Mark Winne's Blog, page 10

November 27, 2016

What I Learned from Idaho

“Work and learn in evil days, in insulted days, in days of debt and depression and calamity. Fight best in the shade of the cloud of arrows.” Ralph Waldo Emerson

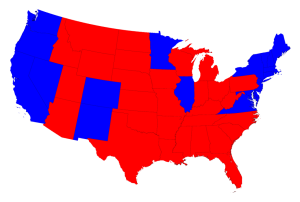

Despair set in about 3:00 a.m. Mountain Time as the states that were supposed to fade to blue flared finally to red. An hour or two of restless sleep became an exercise in futility as the consequences of a Trump victory detonated in my skull – demise of health insurance, the Wall, a Supreme Court packed with knuckle-dragging conservatives, coal-fired power plants and gas pipelines from sea to rising sea.

In the not-so-clear-light of day, W.B. Yeats’s oft quoted line came to mind: “The best lack all conviction while the worst are full of passionate intensity.” Whether the “worst” are Trump supporters is perhaps less important than what the “best” do next. To that end I want to share some convictions that I acquired recently from, of all places, Idaho.

To say that Idaho is a “red state” is, of course, an understatement. I think the TV networks called the state’s presidential vote for Trump before the polls even opened – after all, Idaho Democrats hold a none-too-robust 17 percent of the state legislature’s seats. Boise City Councilwoman Lauren McLean (Democrat) told me that when the council voted to ban plastic bags, the state legislature pre-empted municipal authority to make environmental regulations. The state legislature was more interested in upholding Idaho’s number-two ranking as the nation’s most “business friendly” state, and possibly surpassing number one ranked Utah.

There are many other Idaho-isms that don’t recommend it easily to progressives. For instance, it is one of the few states that still has a food tax. The Town of Greenleaf, less than an hour from Boise, garnered international acclaim in 2006 when its town council passed an ordinance “asking” all residents to keep firearms in the event that they might be overrun by refugees from Hurricane Katrina. Idaho is also home to the fast-food frozen French fry king, J.R. Simplot, and factory dairy farms that use up cows and the environment to churn out vast globules of processed cheese product.

So, what was I doing there? I had been invited to speak to the Idaho Hunger and Food Security Summit and to conduct a training for the state’s local food councils and coalitions. During that time, I got in front of about 300 food, farm and health activists, and much to my surprise, I came away with the strong impression that, in spite of Idaho’s iron-clad conservative credentials, the local food and food security movement is carving out some meaningful space for itself.

Local Food

The Boise area is a local food oasis with other Idaho towns and regions not far behind. There are excellent farm-to-table restaurants – check out State and Lemp Street in Boise or Horsewood in nearby Caldwell. Edible Idaho is chock full of stories and ads depicting a smorgasbord of local delights from the Boise Co-op to Idaho’s vodka (potatoes aren’t just for French fries). The Idaho Farmers’ Market Association coordinates 48 farmers’ markets around the state including a Boise mobile farmers’ market that makes 11 stops each week at sites serving seniors. Boise High School offers a progressive environmental curriculum that includes a well-tended student farm a few blocks from their main campus (the school also hosts a local food security summit every two years). On the day that I visited, teacher Ali Ward was directing about 30 shovel-bearing students preparing the soil for a winter cover crop planting (when not directing shovel-wielding young people, Ali plays band saw and washboard in a local band). And just in case you were worried that the state’s large Mormon community (24 percent of Idaho) might restrict alcohol access, local microbrews, wine, and several new hard cider labels, fueled by thousands of acres of nearby hops, vineyards, and orchards, tempt even the soberest citizens with tasting rooms and beer festivals.

(potatoes aren’t just for French fries). The Idaho Farmers’ Market Association coordinates 48 farmers’ markets around the state including a Boise mobile farmers’ market that makes 11 stops each week at sites serving seniors. Boise High School offers a progressive environmental curriculum that includes a well-tended student farm a few blocks from their main campus (the school also hosts a local food security summit every two years). On the day that I visited, teacher Ali Ward was directing about 30 shovel-bearing students preparing the soil for a winter cover crop planting (when not directing shovel-wielding young people, Ali plays band saw and washboard in a local band). And just in case you were worried that the state’s large Mormon community (24 percent of Idaho) might restrict alcohol access, local microbrews, wine, and several new hard cider labels, fueled by thousands of acres of nearby hops, vineyards, and orchards, tempt even the soberest citizens with tasting rooms and beer festivals.

Even the briefest of Idaho’s food scene tours would be incomplete without a tip of the hat to long-time food activist and farmer, Janie Burns. Starting in 1989 on her Canyon County farm with seven chickens and first-day-ever farmers’ market sales of $27, Janie has been growing food and raising animals while developing projects and raising a little Cain. She and her sidekick, local educator Susan Medlin, co-founded the Treasure Valley Food Coalition which has launched a number of initiatives, including the

“Tomato Independence Project.” This was a three-year community venture whose galvanizing slogan “End the tyranny of the tasteless tomato!” ignited a firestorm of enthusiasm for local food.

The project encouraged people to plant tomatoes everywhere – public as well as private spaces – take tomato-growing classes, save seeds, make sauce, celebrate “Tomato Tuesday,” read the book “Tomatoland,” and learn about the injustices that farmworkers face. Thousands of people got on board, especially when they hosted a “Bloody Mary” event that combined local tomato juice with, you guessed it, Idaho vodka! “The whole tomato project was the coalition’s way of showing people they don’t have to feel helpless when it comes to their food,” Susan told me.

More recently, the coalition has been running a series of forums on the loss of the Treasure Valley’s farmland, clearly an issue when red-state sensibilities clash with blue-state sensitivities. The roughly 30-by-100-mile valley’s beautiful, irrigated farms and deep bottomland soils are under siege from developers and an expanding home buyer appetite for still-moderately priced housing, a pleasant climate, and an endless horizon. Janie, who’s possessed of an elegant syntax, refers to all of this as “lovely sprawl” that’s filling Boise’s fringe with “upper-crusty, McMansion-nee” homes. Recognizing the current limits of Idaho food activism, she said, “There is a surge of interest in local food and food security, both from the public and the marketplace, [but] we all learned long ago to keep our heads off the skyline and avoid poking the bear.”

Food Security

As much as local IPAs and heirloom tomatoes improve my quality of life, they don’t do a lot to stem food insecurity. That is why the Idaho Hunger and Food Security Summit has held its biennial conference for the past 12 years. This year the one-day event delved into six broad topics ranging from anti-hunger advocacy to childhood nutrition to, yes, local food systems, which, interestingly, drew the most people. Protecting the programs that protect Idaho’s most vulnerable citizens, e.g., SNAP and child nutrition recipients, and recognizing the multiple values associated with local food are a high priority for a small but passionate crowd of Idaho food activists. Having decided to “poke the bear,” keynote speaker USDA Under Secretary Kevin Concannon told the audience we must have a higher minimum wage to reduce hunger. To make the link between local food and food security, Concannon proudly noted that 7,000 of the nation’s approximately 8,500 farmers’ markets accept SNAP.

As I was listening to the proceedings I couldn’t help but think of the town of Wilder, Idaho, that I visited on the previous day’s farm country tour. Nestled in the middle of ever-expanding hopyards and vineyards, Wilder is 76 percent Hispanic, has a 32 percent poverty rate, and 94 percent of its school children qualify for free- and reduced-price lunch (49 percent is the state average). In short, Wilder is one of the poorest towns in Idaho, and its residents are largely agricultural workers. Wilder’s residents are the foundation of Idaho’s booming farm economy, yet their children may never have the chance to leave the fields that literally surround them. As of now, their critical lifelines are federal food programs.

But food programs may not be Wilder’s first worry. If Trump follows through on his Draconian plan to deport undocumented immigrants, Idaho’s Hispanic community and agricultural businesses would suffer disproportionately to the rest of the nation. According to the Idaho Statesman (11/12/16), one-fourth of the state’s agricultural work force could be lost, and more important, children could be separated from their parents.

The Connection

Residents of Wilder may also work at the J.R. Simplot plant not more than 30 minutes away. But due to a technology overhaul, the potato processing plant went from about 1,000 workers to 185, leaving redundant workers with nothing but seasonal farm work. Ironically, the good food economy may begin to replace the not-so-good food economy. Chobani Greek Yogurt opened a new plant in 2012 in Twin Falls, Idaho, with the goal of employing 500 people (they did vacuum up about $55 million in public subsidies in the process). Hot on Chobani’s heels is the organic snack food giant Clif Bars, which is opening a $90 million facility, also in Twin Falls, that will employ 250 workers.

Food security advocates are joining forces with local foodies in the form of a Double-Up Food Bucks program (funded in part by the City of Boise) that is connecting SNAP recipients to 13 farmers’ markets around the state. Farm-to-school programs, lots of food and nutrition education from the University of Idaho Extension Service, and innovative gardening programs are bringing more of the state’s food vectors into alignment.

But perhaps the most telling connection was the Hunger Summit itself. By making the local food system a conference focus, bridges were built between different elements of Idaho’s food movement. As Janie Burns observed, “I suppose the best way to describe food work in Idaho is to compare it to a quilt. We are each still making our own little blocks and squares. Occasionally, we get to make new squares and even sew two together. [The Hunger Summit] was a great start to that effort.”

Lessons

If there was ever an excuse to drown my sorrows in locally produced alcohol, the morning of 11/9 was it. But I didn’t have a chance to indulge the urge. At 7:13 a.m. that morning I was on a train to the Albuquerque airport for a week’s worth of trainings. At the next stop, 40 rambunctious third graders, most of them Hispanic, climbed on board with a dozen teachers and chaperones and decided to sit in the car I had had virtually to myself. Their exuberance belied the previous night’s outcomes and the misery that enveloped me. Their giggling, optimistic presence reminded me that they are the future, but a future that may be circumscribed by a vicious border wall, and further diminished by rising seas and temperatures unless we adults “fight best in the shade of the cloud of arrows.”

To that end, I offer three prescriptions for these “insulted days.” First, prepare to resist the infrastructure construction that affronts our planet and our humanity. Walls do not good neighbors make, and pipelines only hasten the earth’s demise. Second, fight like hell to protect federal food programs from what is an all-but-certain attack. The biggest beneficiary of SNAP, school meals, and WIC are children. They could become the biggest losers. And lastly, seize upon the joy, community, and economic vibrancy available for the taking in our growing local food systems. Whether you’re in Berkeley, Boston, or Boise, partaking of the local feast is the gift that keeps on giving.

October 23, 2016

Kitchen Demolition

Great cooking utensils giveaway!

At some point in 2014 a momentous food event occurred. Unheralded by clanging church bells, it nevertheless signaled a pronounced shift in our eating behavior and a realignment of our culture’s tectonic plates. Precisely when and where no one knows for sure, but Americans started spending more of their total annual food dollars away from home than on food prepared at home. According to the USDA, American consumers paid 50.1 percent of their annual $1.458 trillion in food expenditures to others to do part or all of their food preparation for them.

Crossing that 50 percent threshold was inevitable. Since 1929 when we devoted 17 percent of our food dollars to “away food,” there has been a steady increase only slightly interrupted by economic downturns like the Great Recession. National economic prosperity can take credit for some of this decades-long growth, as well as the fact that Americans spend less as a percentage of their total income on food than any other nation. But there is something more afoot than our financial capacity to enjoy meals out, or increasingly, have them made, whole or in part, to be eaten in.

The time constraints imposed on us by our lifestyles and work drive us headlong into the welcoming arms of convenience eating. These are the conclusions that Karen Hamrick, Abigail Okrent, and Aylin Kumcu* came to in their research on household eating patterns. Yes, food costs dictate many of our food choices, but that effect is more on whether we eat at a low-priced fast-food eatery or high-end restaurant or a prepared, ready-to-eat-at-home meal or a meal-kit delivery service like Blue Apron. The more we work (and I would add, the more we work out) the less likely we are to use fresh and/or minimally processed food ingredients to make our own meals. Compressed timeframes impose stress, whether for the lower income mother trying to feed her children in between the two jobs she must work, or the yoga mom rushing to feed her children while still making her next session. Giving in to food out is how we increasingly choose to minimize stress that is sometimes externally imposed and other times self-imposed. Okrent’s surveys even found large percentages of people who actually claim they don’t eat meals as such because they snack all the time, mostly in their cars.

I get stress. As a newly divorced father in the early 1990s who had done pitifully little in the kitchen to contribute to my family’s daily meals, I was suddenly responsible for feeding two young children three days a week. As a man who could barely grill a burger, and as a food activist who touted healthy eating, I was clearly caught between a rock and a cast iron skillet.

My well used copy of “How to Cook Everything”.

After several failed dinner experiments that left my children ready to sue for an annulment to our joint custody agreement, I eventually found my way to Mark Bittman’s cookbook “How to Cook Everything.” With the aid of a future mate, I became a disciple of the minimalist doctrine of cooking that allowed me to prepare good-tasting meals with whole foods within 30 to 60 minutes. Salvation was at hand; a thousand more or less stress-free meals followed, and my children forgave me for being, in their words, “the only parent who never took us to a fast food restaurant.”

Okrent’s research also underscores the impact that advertising has on convenience eating, especially with fast food. A one percent increase in advertising drives up demand by 0.25 percent, which provides additional justification to limit advertising of unhealthy food as an obesity prevention strategy. But we’re not just talking about how many times a child is exposed to McDonald’s golden arches or the happiness awaiting them in a can of Coke.

Social media, while not explicitly a tool of the food industry, communicates through Millennials and other generations with a ferocious power and speed. When informed that the Korean taco truck will be at Hollywood and Vine at seven o’clock, you can be assured that the eager-to-connect under-forties will flock en masse. As yours truly pens this piece, Home Chef, Hello Fresh, and Blue Apron meal services are running sequential, competing ads on my Internet home page as every one of my keystrokes keeps their algorithms churning. And much to my dismay, I discovered that Amazon is using their/my Closing the Food Gap book page to advertise eMeals@Amazon (does that mean I get a cut of their revenues?).

Though the food industry has not necessarily written off Boomers, whose future food preferences will have more to do with what they can chew, Millennials are that next great mother lode that food entrepreneurs are salivating to mine. To that end, market researchers are slicing and dicing that generation’s every thought, action, and eating behavior. I learned from a number of articles and market surveys that Millennials (75 million strong) eat out more often than Gen X or Baby Boomers, want their food fresher, less processed, more organic, and chock full of ethics. They are very health conscious but straddling the fence when it comes to meat – some eating more, but more eating less – and when they do buy meat, they are more likely to buy it already prepared. And they are very busy.

I conducted my own “field research” by checking in with my favorite Millennial, Peter, my son. As a survey of one, he is a “convenience sample” that is presumably not biased by the approximately $100,000 of food I’ve purchased for him over the course of his 31-year life-span. Now that he’s a graduate student, he qualifies all of his comments with respect to the “empirical data,” but he offered the following qualitative statement: “With the foodie movement, people’s standards have gone up. [Millennials] are no longer OK…with spaghetti and a simple sauce. Since preparing a high-quality meal requires more time and skill…they are more likely to turn to the professional, e.g., food trucks and restaurants, to sate their higher tastes.” Interestingly, he also cited what he called the “Uber-ization of the marketplace” which he feels has reduced entry-barriers for numerous little food businesses, a trend he considers more democratic. He signed off the interview by telling me he had to hurry so he could buy the $11 “farm-to-table” salad before the food truck left.

Peter’s “Uber-ization of the marketplace” comment made me wonder about the proliferation of the home-delivered food industry (now worth $10 billion), which is bifurcated by the very large, decidedly non-democratic services, and the more populist “mom and pop” operations springing up everywhere. Two things disturb me. The first is that the “scaling to bigness” is starting to look like another manifestation of the “Wal-Mart-ization” of the home delivery industry – competition and capital leading to market dominance. The second is the “stressful lifestyle” message that all these businesses – big and small – are baiting their customers with.

In a promotional piece thinly disguised as an independent blog post for the meal-kit assembly giant Blue Apron (valued now at about $1 billion), someone called “Popdust” chortles on about how she/he was “stuck in a boring-dinner-rut,” and was always facing the “what should we have for dinner” question. The writer says, “I’m a foodie at heart, but I’m lost in the kitchen,” which doesn’t exactly fit my definition of a “foodie,” but whatever. Apparently, Blue Apron saved the writer – who admitted that “I work all the time” – because their recipes “never stressed me out.”

Blue Apron’s ability to settle our culinary angst may be purchased in the same way that similar warehouse operations often keep costs low: dangerous working conditions and low-paid workers. BuzzFeed News reports that workers at Blue Apron’s Bay-Area fulfillment center spoke of “low-paid workdays in a warehouse kept at below 40 degrees where fights routinely break out among co-workers…. Employees describe their hectic work as being ‘worse than an entire Black Friday at Best Buy.’” Local police have received “a dozen calls in the last five months that include everything from car theft to weapons threats.” And you thought your life was stressful!

Stress is the taut string that meal services love to pluck. Like the scab over our inadequacies, they pick at it, exposing a wound that only they can heal. Their advertising copy asks if “you dream of a personal chef cooking you (sic) healthy meals so you don’t have to,” and if you are “tired of wasting time at the grocery store.” They reinforce what they think you should aspire to: “a rewarding and busy day at work,” and pour salt into the wound by reminding you that you only have two hours after work to “pick up your daughter at ballet practice, get both kids showered, homework done, and dinner on the table.” And finally, they exploit fault lines in your marital relationship by asking if you expect your husband to cook. “Most likely not,” they respond, “He never really learned how and you don’t have time to teach him.”

I found some hope in the “mom and pop” enterprises sprouting across the landscape. Like farmers’ markets that gave us that home-grown, local alternative to the faceless chain supermarkets, some of these “democratized” and “Uber-fied” enterprises may be guided by less disempowering motives. I stumbled across one promising candidate in Columbia, South Carolina, where University of South Carolina nutritionist Trisha Mandes and her chef husband Eric Hoffman are in the final throes of opening Trisha’s Healthy Table, a vegan prepared-meal joint that will sell you healthy, take-out meals at a reasonable price. Plant-based, local food focused, and lovingly created by two loving Millennials, Trisha and Eric raised 20 grand on Kickstarter and are now going hell for kale to make their dream come true.

Trisha tells me that, “I don’t like the trend of people not cooking. I know female nutrition professors who don’t want to cook some nights, and their husbands don’t know how to cook. I hope that we can help people feel more confident about preparing healthy meals at home.” She notes that her market research included surveys that found individual and household stress as their biggest market driver. That is part of the reason she hopes to empower her customers with on-site cooking classes so that they, too, can learn to prepare tasty, vegan meals for their families. When I asked her if she was worried that cooking classes might undercut demand for her meals (priced at $11.99 each, you pick up at their site, and no tips), she replied, “Nope!”

I suspect that slouching somewhere in the data piles about where and what we eat lurks a deeper socio-economic malaise. For some, work is what keeps us alive even as it threatens to drown us. For those, the late night glare of the McDonald’s drive-thru is a beacon of hope in a very rough sea. For others, whose lives are defined by the pursuit of the perfect career, perfect children, and perfect self, food is a means to pleasure and health, but undervalued in comparison to an ever-ascending hierarchy of needs.

What I sense being lost in our respective personal and class struggles are the old kitchen and garden arts whose practice gives us the whiff of garlic minced on the cutting board, golden carrots grubbed from a small patch of earth, and a rambling chat with a farmer that goes on perhaps a little too long. Time has become our greatest oppressor. If we let it, the clock and our over-crowded field of wants and needs will suck the fluid from our souls leaving us like dried dates on a parched beach. It might be time to reassess what matters, and in the course of doing so, discover that time in the kitchen may be the best part of the day.

* As of this publication the USDA link to “US Households’ Demand for Convenience Foods” by Okrent and Kumcu is broken.

September 27, 2016

Fall Appearances and Other News

Crispy days and cool nights, the heady aroma of roasting chile peppers, and the whiff of magic markers and double-sided sticky tape must mean that the fall workshop season is upon us. As you can see below I’ll be journeying to the South, the West, and my former homes of Hartford and New Jersey. I’m looking forward to some good work and good company.

But first, let me share a thought, a recognition, and a site.

Unless your spaceship just landed at O’Hare from Mars, you probably know we’re in the middle of a tumultuous election year. Even though our two Presidential candidates haven’t talked much about food, that shouldn’t mean that we food citizens don’t ask our local candidates what they think about the pressing food issues of the day. Your choice of topics should of course reflect your immediate concerns, but cities, counties, and states are grappling with urban agriculture ordinances, access to healthy and affordable food, local procurement by schools and other public institutions, supplementing federal food programs, and land use planning that supports your region’s agriculture. Attend candidate forums, and preferably in sync with local groups like a food policy council, prepare some questions for the candidates on topics that potentially have the broadest possible impact for your community or state. Speak up, get loud, and let them know there is a growing constituency for good food for all. To paraphrase Goethe, food democracy is something we have to fight for everyday!

A tip of the hat to friend and colleague Emily Broad Leib who was recently named by Time magazine as one of “The 5 Most Innovative Women in Food and Drink.” As Director of the Harvard Food Law and Policy Clinic, she has led a mighty band of staff and law students to such diverse places as the hills of West Virginia, the Mississippi Delta, and the Navajo Nation to help reform the food-related laws, codes, ordinances, and regulations of those places. But what seized the attention of Time as well as Food and Wine Magazine, who put her in the top 20 list of Women in Food and Drink, was her work related to food date labeling and food waste. Through her discovery that food packaging expiration dates are not uniform, not based on law or regulation, and are generally meaningless, she has pushed the food industry toward more consistent labeling language that will probably result in reducing food waste by millions of tons. Though I’ve never known Emily to be a big eater or drinker, she is one heck of a nice person who, with her Harvard colleagues, uses her legal brilliance to achieve the most good for the most people. Congratulations, Emily!

And one more shout out for my pals at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. Through their Food Policy Networks Project, of which yours truly is a part time advisor, they have developed a website that does everything except heat up your cold pizza. At Food Policy Network you’ll find a directory of food policy councils, information about trainings and webinars, a listserv, and a resource database that is second to none. I dare anyone to tell me they couldn’t find what they need pertaining to food-related policies, assessments, economic development, production, food security, or waste!

October 3 – 5: Baltimore, Maryland – Working at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future

October 6: Virginia Food System Council Summit – Lynchburg, VA, 8:30 to 4:30. We will be leading a one-day conference on food issues in Virginia with the goal of setting an agenda for the Virginia Food System Coalition. There is still room so contact Allison Spain at allisonspain@virginiafoodsystemcouncil.org if you’d like to attend.

October 8: New Brunswick, New Jersey – Giving keynote and providing facilitation for the New Brunswick Food Planning Roundtable. Participation in the event is by invitation only.

October 28 and 29: Boise, Idaho – Giving presentation to the Idaho Hunger Summit on October 28 and leading a workshop on food policy and food policy councils on October 29. For more information, contact Eileen Stachowski at info@idahofma.org.

November 10 – 12: Hartford, Connecticut – Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group Annual Conference (NESAWG). Presenting a half-day course on local and state food policy on November 10, and a workshop on food policy councils on November 11. For more information, contact Tracy Lerman at tracy@nesawg.org.

Looking Ahead:

April 5 and 6: Youngstown, Ohio – Speaking at community forums on food and working with local food policy groups. For more information, contact Karen Schubert at Karen.schubert24@gmail.com.

August 14, 2016

Food Policy Amnesia

“I am quite sure that people only have the kind of government that their bellies crave.” From Paterson by William Carlos Williams

“I am quite sure that people only have the kind of government that their bellies crave.” From Paterson by William Carlos Williams

“Florida Lawns Are Being Transformed into Edible Farms,” gushed the Huffington Post (June 1, 2016) story about how a dozen Orlando, Florida homes had converted their manicured yards into tidy vegetable patches. Highlighted by sharp photos of well-tended rows of greens, the story explained how suburban sod had given way to salads planted and tended by a project called Fleet Farming. Homeowners mothballed their lawnmowers while getting a cut of the greens from their yards; earnest gardener volunteers had an outlet for their horticultural energy; and Fleet sold most of the food at farmers’ markets returning the proceeds to their coffers to finance future gardens.

Great idea, I thought, but why did it sound so familiar? Then I remembered a story I had read about a homeowner in Orlando who had been fined by the city for degrading that most sacred of American institutions, the front yard, by ripping out his grass and planting a 25-by-25-foot vegetable garden. As reported in the New York Times (“The Battlefront in the Front Yard,” 9/12), one Mr. Jason Helvenston was apparently in violation of section 60.207 of Orlando’s Land Development Code (not maintaining proper ground cover). He had gotten away with this vile deed for several months, presumably tending his tomatoes under cover of darkness to avoid capture, when a neighbor decided to bust him for his guerrilla gardening practices. Since the Huffington Post had made no reference to Mr. Helvenston’s dastardly deed or any history prior to Fleet Farming, I wondered what had transpired over three-and-a-half years to transform Orlando from a veritable Sodom and Gomorrah of home landscaping into a Garden of Eden?

Mary-Stewart Droege is a planner for the City of Orlando. Over the past few years I’ve had the occasional opportunity to work with her and some members of an area food coalition. I asked her why an activity that was previously illegal had found expression as a full-fledged and legally “out there” program? “The [City of Orlando] updated Landscape Code ordinance that addressed front yard garden came out of this [Helvenston] episode,” she told me. It’s this ordinance which explicitly allows home food production and cleared the way for the exciting venture that is now Fleet Farming. Mary-Stewart went on to say that, “We just submitted a USDA Farmers Market Promotion Program grant application to expand Fleet Farming into a low-moderate [income] community as part of a CSA model and to add more farmers’ markets.”

Orlando, like other cities, didn’t stop with efforts to revise outdated ordinances that had placed turf before turnips. Mary-Stewart said a chicken ordinance is poised to pass, fashioned after similar regulations that now treat microbreweries and small-scale food processing as home occupations. She said that newer policies are expected to come out of an Orange County Florida food assessment that will address food production, processing and distribution.

If you haven’t figured it out yet, the point of this little Orlando food history is to reassert the primacy of public policy in allowing good and creative food projects to take wing. Either the Huffington Post ran out of room or they simply didn’t get it. Cool stuff like Fleet Farming doesn’t just spring forth fully formed without a considerable amount of skid-greasing from city hall, usually aided and abetted by savvy food advocates and planners, and sometimes food revolutionaries like Jason Helvenston. Human memories are short and fragile things known to evaporate entirely when struck by the hot spotlight of a new food venture. But behind most small steps for food system progress lurks the shadow of public policy.

One would never know how important policy was strolling through the Santa Fe Farmers Market on a clear, sweet Saturday morning. But the fact is that the health, vigor, and happiness so abundantly on display, including the one hundred or so small farmers selling their goods, were purchased with the blood of a thousand policy skirmishes. Most of them were small and never saw the light of day. They were paper cuts that came in the form of a steady stream of city and state inspectors and bureaucrats hell-bent on shutting the market down with petty interpretations of regulations. Like the early Christians, farmers’ market organizers were chased annually by jack-booted private developers and public authorities from one garbage-strewn dirt lot to the next. When the City of Santa Fe and private foundations finally realized that the farmers’ market could be as big a tourist attraction as Georgia O’Keefe’s erotic flowers, it only took them ten years to raise the money to build what finally became a gorgeous market shed at the Old Railyard. Socially minded private entrepreneurship watered by good public policy leads to prosperity for all.

As thousands of food projects across the country began to soar, public policy actors who had once been foes were reborn as friends. A 2013 Michigan State University survey of how local government supports food system activities revealed that, from the 2,000 individual city and county respondents, there were an average of three food policies per respondent that supported such initiatives as better food access, community gardens, and farmers’ markets. In New Mexico’s case, once public policy officials recognized that farmers’ markets provide multiple benefits, funding by the New Mexico Legislature supported a robust Double Up Food Bucks program for the state’s farmers’ markets. And continuing the policy progression from local to state to federal, the New Mexico Association of Farmers’ Markets further enhanced the experience with a multi-year, multi-million dollar federal Food Insecurity Nutrition Initiative (FINI) grant.

Indeed, finding food policy synergy between all levels of government leverages more funding, more food projects, and more people served. In May of this year, the Los Angeles City Council agreed to prepare a local ordinance that will require all 57 farmers’ markets operating within the city limits to accept California’s Electronic Benefit Transfer card. This measure was vigorously supported by the LA Food Policy Council and local anti-hunger advocates. According to Jackie Rivera-Krouse with the Sustainable Economic Enterprises of Los Angeles , increased EBT access benefits both customers and farmers. “The farmers love it. It’s money at the end of the day,” she said.

Just to be clear, a federal program, often administered by a state agency, can benefit more people with healthier food and provide additional farm income when city food policy kicks in. Yes, making these connections, doing the research, and advocating for changes can be difficult and complex work – “transparency” and “government” are not necessarily kissing cousins. So when local food coalitions and councils tell me they don’t want to do food policy work – they don’t trust government, government bureaucracies are opaque, they prefer to do just projects – I can understand their frustration. That is when I urge them to not forget the food movement’s history nor dismiss the critical role that public policy plays, particularly at the local and state levels. “Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it,” is the quote famously ascribed to Edmund Burke. I would add that those who don’t even know that history exists are doomed to ride stationary bicycles going nowhere.

July 5, 2016

Roadkill Stew, Bad-ass Cabbage, and the Midnight Sun – Lessons from Alaska

The Alaska Airlines flight dips over Cook Inlet on its approach into Anchorage. The sunlight is reflecting off of distant glaciers and the cupcake glaze of snow-topped islands. My watch tells me it’s 10:30 p.m. but the midnight sun is as bright as a summer noon in New Mexico.

It’s easy this time of year to be drugged by the omnipresent sub-polar light and the glistening line of saw-toothed mountain peaks. Pretty soon, however, a food system guy like myself wonders how people get their food. Sure, my credit card bought me an sumptuous grilled salmon dinner, a fish so abundant in the surrounding waters that each Alaskan household is entitled to catch 25 big ones a year, provided you can endure standing in chest-deep, ice-cold water. So when the thermometer hits 20 below and the food barge is iced in; the weather is keeping bush pilots grounded and not able to service road less villages; milk is going for $9.00 a gallon and you’re salivating for some fresh greens; and yes, there’s wild game everywhere but you haven’t hit a live animal with a harpoon since that time you almost speared the assistant track coach with a wayward javelin toss, then what?

Alaska possesses more than its share of food system idiosyncrasies – a short growing season, beaucoup summer light, remote locations, and supply chains that stretch 4,000 miles to the lower 48 states. But in the course of talking with members of the Alaska Food Policy Council and other food system stakeholders, I began to wonder if Alaskan’s unique forms of adaptation held lessons for those in gentler climes. The relationship between resiliency and climate change, links between sustainability, non-renewable energy and the social welfare system, and the role that “wild” food plays in the state’s food system started to feel strangely prescient to me.

Tour de Farms

Moonstone Farm

If you want a first-hand look at Alaskan agriculture, sign on to a half-day trip with Alaska Farm Tours. If you also want to experience some poignant history, sign on to their Matanuska Valley Tour in Palmer, located about an hour northeast of Anchorage. The tour’s owner/operator is the feisty – and as of this June, very pregnant – Margaret Adsit, who also works for Alaska Farmland Trust. As such, she’s both knowledgeable and passionate about the state’s farm scene.

You’ll learn that 20 hours of daylight allows a cabbage to reach six-feet in diameter and concentrates the sugars in carrots to such a degree that it makes them insanely sweet. Think you have problems with raccoons or woodchucks? Try keeping a 1500-pound moose from eating her way through two-acres of vegetables. And while it stands to reason that Alaskans will use season extenders like hoop houses, the state’s farmers use more USDA high-tunnel subsidy funds than any other state in the country. (See Hodges and Meter Food in the Last Frontier).

In 1935 someone in FDR’s Emergency Relief Administration got the bright idea to relocate some of the Depression’s dispossessed farmers to the Matanuska Valley. Over 200 “volunteer” families from Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin said goodbye to their friends and took up residence in a place where they had been promised 40 acres, a house, and bulldozers to ready the glacier-carved forest land for farming. The land was there but nothing else. They were forced to live in tents and clear the land with horses. Within five years half of the families left their allotments, and by 1965 only 20 of the original families were still tilling the soil.

In spite of the hardships – and the unlikely prospect that the colonists would ever again vote for a Democrat – farms took root, some prospered, and today the Matanuska Valley is a little agricultural gem enveloped by a stunning ascension of snow-streaked mountains. We visited the last farm that is owned by a descendant of the original families, fifth-generation Don Church, who with his wife Michelle, operate Moonstone Farm. On a day as exquisite as the one I saw Moonstone, transfixed by a gun-metal grey peak that appeared to breach whale-like from the far end of a sweet little hay field, for a few dangerous moments I imagined myself homesteading in such a place. But when I heard how the plastic was ripped off the greenhouse hoops by the razor-like winter wind, how human eyes can freeze shut at 20 below, and that the catcher’s mitt-sized hoofs of a moose can turn rows of carefully nurtured vegetables into zucchini pulp, I quickly let go of the fantasy.

The Role of Subsistence

There are only 750 farms in Alaska. Even with the addition of a small portion of Alaska’s $4 billion commercial seafood catch (the vast majority is exported), Alaska must import over 90 percent of its food. In its premiere issue released this June Edible Alaska spotlights a farmer who uses float planes to transport goats, and another who must wait for high tide before he can motor his skiff filled to the gunwales with produce to market. Though gyrations like these don’t compensate for Alaska’s shortage of agricultural advantages, its ecosystem makes up for it by setting nature’s feast before those who can hunt, fish, and gather. “Wild food,” as it is called, is at the core of what Alaskans recognize as subsistence, which is defined by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence as the “customary and traditional uses of wild resources for food, clothing, [and] fuel…”

Roadkill Hare Stew. Photo courtesy of Marylynne Kostick

Marylynne Kostick, a soft-spoken research analyst with the Subsistence Division, gave me a tutorial on this complicated and contentious subject. Though blessed with the physique of a runway model, Marylynne’s skill sets suggest she’s more at home in the woods than in the fashion world. When she’s not preparing charts that explain the hunting breakdown between land and sea mammals, she devotes her free time to sun drying fish, rendering bear fat, and stretching moose hides. The accompanying photo of the beautiful bowl of food is actually “roadkill hare stew” which she explains is “another aspect of the ‘food system’ that shouldn’t be discounted. With so many wild drivers…and the hare population on an up cycle this year, the poor things are under attack…. Best to take them home and teach some kids to properly care for and inspect a wild animal.” (I later discovered that about 800 Alaskan moose die annually from collisions with motor vehicles. Groups have stepped up to remove, process, and distribute the meat from these poor critters to charitable feeding sites).

Through numbers and words, Marylynne makes it clear that “wild foods” are a critical part of rural Alaska’s diet. Taken together, she tells me, walrus, seal, whale, sea lions, moose, caribou, bears, Dall sheep, mountain goats and of course fish and shellfish, provide rural Alaskans (125,000 people or 17 percent of the state’s population) with an average of 189 percent of their protein and 26 percent of their caloric intake. The absence of any reliable pricing makes it difficult to determine the market value of this food, but using estimates of between $4 and $8 per pound, the range in 2012 was between $147 million and $295 million per year.

The conflicts surrounding wild foods stem from their dietary importance and a competition from non-subsistence uses such as sports hunting and commercial fishing. As Marylynne explained to me, a big part of her division’s job is to make recommendations to the state’s regulatory boards that will determine who can harvest what animal using which method, and where and when they can do it. Making the task even more difficult are federal subsistence regulations that further complicate the game of wildlife management. And in Alaska, subsistence users who are primarily Native Alaskan and rural have the highest claim, and as such “their rights would trump those of sports and commercial users,” in the event that the fish and game population dropped below subsistence levels. So far, this hasn’t happened.

$8.99 for a gallon of milk in Barrow, Alaska

But like the swelling chords of a cello that signal the approach of some dark force, Alaskans are starting to hear ominous notes of climate change floating ashore. While still somewhat anecdotal, those who gather wild berries, another favorite “wild food,” are reporting that the harvest of some varieties has moved 25 miles north due to warming temperatures. A species or two of fish common to more southerly waters are starting to appear off Alaska’s coast. And those who hunt walrus say it’s getting harder to do so due to the absence of ice floes on which the sea mammal perches.

In one curious twist on indigenous peoples’ cultural practices, food banks are becoming popular above the Arctic Circle, a region where the wild food harvest equals 438 pounds per person. Why? Native hunters have a spiritual connection to their prey. If the animal doesn’t “present itself” to the hunter, as if to say “I am allowing you to take me to feed your family” then the gun is not fired nor is the harpoon released. According to some people I spoke with, Native Alaskans may be turning away from subsistence hunting in favor of the food bank because it is “presenting itself” to the people in the same way that a hunted animal would.

Concerns arise as well around the future of Alaska’s limited farmland. Development pressure is keen and during the tour of the popular Matanuska Valley it became obvious where future housing would go – on farmland which is fetching $20,000 to $30,000 per acre.

Another potential fall from grace has been playing itself out in the state’s legislature this year. Since 1973 Alaskan residents have benefited from the creation of the Permanent Fund Dividend (PFD) which was the state’s way of sharing the North Slope’s oil wealth. Not only were state government’s coffers filled by the revenues, each Alaskan received an annual check averaging around $2,000. This wealth distribution scheme has been credited by some economists with giving Alaska a more equal wage distribution (less income inequality) than the rest of the U.S. However, state revenues have fallen precipitously in response to falling oil prices, plunging the state into a budget crisis, one that is likely to drastically reduce the PFD. The lesson, I suppose, is that what oil giveth, oil taketh away, to say nothing of what oil leaveth behind in the form of more carbon emissions.

Still, like everywhere else, the local food movement shines across Alaska bright as the midnight sun. Communities in this vast state are creatively maximizing their man-made and mother nature-made resources. The Alaska Food Policy Council has had success with legislative and administrative action to support the growth of their local food economy. There’s even been progress in social justice, not a field in which Alaska typically excels. According to Sarra Khlifi of the Alaska Food Coalition, a group affiliated with both the food policy council and the Food Bank of Alaska, the legislature this year suspended a lifetime ban on food stamp eligibility for convicted drug felons, surely a draconian measure if there ever was one.

How Alaska copes with its multiple food system vulnerabilities bears watching. Resiliency in the face of climate change will take on new and challenging dimensions in this highly exposed northern reach, not the least of which may be the hot, sweaty hordes escaping from the Lower 48. The lessons of oil, the lessons of subsistence, the lessons of the limits of human endurance, and the lessons of public policy that can be farsighted or shortsighted should not be ignored because they come from a place as remote as Alaska.

June 5, 2016

Appearances and Aperitifs

Early this spring it looked like I might have to lay off my booking agent and get a summer job. I got even more worried when I realized that my lifeguard certification expired in 1974, and that landscapers weren’t falling over themselves to hire the “aged.” Fortunately, a steady drip of speaking requests began to trickle in so that I was able to turn down that offer of a summer paper route.

A gander at my appearances below reveals that I’ll have to forego breathing at least one day a week to earn enough carbon credits to offset my flying schedule. The good news is that when I’m not standing at a podium or cursing the power point projector, I’ll have some time to enjoy the company of friends and family, the mountains of Alaska, the beaches of the Carolinas and Jersey, and two rambunctious American/British grandchildren.

But let’s first take a look at some updates and a new item or two.

University of California Riverside student Melina Reyes deserves our praise and heartfelt sympathies for her 115-hour hunger strike to draw attention to campus food insecurity throughout the UC System. My April 25th blog post (Ramen U: Is This the New Meal Plan?) highlighted the growing problem of hunger at our nation’s colleges and universities and took academic and elected officials to task for their anemic responses. I also suggested that students might want to do more than establish food banks by showing “a little rage.” I don’t know if Melina read my piece, but according to the campus newspaper,The Highlander, she called on the University’s Chancellor Kim Wilcox to “halt future tuition increases” and to “use (his) position as Chancellor to bring student food and basic needs insecurity to the public eye….” The Highlander also reported that fellow students were overwhelmingly supportive of both her and graduate student Michael Gomez for their initiative, “to the point that (she) cried from joy and appreciation” at a press conference. (The California State Assembly recently passed three bills that would assist hungry and homeless students.)

Looking for some summer food-flick fun? Allow me to put on my Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future hat and unabashedly recommend “Food Frontiers”. This is a 35-minute production of CLF’s in-house filmmakers Leo Horrigan and Michael Milli that takes you on a lively journey from the Big Orange (Southern California) to the Big Apple telling uplifting stories of healthy food access and education. From supermarket development (Philly), to farm-to-school (San Bernardino), to rural grocery stores (Cody, Nebraska – pop. 149), to cooking education (Austin), to urban farmers’ markets (NYC), to a “food is medicine” pediatrician (Virginia), you’ll get a healthy look at bright ideas, bright people, and a brighter food future for everyone.

For those who read my November 18, 2015 post “Eat the Rich for Thanksgiving” but haven’t been able to wade through Thomas Piketty’s 653-page “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” there’s good news. Various summaries, both print and e-versions, are available on-line (thanks to Michael Rozyne for pointing this out). My post includes a New Yorker quote from a Bernie Sanders campaign staffer who says, “I read a third of Piketty’s book. I don’t think Bernie would read a page of it.” I was reminded of this the other day when I heard a very smart food organizer say, “No one I work with reads; I can’t use more than two-minute videos.” And I remember feeling embarrassed in college when, on two occasions, I only had time to read the Cliffs Notes!

Last but not least, I want to give a shout-out to another book. It’s by newly-minted Ph.D. and Fulbright Scholar Alan R. Hunt, and the book is called “Civic Engagement in Food System Governance: A Comparative Perspective of American and British Local Food Movements (Routledge, 2015)” Now, academic titles like these don’t lend themselves to two-minute videos nor do they have Hollywood screaming for the movie rights. But what this book does do that others don’t (and let’s include films, blogs, Facebook, YouTube, Tweets, etc.) is to make it clear why food policy has only taken baby steps in this country. Hunt takes us on a well-documented journey through collaboration (and non-collaboration) among major elements of the food movement. He looks at the process on both sides of the Pond to reveal what’s worked, what hasn’t, and why. If you’ve ever wondered why America doesn’t have a national food policy, “Civic Engagement in Food System Governance” will provide you with many “Aha moments!”

Speaking of journeys, here are what mine look like over the next three months.

June 14 – 16: Anchorage, Alaska. Speaking at the University of Alaska and working with the Alaska Food Policy Council and local food policy councils. For more information, contact Elizabeth Hodges at ehodges4@uaa.alaska.edu.

June 22 and 23: Wake County (Raleigh), North Carolina. Speaking at the Wake County Food Summit (6/22) and the United Way of the Triangle (6/23). For more information, contact Erin White at erinsullivanwhite@gmail.com.

July 12 – 15: Baltimore, Maryland. Work with the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future and the Food Policy Networks Advisory Committee.

August 24 and 25: Columbia, South Carolina. Speaking at the South Carolina Food Access Summit and with the South Carolina Food Policy Council. For more information, contact Anna Hamilton at anna@sccommunityloanfund.org.

Late August – Early September: Uffington, England. Leading a seminar with Grandchildren Zoe and Brad. Topics include: The Importance of Make Believe in a World Gone Mad; Why Staying in the Lines of Your Coloring Book is Not a Recipe for Success; Twelve Ways to Assemble a Proper Peanut Butter and Jelly Sandwich; Why You Say “Tow-Mah-toe” and I Say “Two-May-toe.”

October 8 (date may change): New Brunswick, New Jersey. Speaking at the New Brunswick, New Jersey Food Summit. Date and location still to be confirmed.

Being on the road is hot and thirsty work. Please be in touch if you’d like to buy me a beer!

April 25, 2016

Ramen U: Is This the New Meal Plan?

My father was a business man and plastics engineer – World War II veteran, Eisenhower lover, and Fortune 500 executive. Over his morning cup of instant Nescafe and the New York Times, he’d growl at the newsprint that was inked only twenty miles east in mid-town Manhattan.

“Who’s job is this?” he’d ask, shaking his head at the latest domestic or international transgression to seize the headlines. “Certainly someone can fix this,” assuming that job descriptions existed for senior managers who could forge world peace, ensure victory on the battlefield, and redress the wrongs of the aggrieved. Even on his death bed, after the caring doctor told him he was dying, my father insisted through his medicated haze on seeing the person who could “fix this problem.” His insistence that a management solution existed for all of life’s events did not allow him to go gentle into that good night.

As I ponder the headlines on collegiate food insecurity and its attendant growth in campus food banks, I can’t help but feel like a chip off the old block. When I see that a survey of students in the California State University system found that 10 percent experience homelessness and another 23 percent “worry about hunger,” I ask whose job is it to fix this. When I read a piece by Clare Cady in The Chronicle of Higher Education (Feb. 28, 2016) that cited several campus food insecurity studies – a 2015 survey that found 20 percent of community-college students nationwide were experiencing hunger, that 59 percent of students at one midsize rural Oregon university were “at risk of going hungry,” and that 39 percent of City University of New York students were “similarly at risk” – I find myself screaming at an amorphous universe of technocrats who must be able to end this obscenity.

As long as I’ve been in the community food world, I must admit that I was shocked to discover college and university food banks. My first encounter came in 2012 at the University of Mississippi (“Ole Miss”). The professor who invited me to speak there was teaching a food course that required his students to undertake a joint project. Apparently in response to what they felt was a need for an on-campus emergency food program, the students chose to establish “The Ole Miss Food Bank”which opened its doors in November 2012. It’s website states that it is “a student and faculty led effort to alleviate hunger among students in the Ole Miss community. The mission of the Ole Miss Food Bank is to foster a healthy college community by providing nourishing food to students in need…The Ole Miss Food Bank will rely on the support of volunteers as well as donations.”

In an accompanying video, the University’s interim chancellor, Morris Stocks, says that it’s an “unfortunate reality that members of our Ole Miss community are food insecure.” Channeling my father’s rage, I say, “’Unfortunate reality,’ buddy? You’re the damn chancellor, why don’t you fix it?” Instead of offering a bold plan to reduce student debt (now at a staggering $1.2 trillion nationwide), offer more financial aid and a free meal plan to needy students, cut the football program’s budget (Heresy. Let the students eat Ramen!), and take on the elected officials who keep taxes low while tuitions remain high, the University sanctions the creation of a food bank! And decent students, loving their peers and fueled by a fervor to do good, stock the shelves with donated canned goods rather than occupy the Chancellor’s house.

During the course of a visit this past fall to Tennessee Tech University in Cookeville, I was given a tour of the TTU Food Pantry by Kaitlin Salyer, the project’s manager and a recent Tech graduate. Coincidentally, this food pantry began operation the same month and year as the one at Ole Miss. Since that time it has served about a thousand people.

The pantry’s physical space occupied a corner of a large community room located in a nondescript campus administration building. The food was mostly stored in what looked like a large, former cloakroom. Since there was no refrigeration, all the donated items were canned and packaged. Volunteers would fill emergency food bags from among these items, but a large pile of Ramen noodles stacked outside the storage space came with this sign: “Take as many as you want.” Though the pantry subsequently moved to a larger and somewhat homier space, it is still hard to imagine how their inventory would allow clients to comply with the TTU Food Pantry motto: “Eat Well. Do Well.”

It wasn’t until this tour that I became aware of just how widespread the college and university food bank movement had become. Kaitlin informed me of the existence of the College and University Food Bank Association (CFUBA) whose website describes it as “a professional organization consisting of campus-based programs focused on alleviating food insecurity, hunger, and poverty among college and university students in the United States.” When I reviewed their website at the end of 2015, they listed 240 college and university food bank members. As of April 2016, their member institutions have soared to 298, nearly a 25 percent increase in less than four months.

There is a striking similarity in how the campus food bank movement and the much larger U.S. food bank movement emerged. Starting with a relatively small number in the 1960s and 1970s, emergency food pantries grew rapidly in response to Reagan era social service cuts. They now number over 60,000, while the very large warehouse food banks have gone from 0 to over 200. As is the case with CUFBA, the evolution of local food banking required a national association, originally known as Second Harvest and eventually renamed Feeding America to provide further assistance, establish industry standards, and serve as a national voice for their members.

But more importantly, the similarities are reflected in each other’s language. We typically hear from both groups that, “food insecurity is an unfortunate reality,” that “the community comes together and volunteers to help others,” or in its more progressive frame, “we are doing what we can to connect our clients to services and programs like SNAP.”

What we rarely hear is any sense of authentic outrage, such as in a country as rich as ours’ no one should have to go to a food bank! Nor do we hear much in the way of shame or indignation from today’s college Presidents whose predecessors felt compelled during the Vietnam era to speak out against that senseless war, if for no other reason than to protect their students, their charges, their children, from a meaningless death.

One CUFBA member is Norwalk Community College in Connecticut. Community colleges and state universities make up a disproportionately large share of CUFBA’s members. This is not surprising since, as the above community college survey found, “one in five students have gone hungry at least once in the past 30 days due to lack of money.”

A statement on the Norwalk Community Foundation website provides a clear explanation as to why these numbers are so high: “Fifty-six percent of NCC students are the first in their family to attend college. Twenty-seven percent are parents. Only 33% can afford to attend full-time. Many of our students struggled or dropped out in other academic settings. It is a hard road and we want our NCC students to stay the course and graduate.” Which is why the Foundation does what it can to provide scholarship support.

It is also why the college established an on-campus food pantry. Rachel DiPietro, a 2012 Norwalk Community College graduate returned as an AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer to successfully perform that task. Her statement about why she did it paints a vivid portrait of what it means to be a student at a community college: “Every item makes a difference to someone—from the student who came in because she spent the night in her car and wanted to grab a toothbrush and toothpaste to feel more confident showing up to class, to the student who saves $60 a month by using the pantry, which has allowed him to work one less shift and study more.”

Leave Norwalk hugging the Connecticut shoreline along Interstate 95, and pretty soon you’ll run into Yale University. Better known for the number of world leaders it produces than the number of first in their family to attend college, Yale grows a $23.9 billion investment fund (2014) that generated a market-leading, mind boggling 13.9 percent per annum return over the past 20 years. NCC’s $27 million endowment puts it in the one-tenth of one percent category (of Yale’s endowment that is).

With sufficient resources to keep the future masters of the universe well-clothed and fed, Yale does not have a student food bank. It does, however, have a Real Food Challenge initiative that advocates for the purchase of food that expresses values of fairness, humane treatment of animals, sustainability, and economic justice for farmers and food chain workers. Yale is home to the Yale Sustainability Project and a student farm.

The University also has the distinction of being the place where the campus food revolution’s “shot heard ‘round the world” was fired when Alice Waters’ daughter entered the soon to be “renowned dining hall” of Berkeley College. Mom, it turns out, was not pleased with the common’s common fare, and proceeded to castigate, instigate, and agitate for what became the Yale Sustainable Dining Project. Having eaten one meal as a guest of Berkeley, I can only recall four or five meals in my life that surpassed it which is why I must agree with the college’s slogan: “Life tastes better in Berkeley!”

Am I suggesting that Yale and other institutions of its ilk take responsibility for “fixing” food insecurity at Norwalk Community College, Tennessee Tech, Ole Miss, or any of the other nearly 300 CUFBA schools? While more powerful institutions speaking up for their less powerful brethren might be helpful, I could foresee a tangled list of reasons why direct forms of outside intervention may not be practical.

Maybe campus food insecurity is an issue that students themselves should own. While mobilizing their peers to get to the bottom of why some members of their generation are sleeping in cars may not be as sexy as convincing the dining service to offer free-range chicken, it may lead to solutions that strike at the heart of America’s most fundamental problems.

Perhaps student-led food organizations like Real Food Challenge can embrace a food action agenda that places student food security on the same level as the other standards for buying food that they are now working for across 200 campuses. California State University system has been one of the most positive respondents to the Real Food Challenge initiative, and it has now recognized the severity of food insecurity among its students. They seem willing and able to work for “real food” as well to make good food a reality for all their students. Anim Steel, Real Food Challenges Executive Director, told me in an email that “a CalState (sic) Real Food Challenge team is starting to develop proposals, and it’s likely at least some RFC affiliates will develop initiatives related to food insecurity on campus.”

There’s the making of a dangerous divide at America’s institutions of higher learning. One class of students are moving ever further up the food chain to meals that are so loaded with virtue that heaven itself is chagrined, while another class of students are left to bottom-feed on Ramen. Since this divide mirrors the even greater income and wealth disparities of American society, campus food insecurity will not be resolved by starting more food pantries. But just as younger children must pass their school days adequately nourished to ensure their readiness to learn, we must ensure that college and university students have the food resources they need to succeed. Until the policies of America’s political system shrink the nation’s income and wealth divide, we all have a responsibility to “fix” food insecurity on our college and university campuses. And if it means showing a little rage, so be it!

March 20, 2016

Global Warming and Poverty: Can We Find Common Ground?

In spite of what climate change deniers say, science tells us that the earth is warming. The seas will rise, extreme weather will become the norm, and our crocuses will bloom in January.

In spite of what climate change deniers say, science tells us that the earth is warming. The seas will rise, extreme weather will become the norm, and our crocuses will bloom in January.

For those of us with means, the immediate adjustments may only require that we place our blanket a little higher up the sand dunes when visiting the beach, or crank our air conditioners up a notch to stay comfortable. But for those whose lives are defined by poverty or near-poverty – who struggle to pay the rent, put food on the table, and keep that 15-year old car on the road – warming temperatures will mean higher utility and grocery bills as well as more health-related complications. Not only will the poor sweat more, they’ll pay more.

My daughter was the first one to alert me to the impacts of environmental injustice almost 20 years ago. She was shopping around for a college thesis topic and came across studies of river communities where it was the norm for low-income families to own or rent homes in the flood plains. Naturally, these were the cheapest locations. When those rivers flooded, as they invariably would every 50, 20, or even 10 years, guess whose homes were the first to be wiped out? And as you might imagine, the proverbial mansion on the hill was always spared.

Though the periods covered by these studies preceded climate change in the sense that we discuss it today, they point to a logical and historical pattern of human settlement and community growth. The high ground, the scenic (unpolluted) vistas, the fertile soil, and more recently the swank, in-town condos with easy access to Whole Foods, were occupied by the more affluent. The eroded and overgrazed hillsides, the vacant spaces along the railroad tracks, and the corridors downwind from the incinerator were consigned to the poor. It’s a proud American tradition, with obvious European roots, that them that has gets, while those that don’t get what’s left, which usually ain’t much.

Climate change adds yet another dimension to the age-old inequities that plague our civilization, which has, with little civility, turned up the heat. The evidence supporting the inevitability of rising temperatures and their adverse impact on lower income families is nearly irrefutable. In my home region of the Southwest, already America’s hottest, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency predicts that temperatures will rise between 3.5 and 9.5 degrees F. by the end of the century. And heat stress, already one of our leading causes of death, will only get worse for children, elderly, and those with fewer options to mitigate heat.

What are the consequences of climate change for our food supply? Some have surmised that warming temperatures will simply move warmer growing zones northward extending frost-free dates by weeks at either end of the growing season. But if heat stress is bad for people, it’s also bad for crops and livestock. According to the USDA, higher temperatures may hasten the growth of certain food plants, but if the fruit and seeds don’t mature at the same rate as the plant, crop yields actually decline. Grazing livestock, a major part of ranching in the West, will also suffer as pastures are reduced by drought and the loss of water to growing human populations. And don’t be fooled into believing that catastrophe is still a long way off – 2014 saw 60% of the U.S. land area enduring drought conditions.

If you think that agricultural science will save us by developing heat and drought tolerant crops, think again. The loss of farm and ranch land from development pressure, combined with increasing temperatures are likely to more than offset yield increases generated by innovative agricultural practices. Unless we act now to support regional farming and ranching – by protecting our agricultural lands and water resources, as well as strengthening urban farming – many regions of the country will only become more vulnerable to food scarcity.

Ultimately, climate change will drive up food prices. Tropical and semi-tropical countries will experience severe declines in food production putting more pressure on the U.S. to export food, while increasing the cost of the food it now imports. When combined with world population growth (the Southwest itself is projected to grow by 70 percent by 2050) food prices will rise. The poor, who already devote a higher share of their budgets to food than higher income groups will pay even more.

At a recent conference where I raised these issues, an audience member with the word “Vegan” emblazoned across her t-shirt in foot-high letters verbalized what she believed was the solution during the Q&A. Granted, eating more plants and fewer animal products would make a difference. The Union of Concerned Scientists has said that replacing 50 percent of animal product consumption with plants would reduce our water footprint by 30 percent. While I agreed with the vegan proponent, I am loathe to recommend that those who shop at discount stores, use SNAP, and fill their monthly food gap with food pantry donations also shoulder the burden of global warming. That’s the same dilemma rich nations face when asking developing nations to reduce their carbon emissions. We can’t expect low-income families to eat rice and beans any more than we can advise India to forego cars and return to oxcarts and bicycles.

A more imaginative approach that weaves together responses to both global warming and poverty is called for. To that end the food movement is starting to embrace an agenda that not only builds a sustainable food system, but also has a meaningful impact on poverty. This is not easy to do, nor is it necessarily achieved when a local food project creates a handful of lower paying jobs. But advocates for local food, healthier eating, and better food access must make poverty reduction a part of their vision and engage in policies that, for instance, raise the minimum wage. Similarly, focusing on the community economic development impact of a more localized food system, particularly in lower income areas, can be an effective way to link these two massive issues.

A step in the right direction was suggested by a recent USDA survey that found that the farm to school initiative had produced a $789 million investment in local farmers and other food system stakeholders. While it’s not clear whether farm to school purchases have an impact on poverty, at least USDA is identifying the value of tying school food purchasing to local economic development.

As I’ve noted before, the Good Food Purchasing Program that was originally hatched by the Los Angeles Food Policy Council – and gaining ground in other cities, e.g. Austin, Texas, make community economic development and sound labor practices important criteria in vendor selection for public procurement.

A series of case studies that look at the role local government can play in promoting local food, sustainability and more just economies offer examples of how communities can better integrate climate and poverty concerns. And on a regional scale, A New England Food Vision presents a bold plan for food self-sufficiency that places economic justice at the center of the plate.

The mayor of my own little burg of Santa Fe has stepped up with a plan he calls the Verde Fund which will be going to the city council in a few weeks (our food policy council is scheduled to endorse it). The proposal will put public funds to work creating jobs, strengthening and expanding local food production, and ensuring that the city’s poor are not cast adrift as the temperatures rise. While the evidence is not sufficient at this stage to suggest that policies and programs like these will definitely lead to a resolution of poverty and global warming, what is at least clear is that more people are looking for common solutions.

The lack of a bold federal response doesn’t mean we have to sweat in silence. Programmatic action in lock step with local and state commitments can make a difference. Since doing nothing is not an option – and until brighter lights seize the reins in Washington – thinking globally and acting locally is our best strategy.

February 14, 2016

In Search of the Just Chicken

Once again I stand in awe of the challenges and opportunities presented by our complex food system. The hard work of bringing healthy, affordable food to everyone while adequately protecting everything and everybody along the food chain is not for sissies. We may make progress on one front just as new fronts open up all around us. And we may try to gather up all of the food system’s cats into our big, hairy arms only to watch them struggle free in petulant defiance.

Once again I stand in awe of the challenges and opportunities presented by our complex food system. The hard work of bringing healthy, affordable food to everyone while adequately protecting everything and everybody along the food chain is not for sissies. We may make progress on one front just as new fronts open up all around us. And we may try to gather up all of the food system’s cats into our big, hairy arms only to watch them struggle free in petulant defiance.

The ongoing urge to milk every ounce of goodness out of our food system while eliminating the bad reminds me of something F. Scott Fitzgerald once said, “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” In Los Angeles, good food advocates are aspiring to this higher level of intelligence as they try to implement the nation’s most comprehensive good-food procurement strategy.

Called the Good Food Purchasing Program (GFPP), the Los Angeles Food Policy Council and the Food Chain Workers Alliance want to go beyond the buy-local trend forged by the farm to school movement. According to the National Farm to School Network, over 40,000 schools nationwide are operating some form of farm to school program. But the City of Los Angeles and the L.A. Unified School District, which together serve over 750,000 meals a day, have set the bar several notches higher. They have embraced a procurement standard that includes local food sourcing, nutrition, animal welfare, economic development, environmental sustainability, and here’s the kicker, labor issues.

Over lunch on a balmy January day in L.A., Clare Fox, the FPC’s executive director told me, “The GFPP is the best of what food policy councils can do.” She stressed that “public procurement is a real food systems issue” because it directly addresses most of the key values that are increasingly driving food consumer choice. Fox and her colleagues shepherded the procurement plan through the large and organizationally complex food policy council, which literally engages hundreds of people and groups. Such a thorough vetting process ensured that these ambitious standards had widespread support.

Listening to Fox talk about the power of public procurement made me imagine a stroll down a grocery store aisle where I casually strike up a conversation with a red pepper. “Are you as nutritious and healthy as you look?” I ask him (“he” looked male to me). He proceeds to give me an impressive list of his nutrient content, their health benefits, and the agro-chemicals (or organic materials) used to grow him, including the ones that may have leached into waterways or harmed wildlife. To the annoyance of the neighboring avocadoes he continues in a rather animated fashion to tell me stories about where he’s from and how far he’s traveled to reach this store. His tale ends with the relationship he had with his harvester, who explained how much he was paid and the working conditions he labored under. Now try having the same conversation with the thousands of food items that an institution like the LAUSD must buy. If you’re successful and can then make informed purchasing decisions, you may very well have the whole wild food system by the tail!