Donovan R. Walling's Blog, page 4

October 15, 2013

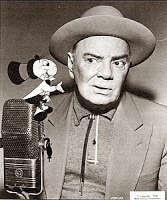

By Jiminy!

Cliff Edwards’ distinctive voice and ukulele strumming are

Cliff Edwards’ distinctive voice and ukulele strumming areworthy of rediscovery by a new generation. Most folks of a certain age now

recall him only as the voice of Jiminy Cricket in Walt Disney’s Pinocchio. His voice is the only one I

want to hear singing “When You Wish Upon a Start.” But Edwards had a long

career before that 1940 animated hit that children still view with delight,

generation after generation. We have to rely on YouTube and Netflix to see and

hear his earlier performances.

He was born Clifton A. Edwards (June 14, 1895 – July 17,

1971) in Mark Twain’s hometown of Hannibal, Missouri, at a time when Twain was

still alive, though not living in his boyhood home by then. Edwards left school

at age 14 and moved to St. Louis and nearby St. Charles, Missouri, where he

entertained in saloons. He taught himself how to play the ukulele (or ukelele,

as it often was spelled in those days), and soon took on the moniker “Ukelele

Ike.”

Edwards got his break in Chicago in 1918 and played the

vaudeville circuit, moving into the big time at the Palace in New York City and

later performing in the Ziegfeld Follies. He was a headliner at the Palace in

1924.

Ukelele Ike made his first record in 1918. In 1924 he was

featured along with Fred Astaire and Fred’s sister Adele in the Gershwin

brothers’ first Broadway musical, Lady Be

Good. Edwards had a number one hit with “I Can’t Give You Anything But

Love” in 1928, followed by another number one in 1929: “Singing’ in the Rain.”

Gene Kelly, who parlayed that song into a hit movie by the same name in 1952

was only 17 when Edwards’ version was a sensation on the airwaves.

Edwards went on to play a variety of character roles in

movies, including His Girl Friday,

the Howard Hawks remake of the play, The

Front Page, a screwball comedy about a hard-boiled newspaper editor and his

eccentric star reporter. The film starred Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell. Edwards

even had his own television show in 1949 and made film and TV appearances

throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Sadly, Edwards fell into alcoholism and drug addiction

toward the end of his life. Broke and largely forgotten by the public, he

succumbed to a heart attack in 1971. But for me and kids across the ages who

have lost themselves in the Disney story of the puppet who wanted to be a “real

boy,” we’ll always hear Edwards with fondness in that singing cricket.

Published on October 15, 2013 00:55

October 1, 2013

Stray Lamb

“I always suspected,” says protagonist T. Lawrence Lamb,

“that an investment banker and a second-story man had a great deal in common.”

The line is from a 1929 novel. It’s prescient, considering what happened in

late October that year—the Wall Street Crash. That debacle tipped the United

States into a ten-year Great Depression, echoed most recently in the crash of

2008, from which the U.S. economy is still recovering. Mr. Lamb is an

investment banker. He has a point. The banker-burglars of 2008 have yet to be held

fully accountable for the financial hardships they and their conservative

political backers imposed on the American people. Recovery is still incomplete,

and rightwing politicos seem bent on ensuring that it ever will be.

Mr. Lamb, however, is a comic character, and the novel by

Thorne Smith in which he appears is merely a bit of fun. It’s called The Stray Lamb. I stumbled on it when I

pulled a long-neglected volume from a dusty corner of my bookshelf, The Thorne Smith 3-Decker, a Doubleday,

Doran and Company edition from 1939. I don’t recall where I picked it up, some

book sale or other, I suppose. But it’s a delightful dive back into the murky

madcap humor of a bygone era.

