Ronald E. Yates's Blog, page 52

June 16, 2021

AOC: The Queen of Dumb People in Congress

Today, I am reposting a recent article by author and actor Michael Knowles, who also hosts the Daily Wire’s The Michael Knowles Show.

In his article, Knowles discusses how sadly ill-informed American Millennials, such as Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, are when it comes to such critical topics as economics, socialism, capitalism, and America’s system of representative government, otherwise known as a Republic.

The ignoramus leading the harebrained charge of the grossly oblivious is Democrat Congresswoman Ocasio-Cortez, of New York. AOC, as she is now referred to, apparently slept through all of her college classes on economics, civics, and the history of such homicidal socialist despots as Lenin, Stalin, Mao, Kim Jung Il, Fidel Castro, and Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu.

Otherwise, it defies logic to understand how Ocasio-Cortez can propose such loopy ideas as the Green New Deal and her foolish campaign in 2019 to oppose Amazon’s proposal to open a second headquarters in Long Island City, Queens. Because of the hostility of AOC and a few other obtuse socialists, Amazon backed out of an agreement that would have created 25,000 to 40,000 badly needed jobs and, according to NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio, would have added some $27.5 billion to city and state coffers over a 25 year period.

One can only hope that once AOC’s naïve fanaticism wears thin on the more rational and moderate members of the Democrat Party that she will be consigned to America’s growing scrapheap of like-minded crackbrains.

Here then is Knowles’ commentary. Enjoy it or weep. The choice is yours.

By Michael Knowles

The majority of American Millennials identify as socialist, according to surveys by both Reason-Rupe and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. That’s the bad news. The good news is that just 32 percent of Millennials can define socialism.

The frequently wrong but never-in-doubt freshman Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, D-N.Y., may indeed be the voice of her ignorant generation.

During an interview on CBS’s “60 Minutes,” Anderson Cooper asked Ocasio-Cortez, “When people hear the word socialism, they think Soviet Union, Cuba, Venezuela. Is that what you have in mind?” He neglected to mention the vicious socialist regimes of Cambodia, Ethiopia, Poland, Romania, North Korea, and China, among others.

Ocasio-Cortez retorted, “Of course not. What we have in mind—and what of my—and my policies most closely resemble what we see in the U.K., in Norway, in Finland, in Sweden.” In fact, her economic proposals bear little resemblance to British and Nordic public policy.

Alexandria “Crackbrain” Ocasio-Cortez

Alexandria “Crackbrain” Ocasio-CortezAs early as the 1950s, Britain began to privatize its social security and pension programs. By the 1990s, as decades of socialism caused economic growth to stagnate, Sweden followed suit. Neither Sweden nor Norway mandates a minimum wage, and Britain demands a minimum wage well below Ocasio-Cortez’s proposed $15 per hour.

Britain and Finland offer a lower corporate tax rate than the United States, and all the nations she names have lower rates than her proposal of 28 percent. None has a health care regime as socialistic as her proposed Medicare-for-all scheme, which constitutes a full federal takeover of health care.

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s ignorance of economics and foreign affairs typifies her generation. Despite holding expensive degrees in both Economics and International Relations from Boston University, Ocasio-Cortez threw up her hands in exasperation during an interview on Margaret Hoover’s “Firing Line” program, laughing, “I’m not the expert on geopolitics.”

Fortunately for her, in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king; and among a blithely ignorant generation, the lightly educated activist is a congresswoman.

The seed of Millennial miseducation, which grew into the Tree of the Lack of Knowledge as activist educators substituted ideology for the scholarship, is finally bearing its rotten fruit. According to one survey, one-third of Millennials believe President George W. Bush killed more people than Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.

Over 40 percent of Millennials have never heard of Mao Zedong; another 40 percent and 30 percent, respectively, are unfamiliar with Vladimir Lenin and Che Guevara. Two-thirds of Millennials cannot identify Auschwitz, and 22 percent have never heard of the Holocaust, twice the percentage of American adults on average.

Millennials might not know much, but according to a 2016 Harvard survey, they know they don’t support capitalism, with 51 percent of young adults rejecting economic freedom.

During the 2018 midterm elections, the Democratic Socialists of America endorsed 42 candidates for local, state, and federal office across 20 states. Of those candidates, 24 won their primary campaigns, and 18 won in general elections. Millennials have largely cheered them on.

Raised in the United States after the fall of the Berlin Wall, these young Americans have been sheltered both empirically and academically from the myriad horrors wrought by socialism throughout history. And so the problem worsens.

Socialism is an economic disease born of envy and ignorance. Unfortunately, both abound in our present politics. The sickness has found an attractive spokeswoman—perhaps, sadly, the voice of her generation.

Michael Knowles is an author, actor, and hosts “The Michael Knowles Show” at the Daily Wire. Follow him on Twitter @michaeljknowles

June 15, 2021

Two Tales about the Catastrophe called Socialism

We are hearing a lot today about the alleged advantages of socialism over the capitalist system that has been the main engine of wealth in the United States and the world.

Thousands of teachers in K-12 schools, university professors, and a growing number of Democrats in Congress are singing socialism’s praises, along with such half-baked Marxist ideas as Critical Race Theory and the 1619 Project, both of which a majority of historians have refuted and nullified as racist gibberish. #DefundCRT

Yet the socialist beat goes on, pushed by Black Lives Matter, Antifa, and other felonious, semi-terrorist organizations.

In my post today, I am not going to argue against this failed system of government. I will let a couple of stories—one true and one perhaps apocryphal (though I have heard it is true)–help you decide for yourself if socialism is right for America.

But before I do, I will share a couple of thoughts about socialism with you.

The first comes from the American economist and social theorist Thomas Sowell, who is a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell“Socialism, in general, has a record of failure so blatant that only an intellectual could ignore or evade it,” Sowell has said.

The other is a rather simple definition of socialism. It comes from a variety of anonymous sources, with annotation from yours truly.

Here’s the way capitalism works. You buy a pizza and sell the slices for a profit to others who want pizza. Here’s the way socialism works. You and others are forced to share a pizza when you really want a hamburger. (Sorry AOC, you will never stop me from eating an In-And-Out Burger no matter how much you yammer on about livestock flatulence).

Okay. Here’s the first socialist tale.

A few years ago, an economics professor at a Texas university said he had never before failed a single student but that he had, once, failed an entire class.

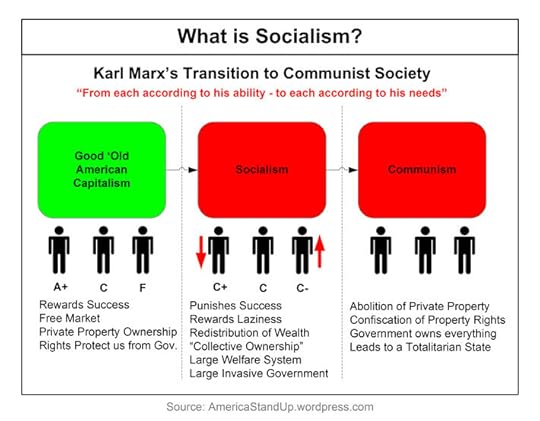

During a discussion of economic and political systems, the class had insisted that socialism worked—that it was the great equalizer in which no one would be poor and no one would be rich.

The professor tried to disabuse them of that notion and when he failed, he said OK, if everybody agrees, we’re going to have a practical experiment on socialism in class.

Here is what he proposed: All grades would be averaged and everyone would receive the same grade so that no one individual would fail and no one individual would receive an “A.” Everyone in the class would receive the same grade.

After the first test, the grades were averaged and everyone got a “B.”

The students who studied hard were upset and the students who studied little were happy. But, as the second test rolled around, the students who studied little studied even less, and the ones who studied hard decided they wanted a free ride too, so they studied very little. The second test average was a “D!”

No one was happy. When the third test rolled around the average was an “F.”

The scores never increased as bickering, blame, and name-calling all resulted in hard feelings. No one would study for the benefit of anyone else.

To nobody’s surprise, everyone failed. Naturally, the class was not happy.

It was a powerful teaching moment and the professor used it to show the class that socialism ultimately always fails because when the reward is great, the effort to succeed is great; but when the government (i.e. the professor) takes the reward away there is no incentive work hard or to succeed.

Couldn’t be any simpler than that.

Now, to the true story of socialist theory in action.

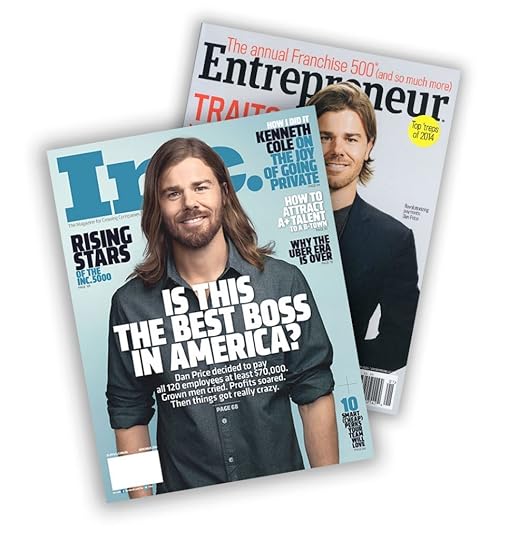

Think back to 2015 and you may remember the story about a 10-year-old Seattle-based company called Gravity Payments, and the decision by its CEO to pay all of his 120 employees the same minimum salary of $70,000.

Financial analysts hailed the “groundbreaking” move while the left-leaning media praised Dan Price, the CEO of the credit card payment firm, for taking a $930,000 pay cut so he would earn the same $70,000 as the rest of his employees.

CEO Dan Price

CEO Dan Price Socialists everywhere were giddy over what they called a “victory” in the fight to erase income inequality. From the outside looking in, that’s what Price’s socialist experiment looked like.

As the dust began to settle, it seemed like business as usual for Gravity Payments, but as it turned out, all was not well in the workforce. Staffers began to question why lesser-qualified employees with fewer responsibilities were making the same money they were. (Ahem, remember that Texas Tech professor and his students?)

What a shock! High achievers complained that people making the same salary as they were “clocking in and clocking out” as usual, while those in higher positions within the company stayed late to get their jobs done.

“It’s unfair,” they groused.

Who would have thought it? And it wasn’t just the staff that grew unhappy. Clients canceled contracts because they decided Price’s $70,000 stunt was nothing more than that—a stunt. Some saw it as a misguided political move to embrace socialism, while others didn’t want to be associated with a company that treated highly skilled employees “unfairly.”

Sure, the company wallowed in a tsunami of publicity from a besotted left-leaning media. It was inundated with new client applications and, as expected, a flood of job applications poured in from those eager to earn $70,000 a year. What a deal.

Think about it if you are an ambitious young man or woman. You work your way through college. You study hard, make good grades and eventually, you leave with a costly degree that will give you a jump start in the callous, cutthroat world. At work, you spend a few years paying your dues. You learn how to listen, how to work alongside your peers, and how to ascend the career ladder. You feel like all your hard work has finally been worth it. You are on a successful career path.

The same goes for those who do not go to college. You’ve worked hard, gained valuable experience in your chosen field, and ascended the same ladder as your college-educated peers. You see success ahead. Then, one day, the company you work for pulls this stunt.

Before you know it, Wanda the receptionist, and Willard, who is fresh out of school and who only started at the company last month, are getting the same salary as you are.

Suddenly, that fantastic working environment you’re used to is satiated with bitterness. People are unhappy. When people are unhappy, performance wanes. Soon, the best workers leave for companies that they know will reward them for their talent and work. Then, what was a great company to work for with great client reviews, is a sinking ship.

A sinking ship is a perfect metaphor for the disaster called socialism. If the United States moves toward that doomed system, there won’t be enough life rafts to go around.

But if the well-documented failure of socialism tells us anything, you better believe those at the top of the collectivist heap will be safely onshore.

Click on the link below for a short but insightful lesson from a successful CEO about the differences between socialism and capitalism.

June 14, 2021

Today is Flag Day. Some Facts About this Misunderstood Holiday

Flag Day

Today is Flag Day. Big deal, you might say. Who cares? And anyway, just what is it and why is it considered a holiday, albeit a minor one?

Here is a little history about Flag Day along with 13 surprising facts about the American flag and how to properly display it—which I sincerely hope all of you reading this post, will do.

What follows comes from the History Channel (one of my favorite satellite TV haunts).

When the American Revolution broke out in 1775, the colonists weren’t fighting united under a single flag. Instead, most regiments participating in the war for independence against the British fought under their own flags. In June of 1775, the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to create the Continental Army—a unified colonial fighting force—with the hopes of more organized battle against its colonial oppressors. This led to the creation of what was, essentially, the first “American” flag, the Continental Colors.

For some, this flag, which was comprised of 13 red and white alternating stripes and a Union Jack in the corner, was too similar to that of the British. George Washington soon realized that flying a flag that was even remotely close to the British flag was not a great confidence-builder for the revolutionary effort, so he turned his efforts towards creating a new symbol of freedom for the soon-to-be fledgling nation.

On June 14, 1777, the Second Continental Congress took a break from writing the Articles of Confederation and passed a resolution stating that “the flag of the United States be 13 stripes, alternate red and white,” and that “the union be 13 stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

More than 100 years later, in 1916, President Woodrow Wilson marked the anniversary of that decree by officially establishing June 14 as Flag Day. As you celebrate the anniversary of the Stars and Stripes, here are some fast facts about “Old Glory.”

Bernard Cigrand, a small-town Wisconsin teacher, originated the idea for an annual flag day, to be celebrated across the country every June 14, in 1885. That year, he led his school in the first formal observance of the holiday. Cigrand, who later changed careers and practiced dentistry in Illinois, continued to promote his concept and advocate respect for the flag throughout his life.It is widely believed that Betsy Ross, who assisted the Revolutionary War effort by repairing uniforms and sewing tents, made and helped design the first American flag. However, there is no historical evidence that she contributed to Old Glory’s creation. It was not until her grandson William Canby held an 1870 press conference to recount the story that the American public learned of her possible role.The lyrics of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” America’s national anthem since 1931, are taken from a patriotic poem written by Francis Scott Key after he witnessed the Battle of Fort McHenry during the War of 1812. His words were set to the tune of “To Anacreon in Heaven,” a popular British drinking song.In the 1950s, when it seemed certain that Alaska would be admitted to the Union, designers began retooling the American flag to add a 49th star to the existing 48. Meanwhile, a 17-year-old Ohio student named Bob Heft borrowed his mother’s sewing machine, disassembled his family’s 48-star flag and stitched on 50 stars in a proportional pattern. He handed in his creation to his history teacher for a class project, explaining that he expected Hawaii would soon achieve statehood as well. Heft also sent the flag to his congressman, Walter Moeller, who presented it to President Eisenhower after both new states joined the Union. Eisenhower selected Heft’s design, and on July 4, 1960, the president and the high school student stood together as the 50-star flag was raised for the first time. Heft’s teacher promptly changed his grade from a B- to an A.Unlike setting an intact flag on fire, flying one upside-down is not always intended as an act of protest. According to the Flag Code, it can also be an official distress signal.The Flag Code stipulates that the Stars and Stripes should not be used as apparel, bedding, or drapery.The practice of draping coffins in the American flag is not reserved for military veterans and government officials. On the contrary, any burial may incorporate this tradition.Etiquette calls for American flags to be illuminated by sunlight or another light source while on display.During the Vietnam War era, some demonstrators burned American flags as an act of protest. The Flag Protection Act of 1968 was enacted in response, making it illegal to burn or otherwise deface the Stars and Stripes. In two landmark decisions 20 years later, the Supreme Court ruled that the government couldn’t curb individuals’ First Amendment rights by prohibiting desecration of the U.S. flag. Respectful burning of damaged flags according to established protocol has always been acceptable.When flags are taken down from their poles, care must be taken to keep them from touching the ground. In fact, the American flag should always be kept aloft, meaning that rugs and carpets featuring the Stars and Stripes are barred by the Flag Code.When the flags of cities, states, localities or groups are flown on the same staff as the American flag, Old Glory should always be at the peak. When flags of two or more nations are displayed, they should be of equivalent size and flown from separate staffs of the same height.The Flag Code strictly prohibits adding an insignia, drawing or other markings to the Stars and Stripes. Some American politicians have been known to defy this regulation by signing copies of the U.S. flag for their supporters.Ever wondered how to correctly fold an American flag? First, enlist a partner and stand facing each other, each holding both corners of one of the rectangle’s shorter sides. Working together, lift the half of the flag that usually hangs on the bottom over the half that contains the blue field of stars. Next, fold the flag lengthwise a second time so that the stars are visible on the outside. Make a triangular fold at the striped end, bringing one corner up to meet the top edge. Continue to fold the flag in this manner until only a triangle of star-studded blue can be seen.Below is a short video of the song “Stars and Stripes Forever.” Enjoy

June 13, 2021

A Message to ForeignCorrespondent Subscribers, Friends, and Visitors

Dear subscribers and friends of ForeignCorrespondent,

Some of you may have already seen this message, and if you have, we apologize for the recurrence.

Others may not have seen the message but may have noticed a few changes on our blog in the past two weeks or so.

Here’s what has happened.

We have simplified the method by which you can comment on posts. In the past, you were required to comment through the Facebook interface. That is no longer the case.

Now, all you have to do is register by creating a free account. You do that by clicking on the red “Create a Free Account” link at the bottom of every post, such as this one.

This is a ONE TIME exercise. Once you have created an account, you are automatically registered as a subscriber/member of the growing ForeignCorrespondent community and can comment quickly and easily. After creating a free account, you will receive two emails—one welcoming you to ForeignCorrespondent and a second one asking you to verify your email address.

Once your email address is confirmed, you will receive a third email confirming that. You can then log in to ForeignCorrespondent using your newly created login and password. NOTE: Watch for these emails, and if you don’t see them in your inbox, please check your spam folder. Also, you may want to refresh or clear your cache, especially if you’ve visited ForeignCorrespondent before these changes.

The folks who administer ForeignCorrespondent and keep it running smoothly created a short silent video demonstrating the sign-up process. When you click on the link, you will see a sample email inbox on the left of the screen. On the right side of the screen, you will see the ForeignCorrespondent website. The video shows you in real-time how to create an account and what happens next.

https://productadvancecloud.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/ronaldyates/ronald-yates-signup.mp4

Finally, if you go to the main page of the ronaldyatesbooks.com website, in addition to a couple of book trailers, you will see under the heading “The Latest From My Blog” short previews of twelve of our most recent blog posts. Just click on any of these, and it will take you to the ForeignCorrespondent Blog page, where you can read the post you ticked.

That’s it. It may seem complicated, but really it isn’t. This process makes commenting much easier while protecting the site (and you) from hackers, spammers, bots, and other attacks.

IMPORTANT! We welcome ALL COMMENTS and DISCUSSIONS. Unlike Big Tech and their censor-happy social media tyrants, ForeignCorrespondent is a blog that encourages the exchange of ideas and opinions–the more, the better. So don’t be shy. Let it fly.

And as always, please feel free to share any of our posts or content with your friends or the public.

Cheers!

Ron Yates

June 12, 2021

A Few Meditations on Writing

I have been writing, in one form or another, for most of my life. I learned the techniques and skills of writing by toiling for almost 30 years in the relentless and stressful world of journalism.

I was in some pretty good company. Ernest Hemingway began his writing career as a journalist. So did Rudyard Kipling, George Orwell, Graham Greene, Charles Dickens, Evelyn Waugh, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, Hunter S. Thompson, Jack London, Annie Proulx, Stephen Crane, John Steinbeck, James Agee, Lillian Ross, and Mark Twain.

For 13 years I taught writing and reporting at the University of Illinois after leaving the world of professional journalism. During that time, I managed to condense my thoughts on writing into a structure suitable for the classroom.

So allow me to share my views on writing.

Writing is both an art and a craft. To be a good writer you must first master the tools of the craft. What are those? They are vocabulary, grammar, research, style, plot, pacing, and story.

Words are your basic tools. They are your implements in the same way hammers, saws, bubble levels, squares, screwdrivers, and tape measures are the tools a carpenter must possess.

Then comes grammar. Just as carpenters must learn to respect and skillfully master their tools, so too must writers learn to skillfully manipulate words and respect the language.

If you don’t respect the language, you will never succeed as a writer.

You must also give yourself time to learn the art and craft of writing. You don’t learn how to be a writer by sitting alone in a room and squeezing your brain for inspiration the way you wring water from a sponge.

One of the first steps to becoming a good writer is reading. Read, read, and read. As I used to tell my students, “If you want to write well, read well.”

Learn from the best; imitate (and I don’t mean plagiarize). Listen to the words! Words speak to us from the written page, IF we let them IF we allow our eyes to open our inner ears.

Gifted writing can’t be taught. It must be learned.

And we learn from doing it; from experience. That’s how we gain confidence.

Let me repeat that because it is SO VERY IMPORTANT. To be a good writer you need to be confident in your ability to use the tools of the craft: vocabulary, grammar, research, style, plot, pacing, and story.

A confident writer is typically a good writer. We gain confidence by being successful in our work–no matter what work we do. We also learn from failure. Why was a book rejected 40 times? Why isn’t it selling on Amazon or Goodreads or Barnes and Noble? There must be a reason. Find out what it is and learn from it. Then go back to work and make the book better.

Once you master the Craft of Writing…the fundamentals, the mechanics, the “donkey” work, then you are ready to move on to the Art of Writing.

I don’t know if those who do not write for a living understand just how difficult writing is. Many believe that writers work from inspiration and that the words simply leap onto the blank page (or into yawning maul of the computer).

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest HemingwayErnest Hemingway once said: “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”

In fact, while inspiration is a wonderful thing, it is not what makes a good writer or book. Writing requires significant research, whether fiction or non-fiction. It requires a facility for organization and a keen sense of plot, pacing and story.

I don’t believe writers are “born.”

They evolve over time as a result of significant experience in the craft.

Not all writers are brooding, intractable alcoholics, or unbearable misanthropes who feel their creations contain irrevocable and definitive truths that most of humanity is too obtuse to comprehend.

In fact, most successful writers are excellent storytellers and they like nothing more than to have their stories read by as many people as possible–even if those stories don’t always possess immutable truths.

And storytelling is not limited to fiction. Storytelling in non-fiction or journalism is just as important.

When I was young, I used to write lots of short stories. Were they any good? No. But for a person who wants to be a writer they were my way of practicing. Sort of like practicing the piano or the flute or some other instrument. The more you practice, the better and more accomplished you become.

Somerset Maugham, the author of such classics as The Razor’s Edge, The Moon and Sixpence, and Of Human Bondage, had this to say about writing: “If you can tell stories, create characters, devise incidents, and have sincerity and passion, it doesn’t matter a damn how you write.”

June 11, 2021

America, the Neo-Tribal Nation

It is unsettling and sad to witness what is happening in our great country today.

Never in my lifetime—and I’m older than Methuselah in dog years—have I ever witnessed such a sprint to socialism by an occupant of the White House.

What bothers me about Joe Biden’s distressing embrace of socialism, is how compliant the left is in its capitulation to an ideology and form of government that has failed in every nation it has been instituted. Just as disconcerting is Biden’s acquiescence of identity politics rather than the rational and intelligent liberal ideology that once defined the Democrat party.

When I was young, what attracted me to the Democrat party was its issue-oriented, logical approach to dealing with the nation’s social and economic problems. I can still remember a time when voting for a Democrat didn’t mean you were embracing socialism and, by definition, extreme loathing and disgust for anybody who was not a Democrat.

Sadly, those days are gone, given the Democrat party’s apparent embrace of socialism and identity politics.

What do I mean by identity politics?

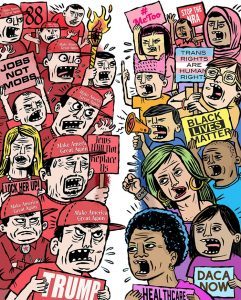

It means that each of us belongs to a sub-group defined by race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, etc. Let’s look at the behavior of the Democrat Party in the last couple of Presidential elections. Instead of focusing on broad issues such as jobs and income growth, Democrats catered to members of different sub-groups, promising to give them power.

Did Hillary Clinton offer the middle class an agenda for which they could vote? No, she catered to sub-groups hoping that they would coalesce enough to send her to victory. It didn’t work.

Unfortunately, Joe Biden is continuing that strategy. In just about every speech he gives, he makes reference to America’s “systemic racism,” white supremacists, and “domestic terrorism” (code for conservatives who support the policies of Donald Trump). He promised to “reunite” the nation and bring people together. Instead, he drives a wedge deeper and deeper into the American psyche, pushing people further apart into their separate and segregated communities.

In essence, what Joe Biden and the Democrats apparently want to divide us into competing tribes, each with its own agenda, its own set of grievances, and its own view of what America should look like.

The problem with that is this: if one or two tribes win, then the others lose. Today’s result is a country that is tearing itself apart, ripping away the very fabric of our nation, and destroying the excellent idea that makes America unique in world history.

Look at what it says on the nation’s Great Seal: “E Pluribus Unum”—Out of Many, One.”

Think about what that means. