Donovan R. Walling's Blog, page 6

March 4, 2012

Scandalous Behavior

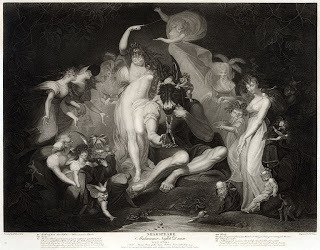

Two performances this past week called vividly to mind the perpetual theatrical theme of scandalous behavior. People behaving in ways contrary to accepted norms of society—usually in a sexual context—is a staple plot device of both comedy and tragedy. This week it was comedy, with scandalous behavior in the enchanted woods in Midsummer Night's Dream and scandalous behavior among the aristocracy in Der Rosenkavalier.

The Indiana University production of Shakespeare's enduring comedy, Midsummer Night's Dream, was set in a 1934 Hollywood movie studio. Oberon, the king of the fairies, swung in on a grapevine with a finer set of chiseled abs than Johnny Weissmuller could ever boast of. One couldn't help being disappointed when he later appeared fully clothed. Three sets of lovers—intermingling while enchanted—essentially behave both badly and scandalously (a fine distinction): Oberon and his queen Titania (whom Oberon enchants and causes to fall in love with an ass), Hermia and Demetrius (whom Hermia does not love, to the consternation of her father Egeus), and Lysander and Helena (who are thrown together mistakenly by Oberon's jester Puck).

It's a confusing plot, of course, following the standard devises of disguises, enchantments, and mistaken identities, all familiar in Shakespearean comedies. Ultimately, it all boils down to love and sex, generally of a scandalous nature. In the end Lysander and Hermia unite, true love winning out. Demetrius claims Helena as a newly rediscovered true love, and Oberon reunites happily with his queen, Titania. All's well that ends well—but that's another play.

Der Rosenkavalier, by Richard Strauss, was a highlight of the Indiana University opera season. Those unfamiliar with the opera might well have wondered at two women in bed at the opening curtain. One woman, however, is a man—well, a boy. The role of Octavian traditionally is played by a mezzo soprano, which even though Octavian is supposed to be seventeen is a stretch. But Strauss was inordinately fond of sopranos, and so he managed to populate this opera with several.

An openly lesbian plot would have been too avant garde in 1911, when the opera premiered in Dresden. (A little girl-on-girl apparently went down well.) Opening with the much older (and of course married) Marschallin, Princess Marie Thérèse, cavorting in bed with her seventeen-year-old lover was scandalous behavior enough. There's bad behavior, though scandalous as well, from the lecherous Baron Ochs, who schemes to marry the nubile, and much younger, Sophie. The Baron avers that scandalous behavior is what sets an aristocrat apart from the common herd.

When the lovestruck Octavian is reluctantly set free by the Marschallin, with the comment that he'll turn to someone younger sooner or later, he promptly does. With Sophie and Octavian it's love at first sight. A good deal of comedic mischief follows, involving Octavian disguised as a servant girl—a girl playing a boy playing a girl, shades of Victor Victoria! Octavian's servant girl persona, "Mariandell," entices Ochs to an illicit rendezvous, where the Baron is exposed as the rogue he is. With the Marschallin's blessing, and Sophie's father's, Octavian and Sophie are united in the end.

Ah, scandalous behavior! It's almost as good on stage as it is in the newspapers.

February 3, 2012

When “Live” Isn’t Quite

Technological wizardry has blurred the distinction between “live,” meaning right in front of you that very moment, and “live,” meaning at that moment but somewhere else. The range of examples is ever expanding.

The other day two friends spent FaceTime together, conversing “live” for several minutes. One was in Indiana, the other in Indonesia. FaceTime is the Apple app that allows users to make video calls. Skype is a similar service for audio or video calls through computer linkups.

Go from personal to performance and one can find any number of “live” events at the local movie theater, where audience members can watch, for instance, a Metropolitan Opera performance—almost but not quite—as though they were sitting in the hall at Lincoln Center—with ticket prices higher than normal for a movie but less than it would cost to be there in New York City.

When school budgets are too constrained to permit field trips, I’ve often advocated “virtual field trips,” taking students to places through the computer that they might never be able to visit in person. For example, students studying art or language might virtually “tour” the Louvre Museum in Paris. The museum offers a range of “thematic trails,” tours that can be taken online or in person. And the website provides its content in English, French, Chinese, and Japanese.

The difference between a virtual field trip and a virtual “live” event is synchronicity. That is, two live events are linked in real time. The opera performance is live in New York City. The audiences, plural, are live both there and in movie theaters where the live performance is being synchronously transmitted.

As this technology becomes ever more commonplace, its permutations are endless. A recent example brought to my attention was a retail music store opening in Fort Wayne, Indiana, at which a Yamaha piano was played remotely by pianist Mike Garson, who played an electronically linked instrument in the Yamaha corporate offices in Los Angeles. (See video.) In this instance, store visitors could witness a “live” performance in the same room as the instrument, while the performer was somewhere else.

Blurring the definition of “live” is a facet of technology that has been woven increasingly into the fabric of our lives, at least since Alexander Graham Bell made the first telephone call. At this point, one can only wonder, What next? And, more to the point, when will “live” cease to have any real meaning?

When "Live" Isn't Quite

Technological wizardry has blurred the distinction between "live," meaning right in front of you that very moment, and "live," meaning at that moment but somewhere else. The range of examples is ever expanding.

The other day two friends spent FaceTime together, conversing "live" for several minutes. One was in Indiana, the other in Indonesia. FaceTime is the Apple app that allows users to make video calls. Skype is a similar service for audio or video calls through computer linkups.

Go from personal to performance and one can find any number of "live" events at the local movie theater, where audience members can watch, for instance, a Metropolitan Opera performance—almost but not quite—as though they were sitting in the hall at Lincoln Center—with ticket prices higher than normal for a movie but less than it would cost to be there in New York City.

When school budgets are too constrained to permit field trips, I've often advocated "virtual field trips," taking students to places through the computer that they might never be able to visit in person. For example, students studying art or language might virtually "tour" the Louvre Museum in Paris. The museum offers a range of "thematic trails," tours that can be taken online or in person. And the website provides its content in English, French, Chinese, and Japanese.

The difference between a virtual field trip and a virtual "live" event is synchronicity. That is, two live events are linked in real time. The opera performance is live in New York City. The audiences, plural, are live both there and in movie theaters where the live performance is being synchronously transmitted.

As this technology becomes ever more commonplace, its permutations are endless. A recent example brought to my attention was a retail music store opening in Fort Wayne, Indiana, at which a Yamaha piano was played remotely by pianist Mike Garson, who played an electronically linked instrument in the Yamaha corporate offices in Los Angeles. (See video.) In this instance, store visitors could witness a "live" performance in the same room as the instrument, while the performer was somewhere else.

Blurring the definition of "live" is a facet of technology that has been woven increasingly into the fabric of our lives, at least since Alexander Graham Bell made the first telephone call. At this point, one can only wonder, What next? And, more to the point, when will "live" cease to have any real meaning?

January 25, 2012

Resilience Through Music

Recently I enjoyed a performance by the West Point Chamber Winds ensemble of the West Point Band. Having been reared in an Army family, I confess to a predisposition to like military music groups. The West Point Band is the oldest of the Army bands, founded in 1817. The West Point Chamber Winds ensemble of crisply uniformed, active-duty soldiers and superb musicians did not disappoint.

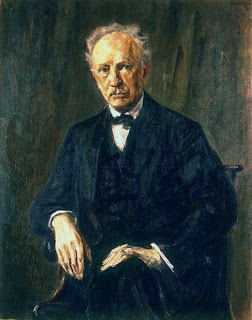

Their choice of two compositions by Richard Strauss (in a 1918 portrait by Max Liebermann, right) to bookend the recital was intriguing. The first was "Serenade in E-Flat Major, Op. 7," which Strauss composed as a seventeen-year-old in 1881. The last was the less-often played "Sonatina No. 1 in F," from 1943, only a few years before Strauss's death in 1949 at age 85.

Richard Strauss (June 11, 1864 – September 8, 1949) began composing very young. Indeed, he was six when he wrote a Christmas carol and a polka. His father was Franz Strauss, a horn player. The elder Strauss, having lost his wife and two children to a cholera epidemic in 1853, remarried. His new wife, Josepha Pschorr, was the daughter of a wealthy Munich brewer and soon gave him a son, Richard, who would become the preeminent composer of the late Romantic period.

"Serenade in E-Flat Major" or "Serenade for 13 Winds" was composed about the time Richard Strauss entered the University of Munich. It was first performed in Dresden on November 27, 1882. But while this early work illustrates youthful brilliance, it is the later composition, "Sonatina No. 1 in F," which shows Strauss's resilience.

Strauss was 68 when the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in 1933. Although Strauss avoided joining the party, Adolf Hiltler nevertheless determined to use Strauss and his work to promote German art and culture. Strauss went along, even becoming (though without his prior consent) president of the Reichsmusikkammer, the State Music Bureau. (He was later dismissed after a critical letter he had written surfaced.) Strauss was criticized for his involvement with the Nazis, but he felt it was necessary to protect his Jewish daughter-in-law and grandchildren, for Strauss's only son, Franz, had married a Jewish woman, Alice von Grab; and the couple had two sons.

This was the backdrop against which Richard Strauss composed "Sonatina No. 1 in F." in 1943, as the long Nazi era and the years of war were grinding on and as he was approaching 80 and ill (consequently the composer's subtitle, "from an invalid's workshop"). And yet, though the composition has been called nostalgic, it is full of optimism, which propels the melody in the higher notes over an undercurrent of, at times, rumbling low notes, almost as if Strauss is choosing to float above the rubble of war. In fact, Strauss would be much affected in October the same year, following the bombing of the National Theater in Munich, which Strauss wrote to his friend and biographer, Willi Schuh, was "the holy site of the first Tristan and Meistersinger performances, where I heard Freischütz for the first time 73 years ago, where my good father sat in the orchestra for 49 years at the first horn desk…."

One cannot help but believe that music provided Strauss with the resilience to persevere, and we the listening public are richer for it.

The West Point Chamber Winds recital was the 458th program of the 2011-12 season at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music on January 24, 2012. This spring the IU Opera Theater will present Strauss's Der Rosenkavalier. It should be a treat not to be missed.

January 23, 2012

An American Fin de Siècle?

There are any number of good reasons to watch the popular PBS series, "Downton Abbey," not least for the simple pleasure of enjoying Maggie Smith's portrayal as the Dowager Countess of Grantham (photo). The Edwardian tale offers viewers a fictional, but largely accurate, glimpse into the end of an era, that age when Britain's landed aristocracy ruled not only the nation but also the empire and therefore much of the world.

The upstairs/downstairs gap between wealth and poverty, power and subservience, is being turned on its head by World War I during the drama's second season—and it's probably a good thing. The war, abetted by the advent of the Industrial Age, accomplished in Britain a socioeconomic transition that was achieved elsewhere by revolutions. The disparity between rich and poor had spurred Britain's near neighbor to the French Revolution only slightly more than a century earlier. And the Russian revolution was fermenting during the First World War as Britain looked on, and worried.

The fin de siècle for the British aristocracy was cinched by the rise of a corporate-industrial elite. In recent years Britain has again become keenly aware of a growing gap between wealth and poverty, particularly in light of recent global economic woes. As I write this the New York Times has reported on the "rising outcry over executive pay" by lower-wage workers (and the unemployed), as reflected by the Occupy London movement.

In the United States, as conservatives have pushed this country increasing away from democracy toward corporate oligarchy, the gap between the moneyed elites and the rest of us has grown alarmingly. Between 1997 and 2007 the top one percent of Americans saw their incomes rise 275 percent, while the bottom fifth gained only 20 percent. The Huffington Post, reporting on a historical study, recently headlined: "U.S. Income Inequality Higher Than Roman Empire's Levels."

Such disparity, in concert with the generally depressed economic climate, in part, gave rise to the Occupy Wall Street movement that spread across the nation and internationally during 2011. While the Occupy movement seems to have had its fifteen minutes in the spotlight, it is by no means defunct. Nor are the feelings of outrage that gave rise to it less intense. Economists such as Jared Bernstein and Paul Krugman have termed America's income gap "unsustainable" and "incompatible" with democracy.

One wonders, given this dynamic, whether the United States is heading for a fin de siècle for its corporate artistocracy. And how will the transition occur? Will television viewers a century from now be watching a mirror version of "Downton Abbey," perhaps called by some fictional version of "Trump Tower"? That the tower must fall is assured. The question is how. And will the nation fall with it or survive, and in what form?

December 14, 2011

’Tis the Season for Red, Green…and Blue

Maybe it’s the contrarian in me, but seasons of forced jollity tend to evoke the opposite emotions of sadness and loss. I know I’m not alone. Blue Christmas is a universal phenomenon.

My partner and I were reminded by the season that for the past four years we have lost family members during the holidays: a brother each, a mother, and an ex-brother-in-law. More than a decade ago my father died on Christmas Eve. Loss, though purely coincidental with the festive season, is nonetheless more keenly felt when all about you is supposed to be joyful.

Music is the emotional marker, and everyone has a selection of popular sad-song favorites this time of year. I’ll limit myself to three.

The oldest is “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” first recorded by Bing Crosby in 1943. The lyric represents a letter home, written by a serviceman posted overseas during World War II. “I’ll be home for Christmas,” the lyric goes, “if only in my dreams.” Bing’s rendition was a top-ten hit, and the song seems to have been recorded by a new artist or two every year. It probably resonates with me because my father was a serviceman, posted overseas during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. Most military families have endured missed Christmases. And because this country is perpetually at war, it seems, there's no end in sight.

“Blue Christmas,” written by Billy Hayes and Jay W. Johnson, was initially recorded by Doyle O’Dell in 1948 but more memorably by Ernest Tubb a little later. Tubb’s rendition occupied the #1 spot on Billboard magazine’s Most-Played Juke Box (Country and Western) Records for the first week of January in 1950. However, the most popular version came nearly a decade and a half later, when Elvis Presley recorded it for the album, Blue Christmas, which was released in November 1964. The album was among a cluster of “comeback” recordings during the years following Elvis’s stint in the military from March 24, 1958, to March 2, 1960, when he was discharged with the rank of sergeant.

Interestingly, Presley was stationed in Friedburg, Germany, beginning October 1 of 1958. Our family was posted to Butzbach, Germany, that year; I was ten years old when Mom, my brother, my sister, and I arrived to join Dad in what was then West Germany on December 14. While Elvis was in Germany, he met fourteen-year-old Priscilla Beaulieu, whom he would marry after a seven-and-a-half-year courtship.

The last of my three is “Hard Candy Christmas,” written by Carol Hall for the musical The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. Who’d have thought that a song sung by the evicted prostitutes of a Texas brothel would become a sad Christmas standard? In the movie version Dolly Parton played the madame and released her version of the song in October 1982. It climbed to #8 on the U.S. country singles chart. The film adaptation also featured some songs added by Dolly, including “I Will Always Love You,” which later became a hit for Whitney Houston, although I’ve always favored Dolly’s rendition.

Others can add their sad favorites for this season, and I could mention a few more. But three are sufficient.

'Tis the Season for Red, Green…and Blue

Maybe it's the contrarian in me, but seasons of forced jollity tend to evoke the opposite emotions of sadness and loss. I know I'm not alone. Blue Christmas is a universal phenomenon.

My partner and I were reminded by the season that for the past four years we have lost family members during the holidays: a brother each, a mother, and an ex-brother-in-law. More than a decade ago my father died on Christmas Eve. Loss, though purely coincidental with the festive season, is nonetheless more keenly felt when all about you is supposed to be joyful.

Music is the emotional marker, and everyone has a selection of popular sad-song favorites this time of year. I'll limit myself to three.

The oldest is "I'll Be Home for Christmas," first recorded by Bing Crosby in 1943. The lyric represents a letter home, written by a serviceman posted overseas during World War II. "I'll be home for Christmas," the lyric goes, "if only in my dreams." Bing's rendition was a top-ten hit, and the song seems to have been recorded by a new artist or two every year. It probably resonates with me because my father was a serviceman, posted overseas during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. Most military families have endured missed Christmases. And because this country is perpetually at war, it seems, there's no end in sight.

"Blue Christmas," written by Billy Hayes and Jay W. Johnson, was initially recorded by Doyle O'Dell in 1948 but more memorably by Ernest Tubb a little later. Tubb's rendition occupied the #1 spot on Billboard magazine's Most-Played Juke Box (Country and Western) Records for the first week of January in 1950. However, the most popular version came nearly a decade and a half later, when Elvis Presley recorded it for the album, Blue Christmas, which was released in November 1964. The album was among a cluster of "comeback" recordings during the years following Elvis's stint in the military from March 24, 1958, to March 2, 1960, when he was discharged with the rank of sergeant.

Interestingly, Presley was stationed in Friedburg, Germany, beginning October 1 of 1958. Our family was posted to Butzbach, Germany, that year; I was ten years old when Mom, my brother, my sister, and I arrived to join Dad in what was then West Germany on December 14. While Elvis was in Germany, he met fourteen-year-old Priscilla Beaulieu, whom he would marry after a seven-and-a-half-year courtship.

The last of my three is "Hard Candy Christmas," written by Carol Hall for the musical The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. Who'd have thought that a song sung by the evicted prostitutes of a Texas brothel would become a sad Christmas standard? In the movie version Dolly Parton played the madame and released her version of the song in October 1982. It climbed to #8 on the U.S. country singles chart. The film adaptation also featured some songs added by Dolly, including "I Will Always Love You," which later became a hit for Whitney Houston, although I've always favored Dolly's rendition.

Others can add their sad favorites for this season, and I could mention a few more. But three are sufficient.

December 2, 2011

Holiday Movie, Anyone?

Everyone has some favorite holiday movies, so why shouldn't I trot out my Top Five list? The season is made for nostalgia—for good or ill—and so I find that most of my favorites are, as they say, vintage. Here goes:

1. Miracle on 34th Street may be my all-time favorite. I'm talking about the 1947 black-and-white film that stars Edmund Gwen (as Kris Kringle, shown), Maureen O'Hara, John Payne, and a very young Natalie Wood. The remake pales by comparison. The original was one of the first films to be "colorized"—a crime against art if there ever was one.

2. The Lemon Drop Kid, 1951, gets a vote because Bob Hope and Marilyn Maxwell introduced my favorite Christmas carol, "Silver Bells," in it. Holiday Inn, the 1942 Bing Crosby-Fred Astaire vehicle that introduced "White Christmas," is a runner-up and better, in my view, than the movie with which it's often confused, White Christmas, a 1954 film that starred Bing Crosby, Danny Kaye, Rosemary Clooney, and Vera Ellen.

3. Charles Dickens' novella, A Christmas Carol, has been translated to film repeatedly, apparently so that every generation can have its own. Well, for me, it's the 1951 version, starring Alistair Sim. Another black-and-white classic.

4. The 1944 Judy Garland film, Meet Me in St. Louis, isn't a holiday movie per se, but Garland did introduce "Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas," which has become a holiday standard. Another non-holiday film with a favorite Christmas song is Mame, in which Lucille Ball sang "We Need a Little Christmas," though the film was a less successful vehicle than the original stage musical, which starred Angela Lansbury.

5. Tim Burton's The Nightmare Before Christmas, 1993, features such haunting music paired with innovative animation that I cannot help but enjoy it time and again. If it were a feature film, I'd also throw in the television favorite, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! This Dr. Seuss book was made into an animated film for TV in 1966, starring Boris Karloff as the narrator and the voice of the Grinch. I watch it every year and it's always magical.

Granted, I fudged the list to mention more than five films. There are many others that make popular lists that I haven't included. They simply don't resonate with me; they may with you. Winter weather makes this time of year perfect to cuddle up with someone you love, share a hot chocolate, and watch a holiday favorite. That's what I plan to do.

November 14, 2011

Walking

In his essay, "Walking," Henry David Thoreau writes:

I think that I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend four hours a day…sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements…. I am reminded that the mechanics and shopkeepers stay in their shops not only all the forenoon, but all the afternoon, too…. I think that they deserve some credit for not having all committed suicide long ago.

Of course, most of us are like those mechanics and shopkeepers. We don't have the luxury of spending our days walking away our cares in woodland rambles. But Thoreau's point should not be lost for our lack of time. There is much to be gained from walking—physically, intellectually, and emotionally.

Thoreau walked away from civilization, making much of avoiding towns and settlements. I have spent many pleasant hours walking in woods in all seasons. During twenty years in Wisconsin, the Kettle Moraine State Forest was a frequent destination, particularly in winter when a light snow had salted among the leafless trees and evergreens.

But I would equally advocate walking in more civilized environs. I am a town walker, a city saunterer.

Unlike driving or even bicycling, walking allows the solo pedestrian opportunities to observe his or her fellow inhabitants, both the two-legged and the four-legged varieties. Not long ago, for instance, I rounded a corner in the early-morning semi-darkness only to find that a deer and I were mutually surprised by one another's presence.

Anyone who enjoys architecture—domestic or commercial—gardens, trees, clouds, indeed whatever the world has to offer can enjoy a walk. And even daily walks in the same general area produce a variety of sights, sounds, and smells. Plus, each day the walker carries different thoughts. Walking is an effective way to stimulate the subconscious to tackle old problems and come up with new ideas.

Having a destination, even if it's only a coffee shop or the local library, helps motivate my walks. But, in the end, they are as Thoreau describes them: "Our expeditions are but tours, and come round again at evening to the old hearth-side from which we set out."

October 17, 2011

Street Theater, Now and Then

Public protests are a type of street theater, scripted or impromptu to varying degrees. It's been interesting to watch the Occupy Wall Street protest "go viral" and spread to other cities and towns. Largely a libertarian, leftist protest, with smatterings of sympathy across the political spectrum, it may or may not effectively awaken the populous to the ever-increasing threat that America, since the late-twentieth-century assault on the middle class began, is becoming a pseudo-democratic corporate oligarchy. From Reagonomics onward, the "99%" have been losing out to the "1%," and it's uncertain whether the Occupy movement—or the libertarian, rightwing Tea Party movement, for that matter—will do more than riffle the water in the stream of history.

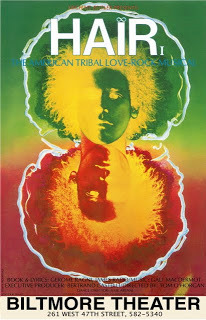

A recent Indiana University production of the 1968 Rado-Ragni-McDermot antiwar, sexual revolution era, rock musical, Hair, evoked another age of public protest as theater. The students onstage and peppered throughout the audience undoubtedly viewed the show as ancient history. The rock score may have resonated with some, making the production perhaps a little more relevant that other antiwar stage vehicles, such as Bertolt Brecht's World War II era Mother Courage and Her Children or Aristophenes' Lysistrata, which played in Athens about 411 BCE. But for those in the audience who, like me, were in college in 1968, Hair brought back memories of public protests far more strident, wide spread, and ultimately effective.

After all, America in the Sixties was embroiled in the Vietnam War, a conflict that many saw as unnecessary (at least in terms of U.S. involvement) and unwinnable—which, in fact, we were not winning. Moreover, America was conscripting thousands of young men to fight in this war, and many of them would be killed doing so. Death tolls were rising, and grizzly scenes of battle played nightly on televisions everywhere. Still, Hair today might seem to be merely a quaint memoir of a bygone era. This is particularly the case, given most American's blasé response to the more recent Bush era, knee-jerk response to the terrorist attacks of 2001: invading Iraq as part of a so-called War on Terror. No one would argue that the horrific acts of terrorism deserved a response. The war in Iraq simply was the wrong one. But there have been no wide-spread public protests, certainly nothing on the scale of the antiwar protests of the Vietnam era.

Hair is a reminder of the power of public protest—theater of the people with a political purpose. The War on Terror and its domestic counterpart, an economic war on the middle and lower classes, have given us the worst recession since the Great Depression. The Occupy movement may spur a broader awakening to the corporate takeover of American democracy—or not. Time will tell. For the moment, it's street theater worth watching. If it changes the public conversation about America's increasing disparity between rich and poor, haves and have nots, then it may one day be worth viewing in retrospect as well.