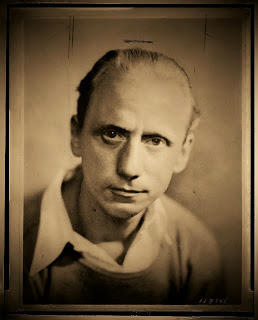

Thorne Smith

James Thorne Smith, Jr. (March 27, 1892 – June 21, 1934),

who wrote under simply Thorne Smith, may be best remembered for two Topper novels. The original Topper (1926) and its sequel Topper Takes a Trip (1932) starred

another banker, Cosmo Topper. Smith’s bankers, saddled with unsatisfactory

wives, invariably get into outrageous scrapes. These novels led to a series of

film and television versions. The first film, Topper, was a Hal Roach vehicle for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1937, featuring

Roland Young and Billie Burke, with a cast that included Cary Grant and

Constance Bennett, who were the bigger stars. An American television series of

the same name began in 1953 and starred Leo G. Carroll as Cosmo Topper. The

pilot and several early episodes were written by Stephen Sondheim.

Thorne Smith’s urbane, zany novels are redolent of the

abandon of the Roaring Twenties. There’s an abundance of sex and alcohol.

Whether sex figured in Smith’s own life, I don’t know. Alcohol certainly seemed

to, by all accounts. He died of a heart attack at age 42.

Mr. Lamb’s tale is the first novel in The Thorne Smith 3-Decker, which also includes the novels, Turnabout (1931) and Rain in the Doorway (1933). The last

broadcast episode of the original Star

Trek television series, “Turnabout Intruder” (1969), was based on Turnabout. Perhaps I’ll read that one

next.

Published on October 01, 2013 04:58

August 5, 2013

When Love Trumps All

Jan Morris recently was voted 15th greatest British writer

Jan Morris recently was voted 15th greatest British writersince the Second World War. Her award winning publications include the 1960

travel book Venice, which has never

been out of print since it first rolled off the presses, and the history

trilogy Pax Britannica. But her

writing must take second place in this commentary to the romantic drama of her

life.

Born James Humphrey Morris on October 2, 1926, the future

Jan Morris became Britain’s leading journalist in the 1950s. After service in

the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers during the closing period of World War II, Morris

was the Times correspondent who

accompanied the British Mount Everest Expedition. Other prominent reporting

followed. In many ways James Morris was much blessed. His successful career

paralleled a successful marriage. In 1949 he had wed Elizabeth Tuckniss, and together

they had five children.

But in 1964 James Morris began a medical transition that

would culminate in a trip to Morocco in 1972, where he underwent sex

reassignment surgery. James became Jan. Whatever interior struggles he had previously

had in some ways at that time transitioned into her struggles to reformulate a

life and a career.

Pax Britannica,

begun by Morris while he was a man, was completed when she was a woman. And

over time there followed a trove of other triumphs in literature, from travel

books (The Matter of Wales, Trieste and

the Meaning of Nowhere) to essays (Among

the Cities, O Canada!, Contact! A Book of Glimpses), history, fiction, and

memoir.

The British government had forced Elizabeth and her husband

to divorce following Jan’s transition. At the time same-sex union were not

permitted. But the couple never stopped living together and loving one

another. Recently, on May 14 this year, Elizabeth

and Jan tied the knot again in a Britain where same-sex civil unions are now sanctioned.

“I

made my marriage vows 59 years ago and still have them,” Elizabeth told the Evening Standard, following their

government-sanctioned reuniting. “We are back together again officially. After

Jan had a sex change we had to divorce. So there we were. It did not make any

difference to me. We still had our family. We just carried on.”

For

Elizabeth and Jan, now in their 80s, love has consistently trumped sexual

identity, convention, and all of the sturm und drang that so pervasively

accompany the politics of sexual expression. Here is a case of two humans

loving one another over the course of a lifetime, everything else be damned.

Published on August 05, 2013 05:30

July 18, 2013

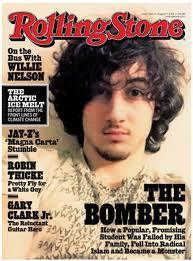

The Art of Vilification

In

Inthe last day or two Rolling Stone magazine has been taken to task by

many observers for publishing a cover photo of accused Boston bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. Some major magazine sales outlets have

refused to sell the issue.

At

root is emotionalism, which, although it is understandable, must be tempered in a

society that claims and expects to be governed by the rule of law. The

operative term is accused. In the American justice system a person

stands innocent until proven guilty. But Dzkokhar Tsarnaev has been judged by

the court of public opinion. In that court, he’s already guilty.

If

Rolling Stone should be taken to task, it would be more justifiably

because the magazine is pandering to public vilification of this accused

bomber, not by putting his photograph on the cover but by underlining it with

the words “The Bomber.” The magazine has already judged him guilty, like much

of the public.

That the photo has caused such outcry seems disingenuous.

Perhaps the outcry is because Rolling Stone is more often thought of as

a popular culture magazine than a serious commentator on hard news. Perhaps it

is because the photo is not the usual image of a bedraggled prisoner awaiting

trial that has become a standard form of public vilification, often of those

not yet judged to be guilty but, like Dzkokhar Tsarnaev, awaiting their day in

court.

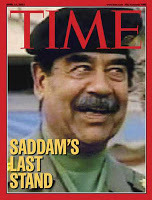

Taken merely as subjects of current interest, accused and

convicted criminals, murderers all, are frequently featured on magazine covers.

It is a stock device of longstanding for Time

magazine in particular. In 1943 Time

featured a heroic portrait of Russian dictator Josef Stalin and named him its

Man of the Year. More recently, in 1999, Time

featured the smiling faces of Eric Harris

and Dylan Klebold. They look like fresh-faced teenagers, but they are

better remembered as the Columbine High School shooters. Saddam Hussein, Adolph

Hitler, Muammar Gaddafi, Idi Amin, Timothy McVeigh, the list goes on, foreign

and domestic—all have been featured on magazine covers.

This instance of featuring a killer, accused or convicted, is

not a one-off for Rolling Stone. In

1970 Rolling Stone put mass murderer

Charles Manson on its cover; Life had

done the same the previous year. Does putting Dzkokhar Tsarnaev on Rolling Stone make him a “rock star,” as

some have commented? My guess is that it doesn’t have that effect for most

viewers, any more than putting Saddam Hussein’s smiling face on the cover of Time made him into a kindly father

figure.

The old saw is that a picture is worth a thousand words. What

those words are must be conjured up in the mind of the viewer. Rolling Stone’s use of this particular

image of the accused Boston bomber feeds the imagination of different people in

different ways. Those who have already judged Dzkokhar Tsarnaev guilty find the

image too positive, too apparently innocent. The art of vilification demands a

darker vision.

Published on July 18, 2013 08:00

June 30, 2013

Casual Racism

As several states raced to find ways to disenfranchise

As several states raced to find ways to disenfranchiseminority voters in the days following the Supreme Court’s decision regarding

the Voter Rights Act, the Paula Deen debacle put paid to the notion that some

sort of sea change has occurred and racism is no longer an issue in the United

States. Racism clearly is still an issue. TV celebrity chef Deen’s tribulations

have entertainment value in today’s scandal-driven media, but her missteps

belie deeper societal problems. Racism has moved from the blatant to the

casual.

For example, in June the U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD) released Housing

Discrimination Against Racial and Ethnic Minorities 2012. When minority

buyers and renters show up, “This

study finds that minority homeseekers whose ethnicity is more readily

identifiable experience more discrimination than those who may be mistaken for

whites.” The study notes that discrimination has diminished, but it has not disappeared

in communities across the nation. Researchers included more than 8,000 tests in

a nationally representative sample of 28 metropolitan areas.

Folks like the

doyen of Southern comfort food will smile in your face, but don’t turn your

back. Sure, Paula Deen probably wouldn’t pick up a handy butcher knife and stab

you. But there are subtler ways for casual racists to damage those who are not

like them. Like the minority homeseekers in the HUD study, you simply will be

shown fewer properties or have a harder time getting an appointment. The racism

is still there—less obvious, not gone.

