Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 21

February 9, 2022

“Think of this movie as a sausage … “

I was in a production meeting at Warner Bros. for the second Steven Seagal movie, Hard to Kill. It was called Seven Year Storm at that time. The director was Bruce Malmuth, a good guy who sadly died way too soon.

Steven Seagal in Hard to Kill

Steven Seagal in Hard to KillThe screenplay had a car chase in it. The movie was low-budget and the sequence was scripted very tightly. Bruce however, lying awake the night before this meeting, had come up with a way to make the chase different and special. But he needed more money from the studio and an extra day of shooting. I remember Bruce rising from his chair and making an impassioned plea for just a few more bucks and a little extra time.

The Warners executive listened calmly with no change of expression. Bruce resumed his seat. He was actually out of breath from making his fervent plea. The exec thanked Bruce for his commitment and his creativity. He saluted him as a dedicated filmmaker and a true artist. Then he said:

“Bruce, think of this movie as a sausage. It’s just another link and you’re grinding it out.”

Everyone around the table, including Bruce, burst into laughter. But we all felt a chill too, at hearing stated in such stark, unvarnished terms the reality of the marketplace.

I remember thinking at the time,

I agree with the executive. This movie IS a sausage. And we ARE grinding it out.

But my attitude toward the grinding, I said to myself, does not have to be cynical or condescending. In fact,

I am grateful as hell to be here working on this sausage and to have a chance to grind it out.

And furthermore …

Nobody, including the studio and the studio executive, can stop me from giving my all to make it the best possible sausage.

In the end I got fired off the picture. You won’t find my name in the credits. But I still agree with what I thought then.

The post “Think of this movie as a sausage … “ first appeared on Steven Pressfield.Every project doesn’t have to be Citizen Kane. It’s okay to work on “B” movies and “C” movies or to write trade ads for Preparation H. As long as we do our absolute best and keep our eyes on the prize of producing, in the end, our own best material, as truly as we can to our own lights.

February 2, 2022

Liz Gilbert’s Deal with Herself

Elizabeth Gilbert is the author of Eat Pray Love and other bestsellers. She’s also a deep and honorable thinker on the subject of the artist and the artist’s soul. When Ms. Gilbert was starting out, she famously declared, she made a deal with her writing.

I will never ask you to support me. I will support you.

Elizabeth Gilbert

Elizabeth Gilbert Let me set that before us again.

I will never ask you to support me. I will support you.

What Ms. Gilbert was declaring for herself and to herself was that if she had to toil as a barista, if she had to drive for Uber, if she had to take a job at Hooters, she would do it.

She would not compromise her writing. She would not sell out her work.

I salute Ms. Gilbert for this declaration 1) because it reflects the hard-core reality of life and the marketplace, and 2) because it preserves her soul and her integrity as a writer.

What was really going on for Ms. Gilbert, as for you and me as well, was that she was caught between two immutable and conflicting realities.

One, she wanted to write what she wanted to write and nothing else.

And two, Nobody wants to read your sh*t.

It was entirely possible, Ms. Gilbert realized (and even highly likely) that if she wrote only what she wanted to write, nobody would want to read it.

Rather than freak out at this possibility, however, Ms. Gilbert took a very brave, very honorable, very hard-core, and very long-range position.

She bet on herself. She bet on her talent, even, I’m sure, when she wasn’t certain that she had any talent. She said to herself:

I’m going to keep doing what I love, writing what I think is the truest work from my soul … betting that sooner or later either I’ll get good enough at it to make people want to read my sh*t … or people’s taste will catch up to mine. In the meantime, I will not tailor my work to the marketplace, I will not sell out to what I imagine will be hot at the box office or topping the New York Times bestseller list. I will find a way to keep body and soul together, whatever sacrifice that may entail, while I pursue my calling as an artist.

Elizabeth Gilbert said to her writing:

The post Liz Gilbert’s Deal with Herself first appeared on Steven Pressfield.I will never ask you to support me. I will support you.

January 26, 2022

Fear of Success Anonymous

This is going to sound like a joke but it’s absolutely true. I once joined Fear of Success Anonymous, aka FOSA. This was in Los Angeles; almost all the group members were actors or screenwriters. The group got so popular it had to disband.

I remember driving home from the final meeting, thinking, “I’ve gotta solve this issue on my own. Fear of Success by definition can never succeed!”

What keeps you and me from finishing a book, a startup, a screenplay? I think it’s tribal. It’s not our fault. It’s in our DNA.

This is what keeps us from finishing our novel. Seriously.

This is what keeps us from finishing our novel. Seriously.Consider the cave man, the foot soldier of the primitive hunting band. (This applies to the cave woman too.) Remember, the tribal era constitutes 99.999% of our evolutionary time as human beings. In the tribe, the greatest terror was expulsion. Getting kicked out of the cave was a death sentence.

What crime would get us expelled from the tribe? Standing out. Being different. This makes sense, right? In a world of fearsome predators, the tribe has to stick together. It can’t afford some crazy guy or gal who’d rather paint cave walls than stand all-night guard against saber-tooth tigers.

That terror of expulsion resides in our bones. It doesn’t matter that we now work at Google and live in a third-floor walkup in Williamsburg. We’re still scared to death of standing out, of being the tall stalk that gets lopped off by the workman’s scythe.

Our novel, our startup, our screenplay … what if it’s REALLY GOOD? What if we ourselves actually possess talent? What if we’re Lady Gaga?

OMG! The tribe kicks us out and we get stomped to death by a woolly mammoth!

Sounds ridiculous, I know, but I swear to God that’s the emotion that flashes across our Unconscious as we tee up the .pdf of the Elizabethan family saga we’ve labored on for four years and our finger pauses over the SEND key.

How do we do it? How do we overcome our terror of finishing, how do we beat our Fear of Success?

The answer, again, can be nothing other than Will. Somehow we have to teach ourselves to jam our eyes shut, suck in a deep breath, and jump off the cliff.

The post Fear of Success Anonymous first appeared on Steven Pressfield.January 19, 2022

Finishing, #2

My first agent was a gentleman named Barthold Fles. He was seventy-six; I was twenty-nine. One day over coffee Bart asked me, “How much is 427 minus one?”

I gave the obvious answer: 426.

“No,” said Bart. “It’s zero.”

He was speaking about pages in a novel.

427 minus one = zero

427 minus one = zeroIf the full book is 427 and you’ve written 426, you haven’t got 426/427ths.

You’ve got nothing.

Bart didn’t need to say any more. I went home and got back to work.

The post Finishing, #2 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.January 12, 2022

“It’s very well typed”

It took me seven years to finish my first book. (I wrote about this in The War of Art.) I couldn’t sell it. Couldn’t find a buyer. In fact it would be twenty-one more years before a novel of mine actually saw the light of publication.

But finishing that first manuscript meant everything. Was it any good? I was renting a little cottage in Northern California then and my landords, a couple, had watched me slave and agonize through two years to finish the book. They were curious. They asked to read it. When they returned the manuscript a week later, their comment was, “It’s very well typed,”

I didn’t care. My demons were about finishing. Until then, I had gotten to the 99-yard line on every project and compulsively blown them all up. I couldn’t get to THE END. I couldn’t ship, to use Seth Godin’s perfect term.

How do you get through a barrier like that? It’s Resistance, yes. You can tell yourself that. You can identify the monster. But how do you slay it? How can you finish, when every cell in your body is screaming, QUIT QUIT QUIT?

The only answer I’ve found is sheer will. There’s a legend about Michael Crichton (Jurassic Park, The Andromeda Strain, many more) that as he got close to the end on a novel he was writing, he would start getting up earlier and earlier in the morning to work on it. First it was six o’clock, then five, then four. Finally he’d have to move out of the house, check into a hotel, just to keep from driving his wife crazy.

Michael Crichton was smart. He knew that as he approached the moment of truth, of shipping, of exposing his creation to the world, his inner Resistance would ramp up its intensity, trying to sabotage him, to keep him from reaching THE END.

So he upped his own intensity. I didn’t know Michael Crichton, but I can imagine his self-talk during those final do-or-die weeks. No doubt he lashed himself like a Marine drill instructor. He encouraged himself like a highly-paid coach.

Finish it. Don’t chicken out! FINISH THE DAMN THING!

In other words, will. Pure, no-nonsense will.

For me, the agony of not finishing something … the shame, the self-loathing, the disgrace in my own eyes and the eyes of everyone who knew me … was like a fiery goad that seared my flesh every morning.

“It’s very well typed.”

I don’t care! The thing is done! It’s a wrap! I did it. Nothing anyone can say or think, even if they’re 1000% right, can take that away from me.

And here’s the even better news (which proved true for me and which I pass on to all of us struggling to get a make-or-break project across the finish line):

Once you finish, even one time, you will never have trouble finishing again.

The post “It’s very well typed” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.January 5, 2022

Gen. Slim Gets it Together, Part Two

We left General Slim last week contemplating the string of catastrophic defeats his Allied forces had suffered at the hands of their enemy in Burma and India.

The strength of the Japanese lay … in the spirit of the individual Japanese soldier. He fought and marched till he died. If five hundred Japanese were ordered to hold a position, we had to kill four hundred and ninety-five before it was ours—and then the last five killed themselves. It was this combination of obedience and ferocity that made the Japanese Army, whatever its condition, so formidable.

Worse, Slim’s own troops were reeling emotionally.

Jungle fighting was not like the movies

Jungle fighting was not like the moviesNothing is easier in jungle fighting than for a man to shirk. If he has no stomach for advancing, all he has to do is flop into the undergrowth; in retreat, he can slink out of the rearguard, join up later, and swear he was the last to leave. A patrol leader can take his men a mile into the jungle, hide there, and return with any report he fancies. Only discipline—not punishment—can stop that sort of thing; the real discipline that a man holds to because it is a refusal to betray his comrades.

You and I as writers and artists also face an implacable enemy—the force of fear, self-doubt, and self-sabotage inside our own heads. How do we produce a countervailing force?

Morale is a state of mind. It is that intangible force which will move men to give their last ounce to achieve something, without counting the cost to themselves; that makes them feel they are part of something greater than themselves … I remember sitting in my office and tabulating these foundations of morale something like this:

1. There must be a great and noble object.

2. Its achievement must be vital.

3. The method of achievement must be active, aggressive.

4. The [individual soldier] must feel that what he is and what he does matters directly toward the attainment of the objective.

General Slim started with small-unit patrolling and ambushes. He sought successes for his troops to build their self-confidence.

We had now to extend this confidence to [larger] units and formations. [More ambitious attacks] were carefully staged, ably led, and, as I was always careful to ensure, in greatly preponderating strength. We attacked Japanese company positions with brigades fully supported by artillery and aircraft … [we assaulted] platoon posts by battalions. Once when I was studying the plan for an operation … a visiting staff officer of high rank said, “Isn’t that using a steam hammer to crack a walnut?” “Well,” I answered, “if you happen to have a steam hammer and you don’t mind if there’s nothing left of the walnut, it’s not a bad way to crack it.” At this stage [of the beaten army recovering its self-confidence], we could not risk even small failures.

I love too the characteristics that General Slim sought when he conceived of, or approved, an action against the enemy.

The principles on which I planned all operations were:

1. The ultimate intention must be an offensive one.

2. The main idea must be simple.

3. That idea must be held in view throughout and everything else must give way to it.

4. The plan must have in it an element of surprise.

These principles are not bad either for planning a book or a movie or any kind of artistic or entrepreneurial venture. And they worked.

The Arakan battle, judged by the size of the forces engaged, was not of great magnitude, but it was, nevertheless, one of the historic successes of British arms. It was the turning point of the Burma campaign. For the first time a British force had met, held, and decisively defeated a major Japanese attack, and followed this up by driving the enemy out of the strongest possible natural positions that they had been preparing for months and were determined to hold at all costs.

Within eighteen months, General Slim’s forces, despite their “forgotten theater” handicap of lack of supplies, weapons, and logistical support, were closing in on an even greater prize.

One of the gunners, stripped to the waist, was slamming shells into the breech of a twenty-five pounder [howitzer]. I stepped into the gun pit beside him. “I’m sorry,” I said, “you’ve got to do this all on half rations.” He looked up at me from under his battered bush hat. “Don’t you worry about that, sir. Put us on quarter rations, but give us the ammo and we’ll get you into Rangoon!”

Thank you, General Slim. You’ve just given us the mindset for our next novel, screenplay, art installation, dance, hip-hop album, Thai Fusion restaurant, tech startup, and run for political office.

The post Gen. Slim Gets it Together, Part Two first appeared on Steven Pressfield.December 29, 2021

Gen. Slim Gets it Together

I’m reading a book I love but that I would not recommend to anyone unless they’re as crazy as I am. The book is dense. Reading it is like hacking a trail through elephant grass. But every page has some powerful insight for us writers and artists if we’ve got the patience to stick with it.

The book is Defeat Into Victory by Field Marshal Viscount William Slim. Ever heard of him? Nobody else has either. But he was one of the great fighting commanders of WWII. He was the British general who defeated the Japanese in Burma and India, after the fall of Manila and Rangoon, the Bataan Death March, and the defeat of virtually every Allied force in Southeast Asia.

A few [of the retreating British] managed to cross [the Sittang River] with their arms on rough rafts or petrol tins. Numbers were drowned; some were shot while crossing. By the afternoon of the 24th, all that had reached the west bank out of eight battalions … was under two thousand officers and men, with 550 rifles, 10 Bren guns, and twelve Tommy guns between them. Almost all were without boots, and most were reduced to their underwear.

Field Marshal Viscount William Slim

Field Marshal Viscount William SlimOur Writing Wednesdays post last week was about self-reflection. General Slim’s book is that principle put into action.

This was not the first, nor was it to be the last, time that I had taken over a situation that was not going too well. I knew the feeling of unease that comes first at such times, a sinking of the heart as the gloomy facts crowd in; then the glow of exhilaration as the brain grapples with problem after problem; lastly the tingling of the nerves and the lightening of the spirit, as the urge to get out and tackle the job takes hold. Experience had taught me, however, that before rushing into action it is advisable to get quite clearly fixed in mind what the object of it all is. I sat down to think out what our object should be.

You and I in our artistic endeavors have known defeat. Some of us live with it year after year. We know the way forward is inside us. But how do we access it?

I had now an opportunity to sit down and think about what had happened. We had taken a thorough beating. We, the Allies, had been outmanoeuvred, outfought, outgeneraled … To our men, the jungle was a strange, fearsome place; moving and fighting in it was a nightmare. To the Japanese, it was a welcome means of concealment and surprise. Tactically we had been completely outclassed. The Japanese could—and did—do many things that we could not.

In a Hollywood movie, the images we’d see would be bombs exploding and soldiers charging with fixed bayonets. But the true image (for you and me as well as for General Slim) was of a solitary individual—and in fact the only one in all the Allied forces—sitting down alone and thinking.

The only test of generalship is success, and I had succeeded in nothing I had attempted. Time and again I had tried to pass to the offensive and every time I had seen my house of cards fall down… we had been worsted, and we had paid the penalty—defeat. Defeat is bitter. Bitter to the common soldier, but trebly bitter to his general … He will remember the soldiers he sent into the attack that failed and who did not come back. He will recall the look in the eyes of the men who trusted him. “I have failed them,” he will say to himself, “and failed my country!” He will see himself for what he is—a defeated general. In a dark hour he will turn in upon himself and question the very foundations of his leadership and his manhood.

And then he must stop! He must shake off those regrets and stamp on them, as they claw at his will and his self-confidence. He must beat off those attacks he delivers upon himself, and cast out the doubts born of failure. Forget them, and remember only the lessons to be learnt from defeat—they are more than from victory.

I love books like Defeat Into Victory because they open a window into the mind—and mindset—of a solitary individual, no different from you and me, who faced incredible adversity and somehow overcame it.

More next week about exactly what General Slim did to turn the tide.

The post Gen. Slim Gets it Together first appeared on Steven Pressfield.December 22, 2021

The Lost Art of Reflection

You would think that I as a writer should know this and use it. But it took two friends—Joe Byerly and Ryan Holiday—to open my mind to this practice.

Reflection.

Or, more accurately, self-reflection.

Bearded dude reflecting

Bearded dude reflectingJoe Byerly has a new book out (with Cassie Crosby) called My Green Notebook. Highly recommended, by the way. The “green notebook” is literally a notebook that the army gives to its young officers. (As an enlisted man, I never heard of it.) Its purpose is to jot down “lessons learned.”

Sounds really dumb, doesn’t it? But if you try it, it’s amazing how helpful the practice can be.

The Stoics exercised reflection daily, according to Ryan Holiday. Read Marcus Aurelius. Or Seneca or Zeno or Epictetus.

The idea is at the end of the day to take a few minutes, preferably with pen and paper or laptop, and ask yourself, “What did I learn today?”

Just as an example from my own demented psyche, I’ve been involved lately in an unwanted dispute. As I was driving on the highway a couple of days ago, I realized that despite all the unpleasantness, I really had no ill will toward the person I’ve been clashing with. I held nothing against him. I saw our disagreement as no one’s fault—just a consequence of differing needs and points of view. I could definitely get past it. I could go forward with a clean slate.

This was a revelation to me. I had no idea I felt that way. I thought, “I should write Person X and tell him that I hope we can put this kerfuffle behind us and go forward in a positive frame of mind.”

As writers and artists, you and I will have more professional reflections as well.

“Chapter Six is too long. Go back and cut it.”

“Great name for a character—Fred Knipsia.” (I’m stealing this from my friend Norm Stahl.).

The act of reflecting is not like meditation. It’s more like conscious self-assessment. But there’s an element of self-surrender in it too. You have to “sit back” and let the buried stuff rise to the surface.

I realized taking up this practice that there was one area in which I’ve been doing something similar for years.

Dreams.

I’m a huge believer in recording and interpreting (if you can) the dreams and even nightmares that come to you in sleep.

Oddly enough—or perhaps not so oddly—I had a corresponding dream to the revelation above, just two nights later.

Bottom line: I highly recommend this Stoic/Green Notebook practice. It’s like a sailor or a wilderness trekker taking their navigational bearings at the end of the day.

You realize where you are. It helps.

The post The Lost Art of Reflection first appeared on Steven Pressfield.December 15, 2021

Save 50% when you …

I know I promised last week to continue our examination of Michael Shaara’s Killer Angels, but instead I must interrupt this message with a word from our sponsor …

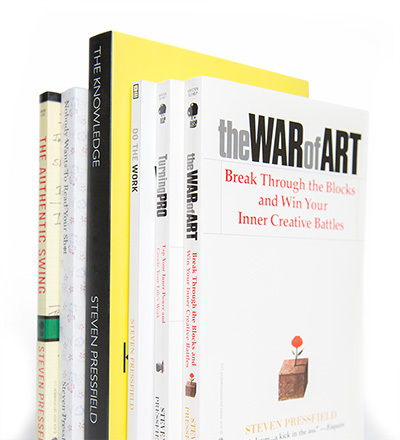

A couple of books are missing from this pic, but you get the idea …

A couple of books are missing from this pic, but you get the idea …Are you aware of www.blackirishbooks.com? It’s the online bookstore for The War of Art, Turning Pro, etc.

I mention this as Christmas approaches because you can get the “author’s discount” of 50% on any order of ten books or more.

What made me think of this was yesterday I was signing an order of 40 War of Arts for Bo Eason, who’s a friend and a coach who runs mastermind groups. Bo regularly gives out signed copies of The War of Art to his mastermind clients. Because he lives in the next town, he just orders the books in bulk, I sign them, then he picks them up in person.

But we can do this via mail or UPS/Fedex too.

This offer applies to any book of mine that Black Irish publishes—The War of Art, Turning Pro, The Warrior Ethos, Do the Work, Nobody Wants to Read Your Sh*t, The Artist’s Journey, the Authentic Swing, or The Knowledge.

If you’d like me to sign copies, write me at steve@stevenpressfield.com and we’ll figure out shipping and make a plan.

Or if you’d just like the books at a 50% discount, simply place your order on www.blackirishbooks.com.

The 50% discount is automatically applied on all orders over ten copies.

Sorry, you can’t “mix and match.”

The post Save 50% when you … first appeared on Steven Pressfield.December 8, 2021

Lessons from “The Killer Angels”

Forgive me, every once in a while I can’t stop myself from delivering a post purely about narrative technique.

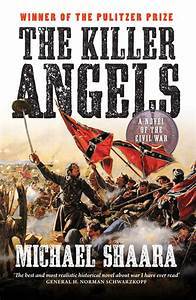

Michael Shaara’s “The Killer Angels” won the Pulitzer in 1975

Michael Shaara’s “The Killer Angels” won the Pulitzer in 1975I’ve been reading Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels—fiction (but very, very real) about the battle of Gettysburg. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and it deserved to. Here are a couple of observations on the subject of “How the hell did he do that?”—just between us chickens.

How does Michael Shaara deliver to the reader the massive amount of information about topography and time, troop movements, strategic planning, weather, alterations and overthrows of fortune, within the incredibly complex tale of the battle? This question, I’m certain, was not resolved by accident or whim. Shaara thought it through deeply and arrived at his solution. What was that solution?

Much of what dramatists call “exposition”—i.e. straight information that the reader needs to know if she is going to understand the story—is delivered not by some Omniscient Author or objective third-party narrator, but through dialogue between the principal characters.

Lee bent toward the map. The mountains rose like a rounded wall between them and the Union Army. There was one gap east of Chambersburg and beyond that all the roads came together, weblike, at a small town. Lee put his finger on the map.

“What town is that?”

Longstreet looked. “Gettysburg,” he said.

And though virtually all the “speaking parts” are of generals—Lee, Longstreet, Ewell, A.P. Hill, Pickett, Chamberlain (so that we get almost no verbal clues from sergeants or privates or troops on the field)—the action still feels absolutely grounded to the grimy reality of front-line warfare. This is because Michael Shaara keeps his point of view at ground level. When exchanges take place between the principal actors, the reader is with them on the roads, behind the stone walls, sharing coffee beside a mess tent, climbing the heights under fire.

The staff had moved back. The two generals were alone. Longstreet said, “Sir, my two divisions, Hood and McLaws, lost almost half their strength yesterday. Do you expect me to attack again the same high ground which they could not take yesterday, at full strength?”

Lee was expressionless. The eyes were black and still.

Longstreet said, “Sir, there are now three Union corps on those rocky hills, on our flank. If I move my people forward, we’ll have no flank at all; [the enemy will] simply swing around and crush us. There are thirty thousand men on those heights. [Union] cavalry is moving out on my flank now. If I move Hood and McLaws, the whole rear of this army is open.

“General,” Longstreet said slowly, “it is my considered opinion that a frontal assault here would be a disaster.”

Shaara uses another technique available only to writers of fiction. He takes us, the readers, inside the heads of his principals.

Longstreet got down from his horse. He was very, very tired.

There is one thing you can do. You can resign now. You can refuse to lead [the attack.]

But I cannot do even that. Cannot leave the man [General Robert E. Lee] alone. Cannot leave because I disagree, because, as he says, it’s all in the hands of God. But they will mostly all die. We will lose it here. Even if [our troops] get to the hill, what will they have left, all ammunition gone, our best men gone? And the thing is, I cannot even refuse. I cannot leave him to fight it alone; they’re my people, my boys. God help me, I can’t even quit.

More on this subject next week.

The post Lessons from “The Killer Angels” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.