Justin Taylor's Blog, page 191

September 16, 2012

Why the Reformation Matters

Steve Nichols is not only the winner of the Nicest Guy in the World Award® but also tops the charts in Twice as Old as He Looks® category. He’s not only a good scholar and author, but also an exceptional teacher. You can see this in the free lecture below, “Why the Reformation Matters,” part of his Reformation Profiles series from Ligonier. (Free study guide also available.)

For related books from Nichols, see The Reformation: How a Monk and a Mallet Changed the World and Martin Luther: A Guided Tour of His Life and Thought (Packer says, “For half a century, Bainton’s Here I Stand has been the best introduction to Luther. Stephen Nichols’s engaging volume is in many ways better than Bainton’s for this purpose. It deserves to be widely read.”)

September 15, 2012

C. S. Lewis on the Four Loves and Friendship

Lewis scholar Louis Markos—the author of Lewis Agonistes: How C.S. Lewis Can Train Us to Wrestle with the Modern and Postmodern World, Restoring Beauty: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the Writings of C.S. Lewis, and On the Shoulders of Hobbits: The Road to Virtue with Tolkien and Lewis—lectures below at Houston Baptist University on Lewis’s The Four Loves and on friendship in particular.

The lecture begins around the 5:00 mark.

September 14, 2012

An Introduction to Ancient Church History

Ligonier Ministries has filmed an ambitious new 60-hour survey of church history featuring Dr. Robert Godfrey, president of Westminster Theological Seminary, California. The first part, 12 talks on on AD 100-600, is now available in both audio and video. You can also download a free study guide.

You can watch the introductory lecture below:

September 13, 2012

The Trailer for Lincoln

The trailer for Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln is now online:

September 12, 2012

A Book Packer Thinks You Should Read Three Times

J. I. Packer on Don Whitney’s Spiritual Disciples for the Christian Life:

J. I. Packer on Don Whitney’s Spiritual Disciples for the Christian Life:

* * *

I can go on record as urging all Christians to read what Don Whitney has written; indeed, to read it three times over, with a month’s interval (certainly not less, and ideally, I think, not more) between each reading. This will not only make the book sink in, but will also give you a realistic picture of your seriousness, or lack of it, as Jesus’ disciple.

Your first reading will show you several particular things that you should start doing.

In your second and third readings (for each of which you should choose a date on the day you complete the previous reading) you shall find yourself reviewing what you have done and how you have fared in doing it. That will be very good for you, even if the discovery of it comes as a bit of a shock at first.

On Thick vs. Thin Authorial Intent in the Bible

From an interview with Greg Beale:

If you’re going to do grammatical-historical exegesis of the Old Testament one of the first things you must do—whether you’re a higher critic, a non-conservative, or a conservative—is recognize that the Old Testament writers understood that they were under divine inspiration. If you’re going to do this sort of exegesis you’ve got to include that. Too many people fail to do this. How would this realization effect our understanding of an Old Testament authors’ intention? Would an Old Testament author say “What I’m saying here should just be narrowly understand in this narrow historical context”? Or, would the Old Testament author allow that his intention is thicker and larger than even he understood it because he believed he was writing under divine inspiration?

Perhaps an illustration would help. If I were to have a student over to my house and I said “Ah, there’s nothing I enjoy more in the summer than sitting on the patio, sipping lemonade, and listening to Bach.” Now, if that student comes to you and says “Hey, I was over at Beale’s house and he says that he really enjoys sipping lemonade and listening to Bach.” And then you ask, “Well, does he like other composers like Vivaldi? Does he like Pachabel?” The answer to that would be “Yes,” because I’m really just referring to Bach as a part for a whole. There is more in my intention, which is very thick. Now, if you asked, “Does he like hard rock like Carl Trueman does?” the answer would be “No,” because that is outside of what I would call my “peripheral intention.” Even though I did not have Vivaldi and Pachabel in my narrow intention when I spoke, it would be correct to think that they are a part of my wider attention.

So we’re not so much talking about a state of mind but what clues are in the text. I don’t think I’m guilty of making the authorial fallacy—we’re concerned about what evidence the text gives as to what was intended by the author. What the illustration gets at is that intentions can be much “thicker” and need to be unpacked, even when someone is speaking or writing who is not divinely inspired – how much more would this be the case for an inspired writer. Thus, it is legitimate in a grammatical-historical way to pursue this. I would say if you’re going to do grammatical-historical exegesis you must recognize that the Old Testament authors considered themselves inspired and you must take that into consideration. Most people don’t do this in their grammatical-historical exegesis, so in some ways I’m redefining the concept because I think it is too narrowly defined by too many people. Vern Poythress has written quite a bit about this particular topic, and I would direct readers to some of his works.

You can read the whole, wide-ranging interview here.

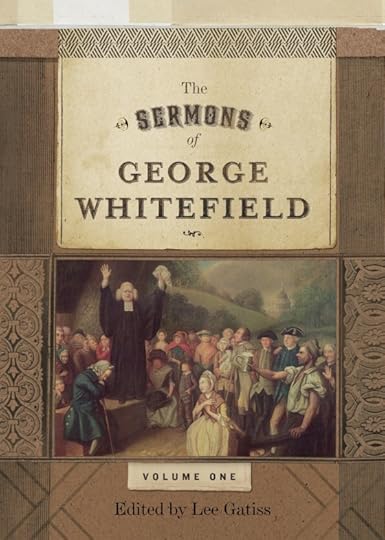

Would You Like to Hear George Whitefield Preach?

The new two-volume set of sermons by George Whitefield, expertly edited by Lee Gatiss and published by Crossway, is now available for almost 50% off. Or the Kindle edition is 85% off ($9.99). [I don't know how long the Kindle price will be that low.]

You can read some samples here.

Here is some encouragement to read Whitefield for yourself:

“George Whitefield was undoubtedly one of the greatest preachers of the modern Christian era, yet today he remains strangely neglected, even among evangelical Christians. Lee Gatiss’s excellent edition of Whitefield’s sermons will alleviate some of this undeserved obscurity. Pastors, professors, and laypeople would all do well to reflect on these sermons, which more than any other earthly force helped stir the massive revivals of the Great Awakening.”

—Thomas Kidd, Associate Professor of History, Baylor University; author, The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America [Note: Kidd is writing a major biography of Whitefield for Yale University Press, due to be published, I believe, on Whitefield's 300th birthday in 2014.]

“Lee Gatiss has done us a service—dusting off, tidying up, and re-presenting Whitefield’s electric preaching to a new age. Gatiss’s introduction to the sermons is worth the price of the volumes alone. My prayer is that these sermons will raise up, and stir up, a generation to preach with gospel fire. Amen and Amen.”

—Josh Moody, Senior Pastor, College Church, Wheaton, Illinois; author, The God-Centered Life: Insights from Jonathan Edwards

“George Whitefield has impacted my life and ministry more than I could ever measure. I could not be more excited about these sermons being back in print. One can only pray that the same Lord who used these sermons to shake the world so long ago will give us another Great Awakening through them. Whitefield’s own prayer for these sermons would surely accord with what he said when he gave the leadership of the Methodist movement to Wesley, ‘Let the name of Whitefield perish, if only the name of Christ be glorified.’”

—Jason C. Meyer, Associate Pastor for Preaching and Vision, Bethlehem Baptist Church, Minneapolis, Minnesota

“I have read some comments on the printed sermons of Whitefield that say these sermons don’t translate well to the written medium. Well, I am sure it would have been amazing to hear him preach; but, given that, I find the written sermons to have an intrinsic fervor, power, clarity, and theological pungency that still leaps off the page into the conscience and affections in a gripping and edifying way. This publication is welcome; it will do us good and demonstrates once again that God’s truth transcends all generations and cultures and that God only rarely gives gifts to the church as transparently good as George Whitefield. Thanks to Lee Gatiss and thanks to Crossway.”

—Tom J. Nettles, Professor of Historical Theology, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary

September 11, 2012

Avoiding Logical Fallacies in Theology

Michael Horton provides some examples of informal logical fallacies, which should be avoided when writing a theological paper in his classes (and, of course, in all of life!). I’ve reprinted below the ones that he lists (along with some images, which have some relevance to the fallacy in one way or another).

First and foremost we need to avoid the ubiquitous ad hominem (“to/concerning the person”) variety—otherwise known as “personal attacks.”

Poor papers often focus on the person: both the critic and the one being criticized. This is easier, of course, because one only has to express one’s own opinions and reflections. A good paper will tell us more about the issues in the debate than about the debaters. (This of course does not rule out relevant biographical information on figures we’re engaging that is deemed essential to the argument.)

Closely related are red-herring arguments: poisoning the well, where you discredit a position at the outset (a pre-emptive strike), or creating a straw man (caricature) that can be easily demolished.

“Barth was a liberal,” “Roman Catholics do not believe that salvation is by grace,” “Luther said terrible things about Jews and Calvin approved the burning of Servetus—so how could you possibly take seriously anything they say?”

It’s an easy way of dismissing views that may be true even though those who taught them may have said or done other things that are reprehensible.

Closely related is the genetic fallacy, which requires merely that one trace an argument or position back to its source in order to discount it.

Simply to trace a view to its origin—as Roman Catholic, Arminian, Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptist/Baptist, etc.—is not to offer an argument for or against it. For example, we all believe in the Trinity; it’s not wrong because it’s also held by Roman Catholics. “Barth studied under Harnack and Herrmann, so we should already consider his doctrine of revelation suspect.” This assertion does not take into account the fact that Barth was reacting sharply against his liberal mentors and displays no effort to actually read, understand, and engage the primary or secondary sources.

Closely related to these fallacies is the all too familiar slippery slope argument. “Barth’s doctrine of revelation leads to atheism” or “Arminianism leads to Pelagianism” or “Calvinism leads to fatalism” would be examples. Even if one’s conclusion is correct, the argument has to be made, not merely asserted. The fact is, we often miss crucial moves that people make that are perfectly consistent with their thinking and do not lead to the extreme conclusions we attribute to them—not to mention the inconsistencies that all of us indulge. Honesty requires that you engage the positions that people actually hold, not conclusions you think they should hold if they are consistent.

If you’re going to make a logical argument that certain premises lead to a certain conclusion, then you need to make the case and must also be careful to clarify whether the interlocutor either did make that move or did not but (logically) should have.

Another closely related fallacy here is sweeping generalization. Until recently, it was common for historians to try to explain an entire system by identifying a “central dogma.” For example, Lutherans deduce everything from the central dogma of justification; Calvinists, from predestination and the sovereignty of God. Serious scholars who have actually studied these sources point out that these sweeping generalizations don’t have any foundation. However, sweeping generalizations are so common precisely because they make our job easier. We can embrace or dismiss positions easily without actually having to examine them closely. Usually, this means that a paper will be more “heat” than “light”: substituting emotional assertion for well-researched and logical argumentation.

“Karl Barth’s doctrine of revelation is anti-scriptural and anti-Christian” is another sweeping generalization. If I were to ask you in person why you think Barth’s view of revelation is “anti-scriptural anti-Christian,” you might answer, “Well, I think that he draws too sharp a contrast between the Word of God and Scripture—and that this undermines a credible doctrine of revelation.” “Good,” I reply, “now why do you think he makes that move?” “I think it’s because he identifies the ‘Word of God’ with God’s essence and therefore regards any direct identification with a creaturely medium (like the Bible) as a form of idolatry. It’s part of his ‘veiling-unveiling’ dialectic.” OK, now we’re closer to a real thesis—something like, “Because Barth interprets revelation as nothing less than God’s essence (actualistically conceived), he draws a sharp contrast between Scripture and revelation.” A good argument for something like that will allow the reader to draw conclusions instead of strong-arming the reader with the force of your own personality.

Also avoid the fallacy of begging the question. For example, question-begging is evident in the thesis statement: “Baptists exclude from the covenant those whom Christ has welcomed.” After all, you’re assuming your conclusion without defending it. Baptists don’t believe that children of believers are included in the covenant of grace. That’s the very reason why they do not baptize them. You need an argument.

You can read the whole thing here, where he explains the importance of this for Christian piety and virtue.

For more on logical fallacies, you could consult a book like Peter Kreeft’s Socratic Logic or Norman Geisler and Ronald Brooks’s Come, Let Us Reason: An Introduction to Logical Thinking. Or see this nice free PDF summary chart, “Thou Shalt Not Commit Logical Fallacies.”

For more on essay writing in seminary, see this good overview by R. Scott Clark as well as this insight but more general piece by John Frame. Those in the UK could order the little book by Michael Jensen, How to Write a Theological Essay.

If You’re United to Christ You’re Part of the New Creation Order

Richard Gaffin explains 2 Corinthians 5:17:

Three Essential Things for a “Good Work”

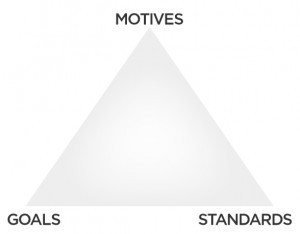

The Westminster Confession of Faith (16.7) is quite helpful in summarizing why works that are externally good are not pleasing in the sight of the Lord:

Works done by unregenerate men,

although for the matter of them they may be things which God commands,

and of good use both to themselves and others;

yet, because

[1] they proceed not from a heart purified by faith;

[2] nor are done in a right manner, according to the Word;

[3] nor to a right end, the glory of God;

they are therefore sinful and can not please God, or make a man meet to receive grace from God.

And yet their neglect of them is more sinful, and displeasing unto God.

In other words, having the right motive, the right standard, and the right goal are the three necessary and sufficient conditions for good works according to the Bible.

I appreciate in particular that this summary takes seriously the biblical themes that “without faith it is impossible to please [God]” (Heb. 11:6) and that “whatever does not proceed from faith is sin” (Rom. 14:23) and that faith working through love—for God and for our neighbor—is essential (1 Corinthians 13; Luke 10:27; Gal. 5:6, etc.) and that all things are to be done for God’s glory in accordance with his revealed will (1 Cor. 10:31).

This triad is also helpful for thinking about what it means to do everyday activities in a Christian way. For example, John Frame writes:

In everything we do, we seek to obey God’s commands. There are, of course, human activities for which there are no explicit biblical prescriptions. Scripture doesn’t tell us how to change a tire, for instance. But there are biblical commands that are relevant to tire changing, as to everything else.

In all activities, we are to glorify God (1 Cor. 10:31).

In everything we are to be motivated by faith (Rom. 14:23) and love (1 Cor. 13:1-3).

In everything, we are to act in the name of the Lord Jesus (Col. 3:17), with all our heart (3:23). When I change a tire, I should do it to the glory of God.

The details I need to work out myself, but always in the framework of God’s broad commands concerning my motives and goals.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers