Douglas Rushkoff's Blog, page 19

December 18, 2016

Circulate Interview – REPROGRAMMING OUR ECONOMIC OPERATING SYSTEM

Read this interview at Circulate

When you step back, it’s hard not to be blown away by the technological innovation in the world around us. Today, you can order deliveries by drone, take a ride in a self driving car, print physical objects on demand, travel to different worlds with virtual reality, and get schooled at board games by a computer.

Who saw this coming? Predictions about the future often underestimate the actual depth of change, and from some angles our world couldn’t look more different to that of 50, 100, or 500 years ago.

But Douglas Rushkoff thinks that some aspects of our economy haven’t changed. Some pretty fundamental aspects of our economy, at that.

It’s not there there’s a problem with the technology itself, but the framework that still guides most economic activity today. In his 2015 book Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, Rushkoff makes the case that the model of extractive growth – established long ago in the colonial period – is in dire need of an upgrade. Rushkoff argues that it’s for this reason that many influential business models of the past few years such as AirBnB, Spotify, Uber and Amazon haven’t necessarily delivered long-term benefits for the many, and may have increased inequality and stimulated concerns about privacy, safety and monopolisation.

So what could the new economic operating system be? Rushkoff suggests it’s one based on distributed networks, platform co-ops and the appreciation of land and labour as valued capital. Could the circular economy be the answer? Circulate will be tuning in to the livestream on the 23rd November to find out, and caught up with Douglas to get a preview of the discussion.

What does the term disruptive innovation mean to you?

I think of destructive destruction masquerading as creative destruction. I don’t mind innovations that disrupt existing markets as a byproduct of their superiority or efficiency. But I do mind innovation designed solely to disrupt existing, functioning marketplaces for the sole goal of establishing monopolies, extracting value, and then moving on. In the tech economy today, it’s almost exclusively the latter. Amazon destroys the book industry because it wants to establish a monopoly through which to leverage into new verticals. So it uses its war chest to undercut real booksellers in a scorched earth battle to own the industry. It uses that to leverage itself into retail, then uses that monopoly to pivot into mail services, drones, or anything.

Is the digital revolution really a revolution?

Well, it’s becoming one, which is a sad compromise of its greater potential to be a renaissance. Revolution is just the replacement of one power elite by another. That’s what happening. New super billionaires are replacing the old billionaires. Zero change, except for more poverty and greater ecological destruction. You really have to enslave a lot of people and destroy a lot of the planet to exact these sorts of changes. Renaissance, on the other, would be the rebirth of old ideas in a new context. Old ideas like p2p economics, local currencies, value creation and exchange, the return of land and labor to the factors of production. These repressed, often illegalised economic mechanisms are retrieved, leading to an economic fabulousness that’s hard to imagine.

Which big trend – be it economic, social, technological or otherwise do you feel will be most disruptive in the coming 20 years?

The loss of the natural environment will be big. People need air, water, and food. It’s so hard to do that without oxygen, oceans, and other species. That really is the big one.

A lot is written about what the current disruptive trends mean for businesses and governments, but what do you think the impacts will be on the majority of the population?

Unless there’s substantial change, economic disruption perpetrated solely for the benefit of short term venture capital leads to greater disenfranchisement of labor. Labor is the majority of the population, even if their jobs have been replaced by machines. What we need to remember is that jobs weren’t invented simply because we need to get stuff done. They allow people to participate by creating value.

Tech innovation is seductive and happens quickly. Who is responsible for ensuring that we don’t follow a path to a future we didn’t really want?

Everyone. But for now, it’s the technologists actually developing things. They hold the keys. The kids graduating Stanford don’t have to go work for Goldman Sachs writing extractive algorithms. The developers and engineers need to embrace their power, rather than submit to the operating system of Wall Street. It’s so sad that they see themselves as powerless lackeys of the moneyed elite, rather than the true power players of the century. But I guess they’ve been brainwashed to seek out “unicorns” instead of creating the world they want to see.

What message or main idea would you want this audience to remember from your talk?

We don’t have to accept the rules of a 13th Century, printing press era operating system for our 21st Century economy. Real disruption would mean challenging the underlying OS, not just installing more extractive software on top of it

The post Circulate Interview – REPROGRAMMING OUR ECONOMIC OPERATING SYSTEM appeared first on Rushkoff.

Circulate – REPROGRAMMING OUR ECONOMIC OPERATING SYSTEM

Read this interview at Circulate

When you step back, it’s hard not to be blown away by the technological innovation in the world around us. Today, you can order deliveries by drone, take a ride in a self driving car, print physical objects on demand, travel to different worlds with virtual reality, and get schooled at board games by a computer.

Who saw this coming? Predictions about the future often underestimate the actual depth of change, and from some angles our world couldn’t look more different to that of 50, 100, or 500 years ago.

But Douglas Rushkoff thinks that some aspects of our economy haven’t changed. Some pretty fundamental aspects of our economy, at that.

It’s not there there’s a problem with the technology itself, but the framework that still guides most economic activity today. In his 2015 book Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, Rushkoff makes the case that the model of extractive growth – established long ago in the colonial period – is in dire need of an upgrade. Rushkoff argues that it’s for this reason that many influential business models of the past few years such as AirBnB, Spotify, Uber and Amazon haven’t necessarily delivered long-term benefits for the many, and may have increased inequality and stimulated concerns about privacy, safety and monopolisation.

So what could the new economic operating system be? Rushkoff suggests it’s one based on distributed networks, platform co-ops and the appreciation of land and labour as valued capital. Could the circular economy be the answer? Circulate will be tuning in to the livestream on the 23rd November to find out, and caught up with Douglas to get a preview of the discussion.

What does the term disruptive innovation mean to you?

I think of destructive destruction masquerading as creative destruction. I don’t mind innovations that disrupt existing markets as a byproduct of their superiority or efficiency. But I do mind innovation designed solely to disrupt existing, functioning marketplaces for the sole goal of establishing monopolies, extracting value, and then moving on. In the tech economy today, it’s almost exclusively the latter. Amazon destroys the book industry because it wants to establish a monopoly through which to leverage into new verticals. So it uses its war chest to undercut real booksellers in a scorched earth battle to own the industry. It uses that to leverage itself into retail, then uses that monopoly to pivot into mail services, drones, or anything.

Is the digital revolution really a revolution?

Well, it’s becoming one, which is a sad compromise of its greater potential to be a renaissance. Revolution is just the replacement of one power elite by another. That’s what happening. New super billionaires are replacing the old billionaires. Zero change, except for more poverty and greater ecological destruction. You really have to enslave a lot of people and destroy a lot of the planet to exact these sorts of changes. Renaissance, on the other, would be the rebirth of old ideas in a new context. Old ideas like p2p economics, local currencies, value creation and exchange, the return of land and labor to the factors of production. These repressed, often illegalised economic mechanisms are retrieved, leading to an economic fabulousness that’s hard to imagine.

Which big trend – be it economic, social, technological or otherwise do you feel will be most disruptive in the coming 20 years?

The loss of the natural environment will be big. People need air, water, and food. It’s so hard to do that without oxygen, oceans, and other species. That really is the big one.

A lot is written about what the current disruptive trends mean for businesses and governments, but what do you think the impacts will be on the majority of the population?

Unless there’s substantial change, economic disruption perpetrated solely for the benefit of short term venture capital leads to greater disenfranchisement of labor. Labor is the majority of the population, even if their jobs have been replaced by machines. What we need to remember is that jobs weren’t invented simply because we need to get stuff done. They allow people to participate by creating value.

Tech innovation is seductive and happens quickly. Who is responsible for ensuring that we don’t follow a path to a future we didn’t really want?

Everyone. But for now, it’s the technologists actually developing things. They hold the keys. The kids graduating Stanford don’t have to go work for Goldman Sachs writing extractive algorithms. The developers and engineers need to embrace their power, rather than submit to the operating system of Wall Street. It’s so sad that they see themselves as powerless lackeys of the moneyed elite, rather than the true power players of the century. But I guess they’ve been brainwashed to seek out “unicorns” instead of creating the world they want to see.

What message or main idea would you want this audience to remember from your talk?

We don’t have to accept the rules of a 13th Century, printing press era operating system for our 21st Century economy. Real disruption would mean challenging the underlying OS, not just installing more extractive software on top of it

The post Circulate – REPROGRAMMING OUR ECONOMIC OPERATING SYSTEM appeared first on Rushkoff.

December 16, 2016

Open Democracy UK – Re-writing the Core Code of Business

Read this interview at Open Democracy UK

Douglas Rushkoff is a writer, documentarian, and lecturer whose work focuses on human autonomy in a digital age. He is the author of fifteen bestselling books on media, technology, and society, including Program or Be Programmed, Present Shock, and most recently Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus.

He recently authored a chapter of the new book on Platform Co-ops Ours to Hack and Own, in which he states:

“Platform cooperatives – as a direct affront to the platform monopolies characterizing digital industrialism – offer a means of both reclaiming the value we create and forging the solidarity we need to work toward our collective good. Instead of extracting value and delivering it up to distant shareholders, we harvest, circulate, and recycle the value again and again. And those are precisely the habits we must retrieve as we move ahead from an extractive and growth-based economy to one as regenerative and sustainable as we’re going to need to survive the great challenges of our time.”

In the run up to the Open 2017 – Platform Co-ops conference in London, I explored some of Douglas’ ideas with him:

OSB: You’ve mentioned that “the model of the ever expanding economy is bankrupt” and highlighted the “corporate charters” and “central currency” as the core components of the present “bankrupt” system. How can we hope to challenge the corporate charters?

DR: Well, you sound like you believe the way to change corporate structure is for citizens to take action against the corporations. That’s certainly one possible approach, and useful in a situation where there are no human beings within the corporation who are willing or able to change the corporations from the inside. What might be surprising to you is that most of the people in corporations actually do not want to kill people, do not want to be enslaving children in resource-rich nations, and do not want to make the planet uninhabitable. They are the ones in the best position to change corporate actions, since they are inside the companies themselves.

They simply need to be educated about what is possible. I tried to do some of that in my book. CEOs and Boards of Directors need to understand that they do have legal authority to act in the best long term interests of the company. So-called “activist” shareholders really cannot sue Boards for hurting the short-term value of shares – especially when the Boards are acting in the long-term interests of the shareholders. Not destroying the planet is in the best long-term interests of shareholders. Likewise, companies can restructure and reorient from within to favor dividends and public reinvestment over capital gains and extraction.

So, as I argue in my book, the key is to convince CEOs and others who are running corporations that they can exercise human agency in their decisions. They do not have to behave automatically. They can use their decision-making authority. They need to communicate with shareholders, and explain the advantages of getting lots of dividends instead of a one-time “pop” of share price, followed by an inevitable decline. Companies can actually make more money with ongoing revenues than blindly pursuing growth.

They can stop selling off their most productive assets, and instead remain powerfully competent companies. Steady state economics is about maximizing circulation rather than extraction. To anyone who understands how business works, they should see how this is a healthier choice for those within the business, as well as the distant shareholders who only want money at any cost.

OSB: You have described how “digital giants are running charter monopoly software…” and that their “technology enforces the monopoly”. At Open we are keen to see NGOs, co-ops, non-profits and even Local Authorities start to utilise open source software and, in return, to fund the development of a suite of open source apps which facilitate collective ownership and collaboration. What steps do you think are required to disrupt the digital giants’ monopolies?

DR: Of course, I was using the word “software” a bit metaphorically. The corporate charter is itself a program that can be changed. Instead, it is being further amplified by technology. What I mean by that is that the corporation works in a particular way, as dictated by the charters and contracts making up their business plan. So a company’s core code – long forgotten – may assume that the way to make money is to prevent people in the regions where the company operates from making any money. And while that may have been a good strategy for maintaining a slave state in the 1400’s, it doesn’t work so well in places where people are supposed to be free or employed.

But the company’s directors may have forgotten all of this by the 21st century, and simply implemented new plans based on the same strategy of exploitation and extraction. So now they are writing software and building platforms that embed these same assumptions about their users. And they end up extracting value and time from people without helping them create or retain any for themselves.

Or a business plan might be to make money by extracting metal ore from the ground. Then, the company builds technology to do that, which makes the extraction happen a lot faster. They don’t realize that extracting so quickly and totally may deplete things in new ways. And because they don’t realize that the core “code” of the company is actually changeable, they don’t see any way out of the problem.

Now, you’re talking about software solutions themselves, and how people from the outside can give up entirely on the corporate solutions, and build alternative software that works in greater consonance with the needs of real people and places. That’s pretty easy to do. We can write an alternative Uber that lets the drivers participate in the profits. Or an alternative Facebook that doesn’t manipulate people’s news feeds to try to program people’s future choices. The trick is getting people to use the alternatives when they’re not so pretty or universally accepted.

OSB: It has been suggested that the open-source / platform co-op alternatives to corporate software solutions will need to do two things at least:

– Be easier to use / provide a better experience

– Cost the user the same or less (i.e. provide better value for (conventional) money.

What do you think about the possibility of an “open app ecosystem” (a library of interoperable apps, covering all aspects of communication, organisation and even trading needs) sweeping into dominance over the corporate alternatives once it provides the same level of utility, at the same price, as the present corporate systems?

DR: The easiest tactic is to help people experience the impact of various pieces of software on their own existence. Does Facebook make them happier? How is it helping them take command of their lives? People sometimes have to become more aware of the surveillance state, the extractive quality of these tools, and the nauseous, empty, angry feeling they have after using this stuff in order to feel motivated to make a change.

OSB: Your chapter in Ours to Hack and Own entitled ‘Renaissance now’ explains how we are on the verge of a modern-day renaissance. There is no doubt that revitalising and retrieving lessons, techniques and habits from the past could help bring about change but the last renaissance was also driven by a shift in intellectual thinking. Do you have any thoughts on how, and where, an intellectual shift might come from?

DR: I think changes in experience can change people’s world view. If they have terrific experiences working in co-ops or using local currency or simply sharing stuff, then their world view will change.

OSB: You explained how “banks were invented to extract value from our transactions not to authenticate transactions”. Do you have any thought on why LETS and time banks haven’t made a more effective transition to the web?

DR: I think part of the reason LETS and alternative, trust-enabling systems have not developed is that most people are not actually proud of the value they create. Too many people feel that they don’t have enough to offer, and need to hide behind anonymous cryptocurrencies and traditional anonymizing monetary systems in order to mask things. Meanwhile, if a person is sitting in a cubicle working for a mortgage broker or collecting debt from student loans, how are they supposed to participate in a local LETS system? What real value are they creating for others? Such people find it easier to take some of the cash they’ve made and “invest” it in Ethereum than… become part of some local favour bank. To create and exchange value, you have to be able to create some value for other humans – not just help some corporation extract value from people.

OSB: I am excited about the idea that platform co-ops and the collective ownership of our local facilities and businesses could potentially completely disrupt capitalist democracy as we know it. Where do you stand on ‘working with and within the present system’ vs ‘building a new system which makes the present system obsolete’?

DR: Well, I don’t think it’s one or the other. People can vote on public and municipal activities through traditional democratic participation, and people can vote on private and business activities through their participation in cooperatives. I do believe that the more influence real people have on the private sector, the more freedom our public activities will be from corporate control. A platform cooperative is not going to lobby the government for destruction of the environment where its workers are living. So government ends up able to deal with reconciling the different views of its people, rather than that of its people with that of its non-human corporate actors.

OSB: Do you think there is a direct correlation between the amount of external investment an organisation accepts (and hence ownership / governing authority it relinquishes) and the real value an organisation has for society?

DR: Well, it has more to do with how much a business actually needs to operate and satisfy its market. If a business is really inexpensive to operate, then it doesn’t make sense for that business to take billions of dollars in investment. I know that sounds crazy, but it’s true. If you take billions of dollars of investment, then the people who gave you that money expect to get that money back. This means you need to make billions of dollars in revenue. That’s really hard – especially if you’re a small business that can actually function with just a few thousand dollars. If you take less money, then you are not obligated to grow the business so fast. You are still *allowed* to grow your business fast, but you don’t have to become a multi-billion-dollar business right away.

The more money you take, and the less proportioned to the real size of your business, the more power you have to surrender to the people giving you the money.

OSB: We are often exposed to the vision of a world full of hate and extremism and scarcity but rarely hear about a positive alternative. If platform co-ops, the solidarity / generative economy take hold it strikes me we could be living in a very different world in the future. Can you describe what you think this world might look like?

DR: I’m not a utopian, so I don’t envision a world or economy entirely transformed into a new state where all the value people create is properly registered, the commons is reinstated and appropriately governed, and selfishness is exchanged for true compassion.

The generative, solidarity-inspired economy I envision is one where humanity stands a good chance of making through the next century without going extinct. I am trying to envision a world where global warfare won’t be the only way to prevent impoverished populations from enacting violent revolutions on their own governments. I’m imagining a world where the wealthy don’t simply try to earn even more money in order to insulate themselves from the problems they’ve created by “externalizing” the real costs of their business practices.

So the radical alternative I’m envisioning is simply a world where the most extractive and destructive practices don’t absolutely dominate us. Where people have the ability to work for one another if there are no corporate jobs available.

I can imagine a near future without people starving in the streets, without China cashing in its chips by purchasing America’s greatest companies and properties, and without a continuation of the shift of wealth from the poor to the rich. I can imagine it not getting significantly worse than it is now, but that will take a huge shift in power and attitude.

OSB: What do you see as the main stepping stones for this vision to become a reality?

DR: Well, from a policy standpoint, I think a shift in tax policy would do a lot: punish capital gains and reward dividends and revenue. Right now, we punish companies and people who earn money, and reward those who simply extract capital out of the economy. That has to be reversed.

People and companies have to look toward earning money with the thing they do, rather than by selling the company itself. You can earn money, or you can “flip” your business (sell it to short-term investors). The latter leads to really bad practices.

We also have to accept that growth is an artefact of a currency system, not necessarily a symptom of a healthy economy. There are some economies that may be full grown.

OSB: Thanks Douglas, you have given us plenty of food for thought. The proposal that the users might buy back Twitter seems to demonstrate the growing appetite for platforms which are owned and controlled by their members. Here’s hoping more people start to realise the benefits of member ownership and governance, and how this creates a virtuous cycle of value creation. As you say, it seems essential if we’re going to survive the great challenges of our time.

The post Open Democracy UK – Re-writing the Core Code of Business appeared first on Rushkoff.

December 15, 2016

P2P Foundation – When Memes Fail Us

Read this article at P2P Foundation

I know this has been a rough time for a lot of you, and I hope you are doing well. In brief: Yes, there has been a major electoral upheaval, and it seems there are many confused people out there working under some pretty strange assumptions. But no, this isn’t as much of a shift as it may seem.

If anything, this is the legacy of the 20th Century coming back to haunt us. In an effort to counter the propaganda of our political enemies, American social scientists (Bateson and Meade, to be exact) proposed a world of screens they called “the surround.” Their idea was that if people had the experience of choosing different things – or of looking at whichever screen they wanted to – they wouldn’t care so much that all the choices were for essentially the same thing.

In short, looking at a screen – any screen – was more important than what a person learned or came to believe, other than that he or she was experiencing real autonomy and choice. That was supposed to be America: the land of choices. The supermarket offers us fifty different laundry detergents to choose from – even though they are almost all the same, and are distributed by the same two or three corporations. You can choose whichever one you want, as long as you choose (and pay for) one of them.

An array of TV channels gave us a similar experience of choice. But Bateson and Meade probably never imagined a world with quite as many screens as ours now has. Or as much of a direct connection between our experience of screen choice and that of democracy. American Idol and other reality programs made the connection discrete. And thus Donald Trump’s migration from reality TV to electoral politics was seamless. Social media and smart phones took screens to the next level of illusory user-control, while they simply reduced the array of possibilities to a narrow beam of sensationalist, algorithmically assembled, self-affirmation.

But the underlying techniques for influencing people through all those screens? That’s magic. Or at least the approach to magic practiced by Hitler and his propagandists in WWII, before it was utilized by the British and American advertising agencies after the war. It’s the subject of the graphic novel I released last week – Aleister & Adolf – about the occult war between Aleister Crowley and Adolf Hitler at the end of WWII. I hadn’t meant it to be quite so prescient, but it’s a great way of understanding how we got where we are. The social media landscape is the ideal space for sigils and memetic engineering because we are utterly untethered from grounded experience. Those who succeed at these techniques are the ones who successfully tap into existing hidden agendas in popular culture. They just jump into the unacknowledged standing wave of society, and it carries them along for the ride. It’s not the subject or surfer that matters so much as the wave itself, and one’s willingness to surrender to it entirely. That’s why celebrities or candidates who adopt this strategy end up seeming to have no coherent goal.

On the bright side, I think running a government as large as ours is really hard. Trump’s obsession with his Twitter feed will keep him more than occupied over the next months of his presidency. The bigger issue is whether his hiring of people who have never worked in their assigned fields before (Ben Carson at HUD?) will lead to large parts of the government simply not working. It’s not a good moment to count on FEMA, the FTC, or Department of the Interior.

But a paralyzed, incompetent federal administration will simply require people to develop more local mechanisms for economic recovery, social cohesion, and mutual aid. This means red and blue people working together to maintain the basics of civil society, from food supply chains and healthcare to education and peaceful streets. With neoliberalism and supra-national corporations at bay for a moment, we may actually have more of an opportunity to develop bottom-up alternatives than we’ve had for a long time. The Depression spawned local currencies, farm cooperatives, and new mechanisms for distributed prosperity. Those of us with a foot in the real world stand a chance of building similar tools and networks, today.

Meanwhile, look for solidarity wherever you can find it. Sometimes it involves working with or helping people we don’t even like. Imagine that. My TeamHuman.fm show is an effort in that direction, but I’ll be working hard to engage with more guests who don’t already agree with me on what it means to be human or how best to express it.

I’m also committed to getting off the factual news cycle and deeper into the cultural psyche. I’ve been writing factual books for a decade now, and I feel like they only reach people who have already reached the right conclusions and are simply looking for ways of backing up their newfound sensibilities. That’s a noble role to fill, for sure, but I want to open some new minds, and to do that I may have to shift from scholarly research to cultural alchemy. More to come…

The post P2P Foundation – When Memes Fail Us appeared first on Rushkoff.

Dangerous Minds – RUSHKOFF ON HIS NEW GRAPHIC NOVEL, CROWLEY AND MAGICAL WARFARE

Read this interview at Dangerous Minds

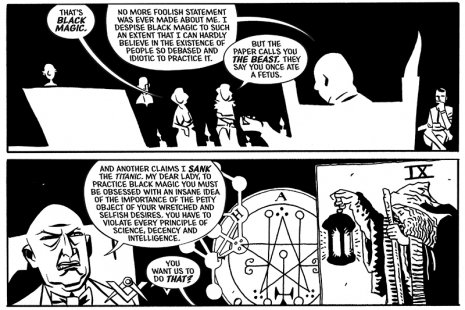

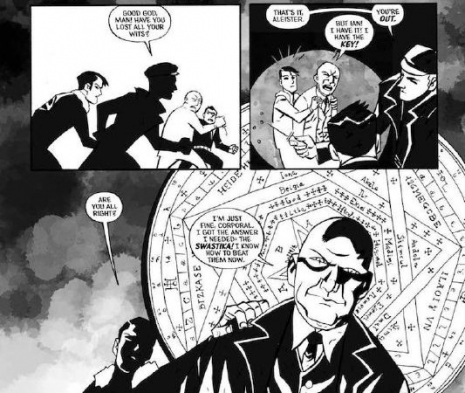

Aleister & Adolf is a new graphic novel from Dark Horse Comics, the product of the creative pairing of media theorist Douglas Rushkoff—Professor of Media Studies at Queens College in New York—and and award-winning illustrator Michael Avon Oeming.

In Aleister & Adolf the reader is taken behind the scenes of the capitalist spectacle and inside the boardrooms where corporate-occult marketing departments employ fascist sigil magick developed by the Nazis during WWII in today’s advertising logos. A place where the war for men’s minds is waged with symbols and catchy slogans. It’s a fun smart read and you’ll be much smarter after you’ve read it, trust me. And Oeming’s crisp B&W artwork is perfectly suited for getting across some often difficult and tricky philosophical concepts. He’s a unique talent indeed.

Rushkoff recently told AV Club:

“Swastikas and other sigil logos become the corporate logos of our world. And given that we’re living in a moment where those logos are migrating online where they can move on their own, it’s kind of important that we consider the origins and power of these icons.”

Grant Morrison even wrote the introduction to Aleister & Adolf. I mean, how can you lose with something like this?

I asked Douglas Rushkoff a few questions via email:

Dangerous Minds: Where did you find the inspiration for Aleister & Adolf?

Douglas Rushkoff: It’s almost easier to ask where didn’t I find inspiration for Aleister & Adolf. The moment it occurred to me was when I was in an editorial meeting at DC/Vertigo about my comic book Testament, back in 2005. The editor warned me that there was an arcane house rule against having Jesus Christ and a Superhero in the same panel. Not that I was going to get to Jesus in my story, but the rule got me thinking about other potentially blasphemous superhero/supervillain pairings. And that’s when I first got to wondering about Aleister Crowley vs. Adolf Hitler.

But as I considered the possibility, it occurred to me that they were practicing competing forms of magic at the same time. And then I began to do the research, and learned that the premise of my story was true: Aleister Crowley performed counter-sigils to Hitler’s. Crowley came up with the V for Victory sigil that Churchill used to flash—and got it to him through Ian Fleming (the James Bond author) who was MI5 at the time.

I’ve always wanted to do something about Crowley, but I’ve been afraid for a bunch of reasons. Making him something of a war hero, and contrasting him with a true villain like Hitler, became a way to depict him as something more dimensional than “the Beast.”

Did you think of the ending first? It’s a bit like a punchline, isn’t it?

Douglas Rushkoff: I didn’t think of the ending first. The first thing I thought of was to have a young American military photographer get sent to enlist Crowley in the magical effort. I wanted us to see the story through someone like us—someone more cynical, perhaps—and then get to have the vicarious thrill of being drawn into Crowley’s world.

Then, I decided I needed a framing story – just to show how relevant all this creation of sigils is to our world today. So I created a prologue for the story, that takes place in a modern advertising agency: the place where the equivalent of sigil magic is practiced today. I wanted to set the telling of the story within the frame of how corporate sigils are taking life on the Internet today. So the outer frame takes place in the mid-90’s, when the net was being turned over to marketers. The ending is pretty well broadcast up front.

Aleister & Adolph reminds me a lot of Robert Anton Wilson’s Masks of the Illuminatus—which I think is his best book—because it sort of forces its ideas into the reader’s head like an earworm that you can’t resist. Also Crowley is a character in that book, too, of course. Do you see it as a bit of a RAW homage?

Douglas Rushkoff: It’s a RAW homage in that the story has verisimilitude—it is told in a way where it’s absolutely possible for this all to happen. There’s no supernatural magic here; it’s just the magick of Will. There’s the black magic of the Nazis. But however extreme the Nazis, it was real. It’s got the reality quotient of Eyes Wide Shut or Apocalypse Now.

And that’s the understanding of sigil magic I got from Bob. It’s all very normal. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t work. Just that you have to participate in its perception. It’s just a different way of understanding the connections. So while the protagonist of the story starts off as a disillusioned atheist and ends up believing in magick as Magic, even Crowley (at least my Crowley) tries to convince him not to take it so literally.

I wouldn’t understand magick that way if it weren’t for Bob. It’s embedded in the fabric of reality. It doesn’t need to break the rules of reality to work.

Are you aware of a recent trend among some alt-right types to organize acts of group 4Chan “meme magick”? Some of it’s just blatant harassment and bullying over Twitter, but there’s actually a sophisticated intent behind some of it. Pepe the Frog has become a hypersigil. I’m not being admiring of it—the idea that certain reichwingers would want start a magical war via social media is alarming to say the least—but the concept is a sound one magically speaking: They’ve figured out how to amplify their signal’s strength like a radio transmitter.

Douglas Rushkoff: There’s a real crossover between the alt-right and the occult. I knew a guy writing a book about it, in fact. And remember, it was one of Bush’s advisors who once explained that the future is something you create. And there’s an any-means-necessary quality to libertarianism that is consonant with chaos magic.

Plus, you’re talking about homespun propagandists inhabiting the comments sections of blogs and things. They’re not reading Bernays and Lippman. They’re waging hand-to-hand battle in the ideological trenches. A bit of NLP, rhetoric, and magic are what you turn to.

The interesting thing here is why the left does not use these techniques. It goes against our sense of what is fair. We know we’re “right” and so we want to win with the fact. Sigil magic feels like cheating on some level. So we have to ask ourselves, isn’t the full expression of our Will something we want to unleash? If not, why not?

This isn’t the freethinking/pansexual “Generation Hex” types who seemed to be on the horizon a few years ago, but rather like an evil skinheads contingent at Hogwart’s.

Douglas Rushkoff: Alas it is not. That’s partly because the freethinking pansexuals got a bit distracted by other things. And most of them worked alone. I don’t think there were nearly as many, either. That’s pretty rarified air. Back in the 80’s, there were more kids taking acid in the parking lot at AC/DC concerts than there were in the dorms of Reid College. And likewise – as a result of economics as much as anything – there’s more gamergaters throwing sigils online than Bernie Sanders supporters. Sometimes magic gets in the hands of people you’d rather not find it.

The post Dangerous Minds – RUSHKOFF ON HIS NEW GRAPHIC NOVEL, CROWLEY AND MAGICAL WARFARE appeared first on Rushkoff.

December 14, 2016

The Tyee – Next Economy: Tech Capitalism’s Impossible Dream

Read this interview at The Tyee

Douglas Rushkoff has been observing the Internet’s trajectory since the 1990s, writing 16 influential books about digital culture along the way including Media Virus and Present Shock. Rushkoff’s latest work, Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, focuses on the business and investing practices of today’s leading tech companies like Uber and Snapchat, and how they are exaggerating the worst aspects of an economic system that pushes for growth at all costs.

The Tyee sat down with Rushkoff to talk about his perspective on the hottest digital platforms that are reshaping our daily life.

The Tyee: Let’s start by talking about the growth model of today’s tech startups: I was just looking at the numbers yesterday and Snapchat is valued the same as Deutsche Bank, a major European financial institution — what does this mean?

Douglas Rushkoff: What we’re looking at is a basic kind of pyramid scheme. I don’t usually talk about it like this, but the people who found and invest in [today’s] digital startups are largely doing it in order to flip them.

It doesn’t actually matter if the company makes revenue, supports a marketplace, or has any true longevity in front of it. What matters is that it can sell its shares for 100-times whatever that last round of people bought them for.

Look at a company like Twitter. Like it or not, Twitter makes $2 billion dollars a year on its 140-character messaging app. That’s considered an abject failure by Wall Street, because $2 billion is about all Twitter can figure out how to make. They’ve plateaued at this level. It doesn’t matter that the company has revenues or that it could be extremely profitable for everybody involved. All that matters is whether they can go from a $2 billion company to a $4 billion company, and get their share price to grow. This is what it means for companies like Snapchat, Facebook to be considered “successful.” They can get someone else to buy their shares for more than the last round of people put in.

To be successful in this game, a company needs to show that it can establish a monopoly in a particular vertical, and then pivot from that vertical to another one, into another one, and so on and so on. This is the Amazon model of, “we’re going to go and take over the book industry”; not because they need there to be a book industry 10 years from now, but because establishing a monopoly in that book industry lets you grow into another industry, and another one. So Snapchat looks like they’re going to “win” messaging on some level and that means that they should be able to leverage that win into something else and something else.

This growth profile geared toward digital platform domination is something that seems different about this recent round of successful tech startups. How is this affecting innovation in the economy?

This is changing the science of innovation from a focus on how to serve customers, or create new marketplaces, into something much more cyn-ical. Innovation now means: “How can we exploit the monopoly we’ve created or extend that monopoly?”

This is not particularly new to digital. This is what Wal-Mart did through establishing a monopoly of big box stores. I don’t know that Wal-Mart has this so much anymore now that there is an Amazon, but there was a point at which companies really had to decide, “Do I want to sell through Wal-Mart, or do I want to sell in every other way?” If you want to sell through Wal-Mart then you have to adapt your business to use their RFID tag system and distribution scheme. You have to reconfigure your whole business around producing for Wal-Mart and Wal-Mart’s shelves and Wal-Mart’s way of tagging things.

There’s a company called Seamless here in New York, which essentially has a monopoly on restaurant delivery. They have an app like Uber, but for restaurant delivery. What most people don’t know is that since Seamless established this monopoly, they make it extremely hard for a restaurant to survive if they aren’t using their app. And then if you don’t pay Seamless extra money, their algorithm changes so your restaurant shows up lower in the list. Now restaurants are paying upwards of 25 per cent of their bill to a company that’s just replicating what the restaurant could already do on its own. You could already call a restaurant and order food to be delivered. But if you want the convenience of the app, and you want to be able to choose the restaurant through the app, now the establishment of that monopoly lets them tighten their grip and force restaurants to choose whether you’re with us or against us.

If you’re against an app with a monopoly, you’re in trouble.

Platforms like Uber are extremely convenient. I used it a lot when traveling after it first launched because it is so simple and fast compared to hailing a cab. But is this convenience sustainable?

What Uber ultimately looks like is a total destruction of the taxi business. In other words, they will make taxi driving so unsustainable for the drivers that all the drivers go out of business, and the industry is itself decimated. Then you will see alternatives emerge, if they’re not already emerging.

This is like what happened when Clear Channel, basically a big marketing company, used their huge war chest to buy most of the FM radio stations all around the United States. They incorrectly believed that radio was a growth industry and that consolidating all these stations, and running them from a single warehouse out in Utah or somewhere, rather than having local DJs and local sales and all, this space could be commodified and centralized, and everything could be run by computers.

This action destroyed the local fabric of the FM radio universe.

Eventually Clear Channel realized they couldn’t make any money this way. There wasn’t any money to be made. People stopped listening because part of what makes terrestrial radio special is that it is deeply local. There’s some sort of local flavour, and some sense of interaction with the broadcaster. They sold all of the stations, giving up what they destroyed. This entire process didn’t achieve anything because it’s hard to rebuild an ecosystem after it’s been destroyed, especially a cultural ecosystem. And for this same reason, I don’t see Uber staying in the ride sharing business for so long. I don’t even see Amazon necessarily staying in the book industry. Amazon doesn’t really care that the local bookshop is returning now because that book market provides such a low profit compared to cloud services and the other sorts of things that Amazon wants to monopolize now.

You write about the growth trap that we’re facing throughout the economy at large. This brings up the question of whether the digital economy can expand forever. A lot of people tell me that even though there might be limits to physical growth of roads and the amount of oil we use and carbon we put in the atmosphere, with dematerialization, modern technology makes it possible to keep economic growth going. In fact, we can grow the digital economy without limits. What would you say to that?

The argument, which isn’t new, is that we have infinite real estate online. This would be true except that human beings are needed to pay for this value, and our attention only has so much surface area. Living in a digital economy that wants to expand forever is part of why we’re experiencing what I’ve been calling “present shock.”

Present shock is an assault on our attention from this always-on reality where our cell phones are strapped to our bodies so that we can be updated and interrupted every time somebody tweets about us, or our boss wants us, or there’s a new offer at the Gap or something. Notification is not a feature, it’s a nightmare. I shouldn’t care about any of that if I’m living my own real life. This eventually runs up against limits because profit-seekers can take people’s every waking hour, every sleeping hour, and every subconscious hour, and broadcast to them simultaneously. This would create a demand for pharmaceuticals in a world where everybody’s being assaulted constantly like that. But then either the population needs to keep growing, or we reach a point where even our attention has been used up, and people start pushing back by spending less time online, and less time on phones.

If this continues, these devices are going to become so nauseating that the consumers everyone is after will resist these things. You’re going to see “turn off movements” and people going to restaurants and turning off their phones, or maybe choosing to spend more time making love away from their devices. That’s a serious problem for those who demand that we be “on” every second.

We’ve had so much value extracted from us that if we have no money, then what’s the point of being online all the time? So we can have data extracted from us instead? Data is the biggest bubble of all. Every single company out there has an ultimate exit strategy as a big data play. The problem is that all this data is from bankrupt people. Everybody’s already got the data. So the data is going to become the cheap commodity. I don’t see that plan working out either.

There is an understandable logic in the idea that online real estate is infinite. But just as we found out in the web of 1998, just because you have infinite online real estate and tens of billions of HTML pages, this doesn’t mean there’s enough eyeball hours of human time to absorb all of it.

Years ago it was a lot of fun to be part of the first generation of people using peer-to-peer sharing apps like Kazaa and Napster, sharing data between hard drives of real people. It seemed like there was an endless frontier of information to be discovered on the Web. But over the last few years this feeling seems to be shrinking. Any information that’s valuable is going behind paywalls, or buried in pages dominated by ads like Huff Post’s. Is there hope for returning to that original kind of fun hacker culture that existed in the ‘90s and early 2000s where information existed to be liberated and democratized?

The hope isn’t that the whole Web may shift back. It’s that the Web or the Internet will be able to accommodate a parallel culture of participation of art, community and peer-to-peer activity. The way that the Net is going, even most digital publications which were formerly magazines are moving on to Facebook, using it as their distribution platform because people don’t even go to the home pages of most publications. All the traffic is received sideways through social media. If publications want to stay high in the social media platforms algorithms, they’ve got to move in, lock stock and barrel.

The early Internet had America Online, and a lot of people thought America Online was the Internet, but it was actually a walled garden that wasn’t even connected to the Internet for a while. Eventually people realized there was something much more out there. And it was inevitable that those walls would fall because people would want to be out on the greater net and actually in the real world. Now it looks like Facebook has enough power and enough members and enough people who really look at the world through its algorithms that a lot of digital culture is moving on to their site as a way of protecting themselves. That’s a negative development as far as I see it.

On the other hand, there are still people interested in what we now call the Open Web. The Open Web is really just the original web idea: that you maintain your own web site instead of going onto these giant centralized platforms, and that you use protocols for one web site to connect with another one. It’s something much closer to the early Internet dream of a large network of nodes that are connected.

I think as people realize they can’t get jobs in this highly centralized digital economy, as companies realize that it might be better to beat them than join them, I think we will see the retrieval of some of these earlier networking values.

Listen to more Douglas Rushkoff: This was only the start of our conversation with Rushkoff. You can listen to the interview as it continues by clicking here.

The post The Tyee – Next Economy: Tech Capitalism’s Impossible Dream appeared first on Rushkoff.

December 8, 2016

Dangerous Minds Interview:

Aleister & Adolf is a new graphic novel from Dark Horse Comics, the product of the creative pairing of media theorist Douglas Rushkoff—Professor of Media Studies at Queens College in New York—and and award-winning illustrator Michael Avon Oeming.

In Aleister & Adolf the reader is taken behind the scenes of the capitalist spectacle and inside the boardrooms where corporate-occult marketing departments employ fascist sigil magick developed by the Nazis during WWII in today’s advertising logos. A place where the war for men’s minds is waged with symbols and catchy slogans. It’s a fun smart read and you’ll be much smarter after you’ve read it, trust me. And Oeming’s crisp B&W artwork is perfectly suited for getting across some often difficult and tricky philosophical concepts. He’s a unique talent indeed.

Rushkoff recently told AV Club:

“Swastikas and other sigil logos become the corporate logos of our world. And given that we’re living in a moment where those logos are migrating online where they can move on their own, it’s kind of important that we consider the origins and power of these icons.”

Grant Morrison even wrote the introduction to Aleister & Adolf. I mean, how can you lose with something like this?

I asked Douglas Rushkoff a few questions via email:

Dangerous Minds: Where did you find the inspiration for Aleister & Adolf?

Douglas Rushkoff: It’s almost easier to ask where didn’t I find inspiration for Aleister & Adolf. The moment it occurred to me was when I was in an editorial meeting at DC/Vertigo about my comic book Testament, back in 2005. The editor warned me that there was an arcane house rule against having Jesus Christ and a Superhero in the same panel. Not that I was going to get to Jesus in my story, but the rule got me thinking about other potentially blasphemous superhero/supervillain pairings. And that’s when I first got to wondering about Aleister Crowley vs. Adolf Hitler.

But as I considered the possibility, it occurred to me that they were practicing competing forms of magic at the same time. And then I began to do the research, and learned that the premise of my story was true: Aleister Crowley performed counter-sigils to Hitler’s. Crowley came up with the V for Victory sigil that Churchill used to flash—and got it to him through Ian Fleming (the James Bond author) who was MI5 at the time.

I’ve always wanted to do something about Crowley, but I’ve been afraid for a bunch of reasons. Making him something of a war hero, and contrasting him with a true villain like Hitler, became a way to depict him as something more dimensional than “the Beast.”

Did you think of the ending first? It’s a bit like a punchline, isn’t it?

Douglas Rushkoff: I didn’t think of the ending first. The first thing I thought of was to have a young American military photographer get sent to enlist Crowley in the magical effort. I wanted us to see the story through someone like us—someone more cynical, perhaps—and then get to have the vicarious thrill of being drawn into Crowley’s world.

Then, I decided I needed a framing story – just to show how relevant all this creation of sigils is to our world today. So I created a prologue for the story, that takes place in a modern advertising agency: the place where the equivalent of sigil magic is practiced today. I wanted to set the telling of the story within the frame of how corporate sigils are taking life on the Internet today. So the outer frame takes place in the mid-90’s, when the net was being turned over to marketers. The ending is pretty well broadcast up front.

Aleister & Adolph reminds me a lot of Robert Anton Wilson’s Masks of the Illuminatus—which I think is his best book—because it sort of forces its ideas into the reader’s head like an earworm that you can’t resist. Also Crowley is a character in that book, too, of course. Do you see it as a bit of a RAW homage?

Douglas Rushkoff: It’s a RAW homage in that the story has verisimilitude—it is told in a way where it’s absolutely possible for this all to happen. There’s no supernatural magic here; it’s just the magick of Will. There’s the black magic of the Nazis. But however extreme the Nazis, it was real. It’s got the reality quotient of Eyes Wide Shutor Apocalypse Now.

And that’s the understanding of sigil magic I got from Bob. It’s all very normal. That doesn’t mean it doesn’t work. Just that you have to participate in its perception. It’s just a different way of understanding the connections. So while the protagonist of the story starts off as a disillusioned atheist and ends up believing in magick as Magic, even Crowley (at least my Crowley) tries to convince him not to take it so literally.

I wouldn’t understand magick that way if it weren’t for Bob. It’s embedded in the fabric of reality. It doesn’t need to break the rules of reality to work.

Are you aware of a recent trend among some alt-right types to organize acts of group 4Chan “meme magick”? Some of it’s just blatant harassment and bullying over Twitter, but there’s actually a sophisticated intent behind some of it. Pepe the Frog has become a hypersigil. I’m not being admiring of it—the idea that certain reichwingers would want start a magical war via social media is alarming to say the least—but the concept is a sound one magically speaking: They’ve figured out how to amplify their signal’s strength like a radio transmitter.

Douglas Rushkoff: There’s a real crossover between the alt-right and the occult. I knew a guy writing a book about it, in fact. And remember, it was one of Bush’s advisors who once explained that the future is something you create. And there’s an any-means-necessary quality to libertarianism that is consonant with chaos magic.

Plus, you’re talking about homespun propagandists inhabiting the comments sections of blogs and things. They’re not reading Bernays and Lippman. They’re waging hand-to-hand battle in the ideological trenches. A bit of NLP, rhetoric, and magic are what you turn to.

The interesting thing here is why the left does not use these techniques. It goes against our sense of what is fair. We know we’re “right” and so we want to win with the fact. Sigil magic feels like cheating on some level. So we have to ask ourselves, isn’t the full expression of our Will something we want to unleash? If not, why not?

This isn’t the freethinking/pansexual “Generation Hex” types who seemed to be on the horizon a few years ago, but rather like an evil skinheads contingent at Hogwart’s.

Douglas Rushkoff: Alas it is not. That’s partly because the freethinking pansexuals got a bit distracted by other things. And most of them worked alone. I don’t think there were nearly as many, either. That’s pretty rarified air. Back in the 80’s, there were more kids taking acid in the parking lot at AC/DC concerts than there were in the dorms of Reid College. And likewise – as a result of economics as much as anything – there’s more gamergaters throwing sigils online than Bernie Sanders supporters. Sometimes magic gets in the hands of people you’d rather not find it.

Photo of Douglas Rushkoff by Jeff Newelt

Posted by Richard Metzger at http://dangerousminds.net/comments/al...

The post Dangerous Minds Interview: appeared first on Rushkoff.

November 11, 2016

The Sustainability Agenda – How the Digital Revolution Undermines Sustainability

Listen to this interview at The Sustainability Agenda

Author, media theorist, professor, activist: Douglas Rushkoff wears many hats. At the heart of his work is a recurring theme: how to redevelop society to better serve humans. In this episode, Douglas discusses his latest book, Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, which raises fundamental questions about what he calls the “old extractive, growth-based capitalism.” This is a hard-hitting critique of the digital revolution, finance in Silicon Valley, and its obsession with growth-and a call for new economic, technological, and social programs to create a fairer, more sustainable economy for humans.

The post The Sustainability Agenda – How the Digital Revolution Undermines Sustainability appeared first on Rushkoff.

November 7, 2016

Inc. – What Twitter, Google, and Politics Have in Common

Read this interview at Inc.com

By Helaine Olen

When Americans go to the polls next week, they will be finalizing an electoral cycle characterized largely by resentment–and Doug Rushkoff, for one, mostly blames the changes spawned by the internet.

Instead of the once-promised glorious new age, one that would free us from the tyranny of the corporate state, we got income inequality, the housing bubble, increased corporate power, and, now, a presidential election like none other in our history. And Rushkoff, a longtime media theorist and author, says the tech industry is partly responsible.

The problem, he says, is not the digital economy itself, but the fact that it adopted an economic model that no longer works. “The conflict here is not really between the 99 percent and the 1 percent. It’s not even stressed out employees against the companies they work for or the unemployed against Wall Street so much as everyone–humanity itself–against a program that promotes growth above all else,” he writes in his most recent book, Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus: How Growth Became the Enemy of Prosperity. (The title is a reference to San Francisco protests in 2013 and 2014.)

I recently reached out to Rushkoff to discuss the book and how the economic problems he identifies are playing out in both politics and private business–including at Google and the currently much-beleaguered Twitter. (This Q&A has been edited and condensed for clarity. And in the interests of full disclosure, Rushkoff mentioned my book Pound Foolish, which he blurbed, in Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus.)

You write about Twitter’s problems in your book. What has it done wrong?

I feel like I’m watching the slow death of Twitter. I liked Twitter because it’s super simple. It’s an utterly transparent, easy-to-understand messaging system. People that subscribe to me see my messages in their feed. It isn’t asking anything of me. Every once in a while there was an ad in the feed. I knew what it was. They are making money off this service. This is good. Everybody’s happy, right?

It turns out no. There’s not room for that. Wall Street right now considers Twitter an abject failure because it turns out that they can’t figure out how a 140-character messaging app can make more than $2 billion a year. That’s not the way to make money with a company like that, a company that has a great sustainable revenue stream. Twitter could last a long time as a $2-billion-a-year business. It’s not allowed to because the investors want home runs. They want 100 times that. They want $200 billion dollars a year or bust. A single or a double’s not possible.

Why does your book throw metaphorical rocks at Google?

At first, Google represented the good guys. There were two kids in their Stanford dorm room who were going to take down Yahoo, which was the big Wall Street company. Now, Google has become not only one of the biggest companies in the world, but now even a holding company. They’re appropriated the sharing, good-for-the-world ethos of San Francisco as a brand image, while actually working against all of those values.

You think Google fell victim to something you call the growth trap. Can you explain that?

One day they took too much money. What if Google had grown a little bit slower, but then got to stay one of the good guys? It would have been way better. There’s no reason to grow that much, but that’s really the growth trap.

When you talk to the CEO of a Fortune 100 company, they’ll say, “My shareholders are demanding 7.2 percent growth this year. The only way I’m going to be able to show that growth is by selling off one of my productive assets. It’s like amputating one of my good arms in order to show growth on the balance sheet or by firing 10,000 competent employees.” What the CEOs are realizing is that the long-term sustainability of their companies, or the long-term sustainability of the markets on which those companies are relying, is being surrendered to show growth because that’s the prime, core command of the economy for the last 700 years.

Our economy is doing exactly what it was programmed to. It’s just that when you do this, on digital steroids, it starts happening in more extreme ways. That slow suck that sometimes people and nations were able to recover from now is a super-fast suck that we don’t know how to deal with.

So what do we need to do instead?

What I’m talking about is pre-distributing the means of production before the fact. What does that look like? Take WinCo, the West Coast chain that’s eating Walmart’s lunch. It’s the same business model as Walmart, except the workers are the shareholders. The workers are paid more. They own the company. They treat their regions differently because they live in the towns where they’re working and they own the company that’s impacting their towns. They have just as good prices as Walmart and so they beat Walmart. They have better customer service and better employee retention. That’s distributive.

How do you convince nascent companies to go along with this?

You have to show people that the probability of having a total monopoly unicorn business is very low. It’s 1 out of 100,000 that you will get to be Facebook, Google, or Exxon. It’s really hard to be one of those. I think more people are looking at that and saying, “You know? Fifty million dollars is not so bad. No, I won’t get to go to certain parties and I won’t get on the cover of certain magazines, but I’ll have $50 million.”

Right, but all we see are the companies and people who won the lottery, as you put it. How do we convince people to change when that’s the model?

I recently went to Silicon Valley, and I was trying to argue to young developers that tens of millions of dollars as your exit is enough. Be happy with that. But there’s a certain ego thing. They want to be Mark Zuckerberg. They want everyone to know who they are. On the other hand, there are a lot of people out there that are realizing being a millionaire and working for a living is more fun than trying to be a multi-billionaire and never working. They’re kind of seeing that.

Basically, if you set your sights–and I hate to call it lower, but let’s call it that–if you set your sights lower, you’ve got a company. God bless. You should be really happy with that. It’s partly the digital culture that makes you need to have 10 million followers. You have to be Elon Musk or Travis Kalanick in order to feel OK about yourself.

There are ways to do it. You just have to think about doing it small rather than at large scale or by creating a community of people who share in the value creations. Patagonia did by going private. Michael Dell did by going private so he could retake control of his company. His name is on it. It’s a family business in a certain way, so he wants to think about how can this business survive rather than not.

Once you take a lot of money, your investors will insist that you hit a home run. That means that you pivot away from your very viable and highly probable, profitable business strategy and adopt instead a scorched earth one-in-a-million unicorn strategy.

How is this all playing out in the politics of 2016?

People do have a sense that the system itself is rigged against them. That something is wrong and it’s wrong on a fundamental level. It’s depending on the operating system that’s killing us all. They get that an establishment candidate in one way or another is going to be supporting this existing system. What many of them want, just like the people who are throwing rocks at the Google bus, is someone to break the thing. Donald Trump, if nothing else, is consummate with the digital media environment. He’s an internet troll manifesting in the real world. He’s born of the angry comment section after any article.

The post Inc. – What Twitter, Google, and Politics Have in Common appeared first on Rushkoff.