“I is what I is,”

Deen lamented with faux folksiness in a tearful Today Show interview. Well, Miz Paula, you might as well have

trotted out that old saw, you know, about how “some o’ mah best friends is

black folk.” Uh huh. The real problem is, you is a racist. Personally, I would rather Deen had said something

along the lines of “I am working on overcoming the racism in which I was

raised, but sometimes stupidity drops out of my mouth before I can stop it, and

I’m sorry.” That might, or might not, have been a more honest response. After

all, Miz Paula also added, “I’m not changing.”

For

sensationalism seekers, a real apology wouldn’t have been as entertaining as

Deen’s weepy self-justifying meltdown on national television. But it would have

gone further to rehabilitate Deen’s image. And a more responsible, less

emotional approach also would have acknowledged that racism, though less ardent

than in prior years, still exists—and still negatively affects every American

regardless of race and ethnicity in some way. Sadly, deny or defend are more

prevalent strategies among casual racists, as we are now likely to see in

issues of voter discrimination as well, following the High Court’s decision on

the Voting Rights Act.

Published on June 30, 2013 11:19

May 28, 2013

Why I Paint

Detail from a recent painting.

My walls are full—some might say overfull—of paintings,

prints, drawings, and photographs. Many of the paintings are my own. I rarely

sell one, though I give one away now and then when I think it won’t be taken

amiss. I certainly don’t need to paint any more paintings, and I don’t think

I’m much good at painting in any case. So why do I paint?

The easy answer is that I still enjoy it—when I don’t hate

it. Painting challenges me. I never seem to be able to create the image in my

head on canvas, but I’m often pleasantly surprised by what does appear. And if

I’m not pleased, I can paint over it. A good number of my paintings have other,

less successful works lurking beneath the surface. I like pushing paint around.

Attacking a canvas is a visceral aesthetic. Often I do so to the accompaniment

of rock music played loudly. Painting can be a total-body workout, feet

shuffling like a boxer’s, hands slashing paint, mind running this way and that,

contemplating moves like a chess player.

Mid-19th century,

the Académie des Beaux-Arts dominated French art and therefore art writ large.

The Académie was the embalmer of traditional painting standards: historical,

religious, and mythological subjects, portraits, all carefully idealized

realism in somber colors and no visible brush strokes.

Then along came

the Impressionists, who liked color and everyday scenes—and visible brush

strokes. Perhaps they also rebelled against the Académie because at mid-19th

century the advent of photography was threatening to make realistic painting

obsolete. Once freed from the constraints of the Salon, painting boarded a

speeding train toward Modernism, which pervaded the 20th century. That was the

train I got on about a half-century ago.

I’ve never

entirely settled on a style of painting. The images I create veer toward

Modernity but are as likely to be sidetracked by Impressionism. Put two of my

paintings side by side and one might wonder whether they were created by

different artists. My only defense is that, yes, they probably were. Each time

I load a brush and approach a canvas, I am someone a little bit different from

the person who last painted in my shoes.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little

statesmen and philosophers and divines.” I make no judgment about whether I am

foolish; I only know that I am not consistent. At least, not in painting. But I

like doing it anyway. It’s good exercise.

Published on May 28, 2013 14:28

March 30, 2013

Little Resurrections

Diana

Resurrectio in

Latin is a universal concept of coming spiritually or physically back to life

after death. It is the central theme of the Christian Easter, which will be

tomorrow this year. I don’t believe Jesus physically arose from the dead, but I

do believe in resurrection both in the larger spiritual sense and in the everyday sense.

Everyday, or little, resurrections are acts of will.

Two days ago my mother-in-law, along with several family

members, took the ashes of my father-in-law to sea off the coast of southern

California. My father-in-law was 86 when he died a couple of weeks ago.

Twenty-two years ago, their daughter Diana, my wife of 23 years, died at age

43. It struck me this week that if I lived to my father-in-law’s age of 86, my

life will have been divided equally between the years before and after my

beloved wife’s death.

When Diana died, so did I. So did her parents and others.

And so did our children: our daughter in college at the time, our high school son, and our

three-year-old son. Since that dreadful moment of loss, we have lived on, as

others have done following moments of spiritual death. Our lives are acts of

resurrection. Each day, we will ourselves to come back to life.

“Faithfulness to the past can be a kind of death above

ground,” wrote Jessamyn West, an Indiana Quaker and author of The Friendly Persuasion. “Writing of the

past is a resurrection; the past then lives in your words and you are free.”

Life, for me and I suspect for many others, is a series of

little resurrections. By writing this reflection today, Diana, and my

father-in-law, live on. And in this little resurrection I also am free to live again.

Published on March 30, 2013 00:53

March 18, 2013

Houdon and the American Collective Memory

Recently my family and I embarked on a spring vacation road

trip that included spending time in Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Thomas

Jefferson’s home, Monticello. The trip was, partly by intention and partly by

accident, a kind of civic education tour. One persistent memory for me has

become the artistry of Jean-Antoine Houdon, the French neoclassical sculptor.

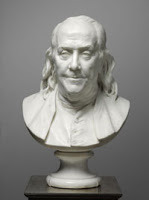

Houdon (born at Versailles, March 20, 1741 – died in Paris,

July 15, 1828) excelled at portraying with classical realism the great figures

of his day. At the Philadelphia Museum of Art I encountered his bust of

Benjamin Franklin, which stands at the center of small rotunda gallery.

Franklin did not sit for Houdon, who apparently drew on memories of having seen

the American statesman at various times when Franklin was representing the

fledgling United States in France from 1776 to 1785. A 1778 marble version of

the bust can be viewed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Houdon

exhibited a terra cotta version at the French Royal Academy Salon in 1779. (A

1778 terra cotta bust of Franklin can also be seen at the National Portrait

Gallery in Washington, D.C.)

Houdon actually met Franklin in 1783. The Philadelphia

marble bust dates from 1785 and is the most detailed. It has become the iconic

portrait in the round of the American statesman. At eye level one can almost

imagine standing before the great man himself.

Houdon’s plaster bust of George Washington stands in the

National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Franklin invited Houdon to visit

the United States, specifically so that Washington could sit for the artist. However,

in the National Gallery the more remarkable images may well be two busts of the

Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire, whose ideas helped shape the thinking of

many of America’s founders. Voltaire was a favorite model for Houdon. The two

marble busts in the National Gallery show Voltaire with and without a perruque

(wig) but both with a wry smile, consistent with Voltaire’s fame for his wit.

At Monticello visitors can see Houdon’s bust of Thomas Jefferson,

a terra cotta-patinated plaster on a marble plinth. Jefferson met Houdon while the former was minister to France from 1785

to 1789. Before leaving France at the outbreak of the French Revolution, Jefferson

acquired ten or twelve terra cotta-patinated plaster busts of figures such as

George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, the Marquis de Lafayette, and Voltaire

for Monticello. Jefferson also sat for Houdon himself and brought back several

plaster versions of his own bust to give to friends.

Houdon worked

from life, portraying the noteworthy figures of his day with extraordinary

skill and accuracy, thus giving future generations the images that form the

American collective memory of its founding generation. What a marvelous gift

these images are for today and for the future.

Published on March 18, 2013 06:23

January 15, 2013

No. 1 Connection to Indiana

I had to chuckle when I read the latest in Alexander McCall

I had to chuckle when I read the latest in Alexander McCallSmith’s popular and thoroughly delightful series of gentle mysteries featuring

the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency in Botswana. Not only did the novel’s various little

problems, twists, and turns offer the usual good fun but there also was an

Indiana connection of a surprising and unusual sort.

Like the earlier novels, this 2012 one, titled The Limpopo Academy of Private Detection,

featured the familiar cast of characters: founder and principal detective at

the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, the redoubtable Precious Ramotswe; her

assistant—oops, associate—Grace

Makutsi; Mma Ramotswe’s husband and proprietor of the Tlokweng Road Speedy

Motors garage, Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni; Mma Makutsi’s new husband and proprietor of

the Double Comfort Furniture Store, Mr. Phuti Radiphuti; and others well known

to readers of the series. But there was a new character—and a special one at

that.

Since the beginning Mma Ramotswe and her associate have been

guided in their efforts at detection by a book titled The Principles of Private Detection, which is full of pity sayings

and sound advice. Mma Ramotswe and Mma Makutsi can quote sections of the book

verbatim with easy familiarity. Now, who should appear in Tlokweng Road but the

author himself, a modest, unassuming man, Clovis Andersen. Needless to say,

Andersen is treated like a visiting dignitary, though he is anything but; and

Mma Makutsi is particularly star-struck.

Andersen, it transpires, is from Muncie, Indiana, and even

went to college in Bloomington. Were I to suspend my disbelief, I might well

wonder where the fictional student Andersen walked and lived. Did he frequent the same

coffee shops where I am prone to read mysteries over an afternoon cup of brew? For

those who have not yet read this latest offering in the popular series, I won’t

say more about Clovis Andersen, as to do so might spoil the fun. And this book

is fun, as is the entire series.

Published on January 15, 2013 03:37

December 4, 2012

St. Nick Redux

It’s that time of year again—a time for newbies and

hucksters to reinvent Christmas, repurpose, reuse, refresh. The rest of us, I

suspect, may be content merely to revisit some version of Christmas past.

One version that is a particular favorite is the one given

life in Clement C. Moore’s poem, known variously as “A Visit from St.

Nicholas,” “Twas the Night Before Christmas,” and simply “The Night Before

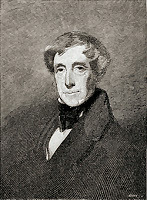

Christmas.” Clement Clarke Moore (right, July 15, 1779 – July 10, 1863) must be given

credit for shaping our modern-day Santa Claus, his basic physical appearance

and character, white beard and jelly belly and all that. However, like

Shakespeare, Moore’s authorship has been called into question. Some have

suggested that the real author could be Henry Livingston, Jr., a distant

relative of Moore’s wife. I’ll leave that debate for scholars to argue. The

fact of the poem—originally published anonymously in 1823—is sufficient for the

season.

St. Nicholas, “a right jolly old elf,” offered at the time a

counter-character to the then-popular image of a venerated saint—Father

Christmas in Britain or Sinterklaas in Holland—who traditionally turned up on St. Nicholas Day,

usually December 6 (though December 19 in most Orthodox countries). Across

Europe that day is still reserved for children, and St. Nicholas is a bringer

of gifts. Our Santa Claus starts with this tradition. Moore reinvented the holy

father as the tubby, magical fellow who cruises around the world in a flying

sleigh pulled by eight tiny reindeer—we know their names: Dasher, Dancer,

Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Donder, and Blitzen. Donder (sometimes Dunder or

Donner) and Blitzen (or Blixem) are a nod to the Dutch words for “thunder” and

“lightning.” (Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer didn’t appear until 1939.)

Since the

mid-1800s Moore’s St. Nick has shaped our modern Christmas mythology.

Naturally, this version also has been a frequent subject of parody,

reinvention, and reiteration. The poem was crafted as a silent movie in 1905

and inspired Tim Burton’s 1993 animated film, The Nightmare Before Christmas. Singer Perry Como recorded a spoken

version in 1953, although the poem had been set to music in 1942 and has since

been recorded by various artists, including Dave Seville, who included it in a

1963 album, Christmas with The Chipmunks,

Volume 2.

All that aside, the poem is still fun to read in its

original version, preferably to a child. Or record it and send it to all the

grandchildren. Or find Basil Rathbone’s 1939

recording. Or Perry Como’s. Or Jack Palance’s in 2001. You get the picture.

Published on December 04, 2012 17:07