Lessons from “The Killer Angels”

Forgive me, every once in a while I can’t stop myself from delivering a post purely about narrative technique.

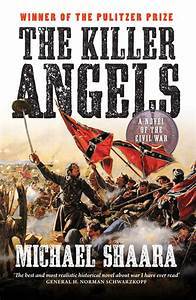

Michael Shaara’s “The Killer Angels” won the Pulitzer in 1975

Michael Shaara’s “The Killer Angels” won the Pulitzer in 1975I’ve been reading Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels—fiction (but very, very real) about the battle of Gettysburg. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and it deserved to. Here are a couple of observations on the subject of “How the hell did he do that?”—just between us chickens.

How does Michael Shaara deliver to the reader the massive amount of information about topography and time, troop movements, strategic planning, weather, alterations and overthrows of fortune, within the incredibly complex tale of the battle? This question, I’m certain, was not resolved by accident or whim. Shaara thought it through deeply and arrived at his solution. What was that solution?

Much of what dramatists call “exposition”—i.e. straight information that the reader needs to know if she is going to understand the story—is delivered not by some Omniscient Author or objective third-party narrator, but through dialogue between the principal characters.

Lee bent toward the map. The mountains rose like a rounded wall between them and the Union Army. There was one gap east of Chambersburg and beyond that all the roads came together, weblike, at a small town. Lee put his finger on the map.

“What town is that?”

Longstreet looked. “Gettysburg,” he said.

And though virtually all the “speaking parts” are of generals—Lee, Longstreet, Ewell, A.P. Hill, Pickett, Chamberlain (so that we get almost no verbal clues from sergeants or privates or troops on the field)—the action still feels absolutely grounded to the grimy reality of front-line warfare. This is because Michael Shaara keeps his point of view at ground level. When exchanges take place between the principal actors, the reader is with them on the roads, behind the stone walls, sharing coffee beside a mess tent, climbing the heights under fire.

The staff had moved back. The two generals were alone. Longstreet said, “Sir, my two divisions, Hood and McLaws, lost almost half their strength yesterday. Do you expect me to attack again the same high ground which they could not take yesterday, at full strength?”

Lee was expressionless. The eyes were black and still.

Longstreet said, “Sir, there are now three Union corps on those rocky hills, on our flank. If I move my people forward, we’ll have no flank at all; [the enemy will] simply swing around and crush us. There are thirty thousand men on those heights. [Union] cavalry is moving out on my flank now. If I move Hood and McLaws, the whole rear of this army is open.

“General,” Longstreet said slowly, “it is my considered opinion that a frontal assault here would be a disaster.”

Shaara uses another technique available only to writers of fiction. He takes us, the readers, inside the heads of his principals.

Longstreet got down from his horse. He was very, very tired.

There is one thing you can do. You can resign now. You can refuse to lead [the attack.]

But I cannot do even that. Cannot leave the man [General Robert E. Lee] alone. Cannot leave because I disagree, because, as he says, it’s all in the hands of God. But they will mostly all die. We will lose it here. Even if [our troops] get to the hill, what will they have left, all ammunition gone, our best men gone? And the thing is, I cannot even refuse. I cannot leave him to fight it alone; they’re my people, my boys. God help me, I can’t even quit.

More on this subject next week.

The post Lessons from “The Killer Angels” first appeared on Steven Pressfield.