Justin Taylor's Blog, page 196

August 20, 2012

“God Is Turning the World Upside Down that It May Be Right Side Up When Jesus Comes”

From a children’s book written over 100 years ago by husband-and-wife missionaries-to-Muslims Samuel and Amy Zwemer:

When you read in mission reports of troubles and opposition, of burning up books, imprisoning colporteurs and expelling missionaries you must not think that the gospel is being defeated.It is conquering.

What we see under such circumstances is only the dust in the wake of the ploughman.

God is turning the world upside down that it may be right side up when Jesus comes.

He that plougheth should plough in hope.

We may not be able to see a harvest yet in this country but, furrow after furrow, the soil is getting ready for the seed.

http://www.archive.org/stream/topsytu...

—Samuel M. Zwemer and Amy E. Zwemer, Topsy-Turvy Land: Arabia Pictured for Children (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1902), 116.

HT: Tim Keesee

Analogies, Thought Experiments, and the Creator-Creature Distinction

Following up on the previous post (my take on whether an all-powerful being is a moral monster if he can save all but doesn’t), the following might prove helpful and/or clarifying.

As I mentioned, many missteps in theology are on account of the implicit idea that God must be act as we would act. It is common among some to appeal to the image of God, our sense of moral intuition, and Jesus as the ultimate revelation of God to advance the idea that if we wouldn’t act in a certain way, then we know that God cannot act this way and remain righteous.

But I think that is inverting the proper Creator-creature relationship. A. B. Caneday has a thoughtful discussion on this point:

Apprehension of God and relation to God are ours only in terms of analogies that derive from the fact that God made man in his own image.

God’s imprinted image is organic.

The Creator-creature analogy yields the Bible’s five primary analogical relationships within which we relate to God:

(1) king and subject;

(2) judge and defendant/litigant;

(3) husband and wife;

(4) father and child; and

(5) master and slave.

God, who made his creatures in his own image, is pleased to disclose himself to us in keeping with the God-like adornment with which he clothed us.

Here is the essence of anthropomorphism. God reveals himself to us in human terms, yet we must not compare God to us as if we were the ultimate reference point. God organically and indelibly impressed his image upon man so that our relationships to one another reflect his relationships with us.

We do not come to know God as creator ex nihilo because we know ourselves to be creative and imagine him to be greater. Instead, man creates because we are like God. God is the original; we are the organic image, the living copy.

We do not rightly speak of God as king by projecting onto him regal imagery because we think it is fitting for God. Rather, bowing before God who has dominion is proper because man, as king over creation, is the image of kingship; God, the true king, is the reality that casts the image of the earthly king.

It is not as if God looked around his creation and found marital union between male and female to be a fit pattern for his relationship with humans. “Male and female he created them” that they may “become one flesh” (Gen. 2:24). The union of husband and wife is an earthly image or copy of the heavenly union of God, the true husband, with his people, the true bride. Paul understood marriage in Genesis 2:24 this way, for he cites the passage and explains, “This is a profound mystery—but I am talking about Christ and the church” (Eph. 5:32).

—A. B. Caneday, “Veiled Glory: God’s Self-Revelation in Human Likeness—A Biblical Theology of God’s Anthropomorphic Self-Disclosure,” in Beyond the Bounds, ed. Piper, Taylor, and Helseth (Crossway, 2003), p. 163; my emphasis. [The whole book is online for free.]

The great Princetonian theologian B. B. Warfield reflects on this when it comes to the issue of universalism. Fred Zaspel (The Theology of B. B. Warfield, pp. 418-419) summarizes:

Universalistic notions seem to be driven by the assumptions that God “owes” salvation equally to all men, that it would be unfair for him to favor a few, and that sin is not really sin deserving of wrath but rather misfortune deserving of pity—that is, a low view of sin.

Warfield illustrates the matter by comparing a doctor and a judge.

We might fault a doctor who, although able to relieve a sickness in all, actually relieves only some.

Yet we may wonder how a judge could release any guilty offender at all.

God in his love does pity and save, but he is righteous as well as loving. Accordingly, God in love saves only as many “as he can get the consent of his whole nature to save.” God “will not permit even his ineffable love to betray him into any action which is not right.”

We might sympathize with the “leveling” tendencies of politics—freedom for all, rights for all, education for all, and so on. The cry from a nation’s citizens to its government to give all “an equal chance” is one thing. But the turbulent self-assertion of convicted criminals demanding clemency is quite another.

We must fix it firmly in our minds, Warfield insists, that salvation is the right of no one and that a “chance” to save oneself is no chance of salvation for any, and that if anyone at all is saved, it must be by a miracle of divine grace on which no one has any claim whatever. All this is so designed that any who are saved can only be “filled with wondering adoration of the marvels of the inexplicable love of God.” Indeed, Warfield continues, “To demand that all criminals shall be given a ‘chance’ of escaping their penalties, and that all shall be given an ‘equal chance,’ is simply to mock at the very idea of justice, and no less, at the very idea of love.”

Is the God of Calvinism a Moral Monster?

The documentary Hellbound?—made by the same folks behind the documentary on intelligent design, Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed (starring Ben Stein)—premieres in September 2012.

Mark Driscoll, Kevin DeYoung, and I were among those interviewed for the film, though I suspect only Driscoll made the final cut. On the other side of the theological spectrum are folks like Edward Fudge, Greg Boyd, and Frank Schaeffer. Based on the early positive reviews by Boyd and Schaeffer, along with people like Phyllis Tickle and Brian McLaren, I don’t think it’s a mystery the direction the film is intended to lead viewers.

I would rather interview than be interviewed, but I like Kevin Miller and welcomed the opportunity for civil discourse with someone who didn’t share my beliefs.

In the clip below from our conversation (which is not in the film), you can see my on-the-fly attempt to respond to the charge that eternal punishment entails that God is a moral monster. If I had a “do over” I might have challenged the premise of the analogy: if a father can rescue his children from destruction but only saves some we consider him morally culpable, but in the Christian worldview we are rebelling against the Judge and receive a free offer of mercy which we reject. Instead, I focused on the underlying issue I see at play not only in this debate but in so many aspects of progressive revisionism: namely the desire to create God in our own image, to create a functional canon within a canon, to reason from the ground-up rather than the top-down, and to require that God’s authoritative revelation first meet with our approval.

Here is the trailer for the film:

For those wanting to read more on the biblical understanding of hell, here are a couple of books you should consider

Is Hell for Real or Does Everyone Go To Heaven? ed. Christopher Morgan and Robert Peterson (with contributions from Keller, Packer, Mohler, and others)

Hell on Trial: The Case for Eternal Punishment, by Robert Peterson.

Erasing Hell: What God Said about Eternity, and the Things We Made Up, by Francis Chan and Preston Sprinkle.

Christ Alone: An Evangelical Response to Rob Bell’s “Love Wins,” by Michael Wittmer.

August 17, 2012

“I’d Rather Be Slow to Learn Than Slow to Love”

Dear Pat Robertson:

August 16, 2012

The Difference between a Theologian of the Cross and a Theologian of Glory

Carl Trueman on “the most glorious contribution of Martin Luther to theological discourse,” first revealed in Heidelberg during a meeting in 1518:

At the heart of this new theology was the notion that God reveals himself under his opposite; or, to express this another way, God achieves his intended purposes by doing the exact opposite of that which humans might expect. The supreme example of this is the cross itself: God triumphs over sin and evil by allowing sin and evil to triumph (apparently) over him. His real strength is demonstrated through apparent weakness. This was the way a theologian of the cross thought about God.

The opposite to this was the theologian of glory. In simple terms, the theologian of glory assumed that there was basic continuity between the way the world is and the way God is: if strength is demonstrated through raw power on earth, then God’s strength must be the same, only extended to infinity. To such a theologian, the cross is simply foolishness, a piece of nonsense.

Trueman goes on to ask where the theologians of the cross are to be found today:

At this Reformation season, we should not reduce the insights of Luther simply to justification by grace through faith. In fact, this insight is itself inseparable from the notion of that of the theologians of the cross. Sad to say, it is often hard to discern where these theologians of the cross are to be found. Yes, many talk about the cross, but the cultural norms of many churches seem no different to the cultural norms of—well, the culture. They often indicate an attitude to power and influence that sees these things as directly related to size, market share, consumerist packaging, aesthetics, youth culture, media appearances, swagger and the all-round noise and pyrotechnics we associate with modern cinema rather than New Testament Christianity. These are surely more akin to what Luther would have regarded as symptomatic of the presence and influence of theologians of glory rather than the cross. An abstract theology of the cross can quite easily be packaged and marketed by a theologian of glory. And this is not to point the finger at `them’: in fact, if we are honest, most if not all of us feel the attraction of being theologians of glory. Not surprising, given that being a theologian of glory is the default position for fallen human nature.

The way to move from being a theologian of glory to a theologian of the cross is not an easy one, not simply a question of mastering techniques, reading books or learning a new vocabulary. It is repentance.

In another essay, Trueman writes:

This argument is explosive, giving a whole new understanding of Christian authority. Elders, for example, are not to be those renowned for throwing their weight around, for badgering others, and for using their position or wealth or credentials to enforce their own opinions. No, the truly Christian elder is the one who devotes his whole life to the painful, inconvenient, and humiliating service of others, for in so doing he demonstrates Christlike authority, the kind of authority that Christ himself demonstrated throughout his incarnate life and supremely on the cross at Calvary.

You can read both Trueman’s blog post and article.

See also Gerhard Forde’s On Being a Theologian of the Cross: Reflections on Luther’s Heidelberg Disputation, 1518 and Alister McGrath’s Luther’s Theology of the Cross: Martin Luther’s Theological Breakthrough.

August 14, 2012

More Important than Knowing God

J. I. Packer:

What matters supremely, therefore, is not, in the last analysis, the fact that I know God, but the larger fact which underlies it—the fact that he knows me. I am graven on the palms of his hands [Isa. 49:16]. I am never out of his mind. All my knowledge of him depends on his sustained initiative in knowing me. I know him because he first knew me, and continues to know me. He knows me as a friend, one who loves me; and there is no moment when his eye is off me, or his attention distracted from me, and no moment, therefore, when his care falters.

This is momentous knowledge. There is unspeakable comfort—the sort of comfort that energizes, be it said, not enervates—in knowing that God is constantly taking knowledge of me in love and watching over me for my good. There is tremendous relief in knowing that his love to me is utterly realistic, based at every point on prior knowledge of the worst about me, so that no discovery now can disillusion him about me, in the way I am so often disillusioned about myself, and quench his determination to bless me.

—Knowing God (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 41-42, emphasis added.

C. S. Lewis:

In the end that Face which is the delight or the terror of the universe must be turned upon each of us either with one expression or with the other, either conferring glory inexpressible or inflicting shame that can never be cured or disguised. I read in a periodical the other day that the fundamental thing is how we think of God. By God Himself, it is not! How God thinks of us is not only more important, but infinitely more important. Indeed, how we think of Him is of no importance except insofar as it is related to how He thinks of us. . . . To please God . . . to be a real ingredient in the Divine happiness . . . to be loved by God, not merely pitied, but delighted in as an artist delights in his work or a father in a son—it seems impossible, a weight or burden of glory which our thoughts can hardly sustain. But so it is.

—”The Weight of Glory,” in The Weight of Glory: And Other Addresses (orig., 1949; HarperCollins:2001), 39.

“But if anyone loves God, she is known by God.” (1 Cor. 8:3)

“On that day many will say to me, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many mighty works in your name?’ And then will I declare to them, ‘I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness.’” (Matt. 7:22-23)

“But now that you have come to know God, or rather to be known by God, how can you turn back again to the weak and worthless elementary principles of the world, whose slaves you want to be once more?” (Gal. 4:9)

August 12, 2012

Why We Still Haven’t Found What We’re Looking For

Blaise Pascal (1623-1662)

What else does this longing and helplessness proclaim, but that there was once in each person a true happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? We try to fill this in vain with everything around us, seeking in things that are not there the help we cannot find in those that are there. Yet none can change things, because this infinite abyss can only be filled with something that is infinite and unchanging—in other words, God himself. God alone is our true good.

—Pensées #425

C. S. Lewis:

If we are made for heaven, the desire for our proper place will be already in us, but not yet attached to the true object, and will even appear as the rival of that object. . . . If a transtemporal, transfinite good is our real destiny, then any other good on which our desire fixes must be in some degree fallacious, must bear at best only a symbolical relation to what will truly satisfy.

In speaking of this desire for our own far-off country, which we find in ourselves even now, I feel a certain shyness. I am almost committing an indecency. I am trying to rip open the inconsolable secret in each one of you—the secret which hurts so much that you take your revenge on it by calling it names like Nostalgia and Romanticism and Adolescence; the secret also which pierces with such sweetness that when, in very intimate conversation, the mention of it becomes imminent, we grow awkward and affect to laugh at ourselves; the secret we cannot hide and cannot tell, though we desire to do both.

We cannot tell it because it is a desire for something that has never actually appeared in our experience.

We cannot hide it because our experience is constantly suggesting it, and we betray ourselves like lovers at the mention of a name.

Our commonest expedient is to call it beauty and behave as if that had settled the matter. Wordsworth’s expedient was to identify it with certain moments in his own past. But all this is a cheat. If Wordsworth had gone back to those moments in the past, he would not have found the thing itself, but only the reminder of it; what he remembered would turn out to be itself a remembering. The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located will betray us if we trust to them; it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing. These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but if they are mistaken for the thing itself they turn into dumb idols, breaking the hearts of their worshippers. For they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

Do you think I am trying to weave a spell? Perhaps I am; but remember your fairy tales. Spells are used for breaking enchantments as well as for inducing them. And you and I have need of the strongest spell that can be found to wake us from the evil enchantment of worldliness which has been laid upon us for nearly a hundred years. Almost our whole education has been directed to silencing this shy, persistent, inner voice; almost all our modem philosophies have been devised to convince us that the good of man is to be found on this earth. And yet it is a remarkable thing that such philosophies of Progress or Creative Evolution themselves bear reluctant witness to the truth that our real goal is elsewhere. When they want to convince you that earth is your home, notice how they set about it.

They begin by trying to persuade you that earth can be made into heaven, thus giving a sop to your sense of exile in earth as it is.

Next, they tell you that this fortunate event is still a good way off in the future, thus giving a sop to your knowledge that the fatherland is not here and now.

Finally, lest your longing for the transtemporal should awake and spoil the whole affair, they use any rhetoric that comes to hand to keep out of your mind the recollection that even if all the happiness they promised could come to man on earth, yet still each generation would lose it by death, including the last generation of all, and the whole story would be nothing, not even a story, for ever and ever. . . .

Do what they will, then, we remain conscious of a desire which no natural happiness will satisfy. But is there any reason to suppose that reality offers any satisfaction to it? “Nor does the being hungry prove that we have bread.” But I think it may be urged that this misses the point. A man’s physical hunger does not prove that that man will get any bread; he may die of starvation on a raft in the Atlantic. But surely a man’s hunger does prove that he comes of a race which repairs its body by eating and inhabits a world where eatable substances exist.

In the same way, though I do not believe (I wish I did) that my desire for Paradise proves that I shall enjoy it, I think it a pretty good indication that such a thing exists and that some men will. A man may love a woman and not win her; but it would be very odd if the phenomenon called “falling in love” occurred in a sexless world.

C.S. Lewis, “The Weight of Glory” (1962)

August 10, 2012

Preaching in a Post-Everything World

On October 30-31, 2012, Southen Seminary will host The Expositors Summit, a preaching conference featuring Albert Mohler, John MacArthur, Russell Moore, and Alistair Begg. The theme is “Preaching in a Post-everything World.”

This annual conference sponsored by Southern’s National Center for Christian Preaching gathers preachers and seminary students to participate in a Christ-exalting, gospel-saturated, and Word-driven event.

In addition to the keynotes, there will be breakout seminars on the following topics:

Russell Moore, “A Christological Epicenter in Preaching”

Dan Dumas, “The Craft of Exposition”

Kevin Smith, “Getting Exposition Right so It Doesn’t Go Wrong”

Hershael York, “Transformational Expository Preaching”

Daniel Montgomery, “Communicating the Text”

The early bird rate available until September 10th is $179 for regular attendees. Reduced rates are available for students and alumni.

You can register or find out more here.

August 9, 2012

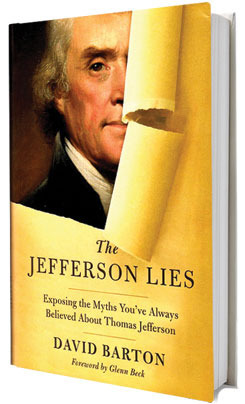

Thomas Nelson Ceases Publication of David Barton’s Error-Ridden Book on Jefferson’s Faith

The fine historian Thomas Kidd has been doing some excellent reporting work on the controversy surrounding David Barton’s book-length attempt to expose the “lies” and “myths” about Jefferson, his faith, his infidelity, and his view of slaves. The book has been promoted by Glenn Beck (who wrote the foreword), and Kirk Cameron featured Barton in his documentary Monumental.

The fine historian Thomas Kidd has been doing some excellent reporting work on the controversy surrounding David Barton’s book-length attempt to expose the “lies” and “myths” about Jefferson, his faith, his infidelity, and his view of slaves. The book has been promoted by Glenn Beck (who wrote the foreword), and Kirk Cameron featured Barton in his documentary Monumental.

Kidd reports that philosopher Jay Richards—who found the book to contain “embarrassing factual errors, suspiciously selective quotes, and highly misleading claims”—asked some conservative evangelical historians to examine the book’s claims.

Glenn Moots of Northwood University wrote that Barton in The Jefferson Lies is so eager to portray Jefferson as sympathetic to Christianity that he misses or omits obvious signs that Jefferson stood outside “orthodox, creedal, confessional Christianity.”

A second professor, Glenn Sunshine of Central Connecticut State University, said that Barton’s characterization of Jefferson’s religious views is “unsupportable.”

A third, Gregg Frazer of The Master’s College, evaluated Barton’s video America’s Godly Heritage and found many of its factual claims dubious, such as a statement that “52 of the 55 delegates at the Constitutional Convention were ‘orthodox, evangelical Christians.’” Barton told me he found that number in M.E. Bradford’s A Worthy Company.

There is even a book-length response just published:

A full-scale, newly published critique of Barton is coming from Professors Warren Throckmorton and Michael Coulter of Grove City College, a largely conservative Christian school in Pennsylvania. Their book Getting Jefferson Right: Fact Checking Claims about Our Third President (Salem Grove Press), argues that Barton “is guilty of taking statements and actions out of context and simplifying historical circumstances.” For example, they charge that Barton, in explaining why Jefferson did not free his slaves, “seriously misrepresents or misunderstands (or both) the legal environment related to slavery.”

Today Kidd reports that Thomas Nelson has decided to pull the book from publication.

The problems are not limited to a single book.

Political philosopher Greg Forster, an expert on John Locke, decided to take a look at one of Barton’s essays on Locke and found it to be filled with errors.

As historian John Fea points out, it appears that virtually no Christian colleges—conservative or otherwise—teach or endorse Barton’s revisionist views, though he is still very popular in some conservative Christian circles (especially in some, though of course not all, homeschooling networks).

This is actually a very interesting test case for those who have bought in to Barton’s historiography, methodology, and conclusions. Do we care about the truth, or do the conclusions we want to hear justify the means used to obtain them?

The Role of the Seminary in the World Today: Mohler and Lillback

Albert Mohler and Peter Lillback on the Christ the Center program (the conversation starts about 2 minutes in):

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers