Justin Taylor's Blog, page 194

August 29, 2012

Three New Trinitarian Books

Not only are there three new, practical, introductory books on the Trinity now available, but two of them have the same name!

Fred Sanders reviews Tim Chester’s Delighting in the Trinity: Why Father, Son, and Spirit Are Good News.

Mike McKinley recommends Sam Allberry’s Connected: Living in Light of the Trinity.

And Carl Trueman recommends Mike Reeves’ Delighting in the Trinity: An Introduction to the Christian Faith.

It’s a joy to see good authors with pastoral impulses writing practical books on the center of our faith. May their tribe increase!

A Message That Might Save Your Marriage

Russell Moore’s talk—which you can listen to here or watch below—could be used by God to keep many of us from making shipwreck of our marriages and our faith. It’s a sobering word, but a word in season, on maintaining moral purity in our marriages.

You can watch or listen to more messages from their marriage conference here.

August 28, 2012

Do Not Muzzle the Ox: Does Paul Quote Moses Out of Context?

“You shall not muzzle an ox when it is treading out the grain” (Deut. 25:4).

This command, which appears only once in the Old Testament, would garner little attention except for the fact that the apostle Paul cites it not once but twice (1 Cor. 9:9; 1 Tim. 5:18), making apostolic application to his right to be supported financially as a minister of the gospel. And he does so in such a way that it makes it sound like he is bypassing what the command was originally about.

Moses (serving as the covenant mediator for Yahweh) seems compassionately concerned about the oxen getting enough to eat, getting their fair share when working hard.

Paul, on the other hand, seems to say that God isn’t primarily concerned about oxen. In 1 Corinthians 9:9-10 he asks rhetorically:

Is it for oxen that God is concerned? [The Greek wording implies an emphatic "No!"]

Does he [=Moses] not certainly speak for our sake?

This raises lots of questions, like:

Is Paul saying that Moses never meant this to be applied to literal oxen?

Is he merely referring to the ultimate intention of the passage?

Is he focusing on contemporary application rather than original meaning?

Is he quoting this verse out of context?

We can answer questions like this by going back to the text and asking some questions of our own.

Are There Issues with the Original Text and Grammar?

There are no disputed textual or grammatical issues at play in this Deuteronomy 25:4. A good literal translation would be: “do not muzzle an ox in its threshing.” (“Out/of the grain” is added in many English translations for clarification; Paul himself adds it to his quotation for the same reason.) Contra the NET Bible, there is no specification of the owner of the ox; in other words, there is no indication of possession (e.g., “your ox” or “his ox”). Whether the ox is owned or borrowed by the recipient of this command must be determined from context (both textually and historically) and logic. In my opinion, this is a more significant consideration than it appears at first glance.

What Did It Originally Mean?

The terseness of the command means that the motivation, the ground, and the application must all be inferred.

The surface issue is that of muzzling. If an ox wears a muzzle during the process of tramping the grain on the threshing floor, then it cannot eat the grain. Yahweh through Moses is saying that this is wrong. But the reason is not specified.

Virtually all interpreters have recognized the upshot: if an ox is without muzzle, then it can partake of the fruit of its own labor, and this is regarded as a good thing. But many interpreters stop at this point and fail to press in more deeply.

Who Is the Command Really For?

One question that commentators rarely ask or answer is this: Is it the owner of the ox, or it is someone who is renting or borrowing it? And what is the motivation behind the command? Is the primary issue Yahweh’s compassion and protection for animals (cf. Prov. 12:10; Jonah 4:11), or is there an element of human justice and protection at play (cf. Deut. 22:14)?

There are two basic options for the identity of the man to whom this command is directed: he is either (1) the owner of the ox, or (2) someone borrowing or renting the ox. Each option could then be subdivided based on the location of the threshing: the owner of the ox could be (1a) threshing his own grain, or (1b) threshing someone else’s grain; likewise, the borrower/renter could be (2a) threshing his own grain, or (2b) threshing someone else’s grain. Schematically we could represent the possible logical options as follows:

Owner of Ox

Renter/Borrower of Ox

Own grain

1a

2a

Someone else’s grain

1b

2b

There is nothing in the Hebrew grammar to answer these questions for us. All four options are perfectly compatible with the terminology and structure of this short command.

The option of a man renting or borrowing an ox to thresh someone else’s grain, while possible, seems historically unlikely. It is more likely that an owner of the ox is threshing his own grain or someone else’s, or that a renter/borrower of the ox is threshing his own grain. We must reason our way through the situation, asking if one or more of these three remaining options makes more sense of the surrounding literary context, the cultural situation, and the divine motivation.

If the command is directed to the owner of the ox—whether threshing in his own field or in another’s—it is difficult to understand why the stipulation is required in the first place. Oxen were viewed as property, and there was a built-in motivation for maintaining one’s property to perform at a maximal level. It is difficult to see why the command would make it into the Mosaic law given the self-interest that would already ensure such actions. As Jan Verbruggen notes in his excellent article on this verse, “The economic value of the ox far outweighs the value of the threshed grain that an ox could eat while it is threshing. . . . Economically, it would not make sense if the owner of the ox muzzled his own ox while it is doing hard labor.”

By process of elimination, this leaves us with the situation of a man borrowing or renting an ox to thresh his own grain. In that event, his self-interest would entail preserving as much of his threshed grain as possible; on the other hand, he would have no intrinsic motivation to let the ox eat of his grain. If the animal ended up in a weakened state or unhealthy as a result, the situation does not result in any economic loss on his end. This, then, seems like the most plausible situation for requiring a command. The covenant stipulation works against the selfish motive for a man to take advantage of another man’s property. (To use a modern analogy, at the risk of anachronism, this is the reason that rental stores today have agreements about returning rented equipment in good working order; they know that when someone doesn’t own something there is an increased propensity for recklessness and lack of diligent care.)

If this line of reasoning is correct, it cuts against the interpretive strategy taken by commentators like Raymond Brown: “Although all the other laws in this passage concern human rights, a commandment is suddenly introduced which protects animals from owners who are more concerned about working them hard than feeding them well.” This interpretation assumes (without argument, or without considering any other alternative) that it is the owner of the oxen who is receiving this command. Further, it assumes that the primary motivation is the protection of the animal. While not wanting to deny Yahweh’s compassion for animals as part of his created order and in accordance with his attributes, it is difficult to account for this interpretation in the context. It seems that Verbruggen is on more solid footing here: “If it was just a humanitarian law for the ox, the law is clearly at odds with its context. However, if it is a law dealing with the economic responsibility of someone using someone else’s property, the law fits nicely in the context.” In other words, Deuteronomy 25:4 in context is not fundamentally a law about how to treat animals humanely but rather a law about how to treat properly treat the property you are borrowing or renting from someone. Seen in this light, v. 4 fits the original context quite well. Otherwise the verse is an anomaly which seems to stand out.

So What’s Going on in the New Testament?

In 1 Timothy 5:17 Paul writes, “Let the elders who rule well be considered worthy of double honor, especially those who labor in preaching and teaching.” In v. 18 Paul grounds this teaching with two quotations: “You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the grain” (Deut. 25:4) and “The laborer deserves his wages” (Luke 10:17; cf. Matt. 10:10). Paul’s point is that pastor-elders should not be taken for granted or taken advantage of, but rather should be adequately compensated for their gospel labors.

Paul’s citation of Deuteronomy 25:4 in 1 Corinthians 9:9 is more complicated and has generated more discussion. At the end of the day, the function and argument is the same. What was a general principle in 1 Timothy 5:18 now becomes a personal and specific instantiation of this idea. Here Paul is arguing that he and Barnabas have the right to receive adequate compensation for their ministry labors. The most striking feature for our purposes is that Paul seems to say that God is really not concerned about the oxen after all, which is in tension with the traditional interpretation that the primary purpose of Deuteronomy 25:4 is to protect the oxen (that is, the one doing the work).

Numerous interpretations have been put forth. For example, Fee argues that laws, by their very nature, “do not intend to touch all circumstances; hence they regularly function as paradigms for application in all sorts of human circumstances. . . . Paul does not speak to what the law originally meant. . . . He is concerned with what it means, that is, with its application to their present situation.”

More specifically, Ciampa and Rosner argue, “Paul’s statement need not (and should not) be taken as an absolute denial that the law was given for the sake of animals, but as a strong assertion that God is even more concerned about humans (and that he was particularly concerned to give guidance for the eschatological community of the church).”

Luther, in a typically humorous but insightful aside, says that this command can’t be for the oxen because “oxen can’t read!”

Calvin elaborates:

[T]hough the Lord commands consideration for the oxen, He does so, not for the sake of the oxen, but rather out of regard for men, for whose benefit even the very oxen were created. Therefore that humane treatment of oxen ought to be an incentive, moving us to treat each other with consideration and fairness. . . . God is not concerned about oxen, to the extent that oxen were the only creatures in His mind when He made the law, for He was thinking of men, and wanted to make them accustomed to being considerate in behaviour, so that they might not cheat the workman of his wages. For the ox does not take the leading part in ploughing and threshing, but man, and it is by man’s efforts that the ox itself is set to work. Therefore, what he goes on to add, ‘he that plougheth ought to plough in hope’ etc., is an interpretation of the commandment, as though he said, that it is extended, in a general way, to cover any kind of reward for labour.

These interpretations are legitimate so far as they go, but they lack nuance by focusing only on the “compassion” aspect of original while ignoring the “economic justice” factors that likely provided the motivation and impetus for the command in the first place.

To review my argument: Moses gave the command to provide for the ox, but ultimately to protect an Israelite from being unjustly treated at the hand of one who borrows or rents his ox. The one benefiting from the labor of an ox should not take economic advantage of the owner of the ox.

Once this is seen, rich texture is added to Paul’s use of this verse. His point is not really that the Corinthians should have compassion or mercy for him and Barnabas, but that this is a matter of fundamental justice. The issue is not really kindness, but rights. When Paul says this is not really about the oxen, he is pointing to this wider and deeper reality at play in this verse as it was originally to be understood. Therefore the Corinthians should want to provide appropriate compensation as an expression of justice, even if Paul ultimately rejects the offer.

Help on the New Testament Citing the Old

If this minority interpretation—which is indebted to Verbruggen’s helpful work—is correct, then there are at least two implications for understanding how the New Testament cites the Old Testament: (1) never ignore the original OT context; (2) be slow to assume that the NT writers are quoting things out of context. And even if my view is wrong, these two principles still apply!

For help on these questions, one of the shortest and most accessible introductions is C. John Collins’ essay, “How the New Testament Quotes and Interprets the Old Testament,” found in the ESV Study Bible (pp. 2605-2607), which includes an extensive chart on all of the “Old Testament Passages Cited in the New Testament” (pp. 2608-2611). This is reprinted in Understanding Scripture, pp. 181-198.

The go-to reference book is the Commentary on the New Testament Use of the Old, edited by Carson and Beale. This book probably belongs on every pastor’s shelf.

And undoubtedly the best how-to guide on this subject is now Beale’s new Handbook on the New Testament Use of the Old Testament: Exegesis and Interpretation.

How Important Is Complementarianism?

John Piper, Ligon Duncan, Russell Moore, and Greg Gilbert at a panel of the 2012 Together for the Gospel (April 2012):

Tim Keller, Don Carson, and John Piper at the Gospel Coalition council members’ meeting (May 2012):

If you are new to this subject, here are some resources I would recommend starting with:

1. John Piper and Wayne Grudem “50 Crucial Questions About Manhood and Womanhood.” This is a free PDF that gives concise answers to 50 questions. This is the place to start.

2. If you want to hear the audio or read the notes of a weekend seminar, looking at passages and objections and application in more depth, take a look at this free seminar by John Piper.

3. For introductions written by women, consider Carrie Sandom, Different by Design: God’s Blueprint for Men and Women and Claire Smith, God’s Good Design: What the Bible Really Says About Men and Women.

Is This the High Priestly Palace Where Jesus Stood Trial?

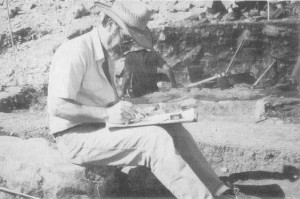

In the 1970s, renowned archaeological architect Leen Ritmeyer, with his training in both ancient architecture and conservation of historic sites, supervised the team that reconstructed a large palace not far from the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. He has tentatively identified the “Palatial Mansion” (or “Herodian Mansion”) as the place of residence for Annas the high priest. If this is correct, then this would be a “look inside” the first phase of Jesus’s Jewish trial. And it may explain things like where the courtyard was located and how Jesus could look at Peter though they were in two different locations (Jesus inside and Peter outside, warming himself by a charcoal fire).

In the 1970s, renowned archaeological architect Leen Ritmeyer, with his training in both ancient architecture and conservation of historic sites, supervised the team that reconstructed a large palace not far from the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. He has tentatively identified the “Palatial Mansion” (or “Herodian Mansion”) as the place of residence for Annas the high priest. If this is correct, then this would be a “look inside” the first phase of Jesus’s Jewish trial. And it may explain things like where the courtyard was located and how Jesus could look at Peter though they were in two different locations (Jesus inside and Peter outside, warming himself by a charcoal fire).

In doing background research for a forthcoming volume co-authored with Andreas Köstenberger (Jesus’s Final Week: An Easter Chronology and Commentary), I corresponded with Dr. Ritmeyer, who was kind enough to answer a few questions and to share some of his reconstruction drawings with us.

How big is the Palatial Mansion?

The footprint of this magnificent building is 6,500 sq. feet. However, as the whole building was two stories high, the usable living space was almost twice as large. No other private residence of this size has been excavated anywhere in Israel.

Where is it located?

The Palatial Mansion is located in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. It was excavated under the leadership of the late Prof. Nahman Avigad in 1973 and ’74 and later restored from 1985-’87. The Palatial Mansion is now part of the Herodian Quarter of the Wohl Museum that is open to visitors and is located on 1 Hakara’im Street, off the main Hurva Square in the Jewish Quarter.

What is it about the location and the features of the building suggest to you that this might be the palace of the high priest?

There is no doubt that this Mansion was occupied by priests that served in the Temple, especially as it was located on the eastern slope of the Upper City just opposite the southwest corner of the Temple Mount. From the Mansion it was only a short walk from here to the Royal Bridge whereby the priests could cross directly to the Temple platform without first having to descend into the Tyropoeon Valley.

The Palatial Mansion is the largest of the six dwellings that were excavated in this area and that are now incorporated in the Wohl Museum. These dwellings are the finest examples of Herodian architecture, with mosaic floors and walls decorated either with fresco or stucco.

Could you “walk” us through it and describe what we would see?

Its overall plan is centred round a paved courtyard. The entrance to the building was from the west via steps which led down from an entrance door. This led into a vestibule whose mosaic floor with a central rosette pattern was found almost completely intact with the charred beams of the ceiling lying on top of it.

From the vestibule, one could either turn into the fresco room on the right, which had panels painted in red and yellow on its plastered walls in the style of the Pompeian frescoes or, to the left, into the magnificent Reception Room with its stuccoed walls and ceiling.

Proceeding straight on from the vestibule, the visitor entered the courtyard, from where the rooms of the eastern wing could be reached. Of this wing only one of the ground floor rooms, a bathroom, has been preserved. This contained a low bench and a stepped sitting pool. Its floor was paved with a simple patterned mosaic. The bathroom was probably used before descending into one of the two mikvehs [ritual baths] that lay beneath the courtyard.

A stairway in the northern side of the courtyard leads down to the basement level of the eastern wing. Again there is a vestibule from which one could gain access to a large vaulted storeroom on the west. On the basement’s eastern end were two additional mikvehs, one of which had a side bath. The second mikveh was much larger and had a vaulted ceiling. This mikveh was exceptional in that it had a double doorway and an entrance porch paved with mosaic.

The Mansion stands out from the other dwellings in that it had four mikva’ot (ritual baths) which is quite unusual and has no parallel in any building in Jerusalem or in all of the Land of Israel.

All of the above, coupled with the traces of a great conflagration found in the Palatial Mansion, point to a possible identification of this residence with the palace of Annas, the High Priest. Annas’ Palace is recorded in Josephus’ War 2.426 as having been burnt, together with the Palace of Agrippa and Bernice, in A.D. 70.

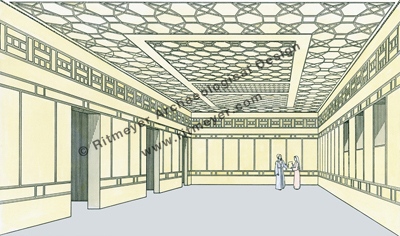

Tell us a little bit about the size and features of reception hall, where the first phase of the trial before part of the Sanhedrin may have taken place.

The Reception Room of the Palatial Mansion, which would better be described as a hall, measures 33 feet by 21 feet. Because of its large size, it is assumed that it was used to receive guests and for various functions. The walls of this magnificent room were decorated with white stucco. The northern wall was in the best state of preservation, with the stucco remains preserved almost to the height of the ceiling.

The basic decorative pattern consisted of broad panels in between two bands of imitation masonry, modelled on “headers and stretchers.” However, on the basis of the stucco remains of the northern wall that extended to the greatest height, it was clear that there was an additional band of decoration just below the ceiling. The ceiling was destroyed, but many ceiling fragments were found lying on the floor. All the pieces showed geometrical patterns in relief—raised sections separated by a narrow band which had a groove cut in its centre which was picked out in red paint. It was clear that the original design must have been divided into two separate parts, as some fragments had an “egg and dart” motif, which is a pattern based on alternate eggs and arrow-heads, while the remainder were plain. My reconstruction design shows that a band of just over 3.5 feet broad of hexagonal patterns surrounded the ceiling of the room, while the central panel was divided into two squares of a design based on octagons, with a narrow strip in between. The octagonal pattern was formed using the fragments with the “egg and dart” design, while the hexagonal pattern, which had as its basis four hexagons attached to the four sides of a square, used the plain fragments. This design is conjectural but fits in well with the room and has definite parallels with patterns preserved in the vaulted stucco ceilings at Pompeii dating from the first century B.C. and also in the stone ceilings of Baalbek and Palmyra.

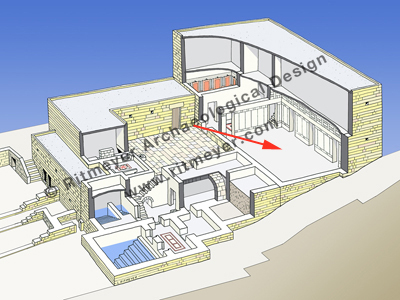

Let me review what we know from the biblical accounts about the place of Peter in this story. After Jesus’s arrest, Peter and John followed the arresting party at a distance. Because John “was known to the high priest, he entered with Jesus into the courtyard of the high priest, but Peter stood outside at the door.” John put in a good word for Peter, and the servant girl guarding the door let Peter in to the courtyard (John 18:15-16). So the other disciple, who was known to the high priest, went out and spoke to the servant girl who kept watch at the door, and brought Peter in. While Jesus was inside the residence, Peter stood with the guards and servants in the middle of the courtyard outside, warming himself by a charcoal fire (Matt. 26:58, 69-71; Mark 14:54, 66-67; Luke 22:54-55, 61; John 18:18). In the Palatial Mansion you reconstructed, where was the courtyard from the Reception room?

To the east of the Reception Room was a large open stone-paved courtyard round which all the rooms were arranged.

So if Jesus was inside (on trial) and Peter as outside (in the courtyard), how could Jesus turn and look at Peter?

The Gospel record speaks of Jesus being interrogated by the priests, elders, and council in the palace of the High Priest, which at that time was Caiaphas, son-in-law of Annas (Matt. 26.57; Mark 14.53; Luke 22.54). However, John 18:13 intimates that the director of the first interrogation was Annas himself. The task of harmonising this gospel record with those of the Synoptic gospels would be far less difficult if we were to assume that the old High Priest’s Palace of Annas continued to be used for such functions, even if it was a relative of his and not he himself that held the office. He was, after all, a type of éminence grise who continued to direct affairs by promoting members of his own family to the high priest’s office, long after he himself had vacated it.

It must be said that the plan of this Palatial Mansion, with its central courtyard and lavish reception hall, makes a visualisation of the scene of Peter warming himself at an outdoor fire while Jesus is interrogated inside, eminently possible. To heat the rooms of the Palatial Mansion, wooden beams, that had been previously prepared and partly burnt, would have been ignited and the glowing embers placed in braziers that were put in the rooms. It is not difficult to imagine Peter standing near the burning logs to warm himself.

After Peter was identified as a follower of Jesus, he tried to leave the building (Matt. 26:71). First, he would have removed himself from the light of the fire and then edged closer to the exit. Here, at the southwest corner of the courtyard, there is a direct line of vision to the centre of the Reception Room. The arrow in the picture shows the line of vision from the corner of the courtyard to the centre of the Reception Room.

This makes it possible to visualise how Jesus, if he was standing in the middle of this room, could look back to see Peter standing in this part of the courtyard (where the young lady in the photograph is standing—see picture below). This is the only scenario that allows the tragic meeting of eyes described in Luke 22:61: “And the Lord turned, and looked upon Peter and Peter remembered the word of the Lord, how he had said unto him, Before the cock crow, thou shalt deny me thrice.”

There is one particular place in a corner of the courtyard, from where, looking through two open doorways, one has a straight line vision to the centre of the Reception Room. It is chilling to stand at that place and imagine Jesus looking back at Peter after the cock had crowed the final time. This picture shows where Peter would have stood in the corner of the courtyard, viewed from the centre of the Reception Room.

Here’s a detail I recently noticed for the first time in rereading the Gospel accounts. Mark 14:66 says that Peter was in the courtyard “below.” What could that mean?

The Mansion is built on a slope, going down in an easterly direction. The entrance was higher than the courtyard, so Peter would have come down to where he was. To leave the palace, he would have had to climb up some steps before leaving by the front door.

What happened to Annas’ palace?

As previously mentioned, Josephus records in War 2.426 that the Palace of Annas the high priest was burnt, together with the Palace of Agrippa and Bernice in A.D. 70. When the Palatial Mansion was excavated, there was evidence that the building had been destroyed in a massive conflagration. The same fate befell most of the buildings of the Upper City, a prime example of which is the Burnt House.

After the destruction of Jerusalem, this area was buried by destruction debris and not uncovered until the reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter in the wake of the wanton Jordanian destruction that was carried out between 1948 and 1967. We are very fortunate to have been able to excavate and restore this most important historical building.

For higher quality pictures and other drawings, see the Ritmeyers’s CD vol. 2, Jerusalem in the Time of Christ, and the book, Jerusalem in the Year 30 AD.

August 27, 2012

Where’d All These New Calvinists Come From? A (Serious) Top 10 List from Mark Dever

Before Mark Dever became a pastor he did his PhD work in historical theology at the University of Cambridge. In 2007, with the resurgence of evangelical Calvinism, he did a series of 10 blog posts that combined his historical gifting with his insider look at the roots (under God) of what has been happening and why.

Before Mark Dever became a pastor he did his PhD work in historical theology at the University of Cambridge. In 2007, with the resurgence of evangelical Calvinism, he did a series of 10 blog posts that combined his historical gifting with his insider look at the roots (under God) of what has been happening and why.Of course, theologically, the answer is “because of the sovereignty of God.” But I’ve never been convinced by hyper-Calvinism’s argument that because God has determined the ends, the means don’t matter. Means do matter. And as a Christian, as an historian who had lived through the very change I was considering, I wondered what factors had been used by God.

The whole series is worth rereading for those who are interested in this kind of thing. I’ve provided a table of contents below, with the title of his conclusions as the title:

Charles H. Spurgeon

D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones

The Banner of Truth Trust

Evangelism Explosion

The inerrancy controversy

Presbyterian Church in America (PCA)

J. I. Packer

John MacArthur and R. C. Sproul

John Piper

The rise of secularism and decline of Christian nominalism

Some additional pieces worth reading:

Trevin Wax’s suggested supplement to Dever’s list, focusing on 9/11.

Collin Hansen’s CT cover story and the book that brought the conversation into the public square.

If Dever’s list were ongoing and updated, I would also add the following factors (focusing on the American context):

The publication and explosive success of Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology

The Passion conferences

September 11, 2011 (per Wax’s suggestion above)

The role of Christian publishing (Eerdmans, P&R, Baker, and now Crossway and a number of smaller publishers)

The steady growth of seminaries (e.g., Westminster Theological Seminary, Westminster Seminary California, Covenant Theological Seminary, Reformed Theological Seminary, the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, etc.)

The rise of organizations devoted to developing and networking around a God-centered, gospel-driven vision. Dever mentions MacArthur, Sproul, and Piper—associated with Grace to You, Ligonier, and Desiring God. To that list could be added the Gospel Coalition, Redeemer City to City, Together for the Gospel, Acts29, 9Marks, Sovereign Grace Ministries, etc.

The Inexhaustibility of the Cross

“The cross is so extensive a field for meditation, that, though we traverse it ever so often, we need never resume the same track: and it is such a marvellous fountain of blessedness to the soul, that if we have ever drunk of its refreshing streams, we shall find none other so pleasant to our taste.”

—Charles Simeon, Horae Homileticae (1832), vol. 8, p. 323.

“The cross is the foundation of the Bible: If you have not yet found out that Christ crucified is the foundation of the whole volume, you have hitherto read your Bible to very little profit. Your religion is a heaven without a sun, an arch without a keystone, a compass without a needle, a clock without a spring or weights, a lamp without oil. It will not comfort you; it will not deliver your soul from hell.”

—J.C. Ryle, Old Paths (London, 1977), p. 248.

“There is no end to this glorious message of the cross , for there is always something new and fresh and entrancing and moving and uplifting that one has never seen before.

—D. Martyn Lloyd-Jones, The Cross: God’s Way of Salvation (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 1986), xiii.

“Oh that I could have the cross painted on my eyeballs, that I could not see anything except through the medium of my Savior’s passion! Oh, Jesus . . . let me wear the pledge forever where it is conspicuous before my soul’s eyes.”

—Charles Haddon Spurgeon, “The Lord’s Supper—Simple But Sublime!” (1866), Sermon #3151, Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit.

All cited in James M. Gordon, Evangelical Spirituality (SPCK, 1991; Wipf & Stock, 2006).

August 26, 2012

God’s Faithfulness and Goodness Even in a Parent’s Worst Nightmare

We need to see and hear testimonies like this over and over. Here is the story of the Harms family at The Journey in St. Louis:

HT: Stephen Miller

August 25, 2012

A Message to Itchy Ears

A very powerful poem from Jackie Hill at P4CM 2012 pleading for sound doctrine instead of itchy ears:

HT: Tim Brister

August 24, 2012

What Is It About “The Gospel” that Would Help Here?

A self-described “mild rant” from Thabiti Anyabwile provocatively saying that the answer to every Christian question is not “the gospel.”

Of course, I’m not tired of hearing the actual gospel. Let us all determine to know nothing but Jesus Christ and Him crucified. But let us also learn that the apostle taught a lot of things about Jesus Christ, His crucifixion and resurrection without lackadaisically tossing out a few cliched references to “the gospel”. He meditated on and expanded the message of God’s redemption through His Son in many varied arguments, tropes, and statements. But that’s not what’s trotted out in today’s situations of human need. We’re not getting deep reflections on the Person of Christ—His offices, nature, and work. We’re not given robust explanations of the cosmic renewal of all things in Christ as the grounds of hope and joy no matter the circumstance. We’re not having very many conversations that explore the dynamics of repentance and faith when we’re tempted to blast our mechanic. Too many Christians lazily tell us we need “the gospel” the way little kids answer every spiritual question with a reflexive “Jesus.”

As blasphemous as it sounds, “the gospel” is not the answer to every question. It’s not enough. What about Jesus do I need to know that I’m unaware of when the medical report comes back? I’m sure there’s something I’m likely to miss, but “the gospel” doesn’t communicate it. What about joblessness is addressed by Jesus when I’ve sent out the 132nd resume with no response? What specific promises should I hold onto in order to persevere through life without income in a monied economy? Help me by telling me the actual message. Bury my nose in the text of Scripture if you can. My husband of 50 years just died? Can you not tell me at length something about the resurrection—Jesus’ and ours—and the adoption the entire creation awaits to be fulfilled? Can you not reduce the entire scope and swoop of Christ’s redemptive work to the mere facts of the gospel, but along with those facts sketch and paint something of the goodness of this news? I know I need Jesus. I know the news is good. I need reminders specifically enumerating the reasons why. That’s what plants, roots, and grows enduring faith. That’s how we actually get to know Jesus more personally-by finding out what He’s like in the crucible of life.

I wonder if the cliff notes references to “the gospel” doesn’t blunt our understanding, meditation, application, and enjoyment of the incredible realities accomplished for us through the Son of God. Are we inoculating people against the actual gospel with our frequent but unexplained references to “the gospel”?

You can read the whole thing here.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers