Helen H. Moore's Blog, page 877

January 31, 2016

Witnessing the Iowa caucus madness: Trump fanatics, protesters, candidate rallies and media onslaught turn heartland into outrageous political spectacle

I’m a server, not your sex toy: Some advice to the next dude who wants to comment on my looks

Recently, a young man walked into the bar where I was working, sat down, and told me that I was pretty. It just flew out of his mouth by accident; he’d obviously had a few. His vibe wasn’t slimy or aggressive. He just seemed excited to discover that a woman he found attractive would be opening his next beer. Convention suggests that the most normal and appropriate response from me would be a display of gratitude, but I wasn’t thankful. I just felt instantly beleaguered in a very familiar way.

I blankly responded that his thoughts on my appearance were not interesting to me and asked him what he’d like to drink. He stood there, drunk and caught off guard by his own boldness as well as my reaction. He tried to focus, knowing that the next move was his, his face reflecting the hazy fear that any dude who is at least trying to come correct feels when facing one of modern courtship’s classic gambles: I really do not want to be "that guy" versus this might just be crazy enough to work. He chose to hedge both ways and began slowly trying to dig himself out, struggling to enunciate and choose his words carefully but choosing the wrong ones. He bumbled between a handful of partially formed apologies before announcing that he felt awful, because I was clearly annoyed and he “would hate to offend such a pretty girl.”

I was so flattered that I instantly got super wet. Just joking! I was disgusted. It was 1 a.m. and I was tired. I wasn’t feeling combative enough to tell him to get lost immediately, especially knowing that he wouldn’t necessarily see the straight line between his actions and the punishment. But I also wasn’t in the mood to rah-rah a drunken stranger toward a potential enlightenment. Attempting diplomacy, I gave him a beer and put him in time out, instructing him to take 10 minutes to think about why even just his final statement was offensive. He wandered to the end of the bar and sat there in a fog.

After a little time had passed, I noticed his posture straighten and I turned to face him. His expression was solemn as I walked toward him, expecting at the very least an unconvincing performance of contrition. Instead, he stood up, took out his wallet, and tried to give me $10—not for drinks but because “sometimes you just have to pay for things.” Yes, this person had spent his time-out arriving at the conclusion that 10 whole dollars was enough to compensate me for feeling exposed, trapped, degraded and simultaneously invisible and on display at my own dumb job. I felt like a human sigh. “Just leave, please,” I said, and then he left.

As I step back and consider the way this story ended, my own generosity embarrasses me. I’m certainly not always that kind. But maybe I’m framing what I’m about to tell you with that particular anecdote to prove that I’m generally down to let a well-meaning dude off the hook if he acts right. When I was younger, I would sometimes even rescue these kinds of men from their own lingering discomfort by being sweet, because women are trained to reward men for all sorts of things by being sweet. I don’t do that anymore, because I’ve realized that smoothing it over with a stranger who has made me feel degraded usually feels more degrading than the actual offense and placating men in this way is a waste of my time. I should have known better than to even try with this dude, because I have already wasted so much of my time in parallel situations; every woman you know has wasted so much of her time.

I totally understand that it’s difficult to know when it is an appropriate time to give women sexual attention. The modern woman is baffling. We are on Tinder and we ball whoever we want and nobody is really allowed to judge anymore and we are feminists and we are easily angered by perceived degradation and we have a lot of feelings about words like "consent," which make your dick scared and we also might want you to pull our hair when we fuck. I imagine it feels impossible to know how and when to express your interest without offending women. It is a minefield, the stakes are high and nobody is safe.

Telling a woman that you think she is beautiful can seem very innocuous; sometimes it is. Sometimes, it will make her day. All this depends on context and I cannot explain when it is and is not OK, because that is like trying to explain intuition. Intuition about what will and won’t offend women is really just a set of odds, based on your lizard brain tabulating and comparing the outcomes of many similar previous interactions. But it’s important to recognize that these odds are skewed because women so often swallow their discomfort or indignation in order to keep the peace—especially if they are at work. Obviously all women have different boundaries and I’m not trying to slide into some essentialized decree about what women do and don’t want, but I think that a lot of mutual discomfort could be avoided if dudes would generally try to figure out whether a woman is interested before trying to figure out how to fuck her.

Although these situations are too nuanced and contextual to come down to do’s and don’ts, there are certain things to consider before giving sexual attention to a female bartender or server. Consider the power dynamic: Women will make more money if their patrons like them; often, their managers will scold them if they react negatively to what we have collectively deemed to be acceptable attention. Where does that leave the woman? She is expected to smile and say thank you, even if she feels mildly affronted, even if she finds you disgusting—although you would likely never detect this as she is forced to suspend these opinions at work.

