Shevlin Sebastian's Blog, page 96

January 30, 2016

India’s First Blade Runner

Major DP Singh lost his right leg as a result of the Kargil War. Today he is a runner as well as an inspirational speaker

Major DP Singh lost his right leg as a result of the Kargil War. Today he is a runner as well as an inspirational speakerBy Shevlin Sebastian

At the start of the Spice Cost Marathon in Kochi, in November, 2015, Uday Bagde, a participant from Ahmedabad, had a moment's hesitation. A member of an all-India group called The Challenging Ones, he turned to founder Major DP Singh and said, “Sir, is it necessary to wear shorts while running, instead of trackpants?”

Singh replied that runners can only wear shorts. So, Bagde took off his track pants and set out in his white shorts. Immediately he caught the eye, because he was wearing a prosthetic.

Later, when he completed his quota of five kilometres, he told Singh, “In this short span, I have changed as a person. Earlier, I was shy about showing my prosthetic in public. But during the run people told me, 'Oh my God, you are an inspiration for me.'”

Singh is also an inspiration. He is India's original blade runner, in the manner of South Africa's famed running champion Oscar Pistorius. “When I wear a blade, it gives me the same posture as a normal runner,” he says. “One part of the blade works as a toe. It gives a push, and helps me to move forward.”

Thus far, Singh has taken part in 18 half marathons (21 kms) in places like Mumbai, Delhi, Kochi, Chandigarh, Ladakh, and Sangla. Incidentally, these type of limbs are not manufactured in India. Singh has imported one, made of carbon fibre, at a cost of Rs 7 lakh.

The Delhi-based runner began running six years ago. “I wanted to do everything that a normal person can do,” says Singh. “The most difficult aspect for someone, without a leg, is to run, and to run long distance. Once I began running I felt an immense self-confidence.”

And there was a changed attitude among the people towards Singh. “There were no longer any looks of sympathy,” he says. “Instead, they quickly accepted me as a normal person. Running also releases endorphins in the brain. As a result, I feel good and happy. And in control.”

But Singh had experienced moments when things went haywire. On the morning of July 15, 1999, he was part of an Army team taking part in 'Operation Vijay' during the Kargil War between India and Pakistan. A bomb burst just five feet away from him at the Chicken Neck section in Akhnoor. By the time, he regained consciousness, the situation looked grim. Gangrene had set in. Despite the best treatment in several hospitals, the doctors had no option but to amputate his leg.

And his first thought was highly unusual. “I felt that now I will be able to see life from a disabled person's eyes, and do something about it,” says Singh. “Today, I believe that this is the path chosen by the Almighty himself, so I cannot question Him at all.”

Singh carries on in this vein: “My present life is much better. Had I not been injured, I would have been a mediocre person. But because of the amputation, I touched the nadir of my life. And from there I bounced back. It is the bouncing back that makes you a different person.”

It gave him the confidence to start an organisation for amputees called The Challenging Ones. “The name comes from being physically challenged,” says Singh. “We wanted to convert members, through sports, to become a challenger in life, and help them adopt a positive attitude.”

There are 800 members from all over India. For the Kochi race, Singh was able to persuade IDBI-Federal Life Insurance to provide air tickets and five-star hotel accommodation for 18 runners from all over the country. Out of them, 11 were coming out of their home city for the first time since their amputation. “It was an emotional moment for them,” says Singh. “I felt happy that I could do my bit for my fellow amputees.”

In his day-to-day life Singh is an inspirational speaker. He has talked about his life experiences at companies, school and colleges. “Now, you tell me, wasn't my amputation a good thing?” says Singh, with a smile.

Published on January 30, 2016 20:24

Many Firsts To Her Credit

Thanks to her many achievements, Nirmala Lilly has become the first Indian to be interviewed in the Toastmaster international magazine

Thanks to her many achievements, Nirmala Lilly has become the first Indian to be interviewed in the Toastmaster international magazinePhotos: Nirmala Lilly; the cover of the December Toastmaster magazine

By Shevlin Sebastian

One day, in September, 2015, Nirmala Lilly got an e-mail which took her by surprise. It was from Shannon Dewey, an editorial team member of the Toastmaster international magazine. (The Toasmasters is a world-wide institution which helps members to improve their speaking and leadership skills). "I am very interested in interviewing you for a 'Member Moment' profile, in an upcoming issuem," wrote Shannon.

Following Nirmala's assent, there was a regular exchange of mails for the next few weeks, as Nirmala had to answer several questions sent by the editorial team.

And, finally, in the December issue, the article appeared. Thus, the Kochi-based Nirmala created a bit of history: she is the first Indian Toastmaster to be interviewed in the magazine. "What really excited me was to see the small Indian flag that was placed next to my photo," she says. Incidentally, the magazine is available in 135 countries.

In the interview, Nirmala said, "Toastmasters was and is the medicine, as far as articulation is concerned. It gave me the courage to quit and get better jobs, better positions and better [salary] packages and, of course, recognition."

Like most good public speakers, Nirmala was painfully shy for several years. "I was petrified to stand in front of an audience," she says. "This affected my career in the earlier years."

Thanks to the encouragement given by CM Daniel and Paul Manjooran, the founders of the Toastmasters movement in Kerala, Nirmala attended a few meetings, but could not commit herself to join. The turning point came when a Toastmaster, by the name of George Mathai, said, "Nirmala, it is nice to have a honeymoon. But it is better to get married and have a honeymoon."

So, Nirmala joined in August, 2006. "Thereafter, I took to it like a duck to water," she says. "There was no looking back."

Recently, Nirmala was felicitated by her club, the Kerala Toastmasters (KTM), at a function in Koch for being featured in the magazine.

"Nirmala has many achievements to her credit," says KTM president Shawn Jeff Christopher. "She is the first Lady Charter president in Kerala, as well as the first area governor."

Nirmala was given the best area governor award, of District 82, which consists of India and Sri Lanka. She is also the first lieutenant governor-marketing. As a result, she holds the highest position in Kerala. "Nirmala is also the first person to achieve the Distinguished Toastmaster rank," says Shawn. "She has set a benchmark. We have to follow in her footsteps."

At the meeting, Nirmala thanked her mentor, Daniel, apart from many other eminent members. A happy Daniel said, "Nirmala is a person who pursues her goals through relentless efforts. Despite ploughing a lonely furrow, she perseveres, no matter the obstacles."

Says KTM member George Johnson, "Nirmala is the sole reason I joined the Toastmasters. The way she mentored me and the positive energy she imparted, it has always helped me."

Nirmala has spent more than 25 years in the hospitality industry, having worked with the Taj Group of Hotels, the Ramada Resort, Flora Hotel, and the Wonderla Group, among many other assignments. Today, she is the owner or CEO of Infinity Hospitality Services, which focuses on tourism, consultancy and training. Nirmala is also a member of the Institute of Directors, New Delhi, and a managing committee member for several businesses and organisations in Kerala.

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on January 30, 2016 00:26

January 27, 2016

Making a Mark…Yet Again

Despite a small role, Lena makes an impression in the Bollywood box-office hit, ‘Airlift’

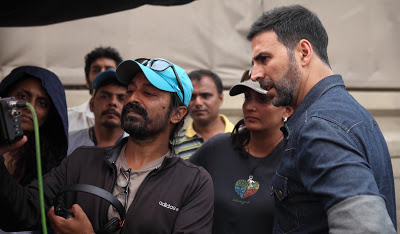

Despite a small role, Lena makes an impression in the Bollywood box-office hit, ‘Airlift’Photos: Lena in a scene from 'Airlift'; Director Raja Krishna Menon (left) with Akshay Kumar during the shoot

By Shevlin Sebastian

In March, 2015, at Ras al-Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, a sandstorm blew up. On the sets of the Bollywood film, ‘Airlift’, director Raja Krishna Menon was thinking of packing up, but it was Akshay Kumar, who plays the hero, who suggested shooting through the sandstorm to create a sense of authenticity.

As a result, Mollywood actress Lena got an opportunity to encounter a sandstorm first-hand. “The only problem was that it took all of us two days to remove all the sand from my hair,” she says, with a laugh. Says a grateful Raja: “The actors were patient and we shot a beautiful scene which, unfortunately, I had to take out in the edit.”

This is Lena’s first role in a Bollywood film. She plays Deepthi Jayarajan, the wife of George Kutty (who is played by Kannada actor Prakash Belawadi). He is forever complaining about all the problems the Indians are facing. ‘Airlift’ is a fictionalised version of the evacuation of 1.7 lakh Indians from Kuwait when Iraq invaded the country in August, 1990.

In the film, Lena has only a few sentences to say. “I was clearly told that there would be very few dialogues, so I was aware before-hand of what I was getting into,” she says.

Says Raja: “Roles are never small or big. Lena took up a challenging role and has blown it out of the park. She is unforgettable as George's wife. She brings life to a very difficult character. I always say quality over quantity.”

Indeed, Lena impressed with her facial expressions. She was able convey powerfully her exasperation at the way her husband is behaving.

In fact, in one of the striking scenes in the film, when George Kutty complains, yet again, Akshay’s on-screen wife Nimrat Kaur lashes out, reducing Kutty to a stunned silence. Again, it is Lena’s shame and embarrassment, which are revealed through the eyes that is eye-catching.

Asked how she got the role, Raja says, “I was looking for a Malayali actor and my casting assistant brought me a clip of a film she was in. Lena was brilliant in the clip, but when I looked deeper, I realised she is quite a big star in Malayalam cinema. Anyway, I spoke with her, explained the part and she agreed to be a part of ‘Airlift’. I am really glad that she did.”

Meanwhile, when asked about the striking difference between a Bollywood and Mollywood production, Lena says, cryptically, “The budget. [Airlift had a budget of Rs 30 crore]. Everything is on a large scale. We cannot even compare.”

Interestingly, Lena has yet to see ‘Airlift’ because she is busy shooting for the Telugu film, ‘Dr. Chakravarty’, where she plays the hero’s wife. “I am told that ‘Airlift’ is doing very well in the box office,” she says. “So I am very happy about that.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on January 27, 2016 21:00

January 25, 2016

When Usha Uthup Danced with Kalpana

(Memories of the actress, who died, aged 51, on January 25)

(Memories of the actress, who died, aged 51, on January 25)Photos: Usha Uthup; Kalpana

By Shevlin Sebastian

Veteran television producer Diana Silvester is in shock. Just two days ago, she had called Kalpana in Hyderabad. She asked the actress if she could attend the inauguration of the new building of the St. Joseph's Bethlehem Church at Chullickal, Kochi, on January 30.

Kalpana promised to get permission from the producer of the Telugu film she was working on. Meanwhile, singer Usha Uthup had already agreed to attend. There is a reason behind the request: at the function, Diana is planning to play the video of the hit song, ‘Palavattam’, which had been sung by Usha. She had also danced with Kalpana for the shoot.

Here's a flashback: at a television studio, in Kochi, on a day in August, 2008, it is difficult to recognise Usha. She is wearing a wig of brown curls and a body-length black gown as well as a dazzling golden necklace.

Standing next to her, in black top and jeans and boots, topped by a black wig, is Kalpana.

Usha and Kalpana move their hands and shake their bodies from side to side, in rhythm to the beat of 'Palavattam', which is being played over the speaker system.

There is an easy camaraderie between Kalpana and Usha. When Kalpana does some quicksilver moves on the dance floor, Usha, who is watching from the sidelines, shouts, “You are a rock star!”

When Usha says, in mock protest, to Diana, “I don’t want to dance next to Kalpana, she makes me look old,” the actress crooks her finger and says, “Come here, little girl.”

During a break in the shooting, Kalpana says this is the first time she is acting for an album song. “The biggest plus is the dynamic voice of Usha Didi,” she says. “And to act with her is a second big plus. Lastly, the director is a lady. So, this song is a collaboration of three women.”

Later, hands-on director Diana keeps coming onto the set from the control room and says, “Kalpana, your lip movements are not synchronising with the lyrics,” or “the expression is not precise.” Kalpana always takes this in a sporting spirit and is ready to do, take after take, to get it right.

As for the song, it has a thumping beat and soaring above it, is the rich velvety voice of Usha. "Who can resist swaying to this song?" says Kalpana, with a smile.

So, it is sad to know that death has snatched away this effervescent actress on the cusp of middle age. Or, as Usha says, from a recording studio at Kolkata, “It was heart-breaking for me to hear the news.”

(The New Indian Express, Kerala editions)

Published on January 25, 2016 19:06

January 24, 2016

A League of His Own

Business magnate Dr. J Rajmohan Pillai, the younger brother of the late Rajan Pillai, has started the Nutking Kerala Tennis League. He has plans to start an all-India league, apart from a tennis academy along the likes of the Britannia Amritraj Tennis (BAT) Academy

Business magnate Dr. J Rajmohan Pillai, the younger brother of the late Rajan Pillai, has started the Nutking Kerala Tennis League. He has plans to start an all-India league, apart from a tennis academy along the likes of the Britannia Amritraj Tennis (BAT) AcademyPhoto of Rajmohan Pillai by Manu R Mavelil

By Shevlin Sebastian

On a humid afternoon in September, 2015, at the Trivandrum Tennis Club, TP Rajaram, the joint secretary of the Kerala Tennis Association was playing a game with Dr. J Rajmohan Pillai, the chairman of the transnational Beta Group, which has a turnover of $2 billion. The group has a major dried fruits and nuts business.

During a break, they had a chat. That was when Rajaram told him about his plans to hold an inter-club championship. “Why inter-club?” said Pillai. “Let's make it bigger. We should get teams from schools, colleges and corporates. That is the only way to unearth the best talents.”

And thus was born the Nutking Kerala Tennis League. For the inaugural league, (November 15 – January 25), there were 37 eight-member teams from all over Kerala, from Kasaragod in the north to Thiruvananthapuram in the south. “We have also encouraged people above 45 to take part,” says Pillai. “Once the parents start playing, the children will definitely follow. I want to create a movement for tennis.”

The league has been divided into four zones. “Each zone had a round robin,” says Rajaram, the tournament director. “The top two will go to the knockout stage. The third and fourth teams will play another knockout for the Loser’s Plate.”

The winner gets Rs 60,000 while the runner-up will collect Rs 40,000. The Plate prize is Rs 30,000 and Rs 20,000 respectively. The total investment is Rs 15 lakhs.

Pillai says that for the next year's league, he will increase the amount substantially, because he has been encouraged by the response. “Tennis has become very popular, thanks to the Grand Slam exploits of Leander Paes, Mahesh Bhupathi, and Sania Mirza,” he says.

Moments after the Wimbledon final in 2015, Rajaram took an autorickshaw in Thrissur town. “The driver spoke to me about the brilliance of Roger Federer and Novak Djokovic,” he says.

Pillai has been brilliant on court, too. In December, 2015, he won the doubles gold with his partner Shashi Bhushan Sharma (a Deputy Inspector-General of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police) at the inaugural Malaysian Open of the seniors circuit of the International Tennis Federation.

But the interest in tennis goes back a couple of generations. “It all started in the early 1960s when my parents used to play tennis at the Cashew Club, Kollam,” says Pillai. “Soon, my elder brother Rajan [Pillai of Britannia Biscuits fame] who is 16 years older than me, began playing. I started at the age of six.

Later, when Rajan settled in Singapore, I would go there and he would provide coaches for me. In fact, his house, on Ridout Road, was one of the few places which had a tennis court in the early 1970s. In the end, both of us developed a passion for the game.”

And in the early 1980s, Rajan (1947-95), who was the chairman of the Beta Trust, contributed $12 million to set up the Britannia Amritraj Tennis (BAT) Academy in Chennai. Later, the academy would produce players like Leander Paes, Somdev Devvarman, Gaurav Natekar and Asif Ismail. There was some good news for Kerala trainees, also.

Jaco T. Mathew won the junior national hardcourt title in 2001 by defeating Somdev Devvarman in the final. Unfortunately, he faded away.

Meanwhile, Pillai has plans to start a second BAT, with an investment of Rs 100 crore. “We are looking for a location in Bangalore,” he says. “Or we might even take over a functioning academy.”He said that his centre would place an emphasis on scientific training. “Otherwise, it would be difficult for Indians to match foreigners in a gruelling five-set match,” says Pillai.

An academy could provide material help, since tennis is not an affordable sport for most people. “If you want to be a pro, you have to spend between Rs 16-22 lakh a year, for travelling, equipment and taking part in tournaments,” says Pillai.

In September, 2016, Pillai will unveil another ambitious plan. His firm Beta Sports is going to hold a pan-India tournament, in the manner of the Indian Premier League. Says Pillai: “So, what was started off by two people at a tennis club could soon become a movement to unify the game in India with one gigantic league!”

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on January 24, 2016 21:08

January 21, 2016

Unexpected Twists and Turns

COLUMN: LOCATION DIARY

COLUMN: LOCATION DIARYScriptwriter/director Rafi talks about his experiences in the films, 'Romeo', ' 'Ringmaster' and 'Aniyan Bava Chettan Bava'

Photos: Scriptwriter/Director Rafi; Dileep in 'Ringmaster'

By Shevlin Sebastian

One day, in 2007, scriptwriter Rafi was on the sets of the film, 'Romeo', at Ottapallam. Suddenly, an unit hand came up to him and said that a young man wanted to meet him. So Rafi called him over.

Anish (name changed) shook Rafi's hand and said, “Sir, when I saw Punjabi House [directed by Rafi-Mecartin, 1998] and saw the financial difficulties of Dileep, I had laughed a lot.”

In the film, Dileep had a small notebook that he kept in his pocket, which contained the details of all the debts that he has to pay back. However, a few years later, Anish was in the same position. “Like Dileep, I also carry a notebook,” said Anish. He then took it out and showed Rafi the money he owed to various people, because of a failed business.

“I can no longer stay at my home, at Kozhikode,” said Anish. “My family is going through a lot of trouble, because the creditors are harassing them. Now, at night, I sleep at railway stations, temples, or bus stands. However, like in 'Punjabi House', I hope to find a benefactor and, who knows, maybe, somebody to fall in love and marry.”

Rafi tapped Anish consolingly on his shoulders and was about to take out his purse. But Anish quickly said, “Sir, I owe in lakhs, so what you give will not make a difference. But when I heard that you were shooting in the vicinity, I just wanted to tell you about all this.”

Like Anish, on another location, at Pollachi, for the film Ringmaster (2014), director Rafi was facing problems. Dileep plays a dog trainer. A Mumbai-based trainer Pradeep (name changed) had come with a dog. However, when the dog was in a naughty mood, he would not obey Pradeep. Three days went past. The dog remained disobedient. No shooting could be done. Rafi, as well as Pradeep, began to feel tense because of the wasted time.

And then, suddenly, Rafi got an idea, to solve the problem. “In the film, there is a film director who is supposed to shoot Dileep and the tricks done by the dog,” says Rafi. “Instead, I changed it and decided the focus would be on a disobedient animal, just like in real life. So the director would say, 'Please make the dog urinate,' and Dileep, despite his best efforts, was not able to do so. This section turned out to be one of the the most humorous moments in the film.”

There have been times when Rafi has felt nervous, just like Pradeep. This was during the shoot, at the Aluva Government Guest House, of 'Aniyan Bava Chettan Bava' (1995) directed by Rajasenan. Rafi and Mecartin had written the script. Soon Rafi heard that the late Narendra Prasad, who was playing Chettan Bava, wanted to see him, after reading the script. “I knew he was a writer and scholar,” says Rafi. “I thought he wanted to scold me for writing an all-out comedy.”

So, Rafi stayed away whenever Prasad's takes were being done. But, one day, by accident, they both came face to face. Prasad said, “For the past few days I have been asking about you.”

Rafi remained silent. “It is a nice script,” said Prasad. “But I have a suggestion to make. When you wrote about the olden times, you spoke about people spending one or two rupees. But in that era, it was one-fourth and one-half of an anna. Would you have any objection if we changed that?”

Rafi agreed immediately. “Prasad Sir never treated me that I was lesser than him,” says Rafi. “I will always have the deepest respect for him.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kozhikode)

Published on January 21, 2016 21:03

The Ups and Downs of the Human Heart

Best-selling author Preeti Shenoy deals with emotions in relationships in her latest book, 'Why We Love The Way We Do'

Best-selling author Preeti Shenoy deals with emotions in relationships in her latest book, 'Why We Love The Way We Do'By Shevlin Sebastian

However, three days later when Preeti opened her bag, she got a shock. The gift was a gold-plated Ganesha. “I was overwhelmed,” she says. Somehow, she managed to trace the young girl on Facebook and conveyed her thanks.

Apart from gifts, Preeti receives thousands of e-mails every month. And they are from people who ask the author for advice on how to go about having relationships. They feel that Preeti is an expert because she has written in detail on this subject in five novels and two non-fiction books, all of which have been best-sellers.

In fact, her just-released book, 'Why we love the way we do', published by Westland, reached No 4 in the best-seller charts within a short while.

It is a collection of her column articles, which she continues to write for a national newspaper. With an average length of 700-800 words, it talks about a wide variety of subjects: finding love, dating, marriage, break-ups, gender differences, communication, infidelity and sex.

So, Preeti is well placed to talk about the trends in middle-class society in India. “The very young are disillusioned about marriage,” says Preeti. “In fact, most youngsters do not want to get married. Because they feel that what they can get from a marriage, they are getting without. Pre-marital sex has become widespread.”

So how do parents react? “Some turn a blind eye,” says Preeti. “Others impose restrictions. But that does not work because children will find 15 other ways to do what they want. The best method is to have an open and healthy friendship with their children. That will enable the children to open up and talk on all subjects, including sex. In fact, a parent can advise their children that it is always better to have sex at 21, when they are mature enough, and not at 15, which is what is happening now.”

As for adults, it has become so much more easy to have an affair. “Today, because of technology, you can sit in India and begin an affair with a person in Japan. The very fact that there were lakhs of Indians on the Ashley Madison [adultery] web site shows that there is an active desire for extra-marital affairs.”

The Bangalore-based Preeti talked about all this on a recent visit to Kochi for a book signing and surprised people when she spoke in fluent Malayalam. “Both my parents grew up in Kerala,” she says. “But I lived outside. But, as children, we would come often to Kerala during our vacations.”

A Goud Saraswat Brahmin, Preeti's life changed in 2006 when her father, KVJ Kamath, passed away, suddenly, at age 66 through a cardiac arrest. “I felt numb because I was very close to my dad and would speak to him every day,” she says. “He was my hero.”

To get over the shock, Preeti began a blog. This turned out to be popular, and thereafter, her writing career took off. Asked to analyse her popularity, Preeti says, “Readers tell me that my style is simple, easy to read, and touches the heart. They have also told me that when they start reading my book, before they realise it, it is over.”

(The New Indian Express, Kochi and Thiruvananthapuram)

Published on January 21, 2016 00:30

January 20, 2016

A Blessed Pair of Hands

Lakshmi Sreedhar makes such wonderful designer fondant cakes that customers are reluctant to cut it, let alone eat itPhotos by Ratheesh Sundaram

Lakshmi Sreedhar makes such wonderful designer fondant cakes that customers are reluctant to cut it, let alone eat itPhotos by Ratheesh SundaramBy Shevlin Sebastian

On a cloudy day in March, 2015, Lakshmi Sreedhar sat, along with her husband and two assistants, in a tempo, her heart beating at express speed. Beside her, covered in plastic and tarpaulin, was her largest creation: a 5' 8” cake. The driver, as instructed, drove the vehicle at the speed of a tortoise. The distance to the hotel from her production unit was eight kilometres. The road was full of potholes, dust, gravel, and, not to forget, speeding cars, buses and lorries.

Thankfully, they made it without a mishap. The cake was in the form of an off-the-shoulder wedding gown. The order was given by a Muscat-based couple for the wedding of their daughter Bhavana Ashok.

From the head till the hip, there were two layers each of chocolate, orange, strawberry and pista. From the hip downwards, there was only icing.

Expectedly, the guests looked dazed. And, more so, the bride. “As soon as I saw the cake, while I was walking down the aisle, I told my mom, 'It's mind-blowing!',” says Bhavana. “Questions ran through my mind: 'Is it possible for someone to create a cake this big and beautiful?'”

But it was not easy to make. Through Whatsapp, the parents sent the photos of their daughter's wedding dress to Lakshmi. She needed the help of two assistants, and her brother, Ram Mohan, but even then it took around 75 hours.

In the end, Bhavana cut a piece from the shoulder and ate it. “It was yummy,” she says.

However, not every order is smooth sailing. Once, Lakshmi was transporting a three-tier 50th anniversary cake from Kochi to Palakkad, a distance of 145 kms in a car. On the highway, her husband, Sreedhar, had to apply the brakes suddenly.

As a result, the top tier just toppled over. “I got a shock,” says Lakshmi. However, she managed to set things right in such a way that nobody, except the customer, noticed anything amiss.

Lakshmi’s speciality is fondant designer cakes. “A designer cake should look good, taste well, and match the desires of the customers,” she says. Most of the parents of children usually opt for Disney figures like Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse. “Recently, parents have started asking for characters from [Hollywood hit animation films] 'Minions' and 'Frozen',” says Lakshmi

She has celebrity customers, too. One of them is Mollywood star Jayasurya.For the promotion of a film called 'Aadu' (Goat), he ordered a cake, which Lakshmi made in the shape of a goat. Says Saritha, Jayasurya’s wife: “It was a 3D cake, flavoured with butterscotch and loaded with crunchy praline. It was so realistic that we did not want to cut it (this happens every time Lakshmi bakes a cake for us). The entire crew was so excited on seeing the cake. And the taste turned out to be delicious. I must say Lakshmi has blessed hands.”

Asked whether she feels sad when a cake is cut, after so much of work, Lakshmi says, “What compensates is the joy in the eyes of the people who eat it.” Her cakes range in price from Rs 4500 to Rs 1 lakh.

Lakshmi puts a lot of emphasis on quality. “I use the best ingredients,” she says. For colours, she imports it from abroad. Her favourites are Americolours and Kopy Kake.

“The problem with Indian edible colours is that there are all types of chemicals in it,” says Lakshmi. “And even if we use a detergent to wash our hands, it will not go off. However, for foreign colours, all you have to do is to wash your hands.”

Undoubtedly, Lakshmi is in the grip of a passion. Her life changed, when, one day, she went looking for a cake for her son Arjun's first birthday. But she could not find any good ones. That was when she decided to make one on her own. And never stopped. In December, 2014, with the support of her husband, and family members, she set up a shop called 'Bakers Walk' in Kochi.

And today, Lakshmi is revelling in the creative work that she does. “It is far more enjoyable than working in a bank, which I did for a few years,” she says.

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on January 20, 2016 00:16

January 18, 2016

Using a Not Much-Used Language

G. Prabha's film, 'Ishti', based on the Namboodiri community, has been made in Sanskrit

G. Prabha's film, 'Ishti', based on the Namboodiri community, has been made in SanskritPhotos: G. Prabha by Ratheesh Sundaram. A scene from 'Ishti'

By Shevlin Sebastian

One morning, in October, 2015, film-maker G. Prabha went, with a sinking heart, to the Perumthrikkovil Siva Temple, on the banks of the Muvattupuzha river in Kerala. It had rained heavily the previous night. And, as he feared, the set was flooded. “The scene was a fire ritual,” says Prabha. “We used buckets to remove the water. But the scene could not be shot in the way that I wanted.”

The film, 'Ishti' (Search for the self), will be released in end-January. And the most unusual aspect is that it is a Sanskrit film. That is because Prabha has a deep love for the language. For more than 20 years, he was a teacher of Sanskrit, as well as the Head of Department, Oriental Languages, at Loyola College, Chennai.

“Till now, the few Sanskrit films that have been made have been religion-based,” says Prabha. “So, I wanted to do a story with a social theme. I felt that this would be more acceptable to the Malayali audience.”

Prabha was inspired by the works of V. T. Bhattathiripad, a critic, whose books highlighted the regressive customs of the Namboodiri community for hundreds of years. Here are some rules: Only the eldest Namboodiri male could marry. In fact, he could have three or four marriages.

“The other brothers could not marry at all,” says Prabha. “They also had no rights to property or wealth. In fact, Bhattathiripad once said that it is better to be born as a dog or a cat than as a second or third brother.”

In the film, set in Kerala, during the 1940s, one of Mollywood's much-respected veterans, Nedumudi Venu plays a Vedic scholar by the name of Ramavikraman Namboodiri, 71.

According to Venu, Ramavikraman's primary desire is to be regarded as a top Namboodiri by doing all the rituals. “He is ready to spoil his relationship with anybody to achieve this,” says Venu.

Ramavikraman's third wife, Sreedevi, 17, is rebellious. She has learnt to read and write, and teaches Raman, the eldest son of Ramavikraman. “This does not go down well with Ramavikraman, who suspects they are having an affair,” says Venu.

A group of Vedic scholars question Raman and Sreedevi and finds cause for suspicion. Thereafter Ramavikraman sends his son out of the house. In response, Sreedevi tells the scholars, “Learning Vedic hymns and wearing the sacred thread are meaningless. First, you should be a human being. It is only then that you can practise truth and righteousness." Following that, she too leaves the house.

Asked why he decided to take up the role, Venu says, “In my early years, I had acted in a Sanskrit play by [the great playwright] Kavalam Narayana Panicker. I am not fluent in the language, but I am familiar with it. 'Ishti' is a rare attempt to do a film in Sanskrit. So, I wanted to be a part of it.”

But there is scepticism about whether a Malayali audience would be able to accept a Sanskrit film. “When the viewers hear the language, along with the visuals, they will be able to understand it,” says Venu. Prabha feels that ‘Ishti’ will attract Sanskrit-lovers in India and abroad.

So, the director is preparing to send his film to various international film festivals all over the globe.

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on January 18, 2016 21:37

January 17, 2016

Doing Their Bit

At an exhibition at Fort Kochi, three artists highlight India’s contribution to the First World War

At an exhibition at Fort Kochi, three artists highlight India’s contribution to the First World War Photos: Surekha by Ratheesh Sundaram; Sarnath Banerjee. Ayisha Abraham. By Nagesh Polali

By Shevlin Sebastian

On the afternoon of January 2, the Bangalore-based artist Surekha is carefully installing sepia-tinted metallic photographs onto slots along a long and narrow table at the Pepper House, Fort Kochi. These are images of the Madras Engineering Sappers Group (MEG) taken during their campaign in the First World War (1914-1918).

This exhibit was part of the show, 'Digging Deep, Crossing Far'. It was curated by the Berlin-based Elke Falat and Juliet Tieke and organised by the Kochi Biennale Foundation along with the Goethe Institut. It highlights India's contribution to the first world war through the works of three Indian artists: Ayisha Abraham, Sarnath Banerjee and Surekha.

Surekha focuses on the contribution of the Bangalore-based MEG. In her research, she was astonished to discover that 92,340 people had gone from the MEG to serve in places like Greece, France, Belgium, Iraq and Africa. There were several communities involved: Mussalmans, Tamils, Parayans, Christians, Moplahs, Telugus, Nayars, and Coorgs. Overall, about 15 lakh people, from all over India, took part in the war.

“The primary incentive was the good salaries,” says Surekha. “The remuneration was Rs 11 a month. For the lower ranks, it was Rs 7. At that time, this was a high salary. Some families did not hesitate to send all their adult male members to the war.” They became members of the infantry, laundry men, cooks and lettermen, among other jobs. But tragically, by the end of the four-year conflict, about 60,000 Indians lost their lives.

However, not many know that the Sappers had a singular achievement. The MEG engineers had invented the Bangalore Torpedo. It is a simple instrument that could blast barbed-wire obstacles from a distance. “In those times wire-cutters took a long time,” says Surekha. “And you risked getting shot when you went close to the wire. The Torpedo was later used in the second World War and other wars.” Incidentally, this discovery by MEG put Bangalore on the world map of war inventions.

Invention or no invention, during the war, the Indians had a difficult relationship with their white superiors. Lt. General Sir Clarence Bird related that a Naik (corporal) told him, “This is a rotten war.” On being asked why, he said, “Who are the people who get killed? Only the young and newly-joined sappers. No subedar or jamedar (junior commissioned officer) is ever killed.”

Meanwhile, the political leadership had hoped that, pleased by India’s participation, Britain would give self-rule at the conclusion of the war. “As a bargaining chip, India gave 8 billion pounds [in today’s value] as a one-time war contribution and kept paying 2.4 billion pounds every year in cash,” says artist Sarnath Banerjee.

Banerjee has done black and white drawings of the sepoys based on his reading of the book, 'If I Die Here, Who Will Remember Me?' (India and the First World War) by London-based author Vedica Kant. In one drawing, he draws a trio of soldiers blowing bagpipes and hitting a drum, but an uninterested British superior looks away from them. In another, he draws four soldiers standing next to each other looking morose and dejected.

“After the war, the Indian soldiers were decommissioned by the British army,” says Sarnath. “However, they were unacknowledged and unsung in their native India. The war did not bring any glory for them. Britain never gave India the promised self-rule. Instead, they promulgated the Rowlatt’s act that led to the further suppression of civil liberties. The British also established special courts which made detention possible without the need for a trial.”

As for the third artist, Ayisha Abraham, one day, a few years ago, at her grandmother's home in Bangalore, she came across a photo of her grandfather, Iswariah Andrews. He was sitting on a bench along with a group of army men. But, through a digital process, Ayisha took another photo but without the faces. “I wanted to draw attention to the construction of a typical group picture taken by an army regiment,” she says. “The hierarchy is very evident.”

However, Ayisha does not know much about the story behind the photo. “My grandfather put a cross beneath the seat where he is sitting, for those back home to identify him,” she says. Andrews, who was a journalist in Mumbai, had served in Mesopotamia for the British Army.

Incidentally, in the 19th century, there were quite a few conversions to Christianity by Indians. Which probably explains the unusual name of Ayisha's grandfather.

All in all, the exhibition gives an insightful look at India’s largely unknown role in the First World War.

(Sunday Magazine, The New Indian Express, South India and Delhi)

Published on January 17, 2016 20:18