Donovan R. Walling's Blog, page 3

October 26, 2014

Veidt Dances an Expressionist Ballet

My interest in Conrad Veidt was tipped by a Halloween-season showing of the 1924 silent thriller, The Hands of Orlach, for which Dennis James provided live organ accompaniment at the Indiana University Auditorium. Veidt’s career spanned a quarter century, beginning in 1917 with the silent movies and into the talkies, ending at his death in 1943 at age 50.

Hans Walter Konrad Weidt was born in Berlin, Germany, on 22 January 1893. He was drafted into the German Army during World War I and saw action in the Battle of Warsaw but contracted a serious illness that subsequently earned him a discharge in 1917. That year he returned to Berlin to pursue an acting career. He would eventually appear in more than a hundred films.

One of his earliest, most memorable performances was in the classic German Expressionist film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, in 1920.Veidt played the sleepwalker Cesare to Werner Krauss’ Dr. Caligari. By the end of the decade, he was making movies in Hollywood as well.

Veidt was vigorously opposed to the Nazi regime. When Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels began a purge to rid the German film industry of Jews and liberals in 1933, Veidt and his third wife, Ilona, a Hungarian Jew, emigrated to England. Throughout the World War II era, he donated large amounts of his personal fortune to the British war effort.

He became a British citizen in 1938, although he and Ilona moved to Hollywood in the early 1940s. Ironically, his best-known Hollywood role was as a Nazi officer, Major Heinrich Strasser, in the 1942 Humphrey Bogart-Ingrid Bergman film, Casablanca.

Veidt suffered a massive heart attack while playing golf in Los Angeles and died on 3 April 1943.

Handsome, gaunt, and exuding an aura of anxiety, sometimes ecstatic and sometimes maniacal, Veidt was at his best in the German Expressionist films of the late Teens to early Thirties. In The Hands of Orlach, in which he plays a pianist whose injured hands are replaced with those of an executed murder, according to critic Lotte Eisner, Veidt “dances a kind of Expressionist ballet, bending and twisting extravagantly, simultaneously drawn and repelled by the murderous dagger held by hands which do not seem to belong to him.”

It was a pleasure to rediscover not only the tantalizing stylizations of the German Expressionist silent films but also to witness one of the masters of that art at work.

Published on October 26, 2014 14:50

October 7, 2014

Professor Media*

From the broadsheets and banned theater of America’s founding era to TV news, Twitter, and sitcoms today, media have been our professors, teaching us about our world and shaping how we think about and respond to important issues. Mass media are more directly educative for most adults than any type of formal schooling. Increasingly, as the current mania for standardized testing narrows the school curriculum, media also are surpassing classroom teachers as our children’s most influential educators.

This media-education interconnection is complex and often problematic. While media have helped to shape progress on some issues of importance to American democracy, they also have contributed to ignorance and misunderstanding. The First Amendment protects freedom of expression, but it does not ensure truth. Societally reflective sitcoms, for example, have paved the way for progress on social issues, from civil rights to marriage equality. But biased political advertising and propagandistic “news” have contributed to political stagnation and the growing gap between rich and poor.

Media are seductive. We spend hours on “screen time.” Those who control the media well understand that what is portrayed and how it is framed shapes socially shared knowledge. The rise of corporate oligarchy in the United States has been achieved, in part, through concerted propaganda passed off as truth. What this means is that, if we are to reclaim American democracy, greater attention needs to be paid to the educative power of media—and not merely to the traditional forms (movies, radio, television) but to new media that we carry with us in our mobile phones and tablet computers. According to a Pew study last year, one in three Americans gets news through Facebook.** And two-thirds of adult Americans use Facebook.

For media consumers—which means everyone, children and adults—it has never been more important to exercise effective credibility strategies, such as critically examining claims of “truth.” A quote attributed to American economist Thomas Sowell is apt: “If people in the media cannot decide whether they are in the business of reporting news or manufacturing propaganda, it is all the more important that the public understand that difference, and choose their news sources accordingly.” However, such understanding must be taught, not just in schools but through the media themselves.

Principles of journalism must cross all platforms, from sitcoms to news reports. Are “facts” accurate, credible, verifiable, contextually appropriate, and unbiased? Whether the purveyor is a talking head or a comic character, how is “truth” situated? If we subscribe to the biblical admonition that the “truth will set you free,” then we also must invoke the first part of that quotation about “knowing the truth,” which is the real challenge, regardless of the context.

*This essay is cross-posted on two blogs: Advancing Learning and Democracy (http://advancinglearning.blogspot.com) and Arts in View (http://artsinview.blogspot.com).

** http://www.journalism.org/2013/10/24/the-role-of-news-on-facebook/

Published on October 07, 2014 07:30

August 11, 2014

Three Takes on 20th Century Art

A recent vacation swing through Wisconsin and back by way of Chicago offered an opportunity to visit three art institutions, each with a focused exhibit worth seeing.

In Sheboygan, Wisconsin, at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, I encountered a retrospective titled “Arts/Industry: Collaboration and Revelation,” highlighting the 40th anniversary of a program involving mainly ceramic artists and the large Kohler Company, known for its innovative kitchen and bathroom fittings and fixtures. Having lived in Sheboygan from 1970 to 1991, I recognized a few of the early works on view. The program has produced an astonishing variety of ceramic arts, through artists in residence at the factory.

In Milwaukee, the featured exhibit at the Milwaukee Art Museum was “Kandinsky: A Retrospective,” featuring paintings and other works by Russian-born Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) from the large collection at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The works on view span 1900 to 1944, from Kandinsky’s experimentation with Art Nouveau through the Bauhaus years and culminating with his flirtations with Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism. (Fragment I for Composition VII from 1913 is shown above.)

Finally, at the Chicago Art Institute, I was happy to visit “Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938,” billed as the “first major museum exhibition to focus exclusively on the breakthrough years of René Magritte” (1898-1967), a Surrealist responsible for some of the 20th Century’s most engaging images. From works on paper that first gained him recognition in Brussels, the exhibit moves forward through the Paris years when he was in contact with fellow Surrealists, such as André Breton, Salvador Dali, and Joan Miró. The exhibit concludes with works made in London and Brussels between 1937 and 1938, including the iconic Time Transfixed, in which a train engine emerges from a fireplace.

All three exhibits showcase aspects of 20th Century Modernism, from the eclectic mix of artists’ ceramic works in a 40-year show spanning late Modernism to Postmodernism, to Kandinsky’s experiments in Art Nouveau and Abstract Expressionism, and finally to Magritte’s emergence from early Impressionistic works to his solid place in Surrealism. A vacation that includes such an abundance of visual images is truly a marvel of coincidence.

Published on August 11, 2014 08:40

June 30, 2014

Have You Ever?

Much of my poetry draws on life experiences, which is doubtless true for most poets (a distinction to which I have only a passing, rather dubious claim). The following poem, however, is starkly autobiographical and intended, I suppose, as a morsel of "tough love" or "straight talk" to someone who is going through a hard time of some sort.

Have You Ever?

Have you ever followed the ambulanceAnd waited for the doctor, who shook his headAnd said,Your wife is dead?Your love, your light, your reason for lifeIs dead?I have.

Have you ever gone home at dawn to tellYour three-year-old son and his fifteen-year-old brother,Mom is dead?Do you hear what I said?Then called your daughter, your dad, your loved one’s parentsWith the sad news?I have.

Have you ever waited in an exam roomWaited for the doctor, who shook his headAnd said,You have cancer?Have you felt the jolt of fear for yourself, for your kidsCourse through?I have,Not one time but two.

So, yes, by all means, tell me about your terrors,Your fears and misgivings, the sharp teeth that gnawAt your mind.Tell me.I know where you’re at, where you’re going.I’ve been there.I have.

But don’t tell me you cannot survive,That it’s all too much, that you can’t stand the pain.You can.You know why?Because I’ve been through your hell and I’m still alive.I have survived.I have. You will, too.

Have You Ever?

Have you ever followed the ambulanceAnd waited for the doctor, who shook his headAnd said,Your wife is dead?Your love, your light, your reason for lifeIs dead?I have.

Have you ever gone home at dawn to tellYour three-year-old son and his fifteen-year-old brother,Mom is dead?Do you hear what I said?Then called your daughter, your dad, your loved one’s parentsWith the sad news?I have.

Have you ever waited in an exam roomWaited for the doctor, who shook his headAnd said,You have cancer?Have you felt the jolt of fear for yourself, for your kidsCourse through?I have,Not one time but two.

So, yes, by all means, tell me about your terrors,Your fears and misgivings, the sharp teeth that gnawAt your mind.Tell me.I know where you’re at, where you’re going.I’ve been there.I have.

But don’t tell me you cannot survive,That it’s all too much, that you can’t stand the pain.You can.You know why?Because I’ve been through your hell and I’m still alive.I have survived.I have. You will, too.

Published on June 30, 2014 16:54

May 28, 2014

Remembering Maya Angelou

I heard the sad news about Maya Angelou’s death at age 86 the day after I took a German friend (who’d been a high school exchange student with us about a decade ago) to Cincinnati, Ohio, to visit the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. In the gift shop there, I bought the Complete Collected Poems of Maya Angelou. I had other books by her but not that one. It seems extraordinary that she was much on my mind at just this time.

A few years ago I worked with a co-editor on an anthology project titled Why Civic Education Matters, published by the Center for Civic Education (http://new.civiced.org/). To include an essay by Maya Angelou inthe book, my co-editor Greg Bernstein conducted an interview with the busy author and sent me the transcript. My task was to take the raw material and craft an essay. The challenge, which I quite enjoyed, was to capture the essence of Maya Angelou’s responses and transform them into a coherent narrative, all the while being sensitive to her unique voice. I have to assume that when she was shown the edited work, she was satisfied.

Prior to developing the anthology, of course, I had gained an advantage by having seen Maya Angelou in films and on television. I had heard that wonderful, distinctive voice many times. Best of all, I had the pleasure of seeing her in person when she spoke at the Indiana University Auditorium. That particular evening was nothing short of magical. Maya Angelou at 80-plus years of age held a standing-room-only audience of more than 3,000 totally enthralled for an hour and a half. She talked, read, recited, sang, and even danced her way into the hearts of everyone present. It was an evening I’ll never forget.

Published on May 28, 2014 11:28

March 13, 2014

Lush Melodies with an International Beat

Not long ago my partner and I had the pleasure of going to a concert by Pink Martini, a delightfully eclectic ensemble—a “little orchestra”—formed in the mid-1990s by pianist Thomas Lauderdale in Portland, Oregon. Shortly afterward, he invited fellow Harvard classmate China Forbes to join the group as its lead vocalist. Together they wrote—and continue to write—songs that the group plays interspersed with standards and little-known pieces from a mix of genres: classical, jazz, and pop.

Lauderdale and Forbes’ first song, “Sympathique,” was a sensation in France, nominated as “Song of the Year” at that nation’s Victoires de la Musique Awards. Although Lauderdale says that the group is “very much American,” it plays all over the world. The songs are as likely to be sung in Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, or Japanese as in English. Their concerts are a rollicking mix of languages, moods, and rhythms.

When they played Indianapolis last month at the historic Murat Theater (now Old National Center), the concert also included the Von Trapps, four great-grandchildren of Captain Georg and Maria von Trapp of Sound of Music fame. The “kids,” formerly the Von Trapp Children, are all roughly college age and produce a fine a cappella sound, singing a mixture of old pop (ABBA), Sound of Music songs, and newer works. August, Amanda, Melanie, and Sofia are the grandchildren of Werner von Trapp (“Kurt” in the movie). They have also worked with a variety of orchestras, including symphonies in Atlanta, Detroit, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Cincinnati, and the Boston Pops.

Pink Martini and the Von Trapps collaborated on a new album this year. Titled “Dream a Little Dream,” it was released on March 4. At the concert in Indianapolis, the group performed the title song, which listeners of my generation associate with Cass Elliot. It was the title song of her first solo album after the breakup of The Mamas and the Papas and was a big hit in 1968. Few remember that the song itself actually dates from about 1931 (music by Fabian Andre and Wilbur Schwandt, lyrics by Gus Kahn). It was first recorded by Ozzie Nelson in February 1931 and ranks as a standard.

Pink Martini under Thomas Lauderdale’s leadership continues to offer concerts rich in lush melodies and variety. Every one is a celebration.

Published on March 13, 2014 06:24

January 5, 2014

Ruminations on 1623

January is the month of my birth. This year, for no particular reason, it has occasioned some reflections about my family history. The first American Wallings arrived on this continent in 1623 at Plymouth Colony, which today is the town of Plymouth, Massachusetts. They were Ralph and Margaret Wallen (a variant spelling in a time before spelling became more standardized). They embarked from London, probably at the port of Southhampton. I don’t know whether they traveled first class or steerage. My bet would be on steerage, as we seem always to have been a working class family. Two ships from England arrived that summer at New Plymouth, as the Plymouth Colony was then known: the Anne and the Little James.The Anne, which arrived in July, carried the Wallens.

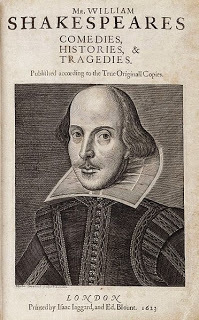

The year 1623 was eventful—but, then, isn’t that true of all years. Back in England, King James I sat on the throne, some twenty years into his reign with a couple more to go before his death in 1625. William Shakespeare had died seven years earlier, in 1616, but 1623 was the year that Martin Droeshout’s engraved portrait (above) of the playwright appeared on the First Folio, published in November that year and containing thirty-six plays, half of which had not previously been published. Shakespeare’s widow, Anne Hathaway, had died on August 6, scarcely three months earlier.

On the continent of Europe, active artists included Bernini and Caravaggio in Italy; Rembrandt, Rubens, and Anthony Van Dyke in the Netherlands; and Velázquez and El Greco in Spain. The Renaissance had given way to the Baroque period, and the Dutch Golden Age was in full swing. Europe also was in the midst of the Thirty Years War (1618-48), although England remained largely on the periphery.

Matters were not without interest in the New World. In November of 1623 a fire destroyed several buildings at Plymouth Colony. This disaster, however, did not deter the colonists from celebrating the settlement’s actual “first” Thanksgiving. The First Thanksgiving of legend, of course, occurred in 1621, almost a year after the Mayflower landed, bringing the first settlers. However, that event would not have been known as “Thanksgiving” to them. It was more properly a simple harvest festival, celebrated by the 53 surviving colonists and some 90 members of the Wampanoag tribe of Chief Massasoit. The first Thanksgiving known as such happened in 1623, in response to the good news of the arrival of additional colonists and supplies, namely on the Anne and the Little James. I imagine that Ralph and Joyce Wallen took part in the celebration.

Ralph and Joyce had married in 1620. By the time they arrived in Plymouth Colony, Ralph was thirty-three and Joyce was twenty-eight. Four years later, in 1627, the first of my direct forebears to be born on North American soil, arrived. He was named Thomas, the first of several of my American ancestors to bear that name. Unfortunately, he was still a teenager when he was orphaned, as Joyce died in 1643. Ralph preceded her in death by a decade, succumbing in 1633, at the age of forty-three.

Thomas would live on to marry twice, to move to Providence, Rhode Island, and to pursue the family’s nomadic tradition, which has continued to my own time. While I reflect in my natal month that life has been an interesting journey on a personal level, I am conscious that the journey of my family over the course of at least the past four centuries has been even more interesting. My genealogical investigations to date have barely scratched the surface. There’s an implicit New Year’s resolution in that.

Published on January 05, 2014 11:58

December 16, 2013

Remembering Peter O'Toole

What a wonderfully fascinating and eccentric actor he was. I was sorry to learn of Peter O’Toole’s death a couple of days ago. He was 81.

O’Toole “burst” onto the scene as a major film star at the age of 30, when he portrayed T.E. Lawrence in the blockbuster film, Lawrence of Arabia. That was in 1962. I saw the film on a U.S. military base in Germany when I was in high school. While I admired O’Toole’s acting, it was the character he portrayed who caught my imagination. I began reading whatever I could lay my hands on that told about the life and exploits of T.E. Lawrence (1888 – 1935). Lawrence was a British officer during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign and the Arab Revolt during World War I. His written accounts brought him to prominence. He was another eccentric Brit. The British seem to excel in producing eccentric characters, larger-than-life figures that fire young men’s imaginations. Or at least they did the imagination of this young man.

Once I’d exhausted my interest in T.E. Lawrence, somehow I turned to an earlier eccentric associated with the Arab world, the infinitely fascinating Richard Burton. Not the actor, I hasten to say. Rather the Victorian explorer, Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821 – 1890), who was an adventurer par excellence. He also was a writer and translator, known famously for his unexpurgated translation of One Thousand and One Nights, which challenged the Victorian mores of his day. My late wife was captivated by this particular work, and at some point in the 1970s I was able to secure for her a boxed, three-volume set of Burton’s translation in an edition from the 1930s.

O’Toole never played the Victorian eccentric on stage or screen, though he would have been well cast. On the other hand, he was a great friend of the other Richard Burton, with whom he co-starred in Becket. The two claimed to have been drunk throughout most of the filming.

Peter O’Toole (1932 – 2013) emerged as a film star in serious dramas of the 1960s: Becket(1964) and The Lion in Winter (1968), in addition to Lawrence—all three leading to Academy Award nominations. In all, he was nominated eight times and never won. In 2003 the Academy gave him an honorary award for his lifetime of work.

Though he was initially recognized for dramatic works, he also excelled at comedy—and as often on stage as on film. In the early 1980s, I was fortunate to see him in George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman at the Theatre Royal in London. What a treat! O’Toole naturally played Jack Tanner, the Don Juan character of the play. To see him work his magic on the boards from a seat midway in the stalls was sheer delight.

I suspect movie and theater buffs must all have their favorite recollections of Peter O’Toole. He is reported to have said, “I will not be a common man. I will stir the smooth sands of monotony.” He certainly did that.

Published on December 16, 2013 09:30

December 6, 2013

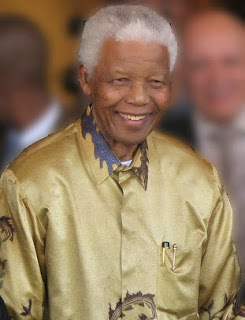

Out of Africa: Peace and More

The death this week of Nelson Mandela (1918 – 2013), the man who became the face of South Africa and a voice of peace for the world, set me pondering the huge effect that individuals with ties to the vast continent of Africa have had on American culture in every aspect. Mandela was influential as a leader of conscience. It is a role shared across fields of endeavor, whether politics, religion, the sciences, the arts, and so forth. I think of Desmond Tutu, the Anglican bishop, another South African whose voice has extended far beyond that nation and that continent. Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984; Mandela in 1993.

The death this week of Nelson Mandela (1918 – 2013), the man who became the face of South Africa and a voice of peace for the world, set me pondering the huge effect that individuals with ties to the vast continent of Africa have had on American culture in every aspect. Mandela was influential as a leader of conscience. It is a role shared across fields of endeavor, whether politics, religion, the sciences, the arts, and so forth. I think of Desmond Tutu, the Anglican bishop, another South African whose voice has extended far beyond that nation and that continent. Tutu won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984; Mandela in 1993.But I also think of Africa’s “cultural ambassadors” whose work has touched the world’s conscience, such as Grammy-winning singer Miriam Makeba (1932 – 2008), whose activism for civil rights earned her the nickname Mama Africa. I hear echoes of her voice and passion in the music of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, the all-male vocal group from South Africa that was brought to worldwide attention with their collaboration on Paul Simon’s 1986 album Graceland, some twenty-six years after the group’s formation. I also hear Makeba in the all-female a cappella African American group Sweet Honey in the Rock, which I had the pleasure of hearing live at a reception in Washington, D.C., about a decade ago.

From African to African American—a fraught transition in many ways. But how enriched our culture, and by turns world culture, has been by the many influential individuals and groups whose ancestors, for the most part, came to our shores unwillingly. These descendants of slaves and indentured servants might just as easily have turned their backs to the culture of their oppressors. Instead, they gave us their culture in every conceivable way, whether in the civil rights work of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929 – 1968, Nobel Peace Prize 1964), the poetry of Maya Angelou, the enduring jazz of Louis Armstrong (1901 – 1971), the photography of Gordon Parks (1912 – 2006), or the work of singer and actress Audra McDonald. The list goes on forever.

And at last we have an American president who identifies as black and traces distant roots to Africa. Barack Obama, another Nobel Peace Prize winner (2009), has faced an uphill battle, not only as an individual to seek the top political job in our nation, following 43 white predecessors, but also, and perhaps most significantly, to overcome our national legacy of racism—racism that is still all-too-alive among large segments of the population. Much of the political gridlock in contemporary times can be traced not merely to political differences but to the entrenched racism of rightwing America, however conservative politicos and pundits try to whitewash it.

African influences have enriched the collective life of the United States and the world in immeasurable ways. As I paused this week to reflect on the life of Nelson Mandela, I could not help but be overwhelmed by the recollection of many of the individuals coming out of Africa, whether historically or in the present day, who, in the words of Martin Luther King, “will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” More and more Americans are achieving this ideal viewpoint, but for some it is still a challenge. That means we all simply must work harder for a quality of human connectedness that transcends place and race.

Published on December 06, 2013 04:25

November 14, 2013

Cat's Condition

The recent Indiana University Theater production of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roofdid not disappoint, as I feared it would. I was concerned that it might pale against the memory of a London production some ten years ago that starred Brendan Frazer and Ned Beatty in the roles of Brick and Big Daddy. It did not. It was well acted and admirably staged.

The recent Indiana University Theater production of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roofdid not disappoint, as I feared it would. I was concerned that it might pale against the memory of a London production some ten years ago that starred Brendan Frazer and Ned Beatty in the roles of Brick and Big Daddy. It did not. It was well acted and admirably staged.What struck me instead was how commonplace and less fraught the two central dramatic themes—cancer and homosexuality—have become since the play was first performed in 1955. Mendacityis the catchword. Everyone is lying. Big Daddy has been lied to about his aggressive cancer, which will soon kill him. Brick is lying about his relationship with Skipper, a “pure” friendship that nowadays can only be seen as latently, if not overtly, gay. But Brick’s lie is as much for himself as for the family, and his own mendacity drives him to drink.

Tennessee Williams (1911-1963) achieved recognition as a playwright after years of toiling in obscurity. His star finally rose with the 1944 play, The Glass Menagerie. He was at his best in the 1940s and 1950s. Williams’ genre is Southern tragedy. His plots tend to be Shakespearean in character. In Cat the king is dying. Big Daddy’s plantation empire is at stake. Rival brothers and their rapacious wives have gathered for the end that everyone except the king knows is coming. Big Daddy has been kept in the dark by the family’s treacherous secrecy and his own self-delusion. Big Daddy is lying to himself as much as Brick is lying to himself about their respective conditions.

But the conditions have lost the punch they had half a century ago. Cancer, while potentially devastating, is no longer spoken of in whispers. In Cat it is regarded as an automatic death sentence, which it usually was in the 1950s. Similarly, Brick’s homosexuality, whether he ever acted on it or not, is a dirty secret, one that has driven him into alcoholism—and drove his “friend” Skipper to suicide. Of course, homophobia and guilt still drive people to suicide today; the cyberbullying and gay teen suicide statistics are appalling. But being gay—or having homosexual thoughts—are no longer discussed only in whispers. More than a dozen U.S. states and several counties allow gay marriage. The world has changed. Mendacity regarding cancer and homosexuality is no longer the norm, no longer the stuff of great drama.

Williams’ Cat is well crafted, a classic perhaps, but no longer contemporary. The larger issues of the dying king and the lies people tell to delude themselves and others are as timeless as they are in Shakespeare. But the twin vehicles of Williams’ drama—cancer and homosexuality—throw the play into the class of historical drama. They are horse-and-buggy themes in a hybrid electric era. That said, it is no less watchable. Cat still offers an evening of compelling drama.

Published on November 14, 2013 06:12