabby way our President treats Canada, it’s the same price (including shipping) for Canadians.

PS All purchasers are automatically entitled to the must-have bumper sticker of the year: “Stand Together or Starve Alone” made of structural paper and capable of securing sagging bumpers to rusty vehicles.

November 18, 2018

Taking Care of Our Own

Wherever this flag is flown…w e take care of our own.

– Bruce Springsteen

When it comes to food and farming, there’s been an assumption since the planting of the first seed that the harvest first feeds the farmer, the family, the clan, then the community. We’ve strayed from that simple but necessary notion over the past decades as our food system has tilted in the direction of industrial scale production and distribution that serves global markets first. Where once the people’s voices and nutritional requirements called the tune, local food needs and connections are drowned out by market forces that dance to a different beat.

In the midst of the post-World War II tectonic shifts in the ways we grow and get food, domestic hunger persists, a fact that achieves a seasonal acuity during these holiday months. One in eight people and one in six children are food insecure according to the USDA. Obesity and diabetes rates are two to three times higher than they were in 1992. Most 2-year-olds today will develop obesity by age 35, according to a recent project of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

What’s become obvious is that the ethical commitment of a local food system to first take care of its own has been displaced by a global food system’s commitment to first take care of its bottom line. Just as a prosperous civilization that fails to meet the needs of the least among us cannot lay claim to a moral place in the universe, our food industrial complex cannot profess to “feeding the world” when millions of its own are food insecure or in the throes of diet-related disease. Likewise, chemically-based, energy-intensive, carelessly polluting methods of food production display a willful disregard for our children and grandchildren who will suffer mightily from a degraded environment and global warming.

Though our food system has veered recklessly from the intimate to the distant, the people’s urge to be heard and to shape their own destiny has never diminished. The revival of farmers’ markets over the past 40 years, the growing awareness of sustainable agriculture and healthy eating, and the rise in thousands of feeding initiatives attest to our refusal to accept so-called economic norms. As if to say, “there must be a better way,” consumers, farmers, and those who advocate for good food for all are raising their voices in Congress, state legislatures, and city councils.

No better evidence of this can be found than in the emergence of local and state food policy councils, which according to the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future number over 250 nationwide. Here we find producers, anti-hunger advocates, chefs, and government officials, just to name a few stakeholders, coming together to plan for their communities’ food future and to ensure that those plans are implemented.

While food policy councils come in different shapes and sizes, they generally serve as the eyes and ears of the community and its policy makers. They are not comprised of ranters-and-ravers and soap box standers. They are made up of thinkers and doers who aren’t afraid to roll up their sleeves and work with people of different opinions and interests for the common good of their community.

And much good has come from food policy councils. In New Mexico, they have enlisted state government to start a permanent farm to school program that is using the buying power of public schools to purchase New Mexico-grown food. In Minnesota and Connecticut, they have worked with transportation officials to establish new bus routes to ensure that people who don’t own cars are able to reach a grocery store. In Colorado and Massachusetts, they have worked with farmers’ markets and state agencies to enable the use of SNAP benefits at farmers’ markets. In Kansas, they paved the way for the establishment of a food hub that connects the state’s growers to better market opportunities.

While no single local or state food program or policy will grind the gears of the global food system to a halt, they do refocus our attention on a place – our place – and a people – our people. This is exactly what they are starting to do in Nebraska with the establishment of the Nebraska Food Council. With guidance from the Center for Rural Affairs, people from across the state have been meeting to reset Nebraska’s food compass so that its needle points in the direction of its people – the food they eat, the air they breathe, and the water they drink.

At this time, food policy councils and numerous local food coalitions are loading their carts with programs and policies that move with muscle and purpose to the checkout line. A quick scan of what they have selected and set in motion includes strengthening and expanding farm to school initiatives which now exist in 47,000 public schools; changing regulations and providing funds to support more local food hubs and food businesses; expanding programs to increase the use of SNAP benefits at the nation’s 8,500 farmers’ markets; protecting access to farmland for all those who want to produce food; and kicking ass and taking names to ensure that all our fed.

This is only a partial list of what food activists across the country are doing to secure a healthy and sustainable food system for all. As citizens of a democracy, we must raise our voices for what we believe is right; as members of a community, we must take care of our own.

I can’t think of a better way to celebrate Thanksgiving!

October 1, 2018

Welcome to the Era of the Lockdown

In the early 1950s, Mr. and Mrs. Winne moved themselves and their two young boys to the north Jersey town of Ridgewood, located just 20 miles west of New York City. Besides being within easy commuting distance of Manhattan’s corporate headquarters where Mr. Winne, the up-and-coming executive would work, my parents chose Ridgewood for the quality of its schools, allegedly the best in the state. My brother and I, later balanced by the addition of two sisters, would find nothing about our education to dispel that assumption. We all went on to college as did 85 percent of the 600 people in my 1968 graduating class of Ridgewood High School.

The realization of just how privileged I was came rushing back to me this September when 150 or so members of the RHS Class of ’68 gathered for a reunion. The highlight was a school tour led by the vice principal and several very sharp junior and senior students. This VP was a decidedly different breed of cat from the one who patrolled the corridors with an iron fist in my day. Instead of busting into smoke-filled boys’ rooms to round up the miscreants, this one was conversant with the latest educational methods that included an open campus, student phone apps, and swipe cards that securely let students and staff into the school. Yet, in spite of what the students told us about Ridgewood’s 100-plus clubs and activities, frequent field trips abroad, and what is now a 93 percent college entrance rate, the threat of violence stalked the hallways in ways that it never did in my day.

Peeling off from our tour group to use the nearest restroom, I came across this sign stuck to the wall next to the toilet:

Ridgewood Public Schools Bathroom Lockdown Instructions

Remain Calm

Remain Quiet

Lock Yourself In A Stall

Pull Your Feet Up Higher Than The Stall Wall

Wait For An Announcement That The Lockdown Is Over

My God, I asked, is this what kids today have to prepare for? As a teenager I can recall filing into the school basement and being told to sit on the concrete floor and place my hands on my head, as if that would protect me from an all-out Soviet nuclear attack. One difference between then and now is that our civil defense drills were primarily designed to reinforce our loyalty to the fabricated logic of the Cold War and the military industrial complex. My fears then were grounded in a strategic global paranoia, while today’s Ridgewood students – and most assuredly those of Columbine, Sandy Hook, and Parkland – are founded on their lived reality of a deranged classmate taking them out with an NRA-approved assault weapon. Francesca, my group’s student tour guide, told us that over half of RHS’s students participated in last February’s walkout held in sympathy for the Parkland victims and support for the emerging student anti-gun advocates.

High school reunions are meant to be celebrational, a happy affirmation of our shared youth and prosperous adulthoods which for many of us now included a comfortable retirement. But the evening’s dinner and dance, though filled with sweet remembrances and some less-than-sexy boogying, commenced with a stark reminder of the injustices that our privilege allowed us to escape. The oh-so-white Class of ’68 had a total of 9 members of color. When a long moment of silence accompanied the reading of the names of our deceased classmates, I realized that 4 of those 9 were among them, even though the total death rate for the class was only 5 percent. Statistically significant? I’m not sure. But meaningful? I think so.

A few days later I found myself in Jacksonville, Florida where I was researching my next book. Jacksonville is Florida’s most populous city and the nation’s largest by land area. Nearly one-third of the residents are African-American and about 60 percent are white. I’m driving through the city’s vast Northside that is largely black and lower income – and mostly one massive food desert – but filled with amazing people and projects that are trying to bring health and affordable food to the area. One of those people is Ju’ Coby Pittman who is the CEO of the Clara White Mission, an award-winning nonprofit that serves Jacksonville’s homeless and veterans with numerous programs including a culinary arts training program and a 14-acre community farm. Another recognition was bestowed on Ju’Coby just this July when she was appointed by Florida governor Rick Scott to fill a Jacksonville City Council seat vacated by a former city councilperson who is now under Federal indictment for fraud and corruption.

My rental car’s outside thermometer reads 94 degrees, its humid, and my AC is not keeping up. I pull into the farm and pass a couple of acres of nicely tended greens and beans before I find Ju’Coby waiting for me in her much better air-conditioned vehicle. Since the farm has yet to build an office – a recent city grant will improve the farm’s infrastructure – we converse in her car for over an hour. While she’s optimistic about the progress the farm is making toward becoming a major source of fresh produce for the neighboring community, she was extremely distressed by her first 74 days as the city councilwoman for the surrounding 8th District. “I was shocked by what I heard from some teenagers I met in school,” she tells me. “One of them said, ‘We can buy guns like ‘tater chips. I need to carry a gun to protect myself and to get respect.’” She went on to relate a conversation with a teenage girl who told her, “I can’t get help from my mama because she has the same problems I do.” If those conversations weren’t enough, one of her tours took her to the city morgue where she found four dead black teenage boys. Ju’Coby was down, but not out, telling me, “There’s a lot more good around here than bad.”

I believed her and the others I met who are fighting to keep their children out of the morgue. I believed the Ridgewood High School vice principal who told us alums how school officials are keeping this beautiful school safe for the joyful pursuit of learning. And I believed that the hearts and minds of my classmates were stung by the disproportionate loss of their classmates of color. Here’s to justice and safety for all! May that dream one day come true.

September 9, 2018

Fifty Years Before The Mast

It hit me the other day like a ton of turnips that September marks the 50th year of my doing something. Doing what? Well, anything that really matters, I guess. Fifty years ago, I was 18, and during those early years I wasn’t much more than a tub of self-absorbed protoplasm brought to an occasional boil by increasing doses of testosterone. Nothing mattered, except, of course, me.

At the beginning of my freshman college year, the universe sent me a message that slammed me against the wall with as much force as an angry cop. It shook me loose from my bourgeois moorings, seared my khakis-clad butt with the blistering fires of Hell, and seized me by my windpipe. The thing was famine. Not mine, of course – my dining hall meal card was quite ample – but the famine of children in Africa whose protruding ribs and fly-encrusted eyes stared pleadingly back at me from the pages of Time magazine.

That was all the horror this suburban Jersey boy needed to set sail for somewhere that mattered. After spending that first fall at college raising awareness and money for famine relief, I would stay the course for the next 50 years. Sometimes I found my way with ease from port to port and project to project, and other times I became hopelessly lost in a fogbank of words, ideas, and problems with no apparent causes. I would learn early that situations I thought were obvious and clear-cut often were not.

Take famine, a problem with an obvious and immediate solution. People are hungry and there’s no food. Get money, buy food, and give it to them. While my early instincts were correct – shock followed by an urgent need to respond – my analysis of the situation was faulty. The cause of the famine was political; a raging civil war fueled in part by tribalism, the vestiges of colonial oppression, and economic interests often centered around oil had left millions of innocent people cut off from food. This analysis would be reinforced many years later after reading Tombstone by Yang Jisheng who chronicled the politically inspired 1958-62 Chinese famine in which 30 million people perished.

Not only would more thoughtful analyses alter my response to food problems over the course of my career, they would also alter the language, terms, and ensuing organizational factions (see my book Stand Together or Starve Alone). Famine would later give way and diverge at the domestic U.S. level to hunger, then food insecurity, food banking, emergency food, community food security, obesity, food deserts and access, and variations on food, social, and racial justice and equity. Each iteration came to me with its own learning curve, some steeper than others depending on how long I had been immersed in earlier iterations.

In my more open-minded moments, I would try to view the rapidly changing food movement landscape as a continuous learning opportunity. But in reality, experience was always my guide. Like the spider in the Walt Whitman poem that explores its “vacant vast surrounding” by casting out filaments to find its way one strand at a time, I was marking a path across

…measureless oceans of space,

Ceaselessly musing, venturing, throwing, seeking the

spheres to connect them,

Till the bridge you will need be form’d…

Till the gossamer thread you fling catch somewhere….

My learning was always inductive, a web of dots assembled one at a time until a grand mosaic started to emerge. It didn’t mean that the food movement wasn’t always lobbing theories my way – often with so little in the way of experiential underpinnings that they were of dubious value. These included shimmering concepts, often sporting an academic gloss, that wowed you for a while but would ultimately leave you empty and yearning for a juicy cheeseburger. And then there were those concepts that arrived with no sense of history, no reference to what preceded them, bearing facts that were often distorted.

A recently discovered Wikipedia entry concerning the food justice movement is one illustration of historical distortion cloaked in half-truths. It reads, “The modern Food Justice movement grew out of the Community Food Security Coalition in 1996. [I]t was composed entirely of white Americans, and accepted little input from residents of the food insecure areas [it] was trying to support. It emphasized the consumption of local fresh fruits and vegetables, and removed race from the conversation.”

The first part of the statement is largely correct, though lacking in at least 30 years of historical context like anti-hunger work and community gardening which preceded CFSC. The references with respect to race, however, are blatantly false. I worry like everyone else today that we simply don’t understand the power of our words, those spoken and unspoken, truthful or not, to send the world off its rails. “How great a forest is set ablaze by a small fire! And the tongue is a fire,” reads the Letter of James 3 (New Testament). And when today’s harsh words and distortions use the internet as their accelerant, a conflagration can easily ensue.

As I have grappled with evolving concepts like food justice and tried to gaze at life through today’s ubiquitous “equity lens,” I remind myself that each generation has “its own way of walkin’, its own way of talkin’.” The filaments they cast and the bridges they build will look differently from the ones I slogged across. Their own constellation of thoughts, experiences, and even voices distilled from the academy will enable them to navigate their own seas.

But I did learn one new thing this summer coincident to my 50th anniversary. I cast my filament onto the shores of southeast Alaska where I spent time researching Sitka’s food system. During the course of many interviews I was advised by both the Native Alaskans and non-Native to heed the wisdom of the Tlingit elders. This was not some weird voodoo thing that Anglo’s like me view with quiet skepticism, but a form of traditional local knowledge that draws its strength from a spiritual connection to the natural world. It also rests upon the simple power of observations toted up over one’s lifetime and passed on to the next generation and the next. For them, the immediate context was this year’s declining salmon and herring runs which were the worst in the elders’ memories, memories that collectively spanned hundreds of years. For the Native Alaskans who depend on these traditional foods, the consequences are potentially dire; for the rest of us their observations suggest that climate change and overfishing may take us all down the road to ruin. Now that I’m technically an elder, or at least elderly, I can empathize with the need to respect that wisdom.

