Mark Winne's Blog, page 11

January 3, 2016

Brooklyn and Beyond

Brooklyn, New York

The blow to my head came out of nowhere. One moment I was turning down the bodega’s narrow  grocery aisle admiring the tidy merchandise display; the next thing I know I’m dazed and seeing stars. I look down at my outstretched hands holding the mangled frames of my eyeglasses and a case of Goya canned beans. “Dad, there’s blood on your face,” came the alarmed voice of my son who was giving me a tour of 5th Avenue in his Brooklyn neighborhood of Sunset Park. I dabbed at my right temple until my handkerchief was more red than white.

grocery aisle admiring the tidy merchandise display; the next thing I know I’m dazed and seeing stars. I look down at my outstretched hands holding the mangled frames of my eyeglasses and a case of Goya canned beans. “Dad, there’s blood on your face,” came the alarmed voice of my son who was giving me a tour of 5th Avenue in his Brooklyn neighborhood of Sunset Park. I dabbed at my right temple until my handkerchief was more red than white.

Why was I holding a case of beans, I wondered? The answer came from a chorus of Spanish voices, one of whom had been driving the dolly that collided with me. It was stacked so high with boxes he couldn’t see where he was going. With the instincts of an outfielder I had caught the full case as it flew from the dolly and ricocheted off my face. Apologies were not forthcoming, only a wad of paper towels from a clerk and fingers pointing the way to the “baño” to tend my wound. Such is the practice of emergency medicine Brooklyn-style when an earnest foodie is injured in the line of duty!

What had lured me into this shopper v. dolly incident in the first place was the stunning array of produce lining the sidewalks of 5th Avenue. Block after block of citrus, mangoes, and greens fronted stores abundant with attractive meat counters and shelves of non-perishables stacked to the ceiling in cramped spaces. The chatter and signs along the bustling sidewalks were Spanish, but three blocks east on 8th Avenue the food, signs, and chatter were Chinese. There, the street was redolent of seafood (some still panting), and bok choy tumbled out of every crate. If we had strolled downhill west of 5th Avenue to the waterfront, we would have encountered what my son described as a high-end, take-out food mecca frequented by Industry City’s hipsters and techies.

The cosmopolitan food experience (my glasses were repaired at “Cohen’s Fashion Optical” by its Chinese manager and his Latina assistant) can be disorienting and sometimes dangerous, but the pain can be worth the gain. Previously scarred by crime, this densely packed urban community had been possessed by what could only be described as a desolate food environment. Today, with the exception of an occasional flying bean box, it is safe and made vibrant by a dynamic food culture.

San Bernardino, California

How much can food heal? That question is being put to the test in San Bernardino, California where I arrived one day after the latest NRA-abetted shooting left 14 dead and dozens injured. Among the wounded was a county health official who had attended an earlier meeting of the San Bernardino Food Policy Advisory Council. I’ve reported before on the good work of the SBFPAC and the thriving and throbbing Huerta del Valle community farm in nearby Ontario. I’ve also shared my agony and anger in this space when similar events took the lives of 26 people in Newtown, Connecticut, the state where I lived for 25 years. While food can do little to mend the shattered lives of the victims’ family and friends, there may be food system threads that tie a community’s suffering to hope.

How much can food heal? That question is being put to the test in San Bernardino, California where I arrived one day after the latest NRA-abetted shooting left 14 dead and dozens injured. Among the wounded was a county health official who had attended an earlier meeting of the San Bernardino Food Policy Advisory Council. I’ve reported before on the good work of the SBFPAC and the thriving and throbbing Huerta del Valle community farm in nearby Ontario. I’ve also shared my agony and anger in this space when similar events took the lives of 26 people in Newtown, Connecticut, the state where I lived for 25 years. While food can do little to mend the shattered lives of the victims’ family and friends, there may be food system threads that tie a community’s suffering to hope.

The San Bernardino FPAC held its quarterly meeting on December 2, the day before the shooting, not far from the Inland Regional Center (shown here), the site of the rampage. The agenda reflected the plenitude and progress of the Council’s work including a robust discussion about how San Bernardino might adopt an innovative Orange County initiative called “Waste Not OC.” By using health inspectors to reach out to and educate restaurants and food retailers, Orange County is directing edible food away from landfills to sites that feed needy families.

To ramp up access to healthy food throughout the county (the nation’s largest by area), the FPAC, staffed and coordinated by the San Bernardino Community Action Partnership, has worked with dozens of food pantries to institute the Healthy Food Banking Wellness Policy. It has also spearheaded the expansion of summer meal sites across this region’s sprawling landscape. Over the past two years the results have been astounding. The food pantries now distribute over a million pounds of fresh produce compared to 170,000 pounds in 2013, and summer meal sites have grown from 87 to 197 in the same period. Writing of these achievements, Robin Ronkes from the County’s Department of Public Health said, “We are seeing remarkable results with the increased produce donations, supplying children and families with healthier foods.”

Reading between Ms. Ronkes’s lines, written two weeks after the shootings, I hear a tale of hope and resilience inspired by the work of thousands of hands and hearts. The county’s citizens are taking responsibility for the health and well-being of their neighbors. Good food, not weapons, will make communities like San Bernardino secure.

Jacksonville, Florida

Turning from the wild and wooly streets of Brooklyn and the broken hearts of San Bernardino,  I light for a moment on another place where food has become a gentle elixir. I had a chance a while back to visit the North Florida School of Special Education which provides exceptional academic, social and vocational improvement experiences for 146 people between the ages of 6 and 22 with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities.

I light for a moment on another place where food has become a gentle elixir. I had a chance a while back to visit the North Florida School of Special Education which provides exceptional academic, social and vocational improvement experiences for 146 people between the ages of 6 and 22 with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities.

The school is as special as its children and young adults. Distinctive classrooms, a full training kitchen, gardens, aquaponics and greenhouse facilities, and a food truck unite this joyful place around a philosophy that places food at the heart of the academic and developmental experience.

There is an occupational thrust that drives the program as well. According to Sally Hazelip, the school’s executive director, “we want our graduates to be employed one day in meaningful jobs, so they do part time work on site.” This ambition, as she later told me, is to avoid the kind of placement where intellectually disabled people often find themselves, e.g. bagging groceries at Publix. Her vision is that the school can turn a disability into an ability that provides a rewarding life for the graduate at the same time that they contribute to the life of their community.

A stroll around the three-acre campus (soon expanding to nine acres thanks to a recent land donation) clearly identifies that path. Berry Good Farm is the name given to the growing spaces that include raised beds (shown here) and low-tech, small-scale food production infrastructure. The farm was developed by its manager, Tim Armstrong, who was inspired and trained by the Food Revolution’s own Will Allen. Tilapia from two fish tanks find their way into the school’s Spring Fish Fry Fundraiser (about 20 percent of the school’s income is self-generated revenue). A food truck with food grown in the garden and prepared in the school’s culinary program makes its rounds to Jacksonville businesses, food truck courts, churches and private functions. And from seed to table, the school’s young people are cultivating, chopping, learning, selling, and earning their way into Jacksonville’s food system.

