Justin Taylor's Blog, page 197

August 9, 2012

Les Misérables

In recently watching the first few numbers from the 10th anniversary of the musical Les Misérables, I wondered: in contemporary culture is there another example of something so popular where the Christian themes are so numerous and explicit?

See, for example, the number of themes you can identify in these first 10-15 minutes:

As many readers will now, this December (2012) a new film version—with some of the musical numbers—will appear, starring Hugh Jackman (Valjean), Russell Crowe (Javert), and Anne Hathaway (Fantine)—and also including Sacha Baron Cohen as Thénardier and Colm Wilkinson (the original Valjean in the London musical) as the Bishop of Digne. It is directed by Tim Hooper, who previously directed The King’s Speech.

Those who want to read the book will probably want to consider the recent edition by acclaimed translator Julie Rose.

John Piper writes, “We have little hope that his spiritual pilgrimage led him to Christ and heaven. But in the providence of God, and by the grace he scatters so liberally among his adversaries, Hugo was brilliant in his blindness. The imago dei and the remnants of his Christian roots break forth—to the praise of his Maker.” Piper reproduces some of his favorite quotes from the novel here. For more extensive list, see this series of excerpts collected by Trevin Wax.

August 8, 2012

An Interview with Bob Kauflin

Bob Kauflin of Sovereign Grace Music and the author of the excellent book Worship Matters is interviewed by Stephen Miller of The Journey in St. Louis:

On Being a Mirror: The Image of God, the Longing for Significance, and the Meaning of Prayer

John Piper, preaching in 1985, said, “I believe all of you somewhere within your heart want to be the instruments of God’s power, and therefore, even if you don’t feel like it now, there is buried somewhere in your subconscious the longing to be a man or a woman of fervent and effective prayer.”

He explains how he knows this:

The reason I am confident of this is that every one of you is created in God’s image. Each one of you was created to be a conscious mirror of God’s image. You were created to consciously reflect his glory like a mirror of God’s image. Before sin entered the world, I think Adam and Eve had an overwhelming longing to be used by God to image-forth his power and wisdom and love in the world. They wanted to be mirrors of his glory.

And that longing is deep within every person today, but it has been distorted by sin. In a sense, the distortion is only slight; but it is the difference between day and night. It is the difference between wanting to reflect his face and wanting to take his place.

Piper explains the glory and function of a mirror, starting in the Garden:

The glory of a mirror is to put its face to the light and to let that light shine. This is what mirrors are made for. This is the deep longing of the heart. But then sin entered the world and its first manifestation was Adam and Eve’s discontent with being mirrors. They began to want to be their own source of light. They began to feel that mirrors are just glass with a thin black coating of tin and mercury.

They suddenly became conscious of the fact that to be a good mirror you have to turn whichever way the light moves. You can’t be your own master. So they chose to be their own source of light; they turned their brilliant mirror-faces away from God, and now all they can do is block his light and cast a shadow across the world.

But I want you to see that the longing of Adam and Eve to be the light is a distortion of a legitimate longing, namely, to reflect the light. The Bible teaches that everyone since the fall of Adam and Eve is born with these same distorted longings. We come into the world longing to be God. We want the world to revolve around our interests.

We want to decide for ourselves which way to turn our faces. We want people to esteem us and admire us and compliment us. We don’t like the thought of being a mirror which has no beauty except in the thing it reflects. We don’t like the idea of having to turn our face wherever the light wants to go. We want to be our own light. We want to be God.

This comes with our fallen humanity. It is the very essence of sin. If you are honest, you will admit that you have felt this way. But this universal experience of sin is Satan’s distortion of something wonderful. And the wonderful thing is the pure and righteous longing to be used by God to reflect his glory in the world.

It’s not wrong to want to be significant. It’s wrong to want your significance to reside in yourself instead of in the one you reflect. It’s not wrong to want to be important. It’s wrong to want your importance to be in yourself instead of the one you reflect. It’s not wrong to boast, but “Let him who boasts, boast in the Lord!”

Concealed deep beneath our pride and our craving for esteem and our love of power and influence is a good thing that has been distorted, namely, the longing to be a mirror of God. To be a mirror of God is the highest honor to which a creature can aspire. And the most ludicrous sight in the world is a created mirror turning away from the light of God and then trying on its own to make a little spark to brighten the shadow it casts on the world.

Piper goes on to apply this to prayer, which is a way we mirror God:

A mirror faces away from itself to its source of light so that it might have some use in the world, and prayer faces away from itself toward God so that it might be of some use in the world.

A mirror is designed to receive light and channel it for the good of others, and prayer is designed to receive grace and channel it for the good of others.

The value of a mirror is not in itself, but in its potential to let something else be seen. And the value of prayer is not in itself, but in its potential to let the power and beauty of God be seen.

A mirror is utterly dependent on the source of light from outside itself, and prayer is the posture of the childlike, utterly dependent on the resources and kindness of the heavenly Father.

So praying is the way we mirror God. And if I am right that each of you, in the image of God, has a deep desire to be a mirror of God, then it is also true that, even if you don’t feel like it now, there is buried somewhere in your subconscious the longing to be a man or a woman of fervent and effective prayer.

You can read the whole sermon here.

August 7, 2012

Plantinga and Wolterstorff on Being Christian in the Academy

Some wise words from two giants in the field of philosophy on how to be a Christian in academia:

HT: Frank Beckwith

When Will Christ Return?

And this gospel of the kingdom

will be proclaimed

throughout the whole world

as a testimony to all nations,

and then the end will come.

—Matthew 24:14

New Testament scholar George Eldon Ladd, writing in the 1950s, comments:

The subject of this chapter is, When will the Kingdom come? I am not setting any dates. I do not know when the end will come.

And yet I do know this: When the Church has finished its task of evangelizing the world, Christ will come again. The Word of God says it.

Why did He not come in A.D. 1oo? Because the Church had not evangelized the world.

Why did He not return in a.d. 1000? Because the Church had not finished its task of world-wide evangelization.

Is He coming soon? He is—if we, God’s people, are obedient to the command of the Lord to take the Gospel into all the world.

. . . “How are we to know when the mission is completed? How close are we to the accomplishment of the task? Which countries have been evangelized and which have not? How close are we to the end? Does this not lead to date-setting?”

I answer, I do not know. God alone knows the definition of terms. I cannot precisely define who “all the nations” are. Only God knows exactly the meaning of “evangelize.” He alone, who has told us that this Gospel of the Kingdom shall be preached in the whole world for a testimony unto all the nations, will know when that objective has been accomplished.

But I do not need to know. I know only one thing: Christ has not yet returned; therefore the task is not yet done. When it is done, Christ will come. Our responsibility is not to insist on defining the terms of our task; our responsibility is to complete it. So long as Christ does not return, our work is undone. Let us get busy and complete our mission.

. . . Here is the motive of our mission: the final victory awaits the completion of our task. “And then the end will come.” There is no other verse in the Word of God which says, “And then the end will come.”

When is Christ coming again? When the Church has finished its task.

When will This Age end? When the world has been evangelized.

“What will be the sign of your coming and of the close of the age?” (Matt. 24: 3). “This gospel of the kingdom will be preached throughout the whole world as a testimony to all nations; and then, and then, the end will come.” When? Then; when the Church has fulfilled its divinely appointed mission.

Do you love the Lord’s appearing? Then you will bend every effort to take the Gospel into all the world. It troubles me in the light of the clear teaching of God’s Word, in the light of our Lord’s explicit definition of our task in the Great Commission (Matt. 28: 18-20) that we take it so lightly. “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me.” This is the Good News of the Kingdom. . . . All authority is His. “Go ye therefore.” Wherefore? Because all authority, all power is His, and because He is waiting until we have finished our task. His is the Kingdom; He reigns in heaven, and He manifests His reign on earth in and through His Church. When we have accomplished our mission, He will return and establish His Kingdom in glory. To us it is given not only to wait for but also to hasten the coming of the day of God (II Pet. 3:12). This is the mission of the Gospel of the Kingdom, and this is our mission.

George Eldon Ladd, The Gospel of the Kingdom: Scriptural Studies in the Kingdom of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1959), ch. 9, “When Will the Kingdom Come?”

August 6, 2012

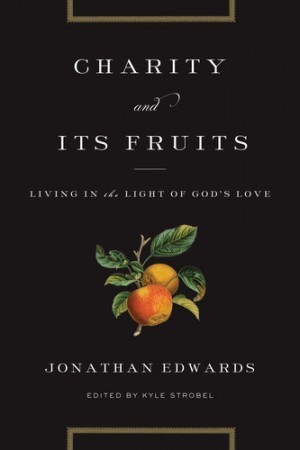

Reading “Charity and Its Fruits” Today: An Interview with Kyle Strobel

Jonathan Edwards scholar Kyle Strobel (PhD, University of Aberdeen) has edited a new, unabridged edition of Edwards’s classic, Charity and Its Fruits: Living in the Light of God’s Love (Crossway, 2012). He is a brief interview we did together:

R.C. Sproul puts Charity and Its Fruits among the top books he recommends. Tim Keller and John Piper have both cited it as deeply influential for their understandings of justice, virtue, and love. But it doesn’t seem that many people today have read it. Why should they?

R.C. Sproul puts Charity and Its Fruits among the top books he recommends. Tim Keller and John Piper have both cited it as deeply influential for their understandings of justice, virtue, and love. But it doesn’t seem that many people today have read it. Why should they?

Yes, compared to Edwards’s other famous works Charity is often forgotten about. It is both the most beloved and the least read of his great works.

I think it is incredibly important for people to read Charity for several reasons.

First, what Edwards is really providing in these sermons is a theology of love. He is utilizing 1 Corinthians 13 as the way into a theology of love, but above all this is a treatise that gets to the heart of a Christian life defined by love of God and love of neighbor.

Second, of all of Edwards’s works, it is probably the best introduction to his thought. As important as Religious Affections, Freedom of the Will, and the Two Dissertations are (End for Which God Created the World and True Virtue), Charity really cuts across all of Edwards’s thought. You get the importance of religious affection, virtue, glory, etc., and you get it woven together in a pastoral discourse.

Last, and one of the more important in my mind, is that you get a great example of what it means to be a theologian as a pastor. Edwards is shepherding a congregation with these sermons, a congregation he knows well. As universally helpful as this work is, it started out as a very particular word to a particular people. If you want an example of a pastor who is theologically oriented, then this is about as good of an example as you will get.

Tell us a little bit about the underlying text.

Well, as readers might know, there are several other editions of Charity and Its Fruits available. What makes them different is that they use a highly edited text that was first published by Edwards’s great, great grandson in 1852. The text I used comes from the Yale edition of Edwards’s works, which is bound together with the rest of Edwards’s ethical writings and costs about $150.00! After lengthy negotiations with Yale I was able to get permission to use their text for my edition.

What makes this text unusual is that it goes back to Edwards’s original sermon manuscripts. Edwards’s great, great grandson didn’t like some of Edwards’s language and emphases, so he edited that out (they were a bit more open to do that kind of thing than we are). By going back to the original we have Edwards’s real emphases and language open to us.

What work did you do to the original manuscripts?

Edwards is never easy to read. I wanted to put out a volume for the many people who want to read more of Edwards (or even just some of Edwards) but have never been able to do it. I sat down and tried to think through what makes Edwards so difficult, and a couple of things came to mind.

First, his use of language is often times so outdated and technical that he can seem impenetrable. So I defined all of these terms either in footnotes or textboxes.

Second, Edwards was a systematic thinker who never wrote a systematic theology (he died before he could), so it is often hard to see how his thought coheres together. I included in my introduction a brief overview of key theological principles that will help people understand what his theology is about.

Third, as in all great theologians, Edwards’s spiritual and doctrinal writings are not divided but united together. In both the introduction and conclusion I have developed aspects of his spiritual thought as well as advice on how to read his work in such a way as to hold these two things together.

Last, for those new to Edwards and theology, one of the most frustrating aspects of his writings is just how packed they are with dense theological ideas. To remedy this stumbling-block, I added 174 textboxes throughout the book that explain these difficult ideas. Sometimes I just let Edwards speak for himself and quote something he said elsewhere with greater clarity. Often, I step back and outline what he is saying and why he is saying it. In other words, I try to pull back the curtain a bit to unveil what makes Edwards’s theology tick.

Sproul once wrote about these sermons: “Instead of being a maudlin, romantic wedding recitation, Edwards’ treatment of 1 Corinthians 13 becomes one of the most demanding and humbling pieces on divine revelation we may ever encounter. Under Edwards’ scrutiny, our failure to live the love we’re called to is so clear that we are driven once more to cling to the cross.” How would you summarize Edwards’s understanding of the relationship between the cross and spiritual formation?

As a good Reformed theologian, Edwards’s theology is all about God. The place we come to meet God is the cross, because that is where God has met and redeemed us. One of the great mistakes made in discussions (and practices) of spiritual formation is to leave the cross and try to grow ourselves. Rather, for Edwards, the cross embodies the posture of the Christian—dependence, submission, and humble yearning for God. Therefore, instead of a discussion of “spiritual disciplines” we find an emphasis on “means of grace.”

What is frustrating is that Edwards’s spirituality is very undeveloped in the field, with virtually no resources on it. Alongside of this new volume of Charity and Its Fruits, I have tried to address this in a forthcoming book, Formed for the Glory of God: Learning from the Spiritual Practices of Jonathan Edwards (due out next Spring from IVP). I answer your question in full in that book, which I wrote at a popular level—it is Edwards’s spirituality without all the difficulty in reading Edwards!

How did you first become interested in Edwards and why did you stay interested in studying his theology?

When I was starting my PhD I jumped from one topic to another and from one thinker to another until I landed on Edwards. I had never read him before (other than snippets here and there). What amazed me was how little work has been done on Edwards from a theological standpoint. I would venture to guess that of all the thinkers who are clearly the “great theologians,” Edwards is the least developed. Most of the good work done on Edwards is from an historical standpoint rather than a theological one, which is why I think his theology rarely gets utilized even though his person is revered.

What I love about Edwards was his adamant refusal to bifurcate the theological task. Edwards was a pastor and yet wrote high-level “academic” theology—he knew that theology was a task of the church and not the academy. He didn’t separate spirituality from theology or his vocation as pastor from theology but saw the deep integration of all things. He was a biblical scholar just as much as a theological one, and he recognized that pastoral care was a part of his calling (even though he believed he wasn’t good at it). I believe that one of the great mistakes of the church today is shirking away from aspects of our calling because we don’t believe we are good at it. We want to minister out of strength rather than grasp that God’s grace is perfected in weakness. Edwards came to understand the nature of weakness: in his pastoral calling, in his firing, in his ministry to the native Americans and eventually Princeton. I don’t think that can be underestimated.

Ultimately, I stuck with Edwards because he truly is a great theologian. I don’t agree with everything he said, but he grasps what it means to be a theologian. As someone who wants to think well for the glory of God, I have found that Edwards is a good mentor for this journey.

Why can Edwards be so hard to read at times, and why do you think his writings continue to resonate both in the academy and in the church?

Like every great theologian, Edwards resonates to the church and academy because he wielded everything the Lord gave him for the glory of God. He understood with the early church theologians that theology and spirituality were one, and that theology must start and end with God.

Like medieval theology Edwards focused his attention on careful analysis of virtue and doctrine, seeking to be faithful to his call as witness to the God of glory.

Like the Reformers Edwards battled against false doctrine and yet also battled against sinfulness in his community and his own heart.

Like every era before him, Edwards understood that being given eyes to see and ears to hear means that we are privy to a world saturated with the glory and beauty of God—a world that cries out in praise of its Creator.

Like all great theologians, Edwards’s work teaches us the melody of that great song.

What makes Edwards hard to read is a bit more difficult to explain. We live in an age where theology and spirituality have nothing to do with each other and are even pitted against each other as mutually exclusive. We tend to invoke pragmatics in church life, thinking theology belongs to the academy. We leave things like ethics to philosophers, and look to our preachers to give us a simple plan for growth. In Edwards we find something totally different and foreign. Some of that difference is just cultural—Edwards lived in a different time, spoke an older form of English, and preached in a different and more academic mode. It would be a mistake to underestimate how hard it is to get beyond that. That said, I think more of it is how foreign he is to us. But it is that foreignness that is so intriguing, provocative, and attractive. It is hard to put into words, but every great theologian has the trait of being able to cut across debates and differences to captivate people with their ability to cast a vision of who God is. Edwards truly is a great theologian.

The book is available from Amazon, WTS Books, and others. You can read Strobel’s 25-page introduction online for free.

Four Rules for Preachers

Phillip Brooks—one of the great American preachers of the 19th century—offered this counsel in his Bohlen Lectures on Preaching delivered before the Divinity School of Yale College in January/February 1877:

Phillip Brooks—one of the great American preachers of the 19th century—offered this counsel in his Bohlen Lectures on Preaching delivered before the Divinity School of Yale College in January/February 1877:

First, count and rejoice to count yourself the servant of the people to whom you minister. Not in any worn-out figure but in very truth, call yourself and be their servant.

Second, never allow yourself to feel equal to your work. If you ever find that spirit growing on you, be afraid, and instantly attack your hardest piece of work, try to convert your toughest infidel, try to preach on your most exacting theme, to show your self how unequal to it all you are.

Third, be profoundly honest. Never dare to say in the pulpit or in private, through ardent excitement or conformity to what you know you are expected to say, one word which at the moment when you say it, you do not believe. It would cut down the range of what you say, perhaps, but it would endow every word that was left with the force of ten.

And last of all, be vital, be alive, not dead. Do everything that can keep your vitality at its fullest. Even the physical vitality do not dare to disregard. One of the most striking preachers of our country seems to me to have a large part of his power simply in his physique, in the impression of vitality, in the magnetism almost like a material thing, that passes between him and the people who sit before him. Pray for and work for fulness of life above everything; full red blood in the body; full honesty and truth in the mind; and the fulness of a grateful love for the Saviour in your heart. Then, however men set their mark of failure or success upon your ministry, you cannot fail, you must succeed.

August 5, 2012

C. S. Lewis on the Three Parts of Morality

The band of the Titanic as depicted in "A Night to Remember."

C. S. Lewis describes two ways in which “the human machine” goes wrong:

One is when human individuals drift apart from one another, or else collide with one another and do one another damage, by cheating or bullying.

The other is when things go wrong inside the individual—when the different parts of him (his different faculties, and desires, and so on) either drift apart or interfere with one another.

He asks us to think of humanity as “a fleet of ships sailing in formation” and what makes it successful:

The voyage will be a success only, in the first place, if the ships do not collide and get in one another’s way; and, secondly, if each ship is seaworthy and has her engines in good order.

As a matter of fact, you cannot have either of these two things without the other.

If the ships keep on having collisions, they will not remain seaworthy very long.

On the other hand, if their steering gears are out of order, they will not be able to avoid collisions.

He then offers an alternative metaphor: “humanity as a band playing a tune.” “To get a good result,” he says, “you need two things”:

Each player’s individual instrument must be in tune and also each must come in at the right moment so as to combine with all the others.

These two elements are fairly obvious, but we often forget to identify the most important piece of information:

We have not asked where the fleet is trying to get to, or what piece of music the band is trying to play.

The instruments might be all in tune and might all come in at the right moment, but even so the performance would not be a success if they had been engaged to provide dance music and actually played nothing but Dead Marches.

And however well the fleet sailed, its voyage would be a failure it it were meant to reach New York and actually arrived at Calcutta.

Applying this to morality, Lewis says that ethics is concerned with three things:

Firstly, with fair play and harmony between individuals.

Secondly, with what might be called tidying up or harmonizing the things inside each individual.

Thirdly, with the general purpose of human life as a whole: what man was made for: what course the whole fleet ought to be on: what tune the conductor of the band wants it to play.

—C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, Book 3, Chapter 1 (emphasis added).

August 3, 2012

The Courage to Put Your Camera Away

So many things in life fall into this category—events you simply cannot bottle for later—like the birth of a child, the funeral of a loved one, a sunset, the presentation and enjoyment of a great meal, a surprise party, a concert, climbing out of a cold tent in the mountains and restoking the campfire as you watch the sun come up, sifting through the rubble of a flood or a fire, kissing your daughter’s forehead as the nurses wheel her off to surgery, asking your girlfriend to marry you, or watching a thunderstorm roll in.

In our amazing era of digital immediacy, I can tell the world where I am and what I’m doing while I’m doing it. I can present myself as a busy man living a rich and full life. I can take pictures of my meals, log my locations, snap photos of the people I’m with, and weigh in on what’s happening around the globe 140 characters at a time. But none of these things mean I’ve been paying attention.

The degree to which we are able to be present in the moment, psychologists say, is one of the chief indicators of mental health and security in our personal identity. I can buy that. And I would submit that this takes a lot of courage.

You can read the whole thing here.

August 2, 2012

Disability and the Gospel: How God Uses Our Brokenness to Display His Grace

Michael Beates’s book, Disability and the Gospel: How God Uses Our Brokenness to Display His Grace, is now available.

You can read online for free the introduction and the fourth chapter (on biblical conclusions and reflections).

John Frame writes, “”Mike Beates has been a good friend for twelve years, and I’ve observed his godly character as well as heard and read his insightful teaching. I have read Disability and the Gospel at several stages, and I recommend it highly. The church needs to be awakened to the presence of the disabled in our communities and, as Mike stresses, to the disabilities we all have as sinners in need of God’s grace. The book contains excellent exegesis, theology, and historical studies that make a powerful case. I don’t know a better place to hear God’s Word on this important matter. ”

Here is Joni Eareckson Tada’s foreword for the book:

Back in the mid-1960s when I first embraced Christ, I would tell people it was all about Jesus, but I had no idea what that meant. Sure, Christianity was centered on Christ, but mainly he was the one who got my spiritual engine started. As long as I filled up on him every morning during my quiet time, I was able to putter along just fine.

Things changed dramatically in 1967 after I crushed my spinal cord in a diving accident that left me a quadriplegic. I was frantic and filled with fear. Oh God, I can’t do this. I can’t live like this! This time I needed the Savior urgently. Every hour. Every minute. Or else I’ll suffocate, God! Suddenly, the Bible with all its insights about suffering and weakness became the supreme thing in my life. I spent hours flipping pages of the Bible with my mouth stick, desperate to understand exactly who God is and what his relationship is to suffering. It didn’t take long to find answers that satisfied. When it came to my life-altering injury, nothing comforted me more than the assurance that God hadn’t taken his hands off the wheel for a nanosecond. I discovered that a right understanding of God’s hand in our hardships was critical to my contentment. I also discovered how important good theology is.

Fast-forward more than three decades to the worldwide ministry I now help lead at Joni and Friends—a ministry to people with disabilities who anguish over the same questions I once did. As I travel around the globe, I hear, “What does the Bible say about my child who was born with multiple disabilities?” and “Why does God allow so much brokenness in the world?” My heart aches because these people often hear only silence (or experience rejection) from the body of Christ. Sadly, the church is ill equipped to answer the tough questions about God’s goodness in a world crumbling into broken pieces.

When it comes to suffering, I’m convinced God has more in mind for us than to simply avoid it, give it ibuprofen, divorce it, institutionalize it, or miraculously heal it. But how do we embrace that which God gives from his left hand? I have found a person’s contentment with impairment is directly proportional to the understanding of God and his Word. If a person with a disability is disappointed with God, it can usually be traced to a thin view of the God of the Bible.

Now you understand why I believe a “theology of brokenness” is desperately needed today—a theology that exalts the preeminence of God while underscoring his mercy and compassion to the frail and brokenhearted. It’s why I am so excited about the book you hold in your hands!

Disability and the Gospel provides exactly what the church needs today. I first met the author, Michael Beates, at a Reformed theology conference in 1992, and then, in the summer of 1993 at a family retreat that our ministry holds for special-needs families. Mike and Mary brought their five children including Jessica, their daughter with multiple disabilities. We struck up a conversation one afternoon and right away, I liked this man. I learned about his love for Reformed theology and his passion to preserve the integrity of God’s Word—yet he didn’t come across aloof and academic. Mike explained that years of raising his disabled daughter had softened his edges—here was a student of God’s Word who didn’t live in an ivory tower but in a real world with real pain.

I could wax on about Michael’s theological background, teaching experience, and degrees. But what I want you to mostly know about him is his zeal for Jesus Christ and his deep desire to reach families affected by disability with gospel hope—it’s why he’s helped us deliver wheelchairs around the world to needy disabled people, serving with us in Africa and Eastern Europe. As our ministry grew, I realized we needed someone like Mike to serve as a watchdog, helping to keep our theological underpinnings secure. So I asked him to serve on the International Board of Directors of Joni and Friends in 2000.

And I wish I could adequately express how happy I am about his new book, Disability and the Gospel, because there are thousands of families like the Beates family and millions of people like me whose disabilities force hard-hitting questions about God and the church:

What does a pastor say when disability hits a family in his congregation broadside? How do Christian education directors respond when autism becomes a serious matter in the classroom? How does the church get engaged with issues that impact our culture, like physician-assisted suicide? What does it take to get a congregation to recognize its weaker members as “indispensable”? In short, how do we grab the church by its shoulders and shake some sense into it about “glorying in our infirmities”?

This excellent resource by Michael Beates gives solid answers to tough questions like these and more. It is my heartfelt prayer that you will take the insights in Disability and the Gospel and use them as a guide and resource for your church family. And don’t be surprised if you see a sudden outbreak of heaven-sent power ripple through your life and the life of your congregation—for God’s power always shows up best in brokenness. And you don’t have to break your neck to believe it.

Readers also may want to be aware of a conference this fall at Bethlehem Baptist Church in Minneapolis: “The Works of God: God’s Good Design in Disability.” There is a great group of speakers: Nancy Guthrie, Mark Talbot, Greg Lucas, and John Piper.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers