Justin Taylor's Blog, page 192

September 11, 2012

Old Enough to Critique But Too Young to Parent

My students are often Christians who are old enough to mock mercilessly the people that gave of their time sacrificially to disciple them when they were young but who are not yet mature enough to be able to disciple others. I often find them quick-off-the-draw-ready with a forceful and sophisticated critique of most any traditional religious belief or practice.

They can be sadly flummoxed, however, by a simple request to explain what is true. If I wonder, “What are some problems with the doctrine of the atonement?” hands fly up all over the room, but if I straightforwardly ask, “What is the gospel?” the room falls strangely silent, and I find myself staring at rows of students quietly avoiding making eye contact.

To sketch what the gospel is would be to risk a rough draft that someone else would get the joy of critiquing; it would be to express a childlike faith; it would be to do the work of parenting.

You can read the whole thing here.

HT: Wesley Hill

September 10, 2012

Locating the Real Problem and the Real Solution

Al Mohler:

Most Americans believe that their major problem is something that has happened to them, and that their solution is to be found within. In other words, they believe that they have an alien problem that is to be resolved with an inner solution.

What they gospel says, however, is that we have an inner problem that demands an alien solution—a righteousness that is not our own.

—R. Albert Mohler Jr., “Preaching with the Culture in View,” in Preaching the Cross, Together for the Gospel (Wheaton, IL: Crossway 2007), p. 81.

HT: Dane Ortlund

How to Get a Do-It-Yourself MA in Political Philosophy

Greg Forster (PhD, Yale University)—an insightful thinker on American history, economics, and religion—is the author of Contested Public Square and Starting with Locke, as well as the editor of “Hang Together,” a new group blog on religion, politics, and national identity. I am grateful for his extensive recommended reading list below, which also functions as a nice overview of the big brush strokes of political philosophy. For those who are students and who are considering this as a field of study, I would recommend first reading Hunter Baker’s Political Thought: A Student’s Guide (which Forster himself reviewed here).

Back in 2005, Joe Carter asked readers of his blog to contribute their suggested reading lists for a “do it yourself MA” in their subject areas. I put one together for political philosophy and he was good enough to post it. Here it is, with only a few changes. Those who are interested may also want to take a peek at my book The Contested Public Square, which is an introduction to the history of Christianity and political philosophy.

Most political thought programs start with Hackett’s The Trial and Death of Socrates, which collects four dialogues of Plato (the Apology, the Euthyphro, the Crito, and the death scene from the Phaedo). This gives you an idea of (1) what philosophy is, and (2) why philosophy matters for the life of a political community.

Another good book to read at the outset, I think, would be G. K. Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man. While it is not explicitly a work of political philosophy, it gives you a really valuable insight on how philosophy relates to religion and how both of these affect the way political communities think and act. Chesterton understands philosophy, as practiced by the ancients, essentially as an alternative form of religion—the major alternative to pagan mythology. I think that’s basically right as far as the ancients go. On the other hand, the question of how Christianity relates to philosophy is a deep one with a long history, and this book at least raises it.

Then it’s time for the big plunge: Allan Bloom’s edition of Plato’s Republic. Make sure you get Bloom’s edition if you really want to read the book as Plato wrote it. Bloom’s interpretive essay is not required reading, but the textual notes in the back of the book are. I read this book with two bookmarks: one to keep my place in the main text and one in the endnotes, so I could keep flipping back as I went along. The notes are invaluable; they really should have been printed alongside the text, like a study Bible.

A common confusion about the Republic is that it is a plan for political reform. It is not that. Plato does not actually envision these proposals being enacted. Rather, the Republic is a meditation on the nature of human beings, specifically on what “justice” is. Why do human beings, alone among all natural creatures, believe that their affairs must be governed by rules of right and wrong? Plato thinks the answer lies in the way human psychology is constructed, and the “ideal” political community he sketches in the Republic is intended to illustrate this.

For extra credit, you might want to read Plato’s Laws (a set of practical observations on the laws of Greek communities), the Protagoras (on the sources of virtue), and the Symposium (on the sources of sexual love and the longing for eternity in the human soul).

Next up are Aristotle’s Ethics (sometimes called the Nicomachean Ethics in honor of Aristotle’s son Nicomachus, who collected and edited his father’s works for publication) and the Politics. I would recommend reading them in that order. Aristotle is such a precise and systematic writer that it doesn’t much matter which translation you use. If you find Aristotle to your taste, you might be interested in the Rhetoric as well, though it is a less profound book.

Pre-Christian Rome

Optionally, if you are interested in pre-Christian Rome, you might want to read the Republic of Cicero and the Reflections of Marcus Aurelius. But no one will think you any less well-informed if you skip them.

For a more lively portrait of political thought in Rome during its republican and imperial periods, read Shakespeare’s plays Coriolanus and Julius Caesar (for all Shakespeare plays I highly recommend The Complete Pelican Shakespeare). Getting your classical history from Shakespeare is cheating, but let me tell you, it works.

Roman Thought and Christianity

Roman Thought and Christianity

Now you have a pretty solid overview of political thought in the pre-Christian world. The next big step is the cataclysmic encounter between Roman thought (both its religion and its philosophy) and Christianity. If you really want to get the full story here, there’s no substitute for reading Augustine’s City of God. Yes, I know, it’s 1,100 pages long, but a lot of it is redundant and you have permission to skip whenever he starts belaboring a point. Make sure you get a modern translation (as opposed to the obsolete translations available on the Internet) in an annotated edition; Augustine spends a lot of time discussing things that were being said by other people, and you’re going to need footnotes to keep track.

As with the Republic, there is a common confusion to avoid here. The Latin term traditionally translated “city” in the phrase “city of God” does not really mean “city” so much as “community.” Augustine does not envision the city of God and its opposite, the city of man, as distinct political entities. They are social groupings that coexist within the larger political community of the city. To some extent they interpenetrate one another.

Fast forward to the Middle Ages. The usual practice is to condense this entire thousand-year period of history into the thought of one man: Thomas Aquinas. There is actually a tremendous variety of thought in the Middle Ages, but unfortunately for the most part only specialists ever discover it.

The single most important thing to get here is the development of the idea of “natural law,” that is, the idea that God has revealed a basic moral order to all human beings through reason and conscience. While this idea was present in Christian thought from the early church, and also in much non-Christian philosophy, it was the medieval church that developed the full-fledged doctrine as we know it today. In Aquinas’ Summa Theologica, in the “First Part of the Second Part,” read Questions 90-114. This section of the Summa is traditionally called the “Treatise on Law.” The influence of Aristotle, whose works had been recently reintroduced to the West after having been lost since ancient times, is clearly visible here.

For extra credit, you can read Defensor Pacis by Marsilius of Padua, a 14th century thinker who took natural law in a more radically liberating direction. If you’re really interested in learning the political philosophy of this period, get yourself a copy of Ewart Lewis’s Medieval Political Ideas; it’s out of print but you can get it on the Internet.

The Emergence of Modernity (1500s)

Now we come to the emergence of modernity in the 16th century. There are a lot of interrelated developments that happen at the same time. Here are the three most important developments within the political thought of the time, in no particular order:

1) Natural-law thought culminates in the idea of “natural rights,” that is, claims for certain kinds of political treatment (e.g. the protection of private property) to which a person is entitled under natural law. A history of how this idea emerged can be found in Brian Tierney’s The Idea of Natural Rights. While this is a history book rather than a work of political thought, it’s valuable because it establishes how “natural rights” grew out of “natural law” and remained an essentially religious concept. Lots of people have the wrong idea about this, associating rights-language with secularization.

2) The breakdown of political order in much of Europe in the early 16th century, coupled with widespread fear that Europe was on the verge of being conquered by the Ottoman Empire, leads many people to think that the decorous rationality of natural-law thought just doesn’t cut the mustard in a harsh, cruel, and wicked world. Some people began turning to what we would call more “realistic,” even cynical, accounts of how the world works. People who thought in these terms were looking for a set of ethical demands that would be less idealistic and demand less of people, and thus be easier to actually achieve in practice. Their mood could be expressed as: “We don’t care how many angels can dance on the head of a pin—give us something that will stop the wars and put food in people’s mouths.”

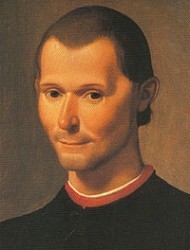

Machiavelli is the major thinker here; while most people were revolted by the open amoralism of his book The Prince, its critique of natural-law thought was nonetheless widely influential. You don’t have to go all the way down the road to amoralism to get Machiavelli’s major point, which is that all other questions will be moot if you fail to secure the safety of the political order, which (he argues) natural-law thought fails to do. For extra credit, read the Discourses on Livy.

Machiavelli is the major thinker here; while most people were revolted by the open amoralism of his book The Prince, its critique of natural-law thought was nonetheless widely influential. You don’t have to go all the way down the road to amoralism to get Machiavelli’s major point, which is that all other questions will be moot if you fail to secure the safety of the political order, which (he argues) natural-law thought fails to do. For extra credit, read the Discourses on Livy.

3) The Reformation fragments Europe into deeply hostile cultural groups. For a long time it was believed that Protestants and Catholics could not possibly share a common political community. The only thing for a ruler to do, it seemed, was to establish the dominance of one group and suppress or even completely stamp out the other group. A good summary statement of this kind of thinking can be found in Book IV, Chapter 20 of Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion; much the same was being said in reverse on the Catholic side. For an important dissenting view, see John Milton’s Areopagitica. Luther, interestingly, went back and forth on this question in a relatively short period; see the comparatively authoritarian Letter to the Christian Nobility of Germany and the (I think) comparatively libertarian Secular Authority: To What Extent It Should Be Obeyed.

While these currents in political thought were taking shape, the facts on the ground were changing in another way. The printing press (which drastically increased the use of popular languages rather than Latin), the fights over religion, and the increasing power of secular political authorities gradually led people to identify themselves more and more as members of larger political communities that we now call “nations.” It was during this period that people stopped thinking of themselves as Parisians or Nuremburgers or Londoners and started thinking of themselves as French or German or English. Over time, particularly in the 17th century, the boundaries of political units came to coincide with the nationalities of their peoples, producing the entity known as the “nation-state.”

How Should the Nation-State Be Governed?

From this time forward, the important question for political philosophy would become: how should the nation-state be governed?

The first really great political thinker whom you can unreservedly call “modern” is Thomas Hobbes. His Leviathan was written in reaction to the English Civil War, one of the bloodiest of the very bloody wars of religion that followed the Reformation. Hobbes wants to demystify politics—strip it of all religious and other transcendent associations—and make it into a science. If people would stop investing politics with so much religious, moral, and cultural importance, then they would stop killing each other so much. Hobbes is basically an opponent of religion; though he was careful to claim otherwise, his hostility to Christianity is obvious. Most of the arguments on the secularist side of our culture wars are ultimately rooted in a Hobbesian view of the world. Hobbes does borrow the language of “natural law” from Christian thought, but he twists it into a wholly new shape. Make sure you read both halves of Leviathan, not just the explicitly political first half; as you will see, the second half, which is a radically unorthodox interpretation of the Bible, is really just as important to what Hobbes is doing politically.

The next stop on our tour is John Locke, who also wrote in the context of England’s wars of religion (though during the Glorious Revolution of 1688 as opposed to the earlier Civil War). Locke takes two major currents of thought that had been developing particularly in English thought, and gave them their fullest and most forceful expression. The first is the idea that there is a “natural right” to armed resistance against tyranny, and the second is the idea of religious toleration. The key texts here are the Two Treatises of Government and the Letter Concerning Toleration. Locke’s formulation of these ideas was transformative. The whole idea of natural rights takes on a completely different character when one of those rights is the right to defend all your other rights by force, even against your own government. And no one needs to be told how transformative the idea of religious toleration was.

The idea of a right to resistance against tyranny was not new. It was actually the consensus view of almost all western political philosophy going back to the ancients. Christian natural law philosophy also held this view consistently throughout the Middle Ages. Locke lays out the reasons why: if there is no right to resistance against tyranny, ultimately you cannot sustain politics as a human activity distinct from the mere assertion of force. Citizenship is simply a form of slavery. And human reason and scripture alike make clear that political citizenship cannot be reduced to slavery.

However, Locke expressed this idea in a form that could be systematically implemented. Earlier thinkers left it in the background. Locke moved it to the forefront of social organization. Societies, Locke said, should make the right to rebellion one of their fundamental commitments, and lay out explicitly the boundaries beyond which government could not go without losing its legitimacy. In short, Locke institutionalized the right to rebellion.

There are two major confusions to avoid in reading the Two Treatises. First, Locke makes use of the idea of a “state of nature,” which was a sort of thought experiment that earlier political philosophers used to work out what the ultimate justification of government was. Hobbes was one of the earlier thinkers who used this method, but this does not mean Locke is following Hobbes’s thought. The concept of a “state of nature” was around in the Middle Ages and Locke’s use of it follows the trail laid down by Christian natural-law thought.

For Hobbes, there are no moral laws in the state of nature, and that’s why we have society; we fear our neighbors and want to restrain them. For Locke, there are moral laws in the state of nature, and that’s why we have society; we have a moral imperative to seek out a better enforcement of the moral law, so we create society to do so. Hobbes’s view gives us a universe where all morality is socially constructed for materialistic motives; Locke’s gives us a universe where moral law is the first and fundamental social reality, more basic even than society itself.

The other confusion to avoid when reading Locke is to think that the idea of a “divine right of kings,” which Locke argues against in the First Treatise, was the longstanding traditional political theory of Europe. This is simply a myth. Divine right theory was a radical innovation introduced by power-hungry monarchs in the early modern period. At a time when kings were getting a lot more powerful than they used to be, some of them got greedy and tried to promote the idea that the king speaks with God’s direct authority. But this view was never the mainstream or majority view of the West; the mainstream view (as in Aquinas) was always that the king got his authority as a grant from the community.

Locke’s thought was the beginning of what came to be called political “liberalism.” This is not the same sense in which that word is used in modern American politics (where “liberalism” is the opposite of “conservatism”) or in theology. Sometimes this ideology is called “classical liberalism.”

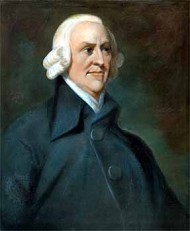

Two more major developments are necessary to get a complete introductory portrait of classical liberalism. First, for the economic thought that was a crucial element of liberalism, read Books I, III, and V of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. Don’t miss the intriguing analysis in Book V of how the behavior of schools and churches is shaped by financial incentives. If you’re interested in the issue of trade you might also want to read Book IV.

Two more major developments are necessary to get a complete introductory portrait of classical liberalism. First, for the economic thought that was a crucial element of liberalism, read Books I, III, and V of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. Don’t miss the intriguing analysis in Book V of how the behavior of schools and churches is shaped by financial incentives. If you’re interested in the issue of trade you might also want to read Book IV.

The other major element in classical liberalism is the development of what we might call “constitutional thought”—the working out what kinds of political institutions would best put liberalism into practice. One of the distinguishing characteristics of liberalism is its particular attention to the design of institutions. The Federalist Papers provide a concise statement of the basic elements of liberal constitutional thought; if you’re looking for more, you might want to tackle Baron Charles de Montesquieu’s much longer The Spirit of the Laws.

Classical Liberalism v. Its Critics

Classical liberalism has been the dominant mode of political thought since its emergence. The rest of the history of political philosophy is basically the story of classical liberalism versus its critics.

The first really large-scale reaction against liberalism was Romanticism, which had its origins almost entirely from the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It’s very hard to summarize Romanticism, but a good beginning of a summary is that seeks to replace theistic natural law with a deistic moral system built on subjective moral intuitions—”the conscience” understood as something separate from reason and not really subject to rational argumentation. For me the real heart of Rousseau’s works has always been the book Emile, which is sort of Rousseau’s version of Plato’s Republic. But it is more common for people to read his “Discourse on the Arts and Sciences” (also known as the “First Discourse”), “Discourse on the Origins of Inequality” (a.k.a. the “Second Discourse”), and especially his book The Social Contract, which is as close as he came to laying out a political program. For extra credit, American Romantics included Thomas Jefferson and Ralph Waldo Emerson (start with the essay “Self-Reliance“).

Political Traditionalism

Another major reaction against liberalism is what we might call political traditionalism. This bursts on the scene rather dramatically with Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. For extra credit, read Michael Oakeshott’s Radicalism in Politics and Other Essays and Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind.

Still another is utilitarianism. The hard-core version of utilitarianism was a passing intellectual phase in the 19th century that gained little traction. However, John Stuart Mill produced a more moderate version of utilitarianism that continues to be influential to this day. Start with the short book On Liberty; for extra credit read Utilitarianism. Mill’s most enduring idea is that people with ideas or ways of life that are unusual or unpopular need special protection against the overbearing pressure for conformity; here we find another major precursor of the secularist side of the culture war.

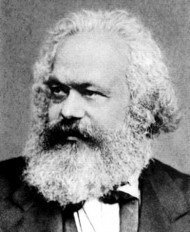

Marxism

Tempted as we may be, we can’t leave out Marxism. Only the Communist Manifesto is required reading as far as primary sources go; the basic ideas of Marxism are already too familiar, and are turning out not to be lasting very long historically anyway. But two major analyses of Marxism and its weaknesses are definitely required reading, especially since they are important for more than just their analyses of Marxism: George Orwell’s 1984 and Vaclav Havel’s The Power of the Powerless. Havel, particularly, diagnosed Marxism’s fundamental immorality as the fatal flaw that would ultimately bring it down. Extra credit assignments include Orwell’s Animal Farm and “Politics and the English Language,” and Havel’s play “The Memorandum.”

Tempted as we may be, we can’t leave out Marxism. Only the Communist Manifesto is required reading as far as primary sources go; the basic ideas of Marxism are already too familiar, and are turning out not to be lasting very long historically anyway. But two major analyses of Marxism and its weaknesses are definitely required reading, especially since they are important for more than just their analyses of Marxism: George Orwell’s 1984 and Vaclav Havel’s The Power of the Powerless. Havel, particularly, diagnosed Marxism’s fundamental immorality as the fatal flaw that would ultimately bring it down. Extra credit assignments include Orwell’s Animal Farm and “Politics and the English Language,” and Havel’s play “The Memorandum.”

The Most Powerful Critiques of Classical Liberalism

I’ve saved the most powerful critique of classical liberalism for last. Quite a few people who share very little else in common believe that classical liberalism can’t work because it leads people to want nothing more than lives of comfort and conformity, for which they are eventually willing to sell their freedom, their minds, and their souls.

Get ready, because I’m about to drop a pretty lengthy reading list on you: Alexis de Tocqueville’s huge but indispensable Democracy in America, Friedrich Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and C. S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man and “Screwtape Proposes a Toast.” See also Havel’s play “The Unveiling” and his essay “A Sense of the Transcendent.”

A New and Better Version of Classical Liberalism

In spite of all these critiques, in my opinion we shouldn’t be thinking in terms of replacing classical liberalism, but in terms of correcting its weak points and trying to make it work. At its heart, liberalism is a commitment to a social order based on religious freedom and giving people stewardship over their own lives; it’s an attempt to steer a course between the cynical power politics of Machiavelli and Hobbes on the one hand, and the unjust social hierarchies and enforced orthodoxies of premodern and traditionalist systems. I like to say classical liberalism boils down to four things:

the right to choose your church,

the right to choose your spouse,

the right to choose your job, and

the right to choose your rulers.

We had none of those rights before the rise of classical liberalism, and none of the major alternatives to liberalism would retain them. If you want to be able to make these choices for yourself—to have stewardship over your own life—then ultimately you’re going to be a liberal of some kind. The path forward, to my mind, is not a path away from classical liberalism but a path to a new and better kind of liberalism. For those who are interested, I’ve written about this in Contested Public Square and Starting with Locke.

Battling Depression

A couple of short video clips from counselor Ed Welch:

And in this video Welch shares a little bit of his own story as his father struggled with depression:

Some other resources that may be helpful:

Ed Welch, Depression: Looking Up from the Stubborn Darkness (revised edition)

Ed Welch, Depression: The Way Up When You Are Down (booklet)

David Murray, Christians Get Depressed Too

John Piper, When the Darkness Will Not Lift: Doing What We Can While We Wait for God—and Joy

Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Spiritual Depression: Its Causes and Cure

“Depression and the Ministry” (blog series by BCC & TGC)

For those in ministry, the writings by and about Charles Spurgeon on depression may be particularly valuable:

Charles Spurgeon, “The Minister’s Fainting Fits” in Lectures to My Students

Darrel W. Amundsen, “The Anguish and Agonies of Charles Spurgeon“

Zack Eswine, “Listening for the Sound of Reality: The Melancholy of Abraham Lincoln and Charles Haddon Spurgeon“

John Piper, “Charles Spurgeon: Preaching through Adversity“

Randy Alcorn on how Spurgeon’s writings on depression helped him go through his own depression in 2007 (part 1, part 2, part 3)

What Is the Theme of the First Five Books of the Bible?

To my mind, one of the most valuable features of the ESV Study Bible (and other study Bibles) are the introductions. The notes on individual verses are great, but interpretation will still go awry if we don’t understand the book’s genre and author and audience and timeframe and purpose. It’s also helpful to take a step back and to have concise introductions on some of the larger categories of the scriptural storyline: the Pentateuch (the first five books), the historical books, the poetic and wisdom books, the prophetic books, the Gospels and Acts, the epistles, and Revelation.

To my mind, one of the most valuable features of the ESV Study Bible (and other study Bibles) are the introductions. The notes on individual verses are great, but interpretation will still go awry if we don’t understand the book’s genre and author and audience and timeframe and purpose. It’s also helpful to take a step back and to have concise introductions on some of the larger categories of the scriptural storyline: the Pentateuch (the first five books), the historical books, the poetic and wisdom books, the prophetic books, the Gospels and Acts, the epistles, and Revelation.

These ESVSB genre introductions and more are included in the book Understanding the Big Picture of the Bible: A Guide to Reading the Bible Well, ed. Grudem, Collins, and Schreiner.

Here is one of the sections from Gordon Wenham’s contribution.

The theme of the Pentateuch is announced in Genesis 12:1-3, the call of Abraham:

“Go from your country . . . to the land that I will show you. And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you . . . and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”

Here God promises Abraham four things:

(1) a land to live in;

(2) numerous descendants (“a great nation”);

(3) blessing (divinely granted success) for himself; and

(4) blessing through him for all the nations of the world.

God’s benefit for the nations is the climax or goal of the promises: the preceding promises of land, descendants, and personal blessing are steps on the way to the final goal of universal blessing.

Each time God appears to the patriarchs, the promises are elaborated and made more specific. For example, the promise of an unidentified “land” in Genesis 12:1 becomes “this land” in Genesis 12:7 and “all the land of Canaan, for an everlasting possession” in Genesis 17:8.

The fulfillment of these promises to Abraham constitutes the story line of the Pentateuch.

It is a story of gradual and often difficult fulfillment.

The birth of children to produce a great nation is no easy matter: the patriarchs’ wives—Sarah, Rebekah, and Rachel—all have great trouble conceiving (Gen. 17:17; 25:21; 30:1). But by the time they enter Egypt, Jacob’s family numbers 70 (Gen. 46:27; Ex. 1:5). After many years in Egypt they have become so numerous that the Egyptians perceive them as a threat (Ex. 1:7-10), and when the first census is taken, they total 603,550 fighting men (Num. 1:46).

Similarly the promise of land is very slow in being fulfilled. Abraham acquires a well at Beersheba, and a burial plot for Sarah at Hebron (Gen. 21:30-31; 23:1-20). Jacob bought some land near Shechem (Gen. 33:19), but then late in life he and the rest of the family emigrated to Egypt (Genesis 46-50). The book of Exodus begins with the hope of a quick return to Canaan, but the stubbornness of Pharaoh delays Israel’s departure. Their journey through the Sinai wilderness is eventful, and after about a year they reach Kadesh on the very borders of Canaan. There, scared by the report of some of the spies, the people rebel against Moses and the God-given promises, so they are condemned to wander in the wilderness for 40 years (Numbers 13-14). And of course the Pentateuch ends with Moses dying outside the Promised Land and the people hoping to enter it.

For these reasons the theme of the Pentateuch has been described as “the partial fulfillment of the promises to the patriarchs.” Such a description certainly fits the climactic promise that through Abraham and his descendants all the families of the earth would be blessed. The closest fulfillment of this in the Pentateuch is Joseph saving Egypt and the surrounding lands from starvation in the seven-year famine. But later on, Israel is seen as a threat by other peoples in the region such as the Moabites, Midianites, and Amorites. It is not apparent how or when all the peoples of the world will be blessed. At the end of the Pentateuch that, like the promise of land, still awaits fulfillment.

But the promise of blessing to the patriarchs and their descendants is abundantly fulfilled within the Pentateuch—despite their frequent lack of faith and their willful rebellion. For example, after Abraham has lied about his wife and allowed her to be taken by a foreign king, the pair escape, greatly enriched (Genesis 12; 20). Jacob, forced to flee from home after cheating his father, eventually returns with great flocks and herds to meet a forgiving brother (Genesis 27-33). The nation of Israel breaks the first two commandments by making the golden calf, yet enjoys the privilege of God dwelling among them in the tabernacle (Exodus 32-40). The Pentateuch is thus a story of divine mercy to a wayward people.

However, alongside this account of God’s grace must be set the importance of the law and right behavior. The opening chapters of Genesis set out the pattern of life that everyone should follow: monogamy, Sabbath observance, rejection of personal vengeance and violence—principles that even foreigners living in ancient Israel were expected to observe. But Israel was chosen to mediate between God and the nations and to demonstrate in finer detail what God expected of human society, so that other peoples would exclaim, “What great nation has a god so near to it . . . ? And what great nation is there, that has statutes and rules so righteous as all this law . . . ?” (Deut. 4:7-8).

