Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 880

January 28, 2016

Republicans react to a GOP debate without Trump: “Waste. What a freaking waste”

Published on January 28, 2016 21:18

Even without Donald Trump, the GOP debate was fixated on how Americans must live in fear of ISIS

Most of the candidates in the seventh Republican debate, on Fox News, went with the "ignore Trump" strategy to handle his obnoxious (but hilarious) boycotting stunt. But even without him in the room, it's clear that Donald Trump is still controlling the terms of the Republican primary. As with the last debate, this debate quickly devolved into a contest over who could beat Trump at the game of stirring up the most hysteria about the scary Muslims that are coming to destroy the humble Christians that Republican voters imagine themselves to be. Trump, with his proposed ban on Muslims coming into the country, set the bar ridiculously high when it comes to pandering to the hysterics and the bigots. None of the other candidates were willing to go that far, but they did try to make up for it by being the most belligerent and stoking the most irrational fear. Chris Christie and Marco Rubio, in particular, tried to turn every topic to the issue of how ISIS is coming to get you, probably tonight and probably by sneaking in through the air ducts. When asked about his history of changing positions on immigration, Rubio deflected as quickly as he could and pivoted to the question of ISIS. "No. 1, we're going to keep ISIS out of America," he intoned gravely. "If we don't know who you are, or why you're coming, you will not get into the United States," implying that the current immigration policy does not bother itself with such questions. (In reality, the kind of visa or green card status you get depends entirely on things like "who you are" and "why you're coming.") Christie pulled a similar trick when confronted with an uncomfortable question about Kentucky county clerk Kim Davis, and statements he made suggesting, heaven forbid, that bigots shouldn't have unilateral authority to deny gay people constitutionally protected rights. After arguing that he never actually said she should have to do her job, he pivoted to, you guessed it, ISIS.

The radical Islamic jihadists, what they want to do is impose their faith upon each and every one of us -- every one of us. And the reason why this war against them is so important is that very basis of religious liberty. They want everyone in this country to follow their religious beliefs the way they do. They do not want us to exercise religious liberty. That's why as commander in chief, I will take on ISIS, not only because it keeps us safe, but because it allows us to absolutely conduct our religious affairs the way we find in our heart and in our souls.It's true that ISIS wants to force the rest of the world to live by its fanatical interpretation of Islam, I guess. But that's like saying Richard Dawkins would like everyone to give up religion altogether: Technically true, but utterly irrelevant. Does Christie actually think we're in real danger of having our religious liberty stripped as we're forced to live in a medieval caliphate? Is he really worried that we're just a couple of foreign policy missteps away from American churches being forcibly converted to mosques? Does he think his daughters are in real danger of being forced to marry ISIS fighters? The worst part of this is Christie's dog whistling of the bizarre but widespread "sharia law" conspiracy theory still couldn't compete with Rubio's unhinged attempts to convince the voters that the streets are practically overflowing with ISIS fighters as we speak. For instance, this bizarre moment:

Look at the attack they inspired in Philadelphia, that the White House still refuses to link to terror, where a guy basically shot a police officer three times. He told the police, "I did it because I was inspired by ISIS," and to this day, the White House still refuses to acknowledge it had anything to do with terror.That's because the man in question, Edward Archer, is not an ISIS fighter. He appears instead to be a mentally ill man, probably schizophrenic, whose mother says he has been "hearing voices in his head". Suggesting he's a member of ISIS is like calling the mentally ill homeless woman who yelled sexual suggestions at me the other day my boyfriend. All two hours of the debate went down like this, with Ben Carson suggesting we're in danger because we're "allowing political correctness to dictate our policies" and Rubio calling ISIS "the most dangerous jihadist group in the history of mankind", a bit of rhetorical trickery that allows him to imply they're scare than, say, Nazis, while maintaining some kind of plausible deniability. There's a lot of reasons for this ridiculous rhetoric, of course. Republicans have long been fans of the "vote for me or we're all going to die" gambit, as anyone who lived through the Cold War can attest. But the over-the-top silliness is surely due in no small part to Donald Trump. He saw his poll numbers spike by embracing open bigotry against Muslim last month. Now the rest of the candidates feel they have to hustle, and hard, for those voters who believe, or at least enjoy pretending to believe, that we're in imminent danger from a widespread jihadist invasion and that you can't trust anyone with an Arabic last name or who wears a hijab.

Published on January 28, 2016 21:01

Patton Oswalt reimagines GOP candidates’ closing statements: “I’m going to try reciting The Preamble without singing it like I learned on Schoolhouse Rock” — Ben Carson

With Donald Trump absent from the Fox News debate stage tonight, viewers were treated to significantly less verbal jousting and tweetable moments, leaving our favorite #GOPDebate live-tweeter deliriously bored but still plenty funny. In the end, Patton Oswalt imagined his own hilarious closing statements for the Republican presidential candidates: https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat... https://twitter.com/pattonoswalt/stat...

Published on January 28, 2016 20:32

“This is the lie that Ted’s campaign is built on”: Immigration sets off an epic Rubio-Cruz debate and divides conservatives

Midway through the second hour of Fox News' GOP debate, moderator Megyn Kelly presented a video montage of Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and Jeb Bush all appearing to flip-flop on immigration. That's when the gloves finally came off. “You’ve been wiling to say or do anything in order to get votes,” Rubio lashed out at Cruz, setting off an immigration squabble. "This is the lie that Ted's campaign is built on." "Now you want to trump Trump on immigration," Rubio incredulously asked Cruz. "I'm kind of confused because he was the sponsor of the Gang of Eight bill," Bush jumped in, curiously deflecting fire from Cruz to continue his attack on Rubio. “It’s perfectly legal in this country to change your mind,” Chris Christie finally interjected in a weak attempt to return civility to the debate. For conservatives on Twitter, the entire episode played out like bitter family battle: https://twitter.com/RichLowry/status/... https://twitter.com/DanielLarison/sta... https://twitter.com/EWErickson/status... https://twitter.com/michellemalkin/st... https://twitter.com/RalstonReports/st... https://twitter.com/brithume/status/6... https://twitter.com/chicksonright/sta... https://twitter.com/SonnyBunch/status... https://twitter.com/stephenfhayes/sta... https://twitter.com/NoahCRothman/stat... https://twitter.com/SonnyBunch/status... https://twitter.com/charlescwcooke/st... through the second hour of Fox News' GOP debate, moderator Megyn Kelly presented a video montage of Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and Jeb Bush all appearing to flip-flop on immigration. That's when the gloves finally came off. “You’ve been wiling to say or do anything in order to get votes,” Rubio lashed out at Cruz, setting off an immigration squabble. "This is the lie that Ted's campaign is built on." "Now you want to trump Trump on immigration," Rubio incredulously asked Cruz. "I'm kind of confused because he was the sponsor of the Gang of Eight bill," Bush jumped in, curiously deflecting fire from Cruz to continue his attack on Rubio. “It’s perfectly legal in this country to change your mind,” Chris Christie finally interjected in a weak attempt to return civility to the debate. For conservatives on Twitter, the entire episode played out like bitter family battle: https://twitter.com/RichLowry/status/... https://twitter.com/DanielLarison/sta... https://twitter.com/EWErickson/status... https://twitter.com/michellemalkin/st... https://twitter.com/RalstonReports/st... https://twitter.com/brithume/status/6... https://twitter.com/chicksonright/sta... https://twitter.com/SonnyBunch/status... https://twitter.com/stephenfhayes/sta... https://twitter.com/NoahCRothman/stat... https://twitter.com/SonnyBunch/status... https://twitter.com/charlescwcooke/st... through the second hour of Fox News' GOP debate, moderator Megyn Kelly presented a video montage of Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and Jeb Bush all appearing to flip-flop on immigration. That's when the gloves finally came off. “You’ve been wiling to say or do anything in order to get votes,” Rubio lashed out at Cruz, setting off an immigration squabble. "This is the lie that Ted's campaign is built on." "Now you want to trump Trump on immigration," Rubio incredulously asked Cruz. "I'm kind of confused because he was the sponsor of the Gang of Eight bill," Bush jumped in, curiously deflecting fire from Cruz to continue his attack on Rubio. “It’s perfectly legal in this country to change your mind,” Chris Christie finally interjected in a weak attempt to return civility to the debate. For conservatives on Twitter, the entire episode played out like bitter family battle: https://twitter.com/RichLowry/status/... https://twitter.com/DanielLarison/sta... https://twitter.com/EWErickson/status... https://twitter.com/michellemalkin/st... https://twitter.com/RalstonReports/st... https://twitter.com/brithume/status/6... https://twitter.com/chicksonright/sta... https://twitter.com/SonnyBunch/status... https://twitter.com/stephenfhayes/sta... https://twitter.com/NoahCRothman/stat... https://twitter.com/SonnyBunch/status... https://twitter.com/charlescwcooke/st... through the second hour of Fox News' GOP debate, moderator Megyn Kelly presented a video montage of Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz and Jeb Bush all appearing to flip-flop on immigration. That's when the gloves finally came off. “You’ve been wiling to say or do anything in order to get votes,” Rubio lashed out at Cruz, setting off an immigration squabble. "This is the lie that Ted's campaign is built on." "Now you want to trump Trump on immigration," Rubio incredulously asked Cruz. "I'm kind of confused because he was the sponsor of the Gang of Eight bill," Bush jumped in, curiously deflecting fire from Cruz to continue his attack on Rubio. “It’s perfectly legal in this country to change your mind,” Chris Christie finally interjected in a weak attempt to return civility to the debate. For conservatives on Twitter, the entire episode played out like bitter family battle: https://twitter.com/RichLowry/status/... https://twitter.com/DanielLarison/sta... https://twitter.com/EWErickson/status... https://twitter.com/michellemalkin/st... https://twitter.com/RalstonReports/st... https://twitter.com/brithume/status/6... https://twitter.com/chicksonright/sta... https://twitter.com/SonnyBunch/status... https://twitter.com/stephenfhayes/sta... https://twitter.com/NoahCRothman/stat... https://twitter.com/SonnyBunch/status... https://twitter.com/charlescwcooke/st...

Published on January 28, 2016 20:07

Misfires at GOP debate: Jeb Bush, Ted Cruz embarrass themselves while taking shots at Donald Trump

What became immediately clear in the first half hour of the seventh Republican debate, airing on Fox News on Thursday night, was that the candidates weren't going to say anything you haven't heard from all of them before: They are a-scared of terrorists, they like to pretend they are tough, they think they're the only true conservative on stage. Under the circumstances, the only question of interest in how they're going to deal with the orange-haired elephant in the room---or should we say not in the room — Donald Trump. Most of the candidates went with the path of least resistance, which is just ignoring him and going forward with the debate like his previous participation was all a bad dream. This turned out to be the wisest choice, because for the two candidates who gave into the temptation, the experience was so embarrassing that it was hard not to cringe for them. Ted Cruz started off promisingly, using his spot as the first candidate to speak to say, "Now, secondly, let me say I'm a maniac and everyone on this stage is stupid, fat, and ugly. And Ben, you're a terrible surgeon." Big laugh. But then he had to ruin it by explaining the joke. "Now that we've gotten the Donald Trump portion out of the way," he continued, as the laughter turned from genuine to charitable. He then immediately returned to kissing Trump's ass, insisting he doesn't insult the man and that he's "glad Donald is running". This trying-too-hard quality has haunted Cruz's interactions with Trump from day one, and has only grown more peaked in the past 24 hours, as Cruz, with the thirst of a man who's been hiking the Sahara for three days, tried to hijack Trump's debate boycott stunt by demanding a one-on-one debate with Trump. You get the feeling that he just keeps texting Trump and sits there, sadly, waiting for the read receipt so he can get mad that Trump isn't texting back. Not that Jeb Bush was any less awkward. "I kind of miss Donald Trump," he said in his first response to a question. "He was a little teddy bear to me," he added, with visible nervousness. You could see the wheels churning in his head: The aides said that a little irony and self-deprecation would make this go down easier, but can he pull it off? Will the audience understand such elaborate rhetorical tricks? Should he just yell about how everyone else is a "loser" instead? Worry, worry. But lucky for him, Cruz was going to emerge as the clear winner of the Trump-induced gooberery. It quickly became clear that his plan was to Trump's absence to present himself as the new Donald Trump. He complained that "the last four questions" were nothing but invitations to "please attack Ted," obviously trying to imitate Trump's strategy of accusing everyone else of being obsessed with and out to get him. In case you didn't get it, he drove home the wished-for comparison by saying that if the attacks continue, "I may have to leave the stage." "It's a debate, sir," Chris Wallace replied. If it was Trump, he would have grinned and shrugged his shoulders and the crowd would laugh and Wallace's retort would have been successfully deflected. But Cruz, of course, has no skill at this, and instead he ended up just looking like a petulant baby. It turns out that being Donald Trump is not as easy as it looks. What became immediately clear in the first half hour of the seventh Republican debate, airing on Fox News on Thursday night, was that the candidates weren't going to say anything you haven't heard from all of them before: They are a-scared of terrorists, they like to pretend they are tough, they think they're the only true conservative on stage. Under the circumstances, the only question of interest in how they're going to deal with the orange-haired elephant in the room---or should we say not in the room — Donald Trump. Most of the candidates went with the path of least resistance, which is just ignoring him and going forward with the debate like his previous participation was all a bad dream. This turned out to be the wisest choice, because for the two candidates who gave into the temptation, the experience was so embarrassing that it was hard not to cringe for them. Ted Cruz started off promisingly, using his spot as the first candidate to speak to say, "Now, secondly, let me say I'm a maniac and everyone on this stage is stupid, fat, and ugly. And Ben, you're a terrible surgeon." Big laugh. But then he had to ruin it by explaining the joke. "Now that we've gotten the Donald Trump portion out of the way," he continued, as the laughter turned from genuine to charitable. He then immediately returned to kissing Trump's ass, insisting he doesn't insult the man and that he's "glad Donald is running". This trying-too-hard quality has haunted Cruz's interactions with Trump from day one, and has only grown more peaked in the past 24 hours, as Cruz, with the thirst of a man who's been hiking the Sahara for three days, tried to hijack Trump's debate boycott stunt by demanding a one-on-one debate with Trump. You get the feeling that he just keeps texting Trump and sits there, sadly, waiting for the read receipt so he can get mad that Trump isn't texting back. Not that Jeb Bush was any less awkward. "I kind of miss Donald Trump," he said in his first response to a question. "He was a little teddy bear to me," he added, with visible nervousness. You could see the wheels churning in his head: The aides said that a little irony and self-deprecation would make this go down easier, but can he pull it off? Will the audience understand such elaborate rhetorical tricks? Should he just yell about how everyone else is a "loser" instead? Worry, worry. But lucky for him, Cruz was going to emerge as the clear winner of the Trump-induced gooberery. It quickly became clear that his plan was to Trump's absence to present himself as the new Donald Trump. He complained that "the last four questions" were nothing but invitations to "please attack Ted," obviously trying to imitate Trump's strategy of accusing everyone else of being obsessed with and out to get him. In case you didn't get it, he drove home the wished-for comparison by saying that if the attacks continue, "I may have to leave the stage." "It's a debate, sir," Chris Wallace replied. If it was Trump, he would have grinned and shrugged his shoulders and the crowd would laugh and Wallace's retort would have been successfully deflected. But Cruz, of course, has no skill at this, and instead he ended up just looking like a petulant baby. It turns out that being Donald Trump is not as easy as it looks. What became immediately clear in the first half hour of the seventh Republican debate, airing on Fox News on Thursday night, was that the candidates weren't going to say anything you haven't heard from all of them before: They are a-scared of terrorists, they like to pretend they are tough, they think they're the only true conservative on stage. Under the circumstances, the only question of interest in how they're going to deal with the orange-haired elephant in the room---or should we say not in the room — Donald Trump. Most of the candidates went with the path of least resistance, which is just ignoring him and going forward with the debate like his previous participation was all a bad dream. This turned out to be the wisest choice, because for the two candidates who gave into the temptation, the experience was so embarrassing that it was hard not to cringe for them. Ted Cruz started off promisingly, using his spot as the first candidate to speak to say, "Now, secondly, let me say I'm a maniac and everyone on this stage is stupid, fat, and ugly. And Ben, you're a terrible surgeon." Big laugh. But then he had to ruin it by explaining the joke. "Now that we've gotten the Donald Trump portion out of the way," he continued, as the laughter turned from genuine to charitable. He then immediately returned to kissing Trump's ass, insisting he doesn't insult the man and that he's "glad Donald is running". This trying-too-hard quality has haunted Cruz's interactions with Trump from day one, and has only grown more peaked in the past 24 hours, as Cruz, with the thirst of a man who's been hiking the Sahara for three days, tried to hijack Trump's debate boycott stunt by demanding a one-on-one debate with Trump. You get the feeling that he just keeps texting Trump and sits there, sadly, waiting for the read receipt so he can get mad that Trump isn't texting back. Not that Jeb Bush was any less awkward. "I kind of miss Donald Trump," he said in his first response to a question. "He was a little teddy bear to me," he added, with visible nervousness. You could see the wheels churning in his head: The aides said that a little irony and self-deprecation would make this go down easier, but can he pull it off? Will the audience understand such elaborate rhetorical tricks? Should he just yell about how everyone else is a "loser" instead? Worry, worry. But lucky for him, Cruz was going to emerge as the clear winner of the Trump-induced gooberery. It quickly became clear that his plan was to Trump's absence to present himself as the new Donald Trump. He complained that "the last four questions" were nothing but invitations to "please attack Ted," obviously trying to imitate Trump's strategy of accusing everyone else of being obsessed with and out to get him. In case you didn't get it, he drove home the wished-for comparison by saying that if the attacks continue, "I may have to leave the stage." "It's a debate, sir," Chris Wallace replied. If it was Trump, he would have grinned and shrugged his shoulders and the crowd would laugh and Wallace's retort would have been successfully deflected. But Cruz, of course, has no skill at this, and instead he ended up just looking like a petulant baby. It turns out that being Donald Trump is not as easy as it looks.

Published on January 28, 2016 19:24

Donald Trump insults the very veterans he’s speaking to: “We don’t win at the military anymore”

During Donald Trump's "Special Event for Veterans," Trump couldn't help but introduce a little campaign rhetoric into his celebration of the armed forces. "We need to make our military so big, so powerful, we never have to use it. I see generals on television who are retired, but they're all talking," he said. "I want generals who want action," he added, apparently unaware that he was directly contradicting what he'd said all of twenty seconds earlier. "I want General Pattons, I want General MacArthurs," Trump continued, "I want people who are going to keep up safe. So I just say this, we're a country that doesn't win anymore. We don't win on trade, we don't win at the military, we don't beat ISIS." "We don't do anything -- we're not good." But if Trump's elected, "we're going to get used to winning again. We're going to win at the military, we're going to win at the border, we're going to win on trade." "We are going to win again -- at every single level -- and we're not going to be laughed at by the rest of the world, and believe me, they laugh at our stupidity." Trump launched into a story about sending weapons to allies overseas, and having to listen to members of the armed forces tell him that "they have the new versions of the weapons we use, they have the best weapons -- the enemy." He also obliquely addressed claims that the Donald J. Trump Foundation has not lived up to its promise to support veterans by saying there was "a list of organizations we're donating too outside, and we picked ones with heart, because the heart is so important."During Donald Trump's "Special Event for Veterans," Trump couldn't help but introduce a little campaign rhetoric into his celebration of the armed forces. "We need to make our military so big, so powerful, we never have to use it. I see generals on television who are retired, but they're all talking," he said. "I want generals who want action," he added, apparently unaware that he was directly contradicting what he'd said all of twenty seconds earlier. "I want General Pattons, I want General MacArthurs," Trump continued, "I want people who are going to keep up safe. So I just say this, we're a country that doesn't win anymore. We don't win on trade, we don't win at the military, we don't beat ISIS." "We don't do anything -- we're not good." But if Trump's elected, "we're going to get used to winning again. We're going to win at the military, we're going to win at the border, we're going to win on trade." "We are going to win again -- at every single level -- and we're not going to be laughed at by the rest of the world, and believe me, they laugh at our stupidity." Trump launched into a story about sending weapons to allies overseas, and having to listen to members of the armed forces tell him that "they have the new versions of the weapons we use, they have the best weapons -- the enemy." He also obliquely addressed claims that the Donald J. Trump Foundation has not lived up to its promise to support veterans by saying there was "a list of organizations we're donating too outside, and we picked ones with heart, because the heart is so important."During Donald Trump's "Special Event for Veterans," Trump couldn't help but introduce a little campaign rhetoric into his celebration of the armed forces. "We need to make our military so big, so powerful, we never have to use it. I see generals on television who are retired, but they're all talking," he said. "I want generals who want action," he added, apparently unaware that he was directly contradicting what he'd said all of twenty seconds earlier. "I want General Pattons, I want General MacArthurs," Trump continued, "I want people who are going to keep up safe. So I just say this, we're a country that doesn't win anymore. We don't win on trade, we don't win at the military, we don't beat ISIS." "We don't do anything -- we're not good." But if Trump's elected, "we're going to get used to winning again. We're going to win at the military, we're going to win at the border, we're going to win on trade." "We are going to win again -- at every single level -- and we're not going to be laughed at by the rest of the world, and believe me, they laugh at our stupidity." Trump launched into a story about sending weapons to allies overseas, and having to listen to members of the armed forces tell him that "they have the new versions of the weapons we use, they have the best weapons -- the enemy." He also obliquely addressed claims that the Donald J. Trump Foundation has not lived up to its promise to support veterans by saying there was "a list of organizations we're donating too outside, and we picked ones with heart, because the heart is so important."During Donald Trump's "Special Event for Veterans," Trump couldn't help but introduce a little campaign rhetoric into his celebration of the armed forces. "We need to make our military so big, so powerful, we never have to use it. I see generals on television who are retired, but they're all talking," he said. "I want generals who want action," he added, apparently unaware that he was directly contradicting what he'd said all of twenty seconds earlier. "I want General Pattons, I want General MacArthurs," Trump continued, "I want people who are going to keep up safe. So I just say this, we're a country that doesn't win anymore. We don't win on trade, we don't win at the military, we don't beat ISIS." "We don't do anything -- we're not good." But if Trump's elected, "we're going to get used to winning again. We're going to win at the military, we're going to win at the border, we're going to win on trade." "We are going to win again -- at every single level -- and we're not going to be laughed at by the rest of the world, and believe me, they laugh at our stupidity." Trump launched into a story about sending weapons to allies overseas, and having to listen to members of the armed forces tell him that "they have the new versions of the weapons we use, they have the best weapons -- the enemy." He also obliquely addressed claims that the Donald J. Trump Foundation has not lived up to its promise to support veterans by saying there was "a list of organizations we're donating too outside, and we picked ones with heart, because the heart is so important."

Published on January 28, 2016 19:20

6 national security questions we should be asking our presidential candidates

To judge by the early returns, the presidential race of 2016 is shaping up as the most disheartening in recent memory. Other than as a form of low entertainment, the speeches, debates, campaign events, and slick TV ads already inundating the public sphere offer little of value. Rather than exhibiting the vitality of American democracy, they testify to its hollowness. Present-day Iranian politics may actually possess considerably more substance than our own. There, the parties involved, whether favoring change or opposing it, understand that the issues at stake have momentous implications. Here, what passes for national politics is a form of exhibitionism about as genuine as pro wrestling. A presidential election campaign ought to involve more than competing coalitions of interest groups or bevies of investment banks and billionaires vying to install their preferred candidate in the White House. It should engage and educate citizens, illuminating issues and subjecting alternative solutions to careful scrutiny. That this one won’t even come close we can ascribe as much to the media as to those running for office, something the recent set of “debates” and the accompanying commentary have made painfully clear. With certain honorable exceptions such as NBC’s estimable Lester Holt, representatives of the press are less interested in fulfilling their civic duty than promoting themselves as active participants in the spectacle. They bait, tease, and strut. Then they subject the candidates’ statements and misstatements to minute deconstruction. The effect is to inflate their own importance while trivializing the proceedings they are purportedly covering. Above all in the realm of national security, election 2016 promises to be not just a missed opportunity but a complete bust. Recent efforts to exercise what people in Washington like to call "global leadership” have met with many more failures and disappointments than clearcut successes. So you might imagine that reviewing the scorecard would give the current raft of candidates, Republican and Democratic alike, plenty to talk about. But if you thought that, you’d be mistaken. Instead of considered discussion of first-order security concerns, the candidates have regularly opted for bluff and bluster, their chief aim being to remove all doubts regarding their hawkish bona fides. In that regard, nothing tops rhetorically beating up on the so-called Islamic State. So, for example, Hillary Clinton promises to “smash the would-be caliphate,” Jeb Bush to “defeat ISIS for good,” Ted Cruz to “carpet bombthem into oblivion,” and Donald Trump to “bomb the shit out of them.” For his part, having recently acquired a gun as the “last line of defense between ISIS and my family,” Marco Rubio insists that when he becomes president, “The most powerful intelligence agency in the world is going to tell us where [ISIS militants] are; the most powerful military in the world is going to destroy them; and if we capture any of them alive, they are getting a one-way ticket to Guantanamo Bay.” These carefully scripted lines perform their intended twofold function. First, they elicit applause and certify the candidate as plenty tough. Second, they spare the candidate from having to address matters far more deserving of presidential attention than managing the fight against the Islamic State. In the hierarchy of challenges facing the United States today, ISIS ranks about on a par with Sicily back in 1943. While liberating that island was a necessary prelude to liberating Europe more generally, the German occupation of Sicily did not pose a direct threat to the Allied cause. So with far weightier matters to attend to -- handling Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, for example -- President Franklin Roosevelt wisely left the problem of Sicily to subordinates. FDR thereby demonstrated an aptitude for distinguishing between the genuinely essential and the merely important. By comparison, today’s crop of presidential candidates either are unable to grasp, cannot articulate, or choose to ignore those matters that shouldrightfully fall under a commander-in-chief’s purview. Instead, they compete with one another in vowing to liberate the twenty-first-century equivalent of Sicily, as if doing so demonstrates their qualifications for the office. What sort of national security concerns should be front and center in the current election cycle? While conceding that a reasoned discussion of heavily politicized matters like climate change, immigration, or anything to do with Israel is probably impossible, other issues of demonstrable significance deserve attention. What follows are six of them -- by no means an exhaustive list -- that I’ve framed as questions a debate moderator might ask of anyone seeking the presidency, along with brief commentaries explaining why neither the posing nor the answering of such questions is likely to happen anytime soon.

1. The War on Terror:

Nearly 15 years after this “war” was launched by George W. Bush, why hasn’t “the

most powerful military

in the world,” “the

finest fighting force

in the history of the world” won it? Why isn’t victory anywhere in sight? As if by informal agreement, the candidates and the journalists covering the race have chosen to ignore the military enterprise inaugurated in 2001, initially called the Global War on Terrorism and continuing today without an agreed-upon name. Since 9/11, the United States has invaded, occupied, bombed, raided, or otherwise established a military presence in numerouscountries across much of the Islamic world. How are we doing? Given the resources expended and the lives lost or ruined, not particularly well it would seem. Intending to promote stability, reduce the incidence of jihadism, and reverse the tide of anti-Americanism among many Muslims, that “war” has done just the opposite. Advance the cause of democracy and human rights? Make that zero-for-four. Amazingly, this disappointing record has been almost entirely overlooked in the campaign. The reasons why are not difficult to discern. First and foremost, both parties share in the serial failures of U.S. policy in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya, and elsewhere in the region. Pinning the entire mess on George W. Bush is no more persuasive than pinning it all on Barack Obama. An intellectually honest accounting would require explanations that look beyond reflexive partisanship. Among the matters deserving critical scrutiny is Washington’s persistent bipartisan belief in military might as an all-purpose problem solver. Not far behind should come questions about simple military competence that no American political figure of note or mainstream media outlet has the gumption to address. The politically expedient position indulged by the media is to sidestep such concerns in favor of offering endless testimonials to the bravery and virtue of the troops, while calling for yet more of the same or even further escalation. Making a show of supporting the troops takes precedence over serious consideration of what they are continually being asked to do. 2.

Nuclear Weapons:

Today, more than 70 years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, what purpose do nukes serve? How many nuclear weapons and delivery systems does the United States actually need? In an initiative that has attracted remarkably little public attention, the Obama administration has announced plans to modernize and upgrade the U.S. nuclear arsenal. Estimated costs of this program reach as high as $1 trillion over the next three decades. Once finished -- probably just in time for the 100th anniversary of Hiroshima -- the United States will possess more flexible, precise, survivable, and therefore usable nuclear capabilities than anything hitherto imagined. In effect, the country will have acquired a first-strike capability -- even as U.S. officials continue to affirm their earnest hope of removing the scourge of nuclear weapons from the face of the Earth (other powers being the first to disarm, of course). Whether, in the process, the United States will become more secure or whether there might be far wiser ways to spend that kind of money -- shoring up cyber defenses, for example -- would seem like questions those who could soon have their finger on the nuclear button might want to consider. Yet we all know that isn’t going to happen. Having departed from the sphere of politics or strategy, nuclear policy has long since moved into the realm of theology. Much as the Christian faith derives from a belief in a Trinity consisting of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, so nuclear theology has its own Triad, comprised of manned bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and submarine-launched missiles. To question the existence of such a holy threesome constitutes rank heresy. It’s just not done -- especially when there’s all that money about to be dropped into the collection plate.

3.

Energy Security:

Given the availability of abundant oil and natural gas reserves in the Western Hemisphere and the potential future abundance of alternative energy systems, why should the Persian Gulf continue to qualify as a vital U.S. national security interest? Back in 1980, two factors prompted President Jimmy Carter to announce that the United States viewed the Persian Gulf as worth fighting for. The first was a growing U.S. dependence on foreign oil and a belief that American consumers were guzzling gas at a rate that would rapidly deplete domestic reserves. The second was a concern that, having just invaded Afghanistan, the Soviet Union might next have an appetite for going after those giant gas stations in the Gulf, Iran, or even Saudi Arabia. Today we know that the Western Hemisphere contains more than ample supplies of oil and natural gas to sustain the American way of life (while also heating up the planet). As for the Soviet Union, it no longer exists -- a decade spent chewing on Afghanistan having produced a fatal case of indigestion. No doubt ensuring U.S. energy security should remain a major priority. Yet in that regard, protecting Canada, Mexico, and Venezuela is far more relevant to the nation’s well-being than protecting Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iraq, while being far easier and cheaper to accomplish. So who will be the first presidential candidate to call for abrogating the Carter Doctrine? Show of hands, please?

4.

Assassination

: Now that the United States has normalized assassination as an instrument of policy, how well is it working? What are its benefits and costs? George W. Bush’s administration pioneered the practice of using missile-armed drones as a method of extrajudicial killing. Barack Obama’s administration greatly expanded and routinized the practice. The technique is clearly “effective” in the narrow sense of liquidating leaders and “lieutenants” of terror groups that policymakers want done away with. What’s less clear is whether the benefits of state-sponsored assassination outweigh the costs, which are considerable. The incidental killing of noncombatants provokes ire directed against the United States and provides terror groups with an excellent recruiting tool. The removal of Mr. Bad Actor from the field adversely affects the organization he leads for no longer than it takes for a successor to emerge. As often as not, the successor turns out to be nastier than Mr. Bad Actor himself. It would be naïve to expect presidential candidates to interest themselves in the moral implications of assassination as now practiced on a regular basis from the White House. Still, shouldn’t they at least wonder whether it actually works as advertised? And as drone technology proliferates, shouldn’t they also contemplate the prospect of others -- say, Russians, Chinese, and Iranians -- following America’s lead and turning assassination into a global practice?

5.

Europe:

Seventy years after World War II and a quarter-century after the Cold War ended, why does European security remain an American responsibility? Given that Europeans are rich enough to defend themselves, why shouldn’t they? Americans love Europe: old castles, excellent cuisine, and cultural attractions galore. Once upon a time, the parts of Europe that Americans love best needed protection. Devastated by World War II, Western Europe faced in the Soviet Union a threat that it could not handle alone. In a singular act of generosity laced with self-interest, Washington came to the rescue. By forming NATO, the United States committed itself to defend its impoverished and vulnerable European allies. Over time this commitment enabled France, Great Britain, West Germany, and other nearby countries to recover from the global war and become strong, prosperous, and democratic countries. Today Europe is “whole and free,” incorporating not only most of the former Soviet empire, but even parts of the old Soviet Union itself. In place of the former Soviet threat, there is Vladimir Putin, a bully governing a rickety energy state that, media hype notwithstanding, poses no more than a modest danger to Europe itself. Collectively, the European Union’s economy, at $18 trillion, equals that of the United States and exceeds Russia’s, even in sunnier times, by a factor of nine. Its total population, easily outnumbering our own, is more than triple Russia’s. What these numbers tell us is that Europe is entirely capable of funding and organizing its own defense if it chooses to do so. It chooses otherwise, in effect opting for something approximating disarmament. As a percentage of the gross domestic product, European nations spend a fraction of what the United States does on defense. When it comes to armaments, they prefer to be free riders and Washington indulges that choice. So even today, seven decades after World War II ended, U.S. forces continue to garrison Europe and America’s obligation to defend 26 countries on the far side of the Atlantic remains intact. The persistence of this anomalous situation deserves election-year attention for one very important reason. It gets to the question of whether the United States can ever declare mission accomplished. Since the end of World War II, Washington has extended its security umbrella to cover not only Europe, but also virtually all of Latin America and large parts of East Asia. More recently, the Middle East, Central Asia, and now Africa have come in for increased attention. Today, U.S. forces alone maintain an active presence in147 countries. Do our troops ever really get to “come home”? The question is more than theoretical in nature. To answer it is to expose the real purpose of American globalism, which means, of course, that none of the candidates will touch it with a 10-foot pole.

6.

Debt:

Does the national debt constitute a threat to national security? If so, what are some politically plausible ways of reining it in? Together, the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama can take credit for tripling the national debt since 2000. Well before Election Day this coming November, the total debt, now exceeding the entire gross domestic product, will breach the $19 trillion mark. In 2010, Admiral Mike Mullen, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff,described that debt as “the most significant threat to our national security.” Although in doing so he wandered a bit out of his lane, he performed a rare and useful service by drawing a link between long-term security and fiscal responsibility. Ever so briefly, a senior military officer allowed consideration of the national interest to take precedence over the care and feeding of the military-industrial complex. It didn’t last long. Mullen’s comment garnered a bit of attention, but failed to spur any serious congressional action. Again, we can see why, since Congress functions as an unindicted co-conspirator in the workings of that lucrative collaboration. Returning to anything like a balanced budget would require legislators to make precisely the sorts of choices that they are especially loathe to make -- cutting military programs that line the pockets of donors and provide jobs for constituents. (Although the F-35 fighter may be one of the most bloated andexpensive weapons programs in history, even Democratic Socialist Senator Bernie Sanders has left no stone unturned in lobbying to get those planes stationed in his hometown of Burlington.) Recently, the role of Congress in authorizing an increase in the debt ceiling has provided Republicans with an excuse for political posturing, laying responsibility for all that red ink entirely at the feet of President Obama -- this despite the fact that he has reduced the annual deficit by two-thirds, from $1.3 trillion the year he took office to $439 billion last year. This much is certain: regardless of who takes the prize in November, the United States will continue to accumulate debt at a non-trivial rate. If a Democrat occupies the White House, Republicans will pretend to care. If our next president is a Republican, they will keep mum. In either case, the approach to national security that does so much to keep the books out of balance will remain intact. Come to think of it, averting real change might just be the one point on which the candidates generally agree.

Published on January 28, 2016 00:45

Bernie on the brink: The latest New Hampshire numbers reveal a national trend

Published on January 28, 2016 00:15

Bernie isn’t a real radical — and that’s precisely why he should support reparations

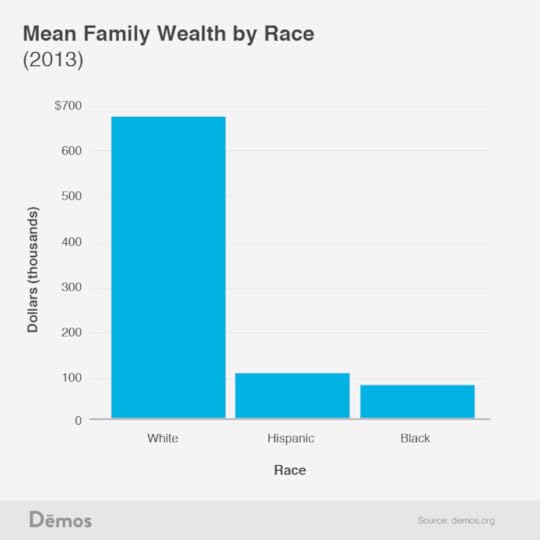

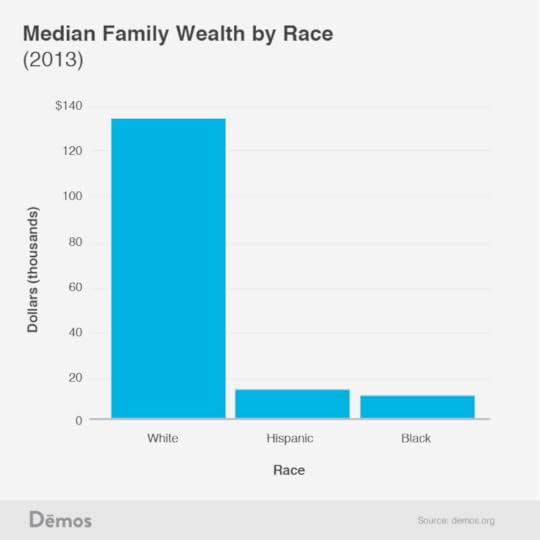

Ta-Nehisi Coates has set off another discussion of reparations, this time in reference to Bernie Sanders opposing them: For those of us interested in how the left prioritizes its various radicalisms, Sanders’s answer is illuminating. The spectacle of a socialist candidate opposing reparations as “divisive” (there are few political labels more divisive in the minds of Americans than socialist) is only rivaled by the implausibility of Sanders posing as a pragmatist. I've written often about the racial wealth gap and why reparations are necessary to close it (I, II, III).

Ta-Nehisi Coates has set off another discussion of reparations, this time in reference to Bernie Sanders opposing them: For those of us interested in how the left prioritizes its various radicalisms, Sanders’s answer is illuminating. The spectacle of a socialist candidate opposing reparations as “divisive” (there are few political labels more divisive in the minds of Americans than socialist) is only rivaled by the implausibility of Sanders posing as a pragmatist. I've written often about the racial wealth gap and why reparations are necessary to close it (I, II, III).

In short, wealth is a stock that builds up over time and is passed down generations. Even if you could snap your fingers and make everything non-racist going forward, you'd still have wealth disparities owing to prior injustices. With that said, I think Coates is a bit muddled when it comes to the political valence of reparations. Although it seems to be sociologically true that reparations has the most purchase among rank-and-file people with left-wing economic views, philosophically speaking, it is much more of a liberal project. Socialism's Confusing Relationship With Reparations There are three basic issues with incorporating reparations into a truly hardline socialist view. First, hardline socialists believe that the plunder of working people is ongoing. Every year, around 30% of what's produced by workers in this country is paid out to owners of capital who did not work for it. The share of the national income going to capital is described by socialists as having been coercively extracted from workers through property relations created and enforced by the government. These days, few socialists would say that the plight of the worker is anywhere near as brutal as the plight of slaves. But on a strict reparations-for-plundered-wealth type rationale, they would be committed to believing that most working people in this country are being plundered right now and have been for centuries. If you run back the tape for all capital income, you'd find that the reparations owed to non-slave workers likely even exceeds those owed to slaves (again under a socialist-type framework). Second, hardline socialists do not generally believe that distributive entitlement is based on productivity. This poses a slight technical problem as reparation amounts are generally calculated accoding to estimates of slave productivity, with the implicit assumption being that people are owed what they produce. I say this is a slight technical problem because it mainly pertains to the calculation of reparations. The problem can be easily avoided by understanding reparations as compensation for an enormous crime rather than compensation for labor. This crime-based theory of reparations is how most reparations have worked, including reparations for victims of Japanese internment. Third, hardline socialists generally believe that basically all wealth should be owned collectively (certainly big assets that make up the bulk of the national wealth). Reparations generally envisions a transfer of private white wealth to private black wealth. But, hardline socialists don't really believe there should be any private wealth. To be sure, moving private wealth into a collective pot would be a huge net swing (in a sense) to those who currently lack much wealth (including Blacks). But it seems that, for some at least, moves that "disproportionately benefit" Blacks don't count as true reparations. There has to be something above and beyond that. Libertarian-ish Idea Philosophically speaking, reparations of the type normally discussed tends to sit the best with libertarian-type reasoning. Indeed, libertarian Robert Nozick famously endorsed reparations in his opus Anarchy, State, Utopia. Reparations finds a more natural home in "voluntarist" type libertarianism because adherents to that view describe plunder as flowing from so-called "involuntary" transactions. They don't view capital's share of the national income as plunder like socialists do (even though it is unearned in the sense that it is not labored for). And they endorse the idea that distributive entitlement flows purely from the fact that you obtained whatever you have through so-called "voluntary" means. So from there, it's easy enough to say that, at least in theory, where wealth is gotten through "involuntary" acts (such as those involved in slavery), then you should right that wrong by transferring the wealth from the plunderer to the plundered. Once that is done, then the injustice created by the deviation from voluntarism is seen as cured, and laissez-faire anarcho-capitalist governance can continue on. Moot for Sanders Although this is a fun philosophical discussion, it is actually somewhat moot when it comes to Sanders. But this is precisely because he's not really a hardline socialist. He should come out for reparations. Nothing about his own political philosophy commitments, which tend to be of the liberal social democratic variety, should make reparations a complicated issue for him. But my point here is that, contrary to Coates' suggestion, Sanders is well-situated to seamlessly come out for reparations because he's not terribly radical. Reparations fits most cleanly within broadly liberal (and capitalist) conceptions of private ownership and broadly liberal (and capitalist) notions that distributive entitlement flows from some mix of "voluntary" transactions and personal productivity. Those who profess radical leftist critiques of these economic ideas actually tend to have the hardest time fitting reparations into their overall economic scheme. Put bluntly: you can't collectivize all the wealth and reparate it out privately at the same time. Ultimately, even those with hardline socialist views don't have much of a practical reason to oppose reparations in the near term, even if is philosophically at odds with their ideal socialist system. Surely a more egalitarian distribution of wealth (in the Rawlsian "property-owning democracy" vein) is a grade better than what we have now even if it is not snap socialization. And reparations works towards that end while also possibly salving a historical crime whose economic and noneconomic effects are still painfully with us.

In short, wealth is a stock that builds up over time and is passed down generations. Even if you could snap your fingers and make everything non-racist going forward, you'd still have wealth disparities owing to prior injustices. With that said, I think Coates is a bit muddled when it comes to the political valence of reparations. Although it seems to be sociologically true that reparations has the most purchase among rank-and-file people with left-wing economic views, philosophically speaking, it is much more of a liberal project. Socialism's Confusing Relationship With Reparations There are three basic issues with incorporating reparations into a truly hardline socialist view. First, hardline socialists believe that the plunder of working people is ongoing. Every year, around 30% of what's produced by workers in this country is paid out to owners of capital who did not work for it. The share of the national income going to capital is described by socialists as having been coercively extracted from workers through property relations created and enforced by the government. These days, few socialists would say that the plight of the worker is anywhere near as brutal as the plight of slaves. But on a strict reparations-for-plundered-wealth type rationale, they would be committed to believing that most working people in this country are being plundered right now and have been for centuries. If you run back the tape for all capital income, you'd find that the reparations owed to non-slave workers likely even exceeds those owed to slaves (again under a socialist-type framework). Second, hardline socialists do not generally believe that distributive entitlement is based on productivity. This poses a slight technical problem as reparation amounts are generally calculated accoding to estimates of slave productivity, with the implicit assumption being that people are owed what they produce. I say this is a slight technical problem because it mainly pertains to the calculation of reparations. The problem can be easily avoided by understanding reparations as compensation for an enormous crime rather than compensation for labor. This crime-based theory of reparations is how most reparations have worked, including reparations for victims of Japanese internment. Third, hardline socialists generally believe that basically all wealth should be owned collectively (certainly big assets that make up the bulk of the national wealth). Reparations generally envisions a transfer of private white wealth to private black wealth. But, hardline socialists don't really believe there should be any private wealth. To be sure, moving private wealth into a collective pot would be a huge net swing (in a sense) to those who currently lack much wealth (including Blacks). But it seems that, for some at least, moves that "disproportionately benefit" Blacks don't count as true reparations. There has to be something above and beyond that. Libertarian-ish Idea Philosophically speaking, reparations of the type normally discussed tends to sit the best with libertarian-type reasoning. Indeed, libertarian Robert Nozick famously endorsed reparations in his opus Anarchy, State, Utopia. Reparations finds a more natural home in "voluntarist" type libertarianism because adherents to that view describe plunder as flowing from so-called "involuntary" transactions. They don't view capital's share of the national income as plunder like socialists do (even though it is unearned in the sense that it is not labored for). And they endorse the idea that distributive entitlement flows purely from the fact that you obtained whatever you have through so-called "voluntary" means. So from there, it's easy enough to say that, at least in theory, where wealth is gotten through "involuntary" acts (such as those involved in slavery), then you should right that wrong by transferring the wealth from the plunderer to the plundered. Once that is done, then the injustice created by the deviation from voluntarism is seen as cured, and laissez-faire anarcho-capitalist governance can continue on. Moot for Sanders Although this is a fun philosophical discussion, it is actually somewhat moot when it comes to Sanders. But this is precisely because he's not really a hardline socialist. He should come out for reparations. Nothing about his own political philosophy commitments, which tend to be of the liberal social democratic variety, should make reparations a complicated issue for him. But my point here is that, contrary to Coates' suggestion, Sanders is well-situated to seamlessly come out for reparations because he's not terribly radical. Reparations fits most cleanly within broadly liberal (and capitalist) conceptions of private ownership and broadly liberal (and capitalist) notions that distributive entitlement flows from some mix of "voluntary" transactions and personal productivity. Those who profess radical leftist critiques of these economic ideas actually tend to have the hardest time fitting reparations into their overall economic scheme. Put bluntly: you can't collectivize all the wealth and reparate it out privately at the same time. Ultimately, even those with hardline socialist views don't have much of a practical reason to oppose reparations in the near term, even if is philosophically at odds with their ideal socialist system. Surely a more egalitarian distribution of wealth (in the Rawlsian "property-owning democracy" vein) is a grade better than what we have now even if it is not snap socialization. And reparations works towards that end while also possibly salving a historical crime whose economic and noneconomic effects are still painfully with us.

Ta-Nehisi Coates has set off another discussion of reparations, this time in reference to Bernie Sanders opposing them: For those of us interested in how the left prioritizes its various radicalisms, Sanders’s answer is illuminating. The spectacle of a socialist candidate opposing reparations as “divisive” (there are few political labels more divisive in the minds of Americans than socialist) is only rivaled by the implausibility of Sanders posing as a pragmatist. I've written often about the racial wealth gap and why reparations are necessary to close it (I, II, III).

Ta-Nehisi Coates has set off another discussion of reparations, this time in reference to Bernie Sanders opposing them: For those of us interested in how the left prioritizes its various radicalisms, Sanders’s answer is illuminating. The spectacle of a socialist candidate opposing reparations as “divisive” (there are few political labels more divisive in the minds of Americans than socialist) is only rivaled by the implausibility of Sanders posing as a pragmatist. I've written often about the racial wealth gap and why reparations are necessary to close it (I, II, III).

In short, wealth is a stock that builds up over time and is passed down generations. Even if you could snap your fingers and make everything non-racist going forward, you'd still have wealth disparities owing to prior injustices. With that said, I think Coates is a bit muddled when it comes to the political valence of reparations. Although it seems to be sociologically true that reparations has the most purchase among rank-and-file people with left-wing economic views, philosophically speaking, it is much more of a liberal project. Socialism's Confusing Relationship With Reparations There are three basic issues with incorporating reparations into a truly hardline socialist view. First, hardline socialists believe that the plunder of working people is ongoing. Every year, around 30% of what's produced by workers in this country is paid out to owners of capital who did not work for it. The share of the national income going to capital is described by socialists as having been coercively extracted from workers through property relations created and enforced by the government. These days, few socialists would say that the plight of the worker is anywhere near as brutal as the plight of slaves. But on a strict reparations-for-plundered-wealth type rationale, they would be committed to believing that most working people in this country are being plundered right now and have been for centuries. If you run back the tape for all capital income, you'd find that the reparations owed to non-slave workers likely even exceeds those owed to slaves (again under a socialist-type framework). Second, hardline socialists do not generally believe that distributive entitlement is based on productivity. This poses a slight technical problem as reparation amounts are generally calculated accoding to estimates of slave productivity, with the implicit assumption being that people are owed what they produce. I say this is a slight technical problem because it mainly pertains to the calculation of reparations. The problem can be easily avoided by understanding reparations as compensation for an enormous crime rather than compensation for labor. This crime-based theory of reparations is how most reparations have worked, including reparations for victims of Japanese internment. Third, hardline socialists generally believe that basically all wealth should be owned collectively (certainly big assets that make up the bulk of the national wealth). Reparations generally envisions a transfer of private white wealth to private black wealth. But, hardline socialists don't really believe there should be any private wealth. To be sure, moving private wealth into a collective pot would be a huge net swing (in a sense) to those who currently lack much wealth (including Blacks). But it seems that, for some at least, moves that "disproportionately benefit" Blacks don't count as true reparations. There has to be something above and beyond that. Libertarian-ish Idea Philosophically speaking, reparations of the type normally discussed tends to sit the best with libertarian-type reasoning. Indeed, libertarian Robert Nozick famously endorsed reparations in his opus Anarchy, State, Utopia. Reparations finds a more natural home in "voluntarist" type libertarianism because adherents to that view describe plunder as flowing from so-called "involuntary" transactions. They don't view capital's share of the national income as plunder like socialists do (even though it is unearned in the sense that it is not labored for). And they endorse the idea that distributive entitlement flows purely from the fact that you obtained whatever you have through so-called "voluntary" means. So from there, it's easy enough to say that, at least in theory, where wealth is gotten through "involuntary" acts (such as those involved in slavery), then you should right that wrong by transferring the wealth from the plunderer to the plundered. Once that is done, then the injustice created by the deviation from voluntarism is seen as cured, and laissez-faire anarcho-capitalist governance can continue on. Moot for Sanders Although this is a fun philosophical discussion, it is actually somewhat moot when it comes to Sanders. But this is precisely because he's not really a hardline socialist. He should come out for reparations. Nothing about his own political philosophy commitments, which tend to be of the liberal social democratic variety, should make reparations a complicated issue for him. But my point here is that, contrary to Coates' suggestion, Sanders is well-situated to seamlessly come out for reparations because he's not terribly radical. Reparations fits most cleanly within broadly liberal (and capitalist) conceptions of private ownership and broadly liberal (and capitalist) notions that distributive entitlement flows from some mix of "voluntary" transactions and personal productivity. Those who profess radical leftist critiques of these economic ideas actually tend to have the hardest time fitting reparations into their overall economic scheme. Put bluntly: you can't collectivize all the wealth and reparate it out privately at the same time. Ultimately, even those with hardline socialist views don't have much of a practical reason to oppose reparations in the near term, even if is philosophically at odds with their ideal socialist system. Surely a more egalitarian distribution of wealth (in the Rawlsian "property-owning democracy" vein) is a grade better than what we have now even if it is not snap socialization. And reparations works towards that end while also possibly salving a historical crime whose economic and noneconomic effects are still painfully with us.

In short, wealth is a stock that builds up over time and is passed down generations. Even if you could snap your fingers and make everything non-racist going forward, you'd still have wealth disparities owing to prior injustices. With that said, I think Coates is a bit muddled when it comes to the political valence of reparations. Although it seems to be sociologically true that reparations has the most purchase among rank-and-file people with left-wing economic views, philosophically speaking, it is much more of a liberal project. Socialism's Confusing Relationship With Reparations There are three basic issues with incorporating reparations into a truly hardline socialist view. First, hardline socialists believe that the plunder of working people is ongoing. Every year, around 30% of what's produced by workers in this country is paid out to owners of capital who did not work for it. The share of the national income going to capital is described by socialists as having been coercively extracted from workers through property relations created and enforced by the government. These days, few socialists would say that the plight of the worker is anywhere near as brutal as the plight of slaves. But on a strict reparations-for-plundered-wealth type rationale, they would be committed to believing that most working people in this country are being plundered right now and have been for centuries. If you run back the tape for all capital income, you'd find that the reparations owed to non-slave workers likely even exceeds those owed to slaves (again under a socialist-type framework). Second, hardline socialists do not generally believe that distributive entitlement is based on productivity. This poses a slight technical problem as reparation amounts are generally calculated accoding to estimates of slave productivity, with the implicit assumption being that people are owed what they produce. I say this is a slight technical problem because it mainly pertains to the calculation of reparations. The problem can be easily avoided by understanding reparations as compensation for an enormous crime rather than compensation for labor. This crime-based theory of reparations is how most reparations have worked, including reparations for victims of Japanese internment. Third, hardline socialists generally believe that basically all wealth should be owned collectively (certainly big assets that make up the bulk of the national wealth). Reparations generally envisions a transfer of private white wealth to private black wealth. But, hardline socialists don't really believe there should be any private wealth. To be sure, moving private wealth into a collective pot would be a huge net swing (in a sense) to those who currently lack much wealth (including Blacks). But it seems that, for some at least, moves that "disproportionately benefit" Blacks don't count as true reparations. There has to be something above and beyond that. Libertarian-ish Idea Philosophically speaking, reparations of the type normally discussed tends to sit the best with libertarian-type reasoning. Indeed, libertarian Robert Nozick famously endorsed reparations in his opus Anarchy, State, Utopia. Reparations finds a more natural home in "voluntarist" type libertarianism because adherents to that view describe plunder as flowing from so-called "involuntary" transactions. They don't view capital's share of the national income as plunder like socialists do (even though it is unearned in the sense that it is not labored for). And they endorse the idea that distributive entitlement flows purely from the fact that you obtained whatever you have through so-called "voluntary" means. So from there, it's easy enough to say that, at least in theory, where wealth is gotten through "involuntary" acts (such as those involved in slavery), then you should right that wrong by transferring the wealth from the plunderer to the plundered. Once that is done, then the injustice created by the deviation from voluntarism is seen as cured, and laissez-faire anarcho-capitalist governance can continue on. Moot for Sanders Although this is a fun philosophical discussion, it is actually somewhat moot when it comes to Sanders. But this is precisely because he's not really a hardline socialist. He should come out for reparations. Nothing about his own political philosophy commitments, which tend to be of the liberal social democratic variety, should make reparations a complicated issue for him. But my point here is that, contrary to Coates' suggestion, Sanders is well-situated to seamlessly come out for reparations because he's not terribly radical. Reparations fits most cleanly within broadly liberal (and capitalist) conceptions of private ownership and broadly liberal (and capitalist) notions that distributive entitlement flows from some mix of "voluntary" transactions and personal productivity. Those who profess radical leftist critiques of these economic ideas actually tend to have the hardest time fitting reparations into their overall economic scheme. Put bluntly: you can't collectivize all the wealth and reparate it out privately at the same time. Ultimately, even those with hardline socialist views don't have much of a practical reason to oppose reparations in the near term, even if is philosophically at odds with their ideal socialist system. Surely a more egalitarian distribution of wealth (in the Rawlsian "property-owning democracy" vein) is a grade better than what we have now even if it is not snap socialization. And reparations works towards that end while also possibly salving a historical crime whose economic and noneconomic effects are still painfully with us.

Published on January 28, 2016 00:00

January 27, 2016

My heartbreaking journey to Gitmo: A widow, a military prison & the enigma of human compassion