Donovan R. Walling's Blog, page 8

January 29, 2011

Going Silent

Recently I saw Asta Nielsen, Denmark's leading silent screen star, in a 1921 version of Hamlet, in which she played the title role as a woman dressed as a man, a fiction created by her mother, the nefarious Queen Gertrude, to ensure the throne and her own position. A brilliant, perfectly apt piano score was created in the moment by Indiana University professor Larry Schanker. It all proved to be a delightful evening at the new IU Cinema.

As in most silent screen dramas, there were moments of unintended hilarity, which served as a reminder that viewers of historical film need what Northrup Frye termed, to enjoy fiction, "a willing suspension of disbelief." This suspension is necessary to enter into the world of fiction, a world in many cases quite unlike the "real" world in which we live at this moment.

To watch a silent film from the Teens or Twenties—a century ago—we also need a willing suspension of modernity, or modern sensibilities. We must mentally turn back our internal calendars to a time before color and talking motion pictures, before television, before airplanes, before the Internet, and all that.

In short, we must put ourselves, as best we can, into the 1920s, in this case, so that we not only understand but also are immersed in the ethos of that bygone era. Otherwise, our understanding of the film—and our enjoyment of what today seems naiveté—will be utterly diminished.

It also must always be remembered that what seems hackneyed in a silent film often was brand new at the time and now is hackneyed only because it has been used subsequently over and over. To understand and appreciate fully the films of any bygone era requires that we learn anew an old vocabulary, much like learning a language no longer spoken and known only by the cognescenti.

Hamlet, in which she played the title role as a woman dressed as a man, a fiction created by her mother, the nefarious Queen Gertrude, to ensure the throne and her own position. A brilliant, perfectly apt piano score was created in the moment by Indiana University professor Larry Schanker. It all proved to be a delightful evening at the new IU Cinema.As in most silent screen dramas, there were moments of unintended hilarity, which served as a reminder that viewers of historical film need what Northrup Frye termed, to enjoy fiction, "a willing suspension of disbelief." This suspension is necessary to enter into the world of fiction, a world in many cases quite unlike the "real" world in which we live at this moment.

To watch a silent film from the Teens or Twenties—a century ago—we also need a willing suspension of modernity, or modern sensibilities. We must mentally turn back our internal calendars to a time before color and talking motion pictures, before television, before airplanes, before the Internet, and all that.

In short, we must put ourselves, as best we can, into the 1920s, in this case, so that we not only understand but also are immersed in the ethos of that bygone era. Otherwise, our understanding of the film—and our enjoyment of what today seems naiveté—will be utterly diminished.

It also must always be remembered that what seems hackneyed in a silent film often was brand new at the time and now is hackneyed only because it has been used subsequently over and over. To understand and appreciate fully the films of any bygone era requires that we learn anew an old vocabulary, much like learning a language no longer spoken and known only by the cognescenti.

Hamlet, in which she played the title role as a woman dressed as a man, a fiction created by her mother, the nefarious Queen Gertrude, to ensure the throne and her own position. A brilliant, perfectly apt piano score was created in the moment by Indiana University professor Larry Schanker. It all proved to be a delightful evening at the new IU Cinema.As in most silent screen dramas, there were moments of unintended hilarity, which served as a reminder that viewers of historical film need what Northrup Frye termed, to enjoy fiction, "a willing suspension of disbelief." This suspension is necessary to enter into the world of fiction, a world in many cases quite unlike the "real" world in which we live at this moment.

To watch a silent film from the Teens or Twenties—a century ago—we also need a willing suspension of modernity, or modern sensibilities. We must mentally turn back our internal calendars to a time before color and talking motion pictures, before television, before airplanes, before the Internet, and all that.

In short, we must put ourselves, as best we can, into the 1920s, in this case, so that we not only understand but also are immersed in the ethos of that bygone era. Otherwise, our understanding of the film—and our enjoyment of what today seems naiveté—will be utterly diminished.

It also must always be remembered that what seems hackneyed in a silent film often was brand new at the time and now is hackneyed only because it has been used subsequently over and over. To understand and appreciate fully the films of any bygone era requires that we learn anew an old vocabulary, much like learning a language no longer spoken and known only by the cognescenti.

Hamlet, in which she played the title role as a woman dressed as a man, a fiction created by her mother, the nefarious Queen Gertrude, to ensure the throne and her own position. A brilliant, perfectly apt piano score was created in the moment by Indiana University professor Larry Schanker. It all proved to be a delightful evening at the new IU Cinema.As in most silent screen dramas, there were moments of unintended hilarity, which served as a reminder that viewers of historical film need what Northrup Frye termed, to enjoy fiction, "a willing suspension of disbelief." This suspension is necessary to enter into the world of fiction, a world in many cases quite unlike the "real" world in which we live at this moment.

