David Boyle's Blog, page 39

March 10, 2015

The Liberal business paradox and why it is so infuriating

Wander through the nineteenth century and what you find, over and over again, is an alliance between business and Liberalism. Not so much with the Whig landowners but with the radicals and non-conformists.

Because, as I argued in my recent pamphlet with Joe Zammit-Lucia, it was a different understanding of business and its potential – based on the right of the small, weak and new to challenge the big, strong and feather-bedded with economic privilege.

What’s more, the two key Lib Dem ministers in this area have re-invented the old radical tradition with a range of important measures from clamping down on unfair competition from tax avoiders (Danny Alexander) to turbo-charging apprenticeships (Vince Cable).

But then there is the paradox. Because most modern Lib Dems have a breathtaking blindness when it comes to economics of all kinds. It isn’t that they don’t think it’s important – just that it doesn’t interest them. At all.

But worse, once the party marketing or campaigning staff get hold of it, Lib Dem economic policy takes on a smug embrace of the status quo. It reeks of self-satisfaction. It loses any sense of a radical challenge.

Why is this? I would love to know. Is it because the copywriters are just going through the motions because it is about money? Is it because they hand over to smuggest business lobbyists because they are prepared to write it?

How else are we to understand the party’s briefing on business yesterday?

It isn’t that it is wrong. It just misses the point. It is also headed by a grandiose and vacuous statement of ambition - why would we want to be the biggest economy in Europe if it isn't spreading prosperity? Who wants to be the biggest economy if it is all earned by billionaires in London?

But the real gap is in the ‘finance for growth’ section. Vince Cable’s British Business Bank is an important achievement, but it isn’t a solution to the glaring problem faced by the UK economy - which is that small business lending is still falling.

Why? Not because of a lack of capital - the BBB looks after that - but because there is no effective lending infrastructure and even the British Business Bank needs that to work, because it doesn't have its own. The big banks are no longer able to lend to SMEs, the drivers of the economy, because they lack the local infrastructure, and their risk software at regional office is wholly inadequate.

So what are we going to do about it? Pretend it isn't a problem for fear of upsetting the banks (they don't like this kind of talk)? Or doing what Lib Dem party policy now recommends:

A new, diverse local banking system, including community banks and community development finance institutions (CDFIs), funded by the big banks - which will pay for the infrastructure to lend in places and sectors where they are unable to lend themselves, using their geographical lending data to calculate how much they pay each year.

I know Danny Alexander and Vince Cable are aware of this. But when their pronouncements get mediated by the party marketeers, it turns into vacuous mush. What is the point in making these pronouncements if they neither identify the problem nor look forward to a solution which hasn't already been enacted?

A far better purpose for the Lib Dems, to demonstrate their clarity of thought and boldness in business, is to put enterprise - and small business especially - at the heart of every area of government.

You want to know how to do that? Well, you start by building the kind of lending and investment infrastructure that might have some chance of making it possible.

The UK is blessed by having the leading financial sector in the world in the City of London. The problem is that it has no skills, no track record and no expertise in the one thing the UK really needs - turbo-charging the SME sector.

Would Lib Dems in government tackle this problem? Because if they would, maybe it might be an idea to say so.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Because, as I argued in my recent pamphlet with Joe Zammit-Lucia, it was a different understanding of business and its potential – based on the right of the small, weak and new to challenge the big, strong and feather-bedded with economic privilege.

What’s more, the two key Lib Dem ministers in this area have re-invented the old radical tradition with a range of important measures from clamping down on unfair competition from tax avoiders (Danny Alexander) to turbo-charging apprenticeships (Vince Cable).

But then there is the paradox. Because most modern Lib Dems have a breathtaking blindness when it comes to economics of all kinds. It isn’t that they don’t think it’s important – just that it doesn’t interest them. At all.

But worse, once the party marketing or campaigning staff get hold of it, Lib Dem economic policy takes on a smug embrace of the status quo. It reeks of self-satisfaction. It loses any sense of a radical challenge.

Why is this? I would love to know. Is it because the copywriters are just going through the motions because it is about money? Is it because they hand over to smuggest business lobbyists because they are prepared to write it?

How else are we to understand the party’s briefing on business yesterday?

It isn’t that it is wrong. It just misses the point. It is also headed by a grandiose and vacuous statement of ambition - why would we want to be the biggest economy in Europe if it isn't spreading prosperity? Who wants to be the biggest economy if it is all earned by billionaires in London?

But the real gap is in the ‘finance for growth’ section. Vince Cable’s British Business Bank is an important achievement, but it isn’t a solution to the glaring problem faced by the UK economy - which is that small business lending is still falling.

Why? Not because of a lack of capital - the BBB looks after that - but because there is no effective lending infrastructure and even the British Business Bank needs that to work, because it doesn't have its own. The big banks are no longer able to lend to SMEs, the drivers of the economy, because they lack the local infrastructure, and their risk software at regional office is wholly inadequate.

So what are we going to do about it? Pretend it isn't a problem for fear of upsetting the banks (they don't like this kind of talk)? Or doing what Lib Dem party policy now recommends:

A new, diverse local banking system, including community banks and community development finance institutions (CDFIs), funded by the big banks - which will pay for the infrastructure to lend in places and sectors where they are unable to lend themselves, using their geographical lending data to calculate how much they pay each year.

I know Danny Alexander and Vince Cable are aware of this. But when their pronouncements get mediated by the party marketeers, it turns into vacuous mush. What is the point in making these pronouncements if they neither identify the problem nor look forward to a solution which hasn't already been enacted?

A far better purpose for the Lib Dems, to demonstrate their clarity of thought and boldness in business, is to put enterprise - and small business especially - at the heart of every area of government.

You want to know how to do that? Well, you start by building the kind of lending and investment infrastructure that might have some chance of making it possible.

The UK is blessed by having the leading financial sector in the world in the City of London. The problem is that it has no skills, no track record and no expertise in the one thing the UK really needs - turbo-charging the SME sector.

Would Lib Dems in government tackle this problem? Because if they would, maybe it might be an idea to say so.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 10, 2015 04:15

March 9, 2015

Is Russell Brand to blame for climate change?

The climate march went ahead. The Guardian devoted their whole front cover to the issue. Russell Brand spake from the platform. But you have to ask yourself – given the stakes – why the climate change campaign seems so Sisyphean (I don't know if there is such a word: I mean like pushing stones uphill).

The climate march went ahead. The Guardian devoted their whole front cover to the issue. Russell Brand spake from the platform. But you have to ask yourself – given the stakes – why the climate change campaign seems so Sisyphean (I don't know if there is such a word: I mean like pushing stones uphill).It shouldn't be so difficult, after all. Why wouldn't people subscribe to the idea of rescuing human life on earth? Or saving themselves ruinous costs? And yet they resist it very effectively, with increasing tenacity.

And here, as so often, Jonathan Freedland hit the nail squarely on the head.. Look at the speakers at the climate march on Saturday: Russell Brand and the usual, predictable suspects.

The answer he suggests is that it is because the climate campaigners have explicitly limited themselves to a campaign from the left. They have embraced the vocabulary and symbolism of the left. No campaign so fundamental, asking such fundamental changes of people and government, is going to succeed unless it can also attract the right.

As Jonathan says, the first speech on the subject was made by Margaret Thatcher as prime minister. It shouldn’t be impossible to imagine a conservative climate campaign in parallel and integrated to what we have now.

The Green Party is booming at the moment, but I can't help feeling they are making a similar mistake, They have embraced the language of the left, presumably to pick up disaffected Lib Dem and Labour votes – which would have come to them anyway – but, by doing so, have put a glass ceiling in the way of their growth as a movement.

These issues are too fundamental to campaign from one side of the political divide alone. By doing so, we render our campaign ineffective - and we don't have that luxury.

This is not intended as a criticism of the left, or of the right come to that, but to say something about how causes as urgent as the climate campaign achieve their objectives. It is by building alliances, not by focusing the appeal.

But there is another problem which Jonathan Freedland never mentions. By couching the climate campaign purely in terms of the left, it has become associated with the same problem that has beset the left over the past generation – it becomes defensive, melancholic, backward-looking and nostalgic for the past. It becomes irritatingly puritanical and disapproving.

That has been the left's besetting sin since they were swept aside in the 1980s, and it is one reason they have failed to claw back a coherent, mainstream political solution.

If the climate campaign is going to succeed, as my friend Joe Zammit-Lucia keeps arguing, it will need to persuade people – not so much that the earth is doomed – but that their lives can be better, richer, wealthier and more fulfilled by embracing the radical changes that are necessary.

The campaign needs to demonstrate that renewable energy is the key to independence and prosperity. It needs to paint a picture that solves problems rather than tiptoeing away from them back into a an embittered identification of those to blame.

What I find so frustrating is the incredulity that climate change campaigners (like me) feel that their message is so difficult to put across – the demonisation of the other side – when the tools for winning are within their grasp.

Why don't they grasp them? Because they have to win on their own terms? That they have to win by being melancholic or spreading blame? Because to win in other ways looks like cheating? Or, worse, it sounds conservative?

Yet the longer it takes to make this shift, the more difficult it will be to get people who are shiftable out of their entrenched positions. In fact, they are risking failure on this vital issue by their failing to break out of the conventional political divide - as if, to do so, would commit a greater sin than losing the whole world to global warming.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 09, 2015 04:23

March 5, 2015

Not small enough? Just how inefficient our economy is

I’ve been interviewing economists and radicals for the last six months about the conundrum of local economics, and why they don’t see eye to eye on it – given that they want the same thing (more prosperity).

The result has been my co-written book People Powered Prosperity.

One of the things I realised while I researched it is that, actually, the word ‘local’ is neither very accurate nor very useful.

It is inaccurate because the real problem isn’t so much the lack of local financial and enterprise institutions (though that is a problem too), but how to scale them up without losing the access to local information and relationships which makes them so effective.

The answer is to network them together to a new mezzo level, between local and national, but making sure that their control remains local.

It is misleading because the word ‘local’ screams to conventional economists the implication ‘protectionism’. It appears to be about borders. They worry about wholly irrelevant issues – the kind that obsess the official mind – like defining ‘local’.

No, the kind of ultra-local economic revitalisation I’m interested is designed to encourage more competition, not less. More choice, not less. It is about small-scale before it is about local.

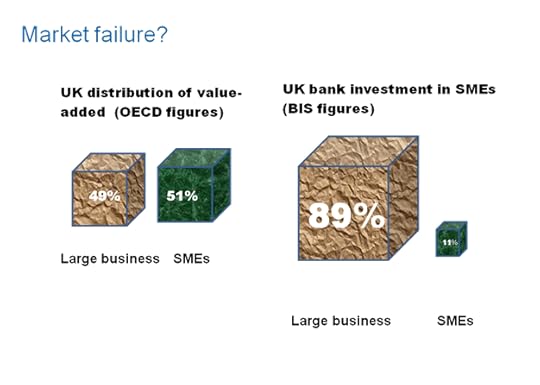

One of the interviews I carried out was with the American pioneer of local economics Michael Shuman, and it was he who encouraged me to make the extent of the market failure visible – because it is precisely that that big banks and mainstream policy-makers deny.

He suggested I look up the comparative value-added figures for the UK for big business and SMEs.

Sure enough, the OECD tables are pretty clear. SMEs earn 51 per cent of the profit in the UK. A properly functioning economy would therefore be funnelling about half the investment in their direction.

In fact, only 11 per cent of big bank investment is going to SMEs according to BIS.

You might reasonably answer that small businesses don’t need the same kind of investment. This is true, but they do need something – even if it is just mentoring – which the mainstream financial world manifestly assumes it will somehow provide for itself.

Look at national resources and see where they are concentrated. We continue to rely on half the value in the economy coming from small business, but do nothing about it.

There is the extent of the market failure that the current system is so blind to.

The solution? Provide the UK with the kind of local financial institutions most other nations have. Don’t take the enterprising innovators for granted.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 05, 2015 02:51

March 4, 2015

Revitalising cities means escaping from acronym hell

I am now in my fifties - a bit of a shock and I still haven't got over it yet - and I have discovered over the past few years that one political objective above all others has gripped me.

I am now in my fifties - a bit of a shock and I still haven't got over it yet - and I have discovered over the past few years that one political objective above all others has gripped me.I'm not saying it's the only thing that matters - just that it is what I want to do now. I want to find ways that the mainstream and the radical thinkers and practitioners can learn from each other.

There is nothing so frustrating in UK public life - and in economics particularly - that decades go by in mutual incomprehension before new ideas can be dragged kicking and screaming into mainstream policy. I am tempted to say, only when they are worn out.

So the seminar I organised at the Treasury yesterday, to discuss the findings of my book People Powered Prosperity , was a step along that long and rather frustrating road. It was chaired by the Chief Secretary to the Treasury - and Danny Alexander has a creative and heroic ability to ask the mainstream difficult questions and to keep on asking them.

It also managed to get in the room, not just the civil servants running the cities and local growths team, but a representative bunch of the local bankers, local energy pioneers, local procurement advocates, local currency thinkers who are pushing forward the boundaries of what might be possible.

So far so good, but I realised by the end that the task has only just begun. It was inspiring to hear people like Ben Lucas of the Cities Growth Commission and Edward Twiddy of the new Atombank - and former Newcastle leader John Shipley - using language which straddled the two worlds.

There is a new understanding emerging, it seems to me, that the levers for revitalising local economies will be local - and that we have suffered from the illusion that national institutions can ever be effective at a job that requires specialist local knowledge.

The next stage is, I think, to form some kind of semi-official local economics sounding board inside the Treasury and Cabinet Office so that the new ideas and techniques can permeate quickly.

That's what I want to do next.

But I was reminded of the huge gap that still remains. At the end of the seminar, I talked to one of the most effective of the radicals, from the Transition Towns movement, and asked her why she had been so quiet.

"Because I was so horrified," she said.

I could see immediately what she meant. One of the problems about getting economic policy-makers in a room together is that you sink immediately into acronym hell.

And the acronyms do tend to get in the way of the core reality - which, as she reminded me, is this.

There is a huge energy in the poorest places which remains untapped, untouched by financial or business institutions. It is an entrepreneurial energy which is the future driver of change and innovation - if we can find institutions of the right shape and responsiveness to shape it into real wealth.

That is the extent of the failure in the past and the extent of the hope. If we can do it. But we tend to sink back into acronym hell all too easily and forget it.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 04, 2015 02:08

March 3, 2015

Jerusalem and the West Lothian anthem question

I see that Laura Wright, the soprano who plays rugby for Rosslyn Park and also the singer of the official rugby anthem, has urged whoever takes these decisions to use Jerusalem as the anthem for England in this year’s rugby World Cup (for some reason the Standard story yesterday is not online).

I see that Laura Wright, the soprano who plays rugby for Rosslyn Park and also the singer of the official rugby anthem, has urged whoever takes these decisions to use Jerusalem as the anthem for England in this year’s rugby World Cup (for some reason the Standard story yesterday is not online).She says the English need something to compete with Flower of Scotland and Land of My Fathers for inspiration. That isn’t to say that God Save the Queen isn’t inspiring. The point is – and Laura wasn’t so political – is that it is the anthem of the nation as a whole. It seems tactless, to say the least, to use it to inspire the English team when it is playing Scotland or Wales.

It is the cultural equivalent of the West Lothian Question and it won’t go away.

Personally, I think this is inevitable eventually. I’m sorry that, as usual, sheer conservatism is preventing some kind of decision.

I also think Jerusalem is the perfect anthem for the English nation because of its complex spiritual message – not just from Blake, but all those other people involved in its development from the poet Robert Bridges and the composer Hubert Parry to the great explorer and campaigner Francis Younghusband.

It seems to me that a really effective, inspiring anthem must point beyond either bombast or banality, to something with depth and authenticity - and something way beyond the everyday. Jerusalem does that.

You can read the whole strange story of the words and music in my ebook Jerusalem: England’s National Anthem .

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 03, 2015 13:57

March 2, 2015

Miliband's unexpcted favour to the Lib Dems

The personal finance expert Martin Lewis has come out against Labour's plan to cut student fees to £6,000 a year. He says it is is subsidy to future bankers, as he explains:

The personal finance expert Martin Lewis has come out against Labour's plan to cut student fees to £6,000 a year. He says it is is subsidy to future bankers, as he explains:"The only people who would gain from it are those who would clear their entire loan for tuition fees plus any loans for living costs, plus the interest, within the 30 years. To do this you’d need to be a high earner.

"To see the exact amount, go to my student finance calculator and play about with different scenarios – watching the impact of reducing tuition fees. It shows that only those with a STARTING SALARY of at least £35,000 – and then rising by above inflation each year after – would pay less if you cut tuition fees (we have assumed the student also takes out £5,555 in maintenance loans per year).

"That’s a very high amount, mainly only City law firms, accountancy firms and investment banks pay that much as starting salaries. Is that really who Labour wants to target with this plan? Worse still, by cutting tuition fees it will reduce the bursaries that universities can give to attract poor students."

He is quite right about this. It also shifts resources from existing students to future, well-paid graduates.

Because the truth about the - originally controversial - new system of university finance and students loans, that Vince Cable brought in, is that it bears few similarities to Labour's student loan system that it replaced. It is only paid off when graduates can afford it, and those thresholds are very much higher now than they were. It safeguards the low-paid theology graduates (I speak as one), but still provides them with the resources to study.

It provides proper funding for universities and it has underpinned a new life for universities, where a higher number of poorer students have been applying to go to university than ever before.

In fact, if Vince Cable had been a trickier customer - or longer in the job - he might have reasonably been able to claim that he had in fact abolished the old student loan system, as promised, and brought in a graduate tax with major safeguards for people who don't earn higher salaries.

Cable was too honest for that kind of Blairite spin. But there is still a powerful case to be made for the new system, which is very much better and more generous than the old system.

In fact, it seems to me that Ed Miliband has done the Lib Dems an unexpected favour. If he had not come up with this proposal, then the Lib Dems would have tiptoed through the general election whenever student loans were mentioned. They would have been constantly on the back foot.

Now they are being forced to defend the current system, and therefore defend their record. Since the current system is so much fairer than the old one, and they have a good case - this seems to me to be a heaven-sent opportunity.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 02, 2015 00:50

February 26, 2015

Making the opposite mistake to Natalie Bennett

I've just been listening to Natalie Bennett's car crash interview and rather wish I hadn't. It reminded me uncomfortably of some of the radio interviews I've done myself over the years. I don't think very well on my feet - one of the reasons I write this blog instead of talking too much. I write too much instead.

I've just been listening to Natalie Bennett's car crash interview and rather wish I hadn't. It reminded me uncomfortably of some of the radio interviews I've done myself over the years. I don't think very well on my feet - one of the reasons I write this blog instead of talking too much. I write too much instead.But I've been wondering afterwards what her mistake was, precisely. As leader of a party with one MP, she doesn't need to use the meaningless language of Westminster discourse. There was no need to put a figure on the number of homes they would build.

The spurious number of 500,000 new homes was mentioned, and it is worth saying that - even during the Macmillan and Wilson years of jerry-built high rise flats, the UK never managed more than 400,000 a year.

Conventional political wisdom says that you have to express these things in terms of numbers and costs or nobody believes you, but is that really the case? The figure of 500,000 a year is too round a number to be believable, too imprecise to be serious. And either the basic policy work had not been done, or Natalie Bennett had forgotten the details.

I was irresistably reminded of the fatal moment when Charles Kennedy revealed a less than complete mastery of the details of the Lib Dem proposals for a local income tax during the 2005 general election. His wife had just given birth, so perhaps it was understandable - but it was a critical moment too. I expect this will be a critical one for the Greens.

But before Lib Dems get too holier-than-thou about it, it is worth remembering that they are making precisely the opposite mistake to the Greens.

The Greens have not worked through the practicalities of their proposals in sufficient detail. They are not focused enough on immediate policy, but they have sharpened their ideology and everyone knows what they are for.

The Lib Dems are hugely exercised with the short-term strategies of getting policy details through Whitehall and the coalition. Their whole attention is on making things happen, but have forgotten - hopefully temporarily - that they exist for a purpose beyond the moderation of Conservative and Labour excess.

If they forget sometimes what they are actually crusading for - the fundamental purpose of the party and its ideology - the Greens never do. So don't let's be smug about Natalie Bennett's embarrassment. She is at least beginning to think about the practicalities of radical policy-making.

I want the Lib Dems to do well this year as much, if not more, than anybody. Nobody could accuse them of stinting on the policy front. There will be powerful green policies in the Lib Dem manifesto. But the more I can persuade the party to provide that crusading edge - to remember what their long-term purpose is - the more I can improve their chances.

Starting perhaps with recommending my own attempt at radical practicalities in my new book (written with Tony Greenham) on the practicalities of ultra-local economic regeneration.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on February 26, 2015 02:33

February 25, 2015

Military weakness is not as dangerous as military delusion

I joined the Liberal Party in 1979, as a student journalist, having interviewed all the local parliamentary candidates. Dermot Roaf, then the Liberal candidate for Oxford City, spent well over an hour with me in the middle of the day, when he must have had more urgent people to deal with – and, by the end, I was convinced. I went off then and there and paid my subscription.

I joined the Liberal Party in 1979, as a student journalist, having interviewed all the local parliamentary candidates. Dermot Roaf, then the Liberal candidate for Oxford City, spent well over an hour with me in the middle of the day, when he must have had more urgent people to deal with – and, by the end, I was convinced. I went off then and there and paid my subscription.But one of the reasons why I embraced the cause so enthusiastically – rather too enthusiastically for my own good – was my growing sense of irritation at the political discourse.

Why was it that the people who had particular ideologies bred into them seemed to cling to these bundles of ideas, some of which seemed contradictory – apparently because they were psychologically pre-disposed to do so?

Why was it, for example, that Conservatives tended to oppose public spending – but not, apparently, when it came to defence? Why was it that Labour supporters seemed to back all kinds of extra spending – but not, again apparently, when it came to defence?

It was all very odd, and I wondered this morning when I heard the news about sending troops to the Ukraine – can Cameron do that without a vote in the Commons? – whether the same contradictions applied.

I am clearly different these days. I recognise a tyrant when I see one, and Putin is one. There are clearly risks to the Baltic states, and it would be a setback for civilisation if they fell back under Russian control. Perhaps as much as Nazi control was of Poland.

What I do find indefensible is the way that successive governments, but the Blair government in particular, approached these issues with their preference for symbolic gestures to real action. It meant that, briefly at least, they could cut defence spending and still invade Afghanistan. And Iraq.

In the long run, it meant the humiliation of UK forces, and the undermining of our reputation for military competence – because our forces were not equipped or trained or prepared or numerous enough for the role they were supposed to be playing.

Is this what Cameron is doing? Sending 75 troops to Ukraine because it is a cheap gesture? Or is it the same kind of gesture as the one that Spanish government used during the first Gulf War: they would send forces to support the coalition, but on condition that they would leave if there was any fighting?

Because this kind of symbolism is far more dangerous that doing nothing. Sabre rattling might have its place, but if you sabre rattle when you have long since sold off your sabre, then you can get into difficulties – which the rest of us will have to pay for.

Am I advocating strong defence? Not necessarily. But the current mismatch between political rhetoric and military swagger, and the actual military resources we have at our disposal, is so stark that it is downright dishonest.

Something has to give. We are heading next month to the centenary of the Dardanelles expedition (March 18: the first attempt to force the narrows by sea), and it is a good moment to remember the psychology of military incompetence.

The commanders in 1915 deluded themselves about the enemy they faced, putting out reassuring orders to the officers explaining that Turkish troops were afraid of the dark. The result was inevitable.

It isn’t necessarily weakness that precedes military disasters. It is delusion, and this generation of politicians may be even more subject to delusions than any before them.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on February 25, 2015 13:25

February 24, 2015

Business is no longer Conservative - this is why

I've written a blog on the Lib Dem Voice site today explaining the background to the pamphlet which I wrote with the investor Joe Zammit-Lucia, after the series of events he organised to allow businesspeople to talk more informally to politicians.

The idea is that business is an increasingly radical force, no longer tethered umbillically to the Conservative Party. Hence the title of the pamphlet, A Radical Politics for Business, which we launched at a business reception in London on Monday night.

You can read the blog here and the pamphlet here.

But it is true that I ought to spell out why this counts as a new idea, or at least the revival of an old one. The idea of business as a radical force in politics, however careful they might be not to be political themselves, is unexpected for the following reasons:

First, this is not the way that the official organisations supporting business tend to explain it..

Second, this report happens to coincide with the nadir of the reputation of business in the UK, which may have been unfairly blamed for the failures of the banking and regulatory system in 2008, but which has also been tainted by the continuing scandals from Enron to Robert Maxwell’s pensions theft, insider trading, Guinness, and so on, where business has suffered for the sins of relatively few – and politicians have failed so far to shape a regulatory system that can distinguish the few bad apples from the bad barrels.

The point is that businesses are not widely understood to be radicals in any way.

Third, businesses have been known – for a century or so – as bastions of support for political conservatism.

Often, it is true, they have done this mainly for fear of the alternative. But it has usually been more than this. Businesses have been a bastion for conservatism in other ways too: business people have dressed conservatively. They have encouraged conservative living, thrift and hard work. They supported the status quo.

[image error]You might feel, after a century or so of business walking hand in hand with conservatism, that it would continue like that forever. But the signs are that a big change is happening, and there is no reason to think this is confined to the UK.

Something in that old relationship between business and conservatism has broken. Business wants openness to ideas. They want open borders. They want long-term thinking, not the insane short-termism of the political world. They increasingly want education that promotes practical vocations, rather than suppressing them. They want schooling that looks beyond basic skills – important as they are – and trains people to be entrepreneurial and creative, not just train them to mind machinery. In short, business is emerging as a different kind of political force altogether, and advocating something altogether more radical.

What is interesting about this shift is that it isn’t unprecedented. For most of the nineteenth century, business instinctively supported the radical force in UK politics. It was Liberal then, just as it is increasingly Liberal now.

But then, Liberals and Conservatives see business differently. Conservatism regards business as supporting the status quo. For Liberals, business has always been about change. It has always involved allowing new ideas to challenge old ones, for new innovations to challenge the entrenched ways of doing things. It has always meant that the small should be allowed to challenge the big. Conventional wisdom has to be challengeable, by ideas or entrepreneurs, which is why – as Karl Popper put it – open societies tend to be more adaptable than closed ones.

Conservatism wants business to achieve some sort of stability. Liberalism wants them to be resilient, aware that change comes from everywhere and is rarely predictable.

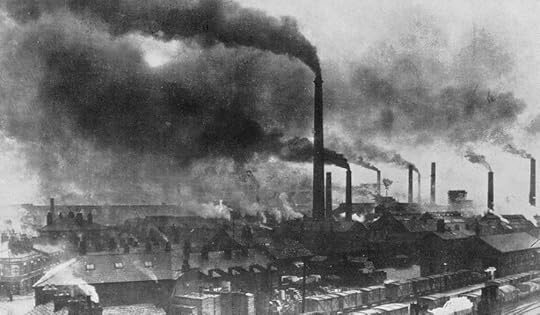

[image error]Victorian business, proud of and committed to their cities and towns, steeped in the ideals of self-help, was a radical force – politically Liberal, passionately committed to the idea that people should be able to do business where they saw fit, and determined to tackle the vested interests that prevented them (businesses are aware that there are rival vested interests out there now, just as there were in the nineteenth century). The political force behind ‘free trade’ has always been Liberalism. Free trade, that is, as it was originally understood – the right of the weak to challenge the strong.

If you are as fed up as I am by the assumption, particularly by the BBC, that business will always be Conservative - and the endless repetitive non-debate by the same old voices - then give the pamphlet a read. And talk about it in public.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

The idea is that business is an increasingly radical force, no longer tethered umbillically to the Conservative Party. Hence the title of the pamphlet, A Radical Politics for Business, which we launched at a business reception in London on Monday night.

You can read the blog here and the pamphlet here.

But it is true that I ought to spell out why this counts as a new idea, or at least the revival of an old one. The idea of business as a radical force in politics, however careful they might be not to be political themselves, is unexpected for the following reasons:

First, this is not the way that the official organisations supporting business tend to explain it..

Second, this report happens to coincide with the nadir of the reputation of business in the UK, which may have been unfairly blamed for the failures of the banking and regulatory system in 2008, but which has also been tainted by the continuing scandals from Enron to Robert Maxwell’s pensions theft, insider trading, Guinness, and so on, where business has suffered for the sins of relatively few – and politicians have failed so far to shape a regulatory system that can distinguish the few bad apples from the bad barrels.

The point is that businesses are not widely understood to be radicals in any way.

Third, businesses have been known – for a century or so – as bastions of support for political conservatism.

Often, it is true, they have done this mainly for fear of the alternative. But it has usually been more than this. Businesses have been a bastion for conservatism in other ways too: business people have dressed conservatively. They have encouraged conservative living, thrift and hard work. They supported the status quo.

[image error]You might feel, after a century or so of business walking hand in hand with conservatism, that it would continue like that forever. But the signs are that a big change is happening, and there is no reason to think this is confined to the UK.

Something in that old relationship between business and conservatism has broken. Business wants openness to ideas. They want open borders. They want long-term thinking, not the insane short-termism of the political world. They increasingly want education that promotes practical vocations, rather than suppressing them. They want schooling that looks beyond basic skills – important as they are – and trains people to be entrepreneurial and creative, not just train them to mind machinery. In short, business is emerging as a different kind of political force altogether, and advocating something altogether more radical.

What is interesting about this shift is that it isn’t unprecedented. For most of the nineteenth century, business instinctively supported the radical force in UK politics. It was Liberal then, just as it is increasingly Liberal now.

But then, Liberals and Conservatives see business differently. Conservatism regards business as supporting the status quo. For Liberals, business has always been about change. It has always involved allowing new ideas to challenge old ones, for new innovations to challenge the entrenched ways of doing things. It has always meant that the small should be allowed to challenge the big. Conventional wisdom has to be challengeable, by ideas or entrepreneurs, which is why – as Karl Popper put it – open societies tend to be more adaptable than closed ones.

Conservatism wants business to achieve some sort of stability. Liberalism wants them to be resilient, aware that change comes from everywhere and is rarely predictable.

[image error]Victorian business, proud of and committed to their cities and towns, steeped in the ideals of self-help, was a radical force – politically Liberal, passionately committed to the idea that people should be able to do business where they saw fit, and determined to tackle the vested interests that prevented them (businesses are aware that there are rival vested interests out there now, just as there were in the nineteenth century). The political force behind ‘free trade’ has always been Liberalism. Free trade, that is, as it was originally understood – the right of the weak to challenge the strong.

If you are as fed up as I am by the assumption, particularly by the BBC, that business will always be Conservative - and the endless repetitive non-debate by the same old voices - then give the pamphlet a read. And talk about it in public.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on February 24, 2015 12:00

February 23, 2015

Inventing new kinds of money to save the Greeks

It is sad but true that economic innovation is usually born of desperation. This is at least partly because the elite clings to the economic consensus with fervent, increasingly theological conviction, and all the more so as the consensus gets ragged around the edges.

It is sad but true that economic innovation is usually born of desperation. This is at least partly because the elite clings to the economic consensus with fervent, increasingly theological conviction, and all the more so as the consensus gets ragged around the edges.So perhaps the best we can say about the impasse between Greece and the European finance ministers, grappling with the implications of the disastrous design of the euro, is that it might perhaps - well, perhaps - lead to important money innovation. Well, it is about time.

Keynes used to call living in an economy without enough money a "perigrination in the catacombs with a guttering candle". That is the situation in Greece right now, and they are expected to carry on with this wander through the catacombs so that the euro might survive, and we will sleep more soundly in our immediate economic futures.

The question is whether these things can be achieved without the embalming of the Greeks.

The new Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis has been suggesting ideas, notably his proposal for a new currency, denominated in euros, but based on the future taxes paid to the Greek government, and designed to use bitcoin style block-chain technology to bypass the banks.

The details are obscure and perhaps too generous. The new currency pioneers are debating it all online. Varoufakis is suggesting that Greeks will be able to buy 1,000 euros worth of what he calls FT-coin in return for 1,500 euros worth of taxes paid in two years time. Maybe too generous, but it is an exciting idea and a sign that - at long last - those flung into the economic mainstream are beginning to think creatively again. See Paul Mason's take on it in the Guardian today.

It would mean monetising Greece's debts, taking them out of the hands of the banks and providing a machine that can potentially pay them off.

I'm not arguing that this will work, but I see that Shann Turnbull, the Australian financier, is set to speak in Athens. He is one of the most creative monetary thinkers on the planet, and it is time people gave him the benefit of the doubt and began to listen.

I know from listening to him myself that he will start by telling the story of the great American monetary innovation designed to help the poorer parts of the USA escape the Great Depression, thanks to the efforts of Alabama senator John Bankhead, Tallulah's uncle (it is Tallulah pictured above).

Bankhead borrowed the idea from the great economist Irving Fisher, and his bill - vetoed by Roosevelt - would have issued $1 billion of stamp scrip in the poorest areas. This kind of money encouraged spending by losing value by 1 per cent a month, and was eventually 'retired' - or deleted as we might say now - rather as the FT-coin would be when it was finally spent.

This is from Fisher's 1933 book Stamp Scrip (there isn't even a copy in the British Library):

"At my grandmother's country house, fifty and more years ago, you quenched your thirst at the spout of an old-fashioned wooden pump. To compel this huge creature to pour out its crystal treasure was no easy task for a small boy. It always involved a preliminary period of exercising the lofty handle, and sometimes quite without results, until an older person pointed out a bucket which stood near with a small side-supply of water. It was kept on hand for just such emergencies. Then the small boy would run to the side-supply scoop up a dipperful, climb upon any convenient object and empty the clipper into the open top of the pump. When he returned to his exertions they were no longer in vain. One scoop of side-supply had connected the big subterranean supply with the means of jerking it out of hiding. The strategy was called 'priming the pump'. This done, there was no further use for the side-supply. Such is the office of Stamp Scrip - to prime the pump, which has thus far been unable to connect the great supply of credit currency with the thirsty world."

Of course, you just can't just use the pump with euros. It would be inflationary. It would lower the value of the currency. The European Bank would not allow it. But you can experiment with new currencies and new denominations, based on a range of local items, and only starting perhaps with the Greek national debt.

But the Greeks must live, and if they can't live as perpetual captives in the catacombs for the good of the rest of us, then it is time to innovate. Or bring dishonour and disorder down on all our heads.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on February 23, 2015 01:24

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.