Healthy food is our understated salve. When forces we can’t control shatter our lives or disrupt our communities, it has the power to bring people and places together, and to return vibrancy and meaning to our existence. As we step briskly into 2016, let’s uphold the power of food to make us whole again.

November 18, 2015

Eat the Rich for Thanksgiving

I’m giving thanks this Thanksgiving for Thomas Piketty, the French economist and author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the much acclaimed tome on the subject of economic inequality. I acknowledge that giving over a portion of our national feast day to contemplate how the top ten percent of American wealth holders control 72 percent of the nation’s private capital (the top one percent control 35 percent) might make for unpleasant dinner conversation. But what better time to discuss our yawning wealth gap than when our charitable impulse beats strongest. As we are forced to dig a little deeper so that all may be fed, as we work a little harder to meet the demand for donated food that never shrinks, as we write yet another grant to support one more non-profit food program, the rich are reverently counting the steady accumulation of their financial blessings.

Consider a few simple facts. First, the rich get richer, generally through little effort of their own. As Mr. Piketty demonstrates with clear graphs that stretch back over 200 years, capital grows consistently at the rate of 4 to 5 percent annually. The bottom 50 percent of American wealth holders, by the way, control a paltry five percent of all private capital and benefit very little from their holdings.

The second fact is that we’re making little progress reducing domestic hunger and obesity. Blame whomever you want: the pack of guard dogs in the Republican Congress who defend financial privilege and the myth of “up-by-your-bootstraps” social progress, or the countless private and public food programs that feed people but do nothing to reduce poverty or inequality. Yes, there’s been a slight downward tick since the end of the Great Recession in food insecurity, now at 14 percent. Adult obesity owns 37 percent of all Americans. But remember, food insecurity in 2000 was 10 percent and adult obesity was 30 percent (it was at 13 percent in 1994).

These unfortunate numbers are largely due to the ever-growing pool of Americans who are needy and unable to find higher wage jobs. The earnings of nearly 100 million people are less than 185 percent of the national poverty level. This entitles almost one-third of the nation to some federal food programs such as SNAP, WIC, or school meals.

The depth of the escalating need for “free food” was revealed in a Feeding America survey of over 60,000 food pantry clients. The survey found that 54 percent of the respondents said they relied on food pantries as a regular source of their food, a situation that was never envisioned by the founders and managers of the nation’s emergency feeding network.

Recent mortality research by the 2015 Nobel Prize-winning economist, Angus Deaton, and his colleague, Anne Case, puts a tragic face on the declining fortunes of a growing class of Americans. They found a dramatic rise in death rates for middle-aged white U.S. males due largely to suicide, drug abuse, and physical pain. These growing rates were associated with low education and poor job prospects.

Hunger, bodies worn down before their time, self-abuse, ill health, and suicide are rife and rising in no-wage/low-wage America. But in the gated communities of Houston, Westchester County, and Silicon Valley, Ma and Pa sit comfortably at poolside deciding how many decimal points less than one percent of their wealth to dole out this season to their servants and favorite charities.

The hardcover edition of Capital in the Twenty-First Century is two inches thick and weighs more than a Thanksgiving meal with two helpings of pumpkin pie. After a year of dedicated reading, I notated nearly every one of the 577 pages of text and many of the 76 pages of footnotes (I’ve yet to pour over the online technical appendix that is also available). This labor of love was rendered largely painless by the Frenchman’s fluid prose (translation is courtesy of Arthur Goldhammer) and his consistent and successful efforts to render complicated economic subjects accessible to the educated lay reader.

Though the book’s physical density could stop a bullet on page 479, its importance in today’s economic climate makes it essential reading. This is why it was discouraging to hear my PhD son-in-law who works for a London financial trading firm tell me that he’d never have time to read a book like that. A recent New Yorker profile on Bernie Sanders quoted a close advisor to the Vermont Senator as saying, “I read a third of Piketty’s book. I don’t think Bernie would read a page of it.” My response is that sometimes you just got to bite the bullet and plow through books that explain how you’re getting screwed.

Here are a few of Mr. Piketty’s morsels to chew on this holiday season, morsels, by the way that were produced by some of the most comprehensive data gathering and number crunching in the annals of social science.

“When the rate of return on capital exceeds the rate of growth of output and income [as it does now] …capitalism automatically generates arbitrary and unsustainable inequalities.” No matter how smart and hard I work, those with large reserves of capital will continually pull ahead of me.

The top ten percent of U.S. income earners garnered 30 to 35 percent of all income in the 1970s. Today, they are taking down 45 to 50 percent of all income, a percentage that is probably higher since the growing use of tax havens makes it easier to conceal income. One reason for growing income inequality is the rise of so-called “super-managers,” primarily corporate CEOs and other high-ranking officers who receive out-sized compensation allegedly due to their out-sized skills, an assumption the Piketty does a good job of debunking. One thing that stands out about the rise of this richly rewarded class is that it started in the U.S. and remains much more common here than in Europe or elsewhere. And if there’s one thing that will scare the turkey stuffing out of you, it is that America’s income inequality is, “probably higher than in any other society at any time in the past, anywhere in the world.”

The consequences of income and wealth concentration are not limited to how many houses and yachts the one percent can buy. Keep in mind that just one percent of all adult Americans is 2.6 million people who can and do exercise a disproportionately large amount of social and political power. They and their elected representative keep taxes down, suppress the popular will’s urge to increase the minimum wage, and maintain a chokehold on the public purse.

One thing that Piketty makes clear, and which points the way to a reasonable solution (he likes to gently remind the reader that the size of inequality extant in the U.S. today has typically led to violent uprisings elsewhere in the past) is that the top “’1 percent’ who earn the most are not the same as the ‘1 percent’ who own the most.” The amount of private capital in this country is extraordinary, weighing in at four times the value of America’s annual gross domestic product of $14 trillion. That works out to about $56 trillion in private assets, a value that Capital persistently reminds us just keeps growing. To rein in this hungry monster – which is what must be done to reduce inequality – we need more than just a progressive income tax, and if you’re a low-wage worker, you need more than a significant increase in the minimum wage. We need, as Piketty makes abundantly clear, a tax on the capital itself, not just capital gains. The beauty of this approach is that a very small tax on capital, in the order of one percent of the assets held by the top ten percent, when applied to this monumental quantity of private wealth is capable of yielding about $400 billion annually for the public’s coffers. This isn’t even a financial haircut for the rich; think of it as not much more than a trimming of split ends.

Again, unless something of this order is done to curtail capital concentration, the gap will only grow. Yes, there are moments when major capital holders are caught in economic downturns, but ultimately capital accumulation, and the increase in the wealth gap, are like global warming: There will be some years that are colder than previous years, but ever hotter temperatures are a scientific certainty.

Why does this matter to those of us who toil in the world of food security and community food systems? Aren’t we just doing our bit to alleviate people’s suffering and to create alternatives to the industrial food system? Ultimately, I believe that most of us who do the myriad tasks that produce, distribute, and improve the quality of food want to win. For me, winning looks like substantially reducing food insecurity, diet-related illness, and the iron-grip of the industrial food system. Economic equality, progressive public spending, and a robust democracy will be required to win that game, but if the rules are determined by an elite who control an ever-expanding slice of the pie, we are bound to lose.

What I propose is this: First, Bernie, read the damn book (I’m sure Hillary has)! Reader, you should read it too, or at least some excerpts (the Introduction alone is immensely helpful). Make discussions of income and wealth inequality regular agenda items at your organization and faith community meetings. Consider what impact substantial new federal tax revenues and targeted expenditures would make in the lives of the people you serve (New York City Coalition Against Hunger’s Joel Berg has estimated we could end domestic hunger with additional annual expenditures of $40 to $50 billion). As candidates vie for political office over the coming year, force them to address the outrageous economic divide that threatens to sink our whole national ship. And over Thanksgiving dinner, as you break bread with family and friends and celebrate the equitable distribution of the harvest, take some time to talk about what this country might look like if we didn’t need food banks and soup kitchens anymore.

Just as Piketty says, “it is hard to imagine an economy and society that can continue functioning indefinitely with such extreme divergence between social groups,” it is hard for me to imagine a food movement functioning effectively without embracing the fight for far greater income and wealth equality.

September 27, 2015

A Blast from the Past, Mark Bittman, Fall Appearances and More!

I’m giving this edition of Mark’s food blog over to short stuff. No long, windy think pieces or rapturous reflections (oh well, maybe one). I just want to share a few things, including a look ahead at where I’m going over the next couple of months. I do this as much for folks who may want to catch up with me when I’m “in the neighborhood” as I do to remind myself where I am (or was, or will be).

First, for those who might have missed Mark Bittman’s departing essay in the 9/13/15 New York Times, the chef, writer, and food activist is pulling the plug on a great five-year run that popularized and underlined in red some of the day’s most important food issues. I like to tell people I met Mark exactly 14 years ago in a tent erected under a crystal clear September sky at the Jones Family Farm in Shelton, Connecticut. He had graciously agreed to join our first ever Celebration of Connecticut Farms and Food fundraiser, held only five days after 9/11. The event drew attention to other forces of darkness and evil that were paving over the state’s beautiful farmland. With Mark’s help and that of other chefs, farmers, activists, and dedicated volunteers, that event began the process of restoring vibrancy and meaning to Connecticut agriculture. From one Mark to another, I want to say thank you and God’s speed.

I also want to give a shout out to the National Farm to School Network http://www.farmtoschool.org/. These folks have played a huge role in making locally produced food a common item on school cafeteria trays across the nation. Boy, we’ve come a long way on that one, baby! When I suggested to Hartford’s school food service director back in the nineties that she buy Connecticut produce, she simply responded, “Why?” Thanks to NFSN and a growing army of determined soldiers, over 40,000, K-12 schools are buying $385 million of locally grown food annually for 23 million students. There are two ways to celebrate these achievements. First, October is “Farm to School Month” so make a big noise about it at your local school. And second, tell your members of Congress to support “The Farm to School Act” which will put more resources at the disposal of communities and schools to expand what by all measures is a successful way to help kids become healthier and help our local farms grow stronger.

Now this last item is a bit tricky. It just so happens that 40 years ago I and a band of teenagers started the Natick (Massachusetts) Community Farm, which is about 15 miles west of Boston. It was one of the first in what are now many community-based ventures designed to connect young people to food and farming (you can read more about it in my book Closing the Food Gap). However, the farm’s 40th anniversary would have completely escaped my notice if it wasn’t for the recent discovery of a videotape by one of its founding youth workers, Mary Ann LeLievre.

In 1975 we had secured a small grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, which, in its infinite wisdom, thought that the farm, then barely three months old, was a model youth project. The grant enabled a handful of the farm’s youth participants, including Mary Ann, to document that first year. Through the miracle of digital technology and the good work of the current Natick Community Farm staff (www.natickfarm.org), a dusty old plastic 8-track cassette is now “YouTube-ready.”

But first a warning: The slow moving nature of this 1975 production may not be suitable for people who suffer from short attention spans. Consult your physician before watching if you are prone to drowsiness when gazing upon pastoral scenes for more than 10 seconds, find blogs of over 300 words tedious, or experience ringing in the ears when listening to people with Boston accents. If you are fit enough to view this 23-minute film (feel free to skip around) then click on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tnCFiY3zfW0&feature=youtu.be. And if you can guess who the hairy young man is with the scraggily beard, you’ll receive a lifetime subscription to this e-magazine.

Now, to answer the question on everybody’s lips, “Where’s Mark?” here is a list of my fall appearances.

October 1 and 2 – Pittsburgh, PA – The Center for a Livable Future will be providing a training and briefing for members of the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council and City of Pittsburgh public officials. For more information contact Dawn Plummer at dmp37@psu.edu.

October 16 – Santa Fe, NM – Santa Fe and the Santa Fe Food Policy Council celebrate World Food Day with panels, demonstrations, and a locally inspired potluck dinner. For more information contact Morgan Day at morgan.g.day@gmail.com.

November 10 – Cincinnati, OH – A one-day training for the Greater Cincinnati Regional Food Policy Council. For more information contact Angie Carl at angie@greenumbrella.org.

November 12 -14 – Saratoga Springs, NY – Attending the Northeast Sustainable Agriculture (NESAWG) annual conference and presenting a workshop on November 13 on the role of community engagement and inclusivity in food policy councils. For more information go to www.nesawg.org.

November 16 – Harrisonburg, VA – Meeting with members of the Virginia Food System Council. For more information contact Mark Winne at win5m@aol.com.

November 17 – Tennessee Tech University, Cookeville, TN – As part of Tennessee Tech’s 100th Anniversary, I will be speaking and conducting seminars on campus. For more information contact Lachelle Norris LNorris@tntech.edu.

August 30, 2015

“Where Do People Around Here Get Their Groceries?”

After driving fo r more than an hour at 70 mph down an arrow straight country road in southwestern New Mexico, I was perplexed by the fact that not only had I seen so few homes, but I was still in the same county! In those beautiful, wide-open spaces where the cattle greatly outnumber the people, one doesn’t need a highly developed food consciousness to ask the question, “Where do people get their groceries?”

r more than an hour at 70 mph down an arrow straight country road in southwestern New Mexico, I was perplexed by the fact that not only had I seen so few homes, but I was still in the same county! In those beautiful, wide-open spaces where the cattle greatly outnumber the people, one doesn’t need a highly developed food consciousness to ask the question, “Where do people get their groceries?”

Food access, food insecurity and food production are concerns now being taken up by a growing number of food policy councils emerging across rural America. Though densely populated areas of the country face similar issues, the physics of time, distance, and human proximity present rural America with a decidedly different set of challenges. The four New Mexican counties that hug the Arizona and Mexican borders – Luna, Hidalgo, Grant, and Catron – where I journeyed recently contain a scant 62,000 people spread across 17,300 square miles. By comparison, the states of Maryland and Delaware have a combined 6.9 million people packed into 14,400 square miles.

There are consequences to living in places where people are few. In Luna County a Senior Meals on Wheels volunteer must drive for an entire day to deliver food to 12 separate homebound seniors. Residents of Catron County travel up to one-and-a-half hours to get to a full-service grocery store, while people living in Hidalgo County’s 3,000 square miles (bigger than Delaware) are only served by one supermarket.

It may be glib to say that rural America contains less of the good things and more of the bad things, but the numbers often suggest that story. Statewide, New Mexico’s metro areas have a poverty rate of 14.5 percent, but its rural areas are at 17.7 percent. Silver City, located in Grant County derives a dubious benefit from one of the largest open-pit mines in the world. While their well-paying mining jobs rise and fall with the price of copper, toxic residues carried in the form of air-borne particulate matter and groundwater pollution are persistent facts of life (and sometimes death). And due in large part to the paucity of many basic necessities and good work opportunities, rural areas are losing population, especially the young, and the remaining population is growing older and in need of more services.

But there are places in America that are even more rural than rural. Hundreds of counties, most of which are found west of the Mississippi River, also carry the designation of “Frontier.” Though it’s a term that evokes images from the Wild West, frontier status is based on criteria developed by academics and government agencies that identifies a place with very low population density. However, the criteria also includes abnormally long driving times to health services and commercial market areas. Suffice to say that frontier counties have the fewest people and the greatest gaps in the availability of goods and services. As one Grant County food activist put it, “Even our dumpsters have less food than other places.”

Fewer people per jurisdiction also translates into less political clout. Because the combined population of all U.S. frontier counties represents only two percent of the entire country’s voters, it goes without saying that the federal and state governments have to turn up their hearing aids to detect those distant voices.

Except for a small portion of Grant, all four counties that have joined together as the Southwest New Mexico Food Policy Council are frontier. This is a good part of the reason that the National Center for Frontier Communities, based in New Mexico, has provided “backbone” support for this regional coalition. The other big reason is simple political math – four low-population counties working together have more power and resources than any one of them alone.

The NCFC came into existence in 1997 to focus on the limited access to basic services in rural counties. But like many advocacy organizations, they soon realized that food deserts (the American Rural Sociological Society has identified over 800 rural food desert counties) were associated with poor health outcomes. This awareness eventually brought them squarely into the food system camp where they began exploring the multiple links between diets, agriculture, health, and declining rural economies.

According to Susan Wilger, NCFC’s Director of Programs, about a year’s worth of planning work with representatives from all four counties preceded the final development of the regional food policy council. “Fortunately, there was an existing council and agencies in all four counties who were interested in working together,” she told me.

About five years ago a coalition of groups working on health issues in Grant County received a three-year Robert Wood Johnson Foundation “Healthy Kids, Healthy Communities” grant. A portion of the funds and a significant amount of resources went into forming the Grant County Food Policy Council which operates under the auspices of county government. The Council’s experience and the wisdom of one of its founders, Alicia Edwards, also the Executive Director of The Volunteer Center, a Silver City non-profit food organization, gave the nascent regional food policy council lots of “lessons learned.”

A tour of the Center’s state-of-the-art community food facility makes it clear how important concrete projects like this are to the larger task of achieving regional food security. Complete with a half-acre of vegetable gardens, over 70 fruits trees, community meeting and kitchen space, and an emergency food pantry, the facility is also a reflection of deep community support. “Some amazing things happen in this city,” Alicia commented deflecting the spotlight back on the community. “If people believe in your work, they’ll support you.” (In that regard I was particularly struck by one act of small town charity from a clothing thrift-store called “Single Socks” which has donated over $188,000 to anti-hunger work in Grant County since 2009.)

Everyone, in effect, understands their role: The Center offers a wide range of helpful goods and services; the Grant County Food Policy Council works with County government to ensure supportive public policies (at the council’s urging, the board of county commissioners recently agreed to purchase a $150,000 chipper to aid the County’s composting initiative), and the Southwest New Mexico Food Policy Council harvests the power and resources of four counties to research regional needs and organize more effective advocacy strategies.

To illustrate how region-wide research and advocacy can work, Alicia tells me a story about food insecurity – rural style. On a monthly basis a truck loaded with donated food from the Road Runner Food Bank (New Mexico’s statewide food bank) literally pulls up to a wide spot on a Catron County road where 100 or more people have been waiting for up to three hours. Without the benefit of buildings or infrastructure of any kind, a local church group unloads the truck and distributes the food in the open to the waiting families. “How crazy is that?” says Alicia.

With that information and an in depth analysis of the region’s emergency food distribution system by the regional food policy council, groups are now trying to make improvements. More sites, better efficiency, and higher quality (healthier) food are the goals that collaborators are working toward.

“The handful of people doing stuff in Hidalgo County…are in this room”

You learn a lot about a place when you sit and listen to people tell their stories. This was certainly the case inside the Hidalgo County DUI Building, the June meeting site for the Southwest New Mexico Food Policy Council. Entering a public facility ominously named for those who violate New Mexico’s driving and drinking laws makes one feel a little uneasy. Though none of the county’s 5,000 residents know me, I pull my visor cap over my face, just in case. But once inside I am greeted by a beautiful potluck lunch of fajitas and happy (but sober) people, some of whom have driven an hour-and-a-half to attend the meeting.

Amidst the chatting and chewing, the meeting’s discussion told the tale of how people pull together to solve problems, not only because they want to but because they have no choice. Emily Shilling from the Southwest Council of Governments reminded everyone that the rates of food insecurity among children and elders in the region were increasing, and that obesity was a problem. While most people nodded their assent, Cristy Ortiz from the Hidalgo County Food Coalition pointed to the progress being made from expanded farmers’ market programs (e.g. “Double-Up Food Bucks” for SNAP recipients), new AmeriCorps volunteers, and better coordination between food pantries and schools, all of which had connections to public policy and/or the work of the food policy council. Michele Giese from the New Mexico Health Department attributed the region’s five new mobile food pantries (monthly emergency food drops like the one described above) to the work of the regional council.

Several public officials were present or represented. They included the offices of U.S. Senator Martin Heinrich and the City of Lordburg’s mayor. Hidalgo County Commissioner Darr Shannon, whose family has been ranching in the county for 125 years, was passionate about how much work needs to be done in Hidalgo. She reiterated the concern that “children here are going to bed hungry,” but reminded everyone that the “county’s roads and housing are in poor shape, and we have parts of the county without clean drinking water.”

Perhaps the most telling comment came from John Allen, a New Mexico State University Extension agent for Hidalgo County and a member of the Hidalgo Food Coalition and regional food policy council. Noting how challenging it is to work in low-density places, he said, “There’s really only a handful of people doing stuff in Hidalgo, and most of them are in this room,” gesturing to the 20 or so people seated at the table.

Yes, John was teaching some nutrition classes in the public schools, but the county does not have a single “farm to table” restaurant, and healthy food at any of the existing restaurants is almost non-existent. Yes, there were some large farms in the county, but most of them were producing hay and corn for New Mexico’s factory dairy farms, and it was difficult to get these farms to produce fruits and vegetables for local markets.

Rural places may not have enough people to do everything that needs to be done, but the people working on food and farming issues are strong, smart, and committed. By turning “smallness” to their advantage they are using their easier access to decision makers to cultivate more supportive policies and better collaborations. Linking health and food, for instance, has been a powerful marriage that is already bearing offspring. And to the extent that connection can find a partnership with economic development, the marriage can prove even more fruitful (the council is also conducting a food hub feasibility study).

But rural America has also learned that no matter how good their people are, they need help from the outside. Forging bonds with nearby counties, state advocates, and federal officials are the actions that will multiply their fewer hands many times over. The Southwest New Mexico Food Policy Council has done this by forming a regional council, working closely with the New Mexico Food and Agriculture Council, and building strong ties to federal officials.

Though the practice of self-reliance may be woven into the fabric of rural America, its residents know that by the time the cavalry arrives it could be all over. Food system and food policy work are excellent places to hone a community’s collaboration skills – the benefits come quickly and often with real impact. Attention should be given to building this capacity, which in today’s world is a critical survival skill.

August 2, 2015

Huerta del Valle – An Ontario Oasis

Huerta del Valle Gardeners

What is the sound of a woman’s hands slapping a corn tortilla into shape? Is it water falling over a rocky stream bed? Or a series of slaps across your face? No, my friends, I think it’s a doctor’s slap across a baby’s bum to remind it that life has begun. Yes, I think that’s it – a call to action, a signal that the simple perfection of your mother’s breast awaits.

The nurturing sound of human hands on food, and the arousing scent of sizzling, herbed-up fresh vegetables fill the pop-up shade canopies under which we sit. The summer sun is sinking just behind the compost pile massed at the western edge of Huerta del Valle, a community garden located in the flight path of the Ontario, California, airport. It is three-and-a-half acres packed with lush green plants and rainbow shades of produce, and it’s a place that ripples with a near-divine sense of community where the Spanish chatter of women is so sweet, so richly woven into the air around us, that it muffles the scream of landing jet planes.

Maria Alonso presides over Huerta del Valle with the countenance of a gentle priest – available, affable, affectionate; never insistent nor hovering. Though the daughter of a Mexican farming family, she always managed to find a hiding place whenever her father summoned her to the field. But like millions of parents of the past decades, it took a child with a health condition that might be remedied through diet to bring her enthusiastically back to the soil. In Maria’s case it was her ADHD son, and a doctor with the imagination to “prescribe” unprocessed, chemical-free food that changed Maria’s life. Lacking land and the means to buy retail organic food, she set about the task of organizing a community garden so she could “grow her own” and help others do the same.

The first site was on a piece of Ontario public school land that could only accommodate 15 gardeners. But Maria’s community of healthy food eaters was growing rapidly and needed something larger. Working with a very cooperative city planning department and the Healthy Ontario Collaborative, not only did Huerta find their current site, they found funding support from Kaiser Permanente and institutional support from nearby Pitzer College which, coincidentally, was also offering their students food justice courses.

The Pitzer connection would eventually bring money, produce sales, and eager volunteers to the bourgeoning Huerta project, but most importantly it brought a recent graduate, Arthur Levine. Arthur is Maria’s sidekick, confidant, and, as a fluent Spanish-speaker, sometimes translator. Brooklyn-born and bred, Arthur doesn’t have an agrarian background, but tells me, “My mother is a chef and a stay-at-home mom who taught me to love and value those who work in food, grow the food, cook the food and provide for the most necessary needs of life.” You could say this love found further expression in his growing passion for social and economic justice which “are amazing and worth fighting for,” not by smashing Wal-Mart, he assures me, but by “building the world we want to see, and that really works for everyone.” One might reasonably conclude that Arthur’s path to Huerta was pre-ordained.

Nestled into a densely packed, mostly Latino neighborhood of small, tidy homes, Huerta del Valle shares a border with a pleasant town park which is also home to a vibrant community center. However, I’m forced to lean closer to Maria so I can hear her over the roar of a descending Southwest 737. Giant commercial warehouses and the airport’s service industries dominate the neighborhood’s fringe. These structures are fed and disgorged by a constant convoy of trucks spewing diesel fumes on their way to and from nearby I-10. When the wind blows just right, petro-chemical odors from two plastic molding factories overwhelm the scent of the garden’s cilantro. Warehouse jobs – a source of many occupational injuries – and the construction industry’s ruthless quest to conquer California’s landscape with McMansions are the community’s primary employers. I guess this is what passes for affordable housing policy in America – we keep housing prices low with the help of environmental injustice.

It’s no surprise then that Maria’s community of friends, family, and neighborhood residents seek refuge at Huerta del Valle. They are not refugees fleeing an imminent threat so much as pilgrims seeking the joy of each other’s company and the earthly delights of a beautiful place. At present, 62 families tend garden plots (there are 15 families on a waiting list; it’s estimated that each family plot generates $15 a week in food savings). Two, half-acre plots are managed independently by three urban farmers – Andres, Eugenio, and Gonzalo – as part of Huerta’s effort to explore the commercial potential of urban farming. These small farming businesses are assisted by garden staff who market their harvest at three community farmers’ markets, one CSA, seven area restaurants and the Pitzer dining hall. That, plus several hundred volunteers, dozens of school groups, and assorted WWOOFers from as far away as China, Colombia, Austria, Germany, and Sweden make up what is a robust and multi-functional use of this peri-urban land.

Huerta’s numbers are as impressive as the bounty of its plots. Having seen more than my fair share of community gardening enterprises I would have to place this one at the very top of my qualitative and aesthetic ranking. But as I’ve said before, the most important word in community gardening is not gardening. And it is in the world of community building where Huerta definitely excels.

“This is my community,” Maria says to me in a loving, non-possessive way. “I hear from the gardeners all the time how the ‘garden makes us feel better,’ and that ‘I don’t feel depressed in the garden,’ and that ‘the garden is my family and my therapy.’” She goes on to relate one heart-wrenching tale of a woman who was leaving her abusive and heavy-drinking husband after 23 years, and who told her, “’I need change in my life, Maria. You can give me the power to change.’” Community organizer, gardening coach, and Mother Confessor are the skills Maria employs that nourish the garden far better than any fertilizer could.

As Huerta’s principal salesman, Arthur describes for me their unconventional marketing strategy, which consists of one part community engagement and what economists might loosely call the Robin Hood wealth redistribution model. “On Saturday morning the surrounding community can buy produce at the garden itself for $1 per pound; Pitzer College might buy the same produce at $2.50 per pound; and high-end restaurants may buy it for $4 per pound. I understood as well that there were one or two ‘elite buyers’ who were permitted to pay $8 per pound.

While this “pricing policy” might not fit the ideal of market-place transparency, everyone participating in this Ontario-based value chain seems happy with its values. From the family gardeners who donate their surplus to the “common marketing pool” to those at the top of the region’s food chain – including some very talented and progressive chefs – Huerta is creatively and collectively starting to generate a modest revenue stream.

But just because Maria and Arthur have strong community building and entrepreneurial instincts doesn’t mean they don’t also have to hunt for grant funding. The project’s start-up funds are diminishing, which have reduced Maria’s monthly stipend to only $1,100 for what amounts to a full-time job. Though the City of Ontario and Pitzer have been generous contributors – both in-kind and cash – Huerta del Valle recently submitted a grant application to USDA’s Community Food Projects grant program, which, if successful, would allow Huerta to fully set its sails. This might enable Maria to begin work on her vision of a “community garden every mile,” a beguiling concept that sites community gardens at one-mile intervals in a hub and spoke pattern radiating out from Huerta del Valle.

Feeling a bit over-fed by the loving attention of women who thought I wasn’t eating enough, I accept Arthur’s invitation of a guided garden tour. I’m escorted along 100 feet rows of purple basil and habaneros; kale whose productive life has extended across a southern California growing season from October of 2014 through this July; and long borders of stone-fruit trees, sunflowers, and melons. Competing herbal scents are everywhere; my eyes lavish attention on the ascending rows of horticultural perfection and the subtle shifting of green hues. But suddenly my Anglo ears are assaulted by a powerful blast of pulsating Latin music. Noting my startled look, Arthur assures me that everything is all right: “It’s six o’clock. That’s when Huerta’s Zumba class begins.”

Somewhere near the tomatoes, on an improvised workout platform of assembled wooden pallets, the hips, arms, and shoulders of a dozen women of all shapes and sizes are gyrating to an insistent, sensual beat. They are trying, with varying degrees of success, to follow the lead of their instructor, who’s urging her pupils on to ever greater exertions. I’m mesmerized by the motion and music, tempted to join in but ultimately restrained by a WASPish self-consciousness. Yet I’m suspended in the moment of what, by all accounts, is the essence of community, a place where love, health, physical activity, and an aching need to connect find union. Wouldn’t one of these every mile be the answer to most of life’s complications? While I contemplate an answer, I feel my hips start to sway; my taste buds relive the delights of a home-made, home-grown meal, and the California twilight fades to night.

July 15, 2015

Summer Appearances and Trainings

July 20 – 22 (2015) – Baltimore, Maryland – Center for a Livable Future at Johns Hopkins University. For more information contact Mark Winne at win5m@aol.com or (860) 558-8226.

July 23 – New Brunswick, New Jersey – Rutgers University – Community food system consultation. For more information contact Mark Winne.

August 18 and 19 – Lincoln, Nebraska – Aug. 18 at 7:00 PM – Presentation by Mark Winne followed by panel discussion – Unitarian Church in Lincoln. For more information contact Kathie Starkweather at the Center for Rural Affairs: Kathie@cfra.org. Aug. 19 – Food Policy Council Workshop by invitation only.

September 14 and 15 – Portland, Oregon – Closing the Hunger Gap Conference. Mark Winne and Anne Palmer from the Center for a Livable Future will present a one day food policy council pre-conference short course on September 14. This will be followed by a food policy workshop as part of the regular conference on September 15. Food policy council representatives and those interested in food policy councils from the Western United States are especially encouraged to attend. For more information about the course go to http://thehungergap.or/courses/. For conference registration information go to http://thehungergap.org/register/

June 30, 2015

The Daily Table: Is This What We Really Need?

The Daily Table in Dorchester, Massachusetts

There’s a new kid in town, who, like the new kid before him and the kid before her, is stirring things up. He’s saying things differently than those who preceded him, and his new ideas are making some people feel a little uncomfortable. In the parlance of the much-admired entrepreneurial class, he’s a “disruptor.”

The new kid is Dave Rauch, the former president of the beloved Trader Joe’s. His new idea is the Daily Table, a non-profit grocery store that opened in Dorchester, Massachusetts in early June. The Daily Table is located in a low-to-middle income area which has not enjoyed much success attracting conventional supermarkets. Relying largely on the donation of “seconds” – food that is edible and safe, but just beyond its expiration date or a few days shy of the compost pile – Daily Table is, according to CBS News, “on a mission to solve two problems: preventing tons of food from going to waste and offering healthy alternatives to families who may not be able to afford traditional stores.”

Read more: http://www.beaconbroadside.com/broadside/2015/06/the-daily-table-is-this-what-we-really-need.html

May 27, 2015

In Search of the Perfect BOD

I think I have a crush on Gretchen Morgenson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning financial editor for the New York Times. If I had to explain my attraction, it would probably be due to her dogged pursuit of fairness, a guiding principle that she believes will be achieved by a determined commitment to openness in all organizations and institutions, especially corporate boards of directors.

Ms. Morgenson’s “beat” is the murky world of for-profit corporate decision making where the practice of democracy is often akin to politically immature nations. In my fantasy date, I would ask her to consider the opaque world of non-profit boards of directors – one of my “beats” – where a generous infusion of transparency and sound decision making would benefit everyone, especially food movement groups.

By my count, I’ve organized, worked as staff to, or served as a member of at least 15 different non-profit boards. While there were definitely some high points – times when our group looked like a varsity rowing team dipping and pulling its oars as one – confusion and tangled paddles were more often the prevailing norms. Post-board meeting gatherings would find colleagues drowning their sorrows at the nearest watering hole. And over the years I’ve coaxed more than one colleague off a bridge after their most recent God-awful board encounter.

Consequently, I’ve often regarded attendance at non-profit BOD meetings in much the same way that I’ve approached a pennant-stretch Boston Red Sox game – great expectations swallowed up by abject despair. The questions I must ask, as I limp bloodied and battered into my dotage, was whether the pain of the board process was worth the gain for the organization; how can we do it differently, and how can we increase the chances that the next generation of community organizers and advocates gets it right?

In thinking about my perfect BOD, I reflected on a recent column by Ms. Morgenson http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/04/business/whole-foods-high-hurdle-for-investors-.html?_r=0 where she reminds us that “[S]hareholders own the companies they invest in, but they have long been…shut out…of naming…corporate directors.” She then trained her laser beam on Whole Food Markets, a leader in sustainable food merchandising, but a laggard in shareholder democracy. Whole Food’s management has refused to accept a proxy proposal that would allow shareholders with at least 3 percent of the company’s stock to nominate directors to the board. Like many corporations, Whole Foods only allows very large shareholders (count the number of fingers on one hand) to nominate directors. Many investors claim that restrictions like these maintain undue management control, contribute to exorbitant executive compensation, and reduce accountability. If one were to equate eating with democratic participation, it boils down to this: the few people with the biggest financial stake eat locally raised, grass-fed steak; those with smaller financial stakes eat feedlot hamburger; and the workers, community, and consumers eat the soggy leftover French fries.

You could say, “Nothing new here; welcome to the world of American capitalism!” But if you are in Germany, the corporate boards of directors consist of private investors, labor representatives, community interests, and even the public sector. The German state of Lower Saxony, for instance, owns 15% of the shares of Volkswagen and 20% of its voting rights; and that’s the world’s largest automobile manufacturer!

The question that has always plagued me about non-profit organizations is who “owns” them – the founding executive director who’s been there too long; the big donors and foundations; a few highly vocal board members? Or maybe they should be “owned” by the community whose purposes the non-profit supposedly serves. Perhaps the bar to receiving and retaining the highly coveted 501 (c) (3) designation by the IRS should be raised to where it requires a minimum percentage of representatives from certain stakeholder categories, e.g., low-income communities. Those with a significant interest in the organization should have a real ownership stake.

Whole Foods is fighting with the Securities Exchange Commission over this question of who can nominate directors in order to protect the privileges of the few over the rights of the many. They are fighting so vigorously that they postponed their annual meeting, originally scheduled for March, to this coming September giving their lawyers time to strike a deal with the shareholder rights insurgents. Stay tuned!

While not rising to the level of weaponized-management resistance displayed by Whole Foods, non-profits, especially those burdened with entrenched executive directors, have often worked unethically to purge board members they don’t like, and then maneuvered to bring in people who will be complacently loyal. Yes, the occasional gadfly will ask the hard questions like, “why isn’t the community we serve on the board?” or, “I don’t remember that new project you apparently have underway ever coming before the board for approval.” Responsible board members like these are usually put on the first trolley to Siberia.

More commonly, but with as much frustration as the challenges of board composition and control, is the question of board performance. Why is it that supposedly intelligent people who make complex decisions in their everyday lives dissolve into a pathetic puddle of drool when they meet to discuss the non-profit’s work? Yes, they are volunteers, but they would never countenance the sloppiness that too often characterizes their “volunteer work” in their own businesses or organizations. (The assumption that non-profit board members should not be paid, unlike their for-profit counterparts who usually receive generous compensation, is one that should be carefully re-examined. Maybe some kind of stipend would make people take their community responsibilities more seriously).

There are undoubtedly a thousand answers and remedies – please feel free to share yours – but my experience leads me to believe that an appalling lack of knowledge about group dynamics, process, and leadership is often the underlying cause of board dysfunction.

Recently I asked Brian Gunia, assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School, what he thought was the biggest problem afflicting group decision making. He told me, “Typically what you see is that people have very different understandings of the organization’s goal, which will later lead to conflict. The most important step is for everyone to explicitly and individually define the goal(s) that they believe the group is pursuing. It’s much better to deal with differences from the outset.”

We invest so little time – whether it’s at the beginning of our first term on the board or at a strategic planning session – in finding a clear and agreed upon reason for our organization’s existence that it’s only a matter of time before fault lines start to form. If each member truly “feels” the vision for the organization – in their gut and with some passion – and the goals are explicitly shared and articulated by everyone, then the organization will look more like that racing shell, oars sweeping gracefully across the water, silky and seamless in its movement.

The millions of non-profit organizations that are in, or could be in the vanguard for change owe it to themselves, their donors, and their constituents to have the highest performing boards possible. My two ideas for developing the perfect BOD are more transparency and stakeholder engagement, especially from their constituents; and more intentionality in defining and setting shared goals.

What are your tips, lessons, and ideas for creating the perfect BOD?

April 26, 2015

A Big Policy Moment is Upon US

For those of us who are buffeted daily by the shrill alerts that spill across our screens urging us to do this and do that, well, here’s another one: Before May 8th, go to http://www.myplatemyplanet.org/ and urge the U.S. secretaries of Health and Human Services and Agriculture to accept, in total, the recommendations of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC). This isn’t the Farm Bill; it’s not the Child Nutrition Bill; it’s not even Keystone; this is a blasé sounding report prepared by a panel of scientific experts whose collective wisdom will, if accepted by the secretaries, influence the physical health of every U.S. resident and the environmental health of our planet.

Why is this moment different and why does it matter? In a nutshell, acceptance of the guidelines and their eventual implementation will set the nutrition bar for SNAP, School Meals (30 million children), and WIC much higher than it is now. The “DGs” as I affectionately call them, which are reviewed and revised every five years based on the latest research, also effectively codify a standard of dietary behavior that may, over time, tame the raging bull of obesity that is currently trampling our nation’s young. Knowing what’s right to eat, as we know, doesn’t automatically change our food purchases, cooking practices, and lifestyle choices like physical activity. But the DGs sure give us a solid place to hang our hat when Big Sugar, Big Meat, and Big Fat tell us, “Ah shucks, folks, eat as much of us as you like ‘cause we ain’t gonna hurt ya.”

Except for a few food industry organizations like the National Pork Producers Council, whose president, Howard Hill, squealed that the advisory committee “was more interested in addressing what’s trendy among foodies,” there’s something in the DGs for everybody. Compared to past expert panels, this one chose to address questions of inequitable access to healthy food, dietary disparities between racial and ethnic groups (for instance, 29 percent of New Mexico’s Native Americans 3rd graders are obese compared to 13 percent of white 3rd graders), and the challenges to food security among lower income populations.

But what has set the air conditioners a rattlin’ at USDA and Farm Bureau offices was the DGs inclusion of that four-letter word – sustainability. The report says, “Meeting current and future food needs will depend on two concurrent approaches: altering individual and population dietary choices and patterns and developing agricultural and production practices that reduce environmental impacts and conserve resources….” I don’t care if the advisory panel was enjoying a little medical marijuana at the time they wrote these words, but a statement like this coming from a team of esteemed scientists is a great leap forward for humankind. While the Pork Producers may not feel this way, I was in hog heaven after seeing this report packed with so many goodies that it looked like a buffet table at an Italian wedding (perhaps not the best analogy in this case).

The sad news is that USDA Secretary Vilsack has already tipped his hand by signaling that he may reject the report’s sustainability language. As reported by the Wall Street Journal (3/11/15) his decision is likely to stick to his interpretation of the letter of the law, which he claims requires him to only focus on nutrition and dietary information. Not unexpectedly, Secretary Vilsack received a letter signed by 30 U.S. Senators, all but one of whom are Republican, that urged him to reject the recommendations that Americans cut back on their consumption of red and processed meats.

The Great Food Wars have been raging for decades across the finite real estate of the American stomach. As the DGAC makes it courageously clear, there is a lot at stake for everyone who eats, especially the vast majority of Americans whose health and well-being are severely compromised by their dietary choices. And with the inclusion of food production practices in the report, the DGAC has raised the stakes even higher by putting the future of the planet into play. While the nation’s farm bills and child nutrition bills have put hundreds of billions of dollars on the table, the Dietary Guidelines, without requesting a single dime of the taxpayers’ money, have also put the health of our citizens and the very future of our food supply on the table.

If you’re saying that you’re indifferent to the DG’s recommendations because you already make the right food choices, please think again. This is one of those cosmic occasions when astral bodies are in a state of perfect political, cultural, and scientific alignment that may not come again in our lifetime. This is when we are called to not only be good food consumers, but also to be good food citizens. So run, don’t walk, to your nearest communication device and, before May 8th, tell the powers-that-be that this country must take a stand for the health of this and future generations. Thank you.

March 30, 2015

A Rainbow of Farmers

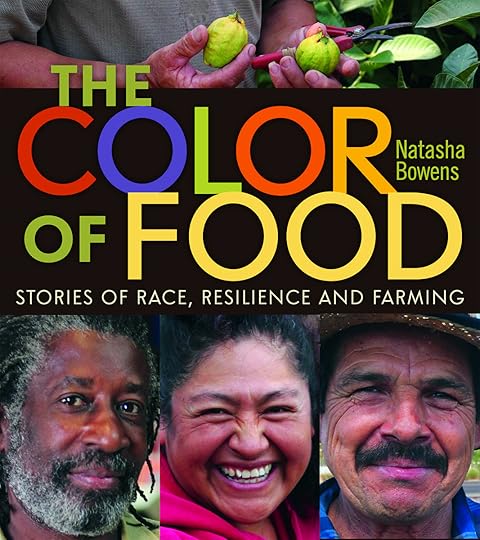

For those of us who still think that food is grown exclusively by 59-year-old white men wearing freshly laundered overalls and John Deere caps, photo-journalist Natasha Bowen’s book The Color of Food may come as a shock. In what can only be described as the classic existential American road trip, Bowens takes us from coast to coast in her trusty automobile “Lucille” in search of roots, farmers of color, and truths hidden in plain sight. Along the way we meet African-American, Latino, Native American, and Asian farmers – not a single one of whom fits any agricultural stereotype known to me.

For those of us who still think that food is grown exclusively by 59-year-old white men wearing freshly laundered overalls and John Deere caps, photo-journalist Natasha Bowen’s book The Color of Food may come as a shock. In what can only be described as the classic existential American road trip, Bowens takes us from coast to coast in her trusty automobile “Lucille” in search of roots, farmers of color, and truths hidden in plain sight. Along the way we meet African-American, Latino, Native American, and Asian farmers – not a single one of whom fits any agricultural stereotype known to me.

It’s a story that begins with a young woman of interracial heritage plunging her hands into the soil of a place where she found connection and community. Bowens could have stayed among her fellow communards, or as she put it, “back-to-the-land hipsters” honing her farming skills and adding to the growing bounty of locally produced food. But she chose instead to trade in the dirt ‘neath her nails for a laptop and camera to weave together stories about farmers of color. Her choice will no doubt inspire other young people to respond to their own inner agrarian.

The Color of Food is one of those well-written picture books that works at many levels. It is certainly America’s race story etched across a roughly textured agricultural landscape, where the oppression of 400 years finds contemporary expression. It’s also a tale of Bowens herself, who uses her camera lens to find her way through the lens of a conflicted past to a more hopeful future. It’s the story of places lost and places found, and how peoples ripped from their native lands have rediscovered their identities in new communities. And without a doubt, it’s a tale of the suffocating blanket of the industrial food system and its uncanny ability to suck the life from our souls.

One of Bowens’ gift to us is Daniel Whitaker, a black 93-year-old retired hog farmer from North Carolina, who gives a verbatim account of the medieval practice of sharecropping. “We would make 10 cents a day…but that was the way it was,” he tells us. “Your parents would work all the year and the opposite people [his almost childlike term for white people] would…tell you, ‘you didn’t earn any money this year.’ Those things rested hard on my mind….I knew I wanted to do something different.” And he did just that, clawing his way to the purchase of 314 acres of land where he successfully raised hogs and grew peaches, apples, pears, and corn. Mr. Whitaker passed in 2014.

Fortunately, Bowens is not one of those writers eager to erect a pedestal before she knows who to put on it. She grasps her subjects intuitively and renders them in loving but carefully constructed frames. Her photographic images are strong, and she grants her subjects ample space to tell their stories in their own words. Bowen’s commentary provides just enough connective tissue to maintain an even narrative flow, and enough context so that we can easily see the big picture.

And of course there’s never any doubt which way Bowens’ compass needle points. Leading us into the future with the book’s final chapter, “Generation Rising,” Bowens’ issues what might be read as her generation’s agro-ecological manifesto: “We refuse to settle for anything less than transformation and what we think is just. My hope is that this willpower…will truly revolutionize not only the food system, but the way we live on this planet.”

We see the embodiment of that will in the struggle of young, landless farmers of color Christina and Tahz Rivera-Chapman of Tierra Negra Farms. Experimenting with different forms of farming on various parcels of borrowed land, they cobble together a livelihood from off-farm jobs to sustain their burning desire to farm full time. Their frustration and growing rage becomes palpable when Christina speaks of trying to work “within the framework of money and capitalism – which we know is explicitly trying to screw one group over another.” But their frustrations with a system that doesn’t help beginning farmers has led them to an alternative plan to secure communally owned farmland. Their dream is to work with several young farmers of color to collectively pursue common agricultural goals while also forging bonds between generations of farmers.

Though I believe that a healthy dose of subjectivity is sometimes necessary to ensure a writer’s objectivity, I did find myself bridling at times over Bowens’ repetitious exuberance. Her too-frequent descents into diatribe as well as overstated assertions unrestrained by facts did leave me huffing and puffing on more than one occasion. But over time, I am sure, Bowens will learn to trust her pen and pictures sufficiently to let the reader find their own conclusions. In the meantime, one would have hoped that a strong editor might have curtailed the author’s excesses.

That being said, I will put aside my critic’s hat to state that we must listen to authentic rage, even when it is not filtered by analysis or supported by citations. It’s not always the absolute truth or the reliability of the data that matters, but the sense of truth as expressed by the speaker. Bowens courageously wades into territory that is heavily mined with emotion and scarred by some of the worst abuses in North American history. She should be praised for revealing the grace and resilience of the wounded and their children and the children of their children.

I found myself wondering out loud why, in the face of unrelenting oppression, that The Color of Food characters didn’t either run, or, running out of patience, stand and fight what would have been a suicidal battle. The only answer that makes sense to me is that the roots of farming go so deep into the land that they draw on enormous reservoirs of strength, and that the love of place is an instinct that can buffer us against the worst impulses of revenge. Bowens’ stories are first and foremost a triumph of humanity over racism, and a victory, related through numerous tales of pain and struggle, that we the alienated nomads of the 21st century might well heed.

Mark Winne's Blog

- Mark Winne's profile

- 5 followers