Finding the things that matter has been a beautiful journey. Understanding their meanings is a lifetime pursuit.

June 6, 2018

Summer and Fall Appearances – 2018

I’m fortunate to be participating in some awesome training and learning opportunities this coming summer and fall. My travels will take me to amazing “repeat” states – Alaska! – as well as one of the two states I’ve never been to – South Dakota! I’ll let you guess which is the 50th state that remains on my bucket list. I’m also excited to be attending my high school reunion (not saying which one) in New Jersey. I’ve included that trip down memory lane just in case there’s anyone in the Northeast who wants to do a little business while I’m in the neighborhood, and when not otherwise reminiscing with former classmates.

The purposes of my visits vary from giving keynotes, to conducting workshops, to doing research. What’s unusual is that I’m promoting one book, Stand Together or Starve Alone, at the same time I’m researching another book, tentatively titled Food Town, USA. Stand Together is moving rapidly out of warehouses and off the shelves into good, loving homes and offices across America. Don’t get caught short – order yours today! Wanna make a deal? I’m all ears! As the radio ad from “Little Lenny’s Discount City” just off Route 17 in North Jersey used to say, “Money talks, nobody walks!”

Buy from the publisher: http://abc-clio.com/ABC-CLIOCorporate/product.aspx?pc=A5085C

Where I’ll be (check for updates and be in touch if you’re looking for a little help):

Sitka, Alaska – July 6 – 13. I’ll be visiting what may be America’s best little food town for research, but I’ll also be speaking at the Sitka Public Library on July 10 at 6:00 PM. Contact Charles Bingham at charleswbingham3@gmail.com for more information.

Baltimore, Maryland – July 16 – 18. I’ll be working with the Center for a Livable Future at Johns Hopkins University. I’ll be performing live daily with the Food Policy Network’s All-Star Advisory Committee Band.

Ridgewood, New Jersey – September 21 -22. The author returns to the place where it all began for him. Surely, the talk on the dance floor will be something like, “And I sat next to him in junior English!”

South Dakota – October 31 – November 2. Yes, this is the 49th state that I’ll be visiting for a work-related activity (#50 is just across the border). I’ll be speaking at South Dakota State (contact Brett Owens at brett.ownes@sdstate.edu) and at the South Dakota Local Foods Conference (contact hollyt@dakotarural.org).

Spokane, Washington – November 13. I’ll be speaking at the Spokane, Washington food summit. For more information contact Nathan Calene at ncalene@spokanecity.org.

Nebraska – I’ll be working with the newly formed Nebraska Food Policy Council some time late this fall. Stay tuned or be in touch with the Center for Rural Affairs.

May 20, 2018

Stand Together for Community Food Projects

Want to encourage people to eat healthier? Don’t do one thing, do many things – new supermarkets, food education, calorie labeling. Want to make a community healthier and more food secure? The use of multiple interventions also applies. Bring together the food system’s stakeholders, engage the community, make a plan that involves multiple approaches, and work together. Those are the purposes of USDA’s Community Food Project Grant Program (CFP), and unless Congress includes it in the upcoming Farm Bill, CFP will cease to exist. The time to take action to defend CFP and what it has done for hundreds of communities across the nation is now!

As I described at some length in my new book Stand Together or Starve Alone http://www.markwinne.com/books-by-mark-winne/ much of the national policy response to community food security, dietary health, and local food systems has come in the form of a crazy-quilt of small federal grant programs. They are “small” because their total funding is in the millions as opposed to the billions for programs like SNAP, and their focus and reach are generally narrow. While they may promote innovative approaches like farm to school or “double-up bucks” at farmers’ markets, the initiatives don’t require comprehensive strategies that engage a wide swath of the community. This is precisely what CFP is designed to do.

In Warren, a northeast Ohio community that’s been struggling to get back on its feet since the steel industry left town, the Trumbull Neighborhood Partnership used a CFP grant to conduct a food assessment. They engaged dozens of stakeholders and community members in a process that is now bringing new community gardens, farmers’ markets, and other local food activities to close the food gap in neighborhood food deserts.

Going back almost two decades, a CFP grant in Santa Fe, New Mexico brought a new farmers’ market to a lower income area of the city while also piloting an early farm to school project. Today, the State of New Mexico contributes $400,000 annually to a statewide “double-up bucks” farmers’ market program, and the Santa Fe School District allocates $50,000 a year of its own funds to buy food from the region’s farmers for its schools.

Ontario, California is the site of Huerta del Valles where, with the help of a 2016 CFP grant, hundreds of Latino families have converted three-acres of land into one of the most exciting urban agriculture projects you’ve ever seen. Greenhouses, large compost sites, dozens of family garden plots, and several commercial size garden sections have turned this community-led farm into an urban oasis. And expansion plans are underway, thanks to CFP!

These are just a few of the hundreds of community-driven projects spawned by CFP over the past 20 years. The program has so many impacts on low-income communities and family farmers across the country that its return on investment far outstrips its small annual appropriation of $9 million. In 2016 alone, CFP directly benefitted 233,000 people, 70 per cent of whom were low income. It creates wealth and jobs for small farmers and low-income community members, while stimulating new markets, generating food donations to the hungry, teaching agricultural literacy, providing job training, fostering civic engagement, and transforming communities toward greater sustainability and equity.

Just in terms of job creation alone, the program created 195 jobs in 2016, retained 157 jobs, and indirectly created another 130 jobs. To monetize this service, we can use the well-regarded figure of $30,000 that it costs to create a job. Seen in that light, CFP generated a direct value of $5.9 million. That’s quite an impressive achievement for a program that was never intended to be an employment program.

There are intangible outcomes from CFP as well. Many grantees are applying for the first time to USDA, which is never an easy process. The experience gives them the practice and confidence they need to apply for other programs. Leadership development is another consequence of participation in a CFP grant. In 2016, grantee projects created 367 new leadership roles, 70 per cent of which were filled by people of color and 38 per cent by youth. In these ways, CFP builds the capacity of organizations to secure and manage the resources they need to strengthen their own communities.

If you want to preserve the right of towns, cities, and counties to control their own food destinies, you need to let Congress know that you support CFP and they should too. If you’re not sure who to call, here’s the congressional switchboard number which can connect you to your representative and senators. Time is of the essence. Act now!

To call your Member of Congress: US Capitol Switchboard (202) 224-3121

To locate your Member on-line: U.S. House of Representatives: www.house.gov U.S. Senate: www.senate.gov

April 8, 2018

The Colfax Massacre: Lessons for Today

Five farmers are standing by the side of the road selling their goods at their farmers’ market. It turned out to be one of only two main roads in Colfax, a sleepy little central Louisiana town of 1,600 people cut neatly in half by a railroad track. Nothing too remarkable here as far as Saturday morning markets go – a small number of customers were inspecting the fall fare of collards, squashes, jams and jellies; people were chatting congenially over bushel baskets and pick-up truck beds. As Kate Littlepage, a local farmer and vocational agriculture instructor told me, “This market is less about food and more about community.”

Somewhat more noticeable, at least for this Yankee, was that two of the five farmers were African-American. My racial radar seems like it’s always on these days, but the deeper I plunge into the South, the more blips I see on my screen. It turns out that I was picking up historical signals from the very soil where I was treading. Though the Colfax farmers’ market was micro in size, its racial composition made it out-sized in symbolism. During this week 145 years ago – Easter Sunday, 1873 – over 150 black people were massacred not far from this site by a resurgent force of neo-Confederate, white supremacists that went by the name of the White League, the predecessor to the KKK. Lacking social media and phone cameras, most of America didn’t become aware of the massacre until hand-drawn illustrations appeared in Harper’s Magazine one month later.

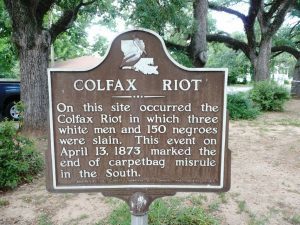

Are the days of racial bloodletting over? In 1950, the year I was born, an unrepentant Louisiana contingent with a dubious historical mission erected a marker in the vicinity of this clash. It read, “Colfax Riot – On this site occurred the Colfax Riot in which three white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April 13, 1873, marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.” It took over 50 years for a more repentant contingent to remove the marker, but it stood all that time as a potent example of the same lies and deceptive messages that are resurgent today.

Calling it a “Riot” instead of a massacre put the blame on a duly constituted, and largely black state militia that was attempting to enforce the newly acquired enfranchisement of black residents. When most of those militiamen surrendered to the heavily armed white paramilitary force, they were gunned down in cold blood. To say that the number of slain “negroes” was 150 is probably a low estimate since many of the bodies were thrown into the nearby Red River, never to be found or identified. “Carpetbag misrule” is a barely concealed Confederate-ism , not unlike “Crooked Hilary,” that undercut Reconstruction’s legitimate task of enforcing federal laws that included protecting the rights of recently freed slaves.

Calling it a “Riot” instead of a massacre put the blame on a duly constituted, and largely black state militia that was attempting to enforce the newly acquired enfranchisement of black residents. When most of those militiamen surrendered to the heavily armed white paramilitary force, they were gunned down in cold blood. To say that the number of slain “negroes” was 150 is probably a low estimate since many of the bodies were thrown into the nearby Red River, never to be found or identified. “Carpetbag misrule” is a barely concealed Confederate-ism , not unlike “Crooked Hilary,” that undercut Reconstruction’s legitimate task of enforcing federal laws that included protecting the rights of recently freed slaves.

Even in a hostile post-Confederate Louisiana, however, federal prosecutors managed to obtain convictions against three of the white attackers. But they would be thrown out by the Supreme Court (United States v. Cruikshank) in 1876 on grounds that enforcement of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments – protection of civil and voting rights – rested with the states, not the federal government. This ruling was effectively the final curtain call for the Reconstruction Era ushering onto the stage one hundred years of Jim Crow.

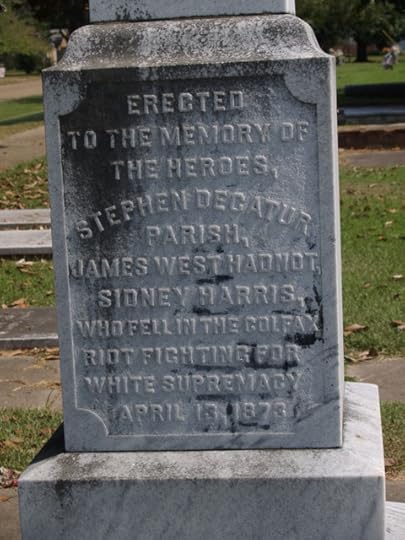

Yale history professor David Blight summarized the Colfax events with a quote in the Lafayette Advertiser (3/7/13): “Colfax is…a case of political murder. It’s murder for political reasons… That’s the kind of society we always say we’re not.” Like the My Lai massacre 50 years ago, when hundreds of Vietnamese civilians were murdered by American soldiers with only one conviction obtained – Lieutenant Calley (he received three-and-a-half years of house arrest before his sentence was commuted to time served); like African-Americans today shot by police for the flimsiest of reasons and whose killers are rarely held accountable; like white supremacists who run down innocent protestors; like this inscription to the three white men killed in the massacre on a 12-foot tall obelisk that stands today in an all-white Colfax cemetery: “In loving remembrance to the memory of the heroes Stephen Decatur Parish, James West Hadnot, Sidney Harris who fell in the Colfax riot fighting for White Supremacy.” The victims are buried and mourned by their loved ones. The perpetrators go free or are memorialized by their community.

If justice is only a dim light on a distant horizon, what do we do in the meantime? Standing by the side of the road with those farmers, not yet fully aware of the meaning of the Colfax massacre, I was reminded of the events that had led up to the opening of this market. They were described to me by James Cotton Dean, Director of Regional Innovation for the Central Louisiana Economic Development Alliance. He has worked in the area for five years, organizing community economic development projects. Dean had reached out to the Colfax community to identify low-cost ways of stimulating the local economy. On one of his first attempts, as he tells it, eight people gathered at a church one night in 2013 to discuss what could be done. Four of them were black and four were white, and each racial group sat separately on opposite sides of the room. Trust was low and the conversation was muted, moving along in fits and starts. After an hour of little or no progress, Dean suggested they take a break.

Dean is young, and at the time was new to organizing work in racially divided communities like Colfax. Worried that the whole evening might be a bust, he was pleasantly surprised when all the people returned to the room. When he asked the group, what was one thing they wanted that they didn’t have, they unanimously replied healthy food. When he followed up by asking what could be done to get healthy food, everyone landed on the idea of a farmers’ market. The rest of the evening was devoted to working out the details of what was to become the Colfax Farmers’ Market. Dean was as shocked as he was relieved when the meeting ended with everyone hugging each other.

I want to find lessons in these stories, but I know that institutional racism in America, whose roots run deep and are watered regularly by white hatred, won’t be undone by local food alone. At the same time, I don’t see a viable pathway without a table where black and white can sit down and break bread with one another. As John Dean said, “Food was something they could do together.” The farmers’ market is only a beginning, a community space, and perhaps the more monuments and markers to racism we tear down the more room we’ll have for good local food.

#StandTogether for racial justice and equality!

March 18, 2018

Surround Sound: Beating Back Obesity

“No country to date has reversed its obesity problem,” was just one of the grim pronouncements I heard at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health “Obesity and the Food System Symposium.” This statement regarding the gloomy state of our fatness was offered by Dr. Martin Bloem, the new Director of the Center for a Livable Future and formerly a Senior Nutrition Advisor at the World Food Programme. Dr. Bloem wasn’t alone in his dismal appraisal. More than a dozen of the nation’s leading obesity researchers and experts presented similar views on what is arguably America’s biggest public health crisis.

Dr. William Dietz, the public health chair at George Washington University and formerly Director of the Nutrition Division at the Center for Disease Control ran the numbers down for the 75 academics, practitioners, and students gathered on a sub-freezing March day in Baltimore. Obesity rates have climbed from 10-25 percent of the population (the range reflects differences between age, gender, and race) between 1971 and 1975 to 29-40 percent today. He went on to say that 17 percent of children between 6 and 11 years of age are obese; the vast majority will become obese adults which Dr. Dietz characterized as a “major threat to our population.” And as man of reserved academic demeanor, Dr. Dietz did not appear prone to hyperbole.

Looking to blame “Big Food” or too much screen time? Think again. The causes are complex and woven intricately into this thing we call the food system. Looking first at historical and cultural factors, we can point the finger at such post-World War II phenomena as the increasing prevalence of home appliances (e.g. rather than hanging the wash on the clothesline, we merely move it from the washer to the dryer), suburbanization and its accelerating rates of car use, the number of TVs per household, elimination of physical education and home economics in schools, the avalanche of fast food, and the shift from high-calorie burning jobs in fields and factories to the sedentary life of the office.

Yes, our culture as well as our industrial models of food production and marketing have taken their toll on the human body. With a nod to Michael Pollan, Dr. Dietz noted that young men are consuming over 600 calories of sugary soft drinks per day, stemming of course from the high-fructose corn syrup connection and our “cheap food” crop subsidies that make healthy food more expensive. But one black and white photo of a 1950 household’s food supply put the story in perspective. A smiling family of four stood in the foreground, and behind them was arrayed a typical year’s worth of what they would eat. The only processed food item amid stacks of fresh produce, dairy, and meat were several boxes of corn flakes. That’s only 68 years ago!

The marketing of unhealthy food by the food industry, especially to children, was singled out as a leading culprit. Dr. Kelly Brownell, Dean of the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University and listed by Time Magazine as one of 2006’s “100 Most Influential People,” felt a more aggressive legal strategy targeting the food industry was necessary. While he suggested something akin to the state Attorneys Generals suing Big Tobacco, others were swift to point out the legal conundrum posed by the first amendment’s guarantee of free speech, which includes advertising. It was agreed that children are unable to defend themselves against the unhealthy food marketing that is carefully calibrated to penetrate their developing brains, but Dr. Shiriki Kumanyika, professor of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine said that the public health community would have to prove that advertising’s harm to children was great enough to warrant the neutering of the food industry’s free speech rights. Given that a thousand dead children have not been enough so far to override the second amendment, it’s unlikely that millions of obese children will be enough to squelch the first amendment “rights” of MacDonald’s and Coca-Cola.

Of course, we can always hope that we can beat Big Food at its own game. Believing that enough darts of healthy food information can stick to their intended targets, we continue to look to nutrition and food education for salvation. But as Johns Hopkins Visiting Scholar, Dr. Kate Clancy pointed out, “Advertisers know more about child psychology than child psychologists,” and with their multi-million-dollar marketing budgets, Big Food is always ten moves ahead of us. Yes, we’re itching to go to war with them, but instead we’re caught in a chess match where a stalemate is the most likely outcome.

“Surround sound” is how Dr. Ross Hammond, a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institute and member of the Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academies of Science, described the approach that he and other presenters felt could stem obesity’s deadly tide. One way to prepare for such an audible assault is to first disabuse ourselves of the notion that there is one silver bullet – policy or program – that will reverse obesity. From the maxi to the mini, we often look for action items such as a major overhaul of our national crop subsidies, a sugar-sweetened beverage tax, or mega doses of nutrition education as the “one thing” we need to do. Instead, a holistic, systems-oriented framework that brings an array of interventions to bear in a coordinated fashion is what the data suggests is most desirable.

There was no lack of interventions offered at the symposium. The City of Baltimore, for instance, offers tax abatements on vacant land to promote urban farms; a beverage container tax, warning labels on sugar-sweetened beverage containers, and restrictions on carry-out food outlets (some neighborhood residents reported getting half of their daily calories from carry-out) are all part and parcel of the city’s obesity prevention efforts. Besides a sugar-sweetened beverage tax, Philadelphia has a healthy vending policy, but the increase in healthy eating associated with that policy has not been significant. Minneapolis has a staple food ordinance that requires stores to stock a minimum percentage of healthy food, but it hasn’t been easy working with retailers. SSB taxes are sprouting in cities, but the tax must be sizeable – 20 percent or more – to reduce soda purchases (according to Dr. Hammond, we don’t know yet how beverage substitution, e.g. giving up Coke but drinking more Gatorade, factors into measuring the impact). New supermarkets have opened in so-called food deserts, and farmers’ markets have added numerous lower income-targeted incentives such as the “Double-up Bucks” program. And the list goes on: labeling to identify calories in each menu item, promoting breastfeeding, and using public facilities, trails, rails, and streets to make us sweat profusely.

All of these interventions can make a dent in human behavior, but applied as stand-alone actions, their impacts are often marginal. That is why they must be applied together in an interactive and coordinated fashion, and that is why the gold standard for a comprehensive obesity prevention strategy, at least so far, is Shape Up Somerville (Massachusetts) https://www.somervillema.gov/departments/health-and-human-services/shape-up-somerville. This community level, highly coordinated initiative was begun in 2005 and continues to this day. From the city’s Mayor, to a wide swath of community residents, to all the usual institution and organization stakeholders, Shape Up Somerville has brought the community together to mount what can only be called a full court press against obesity. Among other positive measures, results so far indicate that body mass index (BMI) levels for children have declined. About Shape Up Somerville, Dr. Hammond has said, “There is a growing consensus that what we need to do to prevent obesity is to coordinate activity across different sectors and different levels of scale, or to take what is a systems approach.”

