David Boyle's Blog, page 35

May 19, 2015

Come and talk about circular economics

Perhaps the first management consultant was James Oscar McKinsey, a US army logistics officer who became a professor of accounting at Chicago University after the First World War. A lone and exhausting copy of his text book on accountancy is still available in the British Library.

Perhaps the first management consultant was James Oscar McKinsey, a US army logistics officer who became a professor of accounting at Chicago University after the First World War. A lone and exhausting copy of his text book on accountancy is still available in the British Library.McKinsey thought that rigorous measurement could help companies find new strategies. But he had great charisma and huge confidence, and he took the risk of launching himself on his own to apply his ideas to other companies. He set up McKinsey and Co in Chicago in 1926, coming a cropper in his contract with a Chicago department store, and expiring shortly afterwards.

It was one of those thrilling periods of economic expansion and accountancy was busily transforming itself from an art into a science. The very first accountant in America, James Anyon, gave a valedictory speech in 1912 urging his successors to “use figures as little as you can”. “Remember your client doesn’t like or want them,” he said, “he wants brains.”

But Mac, as he was called, didn’t see it that way. It has never been clear quite who coined the McKinsey slogan ‘everything can be measured and what can be measured can be managed’, but that was certainly what McKinsey believed.

The huge global influence of the company that he founded, after more than 80 years, is now clearly apparent – not just in most of the biggest companies in the world – but many of the most powerful governments too

The impact of that slogan is also everywhere, and that goes some way to explaining why we are still chopping up aspects of work into measurable chunks and exercising increasing control over the people who put them into effect. It explains a little about why, despite all the vast investment in IT, human capacity seems to have become so seriously constrained.

Because the McKinsey slogan is a fallacy: everything can’t be measured. In fact, the more important it is – love, education, wisdom, imagination – the less it can be measured, and the more disastrous the attempt to do so tends to be.

To the extent that McKinsey follows the dictates of its own fallacy, it is responsible for so much that doesn’t work in the world we live in. More on this in my book The Human Element.

So I was pretty staggered to find this relatively enlightened article on their e-newsletter, setting out the principles of a circular economy, where waste is used as the raw materials for the economy. It is the best hope for economic activity that doesn't damage the climate.

This is the very kind of intellectual breakthrough that the McKinsey fallacy discourages in organisations. It's important.

I remember when I first heard the idea, from a Dutch geographer called Tjeerd Deelstra in about 1987. It seemed to me then, and seems now, absolutely fundamental to the future. It may also provide the missing resources that impoverished areas need to claw themselves out of dependency.

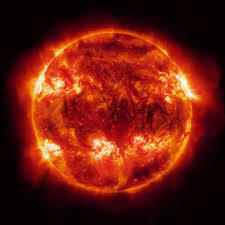

It also has another implication: a shift from using raw materials to using technology. We are already shifting in this way over energy: gas and nuclear fuels (getting more expensive) to solar technology (getting cheaper).

This is all a rather complex way of saying that I'm discussing the circular economy tomorrow, together with my New Weather colleague Andrew Simms at the Hay Festival and it would be very good to see you there and hammer this out a little further. It's called 'Cloudy with a chance of compost' and it is at 4pm (21 May).

I'm doing a follow up meeting on 29 May at 11.30am (Stormy with a sunny local banking outlook) with Andrew and Caroline Lucas.

And while we're about it, if you happen to be in York the following day, at 4pm on 30 May, you can see part of my musical (with Naomi Lane, Danube Blues) at the New Musicals Festival. More on that later.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 19, 2015 01:42

May 18, 2015

The elusive, missing political ingredient

I wrote last week about the experience if hearing the former Liberal Party president Adrian Slade, a former Footlight, imitating Roy Jenkins during the 1982 party assembly in Bournemouth.

I wrote last week about the experience if hearing the former Liberal Party president Adrian Slade, a former Footlight, imitating Roy Jenkins during the 1982 party assembly in Bournemouth.It was the first time I had been to any national Liberal event and I wasn’t sure what to expect, had no idea that Slade had entertained successive assemblies with his songs, but I was hooked. It was also the first full year of the Liberal-SDP Alliance – hence Adrian’s other creation that year ‘Social democracy, what the hell is it meant to be?”

This included the immortal and suddenly relevant lines: “We know how to win them,/And we know how to lose them”.

At the height of the performance as Jenkins, the man himself walked in ,as a gesture of solidarity with his Liberal allies. He wrote later that it was the nadir of his Alliance years. Especially perhaps Slade's line about his “great crusade to change everything... just a little bit”.

Now I’m all for moderation and compromise, as long as it is a small part of a greater ambition. At least, that’s what I thought as I read Stephen Tall’s contribution on this very subject, which he called ‘Why the Lib Dems should stick to centrism’ (I’ve shortened this, but you get the gist).

In this blog post, he wrote positively about an economic policy in which “free enterprise is balanced by workers rights”.

I have huge respect for Stephen Tall, who is a very talented and inspiring blogger. More than that, he was a fellow candidate with me for Horsham Borough Council this year in the Lib Dem interest. But I wanted to take this a bit further.

I very much agree that Liberals need to be centrist in the sense that they must not veer towards either a conventionally right or left wing stance. But the economic policy he advocates here isn't centrism, it is compromise, and it is so anodyne that it is hardly worth saying.

It goes in one ear and out the other. It is, in short, like saying nothing on economics at all. Just laying it on one side and talking about something else.

Does that matter? Well, actually, I think it matters very much.

There is a parallel debate in the Labour Party which gargles with the irritatingly Blairite phrase ‘aspirational people’, as shorthand for what Ed Miliband missed out. It carries within it a quite unnecessary class baggage, as you might expect from a Labour Party debate.

Where it applies equally to Labour and the Lib Dems is this.

No political party can make a successful appeal to the electorate without some kind of economic proposition. You can’t just talk about welfare, important as that is, and feel you have somehow put forward a plan for prosperity.

This is a problem for the left everywhere. There is no alternative narrative, no convincing package, explaining how we would create prosperity. Leftist governments have been elected in the past three decades, but only by embracing the conventional economic message.

No political party can aspire to government without a convincing plan to create a prosperous economy. Not just how to spread the money, or just how to spend it, but how to create it.

In the absence of one, people revert to the lazy assumption that the Conservatives can create prosperity, thought there is little evidence that they can. But we allowed them to get away with it without putting forward a Liberal economic approach. Because there isn’t one.

Or is there?

I realise I'm about to fall into Stephen's trap, arguing that the missing element in the election campaign was exactly what I've been advocating for years.

So let's try and set that aside. Because, there was - until the 1950s - a distinctive Liberal approach to creating prosperity. We just got bored of it. Liberals let it atrophy.

It is an approach to economics based on the same Liberal principles that we use for everything else: Karl Popper’s idea of the open society, where the small must be allowed to challenge the big, and the poor, powerless and local must be able to challenge the rich, powerful and central.

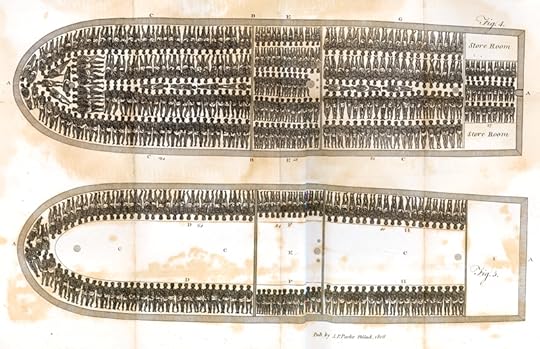

That is the original meaning of the Liberal concept of free trade, which emerged originally out of the anti-slavery movement as a critique of monopoly, a guarantee of the right to challenge from below.

It is the fault of Liberals everywhere that they have allowed this powerful economic idea to become an apologia for monopoly, a justification of it, a circular argument that monopolies must have earned their position and must be defended – though they narrow choice, raise prices, trap or bypass the poorest, and shrink the economy.

The latest US research shows that regional and local economic growth is highly correlated with the presence of many small, entrepreneurial employers—a few big ones may be positively damaging. See my new book People Powered Prosperity.

This would imply a Liberal challenge which was both pro-enterprise but at the same time confronting the privileging of semi-monopolistic corporates by both Labour and Conservative, which has sucked some local economies dry, making them so much more dependent on central government.

It would imply a Liberal approach that was neither conventionally right or left, but which is emphatically not a compromise:

It would be based on a major expansion of small business and enterprise, and of the institutions that entrepreneurs need: local banks, enterprise support, mutual support, maybe even mutual credit.It would mean a genuine rebalancing of the economy away from finance and property and towards productive capacity (see recent IMF report that too much finance damages an economy).And it would mean a major monopoly-busting measures to give people better choice and more vibrant, diverse local economies.

See how Joe Zammit-Lucia and I put it in our recent pamphlet.

That is powerful, distinctive and overwhelmingly Liberal. It also has the benefits of being right. But don't let's pretend we can be a major opposition party without putting forward some approach to creating prosperity. The truth is that we know how to, acted on it in government, but never really articulated it.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 18, 2015 02:18

May 14, 2015

Nick Clegg: our part in his downfall

I first met Nick Clegg after I wrote a pamphlet for Liberator in 2000 about how we might re-imagine a political party which could, once again, have a mass membership. He was interested in ideas. I liked him enormously.

I first met Nick Clegg after I wrote a pamphlet for Liberator in 2000 about how we might re-imagine a political party which could, once again, have a mass membership. He was interested in ideas. I liked him enormously.I have only spoken to him twice since he became deputy prime minister. You can't really be friends with senior politicians. You have to devote yourself completely to their cause and be useful to them. I don't blame him for this: it's the nature of the job and, also, I did rather let him down a couple of times.

But I have a memory before that of how he thought. Wrestling with new ways forward. Sceptical in a positive way that is actually very unusual for working politicians. He was a gut Liberal and I'm sure he still is.

I believed at the time, and still believe, that he was the right choice as leader. We needed a thinker, which is what I wrote during his leadership campaign in my first ever blog post here in 2007.

We still do need a thinker (which is why I will be supporting Norman Lamb). It wasn't that Clegg failed to fulfil this role. It was, as DPM, that he was locked in a Whitehall office with an agenda that required a minute by minute response. It wasn't exactly conducive to thinking, so the thinking still urgently needs doing - and at least as much as the campaigning.

The trouble with departing swiftly after a major setback is that you tend to get the blame for it, and we have already seen those - from David Steel downwards - who have seen this as the moment to blame Clegg.

Not only do I think that is wrong, it is also rather shortsighted. Because I believe, in his political skill, his eloquence, his humour and his unique ability to sound human, Nick Clegg was the most effective leader the Liberal force has had in this country since the Second World War. I don't want to lose those elements of the party's personality that he pioneered.

I have seen tributes to his integrity, and they are absolutely correct - who else would have taken care to choose his words so carefully that he did not betray a confidence from a political opponent on the Today programme, when the temptation to do so must have been overwhelming?

But if we think back over the TV debates, his performance in 2015 was extraordinary - passionate, articulate but also human. That is such a difficult trick to pull off for a politician, and it is cruel and unjust that he did not reap the benefit of it.

His great skill has been to see how policy objectives might be achieved, despite the mess of the government system, and despite the opposition from his coalition partners. The idea of localism by individual City Deals, which he masterminded, has made a huge difference.

I'm not, of course, endorsing every campaign decision in 2015, or every decision the coalition made. It is so easy in hindsight to say what should have happened.

Of course the tuition fees business, which has ended up giving us a more successful and fairer policy, could have been managed better - and perhaps would have been after a few more months experience. But before history hangs that like an albatross around Nick Clegg's neck, let's just remember that he warned the party not to adopt the abolition position.

They took no notice. And here I had a personal part to play as a member of the Lib Dems' federal policy committee, and I should confess it. Along with a majority of other members of the committee, I voted to carry on the policy to abolish tuition fees - even though the leader had warned us of the consequences.

The consequences happened.

Actually, it is worse than that. When it came to the moment, before the 2010 election, I couldn’t decide how I ought to vote on tuition fees, and I’m not absolutely sure I did vote to maintain our policy against tuition fees or not. Such an important decision, as it turned out, and I can’t remember what I did.

There we are. That's my confession. The truth is that the defeat the party just suffered was a defeat for the party as a whole, not just for the leader or the strategy.

It was also the culmination of an intellectual and electoral decline which had been going on for a decade. Clegg took the party, turbo-charged it suddenly, took a place in government for the first time since 1916, managed it magnificently. But the basic trends have been downwards since the turn of the century.

But why are the critics shortsighted? Well, here's my prediction, and it is inspired by the latest blog on the New Statesman's website. The period when Clegg was deputy prime minister will soon be regarded as a brief shining moment of civilisation, successfully steering the economy to some kind of security, and pioneering major economic and educational shifts that will stay with us.

That understanding will happen much sooner than most of us expect.

It isn't a proper reward for the former party leader, but it is at least fully deserved. I feel very proud to have been a member of the party when he led it.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 14, 2015 00:52

May 13, 2015

It's time we renamed the Lib Dems

There is a well-known story about George Bernard Shaw and Ellen Terry, which her biographers have dismissed as apocryphal. But then Shaw was always complaining about being importuned by women, so who knows.

There is a well-known story about George Bernard Shaw and Ellen Terry, which her biographers have dismissed as apocryphal. But then Shaw was always complaining about being importuned by women, so who knows."We should have a baby," she is supposed to have told him. "Then it could have my looks and your brains."

Ah yes, said Shaw - "but what if it had my looks and your brains?"

I was reminded of this in the last few days of the general election campaign, with the Lib Dems producing tweets with characters from the Wizard of Oz, offering to be the brain of Labour and the heart of the Conservatives.

Ah yes, I wanted to say - but what if we ended up as the heart of Labour and the brains of the Conservatives. A terrible fate, one of them sentimental, mushy, deeply old-fashioned and rather intolerant. The other atrophied from lack of use.

The trouble with the heart/brain analogy was that you wanted to probe more deeply. Yes, you want to be the heart of one and the brain of the other - but what are you?

There was something unnerving about it, in retrospect. Like someone coming to your door and telling you that they could be whatever you wanted them to be.

In the same way, the strange - slightly Vichy-esque - triptych, Stability, Unity, Decency, which the Lib Dems adopted in the final hours of the campaign, begged the question. Stability for what? Unity for what? Not, surely, for their own sake. They were the means to an unstated end, an unarticulated objective.

But I have been wondered whether the problem is deeper than that, and lies in the basic dualism that has fractured the party in recent years.

Orange Bookers versus Social Liberal Forum types. Unresolved issues between Libs and Dems. Hearts versus brains. As if we are somehow expected to choose one or the other.

I don't know if Tim Farron was

There have always been divisions between the Whiggish types who cluster around the top of the party and the Distributist types, localist, individualist, able to knit together an economic approach and a way to tackle tyranny and slavery. These are the traditional divisions: they have been pushed out a little by the new Lib and Dem shorthand - a sort of small C conservative version of social democracy that sees little further than defending the institutions of the 1970s.

By suggesting that the party reverts to its original Liberal name, I'm not choosing right against left. Quite the reverse, in fact. I'm old enough to remember when the Lib represented the radicals and the Dem represented the line, caricatured by Adrian Slade at the 1982 Liberal assembly in Bournemouth.

Slade pretended to be Roy Jenkins, perhaps unaware that Jenkins would arrive in person, together with David Steel, whose wife Judy then emphasised the embarrassment with a very public giggling fit.

At the height of his peroration, Slade-as-Jenkins described the Alliance as a "great crusade ... to change everything ... just a little bit".

There is the besetting sin of the Lib Dems, to aspire to change everything just a little bit. At least, I think that is how the public perceives it sometimes.

So I propose that the party launches itself again under its original name, which was after all a proud name - with a great tradition - so that we should no more struggle to hold the two sides together, heart and brain, Lib and Dem and should wrestle to articulate one approach.

Continuing as Lib Dems simply perpetuates the unresolved dualism. It is lazy; it allows both sides of the divide to wallow in their own versions of conservatism - whether it is defending the 1970s or defending the 1860s (apologies for the caricatures). We need to be forced to be coherent, to hold the two sides together in a new synthesis. One approach which looks ahead.

One approach that also has to embody the elusive philosopher's stone of the Left - a convincing, effective approach to creating prosperity. That's what we need to shape and articulate, and it will help us to do so with a party name that doesn't start off by emphasising that it's a compromise.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 13, 2015 01:12

May 12, 2015

Reasons to be less cheerless

[image error]

There was William Morris in 1888, putting the finishing touches to his first medieval fantasy novella, A Dream of John Ball.

Morris, the great socialist and wallpaper designer, was by then thoroughly disillusioned with Liberalism, and he dreamed that he had hurtled briefly back to the Peasants Revolt. There he had encountered the preacher who inspired it, John Ball, and spent the night with him in a darkened church, surrounded by the bodies from the first brief encounter with the enemy, talking about the future.

Afterwards, the encounter gives Morris an extraordinary perspective on history:

"I pondered all these things,” he wrote, “and how men in fight and lose the battle and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat. And when it comes, turns out not to be what they meant and other men have to fight for what they meant under another name.”

Morris was right, and he seems to have hit on a profound truth about politics. Change is deeply paradoxical, and – although the grammar of progress eludes most politicians – we achieve what we achieve sideways, like crabs.

When we win we are also at the moment of disappointment; when we lose then paradoxically things happen as a result. It’s confusing, but that is how it works.

Don't get me wrong. This isn't a reason to be cheerful exactly. Nothing so extreme. But it might be a reason to see the current political setback more objectively.

So here are my three reasons to be less cheerless.

1. Things will happen quickly. David Steel said that the Lib Dems would take two decades to recover. I don't think he's right, and for all the reasons Duncan Brack set out. It was less than 18 months between the ignominy of fourth place behind the Greens in the 1989 Euro-elections and the 'dead parrot' verdict on the party, and victory in the Eastbourne by-election in October 1990 ("well, the parrot twitched," said a Tory spokesperson).

Within four years, and two years after the disappointing general election of 1992, you could walk from Land's End to Winchester on land represented at some level or other by Lib Dems - a huge yellow swathe across Wessex, capital city: Yeovil.

2. The Labour Party is crumbling. An amazing map, developed I think by Vaughan Roderick from BBC Wales, compared Labour constituencies in 2015 with former coalfields. Apart from London, the comparison is extraordinary. What I take from this is that Labour has now shrunk back down to its absolute heartlands, apart from its seats in the capital. This is graphic evidence that there is no longer a coherent Labour proposition, no uniting conceot, no obvious purpose.

This does not, of course, guarantee that the Lib Dems will provide a way forward either, but the opportunity is there to be grasped.

3. We are due for a major intellectual shift. I have had a go at this idea before, but these major economic shifts happen regularly every 40 years - 1831, 1868, 1909, 1940, 1979, which means we are due for something similar in around four years time. They are hardly uncontroversial shifts when they happen - the People's Budget split the nation; so did monetary economics and the end of exchange controls. But they are big shifts, and they are permanent for four decades or so.

They can't happen out of the blue. There has to be some work, some proposals, some emerging consensus, some direction before the shift can take place. But it will happen, and probably in this parliament.

So hold onto your hats.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Morris, the great socialist and wallpaper designer, was by then thoroughly disillusioned with Liberalism, and he dreamed that he had hurtled briefly back to the Peasants Revolt. There he had encountered the preacher who inspired it, John Ball, and spent the night with him in a darkened church, surrounded by the bodies from the first brief encounter with the enemy, talking about the future.

Afterwards, the encounter gives Morris an extraordinary perspective on history:

"I pondered all these things,” he wrote, “and how men in fight and lose the battle and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat. And when it comes, turns out not to be what they meant and other men have to fight for what they meant under another name.”

Morris was right, and he seems to have hit on a profound truth about politics. Change is deeply paradoxical, and – although the grammar of progress eludes most politicians – we achieve what we achieve sideways, like crabs.

When we win we are also at the moment of disappointment; when we lose then paradoxically things happen as a result. It’s confusing, but that is how it works.

Don't get me wrong. This isn't a reason to be cheerful exactly. Nothing so extreme. But it might be a reason to see the current political setback more objectively.

So here are my three reasons to be less cheerless.

1. Things will happen quickly. David Steel said that the Lib Dems would take two decades to recover. I don't think he's right, and for all the reasons Duncan Brack set out. It was less than 18 months between the ignominy of fourth place behind the Greens in the 1989 Euro-elections and the 'dead parrot' verdict on the party, and victory in the Eastbourne by-election in October 1990 ("well, the parrot twitched," said a Tory spokesperson).

Within four years, and two years after the disappointing general election of 1992, you could walk from Land's End to Winchester on land represented at some level or other by Lib Dems - a huge yellow swathe across Wessex, capital city: Yeovil.

2. The Labour Party is crumbling. An amazing map, developed I think by Vaughan Roderick from BBC Wales, compared Labour constituencies in 2015 with former coalfields. Apart from London, the comparison is extraordinary. What I take from this is that Labour has now shrunk back down to its absolute heartlands, apart from its seats in the capital. This is graphic evidence that there is no longer a coherent Labour proposition, no uniting conceot, no obvious purpose.

This does not, of course, guarantee that the Lib Dems will provide a way forward either, but the opportunity is there to be grasped.

3. We are due for a major intellectual shift. I have had a go at this idea before, but these major economic shifts happen regularly every 40 years - 1831, 1868, 1909, 1940, 1979, which means we are due for something similar in around four years time. They are hardly uncontroversial shifts when they happen - the People's Budget split the nation; so did monetary economics and the end of exchange controls. But they are big shifts, and they are permanent for four decades or so.

They can't happen out of the blue. There has to be some work, some proposals, some emerging consensus, some direction before the shift can take place. But it will happen, and probably in this parliament.

So hold onto your hats.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 12, 2015 02:02

May 11, 2015

Liberalism isn't dead, it's just been hit by a truck

"We're British people, with all their qualities and faults, with feelings and emotions, and not denationalised, impersonal polyglot cynics with the generous emotions of a fish, intimidated by fears that what we feel like saying will be 'bad propaganda'."

"We're British people, with all their qualities and faults, with feelings and emotions, and not denationalised, impersonal polyglot cynics with the generous emotions of a fish, intimidated by fears that what we feel like saying will be 'bad propaganda'."Any guesses? It was the morning directive written by the director of the BBC European Service, Noel Newsome, on the news of the fall of Singapore in 1942. It isn't quite how we would express ourselves now, but I thought of it on Friday after the news of the general election results.

Newsome led a staff of 500, broadcasting in more than 30 languages, the biggest broadcasting operation in the world, then and now. He was also a Liberal. He believed that, for the BBC news to sound authentic across occupied Europe, it must not be spun. It had to sound British. It's origins had to be obvious. It was a sophisticated and controversial point of view.

I think he was right. You have to be human about these things. You can't spin them. You can't pretend, as Nigel Farage did, that you somehow don't mind.

That was, anyway, my feeling when I was woken at 5.45 on the morning of May 8 by the Guardian, asking me to write about it for Comment is Free. I had an hour or so to work out what other disasters I had missed in the previous few hours and get my thoughts together. Here it is.

I was pleased, of course, that they decided to publish it again in the paper the following morning. But nervous.

For one thing, my raw feelings of 24 hours before had changed somewhat. I'd begun to see things a little more clearly. For another, they stuck a headline on which said that the Liberal project was 'dead', which I emphatically didn't believe, and didn't say.

Yes, it had been hit by a ten-ton truck, and was in intensive care, but it was definitely, emphatically, still alive.

I was also little ashamed that I was wallowing in my own grief - and the results felt to many of us like a bereavement - when I had it easy compared to so many others. I had not given years of dedicated, imaginative and tough-minded service to the nation and the party, only to find myself out of office and out of a job - and on television too.

People who had genuinely made a difference like Danny Alexander, or pioneered the revival of apprenticeships like Vince Cable, or been a brilliant and much-loved MPs like Tessa Munt and Martin Horwood and Andrew George and so many others. It seemed so desperately undeserved. I will write about Nick Clegg in a few days' time, but I feel particularly proud to have been involved in the party under his leadership.

No, they didn't get everything right - who does? - but my goodness they tried, and nothing I wrote should detract from that.

I have realised in the last few days how much I have needed to believe, throughout my adult life, that the world was improving, the causes I've devoted so much energy to growing in strength. To encounter such a setback has been a profound shock for many of us - especially as we are now ruled by an elected-yet-unelected selection of privileged people who don't understand the modern world, and whose power is now unfettered.

But I'll tell you what I did. I went for a long walk last night, up on the past behind my house and onto the South Downs Way, the old white track used back to the Stone Age. It put these disasters into the context of history. A little. History fluctuates, after all.

Speaking of which, I keep thinking of the 1945 general election as a disappointment for Liberals almost as great as 2015 - reduced to 12 seats, a charismatic leader who had been a successful coalition minister, a campaign focusing on international issues when the voters wanted to hear about social ones, and huge Liberal hopes...

Noel Newsome, mentioned above, left his job running Radio Luxembourg to contest Penrith and Cockermouth for the Liberals and came within 2,600 votes of unseating the sitting Conservative. These days, the seat is next to Tim Farron's where he managed to win more than 50 per cent of the vote on Thursday.

More of Newsome another day. In the meantime, I hope those non-Liberals who read this blog will forgive me for my single-minded focus on Liberalism for the next few days - I can't help it...

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 11, 2015 01:32

May 8, 2015

First thoughts on electoral disaster

The Liberal Revival has been woven through my life, and especially my adult life. I wrote this in the early hours of this morning for the Guardian Comment section.

Published on May 08, 2015 02:26

May 7, 2015

Yes, B and C grades are certainly saner

I'm coming to the conclusion that the Great British Public (they don't call it that any more) is not nearly as switched off the election as we are given to believe. Everyone I know seems to be wrestling with it, and their specific decision.

I'm coming to the conclusion that the Great British Public (they don't call it that any more) is not nearly as switched off the election as we are given to believe. Everyone I know seems to be wrestling with it, and their specific decision.They are not wrestling with the issues, exactly. They are wrestling with the BBC version of the election - a decision between various different marketing strategies. Another thing entirely.

I find that gap frustrating but, finally, I ran across a story which sums up the issues for me. It is the one about exams. This is what the Evening Standard wrote:

"Teenagers should settle for B or C grades and not strive for perfection in every subject, the head of a London private school says. Heather Hanbury, headmistress of the Lady Eleanor Holles School in Hampton, said parents and pupils now view A and A* grades as the norm, which devalues results and harms students’ self-esteem. Perfection is only occasionally a worthwhile aim, Mrs Hanbury said, and knowing when something is “good enough”, and keeping a sense of perspective, are 'essential life skills'. Instead of completing every piece of homework perfectly, Mrs Hanbury advised students to settle for a lower grade and spend more time on extracurricular activities such as sport..."

A few points about this. Heather Hanbury is exactly right. She is also flying in the face of everything which is believed, and has been believed for the nation, by the great triumvirate that rules us: the Conservatives, the Labour Party and the civil service.

For them, education has been a utilitarian affair, measured by the inadequate indicators which are used solely because they can be measured. We have lived through management by numbers, by targets, and a great dullness spread across the school system. It wasn't about life, or even finding ways to live life better - it was about showing up well in the Prime Minister's graphs.

But the coalition came and they invested in schools - and, thanks to the Lib Dems, launched the pupil premium. But they did not fully understand the damage that the technocratic worldview in New Labour was doing to education - or the rest of public services. They did not grasp the dangers of services designed like assembly lines. In education, it means narrow outlooks, narrow horizons, ignorance and insane specialisation.

Worse, they allowed some schools to pay bonuses to teachers for good SATS results, turbo-charging the soullessness, damaging rounded education and dulling-down the classroom. Transforming children from the beneficiaries of individual attention into the means by which teachers could achieve their bonus results.

So, yes, Heather Hanbury is right. In the name of Tony Blair's 'modernisation', we have actually nudged education backwards. Not everywhere - my children's primary schools are brilliant, imaginative models of their kind.

But here is what worries me. Why does this saner approach have to be articulated in public by an independent school headteacher? Why are we not allowed to have state headteachers publicly rejecting the wisdom of their bureaucracies? And why has this critical issue - the critical issue for me - played no role in the election debate whatsoever?

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 07, 2015 01:02

May 6, 2015

Independent schools: no longer for the likes of us

I went to a school reunion last weekend. I'm not sure why these events are so nerve-wracking - perhaps we are afraid of encountering our own age and failures in the faces of our fellows. In the event, of course, everyone was exactly the same.

I went to a school reunion last weekend. I'm not sure why these events are so nerve-wracking - perhaps we are afraid of encountering our own age and failures in the faces of our fellows. In the event, of course, everyone was exactly the same.Some of us meet up anyway every few months. We are middle-aged, middle class survivors, in a sense. Some of our fellow public schoolboys from the 1970s have died. One or two have even committed suicide, but we are still around, largely happy, not always thriving, but settled. What is most unexpected about the small group of us who meet more often is how diverse we are.

There are two builders, a furniture restorer, a very successful barrister, a medical consultant, an Alexander Technique teacher, and a writer (me). There is also a fireman, an undertaker, a sales director, and an engineer, among others. I'm sad to say the garage owner just died.

We spent our whole schooldays being told how privileged we were, and we were certainly privileged in many ways – most of us own our own homes. But if you believe the rhetoric about independent schools, on either side of the political divide, you might have expected us to have been more of a cohesive group.

We're not the narrow slice of the class system you might have predicted. We seem actually to straddle a huge variety of different kinds of middle classes, but we all worry about our children, and their ability to survive in the world that is emerging, here and abroad.

More about this in my book Broke: How to Survive the Middle Class Crisis. But back to last weekend.

The highlight of the dinner was the headmaster's speech, inevitably asking us for money for scholarships and explaining - rather oddly actually - that the huge rise in fees since the days when we went there were unavoidable.

The explanation he gave for this was the rising cost of regulation. They now include in the staff two full-time compliance officers.

I'm sure this is onerous, but the fees for boarders hover around £30,000 a year. At that rate, you only need two or three extra pupils to pay the costs of the compliance officers. No explanation why they need 17 all-weather pitches.

I have nothing but goodwill towards my old school, to which I owe a great deal. I have nothing in principle against independent education either. It would be hypocritical of me, and anyway I believe in as much diversity in education as possible.

But it is time to accept that the independent sector is not really for the middle classes any more. That was certainly the conclusion I came to making Clinging On for the BBC, when I visited the Independent Schools Fair in Battersea Park and asked anyone I met to describe the parents who could afford it - mainly foreign, they said. In oil or finance.

Already a third of independent school pupils are getting help with fees. It doesn't look good. The truth is that the sector has let down the middle classes which used to rely on it as an alternative, rather as they relied on the BBC to keep up broadcasting standards.

I don't take much comfort that a major element of educational diversity has been handed over to the ubermensch. As you can tell, I didn't find the speech by the headmaster terribly convincing. It was like being asked for a contribution to the coffers by HSBC's mergers division on the grounds that I had once enjoyed an account at one of their local branches.

It is part of my thesis in the book that the institutions which once nurtured the middle classes, and helped them thrive, have now gone - local banks, monopoly watchdogs with teeth, truly independent financial advisers, small-scale public services, affordable homes. They will have to be rebuilt, laboriously, all over again.

A pity we never heard that debated in the election campaign.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 06, 2015 02:34

May 5, 2015

Why is the election so po-faced?

There never was an election campaign in history, at least outside the USA, so desperately lacking in authenticity.

There never was an election campaign in history, at least outside the USA, so desperately lacking in authenticity.Yes, there are some exceptions. The revelation of SNP aggression last night, as they battered Jim Murphy and Eddie Izzard, did at least appear to be a glimpse of something real. Otherwise, it is exhausted slogans (exhumed from the 1940s), fake concern, and very, very careful politicians.

I found myself thinking about this a little more after the revelation of Ed Miliband's much-ridiculed tablet of stone. It revealed the need for something authentic - it was just that the words slipped through your fingers. The pledges were as good as meaningless.

The trouble is that these very careful words are there for a reason: fear of the other side's negative campaigning. Fear of the forensic interview or a hectoring tabloid.

One of the few national politicians who manages to wrap himself in the mantle of authenticity is Boris Johnson, mainly because he dares to use humour and, when the humour gives out, he uses the most dangerously lurid images. The idea of Ed Miliband with a monkey on his back stays with me, whether I like it or not.

But the authenticity of Boris is in doubt as well, rather as Tony Blair's authenticity was. Is it a skilful hoax? Is there anything there behind the mask? Does the man actually have any convictions at all? The jury remains out.

When I was writing about authenticity more intensely (see my book of essays The Age to Come ), I happened to hear one of Howard Dean's campaign managers interviewed on the subject. To seem authentic, he said, politicians need to go off message. Just occasionally.

Perhaps it's too much to expect them to do so now, 48 hours before polling. It is just so dangerous. But the rewards of getting it right are pretty high, if only they dared.

But I do find it strange that they don't even take the intermediate path, as Boris Johnson does. There are nations which might take offence when a politician makes a joke, or feel that the issues they represent have been demeaned. But we are not the USA: why are so few of our politicians being humorous?

I remember Lord Holme, who ran the Lib Dem campaign in 1997, making a specific point of making jokes at the morning press conference. He did so quite deliberately to differentiate the party from the others. Not politicians' jokes either - these can tend to be heavy-handed non-humour at their opponents' expense - but real humour of a more genuine and human kind.

Why are they so staggeringly po-faced? Do they really think that humour will undermine their own seriousness?

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on May 05, 2015 01:49

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.