Justin Taylor's Blog, page 201

July 12, 2012

The Danger of Seductive Applause

D. A. Carson:

John Woodbridge and I had come to the conclusion that we ought to edit a couple of tough-minded books on the doctrine of Scripture, books that ultimately became Scripture and Truth and Hermeneutics, Authority, and Canon. In my recruitment of writers for this project I approached a friend I had known since Cambridge days who was then teaching at another university, and who, I knew, shared our views on how Christians are to think about Scripture and what the long-sustained history of the doctrine is. He replied that although he wished our project well, he did not want to write on a subject like that, since he thought it would queer any chance he might have of getting a post at Oxford or Cambridge, where he could eventually do a lot more good. My response was that if he took that approach to confessional matters, it would not be long before he distanced himself not only from defending the doctrine, but from the doctrine itself. And that, I regret to tell you, is exactly what happened over the ensuing years. Beware the seduction of academic applause.

The second direction from which seductive applause may come is the conservative constituency of your friends, a narrower peer group but one that, for some people, is equally ensnaring. Scholarship is then for sale: you constantly work on things to bolster the self-identity of your group, to show they are right, to answer all who disagree with them. Some scholars who are very indignant with colleagues who, in their estimation, are far too attracted by the applause of unbelieving academic peers, remain blissfully unaware of how much they have become addicted to the applause of conservative bastions that egg them on.

—D.A. Carson, “The Scholar as Pastor,” in The Pastor as Scholar and the Scholar as Pastor, by Piper and Carson; ed. Mathis and Strachan (Crossway, 2011). (This talk is also available as a 17-page PDF, MP3 file, and video–all online for free.)

What a 17th Century Puritan Wants You to Do with Your “Hard Thoughts” about God

John Owen:

Flesh and blood is apt to have very hard thoughts of him — to think he is always angry, yea, implacable; that it is not for poor creatures to draw nigh to him. . .

Many saints have no greater burden in their lives than that their hearts do not come clearly and fully up, constantly to delight and rejoice in God — that there is still an indisposedness [unwillingness] of spirit unto close walking with him.

What is at the bottom of this distemper?

Is it not their unskillfulness in or neglect of this duty, even of holding communion with the Father in love?

So much as we see of the love of God, so much shall we delight in him, and no more.

Every other discovery of God, without this, will but make the soul fly from him; but if the heart be once much taken up with this the eminency of the Father’s love, it cannot choose but be overpowered, conquered, and endeared unto him.

This, if anything, will work upon us to make our abode with him.

If the love of a father will not make a child delight in him, what will?

Put, then, this to the venture: exercise your thoughts upon this very thing, the eternal, free, and fruitful love of the Father, and see if your hearts be not wrought upon to delight in him. I dare boldly say: believers will find it as thriving a course as ever they pitched on in their lives. Sit down a little at the fountain, and you will quickly have a further discovery of the sweetness of the streams. You who have run from him, will not be able, after a while, to keep at a distance for a moment.

John Owen, Communion with the Triune God, pp. 126, 128.

July 11, 2012

Should You Pray for God to Save Your Loved Ones? (Or, Why You Both Pray and Sleep Like a Calvinist)

Calvinists hear Arminian friends ask this question all the time. It’s usually intended as a rhetorical question. In other words, it’s really a statement: If you believe that your unbelieving friend is dead in sin until God unilaterally regenerates him or her, and that God has unconditionally chosen whom he will save, then what’s the point? Que sera, sera: Whatever will be, will be.

Of course, this is a terrific objection to hyper-Calvinism, but misses its Reformed target. Our confessions teach that God works through means. Though the Father has chosen unconditionally some from our condemned race for everlasting life in his Son, the elect were not redeemed until he sent his Son “in the fullness of time,” and they are not justified until the Spirit gives them faith in Christ through the gospel. To invoke Paul’s argument (on the heels of teaching unconditional election), “How then will they call on him in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in him of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone preaching? And how are they to preach unless they are sent?…So faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ” (Rom 10:14-15, 17).

For years now, I’ve reversed this rhetorical question, asking, Why would anyone pray for the conversation of their loved one if God were not sovereign in dispensing his grace? Arminians shouldn’t pray for God to save their loved ones, because God could reply, “Look, I’ve done my part; now the ball is in your court.” Yet, I note, Arminians are typically no less zealous in praying for the salvation of the lost than Calvinists. We’re at one on our knees.

Not so quickly, says Roger Olson, a distinguished Baptist professor and author of Arminian Theology. By now, readers of this blog may know that my friend Roger and I have been engaged in conversations about these things. He wrote, Against Calvinism, and I wrote For Calvinism, and we have taken up these issues in person as part of our White Horse Inn “Conversations” series. We’re both trying to understand each other’s views charitably, if nevertheless critically. In that spirit, the following…

In a recent post, Roger stirred up a hornet’s nest by suggesting that “Arminians should not pray to God to save their friends and loved ones.” It may be that one is using “save” differently. However, “Normal language interpretation would seem to me to indicate that asking God to save someone, without any qualifications, is tantamount (whatever is intended) to asking God to do the impossible (from an Arminian perspective).”

You can read the whole thing here.

The Philosophy In and Behind “The Lord of the Rings”

Peter Kreeft’s The Philosophy of Tolkien: The Worldview Behind The Lord of the Rings (Ignatius, 2005) is an enjoyable and edifying book. He is an unabashed fan of The Lord of the Rings, which he considers one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century. In this book he works through 50 of the great questions using four tools:

Peter Kreeft’s The Philosophy of Tolkien: The Worldview Behind The Lord of the Rings (Ignatius, 2005) is an enjoyable and edifying book. He is an unabashed fan of The Lord of the Rings, which he considers one of the greatest novels of the twentieth century. In this book he works through 50 of the great questions using four tools:

an explanation of the meaning and importance of the question;

a key quotation from The Lord of the Rings showing how Tolkien answered the question (many more passages are given in the Concordance to The Lord of the Rings in the Appendix);

a quotation from Tolkien’s other writings (usually a letter) that explains or comments on the theme in The Lord of the Rings;

a quotation from C. S. Lewis, Tolkien’s closest friend, showing the same philosophy directly stated.

For me, the Lewis quotes alone were worth the price of the book.

Here’s the outline of worldview issues addressed (at least in part) by The Lord of the Rings.

1. Metaphysics

1.1 How big is reality?

1.2 Is the supernatural real?

1.3 Are Platonic Ideas real?

2. Philosophical Theology

2.1 Does God exist?

2.2 Is life subject to divine providence?

2.3 Are we both fated and free?

2.4 Can we relate to God by “religion”?

3. Angelology

3.1 Are angels real?

3.2 Do we have guardian angels?

3.3 Could there be creatures between men and angels, such as Elves?

4. Cosmology

4.1 Is nature really beautiful?

4.2 Do things have personalities?

4.3 Is there real magic?

5. Anthropology

5.1 Is death good or bad?

5.2 Is romance more thrilling than sex?

5.3 Why do humans have identity crises?

5.4 What do we most deeply desire?

6. Epistemology

6.1 Is knowledge always good?

6.2 Is intuition a form of knowledge?

6.3 Is faith (trust) wisdom or ignorance?

6.4 What is truth?

7. Philosophy of History

7.1 Is history a story?

7.2 Is the past (tradition) a prison or a lighthouse?

7.3 Is history predictable?

7.4 Is there devolution as well as evolution?

7.5 Is human life a tragedy or a comedy?

8. Aesthetics

8.1 Why do we no longer love glory or splendor?

8.2 Is beauty always good?

9. Philosophy of Language

9.1 How can words be alive?

9.2 The metaphysics of words: Can words have real power?

9.3 Are there right and wrong words?

9.4 Is there an original, universal, natural language?

9.5 Why is music so powerful?

10. Political Philosophy

10.1 Is small beautiful?

10.2 Can war be noble?

11. Ethics: The War of Good and Evil

11.1 Is evil real?

11.2 How powerful is evil?

11.3 How weak is evil?

11.4 How does evil work?

12. Ethics: The “Hard” Virtues

12.1 Do principles or consequences make an act good?

12.2 Why must we be heroes?

12.3 Can one go on without hope?

12.4 Is authority oppressive and obedience demeaning?

12.5 Are promises sacred?

13. Ethics: The “Soft” Virtues

13.1 What is the power of friendship?

13.2 Is humility humiliating?

13.3 What should you give away?

13.4 Does mercy trump justice?

13.5 Is charity a waste?

14. Conclusion

Can any one man incarnate every truth and virtue?

Below is the outline for his philosophical concordance of The Lord of the Rings. I don’t think the publisher would like it if I included the page references in the concordance, but the outline may whet your appetite. (If you get the book, the passage locations are all keyed to the one-volume edition of LOTR.)

1. Metaphysics

1.1. Metaphysical realism: that reality is more than appearance, more than our consciousness, and more than our expectations

1.2. Supernaturalism: that reality is more than the natural (matter, time, and space)

1.3. Platonism: archetypes

2. Philosophical Theology

2.1. God

2.2. Divine providence (especially providential timings and “coincidences”)

2.3. Fate (or predestination, or destiny) and free will

2.4. Religion

3. Angelology

3.1. The reality of angels

3.2. The task of angels: guardians

3.3. Elves as halfway between the human and the angelic

4. Cosmology

4.1. The beauty of the cosmos

4.2. The personality of things in the world

4.3. Magic in the world and man

5. Anthropology

5.1. Death

5.2. Romance

5.3. The perilous status of selfhood; the flexibility of the self

5.4. Sehnsucht, longing (especially for the sea)

6. Epistemology

6.1. Knowledge is not always good

6.2. Knowledge by intuition

6.3. Knowledge by faith (trust)

6.4. Truth

7. Philosophy of History

7.1. Teleology, story, purpose, “road”

7.2. Tradition, collective memory, legends

7.3. The freedom and unpredictability of history

7.4. Devolution, pessimism

7.5. Eucatastrophe, optimism

8. Aesthetics

8.1. Formality, “glory,” height

8.2. Beauty and goodness

9. Philosophy of Language

9.1. Names and language in general

9.2. Proper names

9.3. The magical power of words

9.4. Music

10. Political Philosophy

10.1. Populism, “small is beautiful”

10.2. Peace and war

11. Ethics

11.1. Spiritual warfare

11.2. The power of evil and the evil of power

11.3. The weakness of evil

11.4. The strategy of evil; the mechanism of temptation (especially the Ring)

12. Ethics: The Hard Virtues

12.1. Duty versus utility

12.2. Courage

12.3. Hope versus despair

12.4. Obedience to authority

12.5. Honesty, truthfulness, keeping promises

13. Ethics: The Soft Virtues

13.1. Friendship, fellowship

13.2. Humility, “hobbitry”

13.3. Gifts

13.4. Pity

13.5. Charity; the gift of self

14. The Fulfillment of All the Points: Christ

Humility in Interpretation (Or, On Not Coloring Outside the Theological Lines)

John Calvin:

Here, indeed, if anywhere in the secret mysteries of Scripture, we ought to play the philosopher soberly and with great moderation; let us use great caution that neither our thoughts nor our speech go beyond the limits to which the Word of God itself extends.

For how can the human mind measure off the measureless essence of God according to its own little measure . . . ? Let us then willingly leave to God the knowledge of himself. . . . But we shall be “leaving it to him” if we conceive him to be as he reveals himself to us, without inquiring about him elsewhere than from his Word. . . .

And let us not take it into our heads either to seek out God anywhere else than in his Sacred Word, or to think anything about him that is not prompted by his Word, or to speak anything that is not taken from his Word.

Calvin, Institutes (McNeill/Battles), I.XIII.21.

See also I.XIV.3, 4:

. . . Nevertheless, we will take care to keep to the measure which the rule of godliness prescribes, that our readers may not, by speculating more deeply than is expedient, wander away from simplicity of faith. And in fact, while the Spirit ever teaches us to our profit, he either remains absolutely silent upon those things of little value for edification, or only lightly and cursorily touches them. It is also our duty willingly to renounce those things which are unprofitable. . . .

Let us remember here, as in all religious doctrine, that we ought to hold to one rule of modesty and sobriety: not to speak, or guess, or even to seek to know, concerning obscure matters anything except what has been imparted to us by God’s Word. Furthermore, in the reading of Scripture we ought ceaselessly to endeavor to seek out and meditate upon those things which make for edification. Let us not indulge in curiosity or in the investigation of unprofitable things. And because the Lord willed to instruct us, not in fruitless questions, but in sound godliness, in the fear of his name, in true trust, and in the duties of holiness, let us be satisfied with this knowledge. For this reason, if we would be duly wise, we must leave those empty speculations which idle men have taught apart from God’s Word concerning the nature, orders, and number of angels. I know that many persons more greedily seize upon and take more delight in them than in such things as have been put to daily use. But, if we are not ashamed of being Christ’s disciples, let us not be ashamed to follow that method which he has prescribed. Thus it will come to pass that, content with his teaching, we shall not only abandon but also abhor those utterly empty speculations from which he calls us back.

July 10, 2012

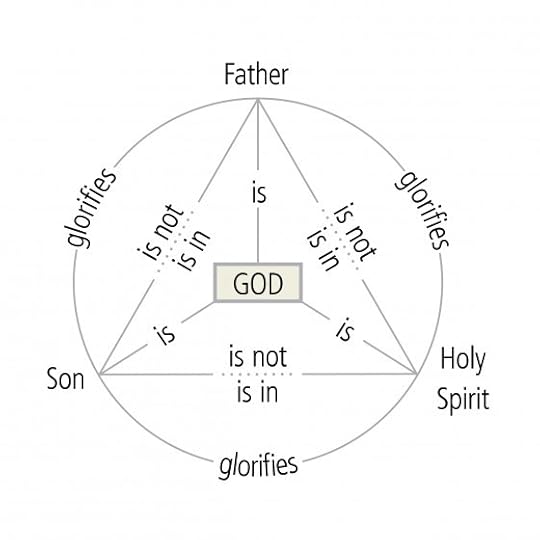

Using a Diagram to Illustrate Trinitarian Relationships

The above is one attempt, not to illustrate the Trinity per se, but rather to capture in a diagram some of the truths related to the persons of the Godhead.

The above is one attempt, not to illustrate the Trinity per se, but rather to capture in a diagram some of the truths related to the persons of the Godhead.

The internal lines identify the nature, substance, or essence of each person:

The Father is God.

The Son is God.

The Holy Spirit is God.

As Basil of Caesarea writes in the 370s (Letter 236.6):

The distinction between ousia and hupostasis is the same as that between the general and the particular; as, for instance, between the animal and the particular man.

Wherefore, in the case of the Godhead, we confess one essence or substance so as not to give a variant definition of existence, but we confess a particular hypostasis, in order that our conception of Father, Son and Holy Spirit may be without confusion and clear. If we have no distinct perception of the separate characteristics, namely, fatherhood, sonship, and sanctification, but form our conception of God from the general idea of existence, we cannot possibly give a sound account of our faith.

We must, therefore, confess the faith by adding the particular to the common. The Godhead is common; the fatherhood particular. We must therefore combine the two and say, I believe in God the Father.

The like course must be pursued in the confession of the Son; we must combine the particular with the common and say I believe in God the Son, so in the case of the Holy Ghost we must make our utterance conform to the appellation and say in God the Holy Ghost.

The lines of the triangle represent two sets of propositions. First, they remind us that while each of the persons in the Godhead is God (fully divine), the persons are at the same time distinct. In other words:

The Father is not the Son.

The Son is not the Father.

The Father is not the Holy Spirit.

The Holy Spirit is not the Father.

The Son is not the Holy Spirit.

The Holy Spirit is not the Son.

After all, the Father is never “sent” in Scripture. Nor is he incarnated or poured out at Pentecost. The Spirit does not die on the cross for our sins. The Father begets the Son, not vice-versa. The Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son.

Another aspect indicated by the lines on the triangle is that of mutual indwelling (or perichoresis). The three persons indwell each other in the one being of God. So:

The Father is in the Son.

The Son is in the Father.

The Father is in the Holy Spirit.

The Holy Spirit is in the Father.

The Son is in the Holy Spirit.

The Holy Spirit is in the Son.

Finally, each of the three persons in the one being of God glorify one another. As Gregory of Nyssa writes, there is a “revolving circle” of glory:

The Son is glorified by the Spirit; the Father is glorified by the Son; again the Son has His glory from the Father; and the Only-begotten thus becomes the glory of the Spirit. . . . In like manner, again, Faith completes the circle, and glorifies the Son by means of the Spirit, and the Father by means of the Son. (Gregory of Nyssa, On the Holy Spirit, in NPNF, Second Series, 5:324).

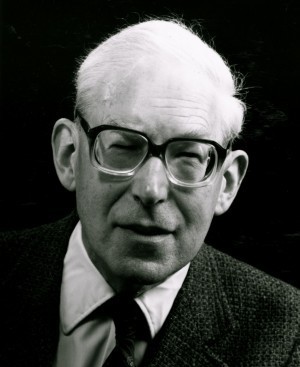

How “Let Go and Let God” Almost Ruined J. I. Packer’s Spiritual Life

J. I. Packer, in his introduction to John Owen’s The Mortification of Sin, writes that

I was converted – that is, I came to the Lord Jesus Christ in a decisive commitment, needing and seeking God’s pardon and acceptance, conscious of Christ’s redeeming love for me and his personal call to me – in my first university term, a little more than half a century ago. The group nurturing me was heavily pietistic in style, and left me in no doubt that the most important thing for me as a Christian was the quality of my walk with God: in which, of course, they were entirely right. They were also, however, somewhat elitist in spirit, holding that only Bible-believing evangelicals could say anything worth hearing about the Christian life, and the leaders encouraged the rest of us to assume that anyone thought sound enough to address the group on this theme was sure to be good. I listened with great expectation and excitement to the preachers and teachers whom the group brought in week by week, not doubting that they were the top devotional instructors in Britain, perhaps in the world. And I came a cropper.

Whether what I thought I heard was what was really being said may be left an open question, but it seemed to me that what I was being told was this. There are two sorts of Christians, first-class and second-class, ‘spiritual’ and ‘carnal’ (a distinction drawn from the King James rendering of 1 Cor. 3:1-3). The former know sustained peace and joy, constant inner confidence, and regular victory over temptation and sin, in a way that the latter do not. Those who hope to be of use to God must become ‘spiritual’ in the stated sense. As a lonely, nervy, adolescent introvert whose new-found assurance had not changed his temperament overnight, I had to conclude that I was not ‘spiritual’ yet. But I wanted to be useful to God. So what was I to do?

‘Let go, and let God’

There is a secret, I was told, of rising from carnality to spirituality, a secret mirrored in the maxim: Let go, and let God. I vividly recall a radiant clergyman in an Oxford pulpit enforcing this. The secret had to do with being Spirit-filled. The Spirit-filled person, it was said, is taken out of the second half of Romans 7, understood (misunderstood, I would now maintain) as an analysis of constant moral defeat through self-reliance, into Romans 8, where he walks confidently in the Spirit and is not so defeated. The way to be Spirit-filled, so I gathered, was as follows.

First, one must deny self. Did not Jesus require self-denial from his disciples (Luke 9:23)? Yes, but clearly what he meant was the negating of carnal self — that is to say self-will, self-assertion, self-centredness and self-worship, the Adamic syndrome in human nature, the egocentric behaviour pattern, rooted in anti-God aspirations and attitudes, for which the common name is original sin. What I seemed to be hearing, however, was a call to deny personal self, so that I could be taken over by Jesus Christ in such a way that my present experience of thinking and willing would become something different, an experience of Christ himself living in me, animating me, and doing the thinking and willing for me. Put like that, it sounds more like the formula of demon-possession than the ministry of the indwelling Christ according to the New Testament. But in those days I knew nothing about demon-possession,and what I have just put into words seemed to be the plain meaning of ‘I live; yet not I, but Christliveth in me’ (Gal. 2:20, KJV) as expounded by the approved speakers. We used to sing this chorus:

O to be saved from myself, dear Lord,

O to be lost in thee;

O that it may be no more I

But Christ who lives in me!

Whatever its author may have meant, I sang it wholeheartedly in the sense spelled out above. The rest of the secret was bound up in the double-barrelled phrase consecration and faith. Consecration meant total self-surrender, laying one’s all on the altar, handing over every part of one’s life to the lordship of Jesus. Through consecration one would be emptied of self, and the empty vessel would then automatically be filled with the Spirit so that Christ’s power within one would be ready for use. With consecration was to go faith, which was explained as looking to the indwelling Christ moment by moment, not only to do one’s thinking and choosing in and for one, but also to do one’s fighting and resisting of temptation. Rather then meet temptation directly (which would be fighting in one’s own strength), one should hand it over to Christ to deal with, and look to him to banish it. Such was the consecration-and-faith technique as I understood it – heap powerful magic, as I took it to be, the precious secret of what was called victorious living.

But what happened? I scraped my inside, figuratively speaking, to ensure that my consecration was complete, and laboured to ‘let go and let God’ when temptation made its presence felt. At that time I did not know that Harry Ironside, sometime pastor of Moody Memorial Church, Chicago, once drove himself into a full-scale mental breakdown through trying to get into the higher life as I was trying to get into it; and I would not have dared to conclude, as I have concluded since, that this higher life as described is a will-o’-the-wisp, an unreality that no one has ever laid hold of at all, and that those who testify to their experience in these terms really, if unwittingly, distort what has happened to them. All I knew was that the expected experience was not coming. The technique was not working. Why not? Well, since the teaching declared that everything depends on consecration being total, the fault had to lie in me. So I must scrape my inside again to find whatever maggots of unconsecrated selfhood still lurked there. I became fairly frantic.

And then (thank God) the group was given an old clergyman’s library, and in it was an uncut set of Owen, and I cut the pages of volume VI more or less at random, and read Owen on mortification – and God used what the old Puritan had written three centuries before to sort me out.

So if we don’t “let go and let God,” how do we kill sin? For Packer, Owen showed him the biblical answers: “I owe more, I think, to John Owen than to any other theologian, ancient or modern, and I am sure I owe more to his little book on mortification than to anything else he wrote.” You can read the rest of this introduction for a brief overview, or go on to read Owen’s book for yourself.

One neglected aspect of mortification is prayer. In this clip from an interview with Desiring God, Packer explains:

July 9, 2012

The Parable of the Flug in the Air

Ted Turnau, in his new book Popologetics: Popular Culture in Christian Perspective (see a TGC review here), offers a parable on pop culture:

Ted Turnau, in his new book Popologetics: Popular Culture in Christian Perspective (see a TGC review here), offers a parable on pop culture:

Once upon a time (in a galaxy not so far away), there lived a community much like ours. One day, their scientists stumbled upon a discovery: there was something in the air they breathed. They called it “flug,” for lack of a better name. They didn’t know where flug came from. Perhaps it was generated by the natural activities of the community’s life together. Perhaps it was an alien substance that had invaded. No one knew for sure. But one thing they did know: Flug changed people. In some, the change was radical and disturbing. In others, the change was more subtle. But every person, every breathing person, underwent a change. Most people didn’t even notice, or didn’t care. They just kept on breathing and changing and living their lives.

Some people became alarmed and angry. They moved away to the high and lofty mountains, hoping they wouldn’t have to breathe the flug-infested air. But being so high up, the sheer altitude and isolation changed them, but in a different way than people who breathed in the flug. And, as it turned out, they couldn’t really avoid it, any more than you or I can avoid breathing.

Some people actually enjoyed the change and became flug-enthusiasts. They saw flug as a doorway into a deeper understanding of the mysteries of life, or something like that. They couldn’t get enough. They even found a way to distill it and spike their cigarettes so as to increase their intake of flug. They called them “flugarettes.” Some people thought this group was being naïve in their surrender to flug, but you couldn’t really convince them otherwise. They just really, really enjoyed their flug.

And finally, there was a group of people who couldn’t decide what to think of flug. So they started asking questions: How and why are we being changed? Where did it come from? Is flug good or bad for us? What does it mean? What is the best way to live with it in our air? They too distilled flug, and then tasted and tested it. One would dip his finger into the beaker, taste it, and say, “Hey, this stuff isn’t half bad!” Another would spit out what he had just tasted and say, “Bleah! This stuff isn’t half good!” And, as it turned out, they were both right. They managed to build a microscope to study flug-distillate. They would lean over it for hours, and they could actually see the goodness and the badness of flug, dark and light filaments spreading out like the tendrils of a vine. The problem was, the dark and light filaments were woven and tangled together, so you can imagine how hard and laborious a process it was to disentangle the good strands from the bad. It was all just so mixed together. But still they persevered, for they knew that mixture meant something.

Turnau writes:

This book is for that last group of people, the ones who are interested in taking a closer look at flug. Everything that follows flows from a certain assumption, namely, that popular culture is very similar to the flug in the air we breathe. Popular culture is all around us, and it does tend to get under our skin. It does influence us. Of course, the influence isn’t on our lungs, but on our worldviews – on the way we understand God, the world, each other, and ourselves. And, like flug, popular culture is a mixed bag, a messy mixture of good and bad. Comedian Oliver Hardy used to say to Stan Laurel, “Another fine mess you’ve gotten us into!” Living in a world suffused by popular culture has landed us, quite literally, into a fine, meaningful mess.

You can read some sample pages from the book here.

July 8, 2012

An Interview with Craig Blomberg on Jesus and the Reliability of the Gospels

Craig L. Blomberg, Distinguished Professor of New Testament at Denver Seminary, is one of the most prolific scholars of our day. Among his many books, Historical Reliability of the Gospels is one of the most helpful books ever written on the topic, and his Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey, is the best accessible one-volume resource on this that I know.

Can you tell us a bit about your own personal experience in coming to embrace the historical reliability of the gospels? Was there a period of time in your life when you seriously doubted the historical integrity of the gospel accounts?

I was raised in a fairly liberal branch of the old Lutheran Church in America, before the merger that created today’s ELCA. I vividly remember being very puzzled in confirmation class when I was taught/shown how the Synoptic accounts of the Last Supper contradicted each other as an illustration of how our doctrine of Scripture should focus on the main points and basic thoughts of the text but allow for contradictions in the details. Even in junior high, it seemed to me that there were plausible ways of combining the texts into a harmonious whole and seeing each as a partial excerpt of a larger narrative, but our pastor didn’t countenance that option.

In college, at an LCA school, all five of our religion department professors were ordained Lutheran ministers but not one of them believed that Jesus said or did more than a significant minority of the things attributed to him in the canonical gospels. Our Campus Crusade for Christ director on campus, however, pointed us to a lot of good literature that presented credible scholarly alternatives to the skeptical views on numerous subjects that the religion department promoted. Our college library also included quite a large volume of more conservative religious scholarship from a slightly older era because, until the 1960s it had housed a seminary as well as an undergraduate college, and the real move toward liberalism didn’t hit the Lutherans until the 1960s, just one decade before I was in college. So I realized that things weren’t nearly as cut and dried as I was being taught in class.

I also discovered that a disproportionate number of the more evangelical works of the 1970s, at least among those written in America, came from profs at Trinity in Deerfield, which is one of the main reasons I went there for seminary. That was a wonderful time as I encountered so many more credible responses to skeptical approaches that I had been interacting with in junior high, senior high, and college. And credible evangelical scholarship has only blossomed in pretty amazing quantities ever since.

One can easily find blogs and websites claiming that Jesus never existed. Even if we didn’t have the New Testament, what would we know about Jesus from non-Christian sources?

The best source here for a book-length answer is Robert van Voorst’s Jesus outside the New Testament (Eerdmans, 2000). Here is my composite summary:

Jesus was a first-third of the first-century Jew, who lived in Israel, was born out of wedlock, whose ministry intersected with that of John the Baptist, who became a popular teacher and wonder-worker, who gathered particularly close disciples to himself, five of whom are named (though some of the names are a bit garbled), who consistently taught perspectives on the Law that ran afoul of the religious authorities’ interpretations, who was believed to be the Messiah, who was eventually crucified under Pontius Pilate, Roman procurator in Judea (which enables us to narrow the date for that event to somewhere between A.D. 26 and 36), and who was allegedly seen by many of his followers as bodily resurrected from the dead. Instead of dying out, the movement of his followers continued to grow with each passing decade and within a short period of time people were singing hymns to him as if he were a god.

[Note: See Blomberg's excellent and substantial online essay, "Jesus of Nazareth: How Historians Can Know Him and Why It Matters."]

What are some of the major categories of alleged gospel contradictions?

Theological distinctives, numerical discrepancies, similar events that may actually reflect separate episodes or teachings in his life, partial excerptings from longer events, approximations that would not have been seen as inaccurate by the standards of the day, occasional tensions with extra-biblical data, and the like.

Could you give us a couple of examples of alleged contradictions that have plausible solutions?

Did the centurion come to Jesus right off the bat and ask him for his servant to be healed (as in Matthew 8) or did he first send some Jewish elders as an embassy to ask on his behalf (as in Luke 7)?

Probably, the latter, since to act on behalf of another person could have been reported as acting oneself. We have the same convention when the media report that “the President today announced. . . .” when in fact it was his press secretary.

Did the Sanhedrin condemn Jesus to be sent on to Pilate for execution during a nighttime trial (as in Luke) or first thing after dawn in the morning (as in Matthew and Mark).

Probably both. It was illegal to come to a capital verdict at night, but in the flurry of events and eagerness of the authorities to do away with Jesus, it is hard to imagine them not beginning to interrogate him during the night and come to provisional conclusions. But to create the aura of legality, a quick rubber-stamp formal hearing involving the legal essentials, first thing in the morning, is equally likely.

Let me ask about one in particular, because it has been highlighted by Bart Ehrman as being decisive in his journey from evangelical to agnostic. It began, he says, after writing a graduate paper attempting to harmonize the fact that Mark 2:26 has Jesus saying that David entered the temple to eat the bread of the Presence in the days of Abiathar the high priest—but in point of fact, 1 Samuel 21 clearly says that Ahimelech was the high priest during this episode. How would you respond? Was Jesus mistaken?

The Greek here is very unusual. The construction is a two word prepositional phrase, epi Abiathar, which literally means “upon Abiathar.” Obviously, some kind of idiom is being used. One possibility is “in the days of A.” But in Mark 12:26, Mark uses the same construction, epi tou batou (literally, “upon the bush”) where most translations render it something like “in the account of the bush” or “in the passage about the bush.” This makes very good sense of Mark 2:26 as well. Jesus could very well have been saying, “in the account/passage about Abiathar.”

The next question, then, is what Jews in Jesus’ day would have considered an “account” or “passage.” We tend to think today in terms of fairly small chunks of text, but ancient Jews read all of the Torah annually straight through in weekly synagogue readings and the rest of the Old Testament in a triennial cycle of readings. To do so required multiple chapters to be read during worship each week. Each of these multiple-chapter accounts had names to help identify them, sometimes as short as one word. Often the names were the names of a key character in the text. Unfortunately no list of all the names used for the passages has survived. The only ones we know of are those that are mentioned sporadically in the rabbinic literature in the context of some other kind of discussion. But it is hardly implausible to imagine that Abiathar might have been the name given to a multiple-chapter segment of 1 Samuel that included chapter 21 and the details about Ahimelech, since Abiathar appears in the very next chapter of 1 Samuel and became the better remembered of the two figures in Jewish history. I might add that John Wenham set all of this out in a brief article in the Journal of Theological Studies way back in 1950.

Ehrman, in his introduction to Misquoting Jesus, tells the story of writing a paper at Princeton in which he defended a resolution to this problem, though he doesn’t tell us what it was. It wouldn’t surprise me if it was something along these lines, since the article would already have been well known when he was a student. Ehrman goes on to describe how it was his professor’s response (asking him why he did not just say that Mark made a mistake) that revolutionized his attitude toward Scripture. And it was all down hill for him from there.

There are a lot of things I would like to say in response to Ehrman’s autobiographical reflections. But I’ll limit myself here to saying two things. First, if one was prepared to abandon all pretense of Christian faith on the basis of one apparent error in Scripture, one’s faith must not have amounted to much in the first place. I have no problem with accepting as Christian the approach that allows for minor historical mistakes in the Bible but still acknowledges the main story line. That’s not the approach that I take, but I know far too many solid believers who do opt for such an approach to dismiss it as not an option for a genuine Christian. But second, I wonder what else made Ehrman reject his original paper and/or an approach like Wenham’s. I have yet to hear anyone give me a good reason why it is improbable.

The first edition of The Historical Reliability of the Gospels was published over 25 years ago, and I know that it has been instrumental for many in recovering a basic belief in the reliability of the gospel accounts. The following question might be difficult to answer, but could you give any generalizations about the ways in which perceptions have changed—positively and negatively—in the last 25 years, in the academy, in the pew, and in the marketplace of ideas?

I am very encouraged by most of the developments of the last twenty-five years. Scholars of all stripes far more often engage evangelical scholarship today than they did two decades ago. Whether or not they engage my book directly, they certainly engage many of the writings of the scholars I rely on most heavily. The so-called third quest of the historical Jesus, which really began in earnest in mid-1980s, continues unabated and is strikingly more optimistic about what we can recover from the canonical texts about the historical Jesus. It is a pity that what has dominated the average American’s attention during this period includes primarily the Jesus Seminar (during the 1990s) which was a largely non-representative and idiosyncratic slice of the scholarly world and now increasingly (during this decade) whatever makes it to the Internet rather than whatever represents the best scholarship even if available only in hard copy form.

The democratization of information that the Internet has created is a very mixed blessing. Without the peer-review process that academic publishers require, anybody can say anything, however, outrageously skewed or downright false, and far too many people read Internet publications far too gullibly. Indeed, if I hadn’t written the peer-reviewed works that I have that people can consult, they shouldn’t necessarily be believing me on this blog! Who knows whether I’d be telling the truth or not?

Evangelical scholars have done an outstanding job of producing top-notch books that defend truth. But what role, if any, do you see new media playing in the next phase of the defense of the faith?

In my opinion, the answer has to be both-and. We must continue to publish peer-reviewed works, even if for awhile that still means they will not be Internet accessible. But we must co-operate with each other, even as you and I, Justin, are doing on this blogposting, so that people who ill-advisedly choose not to read anything that can’t be accessed with a split-second Internet connection will find solid scholarship disseminated, and popularized, in the media they are employing.

Tell us a bit about the origins of Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey. Why did you write it, and who is the intended audience?

I had taught a course on the Gospels for almost fifteen years, both at the undergraduate and graduate levels and could not find a single textbook that did something of substance with all five topics that form the five main parts of the volume-historical background, critical methods, introductions to each Gospel individually, a harmony of the life of Christ with selected interpretive commentary, and summaries of the historicity of the Gospels and the theology of Jesus. So I regularly assigned multiple textbooks, even while making my class lecture notes in outline form ever fuller. Eventually I created a spiral-bound notebook in prose as I began to ponder continuing to expand it into a “one-stop shopping” textbook.

It is written for beginning seminarians or upper-division classes for undergraduate Bible majors, but with thoughtful laypersons and busy pastors in view as well. Even the seasoned scholar might stumble across a footnote or bibliography item pointing him or her to a source they were not previously familiar with.

How do you see the Lord using this book to serve the Church?

Inasmuch as many of the people in the categories I just mentioned teach and preach in local churches, or are preparing to, the book can form the core of what they will re-package, supplement, contextualize, and pass on to those among whom they minister. I have had to be selective in my exegetical comments, but I have tried to focus on all the major controversies or questions of which I am aware that tend to emerge in church circles rather than just what academics most like to debate.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers