Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 22

December 1, 2021

Training = Turning pro

Amateurs have amateur habits. Pros have professional habits.

How does the pro acquire professional habits?

By training.

(The amateur by contrast either trains like an amateur or doesn’t train at all.)

The passage below comes from Rosanne Cash’s wonderful 2011 memoir, Composed.

Rosanne Cash, post-training

Rosanne Cash, post-trainingFrom that moment I changed the way I approached songwriting, I changed how I sang, I changed my work ethic, and I changed my life. I sought out Marge Rivingston in New York to work on my voice and I started training, as if I were a runner, in both technique and stamina. I started paying attention to everything, both in the studio and out. If I found myself drifting off into daydreams–an old, entrenched habit–I pulled myself awake and back into the present moment. Instead of toying with ideas, I examined them, and I tested the authenticity of my instincts musically. I stretched my attention span consciously. I read books on writing by Natalie Goldberg and Carolyn Heilbrun and began to self-edit and refine more. I went deeper into every process involved with writing and musicianship. I realized I had earlier been working only within my known range–never pushing far outside the comfort zone to take any real risks. I started painting, so I could learn about the absence of words and sound, and why I needed them. I took painting lessons from Sharon Orr, who had a series of classes at a studio called Art and Soul.

There’s a word for the changes Rosanne incorporated into her life.

Training.

And another one: Turning pro.

I remained completely humbled by the dream [that had precipitated these external changes] and it stayed with me through every waking hour of completing King’s Record Shop … I vowed the next record would reflect my new commitment. Rodney [Crowell, Rosanne’s then-husband] was at the top of his game as a record producer, but I had come to feel curiously like a neophyte in the studio after the dream. Everything seemed new, frightening, and tremendously exciting. I had awakened from the morphine sleep of success into the life of an artist.

When we take ourselves and our artistic aspirations seriously, we resolve to move from working like an amateur to working like a pro.

We ask ourselves, “How can I get better? What do I have to do to become a worthy vessel for my gift? How can I elevate myself from where I am now to the higher, truer, more realized artist I know I can be?”

There’s a word for that answer.

It starts with a “T.”

The post Training = Turning pro first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 24, 2021

Training = Self-training

We were talking last week about the writer or artist’s need for training.

You and I are no different from athletes or warriors. We do what we do in the face of an opposing force.

Call it Resistance, call it self-sabotage, call it demons of self-destruction. This force is as real as a headwind or a contrary current is to a triathlete or an armed foe on the battlefield is to a soldier.

The athlete or the soldier has an advantage over you and me, however. They can work with a coach. They have a sergeant or a lieutenant to hold their feet to the fire. They can literally be TRAINED by a professional. Some pro athletes have entire retinues of coaches and training professionals.

Some athletes have entire retinues of coaches and trainers

Some athletes have entire retinues of coaches and trainersYou and I are alone.

We can’t train. We have to self-train.

I break it down into three areas in my own work.

Self-motivation.

Self-validation.

Self-reinforcement.

And I add another:

Self-preparation, meaning my interior rehearsals for various emergencies.

What form does this self-training take?

It’s talk. Self-talk. It’s interior conversations between me and myself.

An example: I’m in a situation right now where, for reasons I can’t talk about, I’m not able to publish stuff I’ve already written. I’ve got two books done and ready to go. But I can’t do anything with them.

Here’s my self-talk addressing this situation (which covers all four of the categories above):

Steve, an external event (just like an ambush in war or a setback in an athletic event) has broken your normal rhythm of production. The temptation now is to slack off. The voice of Resistance in your head will tell you to “take it easy” or “explore new possibilities.” You will feel like, “Hey, I’ve done my bit, let me back off for a minute until we can get back on track with our normal work rhythm.”

In other words, I’m saying to myself what a professional coach or trainer would say to me if I had one.

What you must do now, Steve, is the opposite of what Resistance wants you to do. You must raise your intensity. Pick the next project and plunge in with the same level of concentration and aspiration (or higher) as if there had been no external interruption. Block that out. The enemy now, as always, is Resistance..

Instead of slacking off, even a little, increase your level of exertion. Put your head down and work. Self-reinforce every day. Self-validate every day. Self-motivate every day.

Things now are NOT normal. They are harder. They are an insidious form of emergency. Treat this moment that way.

That’s training. That’s self-training.

The post Training = Self-training first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 17, 2021

The Willing Embrace of Training

We were talking a couple of weeks ago about the artist’s or warrior’s “willing embrace of chaos.”

There’s another, far less glamorous item that the artist or warrior embraces.

Training.

There’s an axiom in every army in the world.

“In an emergency you don’t rise to the occasion, you sink to the level of your training.”

“We sink to the level of our training.’

“We sink to the level of our training.’Soldiers train, athletes train. Why? Because they know that under game pressure or the surprise and dislocation of an emergency, the mind goes into a freeze or a fog. Training is to embed a conditioned response to this state, one that doesn’t require cognitive thinking. “Run to the sound of the guns.” “Drop and return fire.” “Get out of the house!”

Sailors practice “Man overboard!” drills, families rehearse earthquake drills. Even in elementary school (sad, sad to say), kids and teachers practice active-shooter drills.

You and I as writers face an emergency enemy too. Its name is Resistance. Resistance says, “You had a great day of work yesterday, let’s slack off today.” Or “This new idea of yours is a loser. Let’s drop it.”

In Act Two, we hit walls. Close to the finish, we experience panic. When it comes time to take our work to market, we freak, we freeze, we run for cover.

In an emergency we don’t rise to the occasion, we sink to the level of our training.

There’s only one answer for you and me, or for any solitary artist or entrepreneur.

Training.

We must rehearse and reinforce ourselves every day to respond to these emergencies without haste and without panic. The firefighter knows that walls will unexpectedly crash and floors will give way beneath him; the triathlete knows her bike chain will snap out of nowhere or her hamstring will seize up two miles from the finish line.

To prepare for these exigencies, they train. They rehearse. They prepare mentally.

You and I are athletes and firefighters too. It’s not glamorous or cinematic to prepare mentally for the hour when two years of work unspools into nothing. But it’s professional. It’s the game. It’s the life we’ve chosen.

“Run to the sound of the guns.” “Drop and return fire.” “Get out of the house!”

The post The Willing Embrace of Training first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 10, 2021

In Praise of Mothers

We’ve talked often in these posts about the Warrior Mindset as a template for the writer or artist or entrepreneur’s inner world. Treat the struggle as a war. Fight it like a warrior.

But there’s another paradigm, another archetype that may be even more powerful.

I’m talking about the Mother.

When you think about it, the writer or artist is more like a mother than a warrior.

First, she is doing that which only God Himself and other artists have done. She is bringing forth onto the material plane a living being that has never existed before.

The artist’s work is the Mother’s baby. She conceives it, she carries it to term, she gives birth to it.

Now consider the Mother once her issue has been brought into the world. In many ways, she is more ferocious in its cause than a warrior.

A mother will run into a burning building to save her child.

A 110-pound mom will lift a Buick with her bare hands to protect her baby.

A mother will kill for her child. She will sacrifice anything, even her own life, in defense of her offspring.

A mother will give up her own vanity (no small thing) in favor of raising her child. Fashion? Weight? Hair, nails, skin? In the tradeoff of time—for herself or for her child—a mom will show up uncombed, un-made-up, in yoga pants and flip-flops to register her kid for pre-K or to root her child on in soccer.

More amazing than these, a mother will emancipate her child from her own vanity of expectations. Does she wish her daughter would graduate from Stanford and become a professor of French Literature? She’ll release her to become a professional wrestler. And never lose a jot of love or commitment.

You and I have to be like that mother.

We are here to serve, not our own selves or our own ambition, but the new life that will be born through us.

We must protect that life. We are its vessel. That which we perform for ourselves is in service only of that new life.

Nor can we cling to or possess that new life. We are only the medium through which it has entered the world. We must not force it or manipulate it into being what we want it to be. We must let it be what it is and what it will become.

We must release it. We must let it go.

This is nature. This is life. This is our role.

We are warriors. And we are mothers.

The post In Praise of Mothers first appeared on Steven Pressfield.November 3, 2021

The Willing Embrace of Chaos

I gave a talk a few weeks ago at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana. The title of the talk was “The Warrior Mindset.”

(Whenever you see the term “warrior” in something written by me, insert/replace it with “writer” or “artist.” In my mind, they’re the same thing.)

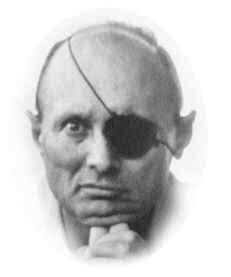

In the talk, I cited this passage from the great Israeli general Moshe Dayan. It comes from his 1967 book, Diary of the Sinai Campaign:

Moshe Dayan

Moshe DayanTo the commander of an Israeli unit, I can point on a map to the Suez Canal and say: “There’s your target and this is your axis of advance. Don’t signal me during the fighting for more men, arms, or vehicles. All that we could allocate you’ve already got, and there isn’t more. Keep signaling your advances. You must reach Suez in forty-eight hours.” I can give this kind of order to commanders of our units because I know they are ready to assume such tasks and are capable of carrying them out.

In Hebrew, the word for chaos is balagan. (It’s actually part-Russian, part-Hebrew.) Its usage goes something like this:

“What was it like, jumping out of that airplane in a thunderstorm?”

“It was a complete balagan!”

Warriors, athletes, stand-up comedians, moms pushing strollers, cops, firemen … they all know that their day can be plunged at any moment into chaos. (Moms perhaps most of all.)

They learn to incorporate this awareness into their mindset.

Some come to live for this chaos. It’s the most fertile and exciting part of their day.

You and I as writers and artists must learn to embrace chaos as well.

Chaos is a product of Resistance.

Chaos will hit us in Act Two. It’ll hit us at the finish of our novel, our dance, our documentary film.

Chaos = fear. Chaos = mental disorientation. Chaos = confusion.

Can we function in this state? Like that Israeli officer, can we keep pushing forward even when we’re out of touch with higher command and have lost contact with friendly units on all sides? Can we maintain our focus? Can we keep our confidence?

The poet John Keats gave this skill a name. He called it “negative capability.”

… at once it struck me what quality went to form a Man of Achievement, especially in Literature, and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason …

Embarking on a new work of fiction or nonfiction, a new startup, a new enterprise of any kind, you and I need to prepare ourselves mentally for periods of chaos. We need to be able to feel our flight suit become drenched with sweat, our own terror-sweat … and still keep flying the plane.

We need to be able function in the midst of a balagan.

The post The Willing Embrace of Chaos first appeared on Steven Pressfield.October 27, 2021

The Pain Zone

John Naber won four swimming gold medals at the ’76 Olympic Games in Montreal, each in world-record time. He said something in an interview once that sticks with me to this day.

John Naber, deep in the Pain Zone

A reporter asked Naber, “What’s the difference between a good swimmer and a great swimmer?”

Here’s how Naber answered (I’m paraphrasing from memory):

The thing about competitive swimming is that the instant you hit the water, you enter the Pain Zone. Your heart is hammering, your lungs are on fire, your muscles are straining to their maximum. It’s hell.

The difference between a good swimmer and a great swimmer is that the great swimmer has the capacity to go a little bit deeper into the Pain Zone … and to stay there a little bit longer.

I’m just now finishing a novel—filling the blank pages on the climactic chapters—and I am deep into the Pain Zone. Resistance is kicking my ass. I think of John Naber every day.

Gloria Steinem once said

I don’t like to write. I like to have written.

It helps me a lot to remind myself first that there is a Pain Zone, and second, that it’s universal. Every one of us hits that wall. Every one feels our lungs burning, our heart about to explode out of our chest. Every one of us wants to quit. Every one wants to back off, just a little, so this damn struggle will stop hurting so much.

I keep thinking back to John Naber.

The post The Pain Zone first appeared on Steven Pressfield.The difference between a good swimmer and a great swimmer is that the great swimmer finds a way to go a little bit deeper into the Pain Zone … and to stay there a little bit longer.

October 20, 2021

“I wasn’t even operational”

Do you know the word “operational?”

I didn’t.

It’s a military term, used in armed forces all over the world.

It means “certified for combat.” It means they give you the keys to the plane or the tank or the aircraft carrier. You have passed the test. You’re cleared hot.

I was interviewing Zvi “Kantor” Kanor, a pilot who at age seventeen got called out of flight school to fly combat missions in the Six Day War.

“It was crazy. I wasn’t even operational!”

Other pilots have described harrowing action in the sky.

“This happened on my first mission. I was barely operational!”

Here’s a true story from Afghanistan. My friend Major Jim Gant of the Special Forces wrote a book called One Tribe at a Time. It was a white paper, laying out a different type of strategy—what came to be called a Tribal Engagement Strategy—for fighting the war in that overwhelmingly tribal country. General David Petraeus was in charge of all US and Coalition forces in Afghanistan at the time. He read Major Gant’s paper and thought it made a lot of sense.

Major Jim Gant (right) in a tribal shura, Kunar province, Afghanistan

Major Jim Gant (right) in a tribal shura, Kunar province, AfghanistanThe story is that General Petraues called his staff together and, dropping the paper on the table before them, declared, “Operationalize this.”

{Full disclosure, there was no happy ending for the Tribal Engagement strategy.]

The point is the word.

Operational.

“Officially certified to participate in a military operation.”

Or operationalize.

“To make operational. To make ready for ‘live’ or ‘kinetic’ action.”

Are you and I operational? Are we cleared, even if only in our own minds, to fly or trek or sail into combat, even if that combat is only against our own Resistance and the problems of our work?

If we’re Charles Dickens, are we ready to wrangle Pip and Fagin and Mr. Micawber? If we’re Jon Krakauer, are we ready to leap Into Thin Air? If we’re Elizabeth Gilbert, have we got the guts to Eat Pray Love?

In a way, our writer’s type of combat is harder than the kind faced by military men and women. It’s harder because nobody certifies us. There’s no flight school or boot camp or BUDS training for us. Nobody mentors us or validates us. Nobody pins a Trident or an SF tab or an Eagle, Globe, and Anchor on the breast of our tunic.

We have to train ourselves. We have to test ourselves. We have to validate and commend and reinforce ourselves.

And even when we are truly operational, nobody issues us orders or points us toward the enemy, let alone honors our efforts or recognizes our contributions or even evaluates and takes note of them.

We have to declare ourselves operational, then find the operation to enlist our energies in. Then we have to do all that must be done within that operation. And after that, when we come home (if, in fact, we do make it home) our task is to recognize ourselves and validate our efforts and rally our intensity to do it all again, when all too often no one beyond our immediate family knows or notices or cares.

That’s operational, brothers and sisters!

The post “I wasn’t even operational” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.October 13, 2021

Sweating Through Your Flight Suit

Here is a scene I heard over and over, interviewing Israeli fighter pilots (and I’m sure it’s commonplace in air forces and other combat units all over the world.)

A pilot would describe returning to base after a combat mission. He’d land safely, taxi to a stop; his ground crew would come running to the plane; they’d set the ladder against the aircraft’s flank, open the the cockpit cowling so the pilot could climb out and down … only he, the returning fighter pilot, would be so wrung out emotionally and so shattered with fatigue that he couldn’t get out of his seat.

Ground crewmen would have to literally lift him from under the arms and carry him down to terra firma.

A Mirage IIIC cockpit. Sometimes a pilot didn’t have the strength to get out.

A Mirage IIIC cockpit. Sometimes a pilot didn’t have the strength to get out.And yet …

And yet, he, the pilot, had completed the mission. He had dropped his bombs, he had fought off enemy attacks in the air, he had done what he was sent out to do.

In such a situation [here is Gen. Ran Ronen on the subject], the pilot’s body will exhibit all the manifestations of fear. His heart rate will soar; his flight suit will become drenched with sweat. But his mind must remain focused. His thinking must stay clear and calm.

I know it’s a stretch to compare what you and I do—safe in our offices with our cups of tea or coffee beside us—with the peril faced by pilots in life-and-death air-to-air combat. But there is, at least metaphorically, a parallel.

You and I deal with panic too. We feel our lives flash before our eyes. Our hearts race, our blood pressure soars, our figurative flight suits become soaked with sweat.

The lesson here is that doesn’t matter. That’s just the body doing what bodies do.

It’s okay to feel terror. It’s okay to break down in tears (as I myself have done countless times). It’s okay to finish the day so weak and limp, you have to pour yourself out of your chair and collapse into the arms of the nearest spouse/wet bar/loyal Labrador.

It’s okay to feel and do all that.

Just keep flying the mission.

The post Sweating Through Your Flight Suit first appeared on Steven Pressfield.October 6, 2021

When panic strikes …

Can you stand another Fighter Pilot Wisdom post?

Let’s start with another moment from our friend, fighter ace Giora Romm. Flying in the north of Israel on Day Two of the Six Day War, Giora’s Mirage IIIC got hit by an enemy missile. Here’s Giora describing his situation:

The plane was for the moment still airworthy but I knew I had to get on the ground fast. The nearest landing strip was about twenty kilometers south. I turned toward it and lowered my landing gear. But the missile had hit the Mirage’s undercarriage, right beneath my seat. Had the landing gear in fact lowered? I had no way to know. The indicator on the instrument panel had been knocked out by the missile strike.

Mirage IIIC cockpit. Sometimes even your instruments can’t save you.

Mirage IIIC cockpit. Sometimes even your instruments can’t save you.What did Giora do?

It was late afternoon. The sun was low in the sky. I descended to near ground level and banked so that I could see my plane’s shadow on the ground.

Yes, the landing gear were down.

Another pilot from Giora’s squadron, Arnon Levushin, ran out of fuel on his first solo training flight. He could see the emergency landing field in the distance. He turned toward it. But did he have enough speed and altitude to reach the runway? No control tower could tell him. No gauges or instruments could make the call.

I lined up my pipper (the gunsight on the plane’s windscreen) with the forward edge of the runway. I figured as long as the targeting “X” stayed above the horizon line, my glide path was good. But if the pipper dropped below the apron of the runway, that meant I would not make it … and I’d have to start looking for a farmer’s field to crash-land in.

(Yes, Levushin made it.)

I love these stories because they inspire us all to use our noodles, as my mother would’ve said.

What clever solutions!

What simple, straightforward answers!

And how great that in moments of potential panic and paralysis, these fliers were able to keep their heads and come up with such smart and unorthodox solutions.

The post When panic strikes … first appeared on Steven Pressfield.September 29, 2021

“Just write the damn thing!”

Let’s get back to our “fighter pilot wisdom” series.

Flashing back to our friend, Israel Air Force ace (for shooting down five enemy planes) Giora Romm, let me paraphrase something he told me about fighter pilots in general.

There are some pilots in any squadron who are excellent fliers, undoubtedly brave in many air-to-air contexts, yet who in action will often loiter around the margins of an engagement rather than plunging aggressively into the fray. I witnessed this a number of times in confrontations with the enemy along the border. This is in wartime, remember. Certain pilots would stay on our side of the line and not cross over.

Wow. I had never thought of that. But hearing Giora tell it, I could believe that was a common phenomenon.

Air-to-air combat. Who’s who? What’s what?

Air-to-air combat. Who’s who? What’s what?It got me asking myself what the equivalent was in the writer’s world. I realized I had an answer, at least for me, immediately to hand—and on the very book I was interviewing Giora for.

When I got back from Israel after conducting interviews for The Lion’s Gate, I had almost five hundred hours of tape from about eighty interviewees—soldiers, tankers, and airmen who had fought in the Six Day War of 1967.

I took this responsibility very seriously. This was not fiction, where I could make stuff up or change the story to suit my own aims. This was real. I had to be absolutely true to what had factually happened.

I began transcribing the interviews. Each one took about a week. I was scrupulous. I was religious. I was painstaking.

I was loitering.

The realization hit me one day. There’s the enemy. There’s the engagement. And here I am, hanging back, flying in circles on the wrong side of the border.

I said to myself, “Just write the damn thing!”

Immediately all problems cleared up.

Resistance takes many forms, and one of them is the temptation to loiter around the margins of our book, our movie, our startup.

Giora, in our interview, went on to make a further point.

I don’t believe these pilots’ problem was lack of courage. The issue was that they were unsure of the contours of the problem. Planes were zooming this way and that. Who’s who? What’s going on? The pilots were hanging back, as if they were waiting for a photo to develop. Whereas other pilots (like me) were comfortable jumping in, even when we weren’t sure exactly what was going on. That’s airmanship—the ability to make a judgment based on minimal cues, sometimes even totally insufficient ones.

I was like those hanging-back pilots at that point in writing The Lion’s Gate. I peered at the work before me, and all I saw was confusion. I kept waiting for the picture to come into focus. But it never did. I could’ve spent a year transcribing interviews and been just as uncertain as I was at the start.

Sometimes you have to fly straight into the chaos.

Sometimes you have to tell yourself, “Just write the damn thing!”

The post “Just write the damn thing!” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.