Imagine you have a boss who repulses you, and one day, in front of a group of your peers, he presents you with a gift. It isn’t your birthday, but you have been singled out. “Open it,” he implores, beaming. “It’s just for you. You are going to love it.” You open it slowly, as everyone watches. You know that you are going to hate it, because you hate your boss, and you can feel yourself shrinking as you prepare to degrade yourself by pantomiming gratitude. You remove the final layer of tissue, and underneath it is a porkpie hat. A porkpie hat, made of leather. “Yay,” you say. “I totally love this.” You go home and drink a lot. You know you don’t deserve it, but you kind of hate yourself.

Across professional and personal contexts, women are beginning to articulate why we often feel dehumanized by the kind of sexual attention that might have seemed benign 10 years ago; we’re getting better at creating boundaries that work for us. But as we’ve become increasingly vocal about how things actually make us feel, the whole scene has become rightfully terrifying for the people trying to bag us. Dudes who are trying to respect and maybe fuck us are now in a double bind in which these two agendas seem very difficult but necessary to merge. The inverse of this, as I’ve experienced it, at least, is equally paradoxical: How am I supposed to reconcile wanting men to be attracted to me with not wanting to be objectified?

When I was younger, I couldn’t understand how to make this equation work. In my early 20s, I pretty much wanted all guys who weren’t my relatives or Nazis to want to fuck me, because that was the same as wanting them to like me. Playing into that dynamic generally felt like garbage, although I didn’t realize it at the time. I just knew I couldn’t figure out how to get what I wanted and feel respected.

Consider the way that this whole setup warps young women: Many women learn that they are most useful as bodies and that their bodies are most useful for sex before they even hit puberty. Most women I know learned that their sex parts were different than the rest of their bodies because boys or men put their hands or eyes or words all over those parts of us before fuck meant anything but a bad word.

I’ve always been tough, but it has taken me a long time to realize how much of that toughness grew on me as a coping mechanism; how much of that toughness is damage. Men have fucked with my dignity since I was a child, but the things that have happened to me have happened to all of us. When the bad things that happen are normal, you become tough. It’s devastating how tough I am.

So, as a 30-year-old woman who has been through a range of horribly exploitative sexual and emotional experiences—you know, just like pretty much every woman you know—I really don’t want to know anymore if a stranger finds me attractive. Not right out of the gate. Hell no. There are so many more interesting things about me than my body. Do you even care about them? This is why I cherish my friendships with straight dudes who would never try to fuck me even if we are trashed, and is probably part of why I hang out with a lot of queer people.

This is why I’ve gone home in tears after someone I respect says they think I’m smart and funny and interesting and they’d like to have a drink and rap about the world, and then just tries to fuck me after I patiently dodge their advances all night. Were they not even paying attention? Did they even want to rap about the world with me? I am still, as a grown woman, trying not to mentally respond to that situation by thinking: “Well, that person just wanted to fuck you. Maybe you are not really that smart or interesting.” That precise feeling is one that I don’t really think straight dudes can fully relate to: You are invisible, but they still want to fuck you. They do not see you or hear you. They still might rape you. This is why somebody putting their eyes all over me or immediately telling me they like the way I look is no longer flattering. Because it makes me feel fucking invisible.

I know this is confusing. Assholes have wrecked the whole concept of spitting game, and there is no longer a blueprint for how to hit on women. As far as expressing your interest in a woman while she’s working, I’m not saying it’s impossible to do this respectfully, but consider the stakes before you impose your desire on another human being. Receiving sexual attention from a stranger just affirms that everyone is clocking us every moment and deciding how much we matter based on whether or not they like what they see. If you’re going to holler at somebody while they’re working, try to gauge her interest in your interest before you put it on her. If you’re working really hard to make her see how great you are, she is probably working even harder to escape the conversation without hurting your feelings. If she seems to be down, try building rapport in the same way that you would with anyone you don’t care about seeing naked. Talk about things you like to talk about and ask her what she thinks. Perhaps mention a thing you are doing in the coming days and leave room for her to invite herself. My favorite male bar patron stealth game is someone saying “I’m thinking about leaving soon,” and then trailing off with casual implication.

As a baseline, in any context, treat women like people you are not engaging with primarily because you might get to put your dick inside of them. When you are out in the world--at a bar, at a show, making time with a lady--and you realize you’d like to get down with her, put your game on pause and feel out her vibe. It is very likely that this woman can detect your interest. Try laying back. The process of you getting laid should not feel like you are angling for victory in a war of attrition. You getting laid should not require lengthy negotiations, disingenuous angles, or both of you getting blotto enough to just cave already. If you’re feeling her, look at her like an individual with a mind and a voice, and then, guess what? You might see parts of her you never would have seen otherwise, and she will be happy that you took the time to see her, and then maybe you guys will be so happy to see each other that you fuck each other's brains out.

Recently, a young man walked into the bar where I was working, sat down, and told me that I was pretty. It just flew out of his mouth by accident; he’d obviously had a few. His vibe wasn’t slimy or aggressive. He just seemed excited to discover that a woman he found attractive would be opening his next beer. Convention suggests that the most normal and appropriate response from me would be a display of gratitude, but I wasn’t thankful. I just felt instantly beleaguered in a very familiar way.

I blankly responded that his thoughts on my appearance were not interesting to me and asked him what he’d like to drink. He stood there, drunk and caught off guard by his own boldness as well as my reaction. He tried to focus, knowing that the next move was his, his face reflecting the hazy fear that any dude who is at least trying to come correct feels when facing one of modern courtship’s classic gambles: I really do not want to be "that guy" versus this might just be crazy enough to work. He chose to hedge both ways and began slowly trying to dig himself out, struggling to enunciate and choose his words carefully but choosing the wrong ones. He bumbled between a handful of partially formed apologies before announcing that he felt awful, because I was clearly annoyed and he “would hate to offend such a pretty girl.”

I was so flattered that I instantly got super wet. Just joking! I was disgusted. It was 1 a.m. and I was tired. I wasn’t feeling combative enough to tell him to get lost immediately, especially knowing that he wouldn’t necessarily see the straight line between his actions and the punishment. But I also wasn’t in the mood to rah-rah a drunken stranger toward a potential enlightenment. Attempting diplomacy, I gave him a beer and put him in time out, instructing him to take 10 minutes to think about why even just his final statement was offensive. He wandered to the end of the bar and sat there in a fog.

After a little time had passed, I noticed his posture straighten and I turned to face him. His expression was solemn as I walked toward him, expecting at the very least an unconvincing performance of contrition. Instead, he stood up, took out his wallet, and tried to give me $10—not for drinks but because “sometimes you just have to pay for things.” Yes, this person had spent his time-out arriving at the conclusion that 10 whole dollars was enough to compensate me for feeling exposed, trapped, degraded and simultaneously invisible and on display at my own dumb job. I felt like a human sigh. “Just leave, please,” I said, and then he left.

As I step back and consider the way this story ended, my own generosity embarrasses me. I’m certainly not always that kind. But maybe I’m framing what I’m about to tell you with that particular anecdote to prove that I’m generally down to let a well-meaning dude off the hook if he acts right. When I was younger, I would sometimes even rescue these kinds of men from their own lingering discomfort by being sweet, because women are trained to reward men for all sorts of things by being sweet. I don’t do that anymore, because I’ve realized that smoothing it over with a stranger who has made me feel degraded usually feels more degrading than the actual offense and placating men in this way is a waste of my time. I should have known better than to even try with this dude, because I have already wasted so much of my time in parallel situations; every woman you know has wasted so much of her time.

I totally understand that it’s difficult to know when it is an appropriate time to give women sexual attention. The modern woman is baffling. We are on Tinder and we ball whoever we want and nobody is really allowed to judge anymore and we are feminists and we are easily angered by perceived degradation and we have a lot of feelings about words like "consent," which make your dick scared and we also might want you to pull our hair when we fuck. I imagine it feels impossible to know how and when to express your interest without offending women. It is a minefield, the stakes are high and nobody is safe.

Telling a woman that you think she is beautiful can seem very innocuous; sometimes it is. Sometimes, it will make her day. All this depends on context and I cannot explain when it is and is not OK, because that is like trying to explain intuition. Intuition about what will and won’t offend women is really just a set of odds, based on your lizard brain tabulating and comparing the outcomes of many similar previous interactions. But it’s important to recognize that these odds are skewed because women so often swallow their discomfort or indignation in order to keep the peace—especially if they are at work. Obviously all women have different boundaries and I’m not trying to slide into some essentialized decree about what women do and don’t want, but I think that a lot of mutual discomfort could be avoided if dudes would generally try to figure out whether a woman is interested before trying to figure out how to fuck her.

Although these situations are too nuanced and contextual to come down to do’s and don’ts, there are certain things to consider before giving sexual attention to a female bartender or server. Consider the power dynamic: Women will make more money if their patrons like them; often, their managers will scold them if they react negatively to what we have collectively deemed to be acceptable attention. Where does that leave the woman? She is expected to smile and say thank you, even if she feels mildly affronted, even if she finds you disgusting—although you would likely never detect this as she is forced to suspend these opinions at work.

Imagine you have a boss who repulses you, and one day, in front of a group of your peers, he presents you with a gift. It isn’t your birthday, but you have been singled out. “Open it,” he implores, beaming. “It’s just for you. You are going to love it.” You open it slowly, as everyone watches. You know that you are going to hate it, because you hate your boss, and you can feel yourself shrinking as you prepare to degrade yourself by pantomiming gratitude. You remove the final layer of tissue, and underneath it is a porkpie hat. A porkpie hat, made of leather. “Yay,” you say. “I totally love this.” You go home and drink a lot. You know you don’t deserve it, but you kind of hate yourself.

Across professional and personal contexts, women are beginning to articulate why we often feel dehumanized by the kind of sexual attention that might have seemed benign 10 years ago; we’re getting better at creating boundaries that work for us. But as we’ve become increasingly vocal about how things actually make us feel, the whole scene has become rightfully terrifying for the people trying to bag us. Dudes who are trying to respect and maybe fuck us are now in a double bind in which these two agendas seem very difficult but necessary to merge. The inverse of this, as I’ve experienced it, at least, is equally paradoxical: How am I supposed to reconcile wanting men to be attracted to me with not wanting to be objectified?

When I was younger, I couldn’t understand how to make this equation work. In my early 20s, I pretty much wanted all guys who weren’t my relatives or Nazis to want to fuck me, because that was the same as wanting them to like me. Playing into that dynamic generally felt like garbage, although I didn’t realize it at the time. I just knew I couldn’t figure out how to get what I wanted and feel respected.

Consider the way that this whole setup warps young women: Many women learn that they are most useful as bodies and that their bodies are most useful for sex before they even hit puberty. Most women I know learned that their sex parts were different than the rest of their bodies because boys or men put their hands or eyes or words all over those parts of us before fuck meant anything but a bad word.

I’ve always been tough, but it has taken me a long time to realize how much of that toughness grew on me as a coping mechanism; how much of that toughness is damage. Men have fucked with my dignity since I was a child, but the things that have happened to me have happened to all of us. When the bad things that happen are normal, you become tough. It’s devastating how tough I am.

So, as a 30-year-old woman who has been through a range of horribly exploitative sexual and emotional experiences—you know, just like pretty much every woman you know—I really don’t want to know anymore if a stranger finds me attractive. Not right out of the gate. Hell no. There are so many more interesting things about me than my body. Do you even care about them? This is why I cherish my friendships with straight dudes who would never try to fuck me even if we are trashed, and is probably part of why I hang out with a lot of queer people.

This is why I’ve gone home in tears after someone I respect says they think I’m smart and funny and interesting and they’d like to have a drink and rap about the world, and then just tries to fuck me after I patiently dodge their advances all night. Were they not even paying attention? Did they even want to rap about the world with me? I am still, as a grown woman, trying not to mentally respond to that situation by thinking: “Well, that person just wanted to fuck you. Maybe you are not really that smart or interesting.” That precise feeling is one that I don’t really think straight dudes can fully relate to: You are invisible, but they still want to fuck you. They do not see you or hear you. They still might rape you. This is why somebody putting their eyes all over me or immediately telling me they like the way I look is no longer flattering. Because it makes me feel fucking invisible.

I know this is confusing. Assholes have wrecked the whole concept of spitting game, and there is no longer a blueprint for how to hit on women. As far as expressing your interest in a woman while she’s working, I’m not saying it’s impossible to do this respectfully, but consider the stakes before you impose your desire on another human being. Receiving sexual attention from a stranger just affirms that everyone is clocking us every moment and deciding how much we matter based on whether or not they like what they see. If you’re going to holler at somebody while they’re working, try to gauge her interest in your interest before you put it on her. If you’re working really hard to make her see how great you are, she is probably working even harder to escape the conversation without hurting your feelings. If she seems to be down, try building rapport in the same way that you would with anyone you don’t care about seeing naked. Talk about things you like to talk about and ask her what she thinks. Perhaps mention a thing you are doing in the coming days and leave room for her to invite herself. My favorite male bar patron stealth game is someone saying “I’m thinking about leaving soon,” and then trailing off with casual implication.

As a baseline, in any context, treat women like people you are not engaging with primarily because you might get to put your dick inside of them. When you are out in the world--at a bar, at a show, making time with a lady--and you realize you’d like to get down with her, put your game on pause and feel out her vibe. It is very likely that this woman can detect your interest. Try laying back. The process of you getting laid should not feel like you are angling for victory in a war of attrition. You getting laid should not require lengthy negotiations, disingenuous angles, or both of you getting blotto enough to just cave already. If you’re feeling her, look at her like an individual with a mind and a voice, and then, guess what? You might see parts of her you never would have seen otherwise, and she will be happy that you took the time to see her, and then maybe you guys will be so happy to see each other that you fuck each other's brains out.

“The point of having f**k-you money”: We’ve seen how the economy broke down in ’08 — Showtime’s “Billions” shows us why

“It’s not a guilty pleasure”: “American Crime Story” faces the complexities of the O.J. trial head-on

The time Dave Stewart got a new soul: “I’d had this near-death experience … and I came out of it a completely different person”

Why Iowa matters: A Donald Trump victory in Monday’s caucus would make him virtually unstoppable

How to defeat the Koch brothers: Here’s what it could take to end their right-wing stranglehold

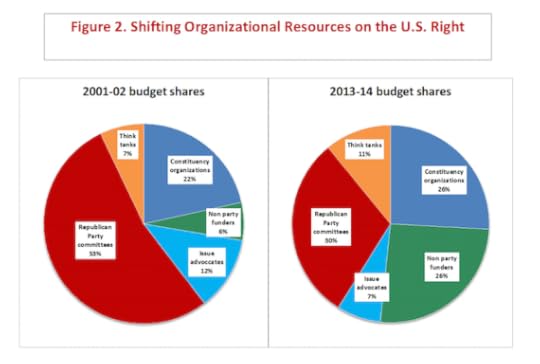

Koch and his brother David Koch have quietly assembled, piece by piece, a privatized political and policy advocacy operation like no other in American history that today includes hundreds of donors and employs 1,200 full-time, year-round staffers in 107 offices nationwide. That’s about 3½ times as many employees as the Republican National Committee and its congressional campaign arms had on their main payrolls last month, according to POLITICO’s analysis of tax and campaign documents and interviews with sources familiar with the network.At the same time as the Koch brothers have expanded into electoral politics, traditional party organizations have become weaker. Political scientists Theda Skocpol and Alex Hertel-Fernandez, who have studied organizations on the left and right extensively, find funding non-party organizations have increased dramatically on the right while the Republican Party has become weaker (see chart).

Hertel-Fernandez tells me,

Hertel-Fernandez tells me, “Political resources are now far less likely to flow through the official Republican committees than they were a decade ago. Instead, contributions are increasingly likely to go through outside groups. By far, the most prominent of these extra party funders is the array of groups directed by the Koch brothers.”Their research aligns with extensive work by journalists. In his 2014 book, "Big Money," Kenneth Vogel writes of the Koch network,

“Intentionally or not, this new system has eroded the power of the official parties that have rigidly controlled modern politics for decades… The result is the privatization of a system that we’d always thought of as public-a hi-jacking of American politics by the ultra-rich.”Dan Balz notes that,

“When W. Clement Stone, an insurance magnate and philanthropist, gave $2 million to Richard M. Nixon’s 1972 campaign, it caused public outrage and contributed to a movement that produced the post-Watergate reforms in campaign financing. Accounting for inflation, that $2 million would equal about $11 million in today’s dollars.”In 2015, the Koch brothers revealed a spending goal of $889 million for their network, nearly 81 times more than Stone, and far more than the $657 million that the Republican Party spent in 2012. In her book "Dark Money," Jane Mayer argues that this has long been a goal for some on the right, writing that Karl Rove “had long dreamed of creating a conservative political machine outside the traditional parties’ control that could be funded by virtually unlimited private fortunes.” But Rove’s goal may soon become a nightmare. While most people have focused on the part of the GOP's post-election autopsy that worried about its overwhelmingly white base, a more important nugget may well be its discussion of the increasing power of donors. The document reads,

“The current campaign finance environment has led to a handful of friends and allied groups dominating our side’s efforts. This is not healthy. A lot of centralized authority in the hand of a few people at these outside organizations is dangerous for our party.”Take the Medicaid expansion, which has been stunted by powerful political interests, despite rather strong public support. Hertel-Fernandez, Theda Skocpol and Daniel Lynch find that while GOP governors and business groups were favorable to the Medicaid expansion, Koch-backed groups like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and AFP (Americans for Prosperity) fought vigorously against it (I’ve discussed this work here). As the Koch brothers grow stronger, there will be more fights between the GOP and this increasingly powerful and unaccountable family. Meanwhile, Ken Vogel reports that in 2014, the Chamber of Commerce “considered wading into the 2014 Republican primary in a major way.” Their goal: “ousting tea party conservatives and replacing them with more business-friendly pragmatists.” Vogel cites Club for Growth president Chris Chocola who criticizes former Gov. Haley Barbour because,

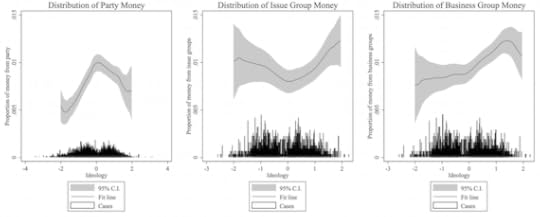

“Haley wants every Republican to win, regardless of how they vote for office. The Club for Growth PAC helps elect candidates who support limited government and free markets. Unfortunately, the two goals coincide less often than the Republican Establishment cares to admit.” [emphasis mine]Quotes like this indicate that there will be increasingly fraught relationships between outside groups and the GOP establishment. Could the solution be stronger parties? What, then, can be done? In their book, "Campaign Finance and Political Polarization," political scientists Brian Schaffner and Ray La Raja use a vast amount of state-level data to argue that stronger parties lead to less ideological candidates. As the chart below from their book shows, the distribution of party money favors more moderate candidates, while issue groups like the Koch network favor more extreme candidates, and business groups favor the right. It’s also worth noting that these data suggest an asymmetry in the parties, with Republicans more likely to support candidates further to the extreme than Democrats (thus the rightward tilt of the “party money” graph). Their extensive analysis of state-level data, over a long historical period, suggests, “In states where parties face more restrictive campaign finance laws, legislators are further from the center than in states where parties are financially unconstrained.”

Although La Raja and Schaffner focus on polarization, a recent report by Daniel Weiner and Ian Vandewalker of the Brennan Center for Justice makes a different argument: Stronger parties could actually strengthen democracy. They write,

Although La Raja and Schaffner focus on polarization, a recent report by Daniel Weiner and Ian Vandewalker of the Brennan Center for Justice makes a different argument: Stronger parties could actually strengthen democracy. They write, “Targeted measures to strengthen political parties, including public financing and a relaxing of certain campaign finance regulations, could help produce a more inclusive and transparent politics.”Their core argument is that parties are accountable to voters, while donors are not. They compare two of the biggest spenders in 2014: the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC), a party organization, and the Senate Majority PAC, a super PAC. They note that,

“the Senate Majority PAC. The DSCC took in 44 percent of its contributions from small donors of $200 or less, while Senate Majority PAC received less than one tenth of one percent of its funds from small donors.”Further,

“Of the $46 million that Senate Majority PAC spent in total, $36 million came from just 23 donors who each gave half a million dollars or more, according to FEC data.”They also note that parties are more transparent than PACs, so stronger parties would bring more sunlight to the democratic process. Though they approach the argument from different angles, the Brennan Center Report and the La Raja/Schaffner book share in common the proposal that public financing should be available to parties and that limits on party contributions to candidates should be reduced or eliminated. Brian explained his thinking to me thusly:

“While the Mitch McConnells and John Boehners of the world are certainly not moderates, they are not nearly as polarized or uncompromising as super PAC funders like the the Kochs and Adelson. And it's the fear of backlash from those outside forces which is working against any kind of compromise in Washington."He adds, "The Koch network now has many of the aspects of a political party -- GOTV, complex data analytics, candidate selection -- without the accountability to voters." Political scientist Seth Masket notes that the proposal to strengthen parties had quite a bit of support at a Brookings event he attended. He argues for a system in which parties can funnel public money to preferred campaigns. However, political scientist Lee Drutman is highly skeptical, at least of the idea that unlimited funding would decrease polarization. He argues that there are t0o few competitive districts and little incentive from parties to run moderates if there were. He also notes, correctly, that it’s unlikely small donors would increase political polarization. Conclusion Because the current composition of the Supreme Court makes reform difficult, progressives have good reasons to be supportive of proposals to strengthen parties, but also good reasons to be wary. The reason to support such a campaign is, somewhat ironically, that as the Republican Party has become weaker, even more right-wing forces have become stronger. The rise of extreme candidates like Trump can certainly be explained in part by the weakness of the GOP compared to outside donors. The negative side is that the Democratic Party has never been particularly kind to economic progressivism, and that big money is inherently anti-democratic, whichever channel it flows through. On the issue of public financing, there is mutual agreement: La Raja tells me, “I think reformers should be focused more on how the money is raised than on how it is spent. That is why some form of public financing makes sense.” He argues that campaigns should be seen as a public good (because they raise awareness, knowledge and mobilization) and therefore supported by public funds. Empowering small donors means empowering average Americans and bolstering independent political power for progressives and people of color, who currently make up a vanishing share of the donor class. Even more fundamentally, it’s obvious that tackling economic inequality is essential to tackling political inequality. As Louis Brandeis writes (in a quote Jane Mayer uses for the epigraph of her book), “We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we may have wealth concentrated in the hands of the few, but we can’t have both.”

Our terrified hyperpatriots: Here’s what Palin, Trump and anti-Muslim extremists fear most

January 30, 2016

The porn industry is a lot less lucrative than you might think

Being a porn star isn’t as easy as it sounds. Sure, most of us can point to a few big names who have made it mainstream, but working in the industry isn't quite as lucrative as movies like Boogie Nights would have you think. In fact, performer pay rates are now at an all-time low. Increasingly, stars are starting to rely on alternative streams of revenue like product endorsement deals, snapchat requests, camming platforms and escorting to get by. According to a recent report by CNBC, the average male porn actor earns around $500-$600 per scene. More established stars get around $700-$900. "Superstars” can expect wages around $1,500. Some say gay scenes pay better. Popular performers can make upward of $5,000 for a shoot, which might help explain the “gay-for-pay” phenomenon. It's one of the few industries where women generally start out at a higher rate. Steven Hirsh, owner of the hugely profitable Vivid Studios, told CNBC, “When the girls first get into the business and they’re new, I think they can command additional money for different sex acts." “Initially they make more money, then it depends on how popular they become,” he added. According to the report, the average actress gets paid somewhere between $800 and $1,000 for “traditional” sex scenes (aka between a man and woman). Big-name actresses can reel in around $1,500, sometimes $2,000. Newcomers with a “bad reputation,” however, might earn as little as $300. Those looking for higher wages are often encouraged to participate in more trying scenes. According to the report, the “most extreme” stunts can go for $1,800 to $2,500 (double anal, anyone?). For those with a large enough fan base, feature dancing might be the way to go. One actress/dancer told CNBC that she regularly earns $7,000 to $10,000 per appearance, which can last two days. Then there’s the behind-the-scenes staff, which includes the directors, camerapeople, sound technicians, producers, writers, photographers, makeup artists and all the other people it takes to put a scene together. Out of this group, the directors come out on top. In general, a director of a porn film will earn $1,000-$1,500 per day. In the event they are “required to do dramatically more than direct,” that rate can jump as high as $3,000, though CBNC notes that few studios are actually willing to pay that amount. Writers earn considerably less. Their paycheck falls in the ballpark of $250-$400 per day, and most shoots only last a day or two. Tentpole porn films can take just four to eight hours. Camerapeople generally make around $500-$700 (those with their own cameras are more likely to fall on the higher end of that scale), Sound technicians earn $300-$400 while production assistants can expect to take home $100 to $250 per day. Makeup artists do fairly well, earning around $500 for working a full day on set. Those who don’t feel like hanging around all day can charge between $100 and $150 per person. The report reads, “Ultimately, assuming they have a decent agent, a performer’s salary comes down to three things—two of which are in their control: Their work ethic and frequency, their entrepreneurial spirit and their popularity.” There is, however, another factor to consider: their longevity. The report adds: “Porn is an industry that regularly chews up and spits out performers. Many quit after just one scene or after a few months. Some stick around for a few years, but then disappear. But a select few have chosen to make this a true career — and as in the mainstream world, those are the ones who tend to pocket the most.”

Being a porn star isn’t as easy as it sounds. Sure, most of us can point to a few big names who have made it mainstream, but working in the industry isn't quite as lucrative as movies like Boogie Nights would have you think. In fact, performer pay rates are now at an all-time low. Increasingly, stars are starting to rely on alternative streams of revenue like product endorsement deals, snapchat requests, camming platforms and escorting to get by. According to a recent report by CNBC, the average male porn actor earns around $500-$600 per scene. More established stars get around $700-$900. "Superstars” can expect wages around $1,500. Some say gay scenes pay better. Popular performers can make upward of $5,000 for a shoot, which might help explain the “gay-for-pay” phenomenon. It's one of the few industries where women generally start out at a higher rate. Steven Hirsh, owner of the hugely profitable Vivid Studios, told CNBC, “When the girls first get into the business and they’re new, I think they can command additional money for different sex acts." “Initially they make more money, then it depends on how popular they become,” he added. According to the report, the average actress gets paid somewhere between $800 and $1,000 for “traditional” sex scenes (aka between a man and woman). Big-name actresses can reel in around $1,500, sometimes $2,000. Newcomers with a “bad reputation,” however, might earn as little as $300. Those looking for higher wages are often encouraged to participate in more trying scenes. According to the report, the “most extreme” stunts can go for $1,800 to $2,500 (double anal, anyone?). For those with a large enough fan base, feature dancing might be the way to go. One actress/dancer told CNBC that she regularly earns $7,000 to $10,000 per appearance, which can last two days. Then there’s the behind-the-scenes staff, which includes the directors, camerapeople, sound technicians, producers, writers, photographers, makeup artists and all the other people it takes to put a scene together. Out of this group, the directors come out on top. In general, a director of a porn film will earn $1,000-$1,500 per day. In the event they are “required to do dramatically more than direct,” that rate can jump as high as $3,000, though CBNC notes that few studios are actually willing to pay that amount. Writers earn considerably less. Their paycheck falls in the ballpark of $250-$400 per day, and most shoots only last a day or two. Tentpole porn films can take just four to eight hours. Camerapeople generally make around $500-$700 (those with their own cameras are more likely to fall on the higher end of that scale), Sound technicians earn $300-$400 while production assistants can expect to take home $100 to $250 per day. Makeup artists do fairly well, earning around $500 for working a full day on set. Those who don’t feel like hanging around all day can charge between $100 and $150 per person. The report reads, “Ultimately, assuming they have a decent agent, a performer’s salary comes down to three things—two of which are in their control: Their work ethic and frequency, their entrepreneurial spirit and their popularity.” There is, however, another factor to consider: their longevity. The report adds: “Porn is an industry that regularly chews up and spits out performers. Many quit after just one scene or after a few months. Some stick around for a few years, but then disappear. But a select few have chosen to make this a true career — and as in the mainstream world, those are the ones who tend to pocket the most.”

Being a porn star isn’t as easy as it sounds. Sure, most of us can point to a few big names who have made it mainstream, but working in the industry isn't quite as lucrative as movies like Boogie Nights would have you think. In fact, performer pay rates are now at an all-time low. Increasingly, stars are starting to rely on alternative streams of revenue like product endorsement deals, snapchat requests, camming platforms and escorting to get by. According to a recent report by CNBC, the average male porn actor earns around $500-$600 per scene. More established stars get around $700-$900. "Superstars” can expect wages around $1,500. Some say gay scenes pay better. Popular performers can make upward of $5,000 for a shoot, which might help explain the “gay-for-pay” phenomenon. It's one of the few industries where women generally start out at a higher rate. Steven Hirsh, owner of the hugely profitable Vivid Studios, told CNBC, “When the girls first get into the business and they’re new, I think they can command additional money for different sex acts." “Initially they make more money, then it depends on how popular they become,” he added. According to the report, the average actress gets paid somewhere between $800 and $1,000 for “traditional” sex scenes (aka between a man and woman). Big-name actresses can reel in around $1,500, sometimes $2,000. Newcomers with a “bad reputation,” however, might earn as little as $300. Those looking for higher wages are often encouraged to participate in more trying scenes. According to the report, the “most extreme” stunts can go for $1,800 to $2,500 (double anal, anyone?). For those with a large enough fan base, feature dancing might be the way to go. One actress/dancer told CNBC that she regularly earns $7,000 to $10,000 per appearance, which can last two days. Then there’s the behind-the-scenes staff, which includes the directors, camerapeople, sound technicians, producers, writers, photographers, makeup artists and all the other people it takes to put a scene together. Out of this group, the directors come out on top. In general, a director of a porn film will earn $1,000-$1,500 per day. In the event they are “required to do dramatically more than direct,” that rate can jump as high as $3,000, though CBNC notes that few studios are actually willing to pay that amount. Writers earn considerably less. Their paycheck falls in the ballpark of $250-$400 per day, and most shoots only last a day or two. Tentpole porn films can take just four to eight hours. Camerapeople generally make around $500-$700 (those with their own cameras are more likely to fall on the higher end of that scale), Sound technicians earn $300-$400 while production assistants can expect to take home $100 to $250 per day. Makeup artists do fairly well, earning around $500 for working a full day on set. Those who don’t feel like hanging around all day can charge between $100 and $150 per person. The report reads, “Ultimately, assuming they have a decent agent, a performer’s salary comes down to three things—two of which are in their control: Their work ethic and frequency, their entrepreneurial spirit and their popularity.” There is, however, another factor to consider: their longevity. The report adds: “Porn is an industry that regularly chews up and spits out performers. Many quit after just one scene or after a few months. Some stick around for a few years, but then disappear. But a select few have chosen to make this a true career — and as in the mainstream world, those are the ones who tend to pocket the most.”

Being a porn star isn’t as easy as it sounds. Sure, most of us can point to a few big names who have made it mainstream, but working in the industry isn't quite as lucrative as movies like Boogie Nights would have you think. In fact, performer pay rates are now at an all-time low. Increasingly, stars are starting to rely on alternative streams of revenue like product endorsement deals, snapchat requests, camming platforms and escorting to get by. According to a recent report by CNBC, the average male porn actor earns around $500-$600 per scene. More established stars get around $700-$900. "Superstars” can expect wages around $1,500. Some say gay scenes pay better. Popular performers can make upward of $5,000 for a shoot, which might help explain the “gay-for-pay” phenomenon. It's one of the few industries where women generally start out at a higher rate. Steven Hirsh, owner of the hugely profitable Vivid Studios, told CNBC, “When the girls first get into the business and they’re new, I think they can command additional money for different sex acts." “Initially they make more money, then it depends on how popular they become,” he added. According to the report, the average actress gets paid somewhere between $800 and $1,000 for “traditional” sex scenes (aka between a man and woman). Big-name actresses can reel in around $1,500, sometimes $2,000. Newcomers with a “bad reputation,” however, might earn as little as $300. Those looking for higher wages are often encouraged to participate in more trying scenes. According to the report, the “most extreme” stunts can go for $1,800 to $2,500 (double anal, anyone?). For those with a large enough fan base, feature dancing might be the way to go. One actress/dancer told CNBC that she regularly earns $7,000 to $10,000 per appearance, which can last two days. Then there’s the behind-the-scenes staff, which includes the directors, camerapeople, sound technicians, producers, writers, photographers, makeup artists and all the other people it takes to put a scene together. Out of this group, the directors come out on top. In general, a director of a porn film will earn $1,000-$1,500 per day. In the event they are “required to do dramatically more than direct,” that rate can jump as high as $3,000, though CBNC notes that few studios are actually willing to pay that amount. Writers earn considerably less. Their paycheck falls in the ballpark of $250-$400 per day, and most shoots only last a day or two. Tentpole porn films can take just four to eight hours. Camerapeople generally make around $500-$700 (those with their own cameras are more likely to fall on the higher end of that scale), Sound technicians earn $300-$400 while production assistants can expect to take home $100 to $250 per day. Makeup artists do fairly well, earning around $500 for working a full day on set. Those who don’t feel like hanging around all day can charge between $100 and $150 per person. The report reads, “Ultimately, assuming they have a decent agent, a performer’s salary comes down to three things—two of which are in their control: Their work ethic and frequency, their entrepreneurial spirit and their popularity.” There is, however, another factor to consider: their longevity. The report adds: “Porn is an industry that regularly chews up and spits out performers. Many quit after just one scene or after a few months. Some stick around for a few years, but then disappear. But a select few have chosen to make this a true career — and as in the mainstream world, those are the ones who tend to pocket the most.”

The radical left has Bernie Sanders all wrong