David Boyle's Blog, page 37

April 15, 2015

Does anyone hear 1940s political language any more?

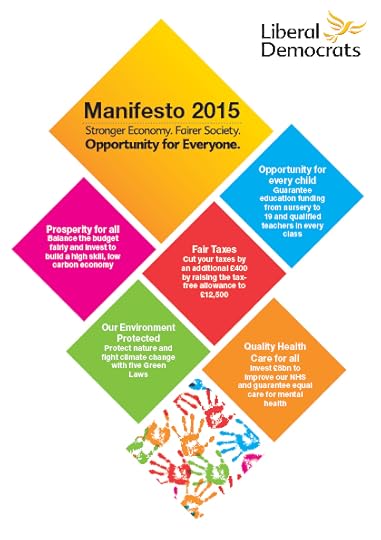

I have been reading the Lib Dem manifesto. Well, I had a couple of days to spare. And it is an impressive document. No political party can ever have written quite such a detailed manifesto before. I've been wondering why.

I have been reading the Lib Dem manifesto. Well, I had a couple of days to spare. And it is an impressive document. No political party can ever have written quite such a detailed manifesto before. I've been wondering why.In fact, the manifesto reveals what the Liberal Democrats have become after five years in coalition. Detail orientated. Deeply pragmatic. Determined to deal with the world as it is, not as it might be. It's great advantages are that some of the commitments are vital and bold - the commitment to zero-carbon Britain by 2050, for example. But there are disadvantages too.

It reveals itself as a document written in Whitehall. Its small commitments are spelled out in painful detail. Its big ones remain vague. It has figures running through the thing like a piece of Blackpool rock. And the language is old-fashioned: does anyone hear commitments in 1940s language - 'healthcare for all', 'prosperity for all' - any more?

Of course, this is not a document written for the public. It is a document written to be used in coalition negotiations, and as such it works very well. But it is so hard-headed a document that people may not feel like spending too long in the company of the party which drafted it, for fear that they will start spouting statistics at them.

Like other documents written in Whitehall, the authors forget how little people hear figures - especially when they involve amounts. Most people, in my experience, don't hear a difference between million and billion unless they are very familiar with the debate already.

I have to declare an interest - the two major proposals I have been working on for the past two years are both missing. This is very disappointing, but this isn't the moment to spell them out, and they are at least hinted at.

Perhaps the real problem is that it bears the scars from Whitehall battling over five bloody years. It assumes the existing arrangements, uses the word 'continue' rather too much, thinks ahead too little and does not even attempt to inspire. Its cover emphasises the failure to join up ideas.

Perhaps that is the right strategy this time. I don't know. But for all these reservations, it is a real achievement too. It is an extraordinarily comprehensive compendium of how we would bend the system, without too many running battles in the corridors of power. It leaves no doubt - and I realise this was the intention - that everything there is eminently achievable.

It is a hymn of praise to a highly complex system of government, and a commitment to change it a bit. Yet don't be under any illusion - if we have a zero-carbon Britain by 2050, and free school meals, and a new Freedom Act, and a network of community level banks, and many other things that are all in there somewhere, the nation will look very different.

I just hope people read it, but wonder...

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on April 15, 2015 06:47

April 14, 2015

Build more homes and then give them away

The Conservatives have announced an extension of the right to buy. It is an important, populist idea, but it carries within it a serious flaw. Enacted in the right way, it could be liberating. Imagine the shift in power if this was applied to private tenants too. Enacted in the wrong way, it will be inflationary, tyrannical and destructive.

So, instead of dismissing the idea out of hand, let's think about how something along these lines might be achieved, as it should be. Because the record of politicians over the past generation has left us a housing legacy so toxic (see Mark Jordan's television programme last night) that something demands to be done about it.

The Lib Dems alone have come out with at least three major policy announcements to help with the housing crisis, so the electorate might be forgiven for not remembering any of them. Which is a pity because, so far, the commentators have missed what is an important and innovative idea - and, for me, by far the most important proposal of the election so far. The proposal for rent-to-own social housing.

I can't think of any area of public policy where we needed something generous and imaginative which cuts through the usual tired old stuff more than we do in housing.

Here is the division, and you have to put it in stark terms - because both big parties of government (I'm referring, perhaps for the last time, to Labour and Conservative) support both these untenable positions.

Position 1. We need to extend home ownership. We do, of course, but the political rhetoric ignores the fact that it is plummeting like a stone because successive generations of politicians have done nothing about rising house prices - or the too plentiful finance pouring into the property market and pushing up prices to ruinous levels.

As I explained in my book Broke: How to Survive the Middle Class Crisis, home ownership - even in London - is now below Romania or Bulgaria. We are becoming dependent supplicants to the new landlord class, the rentiers which Keynes once told us deserved 'euthanasia'.

Position 2. We need more social housing. Again, we do. But again, this is all political rhetoric and battling by number, aware that - in the past (for example under Harold Macmillan) - high target numbers meant low quality housing which would become slums themselves a decade or so later.

Worse, the political rhetoric stops there, so that social housing becomes an end in itself. We trap poor people in ghettos, and leave them there, preventing their escape. And we congratulate ourselves, as a society, because we are providing social housing for rent. The quality of that housing for rent has been, certainly in my lifetime, deeply dehumanising high density places, where people are given little or no control over their environment.

That is the besetting sin of Labour housing policy. In fact, the appalling housing Labour built in Scotland over two generations explains a great deal about their difficulties as a party north of the border. See Labour's hutches for the dependent poor pictured above.

I've come to believe, as a modern Distributist, that the way forward has to be building new homes and then giving them away - on three important conditions:

They do not go back onto the open market and fuel house price inflation (ownership need not imply the right to sell).They stay at the same nominal price they were originally sold for, ratcheting down the rest of the market, perhaps for a generation or so.They are built in sufficient numbers to satisfy demand.Simply giving away social housing also works, but not if it fuels inflation and isn't replaced. But if the social housing is replaced, giving it away seems to me a more Liberal solution, given that it provides people with genuine independence. I've got no time for the idea that, because people are poor, they must be forced to pay rent.

Which leaves us with the issue of how it can be affordable. The Lib Dem solution suggests a model - rent-to-own, giving people progressive ownership rights thanks to the rent they pay. I'm only sorry they are only promising a pathfinding 30,000.

I'm also sorry that the proposal appears, so far at least, to have got lost in the crossfire. It is a policy of huge significance and it deserves to be heard.

Because unlike today's Conservative proposal, which involves the destruction of voluntary sector housing, it has some chance of happening.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on April 14, 2015 02:16

April 13, 2015

The antidote to nationalism: Liberalism

It is now four days since an incredibly bored Daily Telegraph correspondent on the Lib Dem battlebus tweeted in desperation that the bus had just run over a pigeon.

It is now four days since an incredibly bored Daily Telegraph correspondent on the Lib Dem battlebus tweeted in desperation that the bus had just run over a pigeon.It was a dull day on the election front - it usually is (did you understand a word of Ed Balls' interview on the Today programme this morning?) - and the political media fell about laughing, presumably because they believe the Lib Dems are doomed and that this was some kind of omen. I was even commissioned to write about it for the Guardian. You can see what I came up with here.

But the exercise made some things come home to me powerfully. One was what makes this election different from others: this will be remembered as the nationalist general election. It is the election where the real issues have become confused because it isn't clear where the heart of the debate lies.

The truth is, it isn't really about spending commitments or otherwise - which most of the electorate take with a pinch of salt. The central debate is about nationalism, English and Scottish.

This is the case most obviously in Scotland, of course. One of the peculiarities of UK politics is that Liberalism and celtic nationalism often look a bit like each other. They both seem to back local self-determination. I remember my great-aunt (a liberal and a Liberal) saying that the only nationalism that English Liberals have a soft spot for is Irish nationalism.

In fact, the contrast could not be greater. Liberalism is about self-determination at every level, local, regional and personal. For nationalists, it is the nation and only the nation that counts - and that overrides local interests just as it over-rides personal ones. That is why nationalism ends up sooner or later in intolerance.

That is all the more important in England where the intolerance is clearer and where, I have come to believe, that there is some kind of reverse relationship between Lib Dem and Ukip support. It seems clear to me that the Ukip vote is now falling and the Lib Dem vote rising, but so little that this isn't obvious yet. Even so, I predict that Ukip will end up behind in the national vote share as well as seats.

That would then be for me the main message of the campaign, if it was to come about: tolerance and genuine self-determination faces down nationalism. And in Scotland, I have a feeling that only a Lib Dem vote will achieve it.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on April 13, 2015 01:36

April 9, 2015

Iceland, the Greens and the money revolution

The Green Party is a bit of a conundrum. Go to their events and you find a strange division between the articulate, highly effective handful of activists who make things happen and the rest - who tend to be mildly misanthropic, angry types. Perhaps a bit like me.

I have no difficulties at all with their basic premise. It is the overlay of mushy do-gooding kind of unthinking positioning on the left that I find infuriating. It shows little or no thought about the real changes that a greener society would require, especially a society no longer in thrall to economic growth.

They are against student loans, and heavens they may be right - but it isn't a principled stand. It is a thoughtless one. Especially as, behind this unco-ordinated positioning, there seems to be a great deal of equally uncritical rage.

I understand this positioning is designed to attract disaffected Labour and Lib Dem supporters, who would - I would have thought - come to them in even greater numbers if they had genuinely thought through the kind of policies we need. But nobody has.

Consequently, they are blocking progress towards the big shift we need - which will have to attract the conservative right as well as the conservative left if it has any chance of shifting the political world on its axis.

But then, the Greens have at least had the guts to propose a bold Liberal solution: a citizen's basic income of £72 per person, as of right.

This is a traditional Liberal policy, proposed originally by Conservatives working with Beveridge, who saw it as an antidote to the huge bureaucracy of welfare state means-testing. It would set people free from poverty in a dramatic and effective way, and it would slash the corrosive bureaucracy of welfare.

The trouble is that the Greens have not costed it. Nor is it possible to cost. As far as I know, nobody has found a way that such a policy could be even marginally affordable under the current design of money.

When the Social Credit Party of Alberta took control in 1943, their similar basic income proposals were ruled illegal by the Canadian supreme court, since when nobody has even tried. But changes are happening elsewhere which might make this idea more practical.

The Prime Minister of Iceland, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, has commissioned a report proposing a change in the way money is created. At the moment it is created by banks in the form of loans, and inflation is controlled by altering the central bank interest rates. The proposal is that this should change: money would be created interest-free by the central bank instead and issued into circulation - well, that isn't clear, but potentially as a citizens' income.

This is an outline of a far more stable economic system. Its other implications are not clear either, except that it would change domestic banks from money-creators into money-warehousers. It is the proposal put forward in the 1930s by the Chicago School economists, and never enacted.

If Iceland goes ahead - and they might - this could herald one of the big shifts in economics everywhere. If it fails, of course, it will be forgotten. But if it succeeds in creating a more stable economic system that spreads prosperity, other countries will follow suit.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

I have no difficulties at all with their basic premise. It is the overlay of mushy do-gooding kind of unthinking positioning on the left that I find infuriating. It shows little or no thought about the real changes that a greener society would require, especially a society no longer in thrall to economic growth.

They are against student loans, and heavens they may be right - but it isn't a principled stand. It is a thoughtless one. Especially as, behind this unco-ordinated positioning, there seems to be a great deal of equally uncritical rage.

I understand this positioning is designed to attract disaffected Labour and Lib Dem supporters, who would - I would have thought - come to them in even greater numbers if they had genuinely thought through the kind of policies we need. But nobody has.

Consequently, they are blocking progress towards the big shift we need - which will have to attract the conservative right as well as the conservative left if it has any chance of shifting the political world on its axis.

But then, the Greens have at least had the guts to propose a bold Liberal solution: a citizen's basic income of £72 per person, as of right.

This is a traditional Liberal policy, proposed originally by Conservatives working with Beveridge, who saw it as an antidote to the huge bureaucracy of welfare state means-testing. It would set people free from poverty in a dramatic and effective way, and it would slash the corrosive bureaucracy of welfare.

The trouble is that the Greens have not costed it. Nor is it possible to cost. As far as I know, nobody has found a way that such a policy could be even marginally affordable under the current design of money.

When the Social Credit Party of Alberta took control in 1943, their similar basic income proposals were ruled illegal by the Canadian supreme court, since when nobody has even tried. But changes are happening elsewhere which might make this idea more practical.

The Prime Minister of Iceland, Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson, has commissioned a report proposing a change in the way money is created. At the moment it is created by banks in the form of loans, and inflation is controlled by altering the central bank interest rates. The proposal is that this should change: money would be created interest-free by the central bank instead and issued into circulation - well, that isn't clear, but potentially as a citizens' income.

This is an outline of a far more stable economic system. Its other implications are not clear either, except that it would change domestic banks from money-creators into money-warehousers. It is the proposal put forward in the 1930s by the Chicago School economists, and never enacted.

If Iceland goes ahead - and they might - this could herald one of the big shifts in economics everywhere. If it fails, of course, it will be forgotten. But if it succeeds in creating a more stable economic system that spreads prosperity, other countries will follow suit.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on April 09, 2015 02:17

April 8, 2015

The historic destiny of the Lib Dems. There is one.

One of the highlights of the Guardian's election coverage over the weekend was the group of 'blind dates' between opposing politicians they set up - Caroline Lucas with Vince Cable, Danny Alexander with Stella Creasey and so on.

One of the highlights of the Guardian's election coverage over the weekend was the group of 'blind dates' between opposing politicians they set up - Caroline Lucas with Vince Cable, Danny Alexander with Stella Creasey and so on.One of these was an unlikely pairing between Natalie Bennett and the ultra-Tory Jacob Rees-Mogg, and it was here that he was quoted as explaining the basic two categories of Liberal Democrats:

"The Lib Dems have two strains: the classic liberal strain, which is essentially Peelite and quite conservative, and the Social Democrat strain, which is closer to Labour; so they could emphasise one bit of their personality to do a deal with either side..."

I was unnerved by this, not because I'm unaware that people think this, but because - for one awful moment - I thought to myself: maybe he's right.

I recovered my sense of myself, and my sense of the party I belong to, shortly afterwards. But just imagine, if Rees-Mogg was correct.

It would mean that there would be no place for me in the standard bearer for Liberal parties everywhere. I am not a Peelite Conservative and am, in no sense, a social democrat. It would mean there was no place for Liberals either, as I understand them - and other people who recognise that same Liberalism in a straight line from Cobbett, Russell, Gladstone, Lloyd George, Grimond and so on.

It would mean that the ideology that shapes what I believe is no more than an awkward compromise between conservatism and social democracy, both backward-looking creeds, when I see myself as something quite different. Liberalism, it seems to me, is an essentially forward-looking creed.

Nor can we really blame Jacob Rees-Mogg for misunderstanding. If the party has failed to explain where they stand, what their ambitions are beyond coalition, then really it is their own fault. I was on the party's federal policy committee for 12 years - it must be my fault too.

Yet, even in government, it seems to me, the party edged towards a Liberal view of the world whenever they could - apprenticeships, mutualism, green energy investment, local government involvement in health. Perhaps the mistake was in failing to explain how these little shifts fitted into a Liberal approach that went beyond the sum of its parts.

This isn't the right moment to pick over the remains of the coalition years - they may not have finished, after all.

Nor is it really the right time for me to have another go at a future articulation of Liberal economic policy.

But I do think this. Every 40 years, with some accuracy, there is a major shift in economic thinking in practice in the UK. The next one is due in 2020 or thereabouts. The outlines are already clear: it will sweep away the brittle, basically destructive power of finance. It will reshape the economic landscape so that ordinary life can be affordable again, and can stay so. It will end the growing chasm between the tiny elite and everyone else.

The big question is how. It won't happen until all sides agree broadly about how it can be achieved, and I have some ideas myself, and then - when the crisis hits - the political parties are able to shift relatively seamlessly to the new dispensation. History suggests these shifts happen, in the end, quite fast (1979/80, 1940, 1908/09, 1868, 1831 and so on, and so on).

One political party needs to hammer out the basic outlines of the post-Thatcher/Reagan economics in practice. It is the historic destiny of the Lib Dems, it seems to me, that they should play this role. Inside or outside government, that is their task in the next parliament.

Why them? Because deep in the Liberal soul, it seems to me, is an understanding of how economies might work quite differently, and based on an idea that flies in the face of everything we are now taught: that small plus small plus small plus small equals big.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on April 08, 2015 08:58

April 3, 2015

I was wrong three times over about the leaders' debate

Well, I was wrong. I was wrong on many counts.

First, I thought last night’s debate with the seven leaders would be boring but found it was able to cover some issues which would never have been otherwise covered at all – though climate change only got a nod, even from Natalie Bennett. I don’t agree with my friend Nick Tyrone that it was dull – not in comparison with the boring snoring (as they say) prime ministerial grilling by Paxman it wasn’t.

Second, I was wrong that Miliband was recovering his style. I realise this isn’t the way the polls saw it, but I thought he came across as rather creepy, with long lists of policies that seemed incoherent. I thought he got a drubbing on the NHS, and his hand signals seemed embarrassingly masturbatory.

Third, and I’m happy to say this, I was afraid that Clegg’s simplistic positioning as neither one thing nor the other would miss the point – that it would be too anodyne to catch attention. In fact, it suited the occasion very well.

It was delivered with passion and personality. I am, of course, biased, but I thought Clegg managed a kind of effortless dominance over the debate, where Cameron was too tired, Farage was too unpleasant and Miliband was too peculiar.

What I hadn’t realised was that four of the leaders (Miliband, Sturgeon, Wood and Bennett) would simply outline a sort of vague lefty conservatism, a rather woolly condemnation of bad things and demand for good things, and that would make the Clegg formula stand out.

I’ve read the polls. I know this isn’t the popular view, and I have tried to see the events of last night through the eyes of someone who was less committed. I have obviously failed.

But I have a feeling that Nick Clegg managed to build the foundations of a fight back last night that will resonate with people over the coming weeks. That isn’t clear yet. Nor is the sheer creepiness of the leader of the opposition. But my guess is that it will be. We will see.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

First, I thought last night’s debate with the seven leaders would be boring but found it was able to cover some issues which would never have been otherwise covered at all – though climate change only got a nod, even from Natalie Bennett. I don’t agree with my friend Nick Tyrone that it was dull – not in comparison with the boring snoring (as they say) prime ministerial grilling by Paxman it wasn’t.

Second, I was wrong that Miliband was recovering his style. I realise this isn’t the way the polls saw it, but I thought he came across as rather creepy, with long lists of policies that seemed incoherent. I thought he got a drubbing on the NHS, and his hand signals seemed embarrassingly masturbatory.

Third, and I’m happy to say this, I was afraid that Clegg’s simplistic positioning as neither one thing nor the other would miss the point – that it would be too anodyne to catch attention. In fact, it suited the occasion very well.

It was delivered with passion and personality. I am, of course, biased, but I thought Clegg managed a kind of effortless dominance over the debate, where Cameron was too tired, Farage was too unpleasant and Miliband was too peculiar.

What I hadn’t realised was that four of the leaders (Miliband, Sturgeon, Wood and Bennett) would simply outline a sort of vague lefty conservatism, a rather woolly condemnation of bad things and demand for good things, and that would make the Clegg formula stand out.

I’ve read the polls. I know this isn’t the popular view, and I have tried to see the events of last night through the eyes of someone who was less committed. I have obviously failed.

But I have a feeling that Nick Clegg managed to build the foundations of a fight back last night that will resonate with people over the coming weeks. That isn’t clear yet. Nor is the sheer creepiness of the leader of the opposition. But my guess is that it will be. We will see.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on April 03, 2015 04:50

April 2, 2015

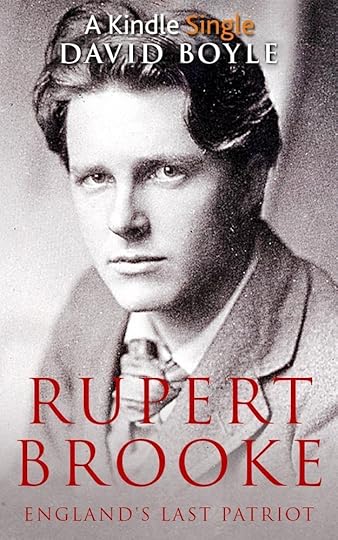

Has upbringing changed since the days of Rupert Brooke?

The election campaign will take all our available attention span over the next few weeks, so I’ve found myself thinking back a century – exactly a century in fact – to the beginning of March 1915. It was then that Rupert Brooke was relaxing with his friends in the Royal Naval Division in Cairo, preparing for the disastrous attack on the Dardanelles.

The election campaign will take all our available attention span over the next few weeks, so I’ve found myself thinking back a century – exactly a century in fact – to the beginning of March 1915. It was then that Rupert Brooke was relaxing with his friends in the Royal Naval Division in Cairo, preparing for the disastrous attack on the Dardanelles.I’ve explained elsewhere how the Dardanelles escapade was a the brainchild of radical Liberals, desperate to avoid what looked like the inevitable carnage on the Western Front, and was stymied in the end by bureaucratic inertia.

The Royal Naval Division, as Churchill’s personal army, was at the forefront of his plans and received the bulk of casualties. Including Brooke, who died hours before the attack, of blood poisoning.

I’ve been thinking about Brooke, who was bitten by the mosquito which killed him later in April while he was in Cairo, and because my short ebook about his last days – Rupert Brooke: England's Last Patriot – was published yesterday (Endeavour Press).

I’ve learned a great deal while I was researching the book, but the main thing which struck me was huge change that hit English society in the early years of the last century.

Thanks partly to the philosophy of G. E. Moore, those born in the 1880s – who bore the brunt of casualties in the First World War – were brought up with a freedom and relaxed lack of interest that dominated the rest of the century.

Rupert Brooke and his friends were the first generation to be allowed to have a group of mixed sex friends to grow up with. We might not be romantic enough for naked bathing these days – still less to enjoy his party piece (which Virginia Woolf witnessed and enjoyed ) of diving naked into the Cam and coming up with an erection – but we recognise the pattern of passionate interlocking friendships, and the freedom to discover them.

But still, that sense of mutual cameraderie – away from parental control, and amidst a pre-Freudian innocence about the titanic feelings that youth can evoke – was something that Brooke and his friends pioneered for the rest of us.

I’m not sure, with all our technologies, that this basic model of upbringing as really changed a century later.

It would be interesting to think about how it might change, and once you think about it, it is kind of obvious how it is changing already. Our children are now considerably more controlled.

They are allowed to rove widely over the internet or approved sets of online games, but they are barely allowed past the end of their own drive – until they go to university. And even then, the economic controls are considerable and so are the mental ones. In fact the two seem to go together.

My own children were not allowed to speak in the corridors in their last primary school. They are not allowed to doodle in their exercise books. They are peculiarly obsessed, like most of their friends, with the intricacies of politically correct speech. I have a feeling, in short, that bringing up children is returning to its pre-Brooke, pre-Victorian roots.

Stands the church clock? Well, up to a point. Find out more in my Rupert Brooke book (it only costs £1.99 and can be downloaded onto a PC or kindle).

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on April 02, 2015 03:10

April 1, 2015

The three contradictions of anti-austerity

[image error]

How does change happen? Because God knows, we need it - and I speak as a supporter of the coalition. Nobody should believe the coalition, ground-breaking as it has been, ought to be the sum total of radical Liberal ambitions. Do they?

I've been asking myself this after a fascinating Guardian Long Read by Giles Tremlett about the rise of the leftist Podemos political movement in Spain, a combination of the New Left circa 1983 and anti-globalisation protest movements, with a dash of Latin American populism.

Podemos is the brainchild of a politics lecturer turned media star, Pablo Iglesias, who has taken his party to the top of the opinion polls. It may turn out to be the model for a resurgent left across Europe, now dominated by the anti-democratic technocrats of the European central bank (Podemos means 'we can').

It rather depends how cross people are. We have no real UK equivalent, unless it is the Greens, who are - in similar ways - radically anti-austerity.

But there are a number of contradictions about the idea that these kinds of movements represent a force capable of driving change.

Contradiction #1 - Anti-austerity is a conservative proposition. Anti-austerity, as currently expressed, implies that the pattern of government spending pre-2010 was some kind of ideal. In fact, it was highly ineffective - pouring money into public services which had ceased to function properly because of the iron cage of targets and outsourcing contracts. If anti-austerity means making sure the poor don't pay for the errors of the rich, then who can be against that? But if it means no cuts to anything, and no major shift in resources in any direction, that is a deeply conservative position to take - and not one that will create the kind of radical change we need.

Contradiction #2 - Real change has to be based on a big idea. Major political and economic shifts happen, in the UK at least, with great regularity every 40 years (we are due for another in 2019/20), and it happens only when there are a set of new defining economic ideas that are available, after considerable debate, whose time has come. It does not happen because of protest or protest movements. People only listen to the protests when there is a practical intellectual proposition behind them. A movement like Podemos remains a protest movement.

Contradiction #3 - Real change has to be based on new political divisions. It is impossible to make change happen when is carried out entirely against the wishes of the majority, unless it is authoritarian in some way. The great mistake the Greens have made here is to fail to find ways of reaching out to a somewhat conservative population. I realise they wanted to appeal to disaffected Liberals and socialists, but they would have got their support anyway - and have by, allowing themselves to be categorised on the left, provided themselves with a rather low glass ceiling.

Podemos also appears to me only to be selling a new kind of protest. It doesn't yet amount to the change we need.

I ask myself rather often now what I can do most effectively to make change happen, because Iglesias is right that the current apotheosis of bankers and banking is wholly corrosive and it would still reek of corruption, even if it was staffed by saints.

What I tell myself is this. The main factor missing for major change to happen is a coherent set of big ideas, which have some potential to provide a good life for the vast majority of people - and to do so more effectively than the current failed raft of tired old policies. So that's where I'm putting my energies.

Though it won't stop me from delivering the occasional Liberal Democrat leaflet in the meantime...

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

I've been asking myself this after a fascinating Guardian Long Read by Giles Tremlett about the rise of the leftist Podemos political movement in Spain, a combination of the New Left circa 1983 and anti-globalisation protest movements, with a dash of Latin American populism.

Podemos is the brainchild of a politics lecturer turned media star, Pablo Iglesias, who has taken his party to the top of the opinion polls. It may turn out to be the model for a resurgent left across Europe, now dominated by the anti-democratic technocrats of the European central bank (Podemos means 'we can').

It rather depends how cross people are. We have no real UK equivalent, unless it is the Greens, who are - in similar ways - radically anti-austerity.

But there are a number of contradictions about the idea that these kinds of movements represent a force capable of driving change.

Contradiction #1 - Anti-austerity is a conservative proposition. Anti-austerity, as currently expressed, implies that the pattern of government spending pre-2010 was some kind of ideal. In fact, it was highly ineffective - pouring money into public services which had ceased to function properly because of the iron cage of targets and outsourcing contracts. If anti-austerity means making sure the poor don't pay for the errors of the rich, then who can be against that? But if it means no cuts to anything, and no major shift in resources in any direction, that is a deeply conservative position to take - and not one that will create the kind of radical change we need.

Contradiction #2 - Real change has to be based on a big idea. Major political and economic shifts happen, in the UK at least, with great regularity every 40 years (we are due for another in 2019/20), and it happens only when there are a set of new defining economic ideas that are available, after considerable debate, whose time has come. It does not happen because of protest or protest movements. People only listen to the protests when there is a practical intellectual proposition behind them. A movement like Podemos remains a protest movement.

Contradiction #3 - Real change has to be based on new political divisions. It is impossible to make change happen when is carried out entirely against the wishes of the majority, unless it is authoritarian in some way. The great mistake the Greens have made here is to fail to find ways of reaching out to a somewhat conservative population. I realise they wanted to appeal to disaffected Liberals and socialists, but they would have got their support anyway - and have by, allowing themselves to be categorised on the left, provided themselves with a rather low glass ceiling.

Podemos also appears to me only to be selling a new kind of protest. It doesn't yet amount to the change we need.

I ask myself rather often now what I can do most effectively to make change happen, because Iglesias is right that the current apotheosis of bankers and banking is wholly corrosive and it would still reek of corruption, even if it was staffed by saints.

What I tell myself is this. The main factor missing for major change to happen is a coherent set of big ideas, which have some potential to provide a good life for the vast majority of people - and to do so more effectively than the current failed raft of tired old policies. So that's where I'm putting my energies.

Though it won't stop me from delivering the occasional Liberal Democrat leaflet in the meantime...

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on April 01, 2015 03:18

March 31, 2015

We need a new Thomas Becket

Back in 2002, I came across an old copy of Hilaire Belloc's book The Old Road. It was being sold off for 40p by my local library, along with many of their other books most worth reading, and I bought it and devoured his journey along the old Pilgrim's Way.

Back in 2002, I came across an old copy of Hilaire Belloc's book The Old Road. It was being sold off for 40p by my local library, along with many of their other books most worth reading, and I bought it and devoured his journey along the old Pilgrim's Way.Reading Belloc changed my outlook on many things. He was a former Liberal MP who left the party and launched one of those Liberal breakaway movements - like the Greens - this one called the Distributist League.

I've written elsewhere about the links between the Liberals and the Distributists, but it is a diversion and a controversial one, so won't do so again now.

The Old Road had been published in 1904, and Belloc described himself setting out from Winchester on old St Thomas Becket Day, 31 December. I realised that if I did the same that year, I was probably leaving exactly a century after Belloc's own journey. And so it was that, on 31 December 2002, bearing umbrellas on a very drizzly day, Sarah and I set off past the ruins of Hyde Abbey and along the flooded route towards the Winchester bypass.

Every few months we would do a little more, eventually with a buggy and a baby, and then with two children. On Palm Sunday, we finally reached the end of the pilgrimage. We were even blessed by a resident chaplain in Canterbury Cathedral.

At the end of the book, Belloc writes:

"In the inn, in the main room of it, I found my companions. A gramophone fitted with a monstrous trumpet roared out American songs, and to this sound the servants of the inn were holding a ball. Chief among them a woman of a dark and vigorous kind danced with an amazing vivacity, to the applause of her peers. With all this happiness we mingled..."

The awkward transition back to modern life, from a medieval dream, which Belloc hints at rather strangely here, I have also now been through. But part of the dream has stayed with me - more than part actually, but this is the relevant bit. It is the meaning of the cult of Thomas Becket, the murdered archbishop, and how much we need something similar now.

Because Becket became a symbol of spiritual resistance to conventional authority. That was the ideal which united all those pilgrims over three and a half centuries. It was a celebration, not just of resistance, but of the possibility of supra-national authority. Or a moral appeal beyond the king and parliament.

It would be too simple to say that this role is covered by the European Convention or the European Union, though they are the flawed successors of the Roman Catholic Church - it is no coincidence that Brussels now plays the same role in the English psyche as Rome once did, irritatingly interfering until we need it.

Becket was not just resisting civilian authority, he was murdered by the king. In these days, the comparison is with Dietrich Bonhoeffer or Oscar Romero, and other spiritual leaders murdered by governments the world over.

You can see why Henry VIII, the great tyrant, was so keen to seize Becket's shrine and how frustrated he must have been that Becket's bones eluded him.

The trouble is, nobody knows where the monks hid Becket's bones, so they elude us too. We need a parallel authority to the state, to support conscience and the possibility of spirituality. The church can aspire to that but it is extremely rusty and very careful, and I remain enough of a modern Liberal to believe it might be stronger if it could unite its voice with the authority of the other faiths which now cover this island (heavens, I'm even intoning like Belloc now...).

Because if there was an annual pilgrimage which underpinned the possibility of moral and spiritual authority, powerful enough to hold the state to account where necessary, then I would set out from Winchester to follow it all over again.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 31, 2015 00:55

March 30, 2015

Why the election 'debate' was so dull

I watched the so-called debate that wasn't a debate with rising incredulity that any two men aspiring to the highest office in the last should be quite so dull and predictable. The only element that was less predictable was Ed Miliband's unexpectedly human smile.

I watched the so-called debate that wasn't a debate with rising incredulity that any two men aspiring to the highest office in the last should be quite so dull and predictable. The only element that was less predictable was Ed Miliband's unexpectedly human smile.I don't know if it was authentic or not, but it came across as such - and I'm sure it lies behind his sudden rise in the polls. But let's face it - it wasn't much.

I've been thinking about the political offering for next month's election and it really is staggeringly uninspiring. Then I read the column in the Financial Times (thanks again, Joe) which talked about a similar disconnect in Washington - the growing gulf between the new thinking of Silicon Valley and precisely the opposite in Washington.

This is how Edward Luce put it:

"Every week, some audacious start-up aims to exploit the commercial potential of science. Many are too zany to succeed. A few will deserve to. Every week, it seems, a presidential campaign is launched. Some of the 2016 candidates are actively hostile to science. None, so far, have hinted at original ideas for fixing America’s problems. One will undeservedly succeed. The root of America’s intellectual disconnect is cultural. In Silicon Valley, “fail harder” is a motto. A history of bankruptcy is proof of business credentials. In Washington, a single miscue can ruin your career..."

We don't have the same extremes in the UK. We don't have fundamentalist anti-science candidates for prime minister. We don't have Silicon Valley mavericks either, except perhaps clustered around Silicon Roundabout and one or two other places.

But the basic division is horribly familiar. It is as if UK politicians regard their failure to propose anything new as a demonstration of their fitness for office. It makes them safer from Paxman of course, but also perhaps insulates them from each other. They are dull enough to be safe. It is the besetting sin of the British political elite.

On the one hand, we have the Conservatives failing to reveal where they are going to save huge sums form the welfare budget, as they say they will. On the other hand, we have Labour wrapping themselves in the NHS, complaining about all those elements - outsourcing, PFI contracts - which they did so much in the 13 years to 2010 to encourage.

On the one hand, we have the English nationalists, on the other hand the Scottish nationalists. Nationalists believe in a thoroughly old idea - nations - and seem to be muddled by the modern world in which the lines between foreigners and everyone else get blurred.

I am biased in favour of the Lib Dems, of course. The pupil premium, the Green Investment Bank and free school meals as a means of socialisation - those are all new ideas, at least for the UK, and ones to be proud of. But they played little part in the last election, which makes me wonder whether the list of those groups of people who really find new thinking pretty irrelevant, and rather inconvenient, should also include political correspondents.

It is the clash of slogans that interests them, and the more familiar the slogans the happier they are.

Nor are the Lib Dems thinking much at the moment, except for the narrowest policy opportunities. Big thoughts are dangerous, but they need not worry - nobody in government has big thoughts any more. There isn't any time to have them.

So there is a dilemma here. The nation needs the Lib Dems in government like never before. But the Lib Dems need a period in opposition if they are going to start thinking again. It is hard to know quite what to wish for most fervently.

Subscribe to this blog on email; send me a message with the word blogsubscribe to dcboyle@gmail.com. When you want to stop, you can email me the word unsubscribe.

Published on March 30, 2015 05:07

David Boyle's Blog

- David Boyle's profile

- 53 followers

David Boyle isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.