To watch a silent film from the Teens or Twenties—a century ago—we also need a willing suspension of modernity, or modern sensibilities. We must mentally turn back our internal calendars to a time before color and talking motion pictures, before television, before airplanes, before the Internet, and all that.

In short, we must put ourselves, as best we can, into the 1920s, in this case, so that we not only understand but also are immersed in the ethos of that bygone era. Otherwise, our understanding of the film—and our enjoyment of what today seems naiveté—will be utterly diminished.

It also must always be remembered that what seems hackneyed in a silent film often was brand new at the time and now is hackneyed only because it has been used subsequently over and over. To understand and appreciate fully the films of any bygone era requires that we learn anew an old vocabulary, much like learning a language no longer spoken and known only by the cognescenti.

Hamlet, in which she played the title role as a woman dressed as a man, a fiction created by her mother, the nefarious Queen Gertrude, to ensure the throne and her own position. A brilliant, perfectly apt piano score was created in the moment by Indiana University professor Larry Schanker. It all proved to be a delightful evening at the new IU Cinema.As in most silent screen dramas, there were moments of unintended hilarity, which served as a reminder that viewers of historical film need what Northrup Frye termed, to enjoy fiction, "a willing suspension of disbelief." This suspension is necessary to enter into the world of fiction, a world in many cases quite unlike the "real" world in which we live at this moment.

To watch a silent film from the Teens or Twenties—a century ago—we also need a willing suspension of modernity, or modern sensibilities. We must mentally turn back our internal calendars to a time before color and talking motion pictures, before television, before airplanes, before the Internet, and all that.

In short, we must put ourselves, as best we can, into the 1920s, in this case, so that we not only understand but also are immersed in the ethos of that bygone era. Otherwise, our understanding of the film—and our enjoyment of what today seems naiveté—will be utterly diminished.

It also must always be remembered that what seems hackneyed in a silent film often was brand new at the time and now is hackneyed only because it has been used subsequently over and over. To understand and appreciate fully the films of any bygone era requires that we learn anew an old vocabulary, much like learning a language no longer spoken and known only by the cognescenti.

Hamlet, in which she played the title role as a woman dressed as a man, a fiction created by her mother, the nefarious Queen Gertrude, to ensure the throne and her own position. A brilliant, perfectly apt piano score was created in the moment by Indiana University professor Larry Schanker. It all proved to be a delightful evening at the new IU Cinema.As in most silent screen dramas, there were moments of unintended hilarity, which served as a reminder that viewers of historical film need what Northrup Frye termed, to enjoy fiction, "a willing suspension of disbelief." This suspension is necessary to enter into the world of fiction, a world in many cases quite unlike the "real" world in which we live at this moment.

To watch a silent film from the Teens or Twenties—a century ago—we also need a willing suspension of modernity, or modern sensibilities. We must mentally turn back our internal calendars to a time before color and talking motion pictures, before television, before airplanes, before the Internet, and all that.

In short, we must put ourselves, as best we can, into the 1920s, in this case, so that we not only understand but also are immersed in the ethos of that bygone era. Otherwise, our understanding of the film—and our enjoyment of what today seems naiveté—will be utterly diminished.

It also must always be remembered that what seems hackneyed in a silent film often was brand new at the time and now is hackneyed only because it has been used subsequently over and over. To understand and appreciate fully the films of any bygone era requires that we learn anew an old vocabulary, much like learning a language no longer spoken and known only by the cognescenti.

January 16, 2011

The Nation's Soul

Religious ceremonies—weddings, funerals, worship services—are forms of theater, whether they are bare-stage productions or lavish with pageantry. This has been understood since ancient days, though the connection perhaps is not as often explored today as in former times. However, there is scholarship in this field, as witnessed by the Journal of Religion and Theatre, published by the Religion and Theatre Focus Group of the Association for Theatre in Higher Education.

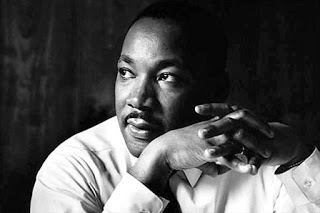

In religious ceremonies, as in theatrical performances, what touches us as witnesses may not be the central action but something incidental to it: a gesture, a word, a verse of song, a melody. They are theater of the soul. This fact was brought home to me on the Saturday preceding the Monday Martin Luther King Day, when I was attending a memorial service for my brother, who had died in December after a battle with pancreatic cancer.

He was a Navy veteran and so military honors were a concluding part of the service. I was sitting near my sister-in-law as the young seaman of the honor guard presented her with the flag, folded in the traditional triangle, "on behalf of the President of the United States…." What moved me at that utterance was not only the honor shown to my brother and the finality of this closing action but also that this honor was rendered on behalf of a President that I like and admire and who is, significantly, nonwhite. Here's why:

The flag ceremony reminded me of a similar honor accorded to my father, an Army veteran who saw wartime service in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam, when he died in 1997. But it recalled an even earlier time, when Dad had been a young serviceman.

For a short time my father had been assigned to work with a black Army officer. They traveled together in the United States at a time before desegregation was widespread, and so part my father's duties was to go into hotels and restaurants ahead of the military detail and ask whether they would serve this officer. My father, who told me of this episode in his life only in later years, never did so without tears welling in his eyes at the injustice done to this officer—a man who served his country with honor and distinction and yet could not walk into just any establishment and be served a meal or given a room and a bed.

The religious theatricality of celebrations of Martin Luther King Day sometimes obscures the small and large realities that ride just behind the stirring language of King's "I Have a Dream" speech. Full civil rights may not yet have been achieved for all individuals. But our country has made progress on this front. When my brother's widow was presented the flag on behalf of this President, my soul was stirred because so much more lay behind those words for our family.

December 20, 2010

Congress: The Musical

You must, of course, imagine the music. Perhaps ruffles and flourishes to precede the actors: the statesmen, or "the lovers, liars and clowns!" as the opening chorus from A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum put it.

Indeed, hand-wringing, wrist-to-forehead angst over gays in the military has been one of the longest running shows in Washington—a tragicomedy of epic proportions—ever since Don't Ask, Don't Tell (DADT) was passed seventeen years ago. Ultimately, the stars in the cast most recently are the Republican senators who crossed party lines to do the right thing—for a change, literally. Senators Collins, Murkowski, Kirk, Brown, Snowe, Voinovich, and reluctantly Ensign and Burr are the glitterati of the moment.

Obama has proven to be a disappointment in the role of President. Unlike Truman, who integrated the military by Executive Order 9981 in 1948, thus summarily ending decades of racial segregation and second-class soldiering by African Americans, Obama chose to push for congressional repeal to end decades of anti-gay discrimination that stretch back in time long before Congress enshrined it in law with DADT. But, then, Obama's been playing Stepin Fetchit to the Republicans for two years, a bit part when he should have been playing the lead.

The real stars of DADT haven't seen much limelight. They are the men and women who "told" and so got quietly robbed of their service careers, and the nation has been the poorer for the all-too-easy dismissal of their talents and dedication for nearly two decades.

Finale: Ta-da! Like magicians collectively whipping open the cabinet (or closet) door, Congress—applause, cheers, whistles!—at last has decided to allow gay men and lesbians to serve their country—as they always have, often with honor and distinction—now openly, without congressionally mandated lying about who they are and who they might or might not love or at least have sex with.

You have to admit that this show has had something for everyone: something familiar, something peculiar; something appealing, something appalling! Certainly appalling.

December 14, 2010

The Art of Being: A Memory

In 2010, when the entire world seems to be represented virtually on the Internet, one would think that everything and everyone can be googled. Occasionally I google my name, partly as ego affirmation, partly to find out where my work is available or has been reviewed. Because I write, I turn up on several pages and literally hundreds of sites. Doesn't everyone?

Apparently not.

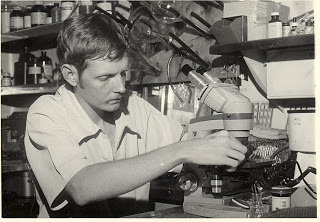

On Sunday, December 12, my brother, Michael Allen Walling, succumbed to pancreatic cancer at the age of 56. He'd been a good kid brother; a good big brother to our sister, Carolyn; a good husband. He'd served in the Navy and gone on to a useful post-military career. (The photo inset shows him in his lab aboard the USS Enterprise aircraft carrier in 1976-77.) So out of curiosity I googled his name.

Nothing.

Not a single hit.

I suppose at some point there might be an obituary that google could find. But that seems such paltry recognition for a life well lived.

Many people—famous, infamous, ordinary—can be googled. Not finding my brother on the Internet, however, reminded me that far more people practice the sometimes not-so-simple art of simply being. They live on, then, not virtually in the electronic ether, but in the memories of those they loved and by whom they were loved.

And that's art enough.