Donovan R. Walling's Blog

May 10, 2017

Obituary

Donovan R. Walling, born January 9, 1948, in Kansas City, Missouri, died May 5, 2017. He was the son of Donovan Ernest and Dorothy (nee Goyette) Walling. A lifelong educator, Walling taught school in Wisconsin and Germany, was a curriculum administrator in Wisconsin and Indiana, and served as director of publications for the education association Phi Delta Kappa, retiring in 2006. He continued to work as a writer and editorial consultant in retirement, and was a senior consultant for the Center for Civic Education. Walling was the author or editor of numerous books in education and also wrote fiction and poetry. He was preceded in death by his wife Diana (nee Eveland) in 1991. He is survived by his husband Sam Troxal; his children, Katherine, Donovan David, and Alexander; and several grandchildren.

In light of Donovan’s lifelong commitment to education, his family requests memorial contributions be made to the Walling-Troxal Endowed Scholarship Fund at First United Church. A celebration of his life will be held Saturday, June 16 at 7pm at First United Church, 2420 E Third Street in Bloomington, Indiana.

In light of Donovan’s lifelong commitment to education, his family requests memorial contributions be made to the Walling-Troxal Endowed Scholarship Fund at First United Church. A celebration of his life will be held Saturday, June 16 at 7pm at First United Church, 2420 E Third Street in Bloomington, Indiana.

Published on May 10, 2017 08:46

January 17, 2017

Scholder's Expressionist Americans

The American Indian

The American IndianOil on linen, 1970A quote that I noticed on Martin Luther King Jr. Day this week, juxtaposed with Inauguration Day coming at the end of the week, set me thinking about our nation’s first true citizens. King said, “Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race.” My train of thought barreled on, eventually arriving at a Native American artist whom I have long admired: Fritz Scholder.

Scholder (October 6, 1937 – February 10, 2005), who was one-quarter Luiseño, a California Mission tribe, was an Abstract Expressionist. The imagery in his paintings invariably drew on Native American themes and individuals. Several paintings, like the one shown above, were of native figures draped in the American flag.

King, to expand the quote, went on to say, “Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shore, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society. From the sixteenth century forward, blood flowed in battles over racial supremacy. We are perhaps the only nation which tried as a matter of national policy to wipe out its indigenous population. Moreover, we elevated that tragic experience into a noble crusade. Indeed, even today we have not permitted ourselves to reject or feel remorse for this shameful episode. Our literature, our films, our drama, our folklore all exalt it. Our children are still taught to respect the violence which reduced a red-skinned people of an earlier culture into a few fragmented groups herded into impoverished reservations.” King was speaking half a century ago, but his remarks are still pertinent.

Scholder tapped all of this history, weaving it into his extravagantly colorful paintings. I discovered Scholder’s work when I was attending college as an undergraduate art major in the late 1960s. Since that time, whenever I have visited a museum, I’ve always kept an eye peeled for a Scholder painting. Occasionally, though far too seldom, I have been rewarded. Sometime in the late 1970s, on a winter trip to Phoenix, Arizona, I wandered into a gallery that handled Scholder’s work. It was a spellbinding moment, to be surrounded, literally, by his paintings. The images ranged from fierce to whimsical. It was difficult to drag myself away.

Fritz Scholder is represented in numerous museums and galleries. Perhaps nearest my own location in southern Indiana, visitors to the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis can enjoy one of his works. Scholder’s paintings are worth contemplating, both from the standpoint of artistic expression and as a reflection of the interwoven themes of Native American history and the evolving place of Native Americans, minority individuals, and immigrants—all “othered” too often, instead of accepted as the true warp and woof of our national fabric.

With a fraught Inauguration Day approaching this week, such contemplation is timely. If you can’t find a Scholder painting in a nearby museum, google his name and explore the images online. I guarantee a rich visual experience.

Published on January 17, 2017 08:09

October 4, 2016

Franckaphilia

That was the title of a faculty recital I attended on a recent evening.

César FranckFully, it was “Franckaphilia: The Complete Organ Works of César Franck – Part I: From Palace to Paradise,” performed by Janette Fishell, IU Jacobs School of Music Organ Department Chair. She performed in Auer Hall on the magnificent and relatively new (dedicated in 2010) Fisk organ, named the Maidee H. and Jackson A. Seward Organ. A Part II recital has been scheduled for January 2017.

César FranckFully, it was “Franckaphilia: The Complete Organ Works of César Franck – Part I: From Palace to Paradise,” performed by Janette Fishell, IU Jacobs School of Music Organ Department Chair. She performed in Auer Hall on the magnificent and relatively new (dedicated in 2010) Fisk organ, named the Maidee H. and Jackson A. Seward Organ. A Part II recital has been scheduled for January 2017.Born in Liège, in what is now Belgium, César Franck (1822 – 1890) spent his adult life in Paris working as a pianist, organist, and composer. His work is typical of late Romantic musical compositions, but very enjoyable even if one isn’t predisposed to the Romantic period. This recital was composed of two sections. The first was “Trois pièces: No. 1 Fantaisie in A Major, No. 2 Cantabile, No. 3 Pièce héroïque,” followed, after a brief pause, by “Trois chorals: No. 1 in E Major, No. 2 in B Minor, No. 3 in A Minor.” Of all of repertoire, my favorite, and generally a crowd-pleaser, was the truly heroic, even bombastic, “Pièce héroïque.”

Fisk Organ in Auer Hall

Fisk Organ in Auer HallIU Jacobs School of MusicI have been told that the Auer Hall organ is particularly well suited to Romantic music. I wouldn’t know. I have enjoyed a number of recitals and concerts there, including the evening previous to this concert, when a young Mexican harpist of our acquaintance played his senior recital there. It’s a wonderful, contemporary, mid-size (400-seat) concert hall—a fine facility in a very fine school of music.

Franck himself was associated with a fine organ. In 1858 he became the organist at Sainte-Clotilde, a basilica church on the Rue Las Cases in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés area of Paris, and kept that position for the rest of his life. A year later the church acquired its famous Aristide Cavaillé-Coll organ, played by Franck and a number of later well-known composers. Franck subsequently became a French national and in 1872 was appointed to a professorship at the Paris Conservatoire.

Who knows whether I’ll manage to take in Part II of Franckaphilia, but if it happens I’m sure it will be equally enjoyable.

Published on October 04, 2016 16:47

August 10, 2016

Political Theater of the Absurd

P.T. Barnum portrayed as a

P.T. Barnum portrayed as a"Hum-Bug": a cartoon by H. L. Stephens (1851)Let’s be honest: Political campaigns often are as much about entertainment as serious stumping, regardless of party. At least in the beginning. At the start of the season candidate Donald Trump, now widely considered a fatal mistake for and by the Republican Party, could be compared to P.T. Barnum. Showman extraordinaire, Barnum (1810-1891) was America’s penultimate purveyor of humbug during the second half of the 19th century. “I am a showman by profession...and all the gilding shall make nothing else of me,” he said. Barnum also made a brief, unsuccessful foray into politics. He was a fitting model for Trump.

In the beginning Trump was a P.T. Barnum for our time. He might as well have adopted Barnum’s famous (though erroneously attributed) maxim: “There’s a sucker born every minute.” And the suckers flocked to him. No matter how outrageous his rhetoric, Trump’s adherents cheered.

But a gradual metamorphosis took place. Trump ceased to be funny. He became vicious. He attacked persons of color, immigrants, women, military veterans, the disabled, Muslims and Mexicans, even crying babies. He displayed a shocking disregard for the Constitution, law, and basic civility. Suddenly comparing Trump to Hitler, once regarded as political hyperbole, took on an air of prescience. The Barnum for our time shed his comedic cocoon to reveal a xenophobic, homophobic, racist, misogynistic, duplicitous proto-fascist, whose key supporters aligned themselves with the KKK and other white supremacist groups.

One often wonders, when watching Theater of the Absurd, where the line runs between reality and fantasy. It’s the theatrical equivalent of surrealism. Why are those clocks melting? Could clocks melt in real life?

We wait for Trump to say, “Just kidding! Surely you weren’t taking me serious.” But he does indeed seem to be serious. Thankfully many of the saner members of his own party have awakened to the imminent and very real danger of a Trump presidency and are turning against him. Sadly, even when the November election rings down the curtain on this absurd political theater, as it must, America will still have to deal with those in his audience who stayed to stand and cheer.

Published on August 10, 2016 07:18

April 24, 2016

A Tale of Two Sidneys

Sidney Bechet at Jimmy Ryan's Club

Sidney Bechet at Jimmy Ryan's Clubin New York City, 1947

Sidney Chambers, the troubled vicar of Grantchester in the PBS Mystery series that bears the name of this actual Cambridgeshire village, is fond of jazz music. So every now and then when Sidney is in a reflective mood, viewers are treated to a few snatches, which often happily feature the unmistakable trembling soprano sax tones of the incomparable Sidney Bechet.

I cannot recall when I discovered Bechet; it seems as though his special sound has always resided at least at the edge of memory whenever I’m not actually listening to one of his recordings.

The improbably handsome actor James Norton portrays the 30-something Anglican priest, a Cambridge graduate and former Scots Guards officer assigned to pastor Grantchester. But Sidney Chambers is hardly a simple country vicar, as the plots of these stories invariably revolve around the complex Reverend Chambers’ involvement in some crime or other. Bechet’s alternatingly poignant and playful sound complements the often fraught character of Sidney Chambers.

The series is set in the 1950s. When Sidney spins a Bechet LP on his turntable, lights up a cigarette, and leans back in his study chair with a tumbler of amber liquor, he listens to the jazz artist in his prime. New Orleans-born Sidney Bechet (1897-1959) was largely self-taught and was recognized fairly early in his career as perhaps the first notable jazz saxophonist, although he played several instruments.

Bechet played mainly clarinet professionally in New Orleans and elsewhere during the Teens and then about 1920 traveled to London, where he discovered the straight soprano sax. The instrument would be used to produce his signature sound. Critics called it “emotional,” “reckless,” and “large.” His sound featured a broad vibrato, a technique common to some New Orleans clarinetists at the time.

Bechet’s reckless, erratic behavior was career limiting. For example, he was imprisoned in London for several days in 1922, having been convicted of assaulting a woman, and was subsequently deported back to the United States. Consequently Bechet did not truly rise to fame until the 1940s. After performing at the Paris Jazz Festival, he moved permanently to France in 1950, and his popularity surged there. The next year he married Elisabeth Ziegler in Antibes.

Sadly, Sidney Bechet died of lung cancer in Garches, near Paris, on May 14, 1959, his sixty-second birthday. Fortunately his recordings live on so that we, like Grantchester’s other Sidney, Reverend Chambers, can still get lost in the trembling tones of Bechet’s sax. I recommend “Petite Fleur,” Bechet’s own composition, which he recorded In 1952: http://youtu.be/wMwckuWpxDs. You will fall in love with the sound.

Published on April 24, 2016 13:06

March 26, 2016

Small-Screen Mysteries

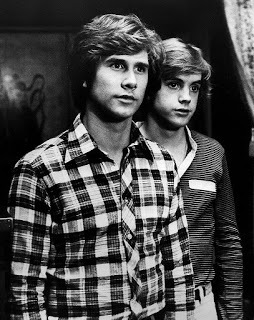

Parker Stevenson(as Frank Hardy) and

Parker Stevenson(as Frank Hardy) and Shaun Cassidy (as Joe Hardy) from

the Hardy Boy Mysteries of the 1970s.

Rewatching some of the early episodes of the PBS television series of Agatha Christie’s mysteries featuring Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, so aptly portrayed by the incomparable David Suchet, set me thinking about other small-screen adaptations that I have enjoyed seeing as thoroughly as I liked reading the original books and short stories.

Like many of my generation—and before and after—my love of mystery novels began during my preteen years in the 1950s, when I discovered the Hardy Boys. The books were “factory” novels, like the Nancy Drew books, written by a number of ghostwriters under the collective pseudonym Franklin W. Dixon. Teenage detectives Frank and Joe Hardy enjoyed a run on television in the late 1970s, played by teen heartthrobs Shaun Cassidy and Parker Stevenson.

The decade of the 1970s also saw a series of television programs based on the Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries by Dorothy L. Sayers, a contemporary of Agatha Christie. The tongue-in-cheek aristocratic amateur detective of the title was played by Ian Carmichael, my favorite among the Lord Peter portrayers.

And, of course, the next decade bore witness to the start of a long series of television adaptations of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novels and short stories, with Jeremy Brett as the eccentric detective. Brett became the quintessential Holmes, just as Suchet has become the definitive Poirot, both actors filming the majority of their respective canons. At least for their—and my—generation.

Great mysteries will always find new adaptations for new generations of enthusiasts. And then there are the mystery novels being written now that will find their way to the small screen to the delight of new audiences of mystery addicts. I could certainly suggest a few characters that I’d like to see. One would be Maisie Dobbs, the World War I nurse turned 1920s private detective, from the well-crafted series by Jacqueline Winspear.

Or what about the Roman Empire era “finder” Marcus Didius Falco, who stars in the wonderfully well-researched historical mysteries by Lindsey Davis? And then there’s Diane Mott Davidson’s caterer-cum-snoop Goldie Schulz and Greg Herren’s gay New Orleans-based New Age detective Scotty Bradley. Well, the list could go on and on. I am addicted to mysteries after all. Who are your favs?

Published on March 26, 2016 15:15

February 28, 2016

Poetry

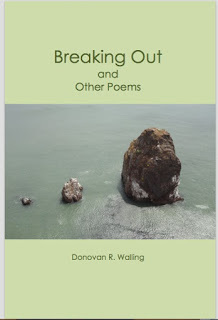

My interest in writing poetry began in high school and continued into college, although nothing I produced then was particularly worth reading. After college, in the 1970s, I wrote poems with greater intent and even published a few. But after that decade other interests, activities, and life in general made for about a thirty-year hiatus. I didn’t take up writing poems with any real passion again until after I retired in 2006.

My interest in writing poetry began in high school and continued into college, although nothing I produced then was particularly worth reading. After college, in the 1970s, I wrote poems with greater intent and even published a few. But after that decade other interests, activities, and life in general made for about a thirty-year hiatus. I didn’t take up writing poems with any real passion again until after I retired in 2006.Nowadays I write for my own pleasure, and I share my work with family and friends. My poems tend to be either autobiographical or responsive to nature—or both. I don’t consider myself a nature poet, but I have always responded to the passing seasons, flora and fauna, and weather phenomena. Perhaps because I also work in the visual arts, mainly as a painter, I try to create visual images with words. I have persisted in a lifelong fascination with impressionistic and expressionistic free verse, inspired by the likes of Sylvia Plath, Theodore Roethke, and many, many other Modern poets. If there is one thread, however slender, that unites at least some of my poems now, it is reflection on aging, keenly felt in particular since my cancer diagnosis in April 2015.

Is writing poems a form of therapy? Certainly. What artistic expression is not? But writing, at least for me, is always more than that. It is the creation of art, which in itself is intensely fulfilling. I suspect it’s that way for most poets, who, when it comes down to it, seldom write poetry as their livelihood. Many, in fact, never get published or, like Emily Dickenson, are published extensively only after their death. And fame? Most find little within their lifetime, although some achieve it later. Sylvia Plath, for example, became really well known only after her death.

Thanks to the ease, convenience, and low cost of the Nook on-demand publishing platform, I’ve put together a couple of collections of poems in recent months. Published privately and never intended for sale, these volumes are gifts for family and friends. (The cover of the first one is pictured above.) Having worked in publishing and possessing an inclination for writing and design are helpful but not essential to this type of project.

In sum, the advice I’d give to anyone who is curious about writing, whether poems or some other form, is simply to do it. Ultimately, the intended beneficiary is the writer. If readers also benefit in some way, so much the better.

Note: This commentary is cross-posted on two blogs: Arts in View (http://artsinview.blogspot.com) and Living With…A Cancer Journal (http://livingwithcancerjournal.blogspot.com).

Published on February 28, 2016 06:02

January 20, 2016

A Divine Dolly

A new revival of the 1964 hit musical Hello, Dolly! is set to open on Broadway during the spring of 2017, according to TheaterMania (theatermania.com). The production will star Bette Midler as Dolly. All I have to say can be summed up in four words: It is about time!

A new revival of the 1964 hit musical Hello, Dolly! is set to open on Broadway during the spring of 2017, according to TheaterMania (theatermania.com). The production will star Bette Midler as Dolly. All I have to say can be summed up in four words: It is about time!As for many of my generation, the Divine Miss M has been a delightful fixture on the music and theater scenes over a lifetime. She captivated early on, in the days when she was delighting gay audiences, accompanied on the piano by Barry Manilow, at the Continental Baths in New York’s Ansonia Hotel, a period that produced, in 1972, her first album, The Divine Miss M. She memorialized that time in a later album, Bathhouse Betty, which was released in 1998. The Divine Miss M became a million-seller and earned her a Grammy Award as Best New Artist in 1973.

In 1979 Bette made her first movie, The Rose, and the title song will forever be associated with her. Success followed success as albums, movies, and stage performances accumulated, earning her numerous awards and a legion of devoted fans. I count myself as one of those fans, and now I’m delighted that she will be tackling the role of Dolly in a musical that I have enjoyed almost since it opened in 1964.

Hello, Dolly!,with music and lyrics by Jerry Herman and a book by Michael Stewart, based on Thornton Wilder’s 1938 farce, The Merchant of Yonkers, which was retitled The Matchmaker in 1955, opened on January 16, 1964, at the St. James Theatre. It was David Merrick’s first show. Choreographed by Gower Champion, it starred Carol Channing, who would make it a vehicle for her lifetime. She revived it in the 1970s and again in the 1990s. I saw it during the latter period, when Channing performed at the Indiana University Auditorium. However, much earlier I saw another touring production that began in 1965 and ran for two years and nine months and saw two replacements for Channing over the course of the tour. Eve Arden was one, and Dorothy Lamour, who gained fame in the Bing Crosby/Bob Hope road pictures of the 1940s. It was Lamour whom I saw when I was a college student in Kansas in the late 1960s.

The Bette Midler production will be the fourth Broadway revival of this iconic musical. I can hardly wait. It certainly seems to warrant a trip the Big Apple in 2017.

Published on January 20, 2016 06:35

November 23, 2015

Merton and Waugh

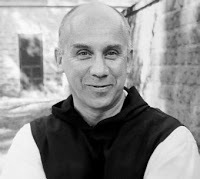

Thomas MertonMerton and Waugh, by Mary Frances Cody (Paraclete Press, 2015), recounts a relatively brief period from August 2, 1948, to February 25, 1952, during which the American author and monk Thomas Merton engaged in correspondence with the British novelist Evelyn Waugh. This slim volume, subtitled A Monk, a Crusty Old Man, and The Seven Storey Mountain, was a gift from my partner/husband Sam on the occasion of the fifteenth anniversary of our relationship, which coincidentally was our wedding day. I finished reading the book exactly three months later, not that it took that long to read the 155 pages but because I read it in digestible bits, allowing ample time to ponder this remarkable period of correspondence between these two interesting men whose lives were perhaps even more intriguing than their writing.

Thomas MertonMerton and Waugh, by Mary Frances Cody (Paraclete Press, 2015), recounts a relatively brief period from August 2, 1948, to February 25, 1952, during which the American author and monk Thomas Merton engaged in correspondence with the British novelist Evelyn Waugh. This slim volume, subtitled A Monk, a Crusty Old Man, and The Seven Storey Mountain, was a gift from my partner/husband Sam on the occasion of the fifteenth anniversary of our relationship, which coincidentally was our wedding day. I finished reading the book exactly three months later, not that it took that long to read the 155 pages but because I read it in digestible bits, allowing ample time to ponder this remarkable period of correspondence between these two interesting men whose lives were perhaps even more intriguing than their writing.The correspondence between Merton and Waugh began when Waugh was asked by Merton’s American publisher to edit the

Evelyn Waughmonk’s The Seven Storey Mountain manuscript for a British edition. Evelyn Waugh (1903-1966) was approaching middle age in 1948 and had recently become known in the United States following the publication some two years earlier of Brideshead Revisited, his novel of elicit love and divine grace. The manuscript of The Seven Storey Mountain, written by a Trappist monk living in obscurity in a rural Kentucky monastery, arrived unsolicited, sent by Merton’s editor Robert Giroux at Harcourt Brace, the New York publishing company.

Evelyn Waughmonk’s The Seven Storey Mountain manuscript for a British edition. Evelyn Waugh (1903-1966) was approaching middle age in 1948 and had recently become known in the United States following the publication some two years earlier of Brideshead Revisited, his novel of elicit love and divine grace. The manuscript of The Seven Storey Mountain, written by a Trappist monk living in obscurity in a rural Kentucky monastery, arrived unsolicited, sent by Merton’s editor Robert Giroux at Harcourt Brace, the New York publishing company.Thomas Merton (1915-1968) was not a novice writer at the time, although he was still somewhat new to monastic life, having been accepted at the Abbey of Gethsemani near Bardstown, Kentucky, as a novice monk in the spring of 1942. Early on it was recognized that Merton’s strength lay in his abilities as a writer, and he was set to work producing texts of various sorts as a means of bringing income to the monastery. The Seven Storey Mountain, written when Merton was in his early thirties, is autobiographical and unarguably his best-known book. The title refers to the mountain of Purgatory in Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Evelyn Waugh was not the only person Giroux approached to edit the work. Three others received unsolicited manuscripts: Graham Greene, Clare Booth Luce, and Bishop Fulton J. Sheen. But it was Waugh, who wasn’t expected to respond, who got the nod. Waugh’s endorsement was selected for the cover of the first edition: “I regard this as a book which may well prove to be of permanent interest in the history of religious experience. No one can afford to neglect this clear account of a complex religious process.” And so it has proven.

Cody has done a masterful job of parsing the two writers’ thoughts and feelings over the course of their exchanges. I suspect most readers will believe, as I do, that in peering into the letters these men exchanged they have been grant privileged access to a moment in time when the lives of these two writers intersected.

Published on November 23, 2015 17:34

October 19, 2015

Roman Empire Mysteries Delight

Marcus Didius Falco—If you don’t know this first-century detective from a superb series of mystery novels set during the early years of the Roman Empire, then you have missed many hours of delightful reading. Lindsey Davis (born 1949) is the English historical novelist who launched Falco onto the literary scene in 1989 with The Silver Pigs, set during the reign of the Emperor Vespasian (lived 9-79 CE; ruled 69-79 CE).

Marcus Didius Falco—If you don’t know this first-century detective from a superb series of mystery novels set during the early years of the Roman Empire, then you have missed many hours of delightful reading. Lindsey Davis (born 1949) is the English historical novelist who launched Falco onto the literary scene in 1989 with The Silver Pigs, set during the reign of the Emperor Vespasian (lived 9-79 CE; ruled 69-79 CE).In The Silver PigsFalco stumbles upon a conspiracy that involves trading silver ingots, and the investigation takes him to Britain. There he meets a lady above his station, the daughter of the senator who hired him, named Helena Justina. Against all odds, Falco not only solves the case but also falls in love with the noble lady—and she with him. However, they cannot wed until Falco is raised to the upper middle-class rank of equestrian. And that will take some doing. Thus the stage is set for an unfolding romance (and eventual marriage) that provides a continuing narrative through a long and thoroughly engaging series of novels.

Lindsey Davis, by taking this approach, created both a romantic backstory with three-dimensional characters whom readers become well acquainted with over a number of years and a problem. What happens to your main character (and those around him) as he ages? Moreover, what do you do when he retires? Davis deftly handles the issues of aging as Falco grows in his profession and the relationship between Falco and Helena Justina matures into a longterm marriage, complete with the introduction of children into the family dynamic.

I fretted that Davis might decide to retire with her detective, but in fact she took a more interesting and adventurous turn by focusing on Falco and Helena Justina’s adopted daughter, Flavia Albia. This daughter picks up where her father, now comfortably living in retirement, left off, becoming herself an “informer,” the role of first-century private detective. The first of the Flavia Albia novels is The Ides of April, published in 2013. Set in the spring of 89 CE, Flavia Albia even moves into Falco’s old, seedy apartment in Fountain Court, a rundown tenement that Falco now owns. As the story opens, she is a 28-year-old widow.

Davis adeptly negotiates the potential pitfalls of creating a believable female detective working subtly within the constraints of male-dominated Roman society. I recently finished reading Deadly Election, published this year, 2015, and could not be better satisfied with the continuation of this fascinating series through Falco’s daughter. I recommend this series, particularly to readers who love a good mystery and are interested in Roman history, for Davis’s intricately plotted stories also provide a convincing window into everyday life in Ancient Rome.

Published on October 19, 2015 15:47