Steven Pressfield's Blog, page 23

September 22, 2021

Abrahams on the carpet

Here’s another “hand over your badge and your gun” moment, but without a badge or a gun. It comes from the movie Chariots of Fire, which won the Oscar for Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay in 1981.

I cite this to illustrate the “hero’s journey” beat in so many novels and movies, in which the hero is stripped of his institutional approval, in whatever form that may take, and must make the choice to continue his journey entirely on his own hook.

To set the stage:

Harold Abrahams (Chariots of Fire is a true story, by the way, and Abrahams a true historical character) is a Cambridge undergraduate slated to run in the hundred-meter dash at the 1924 Olympics. He’s also a Jew, experiencing all the subtle and not-so-subtle prejudices we might imagine in that era in an institution that represents the centuries-old soul of the English class system.

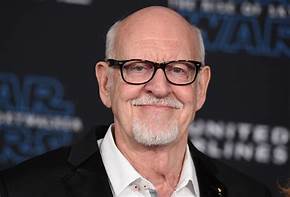

Ben Cross as Harold Abrahams in “Chariots of Fire”

Ben Cross as Harold Abrahams in “Chariots of Fire”In one scene, Abrahams is summoned to dinner with the Master of his college at Cambridge (Caius College, pronounced “keys”) played by Lindsay Anderson and the Master of Trinity College, played by Sir John Gielgud—both at their stuffy Old English best. Abrahams himself is played by Ben Cross. The three men meet in the Masters’ Rooms, a book-lined Gothic setting radiating history and tradition. All are attired formally.

Why has Abrahams been called on the carpet? It takes a few minutes before the two Masters get to the point.

TRINITY

Abrahams, I’m afraid there is a growing suspicion

in the bosom of the University that in your enthusiasm

to succeed, you have, perhaps, lost sight of [Cambridge’s

loftiest traditions.]

ABRAHAMS

May I ask what form this disloyalty takes?

CAIUS

It’s been said you use a personal coach.

HAROLD

Mr. Mussabini, yes.

CAIUS

Do I take it that you employ Mr. Mussabini on a

professional basis?

HAROLD

Sam Mussabini is the finest, most advanced, clearest

thinking athletics coach in the country. I am honored

that he considers me worthy of his complete attention.

CAIUS

Nevertheless, he’s a professional.

HAROLD

What else would he be, he’s the best!

TRINITY

Ah, well there, Mr. Abrahams, I’m afraid our paths

diverge. The University believes that the way of the

amateur can produce the most gratifying results.

HAROLD

I am an amateur!

TRINITY

(suddenly vitriolic)

You are trained by a professional. You have adopted a

professional attitude. For the past year you have

concentrated wholly on developing your own technique,

in the headlong pursuit, may I suggest, of individual glory.

HAROLD

I am a Cambridge man first and last. I am an Englishman

first and last. What I have achieved, what I intend to achieve,

is for my family, my university, and my country, and I

bitterly resent your suggesting otherwise.

CAIUS

My boy, your approach has been, shall we say, a little

too plebeian. You are the elite, and, as such, must be seen

to run rather to the manner born.

HAROLD

Would you prefer I played the amateur — and lost?

CAIUS

To playing the tradesman? Yes!

Abrahams regards the two Dons—petrified, as they are, in a bygone age. He stands. He extends his hand to Caius.

HAROLD

Thank you, sir! The evening has been most illuminating.

(to Trinity)

And good-night to you, sir!

Abrahams starts toward the door, then turns and faces back.

HAROLD

You know, gentlemen, you yearn for victory just as I do.

But achieved with the apparent effortlessness of gods.

Yours are the archaic values of the Prep School play-

ground. You deceive no one but yourselves. I believe

in the relentless pursuit of excellence — and I shall

carry the future with me!!

Caius and Trinity watch Abrahams exit. Trinity turns to Caius.

TRINITY

There goes your Semite, Hugh. A different God.

A different mountaintop.

See how Abrahams has been called on the carpet and ordered to “hand over his badge and his gun”?

Prior to this scene, Abrahams had trained and competed believing he did so with the blessing of his college and his university. He felt like a fully-vetted Englishman competing under the banner of his beloved native land.

By the time he exits this evening, however (even though he did not hear the “Semite/mountaintop” comment), Abrahams feels that the scales have fallen from his eyes. He realizes that he will never be accepted, at least not by the deeply conservative masters of his universe, as a true Englishman and member of the elect. He will always be, by one definition or another, “the tradesman.”

In hero’s journey terms, the stakes have gone way up in this scene. Abrahams’ inclusion among the elite has been jerked out from under him, exactly like a police detective being forced to hand over his badge and his gun. From here on, Abrahams realizes, it is him (and Sam Mussabini) against the world.

Our hero has been forced to make a choice. Does he cave or does he dig in and fight?

It seems that this beat, or a moment very much like it, is necessary in any hero’s journey story. How much, the hero must answer, do I really want my objective? What price am I willing to pay? For us as storytellers, that price must be as high as possible. The higher the price, the better the story.

P.S. Abrahams (in the movie and in real life) goes on to win the gold medal in the Olympics. The filmmakers give us a brief scene in which the Master of Trinity College is informed of this. Sir John Gielgud delivers his line with supreme aplomb.

SERVANT

He did it, sir! Abrahams. He won!

TRINITY

As I always knew he would.

Chariots of Fire was conceived by David Puttnam, written as a screenplay by Colin Welland, and directed by Hugh Hudson. Its producers were Jake Eberts, Dodi Fayed and David Puttnam.

The post Abrahams on the carpet first appeared on Steven Pressfield.September 15, 2021

“And the Bad Version is … “

This comes via my friend Charlie Daly, who got it from a screenwriter friend of his.

It’s a trick to get your writing going when you’re stuck.

Charlie and his bride Dominique on their recent wedding day

Charlie and his bride Dominique on their recent wedding dayCharlie’s friend will sit down at his laptop, set his fingers on the keys and tell himself, “And the bad version is … “

Then he’ll start typing.

I realized, when Charlie told me this, that I’ve been using this sneaky bit of business myself for thirty years. I just never had the nomenclature.

The Bad Version. We can all do that, right?

By telling ourselves that we’re only writing the Bad Version, we take the pressure off. Our sentences don’t have to be brilliant. Our dialogue can be lame. We’re free to lose complete track of theme, narrative, everything.

It’s all okay because our aim is only to write the Bad Version.

And later, when we read over our Bad Version, we’re free to cut ourselves some slack for its quality. So it’s bad? That’s what we said it would be!

The other great thing about writing the Bad Version is when we’re done, we’ve got a version. It might be bad, but it’s something. We can build on that something. We can rewrite. We can reconfigure. We can reconstitute.

And the best part? Sometimes, in the middle of pounding out the Bad Version, we stumble onto a run of phrases or snatches of dialogue that we can later steal when we go back and craft the Bad Version into the Good Version.

Thanks, Charlie! And thanks to your “bad” friend from Tinseltown.

The post “And the Bad Version is … “ first appeared on Steven Pressfield.September 8, 2021

“Your badge and your gun”

We were working on the script for the first Steven Seagal movie, Above the Law. The director, Andy Davis, said, “We need a scene where Steve is ordered to turn in his badge and his gun.”

I remember thinking, “Really? Hasn’t that same moment been in every detective movie since silent pictures?”

I was wrong.

Richard Madden (he was Robb Stark in “Game of Thrones”) in Netflix’ “The Bodyguard”

Richard Madden (he was Robb Stark in “Game of Thrones”) in Netflix’ “The Bodyguard”We wrote it and it worked. Last night I was watching the British series, The Bodyguard (which is really good) on Netflix. Sure enough, they had a “Turn in your badge and your gun” scene. It worked too. The Silence of the Lambs, same thing, this time with Jodie Foster. In The French Connection, Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) is pulled off the case. This same scene gets included by top-shelf writers and filmmakers over and over. Why?

I began thinking about this metaphorically. What does “your badge and your gun” really mean?

It means our hero has been stripped of his or her societal authority. In the Navy, they tear off your petty officer’s stripes. In the Special Forces, they take your tab. At Harvard, they revoke your tenure.

This moment, it seems, is a mandatory station-stop on the hero’s journey. It’s a convention of many, many genres.

What this beat means for the hero is that he or she must decide, “Will I continue my quest (to solve the crime, to save the damsel, to redeem myself) even though society has revoked my official authority and I am now totally on my own?”

In fact, the hero’s jeopardy is even worse because now she or he has been forbidden under penalty of law/expulsion/sanction from pursuing that (honorable) course.

With this moment and the choice that has been thrust upon the hero, the story’s stakes have gone way up. The price the hero must pay has been elevated dramatically.

In the audience, we love it because we get to see what the hero is made of. If he or she were to back off at this moment, we would hurl tomatoes at the screen. We want our protagonist to be all-in, hell or high water, do or die.

In other words, some version of the “Turn in your badge and your gun” moment is a necessary beat across multiple genres. It’s in Westerns, it’s in love stories, it’s in apocalyptic thrillers.

Whatever story I’m working on, I must ask myself, “Do I have a Badge and Gun scene of some kind … and if not, why not?”

There’s no doubt in my mind that some version of this scene must be in there.

The trick is to write it in some new way, with some innovative twist.

The post “Your badge and your gun” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.September 1, 2021

Elevating the Threshold of Panic

Picking up from last week’s post in our series on Fighter Pilot Wisdom, here’s more from fighter ace Ran Ronen:

Why do we train? To perfect our flying skills, yes. But far more important, we practice to elevate our threshold of emotional detachment, to inculcate that state of preparedness and equilibrium that enables a pilot to function effectively under conditions of peril, urgency, and confusion.

If you or I were to hitch a ride in the backseat of a contemporary fighter jet, I’m betting our heart rate would hit 200 bpm before our pilot had completed the first barrel roll. And speaking purely for myself, by the time we had entered the Mach 1.3 power dive straight toward the deck, one of us would definitely be peeing in his pants.

The Mirage IIIC as flown by Ran Ronen and Giora Romm

The Mirage IIIC as flown by Ran Ronen and Giora RommYet our pilot, male or female, would not have broken a sweat. Why? Is she superhuman? Is her courage DNA that far superior to ours? Here’s fighter ace Giora Romm describing part of the training regimen under his squadrom commander, Ran Ronen.

At the end of each training day, the squadron met in the briefing room. Ran stood up front. He went over every mistake we had made that day—not just those of the young pilots, but his own as well. He was fearless in his self-criticism, and he made us speak up with equal candor. If you had screwed up, you admitted it and took your medicine. Ego meant nothing, Improvement was everything.

You and I, in the bowels of a year-long or two-year-long solitary creative project, will strike Panic Point after Panic Point. Resistance will hammer us. We will be tempted over and over to freak out, to pull the plug, to self-destruct, to quit.

What will keep us going is training. Self-training in our case because we don’t have a squadron commander to help us.

On our own, we must train to elevate our threshold of panic. The pilot who flew us on our imaginary joy ride stayed calm because she had executed those same aerobatic maneuvers five hundred, a thousand times before. Each time her threshold of emotional detachment got a little higher. Each time she stayed cooler. Each time the action became more everyday.

Being a pro in any field means more than mastering technique. It means managing one’s emotions in times of extreme and unexpected stress. There’s no training manual for this.

Can we do it? Can we practice? Can we rehearse? Can we process our mistakes and learn?

Can we move up, mentally, from the backseat of the jet to the front?

The post Elevating the Threshold of Panic first appeared on Steven Pressfield.August 25, 2021

The Mission like a movie

Continuing our series on Fighter Pilot Wisdom, here is Ran Ronen, one of the most celebrated combat fliers and commanders (he died in 2016 as a retired brigadier general) in the history of the Israel Air Force.

Preparing for these missions, I would hole myself up in the operations bunker and go over every detail of the coming flight. This is not like studying for exams. You are running the mission like a movie through your mind, anticipating every possible emergency, then planning and mentally rehearsing your response.

Ran Ronen in 1973

Ran Ronen in 1973But preparation was more, Ran continued, than rehearsing for predictable exigencies.

A fighter pilot accelerating down the runway on an operational mission must keep foremost in his mind one reality: at some point before his wheels touch down again, something is certain to go wrong. Will he have an engine failure? Will an unseen enemy appear? Will another plane in his formation experience a crisis of some kind? Bank on it: Something unexpected will happen. When it does, it will be followed almost always by a second emergency, and often a third, in immediate succession, each one producing a graver crisis than the one before. In such a situation, the pilot’s body will exhibit all the manifestations of fear. His heart rate will soar; his flight suit will become drenched with sweat. But his mind must remain focused. His thinking must stay clear and calm.

You and I, embarking on a two- or three-year creative or entrepreneurial project, can count on the same thing happening. Unexpected Emergency #1 will materialize, followed immediately by our own Panicked Reaction #1, which in turn produces Unexpected Emergency #2, leading inevitably to Freaked-out Overreaction #2.

Can we stay calm in the midst of crisis? Can we keep thinking clearly and working at our optimum level?

I’m in the midst of a similar situation right now. An external event with super-negative twists and turns is afflicting me emotionally every day, even pursuing me into my dreams at night. Indeed I am freaking out. Indeed my daylight hours are full of crazed phone calls and emergency consultations.

But one thing remains inviolable. I will not stop working on the book I’m writing now. And I will not stop working to my fullest capacity.

That’s the mission, and I will keep flying it no matter what.

And here’s the weird part. In some crazy way, I think the book I’m working on is actually coming out better.

I keep this wisdom from Ran Ronen before me 24/7. It helps.

The post The Mission like a movie first appeared on Steven Pressfield.August 18, 2021

“Dvekut baMesima”

When I was doing research in Israel for The Lion’s Gate, I spent hours and hours interviewing fighter pilots. I had never known any before; I had no conception of their unique and super-specific mindset, the way they were trained to think and to prepare for life-and-death missions in the sky. I was amazed. I found these airmen’s way of thinking not only fascinating but extremely applicable to the way you and I work as writers and artists.

I’m going to take the next few weeks on this blog to explore some of the parallels.

Giora Romm in his Mirage IIIC

Giora Romm in his Mirage IIICOne point before we begin. The aviators I interviewed flew during the period around the Six Day War, i.e. the late 60s. Their world was old school. No computers. No satellites. No “fire and forget” missiles.

Air-to-air combat in their day was man-against-man, Red Baron, get-your-enemy-in-your-gunsights-and-shoot-him-down-before-he-shoots-you flying. In other words, a perfect parallel for what you and I do against the foes inside our own heads.

Let’s start this investigation with a passage from Giora Romm, who as a twenty-two-year-old lieutenant became the first fighter ace [shooting down five enemy planes] in the history of the Israel Air Force. The following comes from one of his interviews in The Lion’s Gate:

When I was fifteen, I applied for and was accepted into a new military boarding school associated with the Reali School in Haifa. The Reali School was the elite high school in Israel. The military school was a secondary school version of West Point. We attended classes at Reali in the morning and underwent our military training in the afternoon.

I don’t believe there is an institution in Israel today that can measure up to the standards of that school. Why did I want to go there? I wanted to test myself. At that time in Israel the ideal to which an individual aspired was inclusion as part of a “serving elite.” The best of the best were not motivated by money or fame. Their aim was to serve the nation, to sacrifice their lives if necessary. At the military boarding school, it was assumed that every graduate would volunteer for a fighting unit, the more elite the better. We studied, we played sports, we trekked. We hiked all over Israel. We were unbelievably strong physically. But what was even more powerful were the principles that the school hammered into our skulls.

First: Complete the mission.

The phrase in Hebrew is Dvekut baMesima.

Mesima is “mission”; dvekut means “glued to.” The mission is everything. At all costs, it must be carried through to completion. I remember running up the Snake Trail at Masada one summer at 110 degrees Fahrenheit with two of my classmates. Each of us would sooner have died than be the first to call, “Hey, slow down!”

When I first started writing, I could never complete anything. I would get to the finish line and choke. I’d quit. I’d blow the project up.

It took me years to face down these demons of self-destruction.

I wish I had known then Giora’s principle of dvekut ba mesima. I certainly think about it now before I start any new book, article, creative project, anything.

I set my mind at the start just the way Giora would before taking off in his Mirage IIIC or his F-4 Phantom.

Mesima is the mission.

Dvekut is” glued to.”

The post “Dvekut baMesima” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

The mission is everything.

At all costs it must be carried through to completion.

August 11, 2021

Write the Big Moment Big

I have a friend who runs a successful literary agency in Los Angeles. She represents screenwriters. I asked her once, “Is there any single mistake your writers make, not in business or marketing, but in the writing itself?”

She replied without hesitation,

“When they come to the Big Scene, they chicken out.”

I asked her to elaborate.

“Think about the ‘She’s my sister, she’s my daughter’ scene in Chinatown. Or the moment in The Godfather when Michael says, ‘If Clemenza can figure a way to have a weapon planted for me … then I’ll kill them both.” Those are Big Moments. Both are central to their dramas. And in each one, the writers and directors held nothing back. They didn’t under-write. They didn’t underplay. And both those moments are immortal.”

The filmmakers didn’t underplay this moment in “Chinatown”

The filmmakers didn’t underplay this moment in “Chinatown”My friend said that her writers (and by extension, of course, all of us) tend to be risk-averse in their stories’ Big Moments.

“Partly it’s because they’ve been told that subtext is more powerful than text. Or they’re afraid that if they go balls-out for emotion and the moment doesn’t work, they’ll look foolish. So they deliberately under-write. They back off from having Carmela scream at Tony, ‘I was in love with Furio!’ Or from Tony slamming his fist through the wall two inches from Carmela’s face.”

My friend said she routinely has to force her writers to revisit their Big Moments and be brave enough to take the risk of really going for it.

I confess when I heard that, my blood ran a little cold.

I thought, “Am I doing that?”

Of course I am. And for the same reasons my friend cited.

The post Write the Big Moment Big first appeared on Steven Pressfield.

Memo to self: Don’t chicken out next time.

Write the Big Moment Big.

August 4, 2021

Coco Chanel’s advice for writers

Coco Chanel was asked once, “What’s the single piece of fashion advice you would give to ladies (and gentlemen)?”

The grand dame of Parisian couture replied:

On your way out the door, stop and look in the mirror. Then take one thing off.

We as writers could do a lot worse than to heed Coco’s advice.

What paragraph, what chapter, what section would our book be stronger without?

Sometimes Coco didn’t follow her own rule

Sometimes Coco didn’t follow her own ruleA Hollywood producer I respect once told me,

“There never was a script that didn’t get better with ten percent cut.”

She added:

The post Coco Chanel’s advice for writers first appeared on Steven Pressfield.“And when you’ve cut ten percent, cut ten percent of THAT.”

July 28, 2021

Put Your Ass Where Your Heart Wants to Be, #2

My friend Frank Oz has a term for this. He calls it “going the distance.”

It’s an inner test Frank applies at the start of any project, not just to himself but to anyone he will prospectively collaborate with—on a movie, a play, whatever. He asks himself, “Is this person someone who will give it their all, who will commit unconditionally to this work and this alliance? Is this someone who is capable of digging deep, of going to the core of the material, no matter how much it hurts?”

Can you and I pass Frank’s test?

Can you and I pass Frank’s test?This is, to me, the second-level meaning of “Put your ass where your heart wants to be.”

We talked last week of the physical dimension.

Sit your body down in front of the keyboard.

Transplant your physical person to the city where your dream is most likely to find its home soil.

But the second level of this axiom is about the inner body. It means “move to the Paris in your mind.”

Depth of commitment.

That locus within your soul where your dream resides … can you move your will and your intention and your love to that metropolis? If we could take a Google Earth photo of your inner world, would we find your cat and your dog and your family parked there—at the epicenter of the dream?

When a movie director like Frank Oz takes on a project, he’s like you and me at the start of a novel. He’s projecting a two- or three-year commitment. He knows that at some point during that passage, the wheels of the project will come off. A crisis will present itself at which the faint of heart will pull the ripcord and bail. That’s when Frank’s term “go the distance” comes in.

He wants men and women on his movie-making team who will hang in, no matter what. Because that’s the only way great work gets done.

But Frank doesn’t only mean, “Stay when the going gets tough.” He means, “Burrow deep. Work at depth. Dig to the heart of the project and don’t fade when the material resists.”

“How much do you want it?”

“What price are you willing to pay to make this thing succeed?”

“Have you moved—lock, stock, and barrel—to your inner Paris?”

The post Put Your Ass Where Your Heart Wants to Be, #2 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.July 21, 2021

Put Your Ass Where Your Heart Wants to Be, #1

Let’s start with the most obvious interpretation of this axiom. (We’ll go deeper in succeeding weeks.)

What do we mean by “ass?”

In this first-level expression, the word means body. Our physical being.

When we say “put your ass where your heart wants to be,” we mean station your physical body in the spot where your dream-work will happen.

Do you want to write? Sit down at the keyboard.

Wanna paint? Step up before the easel.

Dance? Get your butt into the rehearsal studio.

Sometimes people will write to me. “I want to work in the movies. Do I have to move to Los Angeles?” Or, “My dream job is in fashion design. Do I need to be in Manhattan?”

The answer is yes and yes.

Hemingway moved to Paris. Joni Mitchell made a home in Laurel Canyon. Andy Warhol grabbed his bags and took off for New York.

Andy Warhol followed his dream from Pittsburgh to Manhattan

Andy Warhol followed his dream from Pittsburgh to ManhattanSomething wonderful happens when we pack up and execute a pilgrimage to the place where our heart’s true action lies. The universe notices. The Muse approves.

But even more important, we move our physical body into proximity with other like-minded souls—our peers, our mentors, our fellow aspirants–who are making or have already made the same bold move. Hemingway gets to hang with Gertrude Stein and Lady Duff Twysden, who became Brett Ashley in The Sun Also Rises. Henry Miller finds himself talking all night in cabarets with Anais Nin and Blaise Cendrars. And Glenn Frey gets to chill with J.D. Souther and Jackson Browne, not to mention Linda Ronstadt and Don Henley.

None of this creative ferment would’ve happened if these artists-in-embryo had not set sail on a steamer or hopped aboard a Greyhound.

It’s not enough for your heart to be in the right place. Your physical body needs to be there too.

The post Put Your Ass Where Your Heart Wants to Be, #1 first appeared on Steven Pressfield.