Mark Winne's Blog, page 3

August 27, 2023

West Virginia—When Teaspoons Are Not Enough

Almost Heaven, West Virginia

Blue Ridge Mountains, Shenandoah River

Life is old there, older than the trees

Younger than the mountains, growing like a breeze

Country roads, take me home

To the place I belong

West Virginia, mountain mama

Take me home, country roads.

Williamson, West Virginia Coal House — 65 tons of coal!

No one has done more to shape West Virginia’s mythology than the late John Denver. Today, the state’s “country roads” that the wide-grinned troubadour may have ambled down are largely interstates paid for by the American taxpayer and leveraged by the late Senator Robert C. Byrd, a master in his day of bringing home the bacon. To cruise at 65 miles per hour along one of these endlessly curving expanses of concrete and pavement, all of which seem to bear the senator’s name, is a rare driving experience. The sensation is one of maneuvering a Jetson’s TV aerocar from one mountainside to the next, soaring across precipitously steep gorges and hollows (pronounced “hollas” in these parts). Swerving from right to left and immediately back again, the chance to enjoy “almost heaven[ly]” scenery is sometimes denied by the concentration required to set up the next turn.

But the bacon of days gone by has lost its sizzle; in fact, past decades have not been kind to West Virginians. As the only state to lose a significant number of people in last US Census, those “country roads” are not taking their inhabitants “home.” Too frequently, they are conveying them out of state in search of more rewarding opportunities. Yes, the twisting by-ways bring in tourists who inhale the state’s breathtaking beauty and imbibe a bourgeoning outdoor recreation scene, but they also transport people in from far away who have succumbed to drug addiction and seek recovery in a place known as the epicenter of the nation’s opioid crisis. Just as the Sackler family is paying out billions for hooking millions on opioids, the crisis has spawned a large sub-industry of treatment and recovery services. As a result, John Denver’s “mountain mama” is not the rich warbling voice of the coal miner’s daughter, but the plaintive chorus of thousands of West Virginia grandmas forced into a second round of parenting. Called by their big hearts and a sober sense of duty, grandparents back in the hollas are caring for the children of their children—the victims of drugs, the drug industry, and a state economy that still leans on coal and chemicals the way a town drunk leans on a lamppost.

One such mama was the 75-year-old woman I met at a Williamson community forum sponsored by Facing Hunger Food Bank. She told the 20 or so of us gathered in a non-descript town building that she’s a retired school teacher now forced to work at Walmart to raise her three grandchildren because their mother was lost to drugs. “It’s an epidemic out there!” she told the group, noting that with these additional responsibilities, “I can’t make ends meet because the foster care support is not enough.”

I found myself in Williamson, the county seat of Mingo County which shares a rugged border with eastern Kentucky, as one of many destinations on my 2023 summer road trip. The purposes of subjecting myself to nearly 5,000 miles of often-grueling driving was to see East Coast friends and families, take a break from New Mexico’s heat and drought, and immerse myself once again in my favorite question—what and who is responsible for the crucifixion of so many American communities, and what’s required to nurture their resurrection.

My map showed that it would be hard for me to miss West Virginia. After a consultation with Dr. Joshua Lohnes, who oversees the Food Justice Lab at West Virginia University and is part of a team that directs the state’s SNAP-ED initiative, I was told that the state’s southwestern Appalachian region has all the fuel I need to fire my curiosity. “These are resource-extraction (coal mining) communities where people feel disempowered by structural economic forces,” he told me, “It’s where people are pushing through those challenges, surviving, and doing what they can do.”

The Williamson visit confirmed Josh’s assessment and then some. A drive through the town takes you by its one and only attraction: the world’s biggest (and maybe only) building made entirely of bituminous coal—65 tons of it. Embodied in that building is both the story of the region’s rise and former prosperity, and its decline and struggle to find a new identity. As coal mining employment declined—23,000 jobs in 2011 in West Virginia, 11,000 today—so has the population. Mingo County had over 47,000 people in the 1950s but only 23,000 in 2020. In the wake of coal’s demise and its well-paying union jobs, you’ll find a 30 percent poverty rate and, as one indication of the region’s overall poor physical health, an obesity rate of 38.5 percent and a 15 percent diabetes rates, among the highest in the nation.

The unofficial populist sentiment in these parts is that the blows to the state’s economy are the fault of Democratic administrations, singling out former-President Barack Obama and his Environmental Protection Administration for special scorn. When one round of coal mine closing notices was issued in 2014—including two shut-downs in Mingo County—a spokesperson for the West Virginia Coal Association blamed it on the “war on coal” orchestrated by President Barack Obama and the EPA. The truth of the matter is that aside from the global need to shift to cleaner and renewable sources of energy, coal’s decline is a function of the rise in natural gas and fracking, the decline in coal demand, especially as coal-fired power stations shut down, and the mechanization of coal mining methods—more mountaintop removal and open-pit mines mean fewer jobs.

The truth, however, is the first casualty for the miner who’s just been handed a pink-slip, and all he has to feed his family with are food stamps. With little doubt, this is why Barack Obama received only 8 percent of Mingo County’s vote in 2008, losing not only to McCain, but also to a convicted felon who ran as a write-in candidate. Overall, the fortunes of Democratic presidential candidates have tracked the coal industry’s decline. Bill Clinton took 52 percent of the West Virginia vote in 1996 compared to Joe Biden’s 30 percent showing against Trump’s 68 percent in 2020.

The voices in the Williamson community center echoed both the heartbreak and the hope of their economic malaise. When I read out loud the following statement from the Town of Williamson home page: “Williamson could have easily resigned itself to be a casualty of the decline in the industry [coal] that built it. But it’s proving it’s powered by an ever-greater energy source: a hopeful community,” I asked if people had read or even knew of the statement. Even though no one had, their reactions to it were shrouded in a curtain of despair that, when pulled back, offered a few reasons for optimism.

One young man who ran a home insulation business was chagrined by the hundred-plus abandoned houses in the small town of 3,000. From his work he knew that many seniors pay high energy bills because they live in poorly insulated homes (West Virginia is second only to Florida for its high percentage of seniors who make up the population). Jarrod Dean, the director of the town’s parks and recreation department was hopeful that a new committee on abandoned properties and the promise of state development funds might alleviate both problems.

Two representatives from the county school district shared that, due to the county’s dramatic population decline, the number of county schools had consolidated down from 30 to 9, and from 9000 students to 3,500. The “good news” was that all the schools qualified for a free, USDA lunch as well as a summer meal program that was currently serving about 600 kids a day. Erik Johnson, a community liaison specialist with Facing Hunger Food Bank (Facing Hunger Foodbank) pointed out that state funds were enabling the food bank to partner with all the schools to offer a weekend backpack program that provided enough food to sustain a child through the weekend. Additionally, the food bank ran a very popular “medically indicated food box” distribution every Wednesday in Williamson that customized the contents to the specific health and dietary needs of lower income seniors.

Limited broadband coverage and low literacy levels were cited as barriers to effective communication and community organizing. Lack of public transportation and the region’s notoriously winding roads reinforced the isolation of many communities and hindered the distribution of emergency food. And again, opioids and their multiple individual and community impacts were powerful undercurrents of everyday life.

Drug users and those in recovery—a visible presence about town—fell into one of three locally designated categories: “backpackers, walkers, or zombies,” referring to those who were either just arriving, in a recovery program, or totally zonked out. This is not the grinning “stoner” culture of my marijuana-using, Jerry Garcia blasting from the dorm room college days; this is humanity crippled, trapped in strands of rusty barbed-wire, crawling down a sidewalk like an injured cat seeking only a quiet place to die. This is where the cops carry naloxone, the antidote that can jumpstart the breathing of someone who has overdosed on opioids. It’s a place only two hours from Huntington, a community of 50,000 people which recorded 26 drug overdoses in one four-hour stretch in 2016.

Mingo is in a co-dependent economic relationship with four health facilities—two hospitals, one drug treatment facility, and one methadone clinic (with a 15 percent diabetes rate, drug treatment is not the only medical condition that sustains the region’s health care industry and hence the local economy). Drug use and its aftermath also send out seismic shock waves of collateral damage. Participants in our Williamson forum complained about the noise and chaos emanating constantly from subsidized apartments that are rented out to those in recovery. One woman in our group came to tears when she told us she had been adopted by her grandparents because her mother was opioid addicted. She said the emotional pain was exacerbated by the lack of family reunification services that might promote long-term healing.

In spite of a flood of troubles and challenges, mountain pride and persistence still prevail. Answers loomed, action was vigorously encouraged, villains were targeted, and a kind of faith against reason that their democratic institutions could still save them was proffered. Nathan Brown, a local attorney, Mingo County commissioner, and former West Virginia delegate (the designation for elected members of the legislature’s lower house), put the matter succinctly. “We got kids here who can’t afford to eat, but meanwhile, the state has a $2 billion budget surplus!” he told the group in a barely contained rage. “If the [State of West Virginia] doesn’t invest in this southwest region over the next 10 to 15 years, it will become a drag on the state’s entire economy.” To that end, Brown recommended that the state invest in the region’s infrastructure such as broad-band and roads. “The internet is just as important as water; it should be regulated like a public utility.” He emphasized that the state must also help the region become more attractive to private investment adding, “If we were good enough for the coal industry, we gotta be good enough for any industry,” he added with just a hint of irony. But spiffing up their look requires removing the physical blight (e.g., abandoned buildings) which, in his opinion, should include threatening jail time for absentee property owners who don’t take responsibility. Second, the region needs a drug-free workforce. “Businesses won’t locate here because they can’t find healthy, able-bodied workers,” he told everyone.

Interestingly, food and farming surfaced as one recipe for local change and economic growth. Jarrod Dean felt that agriculture could play a much larger role in diversifying the region’s economy. “We’re not even producing a small percentage of the food we eat in this state. Not only could we be developing high tech agriculture (e.g., greenhouses and hydroponics) to feed us, it could provide therapeutic and vocational opportunities for ‘second chancers’” he said, referring to those coming out of recovery and looking for work.

But the news that stirred the most attention—and kudos—was when Cyndi Kirkhart, Facing Hunger’s executive director, revealed plans to lease a 55,000 square-feet warehouse in Mingo County to distribute food to it and three adjoining counties. The warehouse will employ 15 people (a large number for one business in this region) and expedite food delivery to the area’s food pantries and other food distribution points. It will shorten the supply line from Facing Hunger’s current location in Huntington, a two-hour drive that is longer when winter turns the roads treacherous. Some of the new warehouse hires may be opioid users and/or convicted felons, both of which Facing Hunger has experience working with in job training situations.

It was generally known in the region and from sources I contacted in the state that Cyndi has taken the food bank in bold and innovative directions since she assumed the helm nine years ago. As a coal miner’s daughter herself, and with a psychology degree that led to work with the area’s most vulnerable adolescents, she hasn’t been afraid to make Facing Hunger a serious force for systemic change. Covering an unusual territory that serves 17 counties across three states (West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky), Facing Hunger sits at the center of Appalachia’s multiple maelstroms, including the economic decline that has pushed up demand for food but also made public and private resources harder to come by. “I’m paying for food now that we used to receive as donations,” Cyndi noted.

Against one of the most challenging socio-economic backdrops in the country, Cyndi and her staff are hoping to mobilize the community to address the underlying conditions of their hardships. “No more ramen!” is one mantra Cyndi is using to upgrade the nutritional quality of Facing Hunger’s offerings. Besides the medically indicated food box program, the food bank works with farmers, non-profit organizations, and multiple state agencies to stock and distribute as much locally produced and healthy food as possible. This includes a CSA program for seniors, and using the new warehouse in Mingo County to store area farmers’ produce, even if that food is not destined for food bank recipients.

When it comes to regional economic development, she sees numerous pathways starting with the most basic: “If people aren’t hungry, then they are more hopeful,” she said. But ever pragmatic, she convinced Senator Joe Manchin to bring home a slice of bacon for the hardest-hit part of his state. As a result, $1.5 million in Federal funds will be available to make the new warehouse facility operational, which both Cyndi and others see as a significant economic development tool.

But the most aggressive stance that Facing Hunger is taking is directed at the state’s policy makers. Meetings like the one she sponsored for me in Williamson are part of a larger regional organizing strategy that staffer Erik Johnson sees as a way to pry much needed resources out of state politicians. With 250-member food pantries in Facing Hunger’s region, there’s potential to galvanize the hurt and hopelessness of thousands of food recipients into a cacophony of demanding voices. Erik told me that, “Facing Hunger and its partners hope to bring 1,000 people to the state legislature during Hunger Day in January.” The plan is to shift the thinking of unresponsive conservative politicians, long the sycophants of the state’s coal and chemical industries, to meet people’s basic needs, diversify the economy, and make food and farming a central policy focus. As Cyndi told those at the Williamson forum, “We can’t be asking for teaspoons of assistance anymore when we need buckets of resources!”

Having not experienced many food banks that played such a dominant economic and community development role, I brought up Facing Hunger’s actions with West Virginia University’s Josh Lohnes. He said the states two food banks—the other one being Mountaineer Food Bank—are the biggest food hubs in the state. That makes them well-suited to not only address food insecurity but also assist local growers and other small and locally owned food businesses. In a similar vein, Josh has been exploring how nearly $1 billion in Federal food assistance (e.g., SNAP, WIC) that West Virginia receives annually could better leverage economic development in the food and agriculture sector. “Most of that money is now going to Walmart, Kroger’s, and Dollar General; over half of the state’s $500 million in SNAP dollars are going to big box stores. The impact of directing large amounts of those food purchases to the local food economy, including farmers and locally owned food businesses, could be immense.”

Strengthening the link between Federal food money and a state’s broader economic needs has certainly gained traction over the years nationally. The steady increase in USDA funding that incentivizes under-resourced people to buy and eat locally produced food, whether from schools, farmers’ markets, food hubs, or other food outlets, represents a significant—and welcomed—national policy shift. But Federal funds take on even greater meaning in West Virginia where, because of comparably high nutritional needs and low state resources, Federal food assistance represents about 15 percent of the state’s total budget. By contrast, if New York’s Senator Chuck Schumer secured a $1.5 million grant for some local project in his home state, the news would be greeted as a definite snoozer. When it’s done by Senator Manchin for Mingo County, the high school band suits up for a parade. “Because of the low investment in our communities by the state,” said Josh, “Federal money has a disproportionately greater impact.”

The same can be said for private philanthropic aide, another place where West Virginia comes up short. Having relatively few large foundations, there are not many places local food activists can turn for support other than local government, which can barely pay its own bills (Josh tells me about a food plan he worked on for a poor, rural county which desperately needed a mobile food pantry to reach isolated families. There was no way the county could help because their sheriff was in desperate need of a new car).

One notable exception, however, is the Pittsburgh-based Benedum Foundation which has distributed over half-a-billion dollars to West Virginia since World War Two. Recognizing, as others I spoke to did, the central role that food can play in so many facets of community life, the Benedum Foundation has targeted charitable food and farm projects with their giving. Signifying the priority they place on a food system model, their 2020 annual report was titled “Sowing the Seeds of Food Security” 2020-Annual-Report-Pandemic-Response.pdf (benedum.org)and highlighted numerous innovative food assistance and food development grantees. A few lines from that report are worth highlighting:

In 2006, the Benedum Foundation launched a decade-long strategy around the agricultural economy in West Virginia. This report reflects on that work, showing us all that food is a source of healing, an opportunity to train people in new skills, a connection to nature, and a way to give back to one’s community. Food affects every aspect of our lives. From heirloom vegetables… to Appalachian culture. It serves as an important economic connection between our urban and rural communities….Economic recovery depends on creating a viable support network for our food producers and providing families and children with access to the nutritious food they grow.

The industries that make up West Virginia’s glory days have seen better days, but their legacies of environmental degradation, hunger, poverty, and an Appalachian diaspora still pulse through the state’s veins. In spite of the fact that no one read the Williamson website’s paean to hope, the sons and daughters of the coal miners I met in Mingo County are making one hell of a goal-line stand. And if their state’s leaders drove with their eyes on the road ahead rather than on the rearview mirror, they would see the virtues of diversification, investing relentlessly—as in buckets, not teaspoons—in places struggling to remain alive, and roll out the red welcome carpet to young people. Leadership’s vision for the future should encompass a food and farm focus, not only because it meets today’s nutrition and economic needs, but because it presents a healthy and positive glow that can attract a new generation of bright, eager, and innovative minds to a state that is in sore need of young hearts and strong hands.

As the West Virginia portion of my 2023 Summer Road Trip continues, we’ll drive east over 125 miles of endless switchbacks—only 77 miles as the mountain bluebird flies—to Fayette County, West Virginia to see what a bright and shining future might look like. Stay tuned for Part Two!

July 9, 2023

Laredo Shows the Way to a Mending Wall

…Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.

“Mending Wall” by Robert Frost

Laredo, Texas is one of the more unique cities I have visited. Despite the fact that the Urban Dictionary defines the name as “a place you should leave,” or the weird YouTube video of a faux country cowboy singer sucking as much sentimentality out of its three syllables as he can, Laredo is a fast growing, Rio Grande flowing, border boogeying kind of place.

Celebrating the 268th year of its founding, Laredo is drenched in a rich Spanish/Mexican/US history about which most Americans are mostly clueless. That ignorance, when combined with its border location directly across the river from its Mexican sister city, Nuevo Laredo, sometimes turns this part of the world into a cauldron, to which the witches of the right add ingredients like eye of Newt, toe of Trump, and gall of Green. This venomous stew is then served up to the American public to heighten their fears. With their toil and trouble sown, the likes of Rep. Lauren Boebert, co-pilot with Rep. Margorie Taylor Greene of the Spaceship Looney-Tune, pronounced “President Biden’s negligence of duty has resulted in the surrender of operational control of the border to the complete and total control of foreign criminal cartels putting the lives of American citizens in jeopardy.” Heady stuff indeed, especially if any of it was true.

Without considering the source of this mischief, I too became anxious. Going to Laredo this past May for the second time in five years to work with the Laredo Food Policy Council, I wasn’t sure whether to have my bullet-proof vest dry-cleaned to take with me. With the expiration of the Trump perversion of Title 42, the news media projected that hordes of desperate immigrants would be flooding the “poorly protected” border. To the contrary, I arrived in Laredo to a scene of utter tranquility where even the Border Patrol looked bored. The only thing I was assaulted by was my Verizon international calling plan that hit me with an extra $10 a day charge, falsely insisting that I was in Mexico even though my hotel was a good 100 yards inside Texas.

When I asked Laredo City Councilwoman Melissa Cigarroa, a staunch anti-wall advocate, why there wasn’t more visible commotion, she immediately called the Republican assertions of chaos at the border “nonsense,” then offered that it was part of a Trump-inspired narrative that “Laredo is a dangerous place filled with dirty migrants crossing at will.” Viviana Frank-Franco, born in Mexico and a co-founder of both the Laredo Food Policy Council and the architecture firm Able City, was equally astonished when I asked her if the two-day food policy council conference might be cancelled. She promptly replied that “nothing is wrong; everything is quiet; it’s all a bunch of hype.”

The Border, NAFTA, and Many Trucks

Once a sleepy Texas town with a population in the tens of thousands, Laredo has exploded to about 270,000 today due to what is now the largest inland port in America annually channeling $227 billion in trade between Mexico and the U.S. Expected to climb well past 300,000 people over the next ten years, Laredo is coming to terms with the upside and downside of its growth as well as the all-pervasive border security industrial complex. Its binational status and vibrant cultural heritage offer endless life-enhancing possibilities, while its extreme climate issues like deep drought and withering heat (it’s 108 F. in Laredo as I’m writing this in late June) may alter life for the worse.

Once a sleepy Texas town with a population in the tens of thousands, Laredo has exploded to about 270,000 today due to what is now the largest inland port in America annually channeling $227 billion in trade between Mexico and the U.S. Expected to climb well past 300,000 people over the next ten years, Laredo is coming to terms with the upside and downside of its growth as well as the all-pervasive border security industrial complex. Its binational status and vibrant cultural heritage offer endless life-enhancing possibilities, while its extreme climate issues like deep drought and withering heat (it’s 108 F. in Laredo as I’m writing this in late June) may alter life for the worse.

In order to make Laredo an inland port—a product of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)—a multi-lane highway and bridge were constructed connecting Nuevo Laredo, Mexico to Laredo, Texas. Now known as Interstate 35, this transportation network, along with rail lines, conveys thousands of trucks a day right through the heart of the city.

Free-trade, as they say, is only “free” for the private companies that benefit from government subsidies, but very costly for those who are smack-dab in the path of its development. The massive infrastructure required to build the port blew away the homes of 390 Laredo residents who had the poor fortune of living in the way of “progress.” The belching diesels and other trade traffic leave a King Kong-size carbon footprint; much of the cargo passing in sight of Laredo neighborhoods is fresh produce from Mexican fields, none of which is available to the people who live there; and the border security with its lights, gates, and armed keepers suggest Checkpoint Charlie in the Cold War-divided city of Berlin where the U.S. faced off against the Soviet Union, not the friendly nation of Mexico. This present-day reality stands in stark contrast to what Frank recalls when she would cross the border frequently fifty years ago as a child: “We’d refer to it as ‘going to the other side.’ There was one border guard on the bridge who you smiled at and waved to.”

The Emerging Food System

In contrast to this rough and tumble economic growth, Laredo is progressively and thoughtfully nurturing a robust and more just food system, much-needed in light of the city’s high poverty rate (25 percent) and distressing diet-related health numbers. Set against its bustling inland port, Laredo is not only joining the urban trend of cool new coffee shops and boutique Japanese restaurants, it’s also raising up locally produced food as evidenced by a farmers’ market and young new farmers like Marcella Juarez; encouraging the development of micro-food businesses like @houseofbreadd which makes gluten-free/sugar-free baked goods; addressing the gaps in healthy, affordable food retail with the emerging Frontera Grocery Coop; and harnessing public policy for healthy change under the city’s dynamic, young new health department head, Dr. Richard Chamberlain.

During a panel discussion on the second day of the food policy council conference, Dr. Chamberlain, nattily attired in a sharp blue suit, highlighted by a pair of bright white fashion sneaks, shared the sobering findings of his department’s city-wide health assessment 2023 Laredo CHNA.pdf. “Thirty-two percent of the respondents reported that they were unable to eat nutritious food due to lack of money,” he noted with concern. But even more worrisome was the diet-related health data. Laredo’s obesity rate was over 45 percent with an official diabetes prevalence of 15.7 percent, figures that are far in excess of both Texas and U.S. averages. Putting a challenge to the 100 or so people gathered at the event, Dr. Chamberlain said, “These numbers are a call to action! We need a collective voice to drive policy decisions.”

Later, I spoke with Councilwoman Cigarroa, who, as a local policy maker, is in a position to address these unfortunate numbers. “I don’t know a family that’s not impacted by diabetes, which is a particularly pernicious disease,” she said, adding that her husband has been practicing cardiology in Laredo for decades and sees lots of heart disease stemming from diet. Of Mexican-American heritage herself, Ciagarroa doesn’t hesitate to blame part of the problem on “traditional Mexican food choices that are [from a health perspective] mostly terrible.” But she also makes it clear that Laredo is medically underserved, and, as the assessment points out, about 30 percent of the residents are uninsured. A large number of undocumented people are also reluctant to seek medical care when they’re sick. “I know too many men who stay at home rather than get help when they have a shooting pain in their shoulder,” she says, “They say it’s nothing to worry about; it’s just indigestion.”

Cigarroa makes it clear that at least another leg of Laredo’s health stool is physical activity. For instance, the heat can be so punishing in the warm weather months that nobody wants to go outside to exert themselves. In driving around Laredo for two days, I also noticed a severe absence of parks. She confirmed my observations, pointing out that the health assessment process heard that problem loud and clear from residents. The study’s methodology included numerous surveys that ranked the community’s concerns, including the finding that, “Over a quarter (26.0%) of community survey respondents indicated that a lack of parks and playgrounds is a problem affecting their health or the health of those with whom they live.”

Binational River Park

A good part of the answer to the lack of safe, multi-use public space may come from the very place that generates much of the region’s tension—the border. At the beginning of 2022, the U.S. and Mexico jointly announced that they intend to create the Binational River Conservation Park that will be a 6.3-mile corridor along the Rio Grande (U.S. name)/Rio Bravo (Mexican name). As a non-walled or fenced 1,000-acre park that incorporates the river, it will join Laredo and Nuevo Laredo. Multiple agencies and government levels are responsible for making this visionary project happen, but U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, Kenneth Salazar (former U.S. Interior Secretary), is receiving much of the applause.

As a project with a $100 million price tag, not only is the Binational River Conservation Park cheaper than Trump’s vanity wall priced at $24 million per mile, it will incorporate over 40 projects such as a monarch butterfly garden since the park is along the monarch’s flyway, a tree farm, a job training site for various outdoor trades, and numerous cultural, educational, and recreational activities. The project “walls” nothing out; it offers a bridge of peace and humanity to all, and in the words of Frank Rotnofsky, co-founder of Able City architects and one of the project’s primary design firms, “This is a once-in-a-lifetime project for planners and architects!”

From Councilwoman Cigarroa’s perspective, the Park builds beautifully on Laredo’s number one natural asset, the Rio Grande. But as one who can barely contain her disdain for Trump and his wall—Cigarroa was the board president of the No Border Wall coalition for several years—she sees any security wall as both an environmental and security failure—it destroys natural wildlife corridors, but also, ironically, fails to keep people out. “Not only does Laredo currently not have a wall, it has the lowest illegal crossing rate anywhere along the border, including places like El Paso that do have walls,” she said. As the elected official who stands as the Park’s staunchest advocate, Cigarroa sees it as “an amazing opportunity” and that “its incumbent upon the city to make it happen.” She speaks to the culturally unifying theme of the park that brings the two cities—Laredo and Nuevo Laredo—together, and also to the larger purpose of creating a “highly visible, safer space in a beautiful setting that will draw people to it for productive activity.” In fact, with more than a little pride in her voice, Councilwoman Cigarroa thinks the Park will one day rival the world-class San Antonio River Walk, as a destination site.

With aspirational language that embraces a new world order, the Park’s website declares that:

The Binational River Park at the Rio Grande-Rio Bravo in Laredo and Nuevo Laredo connects and celebrates our common culture on the United States and Mexico border. It reclaims our shared history, spurs the economy, promotes security on both sides of the river, and restores the ecological treasure we call home. The first of its kind, this international conservation project enhances our quality of life and serves as a prototype for border cities around the world to follow. Two nations, one community. One river. One park.

Farming

While the Park will offer a host of environmental amenities, including ones that will benefit the region’s food system writ large, it doesn’t eliminate the challenges that have left Laredo and its surrounding area virtually bereft of all forms of agriculture. The Food Policy Council and its partner organization, the Laredo Center for Urban Agriculture and Sustainability are attempting to fill that yawning void with smaller-scale farms and gardens. One of the people who is opening a path to a new agricultural future for south Texas is Marcella Juarez, who with her brother Manuel, is converting a mostly fallow 110-acre ranch known as Palo Blanco into an intensive, state-of-the heart, mixed-use food production and instructional farm. On land that has been in her family for 160 years, she hopes to make it a “foundational source of good local food for my community.”

Armed with a master degree in small scale and sustainable farming from Texas State University at San Marcos and a bright and brimming confidence that belies her twenty-something years, Marcella got the farm’s new enterprises up and running at the same time COVID-19 hit. Undeterred and with a business plan that would make your head spin, she started applying hydroponic science and technology, including adapted, solar-powered shipping container farms she designed herself, to the unforgiving, heat-heavy, drought-laden Laredo landscape. Her crops are a daring mix of microgreens, herbs, eggs, and sprouts for a marketplace that is, one might say, only in the tasting stage for such products. But the early reception has been enthusiastic at the farmers’ market, among a few cutting-edge chefs, and with customers for their own farm-to-home delivery service. With the help of the Food Policy Council, Marcella hopes to see market demand grow steadily.

Clearly, Palo Blanco is a mission-driven enterprise. Having attended a small, rural school where her father taught, and where her friends were buying food at a gas station grocery store, Marcella decided at a young age that, “everyone deserves access to fresh food, and that I wanted to use our ranch to feed my friends.” But her views extend beyond a compassion for others and a heart-felt desire to feed her community. “Hispanic people need lots of healing,” she says. “As Mexicans we’re just viewed as farmworkers, not farm owners. God willing, we’ll have more young Hispanic farmers soon.” In addition to wanting to make her community more food secure, she also recognizes its dietary health challenges. “Food is our first medicine,” she said, and in a burst of authentic optimism, she added, “We’re starting to see health, diet, and local food coming together!”

One new development for Texans came to light during the FPC conference that could make a difference to Laredo and young farmers like Marcella all across Texas. The Texas Department of Agriculture (TDA) had completed the “Texas Food Access Study,” Texas Food Desert Study (texastribune.org) which among other things recommended the establishment (passed into law in June) of a state food policy council 88(R) HB 3323 – Enrolled version (texas.gov). Count me as a skeptic when it comes to anything about Texas state government. So, when I heard about this report, I had thought for a moment that Jim Hightower had seized control of the TDA’s commissioner’s office. While some Texas food justice advocates have rightfully criticized the study as not going far enough; in the words of Addie Stone, Policy Specialist at TDA and the study’s co-author, “It’s not perfect, but it’s a start.” I would agree with both the advocates and Stone, but most importantly, it puts the State of Texas on record as acknowledging the state’s high levels of food insecurity and their need to support locally oriented forms of agriculture and food distribution. That gives advocates and local farmers a place to build from.

A little before my ride to the airport arrived, I strolled a short distance down to the banks of the Rio Grande, a river so freighted with history and ecological significance that watching its brown waters gave me momentary shivers. It occurred to me that at least a few H2O molecules now flowing beneath me had started their 1,896 miles journey to the Gulf of Mexico from the snow packs of the Rocky Mountains. There was a majesty of movement before me that existed far beyond my comprehension.

On the Texas bank, a few people baited hooks and lazily cast their fishing lines into the water, making audible plops in the still morning air. Across the river, not much further than I used to be able to throw a baseball, a half dozen Mexicans were also fishing, mirroring their American counterparts who, in all likelihood, were themselves of Mexican ancestry. Just upslope on the Mexican side, hanging languid and limp, was the Mexican flag, so large that it could cover the entire Fenway Park infield. Upriver, a railroad bridge, a symbol of binational commerce, bisected a horizon that was largely dominated by forests and the Rio Grande’s serene, narrowing perspective. It didn’t escape me that this image of peace and beauty softly unwinding before me didn’t allow for the unsavory actions of desperate people who may have been concealed in the bushes and bullrushes. Hurt begets hurt, and when all that you carry on your back are the twin lashes of poverty and violence, fear and flight are your closest companions.

There is an energy in Laredo coming from those associated with the food policy council, city hall, and numerous private sector endeavors that holds the promise of uniting two nations, partnering on shared health and environmental concerns, and equitably distributing a steadily growing prosperity. In all likelihood, success will be determined by whether the Rio Grande is viewed as a mending force and a healing gift of nature, or as a barrier that walls people off from each other and only serves to “give offense.”

June 11, 2023

Part II: Great Falls, Great Food, Great Gaps: The Tale of Paterson and Ridgewood

(This is the second in a two-part series that looks through a food lens at two New Jersey towns—Paterson and Ridgewood—that are only a few miles apart geographically, but light years apart socio-economically. Part I focused primarily on Paterson, while Part II will focus on Ridgewood, my hometown.)

“The province of the poem is the world.” “Paterson” by William Carlos Williams

Former site of the Ridgewood Grocery Coop and the author’s first job.

Ridgewood is a town of 25,000 people located in Bergen County, whose eastern border looks across the Hudson River into northern Manhattan. Based on what I thought I knew about the place where I grew up, the expectations I had for Ridgewood were a redundance of abundance, all the perks that privilege can lay claim to, and a surfeit of greenery and scenery. I wasn’t disappointed. But beneath the enchanting display of its idyllic downtown and serene suburban neighborhoods, Ridgewood’s residents rarely rise to the level of conspicuous consumption, adhering instead to unspoken principles of tastefulness and understatement.

While wandering around Van Neste Square—as pleasing a little town green as you’ll find anywhere—I chatted with two bored police officers propped up against their patrol cars. Joking with them about when they expect the next crime wave to hit, they smirked, then cracked that they had just issued warnings to a couple who were out of compliance with the town’s dress code. With mock indignation, I asked them what they were going to do about the young man asleep on a bench at the far end of the park? “Ah, he’s not hurting anybody,” they replied.

Having just come from Paterson, where only 10 days prior to my arrival eight people were shot in one night (none fatally), I was grateful for the sense of safety the village afforded. But just to confirm I wasn’t missing a carefully concealed cauldron of murder and mayhem, I checked the crime statistics. On average, Ridgewood’s violent crime rate, according to Crimegrade.org, is 0.75 per 1,000 residents earning it an A+ safety rating from this site. Paterson, on the other hand, has 3.73 violent crimes per 1,000 earning “The Silk City” a C- rating.

“War! a poverty of resource. . . “ “Paterson”

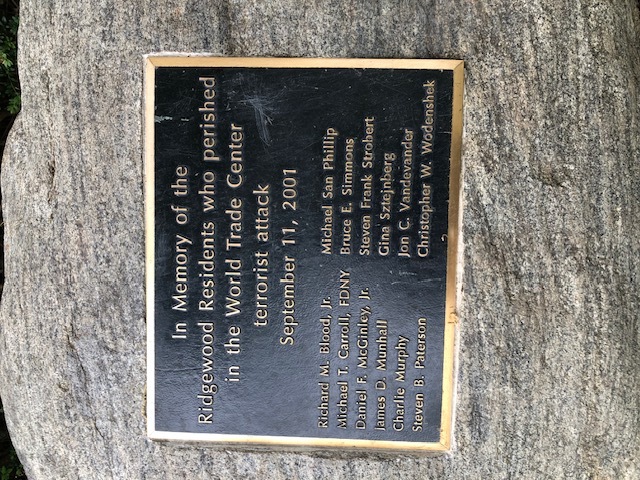

Ridgewood citizens lost in 9/11

Though I paint a picture of a place encased in a bubble, even affluence doesn’t keep you from harm’s way. On the park’s westside is the war memorial that records the sacrifices the townsfolk made to humanity’s bellicosities, including my generation’s big mistake. The Vietnam War took 11 Ridgewood boys, my peers, a loss I’m likely to never forgive this nation’s leaders for. And on an inconspicuous boulder wrapped in shrubbery sits a plaque memorializing 12 Ridgewood citizens whose souls left this earth on 9/11 as the Twin Towers fell to the ground.

But as the person returning to the place that’s largely responsible for who I am, I had to pay my respects to some of the sources of my food stories. Just a hop, skip, and a jump over the railroad tracks from the park is the former site of my first real job—a cooperative supermarket, the last of the pre-granola “old wave” grocery coops that once dominated Main Streets everywhere. Guess what’s there now? A Whole Foods, whose parking lot couldn’t squeeze in another BMW if it had to. As a bag boy for the site’s earlier retail food incarnation, I sent many an egg to an early death by packing the cartons in the bottom of the grocery bag.

Just over half-a-mile from Whole Foods is a Stop & Shop supermarket, where those of more modest means secure their victuals. It was formerly a Grand Union before that chain’s regional identity was forever lost to a wave of corporate raiders who picked over their acquisitions and sold them off for parts. But Ridgewood’s underlying wealth gave this store a second life, albeit under a different name. If you add in a few lesser supermarket retail brands just over the borders of neighboring towns, Ridgewood is a shimmering food oasis when compared to Paterson’s food desert status—officially determined to be the 13th (southside) and 15th (northside) worse food deserts in New Jersey.

I started motoring “uptown,” which is barely a few blocks west of downtown, where I soon passed my former elementary school. What’s notable about my tenure here in the early 1960s was the total absence of a school meal program, perhaps because we all had stay-at-home moms. This forced most students, including myself, to walk home for our so-called lunch period which was an hour in length. A 19-minute walk home, followed by 19-minutes inhaling a Fluffernutter sandwich and a glass of milk, and a 19-minute return walk gave me exactly 3 minutes of playground time before school resumed. Not that anyone was paying attention to empty calories back then, but given that I was walking or biking four miles to and from school each day—morning, noon, and afternoon—I could have been getting a steady IV drip of Fluffernutters with no ill effects.

Formerly The Corner Store and site of the author’s early adolescent candy addiction.

In a similar vein, I had to track down a former den of nutritional iniquity that was only a few blocks from my house. I found my way up North Monroe Street until I took a left onto West Glen Avenue. At that intersection is a small park where my pals and I spent countless hours throwing, hitting, or kicking whatever ball happened to be in season at the time. Our considerable exertions, to say nothing of our astounding acts of athleticism, earned us the right to indulge the treats available at the nearby Corner Store that I was now searching for. Having heard rumors of its demise I was guessing it was gone. To my delight, it was still there—barely signed, no bigger than it was in 1956, and now operating under the name of Park Wood Deli.

I entered the premises with only slightly less reverence than when I once entered Chartres Cathedral. No longer a general grocery store where my mother often sent me at the age of 12 with a one-dollar bill and signed permission note to buy her a pack of Salem cigarettes, it now sparkled with display cases of prepared take-out food. Gushingly, I told the young clerk that this was the place where I came with friends 65 years ago to buy candy, soda, and fruit pies after our ball games. We’d sit outside, against the store’s front wall and consume our “contraband” with gusto. (I can say with a limited degree of certainty that 75 percent of the ultra-processed food I’ve eaten in my lifetime was ingested against that wall). The clerk smiled, and with only a hint of condescension said, “That’s nice to hear, sir; you know what, they still do that,” pointing out the window at the same spot. And wouldn’t you know it, exiting the store just ahead of me, sheepishly clutching similarly illicit items were five boys I guessed to be about 12-years old. Single file, they lined up, backs to the wall, and slid down its smooth surface in unison until they sat on the sidewalk. Devoutly, they unwrapped candy and cakes, and popped their cans of soda.

Noting the irony of how one site of my misspent youth contrasted with my next destination, HealthBarn USA HealthBarn USA | Strong Bodies, Healthy Minds, I headed back up North Monroe for my appointment. This unique, for-profit organization, which provides a range of healthy eating and gardening programs for children and adults, had come to my attention a few months earlier. When I learned that it was located in Ridgewood, my first question was, why? In a place so affluent (the average household income is just shy of $200,000) and highly educated (78 percent of the adults have bachelor’s degrees or better), Ridgewood would be the last place (Paterson being the first) I would choose to place such a beneficial program. Though obesity and diet-related illnesses have cut a deadly swath across all income, race, and ethnic categories, rates are significantly lower for white and college-educated groups. That’s Ridgewood.

Approaching HealthBarn’s location, I drove along streets where the shade trees were so thick and lush you barely noticed the expensive homes the flora carefully concealed. I passed a natural pond with a small, cascading waterfall that ran under the road into a lower pond which turned out to be the southwest corner of Habernickel Park, the site of HealthBarn’s facility.

The public park, formerly a privately owned 10-acre horse farm, is a testament to Ridgewood’s capacity to secure much-needed open space in a town that is 99.9 percent built out. When the owners decided it was time to sell the property, the surrounding homeowners were seized by that paroxysm of fear the wealthy are heir to–a developer will carve out an obscene number of lots for a condominium complex! Quickly, the town, county, and state stepped in to calm jittery nerves by purchasing the land and its house for $7.4 million and turning it into Habernickel Park. When the dust settled in 2016, the modest house, an outbuilding, and an adjoining garden area were leased by Ridgewood to HealthBarn.

“BRIGHTen

The corner

where you are!” “Paterson”

Upon entering the premises, I was greeted by Stacey Antine, HealthBarn’s energetic and entrepreneurial founder. Standing in the foyer, I also found myself engulfed by swirling pools of chattering children who were called either “sprouts” or “seedlings.” I learned that the horticultural designations (later I would also meet “young harvesters” and “master chefs”) were based on the child’s age, which would then channel them into various activities, rooms, and adult leaders. All in all, it was the kind of camper/counselor, controlled chaos atmosphere that I recalled enjoying during my own day camp days.

HealthBarn USA’s children’s garden. Strawberries waiting for some spring warmth.

Amidst the commotion and the occasional wayward seedling uprooted from their pot, I sat down with Stacey to hear her story. Part of her motivation to establish HealthBarn in 2005 came when her father was battling cancer. “But the quote that got me hooked,” she tells me, “was ‘this is the first generation of children who won’t live as long as their parents’ generation based on lifestyle choices.’ When I heard that, I knew I wanted to be part of the solution.” Stacey got out of corporate marketing and started graduate work at NYU to pursue nutrition sciences and become a registered dietitian. Soon, HealthBarn was hatched as a child and family food enrichment program that competes with today’s plethora of non-school activities—athletics, ballet, tuba lessons; in other words, the haute-suburban culture that spawned the term soccer mom.

In addition to hands-on food and gardening programs, HealthBarn offers a summer camp and adult culinary workshops. Between the lovely setting and high-quality programming, HealthBarn attracts people from several nearby towns. As a for-profit business, however, these programs are not inexpensive. One week of HealthBarn’s summer camp is $720, and 10, 90-minute per week summer sessions for young children are $425. Scholarships are available, and Stacey makes a strong effort to raise money to support them, but clearly HealthBarn targets an upscale market.

HealthBarn USA’s business reality prompted Stacey, in part, to establish the non-profit HealthBarn Foundation in 2015 as a way to direct healthy meal services and funding to needy people. The foundation receives donations for the scholarships that underwrite the participation by lower income children in HealthBarn USA’s programs. It also offers a variety of special school nutrition education programs (coincidentally, earlier in the day that I visited HealthBarn, Stacey had provided a nutrition program to a middle school in Paterson).

But the service that really put the foundation on the map is Healing Meals. Described as “a nutritious food gifting program made with love,” it set out to provide special meals to ill children and seniors. As Stacey put it, “I wanted to go beyond just feeding people. I wanted to give people nutritious meals.” By placing quality ingredients and the highest standards of nutrition ahead of quantity and calories, the program developed a favorable reputation throughout Bergen County. In the course of providing meals to seniors, Stacey and her team discovered malnutrition in one of Ridgewood’s affordable senior housing facilities that did not offer an on-site meal service. In cooperation with Ridgewood Social Services, Healing Meals began preparing meals for those seniors who were just barely getting by. This burnished their image further, but more importantly, it prepared HealthBarn for the big bomb that exploded across the U.S. in March 2020.

There is the story of the cholera epidemic and

the well known man who refused to bring his

team into town for fear of infecting them

but stopped beyond the river and carted his

produce in himself by wheelbarrow – to the

old market, in the Dutch style of those days.

“Paterson”

COVID-19 and the lockdown that followed set off a rapid chain of events in the food world. Under the auspices of Ridgewood Social Services, Healing Meals immediately ramped up preparation to 150 meals a day for Ridgewood’s isolated COVID-19 shut-ins. With the HealthBarn programs for children and families shut down, Stacey turned her attention to feeding those in need, a number that was growing by the day, and often under very challenging circumstances. For instance, the staff at Ridgewood’s Valley Hospital was not only struggling to keep up with the surge of patients, but its exhausted staff also needed to be fed. Ridgewood’s then-mayor, Ramon Hache, saw the opportunity to solve two problems at once, the second being the downtown restaurant community that was shut down and laying off large numbers of lower-income workers.

Mayor Hache connected with Paul Vagianos, the proprietor of one of those restaurants, Greek Like Me, and together, under the auspices of the Ridgewood Chamber of Commerce, kicked off Feed the Frontline to mobilize Ridgewood’s restaurants to feed hospital workers. They needed two more things, however: a nonprofit sponsor to receive donations, and the donations themselves. Stacey’s HealthBarn Foundation solved the first problem, and the people of Ridgewood solved the second. In a one-night social event for Ridgewood Newcomers, $13,000 was raised. Over another week or so, an additional $100,000 came rolling in. Everybody was stunned by how fast Feed the Frontline came together. As Stacey told me, “Ridgewood came through like you wouldn’t believe! Pretty soon, we were operating like a well-oiled machine.”

That was only the beginning. Yes, Ridgewood had the resources and the generosity to take care of its own; its downtown restaurant scene was a destination eatery for all of Bergen County, sporting about 50 restaurants throughout the town, 38 of which were highly rated by TripAdvisors.com. But looking beyond the village’s boundaries, COVID was churning up a world of hurt. According to the Bergen County Food Security Task Force, the county had 104,000 food insecure people. How would they be fed when people were losing jobs and the food pantries were shutting down?

Hache, Vagianos, and Antine conspired to take Feed the Frontline to a higher level. Less than two months into the lockdown, the New Jersey Economic Development Authority launched their Sustain and Feed initiative as a way to meet the rising tide of hunger across the state. Stacey, who had not written a lot of government funding applications before, decided to tackle the state application that offered grants ranging in size from $100,000 to $2 million. Being cautious, she thought she’d only aim for $100,000, but then, “I said to myself I don’t think that’s enough, so what the heck, I’ll just add another zero to kick it up to $1 million. I was totally shocked when we got it!”

With a large infusion of state bucks, the Ridgewood Sustain and Feed initiative went into high gear. Vagianos and Hache brought 20 of the town’s struggling restaurants into the fold, and together they started pumping out 1,000 to 2,000 prepared meals a week that were going to needy households identified by local food pantries all across the county. Initially, the state reimbursement rate was $10 per meal, later bumped up to $12, but hardly approaching the kind of revenue that restaurants with $40 menu entrees were used to getting. Nevertheless, it kept them afloat and, perhaps more importantly, it kept their lowest-paid workers employed.

Of course, preparing the meals and identifying the recipients is one thing; delivering them safely to the right place and person is another. That’s where Ridgewood showed its stripes again. Over 400 volunteer drivers emerged from the ranks of town’s citizenry to get the food to where it was needed most. “We never had a vacant volunteer slot,” Stacey told me. “The other counties that received Sustain and Feed grants had a hard time fielding enough volunteers, so they sometimes had to pay Uber and Lyft to make deliveries. Ridgewood is not only generous; it has a great community spirit!”

As we all know, COVID-19 did not go away any time soon. The Ridgewood initiative received two more rounds of state funding totaling $3.5 million. After nearly three full years of operation, the program ended this past March; tens of thousands of the county’s most vulnerable residents received nutritious, high-quality meals prepared by the area’s best restaurants who, in turn, kept hundreds of their staff employed or partially employed.

“The fact of poverty is not a matter of argument.” “Paterson”

When the shit hits the fan, it doesn’t matter whose raincoat you wear. As Stacey sees it, Ridgewood residents have enormous purchasing power and generally don’t get too agitated by such things as food price inflation. “They realize they’re fortunate. They are also very well educated. It’s an incredible equation for success.” That Ridgewood had the wherewithal and the will to serve dozens of county towns besides themselves should be commended and, frankly, made me feel proud that I was one of its native sons.

But wealth has its privileges which beget more privileges, even when it comes to charity. Paterson, with vastly more human need and a paucity of resources, did not, according to Mary Celis, CEO of the United Way of Passaic County, “have the start-up capital and infrastructure that the state required to be eligible for the Sustain and Feed grant program, even though we have greater need in terms of hunger and small businesses on the margin.” Paterson also has a host of other funding priorities, such as crumbling schools, that Ridgewood’s rich tax base makes it nearly immune to.

Ridgewood raised $100,000 virtually overnight and has a concentration of culinary might second to none in the state. Stacey and her partners merely had to tell the community to “Jump!” and they immediately said, “How high?” Emergencies like COVID bring out the best in people, but they also reveal the system’s failures and the yawning socio-economic gaps that cannot be closed by even the most well-intentioned forms of local charity.

Food, and the lack thereof, is the proverbial canary in the coal mine. When people have less purchasing power and restricted access to healthy food, it stretches their resiliency to the breaking point. We shouldn’t have to wait for a crisis to define the gaps between our communities nor test the limits of their residents’ endurance. Local heroes like Stacey Antine, former Mayor Hache, and Paul Vagianos in Ridgewood, and Mary Celis, Mayor Andre Sayegh, and Deacon Willie Davis in Paterson should be celebrated. Like William Carlos Williams’ man who defied the cholera epidemic, they got their wheelbarrows and brought the food to the people.

But are individual heroics and community spirit sufficient to restore equity to and between American communities? Will those courageous, often selfless actions by themselves bring about the conditions that one day put places like Paterson on some kind of par to places like Ridgewood, or will it, despite the best intentions of people of good will, always be its poor stepchild? Clearly, something stronger, something more systemic are needed to rectify the enormous wealth disparities that exist across this nation and are often most visible between neighboring communities.

One thing I think I learned from growing up in Ridgewood is that neighbors don’t let neighbors suffer. To extend that notion beyond the person next door or down the street to nearby, financially struggling communities, I might turn to Alexander Hamilton, whose footprints are all over Paterson and North Jersey, to say nothing of America’s economic system. Hamilton’s greatest contribution to the new republic was the assumption of the states’ debts by the new Federal government. A more comprehensive assumption of the financial need of under-resourced communities by state governments, progressively funded by their affluent residents and communities, is a form of neighborliness that will distribute economic prosperity to all. And with that prosperity will come, among other benefits, the assurance of food security and access to healthy and affordable food for all.

May 29, 2023

Great Falls, Great Food, Great Gaps: The Tale of Paterson and Ridgewood (Part I)

How do I tell an accurate story about places that are embedded in my subjectivity? On the surface it’s a food story because that’s nearly all I know, but it’s also a personal story rooted in the memory of my agitated youth. Decades of experience and reflections have sharpened its edges. Clouds of data have settled like stardust across the plain of my consciousness giving objectivity a stronger foothold. Yet the affluent suburb of Ridgewood, New Jersey, my hometown, and its rough and ready neighboring city, Paterson, occupy a large compartment of my soul where the two places remain divided by a concrete Jersey barrier.

How do I tell an accurate story about places that are embedded in my subjectivity? On the surface it’s a food story because that’s nearly all I know, but it’s also a personal story rooted in the memory of my agitated youth. Decades of experience and reflections have sharpened its edges. Clouds of data have settled like stardust across the plain of my consciousness giving objectivity a stronger foothold. Yet the affluent suburb of Ridgewood, New Jersey, my hometown, and its rough and ready neighboring city, Paterson, occupy a large compartment of my soul where the two places remain divided by a concrete Jersey barrier.

The story begins in the 1950s with two buses—one is brown and the other is yellow. The brown one carried businessmen from Ridgewood to the New York City Port Authority Bus Terminal where they would fan out across midtown to their respective corporate office buildings. The yellow bus transported women from Paterson—about seven miles away—to my town’s tony neighborhoods where they would make their way to the private homes of residents to clean, cook, and care for their children. My house was one of them. The women were known as “cleaning ladies,” they were Black, and my siblings and me called them by their first names even though they were often older than our mother.

Both buses motored up and down Monroe Street, the same route I used to walk or bike to school. Late in the afternoon as I made my way home, the brown bus would sometimes pass the yellow bus as each was returning riders to their respective homes. Occasionally, I noticed the Black women turn their heads to look at the white men whose faces were buried in their evening newspaper. I wondered what these women thought, what Paterson was like, and who, if anyone, cared for them. I knew about the white men. One of them was my father and others were fathers of my friends. The cleaning ladies, who we politely referred to as Negroes, or sometimes “colored,” only traveled 15 minutes by bus, but for a 10-year-old Ridgewood boy, Paterson was as remote and mysterious as Mars.

When you don’t know stuff, you tend to make it up, and what we made up about a place as dark and distant as Paterson was often fueled by racism and white privilege. In that sense, the things you don’t know, or know incorrectly, also become the source of your fear. We saw Paterson as Black, dangerous, and poor. It was the place you did not take your date on Saturday night. It was where Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a contender for the middleweight boxing crown, was falsely accused of murder in 1966, convicted, imprisoned, later spotlighted by Bob Dylan, and not released until 1985. It was the site of civil disturbances in 1968 following Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. It was a place where police corruption and incompetence exceeded even New Jersey’s legendary standards of skullduggery. (And it is, unfortunately, still such a place: the New Jersey attorney general took control of the Paterson police department this March, due to its inability to manage itself, including police killings of Black men).

In an effort to gain some clarity over these dissembling memories, I embarked on a modest pilgrimage to Ridgewood and Paterson to look at each place afresh, and as I am wont to do, I did it through a food lens. Food gives me a place to pivot from, a solid and necessary footing from where I can interpret a city’s broader social and economic dimensions, perhaps ones that would afford me more accurate views into my discontent. But the food lens was not just a vocational choice, it was also because the region’s poetic godfather, William Carlos Williams and his epic 20th century poem “Paterson” admonished, “Say it! No ideas but in things.” To capture the truth, in other words, I had to let my ideas grow out of the reality and immediacy of people, their deeds, and nature. Those are the things that matter, and I can think of no better thing than food.

To begin, a community’s food system has much to do with its social and economic conditions, and since numbers are also things, or at least representative of other things, here’s an abbreviated side-by-side comparison of Ridgewood and Paterson (all figures are for 2021).

RidgewoodPatersonPopulation 26,202157,794Median Household Income ($)194,256 48,450Persons without health ins. (%) 2.9 20.9Average life expectancy (years) 86 74Poverty rate (%) 2.6 25.1Bachelor’s degree or higher (%) 78.3 12.5Black or African American (%) 1.2 24.7Hispanic or Latino (%) 8.7 62.6These are the things that tell a tale of two cities. Ridgewood and Paterson are geographically close, but the socioeconomic differences are achingly far apart. To place Paterson in a larger metro New York context, Mary Celis, president and CEO of the Passaic County United Way put it this way, “Paterson is only nineteen miles from Wall Street.”

Imbalances like these translate into long-term consequences for children. Take education, for instance. Despite hundreds of millions of dollars of investment by New Jersey over the past two decades, Paterson Public Schools—which educate nearly 25,000 students in more than 40 school buildings, 17 of which are over 100 years old—remain in desperate need of new facilities and extensive repairs (northjersey.com). Without the tax-base to adequately support its physical infrastructure, to say nothing of ongoing operations, the Paterson school system must rely on mostly inadequate aid from the State of New Jersey whose often unsympathetic suburban state legislators look askance at urban needs.

…poor, the invisible, thrashing, breeding, debased city

“Paterson” by William Carlos Williams

Never could such conditions be imagined for Ridgewood schools. My parents deliberately moved there in the early 1950s because even then the schools had a reputation for being among the finest in the state. Later, new residents would mortgage themselves to the hilt for the privilege of settling themselves anywhere within the village’s boundaries so that their little Marks and Susies could one day claim a diploma from Ridgewood High School. Of course, the property taxes required to maintain an exceptional educational standard would suck the marrow from your bones. A classmate of mine and former mayor of Ridgewood is reputed to have said that residents will never flinch from raising taxes in order to support the schools—that, effectively, the sky’s the limit. So steep is the “membership dues” that, as the tale goes, the lawn signs congratulating Mark and Susie for graduating from Ridgewood High in June are soon replaced by for-sale signs in July.

Paterson lies in the valley under the Passaic Falls

Its spent water forming the outline of his back…

[T]he river comes pouring in above the city

And crashes from the edge of the gorge

In a recoil of spray and rainbow mists…

“Paterson”

Given that Paterson was envisioned by Alexander Hamilton in 1792 as America’s first industrial center, there is more than a little irony in the city’s struggling financial condition today. Building off the Passaic River and its Great Falls potential for energy generation, a system of channels was constructed to power textile mills and later the manufacturing of locomotives and airplane engines. Hamilton led the founding of the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.), New Jersey’s first corporation, to oversee what became a juggernaut of creation, technology, and industrial output.

When the demand for all that productive might declined after World War II, so did the surrounding economy. Today, the Great Falls, a still functioning hydroelectric plant, and the Paterson Museum are joined loosely around the Paterson Great Falls National Historical Park which is now part of the National Park System. Nearby, you will find recently revitalized Hinchliffe Field, one of only two remaining Negro League baseball stadiums in the country. It stands as a testament to the national shame of segregation and the resilience of Black athletes. The reactivated stadium is also accompanied by the construction of 75 units of affordable senior housing, both projects instigated by Paterson’s Mayor Andre Sayegh.

As with similar efforts I’ve seen in other cities where a well-intentioned economic comeback is underway, the focus is often on burnishing one gem while ignoring the setting. The Falls and the adjoining viewing areas created by the Park Service are one of the more spectacular natural sites in the mid-Atlantic region. And if you take the time to absorb the totality of U.S. history compressed into this one small area, most people would not fail to be impressed. Unfortunately, the surrounding neighborhoods are in disrepair and probably on some city list for renovation. The signage, roadways, and parking in and around the historic site will leave the visitor hopelessly bewildered (I swear, Siri told me, “Sorry pal, I’m lost. You’re on your own!”). The general maintenance and appearance of the area are such that you could imagine the Paterson Sanitation Department, some private museum board of directors, and the Park Service arguing over whose job it is to pick up the trash, fix the broken fences, or provide a minimum of landscape services. On the day I visited, the main roadway into the historic area was closed while emergency construction crews repaired an aging street that appeared to retain vestiges of Hamilton’s wagon ruts.

In spite of all this, it’s worth a visit!

Against this backdrop, it’s not surprising that food has become both an opportunity and a challenge. Andre Sayegh—the city’s youthful and visionary second term mayor—is using food as a part of the city’s comeback plan. I was admittedly delighted to see Paterson’s home page tagline read “Great Falls, Great Food, Great Future!” No argument from me about the Falls; the city’s multi-ethnic restaurant scene (there are 72 nationalities represented among city residents) may one day put Paterson on some kind of regional food map; as to the future, well, time will tell.

Consistent with his aspirations, the mayor, a lifelong resident of Paterson with a Jimmie Fallon-like personality, did a video of a five-restaurant food crawl with northjersey.com’s food editor, Esther Davidowitz (Palestinian restaurants in Paterson: Our food crawl to 5 in 5 blocks (northjersey.com). Together, they noshed their way down Palestinian Way, an honorary street name selected to recognize the city’s Palestinian population, the second largest in the U.S. To call the blocks along Palestinian Way a food Mecca is more than an obvious pun—the large number of halal food outlets and mosques speak to the depth and diversity of Paterson’s Arab community—it is also a rich and rewarding cultural immersion.

Having had lunch at Al-Basha, one of the restaurants on their crawl, I can attest to how delicious the cuisine is. In their video, Sayegh and Davidowitz sampled hummus, compared the restaurants various baba ganoush dishes, waxed enthusiastic over an okra and meat creation served over rice, and had a cute argument about the correct shape of falafels. What stood out for me about the piece were two things: that a city mayor would celebrate his community’s cuisine with so much articulate gusto, and that one of the region’s major media outlets would raise up restaurants in a tattered city that would not be a dining-out destination by its generally prosperous viewers (the broadcast’s opening line captured that ambivalence: “Been to Paterson lately? Ever?”). In a not-unrelated note, Mayor Sayegh also understands the connection between calories in and calories out. One of his quality-of-life initiatives is to have active outdoor recreation space no more than a half-mile from any residential dwelling—no small task in a city as densely built as Paterson.

But the big food challenge is not where to eat out, it’s food insecurity—affordability, access, and dietary health. Paterson has a large low-income population, virtually nothing of economic substance to anchor its tax base, and not enough financial fuel to rev up its economic growth engines. Capturing as much economic benefit from food—normal household consumption, restaurants, and various food chain activities—is an obvious default position for a resource-poor place. But until the time when a rising economy can lift all ships, people must be fed, and to do that well in Paterson requires a steep climb up a mountain of food injustices.

In 2021, the New Jersey Department of Economic Development conducted a statewide food desert and access study. Using the USDA standard definitions, the study identified 50 areas around the state—urban, suburban, and rural—as food deserts and then ranked them as to their comparative “desertification.” Paterson’s southside was the number 13th worse while its northside came in number 15 Food-Desert-Communities-Designation-Final-2-9-22.pdf (njeda.gov).

The ironic accompaniment to a food desert is a food swamp—an oversaturation of fast-food places and low-nutritious food outlets of which Paterson is awash. Filling in the food landscape, and in response to high levels of food insecurity, Paterson is also home to five large food pantries, each receiving over $500,000 a year through Emergency and Shelter funding, according to Mary Celis of United Way of Passaic County, which sponsors the Passaic County Food Policy Council Passaic County Food Policy Council | United Way of Passaic County (unitedwaypassaic.org).

Food studies like New Jersey’s and the tabulations of a city’s other food outlets can tell you a lot about a food environment, but they don’t reflect how people living in those places cope with a multitude of realities that an anti-poor marketplace imposes on them. To get a better sense of that, I had lunch with Mary and six of her Food Policy Council members at Al-Basha’s.

Clearly, themes of underinvestment/disinvestment and their impacts on Paterson’s food system were strongly shared by everyone. “Good food is not available in Paterson,” was the conclusion reached by Deacon Willie Davis, one of the city’s leading urban agriculturalists. This was echoed by others including Kimmeshia Rogers-Jones, a social worker and long-time community activist who sees the small grocery stores that remain in the city and those just beyond its borders as predators who take advantage of Paterson’s BIPOC community. “They know we’re coming because we have no choice, which is why they have low-quality food. Go to a Shop-Rite [a regional supermarket chain] in Fair Lawn, Wayne, or Paramus [higher income, nearby towns] and the quality is much more improved.” She also expressed her frustration with local food insecurity: “It’s mind-boggling to be in a rich country when we have so many hungry people in Paterson.”

Shana Manradge, a food entrepreneur and founder of A Better Market, said, “We [BIPOC residents] go to places where bad food is because ‘they’ know we’ll buy it! What’s affordable to us is not healthy and causes diseases—that’s the inequity!” The relation between the low quality of available and affordable food, and what’s healthy was underscored by Darryl Jackson, a teacher and political activist. A number of years ago, Darryl adopted veganism as his primary diet in reaction to the unhealthy food that filled his neighborhood. “I realized how addicted I had become to the sugars and salt around me. I realized how my body was affected by the food available in my community.” While he likes to make it clear he’s “not militant” about his choice to be vegan—“I’ll eat whatever in the company of others”—he feels passionately that there’s a strong relationship between Paterson’s low-quality food, the residents’ health, and their low levels of activism. “Not enough people act against these injustices because their food undermines their vitality [including] not knowing how to grow their food.”

The more macro aggressions of society’s injustices were also highlighted. Steve Kehayes from Habitat for Humanity reiterated that “access to safe and affordable food and housing are human rights,” ones that the group felt were not fulfilled in Paterson. Lisa Martin from City Green, a statewide gardening organization, pointed out that there’s a need for a living wage to be paid to everyone. As the leader of the Passaic County United Way, Mary Celis confronts the depth and breadth of the region’s inequalities and their consequences every day. She bemoaned the absence of fair tax policies that would progressively tax and equitably distribute wealth and income. “The nation’s COVID allotments and waivers ended which reduced the expanded Child Tax Credit and SNAP benefits and is impacting access to Medicaid. These policy changes are having adverse effects on people in Passaic County, and they are issues that the Food Policy Council cares dearly about,” she said.

Beauty is a defiance of authority. “Paterson”