To encourage Israel’s compliance with all the law revealed at Sinai, it was embedded in a covenant. This involved Israel giving its assent to the Ten Commandments and the other laws on worship, personal behavior, crime, and so on. Obedience to these laws guaranteed Israel’s future blessing and prosperity, whereas disobedience would be punished by crop failure, infertility, loss of God’s presence, defeat by enemies, and eventually exile to a foreign land (see Leviticus 26; Deuteronomy 28).

These covenantal principles—that God will bless Israel when she keeps the law and punish her when she does not—pervade the rest of the OT. The book of Joshua demonstrates that fidelity to the law led to the successful conquest of the land, while the books of Judges and Kings show that Israel’s apostasy to other gods led to defeat by her enemies. The argument of the prophets is essentially that Israel’s failure to keep the law puts her at risk of experiencing the divine punishments set out in Leviticus 26 and Deuteronomy 28.

From NT times, Christians have seen the promises in the Pentateuch as finding their ultimate fulfillment in Christ.

Jesus is the offspring of the woman who bruises the serpent’s head (Gen. 3:15).

He is the one through whom “all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Gen. 12:3).

He is the star and scepter who shall rise out of Israel (Num. 24:17).

More than this, many heroes of the OT have been seen as types of Christ.

Jesus is the second Adam.

He is the true Israel (Jacob), whose life sums up the experience of the nation.

But preeminently Jesus is seen as the new and greater Moses. As Moses declared God’s law for Israel, so Jesus declares and embodies God’s word to the nations. As Moses suffered and died outside the land so that his people could enter it, so the Son of God died on earth so that his people might enter heaven. It was observed that the filling of the tabernacle with the glory of God was the climax of the Pentateuch (Ex. 40:34-38). So too “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen his glory” (John 1:14).

The goal of the entire Bible is that humans everywhere should glorify the God whose glory has confronted them. Lost sight of in Eden, this goal reappears through Moses, on its way to final fulfillment through Christ.

September 7, 2012

Why You Should Really Consider This 30-Year-Old Book: Keller, Powlison, and Ortlund

Richard Lovelace’s The Dynamics of Spiritual Life: An Evangelical Theology of Renewal (IVP, 1979) is a unique work. I know of nothing like it. Once you finish it you will feel like you’ve read at least three books. If you agree with everything in it, you are likely a bit eccentric. But every page—agree or disagree—is worth wrestling with.

Richard Lovelace’s The Dynamics of Spiritual Life: An Evangelical Theology of Renewal (IVP, 1979) is a unique work. I know of nothing like it. Once you finish it you will feel like you’ve read at least three books. If you agree with everything in it, you are likely a bit eccentric. But every page—agree or disagree—is worth wrestling with.

I asked three brothers who have been influenced by the book—Tim Keller, David Powlison, and Ray Ortlund—if they would share how the book has influenced their own lives.

Tim Keller:

I took several courses with Richard Lovelace at Gordon-Conwell Seminary, including the first course “Dynamics of Spiritual Life” in Fall of 1972 that eventually became Lovelace’s book. Along with that course I also took a course he did on Evangelical Awakenings–a history of revivals. To say that these courses were seminal to my thinking and way of doing ministry is a pretty big understatement. Anyone who knows my ministry and reads this book will say, “So that’s where Keller got all this stuff!”

Twenty-five years ago, when church planters came to me and asked me “what should I read?” I always gave them two books–Lovelace’s Dynamics of Spiritual Life and Michael Green’s Evangelism through the Local Church. The former gave them a way of using the gospel in people’s lives that not only brought them to saving faith but also kept renewing them individually and corporately. The Green book was a practical how-to book on getting that gospel out in a hundred different ways. Dynamics of Spiritual Life is somewhat long and a bit repetitious–but it’s still a book that I think we can’t do without. It was amazingly prescient and will be found still quite relevant to many of today’s debates.

David Powlison:

There is nothing quite like learning from a church historian who really cares about the outcome of the church’s history—who wants to shape what could happen, not just study what did happen. Richard Lovelace, who formerly taught at Gordon-Conwell Seminary, is just such a pastoral historian. With good reason, his Dynamics of the Spiritual Life is still in print after 30+ years, whereas many current best-sellers will be forgotten by next year.

I read this book multiple times in the 1980s. Though I’ve not reread it since, I still cite from memory many significant Lovelace insights: “characteristic flesh,” “the sanctification gap,” “n-step sanctification,” “the need for a tuned and adapted form of nouthetic counseling.” We all gain from his wisdom on the interrelationship of individual and corporate sanctification, and on the relationship between justification and sanctification.

Lovelace’s breadth of knowledge and judicious sense for “We’ve seen that before” can shape wise ministries able to combine both earnestness and patience, able to combine the right kind of enthusiasm with the right kind of caution. Of course, some of his examples are dated, and you may not always draw the same conclusions he did. But Lovelace’s sense for how Christian wisdom balances many complementary emphases is worth more than gold.

Ray Ortlund:

Dynamics of Spiritual Life by Richard Lovelace is rarely far from my thoughts. The same is true for certain works by Jonathan Edwards, Francis Schaeffer and my dad. These writers have shaped how I see the gospel, life and ministry at a level as deep as perception itself.

Lovelace’s Preface defines his book as “a manual of spiritual theology”—in my view, a rare and precious genre. On page 58 he boldly asserts that “virtually all of the problems in the church, including bad theology, issue from defective spirituality.” I wonder what you think of that. My hunch is, some of us doubt that analysis. But I get ahead of myself. Lovelace’s Table of Contents alone deserves thoughtful contemplation. (Page 75 reproduces this outline in briefly expanded form.) It sets a compelling agenda for pastoring and church planting.

In the first 200 pages, Part One, “Dynamics of Renewal,” Lovelace proposes convictions for shaping a church as revival-ready:

Chapter 1: Jonathan Edwards and the Jesus Movement

Originally published in 1979, DOSL uses the Jesus Movement of that decade as its immediate context. Today this seems dated. I hope you won’t be put off by that. Although DOSL is situated in that moment, it remains relevant because of the broad historical survey of renewal movements this chapter offers, with the various models of revival proposed along the way.

Highlight :

“The leaders and shapers of the Reformation, the Puritan and Pietist movements, and the first two awakenings, included trained theologians who combined spiritual urgency with profound learning, men who had mastered the culture of their time and were in command of the instruments needed to destroy its idols and subdue its innovations” (page 49).

Chapter 2: Biblical Models of Cyclical and Continuous Renewal

Lovelace notes the cyclical history of Israel rising and declining in the Old Testament, compared with the continuous renewal of the church in the book of Acts. But why, as New Covenant people today, do we seem to resemble the unstable patterns of the Old Covenant people of God? Is there a theologically responsible, non-mechanistic way to structure our pursuit of gospel spirituality today so as to press more fruitfully into our union with Christ? This brief chapter sets up Lovelace’s following proposals.

Chapter 3: Preconditions of Continuous Renewal

There are two essentials in a church environment for renewal to get traction: (1) clarity about who God really is, and (2) clarity about who we really are.

Highlights:

“What men wake up to in the light of a revival is their own condition and the nature of the true God” (page 82). “Many American congregations were in effect paying their ministers to protect them from the real God” (page 84). “The apprehension of God’s presence is the ultimate core of genuine Christian experience” (page 85).

“. . . even [man's] virtues are organized as weapons against the rule of God” (page 86).

“Luther was right: the root behind all other manifestations of sin is compulsive unbelief” (page 90).

“Modern man is not immune to the impact of traditional Christian terminology; he is simply inert in the presence of answers to questions he has not yet been induced to ask” (page 92).

Chapter 4: Primary Elements of Continuous Renewal: Depth Penetration of the Gospel

Our union with Christ brings to us powers for renewal through (1) justification, (2) sanctification, (3) the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, and (4) authority in spiritual conflict. Lovelace is brilliant, in my opinion, in his fresh articulation of the reviving powers we can experience as the gospel is pressed into us deeply and regularly.

Highlights:

“In order for a pure and lasting work of spiritual renewal to take place within the church, multitudes within it must be led to build their lives on this foundation [i.e., acceptance in Christ alone, apart from our performance]” (pages 101-102).

“The Protestant disease of cheap grace can produce some of the most selfish and contentious leaders and lay people on earth, more difficult to bear in a state of grace than they would be in a state of nature” (pages 103-104).

“Luther too recognized its validity [i.e., Roman Catholic awareness of Satan] and conceived of his work as an assault against the entrenched powers of hell within the church.” “It takes time, and the penetration of truth, to make a mature saint” (page 143).

Chapter 5: Secondary Elements in Renewal: Outworking of the Gospel in the Church’s Life

The great and primary powers of the gospel prove themselves in a church’s experience through (1) orientation toward mission, (2) dependent prayer, (3) believers in community, (4) theological integration and (5) disenculturation. By “disenculturation,” Lovelace means the objectivity that can disentangle the essential realities of Christianity from the particular cultural forms it takes in one’s own church. With this more mature outlook, we are freer to spread the gospel in its purity and power – uncomplicated, simple, rust-free.

Highlights:

“Converts are won more by the observable blessedness of a whole way of life than by the arguments of individuals” (page 148).

“Our fallen nature is actually allergic to God and never wants to get too close to him. Thus our fallen nature constantly pulls us away from prayer” (page 155).

“As pain tells us of the need for healing, worry tells us of the need for prayer” (page 160).

“In our quest for the fullness of the Spirit, we have sometimes forgotten that a Spirit-filled intelligence is one of the powerful weapons for pulling down satanic strongholds” (page 183).

“When men’s hearts are not full of God, they become full of the world around like a sponge full of clear water that has been squeezed empty and thrown into a mud puddle” (page 184).

Richard Lovelace’s Dynamics of Spiritual Life offers clear convictions and compelling priorities to shape our churches for revival in our time. I know of no other work with such potential impact.

In 1985 Lovelace also published a simplified version of DOSL entitled Renewal as a Way of Life, with discussion questions. It would be a powerful tool for a whole church to use in small groups when ramping up for a new era of gospel advance.

What the Puritans Can Teach Us about Counseling

Nearly 25 years ago, Tim Keller argued that the works of the Puritans are a rich resource for biblical counseling for the following six reasons:

Nearly 25 years ago, Tim Keller argued that the works of the Puritans are a rich resource for biblical counseling for the following six reasons:

The Puritans were committed to the functional authority of the Scripture. For them it was the comprehensive manual for dealing with all problems of the heart.

The Puritans developed a sophisticated and sensitive system of diagnosis for personal problems, distinguishing a variety of physical, spiritual, tempermental and demonic causes.

The Puritans developed a remarkable balance in their treatment because they were not invested in any one ‘personality theory’ other than biblical teaching about the heart.

The Puritans were realistic about difficulties of the Christian life, especially conflicts with remaining, indwelling sin.

The Puritans looked not just at behavior but at underlying root motives and desires. Man is a worshipper; all problems grow out of ‘sinful imagination’ or idol manufacturing.

The Puritans considered the essential spiritual remedy to be belief in the gospel, used in both repentance and the development of proper self-understanding.

To see each of these points unpacked in some depth, see Tim Keller, “Puritan Resources for Biblical Counseling,” The Journal of Pastoral Practice, vol. 9, no. 3 (1988): 11-44. (The journal is now named The Journal for Biblical Counseling.)

See also the book by Mark Deckard, Helpful Truth in Past Places: The Puritan Practice of Biblical Counseling (Christians Focus, 2010). The introduction, “New Is Not Necessarily Better,” can be read online for free. Deckard takes six questions that people struggle with, and uses a classic Puritan work to help us answer it:

Why is this happening to me? (John Flavel, The Mystery of Providence)

Why am I so anxious and dissatisfied? (Jeremiah Burroughs, The Rare Jewel of Christian Contentment )

What does sin have to do with my problem? (John Owen, On the Mortification of Sin in Believers )

Why doesn’t anyone understand my problems? (John Bunyan, Pilgrim’s Progress )

Don’t I need just to stop feeling? (Jonathan Edwards, The Religious Affections )

How can I find joy again? (William Bridge, A Lifting Up for the Downcast )

September 6, 2012

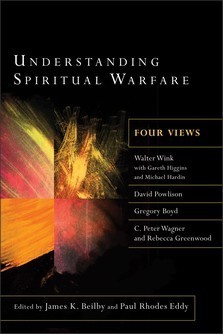

How Should We Think about Spiritual Warfare?

In December Baker Academic will publish a book entitled Understanding Spiritual Warfare: Four Views, edited by James Beilby and Paul Eddy. The contributors were asked to address five questions:

In December Baker Academic will publish a book entitled Understanding Spiritual Warfare: Four Views, edited by James Beilby and Paul Eddy. The contributors were asked to address five questions:

What is the nature of Satan and the demonic?

What role does spiritual warfare serve in the Bible and how central is it to the biblical narrative?

How should Christians conceive of and practice spiritual warfare?

Can individual human beings be “demonized”? If so, how does this happen and how is it to be dealt with? Can a Christian be demonized?

Do “territorial spirits” exist? If so, are we called directly to engage them in “strategic level” spiritual warfare?

The contributors and their titles are as follows:

The World Systems Model, by Walter Wink, edited by Gareth Higgins and Michael Hardin

The Classical Model, by David Powlison

The Ground-Level Deliverance Model, by Gregory Boyd

The Strategic-Level Deliverance Model, by C. Peter Wagner and Rebecca Greenwood

Several years ago I read David Powlison’s book, Power Encounters: Reclaiming Spiritual Warfare. (Sadly, no longer in print—though I have heard that a second edition may be forthcoming.) I found it both clarifying and persuasive.

Here are the notes I took in case you would find them helpful.

Reclaiming: Spiritual Warfare

“A great deal of fiction, superstition, fantasy, nonsense, nuttiness, and downright heresy flourishes in the church under the guise of ‘spiritual warfare’ in our time. . . . But the warfare we need to wage engages and implicates our humanity, rather than bypassing it for a superspiritual, demonic realm.”

Reasons for the Urgency

We live in a society where the modern agenda has largely failed.

We live in a society that has become increasingly pagan.

Missions, anthropology, and modern communications make us aware of the practices and beliefs of animistic cultures.

We live in a society of high-profile bondage to “addictions.”

Bizarre or troubled behavior, often related to experiences of extreme abuse, seems to be appearing more frequently.

Many people have sometimes experienced an uncanny, heightened sense of the presence of evil.

A growing number of Christians teach and practice “deliverance” ministry in the quest to cast out inhabiting demons.

Powlison’s Intentions

Truly all Christians believe in spiritual warfare; we all believe that Christ delivers us from evil. Powlison seeks to answer two crucial points of confrontation regarding spiritual warfare.

The first question engages how we understand the Christian life. What are we fighting? How does the evil one actually work? How does he exert—or attempt to exert—his dominion?

The second question engages our practice of the Christian life. How should we fight? What is the way God delivers us—and tells us to deliver ourselves and each other—from bondage to the devil? What is the mode of warfare?

Our Common Ground

The large majority of Christians give assent to four propositions, whatever our other differences.

We are involved in spiritual warfare.

Jesus Christ is the triumphant Deliverer and King.

The modern age deadens people to the reality of spiritual warfare.

Errors and excesses occur in deliverance ministries.

If deadly rationalism saps spiritual vitality on the one hand, the exorcistic mentality spawns mutant spiritualities on the other. Both the disenchanted world of modern rationalism and the charmed world of premodern spiritism are wrong.

What Is Spiritual Warfare?

Three competing visions vie for our allegiance:

Capitulation to the spirit of the age by radically reinterpreting the Bible’s “spirit” realities as mythical projections of psychological, sociological, political, and medical phenomena. (Inadequate for all serious followers of Christ.)

The demon deliverance ministries

The “classic” Christian mode of spiritual warfare

The “Ekballistic Mode” [EMM] of Spiritual Warfare

An invented term to describe the demon-deliverance movement that might seem awkward at first. It is a grassroots practical theology that finds varied expression both in pastoral ministry and in methods of personal growth. It envisions the warfare of Christians as a battle against invading demons, either to repel them at the gates or eject them after they have taken up residence. Obviously based on the key assumption that demons of sin reside within the human heart.

The “Classic Mode” of Spiritual Warfare

Evangelism, discipleship, and personal growth. Follows the pattern of Jesus facing Satan in the desert. The textbooks are the Psalms and Proverbs, the ways that Jesus addressed moral evil, and the teachings of the NT epistles.

EMM’s Strengths

They recognize and challenge the spiritual barrenness—the practical atheism—of the secular modern age.

They encourage conservative Christians to reenvision the world as a spiritual place so that the fight for Christ’s kingdom and glory might be more effective.

They challenge the notion that people’s personal problems can be reduced to purely psychological, social, physiological, or circumstantial factors.

Many “spiritual warriors” demonstrate admirable love and self-sacrifice.

They show that prayer matters.

They usually believe and practice classic-mode spiritual warfare much of the time.

Cultures Dark with the Occult

There are three important features of the occult worldview and its degraded existence.

Demonological explanations for all events and actions—good or bad—predominated.

Occult idolatry and practices were the norm.

Nations that practiced the occult also pursued other generic addictions, such as gluttony, drunkenness, varied forms of immorality, greed, blood thirst, and power.

All the contemporary “causes” are in place in the OT, but the Scriptures never identify or address spirit inhabitants as the problem nor cast them out as the solution. The OT, as a voice into these demon-filled cultures, exhibits two striking features.

It minimizes Satan.

The OT maximizes human responsibility.

Lifting the Curtain

Every so often in the OT God lifts the curtain to show the spirit realities at work behind the scenes. Six major passages:

Genesis 3:1-15

1 Samuel 16:13-23

1 Samuel 28:3-25

1 Kings 22:6-28

Job 1:6-2:10

Zechariah 3

God’s Sovereignty in an Evil World

God uses evil for his glory and the comfort of God’s people. EMM advocates simply do not articulate this understanding of God’s sovereignty in the mist of evil. Consequently, their understanding of spiritual warfare becomes skewed. The demons become increasingly autonomous; sin becomes demonized; the world gains the look and feel of superstition rather than biblical wisdom. EMM advocates rightly seek to reestablish a worldview that recognizes spirit beings, both good and evil. But the drift in EMM thinking toward demonological explanations creates a world more precarious and spooky than the Bible’s world. Ironically, in the end, the EMM worldview has more affinities with the occult worldview than the Bible.

The Bible gives an opposite, theocentric explanation. There the love of God—love for his name’s glory and his people’s welcome—strikes the deciding blow in the battle. Psalms and Proverbs are the supreme manual for spiritual warfare, for fighting both flesh-and-blood and spiritual enemies. Knowing that the devil is God’s devil brings us incalculable joy and confidence in battle with our adversary.

A Different Mode

The OT teaches a worldview and method of fighting spiritual evil that is essentially different from EMM.

There is a radical focus on the Lord—God is at absolute center stage.

Human beings are always responsible moral agents and share center stage with God.

Although the OT acknowledges the activity of Satan and his demons, it shows that God is sovereign and the demons are constrained.

God’s sovereignty has striking implications for the OT’s mode of spiritual warfare, mode of ministry, mode of living the godly life, and mode of fighting multifaceted evil. The mode of warfare God taught was having faith in the Word of God, fearing God, turning from evil involvements, taking refuge in the Lord, and obeying his voice. EMM is never the mode of warfare.

Sin and Suffering

Proponents of EMM make two major arguments:

Because Jesus and the apostles cast out demons, we should do likewise.

Because EMM is not forbidden by Jesus or the rest of the NT, there is no reason not to use it.

Powlison argues that the Bible does not teach us to wage spiritual warfare using EMM. Rather Scripture teaches us a different way to live the Christian life and fight our ancient foe.

The Dominion of Darkness Entails Sin and Suffering

One key to understanding spiritual warfare in the ministry of Jesus Christ is to notice that he mounted a twin-pronged offensive against the powers of evil—against moral evil and situational evil. Jesus employed two modes of warfare to address two different facets of the evil works of the devil.

Moral evil = the evil people believe and do.

Situational evil = the evil we experience (suffering, hardship, unpleasant and harmful events, death)

The two meanings of evil are closely linked; Satan employs both for his evil purposes.

God consistently portrays inhabiting evil spirits as situational—not moral—evil that hurt and abuse people. Sins, such as unbelief, fear, anger, lust, and other addictions, point to Satan’s moral lordship, but never to demonization calling EMM. Jesus usually approaches the sick from the angle of sufferers needing relief, not sinners needing repentance. Contrary to EMM teaching, unclean spirits are never implicated as holding people in bondage to unbelief and sin.

Whenever and wherever Jesus addressed Satan’s attempt to establish or maintain evil moral lordship, he used the non-EMM, classic mode of spiritual warfare. Jesus always used the classic mode to deal with moral evil; he used both the classic and ekballistic modes to deal with situational evil.

Jesus’ Mode of Ministry and Ours

“Eleven examples of Jesus’ works that we are called to do in a fashion different from our master. Notice three things after each example.

First, Jesus addresses genuine human needs that continue today.

Second, Jesus performs a particular action in an unusually striking and authoritative way, a command-control mode: ‘I say it, it happens.’

Third, we are told—by precept or example—to accomplish the same work but in a different way, the classic faith-obedience mode.” (p. 77)

Pay taxes

Catch fish

Walk on water

Feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty

Speak with God’s authority

Call people to ministry

Forgive sins

Confront and curse sin

Raise the dead

Control the weather

Heal the sick

Dealing with Demonic Affliction

Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Acts portray Jesus and the apostles as using the command-control mode to address sickness, the weather, paying taxes, speaking with personal authority, and so forth. The rest of the New Testament, following the main approach in the Old Testament, exemplifies and commands a different mode. Is there a similar switch for dealing with demons associated with ailments and afflictions?

We certainly will not be surprised to find a mode shift. Scripture is ‘silent’ on the issue in the same way it is silent on paying taxes, performing resurrections, or stilling storms by words of command. The silence thunders. The mode of addressing demonically induced sufferings reverts to the classic mode: Live the Christian life of receptive faith and active obedience in the midst of life’s hardships….

The modern demon-deliverance ministries are predicated on two fundamental errors. First, they misread the biblical record and fail to distinguish between moral and situational evil. They cast out ‘demons’ of moral evil, something neither taught nor illustrated anywhere in Scripture. Second, they fail to reckon with the general mode shift away from the command-control mode and toward the classic mode.

Steps to a Far More Powerful Way

Fight and win spiritual warfare through discovering the Creator God who rules heaven and earth.

Fight and win spiritual warfare through learning to find refuge in the Lord Jesus Christ.

Fight and win spiritual warfare through learning to dig into the Scripture in search of true wisdom.

Fight and win spiritual warfare through stopping fighting alone.

Fight and win spiritual warfare through growing to understand the thoughts and intentions of his heart.

Fight and win spiritual warfare through speaking words that do genuine good to others.

Fight and win spiritual warfare through honest work

Fight and win spiritual warfare through learning to aim your heart at what true prayer intends.

Fight and win spiritual warfare through not giving in to cultivated lusts

September 5, 2012

Counterfeit Gods

You can also download this spoken word on iTunes (all proceeds go to benefit a new college ministry).

Some further resources on this important biblical theme:

David Powlison, “Idols of the Heart and Vanity Fair,” Journal of Biblical Counseling (also available in PDF).

David Clarkson, “Soul Idolatry Excludes Men out of Heaven” (1622-1686)

Tim Keller, Counterfeit Gods (watch his TGC talk here)

G.K. Beale, We Become What We Worship: A Biblical Theology of Idolatry

Paul Tripp, Sex and Money: Pleasures That Leave You Empty and Grace That Satisfies (forthcoming in April 2013 from Crossway)

The Republican and Democratic Party Platforms on Abortion (1976-2012)

Kevin DeYoung reprints the respective parties’ platforms—Republicans and Democrats—for the past 36 years (after Roe v. Wade).

Kevin DeYoung reprints the respective parties’ platforms—Republicans and Democrats—for the past 36 years (after Roe v. Wade).

Here is his summary points for the Republicans:

Initially, the party was much more hesitant to take a firm stance on abortion.

The pro-life statements have generally gotten more expansive over the years.

The position has not really changed since 1980. The last three platform statements (2004, 2008, 2012) have been very similar.

I could not find language on abortion in 1984. It’s probably in there and I just didn’t see it. Curiously, though, 1984 was the only year for which I couldn’t find a Democratic statement on abortion. If the statements were in there and I missed them, they must not have been a big deal.

And here are some observations on the Democrats:

The Democratic statements tend to be shorter. They emphasize the right to choose and then move on fairly quickly in most instances.

In recent years, the platform has emphasized that abortion should be legal but also rare. The statements often celebrate the right to choose an abortion while at the same time celebrating the decline of the abortion rate.

Like the Republicans, the Democrats were hesitant to be too dogmatic about abortion in the immediate aftermath of Roe v. Wade (1973).

The Democrats included a strong statement of inclusion (respect for differing opinions on abortion) in their 2000 platform. I did not see the same language in 2004, 2008, or 2012. In fact, judging by the past few weeks and this year’s convention, the Democrats are making a gamble that pushing leftward on abortion is a winning strategy.

Kevin’s final point was confirmed by the start of the Democratic National Convention: the Democrats have chosen a new tact this year in explicitly highlighting and celebrating their support of unrestricted legal abortion. It’s an interesting strategy, given that those self-identifying as “pro-choice” are at a recorded-low. The theme, however, is consistent with the fact that President Obama—whether you agree or disagree with his philosophy in other areas, has to be acknowledged as the most extreme presidential advocate of abortion-rights in American political history.

On the Republican side, inarticulate advocates of life like Todd Akin have certainly not helped the cause or the case for life. The best article on his mind-numbing gaffe and its aftermath can be found here.

It’s important to point out, however, that the Republic Party platform on this is important and not inconsequential. Pro-life presidents do matter. And despite the fact that Roe v. Wade is still the law of the land, 2011-2012 was a record year in terms of pro-life legislation at the state level.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers