Mark Winne's Blog, page 6

January 24, 2021

The No-Nonsense Guide to Joy: Wayne Roberts – 1944 to 2021

Wayne Roberts, the Canadian food activist, writer, and unequalled lover of life passed away early the morning of January 20th. Seems only right, I guess, that one luminous northern star would fade on the same day that America’s four years of darkness would give way to an effulgence of hope and light. I’m sure Wayne didn’t plan it that way, but there’s something in the timing that can’t be denied; that maybe his ineffable being, a soul that kept all who knew him merry and optimistic, flickered just long enough to help us Americans find our way to higher ground.

I quickly filled an old, large envelope fished out of the recycling bin with memories of Wayne (I heard him chastise me for even thinking about scribbling notes on a fresh legal pad). The remembrance that immediately rose to the top concerned our trip together to South Korea. As part of an international delegation to advise cities on sustainable food practices and policies, we found ourselves early one morning, jet-lagged, wondering the streets of Suncheon, a city at the very southern end of the Korean peninsula. Lost in conversation and succumbing to chronic giggling syndrome (CGS) – a condition in which you often found yourself when in Wayne’s company – we soon discovered that we were hopelessly lost. Without a non-Asian nor English-speaking person in sight, Wayne stopped the first Korean who crossed our path to ask directions to our hotel. Not understanding a word of English, the man stared at us blankly causing Wayne to ask him the same question in Spanish, to which the poor fellow appeared equally dumbfounded. When I asked Wayne why he used Spanish, he said, “It’s the only foreign language I know.”

Countless friends and colleagues will no doubt sit around the campfire and regale each other with Wayne stories long into the night. Their mirth will rise like the fire’s dancing embers setting off rolling claps of heavenly applause among the night time spirits. But as much as his joy has filled our lives to bursting, I count myself equally fortunate to have benefitted from his instruction, fueled as it was by his sense of urgency that we get right with our food system. As the head of the Toronto Food Policy Council, certainly one of the most successful bodies of its kind in the world, Wayne would bestow upon me – as he did with all he worked – tips, insights, and lessons-learned. As an early practitioner in the evolving art of food policy councils, I would soak up every drop of Wayne’s wisdom in hopes of making my own council in Hartford, Connecticut shine with as much luster and abundance as Toronto’s.

As an early and surprisingly older adapter of social media, Wayne would continually harangue me to use it as avidly as he did. While not sharing his enthusiasm for its power and reach, I would nevertheless try to heed his advice – cursing him in the process – and push my reluctant, Luddite self further. Sharing hotel rooms at conferences and Community Food Security Coalition meetings (Wayne was a dedicated CFSC board member), he was always generous with his advice on life, love, and difficult personalities. Those rooms, now scrubbed clean, I hope, of every remnant of politically incorrect male behavior, reverberated with an intoxicating mix of jubilation and profound lessons. If the holiness of someone’s love is best revealed by the depth of their listening, then Wayne may very well have walked on water.

As much as he was a world-class talker, Wayne was equally committed to putting his words on paper. We both held a passion for writing, not only as a way to share our learnings with the growing food movement, but to give full throat to our creative yearnings. My then-wife, Pam Roy, and I gave Wayne a place for a writer’s retreat during the winter of 2007 in Santa Fe. He used the time to pen The No-Nonsense Guide to World Food (New Internationalist Publications), a pithy and pocket-size extrapolation of Wayne’s world-wanderings, practice, and research. It gleans what truth he could from a global food system teetering dangerously close to collapse, and prods us to take action. Though he may have possessed the persona of a jokester, Wayne’s talks and writings made you pay attention, like your life – and the life of the planet – depended on it. And they gave you hope, as in these lines from No-Nonsense: “Food is most challenging to people with a Modernist upbringing because warming to food is about warming to this humility, this awareness of the oneness and connectedness of, and responsibility to, all beings. This is what food system redesign is nurtured by and grows on. It’s hopeful, it’s positive, it’s fun….”

Wayne’s generosity knew no borders. It flowed unchecked across international boundaries with an ease unnoticed by security, but always appreciated in Detroit, London, or Seoul. His heartfelt, always present presence will be sorely missed. Like Hamlet speaking of his childhood mentor, Yoric, “…a fellow of infinite jest, of utmost fancy,” we will also ask, “Where are your gibes…your gambols…your flashes of merriment that were wont to set the table on a roar?” I will answer by saying they are still there as a reminder to us all that a passion for justice and sustainability can walk hand-in-hand with love and humor. That was Wayne’s way; let’s celebrate his life by making it ours as well.

January 3, 2021

The Zen of Reflecting Forward

Staring back in the mirror at my aging visage while thinking ahead to retirement’s uncertain temptations, I’m frequently tormented by the question of today’s purpose. Fifty years of food movement engagement have left in my wake many exciting achievements, some projects stalled in traffic, and even a multi-car pile-up or two. But as much as I try to live in the present with its suffocating over-stimulation, I’m dragged back to the past by Robert Frost’s lines that “[Life] lives less in the present/Than in the future always/And less in both together/Than the past.” Some say the past is a guide to the future. I’m inclined to say that it is the future.

As my senior moments these days attest, my short-term memory may be atrocious (“What was that person’s name I spoke to on Zoom yesterday?”), but my long-term appraisal of the past is performed with surprising clarity. A case in point is, coincidentally, another “senior moment” because it harkens back to my senior year as a member of the high school track team. My three years as a 400-meter runner had been less than illustrious. Since I placed in the top three in only a handful of races, Coach Palmisano would frequently stick me on the four-man, mile-relay team whose members were fast but not fast enough for the 400-meter – the so-called “Big Time.”

With an extra inch or two in my stride and a strong kick at the finish, I assumed my last year of high school would make me the premier 400-meter man. As fate would have it, along comes a sophomore who must have been cloned from a jaguar. His stride was so natural and speed so enduring that he’d break the tape without breaking a sweat. For most meets, this left me and three other sophomores on the mile-relay team. While not exactly a disgrace, I did notice that more than one woman I asked out told me, “Sorry, I’m busy that night.”

By the time of the season-ending league tournament in June, I’d pretty much had it. Accepted to college and with graduation only a week away, I had lapsed into coasting mode. Skipping the tournament seemed like an easy decision that Saturday morning when I turned off my alarm and caught several more winks instead of boarding the bus with my teammates. That is until the call I got late that afternoon from Coach Palmisano. “Where were you, Mark?” My reply was thin, evasive, and ultimately defeatist, echoing my frustration at only being second best. “Well, you let down three young men who wanted to run today. Because you weren’t there, they couldn’t compete.”

Now, Coach was a second-generation North Jersey Italian. All 5 feet, 4 inches, of him would occupy the track’s finish line zone where he held court with a stop watch dangling from his neck, a clipboard clutched in one beefy paw, and clouds of cigar smoke enveloping his balding head. His words of encouragement, uttered no more than 12 inches from your face, would end with small bits of saliva-soaked cigar wrappings stuck to your cheeks. What he lacked in the nuance of motivational sports psychology, he more than made up for with blunt emotional force.

Deep shame has a way of embedding its daggers forever in your consciousness. Palmisano’s call lasted less than three-minutes but it has played a continuous loop in my head, off and on, for decades. First it was the guilt associated with simply not showing up, but later—many years later—it dawned on me that guilt and six dollars will only get you a double latte. The failure that wrapped itself around me like a stiff, unwashed blanket was not knowing my role in life at a moment when it mattered most; it was falling prey to a bruised ego that told me that if I can’t be number one, I wouldn’t play at all; it was a failure to recognize that all of us, at some point in our lives, whether at 18 or 70, will be eclipsed by others.

None of these shortcomings should mean that we don’t have a role to play, or that we can’t use our reservoir of accumulated wisdom to help others play the game as well as they can. Like Coach Palmisano who most likely forgot about me within a few weeks, I have forgotten, or even never knew the people I may have influenced along the way. But now and again, a ripple I set in motion years ago ricochets off some distant shore to return and gently lap the hull of my boat. Such wavelets have come in the form of 20-or 30-year-old food movement activists who credit one of my books for the career choice they made. In a similar vein, I’m often shaken from my blasé mind set when participants in my trainings and consultations share helpful revelations that resulted from my advice. Most rewarding of all have been the projects and initiatives I had a hand setting in motion, some as far back as 50 years ago, that remain in place today. They are usually bigger, stronger, and often quite different than what I originally imagined, yet they continue in their own ways to make important differences in the lives of others. As far as someone might stroll down memory lane, they will never glean enough from their own history to measure the impact they have had on others.

Your past may portend your future, but knowing your appointed role in the moment allows you to create new feasts rather than merely eat your leftovers. Like a rolling dharma train, I might, alternately, offer to take the lead, be a supporter, be a donor, or be “an attendant lord…to swell a progress, start a scene or two.” Sometimes I might write the book, but more frequently I now write the forward or an endorsement for another author, or help a new author find a way to share their voice. And to the dismay of those who tried to instruct me in my early years, I will become the teacher, even the coach, and sometimes, with less humility, the water boy. I will strive to speak less, and smile more because my encouragement is more important than my ideas.

Though my part is smaller, the briefer moments on stage still matter, partly because there are now so many more players, a bigger stage, and, in fact, more stages on which to perform. That should be nothing to complain about since it recognizes the growth and diversity of the food movement. We should at this point recognize—perhaps even celebrate—three, maybe four generations of food activists. While at times this much activity might feel like a chaotic, three-ring circus, it is certainly not a dilution of the movement, but rather an enrichment and enhancement of an ever-unfolding history; a history that continues to fuel the future.

To my former three sophomore mile-relay team members, wherever you are, I apologize for my indolence and self-pity. I hope the harm I caused you was short-lived. To Coach Palmisano, resting comfortably, I trust, in some grassy New Jersey cemetery, a soft haze of cigar smoke rising from your grave, let me say thank you for kicking my ass. Though I may still be sore, the point has been taken many times over.

December 1, 2020

Will Speak for Book Purchases

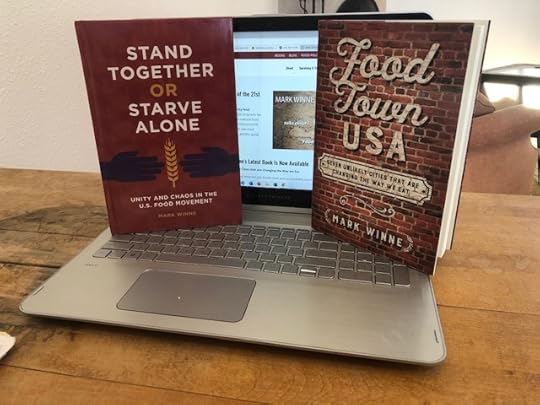

COVID-19 has forced more college and university courses to be conducted online. At the same time, it has curtailed travel by itinerant speakers and lecturers like myself. Since I deeply miss the opportunity to interact with students – and one or two have even acknowledged that they miss hearing from me – I wish to make myself available for online presentations during the remainder of the COVID-19 emergency. In lieu of paying me a fee or honorarium, I am requesting that schools make a volume purchase of one or more of my books commensurate, more or less, with the number of participants.

COVID-19 has forced more college and university courses to be conducted online. At the same time, it has curtailed travel by itinerant speakers and lecturers like myself. Since I deeply miss the opportunity to interact with students – and one or two have even acknowledged that they miss hearing from me – I wish to make myself available for online presentations during the remainder of the COVID-19 emergency. In lieu of paying me a fee or honorarium, I am requesting that schools make a volume purchase of one or more of my books commensurate, more or less, with the number of participants.

Sharing my learnings from 50 years of community food system work, both in person and in writing, has been a passion I’ve pursued over the past decade. While the virus has turned the world upside down, the lockdowns, shelter-in-place orders, and quarantines have also wiped out my travel schedule. Admittedly, this has drastically shrunk my carbon footprint and forced me to learn how to use Zoom, but it has also thwarted my yearning to connect more immediately with the food movement’s veterans and newbies.

Virtual speaking events over the past summer and fall – to college classes, conferences, and book clubs – have taught me that online communication can be the next best thing to being there. To that end, I’m happy to work with faculty and students to design a presentation that gives you the content and format that works best for your particular course, seminar, or other sessions and meetings. Generally, I want to stay within the framework of my most recent books, Food Town, USA and Stand Together or Starve Alone, which should allow ample room to explore current food system topics such as sustainability, racial equity and inclusivity, food policy, the response to COVID-19, and how food and community economic development are finding common paths. More information about my background, books, and other writing can be found at www.markwinne.com

To quote our President-elect, “Here’s the deal:” Please contact me by phone (860-558-8226) or email (win5m@aol.com) to discuss your proposed event (e.g. course, seminar, gathering). I encourage you to share as much detail about it as you like. Together, we can determine if I can meet your content and scheduling needs. I will give you book purchase information to make a volume purchase for Food Town, USA (Island Press) and/or Stand Together (Praeger/ABC-CLIO). E-books as well as print copies are available, as is volume discount pricing for print editions. The purchase must be completed before the scheduled presentation. I’m flexible and sometimes versatile, so don’t be afraid to suggest alternative ways of making a presentation work.

I look forward to hearing from you as well as “getting back on the road,” virtually!

November 16, 2020

The Wall Within

I’m sitting at a bar in Santa Fe having a drink with a friend. The time is last February and we had just come from a fundraiser for Congresswoman Xochtl Torres Small (“Xoch”), New Mexico’s first-term Democrat for the state’s Second Congressional District. It was the kind of house party that rich Santa Fe liberals love to sponsor, and the kind of event that candidates from resource-poor, red-leaning districts love to attend (NM CD-2 is mostly rural, one of the largest districts in the country, and about 100 miles south of Santa Fe). I’m chatting with the former head of the state’s Democratic party who tells me that the vast majority of donations to New Mexico Democratic candidates for national office, regardless of what district they represent, come from Santa Fe. As I cast an eye at the surrounding real estate, I reckon that most of that money doesn’t have far to travel.

Meanwhile, back at the bar, my friend and I are basking in the glow of having basked in the glow of so much wealth. Whether it was the private home’s museum-worthy art collection, the valet parking, or almost falling into the indoor pool as I retrieved my coat, I do confess an occasional fondness for a lifestyle I have no hope of ever attaining. We were stirred, however, from our reverie by a large cowboy perched two stools down. Even sitting ramrod-straight I had to look up at him, to say nothing of his hat that added another story to his height. Noticing the “Xoch for Congress” stickers still plastered to our jackets, he politely inquired if we were supporters. Smiling sweetly and with less-than-normal assertiveness, we acknowledged we were, even though we didn’t live in her district.

Worried that I might end up on the bad end of a barroom brawl, I was pleasantly surprised by the ensuing conversation. He told us that his cattle ranch was along the New Mexico/Mexico border, which made him a constituent of Torres Small. He was in our state capitol to lobby (the legislature was in session) for reduced environmental regulations. Not sensing that he was trying to be overly solicitous of our feelings, he acknowledged that he liked Torres Small and believed that she was making a genuine effort to serve everyone, even though he made it clear he wasn’t going to vote for her.

But when we asked him what he thought of environmental regulations and the border wall (the untouchable third rail in many political conversations), his posture became more rigid and his eyes averted ours. “I don’t want anyone telling me how to raise my cattle or care for my land! They are my livelihood and I’m not going to do anything to harm them. I know best, not the environmentalists!” And the Wall? “Well, I’ve found copies of the Qur’an on my ranch.” Aside from pronouncing Islam’s holy book as if it rhymed with “doe ran,” I suspected that this was more than a local littering problem for him. Trying to conceal my astonishment, I asked, “Do you mean that Muslim terrorists are infiltrating the U.S. from Mexico?” “Yup,” he responded, “that’s why we need The Wall.” After a faltering attempt to regain our cordial conversation, we eventually made our excuses and asked for the tab. In a gracious, gentlemanly manner, he tipped his cowboy hat saying, “Good night, sir; have a good evening ma’am.”

By midnight on November 3rd, the state’s media had called the NM CD-2 race for Xoch’s opponent, Yvette Harrell, whom she had beat in the 2018 election by less than 4,000 votes. This time around Xoch lost by 20,000 votes. I had made a decision last spring to direct the lion’s share of my political contributions to three, first-term Democratic congresswomen who had flipped their previously Republican districts in 2018. I was shocked to learn that in addition to Xoch, Congresswomen Kendra Horn of Oklahoma’s Fifth Congressional District and Abby Finkenauer of Iowa’s First Congressional District also lost by significant margins. As I told my son the following day, “I got bad news and worse news. The bad news is that everybody I gave money to (except Biden) lost.” “What’s the worse news?” he asked. “That money was your inheritance.”

The question, of course, is what had changed in two short years? Aside from the constant Trumpian drumbeat of lies, hate, and fear, had these previously Republican districts that voted blue in 2018 just been an anomaly? Had those voters suddenly seen the error of their ways and used the 2020 election to repent? Three highly competent and moderate Democratic women were serving their respective districts with diligence and a daintiness of ear to listen carefully to everyone – including my cowboy friend with the Islamic litter problem. Torres Small and Oklahoma’s Horn had major oil and gas interests in their districts that could not be dismissed. Consequently, neither congresswoman could embrace a wholesale fracking ban nor throw their hats into the Green New Deal ring without suffering political damage. In Torres Small’s case, she had worked so well with her district’s oil and gas industry over the past two years that she had earned a “neutral” rating from them, which for a New Mexico Democrat is like having Red Sox fans publicly admit that Yankee fans have no clinically proven psychological defects.

In Congresswoman Horn’s case, she had championed a proposal to double the Earned Income Tax Credit for working families, and otherwise maintained a moderate stance as a fiscally conservative “Blue Dog” Democrat. Her victorious Republican opponent, Stephanie Bice, brazenly touted her own support for big oil and gas interests as well as her A-plus rating with the NRA and the endorsement from the Oklahoma Right to Life chapter.

In an attempt to appeal to her district’s hunter/gatherer crowd, Torres Small tried to burnish her gun cred by running so many ads demonstrating her shooting prowess that, for a moment, I thought she was doing military recruiting spots. But even that was to no avail as her opponent Harrell used her millions in dark money to hammer home the spurious contention that Torres Small had earned a “D minus” rating from the NRA.

According to one Iowa constituent and supporter of Congresswoman Finkenauer, “Nothing Abbey did or did not do [lost her the race]. It was mostly dark money [that paid for] overwhelming ads against her. Iowans seem to not get what is happening to them, so they keep falling for deception.” Unfortunately, as much as these three Democratic gun-totin’, gas-lovin’ gals professed their willingness to work with everyone, they just couldn’t get their heads above the negative tide.

Of course, the Republicans did their almighty best to associate Democrats in these toss-up districts with “socialist” national Democrats. Ads ran non-stop that made it appear as if these smart, independent-thinking women had been lured into a coven headed by the Wiccan high-priestess Nancy Pelosi and her shifty acolyte, AOC. As the Republican ads would have you believe, a vote for these moderate Dems would lead to the downfall of respectable white women who would abandon their maternal and spousal duties in favor of wanton salsa dancing on Main Street.

And it wasn’t for lack of money that these Democrats lost. In addition to all that liberal loot flowing south from Santa Fe, millions came in from out of state for both sides. In the end, Torres Small took in $6.65 million, Harrell garnered $2.46 million, and together they benefited from a combined $21 million in outside PAC money. The cynics among us might be excused for saying that running for office these days is another form of the green new deal.

As I scratched my head at these bewildering results, I asked myself what role COVID-19 played for voters as they entered the voting booth, or, if they were voting Democrat, dropping their ballot into a mailbox. Trump certainly did his level best to divide the nation into two camps: the weenies who wore masks and the real men who show you their angry face beneath a red hat. As time went on and the toll of infected Republicans mounted, that latter camp reminded me of the “Marlboro Man” spoof that had the debilitated, horseback-riding cowboy with plastic tubes up his nostrils and an oxygen pump strapped to his wide leather belt. Torres Small had told a small Zoom gathering of us white-haired, Santa Fe donors that people in many parts of her very large rural district won’t even talk to her when she’s wearing a mask. Trump-inspired or not, the frustration with the COVID-19 lifestyle and the resentment it conjures up toward public health measures was projected sufficiently onto Democratic candidates. After all, many of these anti-mask folks are direct descendants of the anti-motorcycle helmet and anti-car seatbelt crowds. Either way, to mask or not to mask may have been the question that gave the Republicans the edge they needed in rural districts.

If Democrats retain any hope of gaining and holding seats in rural America, they will need to do more than teach their candidates to shoot straight. While my proposal to organize “Muslim Cowboys for Democrats” didn’t get much traction, I’m keeping faith that the party can carve out some pragmatic space that embraces regional differences. One-size-Democrats don’t fit all in an off-the-rack political world. What works in Queens, Detroit, or even Santa Fe, won’t work in Roswell, Oklahoma City, or Dubuque. We need commonsense, smart people with roots in their communities (like these three women) who can find hopeful common ground with those who have, temporarily I believe, fallen under the spell of the fear factor. And we need national party leaders who can celebrate and empower a diverse and robust marketplace of ideas and needs, and accordingly, candidates who can win in those marketplaces. Yes, we strive for party unity, but like a big family with many kids, we’ve got to make room for those, who for good reasons, don’t fit the dominant paradigm.

Then there is the money – oh my God, there is the money! Spending $30 million on a single congressional race may be a new high in political campaign terms, but is certainly a new low for humanity. During one, ten-minute TV segment that aired on a New Mexico station, I saw seven vicious campaign ads – four against Torres Small and three against Harrell – that dumbed down the voters, made a mockery of democracy, and ultimately, if they had the guts to admit it, demeaned those who are responsible for them. When I think of what $30 million dollars could have done for NM CD-2, one of the most impoverished and food insecure districts in the country, I get sick, especially when I realize that some of that campaign cash came from me.

While I consider it a frightful prospect, most of us have become slavishly dependent on TV and social media for candidate information. The ads on both sides are filled with distortions, misinformation, half-truths, and outright lies that in other times and other places would subject their purveyors to legitimate charges of libel and slander. If my young children had said such things about their classmates in days of yore, I might have washed their mouths out with soap. Surely, a civilization that makes its most important choices based on lies will rot from within.

Reform? Sure, but what? Shedding light on the sources of “dark money” isn’t enough. It’s not likely to stop the flow of the buckets of bucks that the rich and famous want to trade for influence. There needs to be absolute limits on the amount of campaign donations and expenditures. How much? I don’t know, but it should be more than the cost of a campaign bus and less than the cost of a new health clinic. Every recognized candidate should be entitled to a fixed number of media ads paid for by the public sector and media outlets. As to the content of those ads, it should comport with new and elevated standards of truth and facts presented in a form that doesn’t scare your children.

We must end the nuclear campaign cash race that is rapidly headed toward mutually assured destruction, not just of the candidates but of democracy. Additionally, the Democratic Party has to embrace a kind of pluralism that holds onto core principles but gives ample room for regional diversity and expression. To that end, there should be deep soul searching and research into the rural American story. The walls that have been built – both the literal one at the border and the figurative ones domestically – between metro and rural areas, so-called liberals and conservatives are based on fear and manipulations by narcissistic people desperate for power. We need to stride forthright into the belly of that fear, where I suspect we will discover more things to like than to hate. To that end, I going to go visit that cowboy and try once again to find out what we have in common.

October 18, 2020

“I’m Tired of Watching Our Town Die”

The vines from the elementary school’s sizeable pumpkin patch were sprawling aggressively across the basketball court. In spite of the 98-degree heat, the plants were so vigorous, so verdant, that one could imagine them ascending and eventually encircling the nearby five-story feed mill that dominated Atwood’s downtown center. Was this a symbolic challenge from an upstart school garden project—a David and Goliath confrontation, as it were—to the commodity feed and livestock farming that defines western Kansas? Perhaps. But more than likely it’s a murmur rising inexorably to a scream from the school’s young people that the status quo may not be enough to keep them around. Because if you climbed to the top of that mill, spread before you would be too many vacant store fronts, too little pedestrian or car traffic, and too little future.

What you’d also see from that precarious perch is the rest of Rawlins County, of which Atwood is its largest town. Stretching out against an endless horizon in all directions is a vast expanse of wheat and feed crop-covered prairie. No less impressive by its absence, you will not see a single stoplight or much in the way of human habitation. Rawlins County, set firmly against the Nebraska border to the north and one county over from Colorado to the west, makes abundant room for a population of barely 2,500 people (down from 3,400 in 1990), which is hardly a regional anomaly. The entire nine-county northwest Kansas area has a population of only 30,000 inhabiting a territory larger than my former home state of Connecticut, which contains 3.2 million people within its borders.

Against a backdrop of commodity crop dominance and a dwindling population, it’s not uncommon to hear some version of a “goodbye to rural America” tune rising from various quarters. But down on Atwood’s quiet streets, a different, more uplifting song can be heard from a growing chorus of people working to create a more hopeful future for this beleaguered corner of America. One of those voices is JoEllyn Argabright, who, in one bold act of derring-do early in the summer of 2020 bought out a closing garden store and two adjoining buildings. Her intent is to transform them into a multi-purpose garden center and food hub. When I asked her why, her response was simple: “I’m tired of watching our town die.”

When Jo, 35, first picked me up for a tour, she identified herself in advance as “the only 5-foot, 3-inch woman in the parking lot with a big black pick-up truck.” If there’s one thing I’ve learned from living in the West, don’t expect small women to always drive a Prius. In this part of world, the vehicle is still a projection of your personality. In Jo’s case, she’s a self-identified “farm wife, mother of two children (two and four years old), Extension educator for Kansas State University, and now a store owner.”

Growing up in Boulder as the only child (her one sibling died in childhood) of a single father—a recently retired Denver emergency room physician—she first attended Colorado State University on a clay pigeon shooting scholarship. (This last item—a women’s Olympic competition since 2000—took me a while to process since I’ve seen shotguns longer than Jo is tall.) Transferring after her freshman year to Kansas State, Jo would acquire undergraduate and graduate degrees that led her to a variety of nutrition and community development positions within the University’s Extension system. Just as importantly, she met her future husband, Austin, at K-State, after which they would return to his family’s farm in Rawlins County.

“My passion is around local food as a way to feed our community,” Jo said as she showed me around her newly acquired properties. While that passion partially explains her motivation to open a food hub in a community where new business startups are nearly as rare as dodo birds, she appears to be mining a deeper vein of personal desire. “I want to create something my kids will be proud of and that will give them a reason to stay here.” But she also shares a personal drive that has ignited her inner entrepreneur. “As a [Kansas State] Extension educator I’m always helping others with business and farm problems. But I’m preaching to them from the safe space of a university. I need to actually do it myself because, like farming, not enough young people want to become merchants.” According to the people I interviewed for this article, Jo is now one of the youngest business owners in the nine-county region.

To say Jo “walks it like she talks it” is an understatement. By her own admission, the comfortable salary she earns from a major state institution places her in the higher echelon of the county’s income earners. But rather than seek high rates of return in the stock market, she’s invested her savings, uncompensated time, and Extension knowledge back in the community. Though the purchase price of the store, its inventory, the greenhouse, a vacant lot, and two adjoining buildings—all tightly packed onto about a quarter acre of land—was at bargain basement rates, a significant sum was still required. She dug into her own savings, secured an “investment” from her father (“I had to agree to let him volunteer at the store in return for his gift,” she noted with a laugh), and took out a long-term, low-interest loan from Network Kansas, a state-sponsored entrepreneur development fund

All of that just gave her title to the properties and a chance to make a go of it in a risky marketplace. The “Dream,” the thing that gets Jo up in the morning will take more money, massive amounts of community support, and, to use her favorite phrase, “a lot of love.” The Dream includes a food hub that features locally produced food and other horticultural products. Already, an heirloom garlic grower wants to sell through the hub, and local beef and pork operations have expressed interest in selling finished retail products there.

A seed-starting greenhouse (Jo has set a goal for the store to start 75 percent of the plants it sells) will be added onto the existing 20-x-48 foot greenhouse. This phase of plan got a boost recently from a $45,000 SPARK grant from the Kansas Department of Commerce as part of the coronavirus stimulus package (Kansas received $9 million in federal funds for local food system promotion). This will include the addition of a walk-in produce cooler and freezer.

Rounding out the entire food center will be a commercial kitchen incubator that will house the equipment, safety training, and other support services necessary to producing and marketing processed food products. Through her Extension work, Jo already has several clients for whom such a facility could launch their much hoped for food businesses. To ignite a food-chain effect, gardening education programs will encourage and support home scale food production and processing that have surged since the appearance of COVID-19. The store’s 2021 calendar of events already has courses on the docket titled “Growing Herbs,” “Cooking with Herbs,” and “Seeds to Sauce.” A café is another logical and likely addition that Jo sees emerging down the road.

Besides this immediate infusion of “emergency” government cash and self-financing, Jo’s hybrid non-profit and for-profit corporate model will enable her to tap into other government and private foundation sources. But the biggest and perhaps least visible part of Jo’s financing plan will be “goodwill”—that squishy financial concept that businesses often use to beef up their anemic balance sheets. Customers are already buying “gift cards” for spring purchases to augment the store’s cash flow, and as many as 35 product vendors are extending credit against the coming year’s inventory.

Chatting with Jo in front of her store late one morning was a lesson in the underlying value of small-town life. A steady trickle of walkers, well-wishers, and honking pick-up truck drivers waved and offered Jo encouragement. In response to a recent request, the local public works director stopped by to trim a beautiful shade tree gracing the store’s curbside—a municipal action that normally takes months in places I’ve lived. Volunteers are already showing up to clean her buildings; high school job-readiness programs will provide apprentice workers; and one citizen has offered to front Jo the funds to support this much-needed business (Jo said, “She told me, ‘you can pay me back whenever’”). Call it an old-fashion barn raising event writ large, a form of community-supported capitalism supplanting the failures of conventional capitalism, or a welling up of social capital that small towns draw on to keep their faltering hearts beating; the goodwill I saw in Atwood is something you can take to the bank.

Jo’s store is the train leaving the station that everyone is clamoring to be onboard. As one local resident told me, “we’re all longin’ for belongin’” meaning that in an area where people often feel socially isolated because they may live miles from the nearest person, the need for “connectedness” becomes palpable. “There’s a strange juxtaposition between feeling isolated in a rural community at the same time you feel connected,” reflected Jo over lunch at the Mojo Café where we sat with Travis Rickford and Courtney Schamberger. Travis, who is the Executive Director of the Live Well Northwest Kansas, an agency that advocates for the expansion of mental health services, explained that “connection comes when there’s a crisis like the way people do when someone dies.” But he notes that social isolation is why rural suicide rates are higher than average, and that “togetherness” is not always the answer. “With COVID forcing households to stay closer than normal, we’ve seen a 200 percent increase in the number of calls to our domestic violence hotline.” Travis points out that right now the region has a “perfect storm of things that prevent families from thriving and are contributing to anxiety and depression” including the stressed farm economy (e.g. fluctuating crop prices), COVID, substance abuse (opioid use is high), and the continuing lack of an adequate health care infrastructure.

These are the burdens that rural America has been carrying for far too long, and ring like sirens in the ears of those under 40 years of age. When Jo’s youngest child was only one, he stopped breathing in his crib. She revived him but his care required immediate medical helicopter transport to Denver. When the team of specialized pediatric health providers prepared instructions for Jo to pass onto her pediatrician, she nearly choked, “What good is that? I’d have to drive three hours to get to a pediatrician!”

Events like this don’t deter a generation of 20 and 30 somethings. If anything, they seem to strengthen their resolve to become the next generation of leaders their communities need. Courtney, who’s in her mid-twenties and a vocational agriculture teacher at the local high school, says, “My age group should be stepping up to provide leadership because we are the future of this town. I’ve only been here four years and I’m already on five boards.” She’s a little frustrated that more of her peers aren’t doing the same, but has faith that her community is going to turn around. “There are more people shopping locally, and mutual support for our businesses, artists, and craftspeople is growing.”

Evidence of a trending upward in young people is supported by an enrollment uptick in Rawlins County middle and high school students this year. Overall, a more robust participation by a younger demographic is confirmed by Misty Jimerson, the Coordinator of the nine-county Western Prairie Food Farm and Community Alliance which monitors and supports new food system activity. “We are seeing young folks moving back and starting businesses, including restaurants, that use more locally grown food. This is developing new markets in our region for food that people actually eat.”

Another trend gaining traction—one that could not have been predicted—is an influx of coronavirus “refugees” from places like metro-Denver. Like those who left New York City after 9/11, the fear that densely populated urban/suburban areas are more life-threatening is driving people into the arms of low-density, rural areas that may be as much as three to four-hour drives from “hotspots.” According to local real estate agents, the last 12 homes in Hitchcock County, Nebraska (pop. 2,900)—bordering Rawlins County to the north—went to Colorado buyers, as did most of the recent home sales in Herndon, Kansas (pop. 129) located in Rawlins County. Apparently, these agents have long waiting lists of out-of-staters searching for rural properties.

Shortly after Jo took possession of her new enterprise, she was pawing through the store’s second floor inventory that was not accessible to shoppers. She was startled to find full bottles of DDT and arsenic, substances long banned from agricultural use. The safe removal and disposal of these dangerous vestiges of the region’s agricultural past were now Jo’s responsibility. In other words, she had inherited the sins of her forbearers, but rather than rail against the injustice, she arranged with the county’s hazardous waste disposal facility to take charge of these items. It was a symbolic passing of the torch from an unsustainable form of food production to one that is placing people, community, and the environment at the center of a very local plate. Her discovery reminds us that we don’t always like what we find in our parent’s attic, but we learn to live with what we can, dispose of that which is intolerable, and set a course for a better future.

In Atwood, Kansas, and across rural America, that course does not include a wholesale rejection of the old, but a reinvention and a Millennial-inspired repurposing of what is already there. “I’m going to run a different kind of business,” Jo firmly asserted, “one that is hyper-local with its merchandise, community-oriented in its approach, and based on the proposition that we will thrive, not just survive.” As we toured the still disheveled second floor, now purged of its toxic substances and beginning to be reimagined as a healthy, creative space, Jo said, “We just gotta give it some love!” As she knew, that also meant more young people, local food driving a local economy, public and private financing, and a community that believes in itself.

September 7, 2020

It’s Not Easy Being a Commercial Egg Farmer

First off, I’m not sure if Randy Cruz’s Cruz Ranch in Sapello, New Mexico is the region’s biggest egg producer. Clawing my way through USDA’s 2017 Agriculture Statistics seems to suggest that out of the state’s 2,848 farms that reported raising poultry, the Cruz Ranch was easily in the top ten. What I do know is that turning 70 hilly acres in Northern New Mexico into a commercial egg-laying operation was an uphill climb requiring love, intelligence, and money. What I also learned is that staying in business takes blood, guts, and more money.

Take the night in early October last year when there were about 2,700 laying hens and an assortment of ducks, turkeys, geese, and peacocks tucked safely into their coops when Randy went to bed. When he woke the next morning, the number of birds had plummeted to 1500. The scene that greeted him was one of carnage as nearly 1200 birds lay dead and dismembered about the coops and yard. He didn’t need to gather any forensic evidence to determine that this was not the work of coyotes. The nonsensical killing had been committed by his neighbor’s four German shepherds that had tunneled under the yard’s fence.

The Cruz Ranch story started five years ago when Randy and his then-partner and now husband, Dan, decided to return from their home in Palm Springs, California to start a farm in Northern New Mexico. Randy had been raised on a 6,000-acre ranch in nearby Gascan as part of his family’s third generation in the same house. There, he developed a love/hate relationship with the region that is known for its stunning beauty and agrarian lifestyle, but offers little opportunity. “My mother divorced my father who was the town drunk,” Randy tells me. “We then moved to Oregon which was the best thing that ever happened to us. If I had stayed, I would’ve become a drunk or a loser.”

Randy, 60, uses disarming candor to explain why he chose to take up farming, which was not a part of his upbringing. “I needed something to do that used up my energy and was fun,” he said. Since he’s constantly in motion, it’s obvious why he chose something as physical as farming. But making the leap from a comfortable California lifestyle to farming life in New Mexico’s mountains, even when you have roots there, is a big one. Initially unfamiliar with commercial poultry methods, Randy learned everything possible about eggs, chickens, and birds that quack and gobble from books he’d read late into the night. Starting out with 100 chickens, he quickly lost 45 to neighbors’ dogs and coyotes. He ordered 300 more chickens, reinforced his fences, and added a couple of border collies to perform security and herding duties.

With hundreds of chickens each laying an egg a day, ducks a little less, and turkeys one every two days, Randy soon had the supply he needed to meet the demand generated by a growing list of loyal customers. Restaurants in and around Santa Fe, Cid’s Food Market in Taos, the Dixon Food Coop, and three farmers’ markets comprised the largest portion of his customer base. While his eggs weren’t certified USDA organic, most of his chicken feed was and his birds were running free and easy under the New Mexico sun in a generously-sized yard planted in cover crops. Things were hectic, Randy was hustling and happy, especially after a farmers’ market when he brought home a bundle of cash.

There’s another part of Randy’s start up story that also requires mention. He wasn’t a young hippie who lived out of the back of a van trying to make a go of farming with some borrowed parental bucks and a used rototiller. Randy and Dan had been sufficiently successful in business in California to buy the Sapello property, a former religious retreat center, without going into debt. They also drew on their own resources for working capital. “It takes five to seven months of feed, water, heat lamps, and hard, caring work before a chicken lays a single egg,” Randy tells me, noting that $13,000 in feed alone is required to fill his three grain bins. Even when the first eggs finally appear, they are generally too small for commercial sale, so Randy donates them to the Bienvenidos Outreach Food Pantry.

A sufficient supply of start-up capital, however, doesn’t insulate you from the misfortunes of farming. When I learned of Randy’s chicken slaughter, I asked him if he was going to have the dogs put down and seek restitution from their owners. He said no, “I have to live with these neighbors, and full restitution for my losses would break them.” But he soon discovered that his charitable impulses had limits. Three weeks later, the same German shepherds returned, and this time Randy caught them in the act. After they killed 34 turkeys, 6 peacocks, and 125 pullets, Randy shot three of the marauding dogs. His patience exhausted; he filed a lawsuit against their owner.

“It was a real awful thing,” he told me over the phone. “The dogs were looking back at me when I had cornered them in the barn as if to say, ‘it’s not our fault, we’re just dogs; it’s our owner’s fault.’ I hated to do it.” He pain was palpable, and his reluctance to escalate the conflict with his neighbor was evident. But he felt there was no other way if he wanted to stay in business.

Covid-19

In a twist of Old Testament fury, the coronavirus swept into New Mexico upending the state’s food system applecart. While one might expect that this unforeseen event likened Randy to Job – chickens smote by dogs, a plague devouring the land – something different occurred. Suddenly demand for locally grown food went through the roof. “Egg sales are out of control,” he told me in late March. People were suddenly making hour-and-a-half drives to his farm from Santa Fe to buy a case of eggs (135). Randy said, “It’s nice that people are coming to my farm; they’ve never done that before.”

Even though his three regular farmers’ markets keep him busy, Randy’s received requests from the Santa Fe Farmers’ Market to sell there. He’s lost his restaurant sales due to the virus, but he can sell everything he produces now to Cid’s. But this is when one injustice closes a door at the same time another one opens. Randy’s egg supply is well down because he’s still recovering from the great fall poultry massacre. “Cid’s wants to buy 16 to 18 cases a week, but I can only produce enough now to sell them 6.” In other words, the coronavirus has created demand for Randy’s egg that he can’t fulfill until the replacement birds are fully producing.

Randy Cruz is a resilient and commercially viable farmer. But the threats are always lurking, sometimes from as close as next door, and other times from across the globe. Your chances of survival are enhanced if you can draw on a reservoir of working capital to weather farming’s uncertainties. Therein lies a lesson for today’s foodies: either we as a community underwrite the risk that our local farmers face – in other words, we become their insurance policy – or we rely on well-financed forms of corporate agriculture. Summing up the challenges, Randy said, “If I was poor, I would’ve been shattered long ago. You need deep pockets to be independent and operate, even at my modest scale.”

August 2, 2020

Permit Me a Moment of Outrage

Kimora “Kimmie” Lynum, age 9, passed away two weeks ago from the novel coronavirus. She was the youngest person to die in Florida, where negligent public officials and lax public attitudes toward the virus have catapulted the Sunshine State into first place ahead of New York and California for the highest number of confirmed infections as of July 30th – 461,379 (7/30). Florida’s death toll stands at 6,586.

Kimmie was described in the state’s media as “jovial, fun-loving, and free-spirited; sociable, inquisitive, and always happy.” Tragically, she was a victim of a pandemic that is proving increasingly indifferent to age, but whose spread is aided and abetted by thoughtless politicians. It is also worth knowing that Kimmie is Black, and that she and her family live in Putnam County, Florida. By now it is almost universally acknowledged, at least among those who believe the South will not rise again, that people of color get less of the good things like education and health care, and more of the bad things, like hunger and higher mortality rates. In Putnam County, where 17 percent of the population is Black, 27 percent of the diagnosed COVID-19 infections are among Black people. But as we learn more everyday about how place matters, we find that location, zip codes, and even the block where we live determine who gets the good things and who gets the bad things. And if local health and poverty statistics are part of your selection criteria when searching for a place to live, in all likelihood, Putnam County will not be on your list.

I first became aware of the county—located southwest of Jacksonville and west of St. Augustine—when I was researching my recent book Foodtown, USA. As I was interviewing people associated with food and health programs in Florida’s northeast region, several of them suggested that I visit Putnam. They offered two reasons: it had earned the dubious distinction of being selected by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as the Florida county with the worst health outcomes—67th out of 67 counties (2016)—and it also has a $750 million agricultural industry that produces potatoes, cabbage, corn, and broccoli for America’s winter market. Seeing poverty and a community’s degraded health status cozied up next to vast reservoirs of agricultural abundance may be no surprise to food justice advocates, but it still remains one of those food system conundrums that drives most of us mad.

Running counter to such long standing injustices, I found Angela TenBroeck, a farmer with a mission. She is determined—come hell, Florida’s high waters, or COVID-19—to bring healthy, affordable food to everyone in her region. Working over the past several years to adapt innovative agricultural technology to Jacksonville’s urban spaces, she’s located a state-of-the-art aquaculture and hydroponic farm in rural Putnam County. “We’re in the poorest place in Florida,” she tells me, “and you have to drive at least 10 miles from my [Putnam] farm to get to the nearest supermarket.” Angela hopes to remedy part of that problem with her Marine Land Aquaponics farm that is scheduled to come on line in mid-August. With 25,000 square feet of year-around hydroponic produce production and a 7,000-square foot aquaculture system raising striped bass, she already has forward contracts with local school districts to buy her farm’s output.

So, you would think that a county whose primary distinction is coming in dead last in the Robert Wood Johnson “award” for health would be celebrating ventures like Angela’s with a marching band. Unfortunately, Marine Land Aquaponics, which actually did win an award—a $20,000 Guide Well Innovation grant to eliminate food insecurity—was turned down by the County’s commissioners when she asked them to support a $5 million loan request to the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity. The loan would have increased Angela’s operation four-fold, swelled her workforce from its current level of 10 to 50, and grown healthy food at a scale that would make a huge difference in the health status of area residents. According to Angela, one county commissioner told her, “you sound a little green,” green being the new red if you remember the Communist witch hunt days of Senator Joseph McCarthy.

As Angela sees it, “COVID has changed everything. Imported food is not coming in like it used to, which means we’ll be moving to more local food.” But even the most zealous advocates for greater local self-reliance acknowledge healthy food must go hand-in-hand with a prosperous community and an equitable health care system. Laureen Husband, a founding member of the First Coast Food Network and a former Florida Health Department official, points out how Florida’s political leaders have been complicit in downsizing the state’s public health system, which has been a main factor in the rising COVID-19 body count. “So many people in Florida died who did not have to die,” Laureen told me. “If the state had done things right in April [kept beaches and restaurants closed; mandated the wearing of face masks], we wouldn’t be in this mess now.” She noted that Wal-Mart has had the good sense to require all customers to wear masks, and even hands them out at the entrances to their Florida stores. Matters are not helped, however, when virus testing, which Laureen has volunteered to assist with in her Jacksonville community, is not performed adequately. “It often takes two to three weeks before people receive their test results, and even then, all they’ll get is a text message with no information about what to do if they’ve tested positive.”

Putnam County has paid dearly for the State of Florida’s longtime neglect. The lack of investment in its health system infrastructure has placed its 74,000 residents at additional risk, and a lack of diversification in its economy has contributed to its high poverty rate. According to the county’s Palatka Daily News, agriculture represents 38 percent of Putnam’s “gross regional product,” which includes 20,000 acres of potatoes (combined acreage for Putnam and neighboring St. Johns and Flagler counties) produced for Frito-Lay and other potato chip makers. While that may be a badge of honor for the region’s 40 large potato growers, it’s done little to extricate the wider community from the swamp of poverty and substandard health outcomes.

According to the Robert Wood Johnson data (2020), Putnam County’s childhood poverty rate is 33 percent compared to Florida’s 20 percent rate (Florida’s socio-economic and health indicators generally lag behind national averages); 25 percent are in poor or fair health (17 percent for Florida); the adult obesity rate is 39 percent (27 percent for Florida); and there is one primary care physician for every 2,300 residents (Florida is one to 1,380). Where the county equals Florida as a whole, of course, is in the number of uninsured people—about 17 percent. That’s because the state’s political leadership has declined to participate in Medicaid expansion. The national uninsured rate runs around 8 percent.

In one of those ironies that becomes less ironic the more you know about America’s inequalities, Putnam County shares its eastern border with Florida’s wealthiest county—St. Johns, home to the city of St. Augustine. Looking at the RWJ’s figures, it would be hard to find two places so close together, yet so far apart. Even though the population of St. Johns County is 3.5 times larger than Putnam’s, St. Johns coronavirus infections are just 2.75 times more than Putnam’s, and the number of deaths (23) is only half again as great as Putnam’s (15). This is not surprising when you see that St. Johns childhood poverty rate is only 7 percent (33 percent in Putnam) and there is one primary care physician for every 1,050 people (1:2,300 in Putnam). Even when a pandemic is ravaging the same region, even when the hurricanes wash over the same places, even when the same bad state policies and practices govern the same two counties, wealth and whiteness will enable you to weather the storm far better than your poorer and darker neighbors.

It was against this socio-economic and racial backdrop that Kimmie went to the hospital on July 11th complaining of stomach pains and fever. Her examination did not include a test for COVID-19. She was given some Tylenol and a couple of shots and sent home. Six days later she was found unresponsive and efforts to resuscitate her failed. Posthumous tests found she was COVID positive.

According to a family spokesperson, Dejeon Cain, Kimmie was a happy child, but she didn’t even get a chance to live her life. Not only did the medical system fail Kimmie, the social, economic, and political circumstances of her county and state failed her as well. Her chances in life were never as good as a young white girl in next door St. Johns; she never had the same odds as children in places where inspired leaders and social entrepreneurs take thoughtful risks to ensure a prosperous and green future for their citizens; she would always need far greater luck than her privileged peers to live a happy, healthy, and successful life. Let’s direct our outrage at those who must be held accountable, and let’s renew our commitment to building a future where equity and health are a fact of life for all.

June 14, 2020

The Time is Out of Joint – A Father’s Day Message

Now my dears, said old Mrs. Rabbit one morning, you may go into the fields or down the lane, but don’t go into Mr. McGregor’s garden: your Father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor. The Tale of Peter Rabbit by Beatrix Potter

Nature is out of balance, teetering toward an unsavory resolution that may, in fact, be revenge for the abuses that humans have heaped on both the natural world and themselves. “The time is out of joint. O cursed spite that ever I was born to set it right,” lamented Prince Hamlet upon receiving his fearful Father’s Day message from the ghost of the murdered king, his father, to resolve the political imbalance that had befallen Denmark. Like the Prince, we face acts of death and destruction with outpourings of disgust and anger, paralyzed by the uncertainty of our next steps.

Seemingly less dire, but maybe not, another English scribe would write 300 years later of Farmer McGregor who was determined to maintain an ecological balance tilted in favor of his family’s survival. “I’ll grant you the fields and the lanes,” the old Scotsman might have said, “But you damn well better not cross the line into my garden!” Unlike the Dark Dane, McGregor was not plagued by “to be or not to be” questions—it was either him or the effing rabbit!

As a New Age dad, I deliberately left out the fate of Peter Rabbit’s father when reading the tale to my young children. But I was only able to duck my responsibility to inform them of the struggles between life and death for so long. On one occasion I took my then-12-year old daughter to a farmers’ market where she became gleeful upon seeing a sign that read, “Rabbit!” “Oh Daddy,” she said, “let’s go see the bunnies!” I’ll never forget the look on her face when she saw a hunk of raw meat wrapped in cellophane instead of a wiggly pink nose and furry ears.

Lately, I’ve wanted to apologize to my daughter and son, not so much for humanity’s hubristic place atop the food chain, but for the last 20 years of sequential life and death struggles whose resolutions appear increasingly out of reach. Beginning with 9/11 and its subsequent wars of revenge, followed close on by the Great Recession, climate change and its catastrophic weather events, a global pandemic, and chronic police violence, my children have been riders on a storm that makes chaos seem like the new normal. Their grandparents may have suffered through the back-to-back devastations of the Great Depression and World War II, but my children’s generation has so far endured multiple threats of compounding intensity including on-shore terrorism, economic meltdown, rampant inequality, human-induced environmental and social chaos, and an indifferent virus pillaging the land. And my kids are not even half-way through their lives!

Where, if anywhere, does resolution, or at least balance, reside? Can my desire as an informed and empathetic human being to perform useful interventions amidst the chaos find meaningful direction? I looked for some answers in the presumably manageable microcosm of my garden hoping to locate nature’s equilibrium during these out of joint times. With my vanity on full display, I vowed in March to defy the pandemic by planting and harvesting the best garden ever. Bed preparation, though physically demanding, went smoothly, as did indoor seedling production and early outdoor plantings.

Knowing that northern New Mexico’s critters, big and small, eagerly awaited my first tender shoots, I reinforced my backyard fence with the diligence of a soldier preparing for battle – chicken wire was secured to the wooden fence to deter animals from tunneling under; holes and gaps were backfilled with dirt and rocks; mousetraps were set. The welcome mat was put out for helpful predators and scavengers by distributing chicken bones for coyotes and dead mice for ravens. My battle cry was “Reinforce, Repel, Resist, and (if all else fails) Replant!”

But nature looked at my shenanigans and laughed. It was the six-inch long lizards whose puckish personas always make me smile that first tipped me off to my folly. Looking out on my small back terrace I saw three of them squatting side-by-side, staring unflinchingly at the same spot in the backyard. Normally they scurry off when I approach, but this time they held their ground and gaze like hunting dogs on point. I stood quietly behind them sighting over their scaly backs to locate the object of their fascination, which in this case turned out to be a six-feet long bull snake curled in the grass 20-feet away, staring right back at them. Though non-venomous, bull snakes bear a strong resemblance to rattlesnakes and present a frightful appearance to non-snake lovers like me. But as I remind myself when I recoil from seeing one, they are helpful predators that do no harm to my garden, unlike the cute little bunnies that devour my vegetable plants in the time it takes a hungry man to eat his lunch.

What snakes like this signal is an influx of mice, gophers, and the Peter Rabbits of the world, all of which are fully capable of derailing my horticultural ambitions. Recognizing the snake as a harbinger, I launched myself into action: I doubled the number of mice traps that then filled up rapidly, producing a steady stream of rodent carcasses for the neighborhood ravens. I engineered and re-engineered 200-feet of fence line which seemed a formidable barrier until a large rabbit appeared in the middle of my garden! I chased him with a shovel, Farmer McWinne-style, until he found the hole through which he had entered. As soon as I would block that hole, the rabbit(s) would reappear, having tunneled under from a new spot. Whack-a-mole-like, I’d chase him to another newly dug access/egress point which would then be blocked. Etc.

Just when I thought the fence was impregnable, I was dismayed to see the rabbit again, now munching his way through what was once a perfect broccoli plant. Exhausted, but still determined to repel and resist, I gave chase once more, this time desperately hurling my eight-pound shovel, end-over-end, hail-Mary-like, at the fleeing rabbit 30 feet away. God knows how, but I hit and killed him square-on. Feeling more defeated than victorious, I shoveled his remains over the fence to be consumed later by an enthusiastic flock of ravens who like every other representative of Nature’s Kingdom I’ve ever assisted, never sent me a thank you note.

Sadly, the tale doesn’t end there. The following day, just when I was expecting tranquility to settle into my backyard, a baby bunny appeared out of nowhere. Thinking once again that I could encourage him to find a sliver of daylight through which to escape, I gave him a short chase. He turned a corner around one of my raised beds, made a mad dash to the fence, and collided head on with the waiting bull snake which dragged the unlucky critter into its den beneath a rock. It happened so quickly and smoothly that I thought for a moment I had somehow colluded with the snake.

For now, the outcomes look like this: the lizards, no longer feeling stressed over being consumed by the snake are growing in numbers while fattening themselves on thousands of small insects, including “no-see-ums” which had left a dozen angry welts on my legs. The ravens are so full of carrion they can barely fly to their perches in the nearby junipers. The bull snake, as far as I can tell, is resting in his/her den still digesting the rabbit. My vegetable seedlings are thriving and, for the moment, temporarily safe from extinction.

And me? I’m a wreck, an exhausted caricature of Caddyshack’s Bill Murray whose conflict with nature never finds a lasting truce. Having directly and indirectly contributed to the demise of some of my local wildlife, I sleep fitfully, waking to the sound of coyotes whose blood-curdling yelps indicate they have cornered a rabbit. If they had done a better job of maintaining the balance, I thought to myself, I wouldn’t have had to intervene. I could have merely planted my crops and studied recipe books for 10 different ways to prepare Brussel sprouts. Instead, my dreams are filled with angry gangs of 500-pound rabbits determined to even the score.

It was the novel coronavirus that gave me both the time and motivation to not just garden, but to garden with passion. In a so-called normal season. my powers of observation would have been dulled by attentions turned elsewhere—the snakes would be ignored or simply avoided, and the rabbits would consume a more sizeable share of the produce. Monitoring is not a passive activity nor a sometimes thing; it is interactive, dynamic, and not designed for those who desire a more contemplative lifestyle. Tuning into nature’s cues, including its irregularities, breeds understanding, action, an acceptance of chaos, and the need for flexibility.

Like a virus, the destructive forces in my garden can slip in under my radar; once discovered, they move faster than I can initially respond to them, and they eventually “attract” antibodies, in this case predators that slow their advance. Nature likes to do an end-run around our preventions, that’s assuming we even have taken preventive measures. Being incapable of out-foxing it, we try to corral nature once it starts to run rampant, never knowing how much and what kind of fence is required to restrain its excesses.

My natural instinct, my curse if you will, is to try “to set it right.” The apologetic urge directed at my children is a form of guilt that grows out of my (and everyone else’s) failure to prevent or rectify the ever-expanding evils of the 21st century. But there’s some kind of cycle emerging that seems inescapable, somehow pre-ordained that remains to be perfected by those who will take the time to observe, who will study history, and whose response–-action as it were–-will be considered and appropriate. Social chaos and natural chaos, influenced as they are by humankind’s manifest indiscretions, will always make us feel off balance until we examine their root causes and find the patience to work with them rather than against them. A commitment to action is an inevitable consequence of our humanity, heightened of course by our growing frustration that bad stuff keeps happening and that the end gets closer every day. As we know, doing nothing is not an option, but choosing the right thing to do at the right time is an art form worth perfecting.

In the meantime, Mrs. Rabbit will try to protect her children in the same way I try to protect mine, in the same way we must protect the vulnerable from the rampaging batons and brutal knees of law enforcement, the rising seas of our unchecked appetites, and the pandemic’s Pandora’s box. Humbled as I am by the little creatures great and small who can take down my food supply in a New York minute, I’ll observe, listen, adapt, and remain faithful to the pursuit of balance.

May 12, 2020

Book, Food, Pandemic

These are the times that try foodies’ souls! Lines at food banks are stretching around the block at the same time that farmers are plowing under their crops. Seed companies are running low on product as wannabee home gardeners envision rows of sweet corn where crabgrass once ruled. Our favorite restaurants – hip, local, and fiercely independent – aren’t just not serving now, some may never serve again.

While events like these offend our individual sensibilities, the injustices revealed by the pandemic are deeply disturbing. Trump and his toady Republicans resist shoring up the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) even when it could do much more to relieve the suffering of hungry Americans (and over-stretched food banks). The coronavirus is extracting a disproportionately higher toll on people of color, not a surprise for those communities that have been on the receiving end of countless slights and indignities for ages. In my state of New Mexico, Native Americans who account for 10 percent of our population make up 53 percent of the state’s total coronavirus cases. Meatpacking plants, largely staffed by people of color and never the safest places to work even in the best of times, are getting decimated.

The pandemic is bashing holes in our food supply like a punch-drunk prizefighter. The rampage, which shows no immediate signs of ending, is breaking the industrial food system’s nose and opening gashes in its thin-skinned, unsustainable face. Like a poorly-equipped but determined militia, community food activists, food policy councils’, and regionally oriented producers and distributors are building a perimeter of defense in hopes that it can hold out until the cavalry – our cavalry, the one that is suppose to protect and serve everyone – can arrive. Some version of normalcy will be restored, no doubt, but will the “new boss [be the] same as the old boss” or, so “we don’t get fooled again,” will we use the chaos to build something sustainable and just out of the shell of the old?

Some of the answers to these questions can be found in the stories of the seven cities that I profile in my new book Food Town USA – Seven Unlikely Cities That Are Changing the Way We Eat. How cities like Bethlehem, PA, Boise, ID, and Sitka, AK have come together around their local and regional food systems offer numerous guideposts to those wanting to navigate their way to more resilient and just communities. Thanks to my non-profit publisher, Island Press, you can buy the book until June 15th at 30 percent off the list price. This offer applies to both the hardcover and e-book versions. Simply go to https://islandpress.org/books/food-town-usa and enter the promo code WINNE25. And for those of you who want to go all in with a signed copy of my book, send me a check for $25.00 or meet me on email (win5m@aol.com) to arrange use of a credit card. I’d be happy to sign and send you a freshly picked copy!

I can assure you that we will meet and laugh again at our favorite cafes and brew pubs. We will garden with joy once more, and we will hobnob at the farmers’ market, unmasked and smiling. We will learn new models of resilience and sustainability from each other. And we will pursue social and economic justice with a renewed and righteous resolve. Stay safe and keep the faith.

March 19, 2020

Love in the Time of Corona

We are now swamped by a microscopic virus whose backlit photos suggest an organism of luminous beauty rather than one of mass destruction. In a manner not unlike the “cocooning” that we employed during the aftershock of 9/11, we are told to self-quarantine, social distance, and shelter-in-place by public health folks whom we now lean on the way a drunk leans on a lamp post. During 9/11, almost 19 years ago, we watched in horror as a massive plume of black smoke carried the molecules of thousands of lost souls into the skies over metro New York City, soon to waft, serene as a host of angels, over the Atlantic Ocean. Clinging together desperately against the incomprehensible chaos, we never found an answer to our collective question of “why?” Many of us drowned in grief, some were shocked into silence, others marched off to the nearest military recruiting station like their grandfathers had in the days following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Lacking an obvious foe – Al Qaeda terrorists or Japanese militarists – we may be even more stunned by the onslaught of the coronavirus, today’s “enemy” whose source – metaphysical and physical – seems uncertain at best and against which we cannot send bombers or battalions of young men and women. Hunkering down, closing down, and cancelling all that propels our reason for living are anathema to our social natures which cry out for engagement, revenge, and reassertion of a dignity now denied by something absolutely unseen. Our leaders do their best to gird our loins for a passive war even when our first response is to attack, not to seek cover.

Standing down from the things we love in times of a pandemic – the company of others, good food and beverage, my eight now cancelled Spring speaking engagements – frustrates the pursuit of passions we hold dear. In Nobel prize winning author Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ Love in the Time of Cholera we recognize that the Spanish meaning for cholera (colera) is as much anger and passion as it is a disease. The novel’s characters struggle with overwhelming amorous feelings held against a backdrop of a country-consuming illness. As we navigate our way through a public health crisis not seen since the early days of the Aids/HIV epidemic, our success or failure this time around, as it was with 9/11, will rest on how we find new but challenging ways to love in the face of the indifferent disease.

Using her latex-gloved hand, the farmer gently moves my grasping paw away from the neatly stacked heads of lettuce. I realized this was no longer the good old farmers’ market days of picking through the bins or holding the apples up for inspection. The Santa Fe Farmers’ Market is now practicing safe shopping – instead of “pick your own” we’re now doing “you point, I’ll pick.” This Saturday’s winter market was missing one-third of its normal vendors and the crowd was down by that much as well. While people seemed a bit nervous – six feet distance between customers being impossible to maintain at a farmers’ market – they were happy to be there, reassured perhaps that some farmers were willing to show up. After all, we were more secure here than we would be at the area’s supermarkets whose aisles were packed to the gills with tense shoppers pushing bulging carts. There was no hoarding at the market, just soft murmurings between friends about those “local meals” they were making at home that evening since their favorite farm to table restaurant was closed for the duration.

And you never have to look too far to always find a tidbit of good news at the farmers’ market. Today’s was that the “Honey Man” was back after his successful rotator cuff surgery over the winter. Believe me, rumors were flying that his return was uncertain which is the kind of gossip that can send shock waves through the faithful. His reappearance alongside beautiful brown quarts of “Bucking Bee Honey” squelched the upsetting noise of rumormongers, thus stabilizing global honey markets, or at least the part of the globe that is Santa Fe. Remember, several farmers’ trucks and their goods were lost beneath the rubble of the World Trade Center on 9/11 while millions of dollars in lost market sales followed in its aftermath at the peak of the Northeast harvest season. Our support (and love) for farmers are as necessary now as then.

Your farmers’ market is just one of many small candles against the darkness. The mutual assistance initiatives cropping up like crocuses are another as neighbors and youth groups organize themselves to deliver food to those who must self-quarantine, or to form phone-trees that will conduct wellness checks. Keeping our farmers in business is obviously important, but so are the numerous other small businesses and individual entrepreneurs who are essential to our communities. One Santa Fe writer offered tips for how to keep a local, independent book store operational even though it must close its doors for now. Two things you can do, he suggested, are to buy coupons from the store now that can be used to make purchases in the future, and to order books directly from the store that they in turn will order for you from their suppliers.