When it comes to slowing the runaway train of obesity and ensuring the health of this and future generations of children, collaboration is the noise that “surround sound” makes.

March 4, 2018

Springing Into 2018!

I’m happy to report that I am out and about this year with several trainings, speaking engagements, and book promotion events. But before I share a quick a run down of where, what, and when, let me first say that there are still copies of my new book Stand Together or Starve Alone available for purchase at the 20% discount level. Go to the site: https://www.abc-clio.com/ABC-CLIOCorporate/SearchResults.aspx?type=a. Then go to checkout and enter the discount code Q11820. Remember, this discount ends on March 31. I’ve also beefed up my Linked-in, Facebook, and Twitter presence, so check me out at linkedin.com/in/mark-winne-5829295, www.facebook.com/markwinne, markwinne@MarkWinneFood.

Now for the fun stuff:

Laredo, Texas – January 23 & 24: I had the pleasure of spending two great days with over 150 fine food people and the Department of Health in the border town of Laredo. Two food policy council workshops and a community talk brought stakeholders together to plan for a more sustainable and equitable food system.

Santa Fe, New Mexico – February 13: I appeared on the KTRC’s Richard Eads show to promote Stand Together. Listen to the podcast here: https://santafe.com/ktrc/podcasts/mark-winne-author-of-stand-together-or-starve-alone-and-member-of-santa-fe.

Bridgeport, Connecticut – March 1: I got some radio airtime with some old Connecticut food friends on WPKN Bridgeport, Connecticut.

March 8 – 10 AM EST – Public Radio Network. I will interview live with Bhavani Jaroff on the Progressive Radio Network (PRN). For more information on how to tune in and find podcasts, go to: http://www.ieatgreen.com/events/radio-show/

Baltimore, Maryland – March 8 at 12:00 noon. I will give a book talk from Stand Together or Starve Alone that will include a panel of students and staff from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. The location is the Bloomberg School of Public Health, Room W5008, 615 N. Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD. A book signing will follow, and rumor has it that the incredibly awesome “Stand Together or Starve Alone” bumper stickers will be available for free!

Albuquerque, New Mexico – March 27 – National Good Food Network Conference. I will be conducting a half-day short course at the NGFN conference. The course will examine the connection between food policy councils and food hubs. For more information: https://www.winrock.org/ms/national-good-food-network-conference/.

Hempstead, New York – April 19 from 8:30 to 12:30. I will give a keynote address to a food conference sponsored by the Long Island Food Coalition, the North Shore Land Alliance, and Hofstra University. For more information contact Annetta Centrella-Vitale at Annetta.Centrellavitale@Hofstra.edu.

Cincinnati, Ohio – April 27 – National Farm to Cafeteria Conference. Along with my Center for a Livable Future colleague, Raychel Santos, I will be doing a half-day short course on the relationship between food policy councils and farm to school/cafeteria. For more information go to www.farmtoschool.org.

Orlando, Florida – June 22 and 23 – Florida Food Policy Council Annual Meeting. I will be giving a keynote address. For more information contact Rachel Shapiro at rachel@integroushealthsolutions.com.

Stay tuned for visits to Georgia in early May, Youngstown, Ohio in late April, and Bethlehem, Pennsylvania this Spring.

January 25, 2018

Join Mark Winne and Friends for a Webinar that asks, “Can the Food Movement Stand Together?”

You are invited to a Zoom webinar.

When: Feb 2, 2018 (Ground Hog Day) 1:00 PM Eastern Time (US and Canada)

Topic: Can the Food Movement Stand Together?. Join Mark Winne and friends for some answers.

Register in advance for this webinar:

https://zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_ar-9UowQR1-aGGSpkGpwyw

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the webinar.

———-

Webinar Speaker:

Mark Winne (Author @markwinne.com)

What better way to celebrate Ground Hog Day than a conversation about how the food movement is stuck in a hole. In his latest book, Stand Together or Starve Alone, 45-year veteran Mark Winne posits that the food movement must learn to collaborate or it will wither on the vine. Join him and some of his incredibly insightful friends for a conversation about building a better movement.

The Friends:

Anne Palmer, Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, Webinar Moderator

Andy Fisher, Author, Big Hunger

Kwabena Nkromo, Atlanta Food Activist

Hank Herrera, C-Prep and California Food Activist

Joann Lo, Food Chain Workers

Michael Rozyne, Red Tomato Founder and Evangelist

Cindy Gentry, Maricopa County (AZ) Health Department and AZ Food Activist

Martin Bailkey, formerly of Growing Power, Wisconsin Food Activist

Mark Winne's Blog

- Mark Winne's profile

- 5 followers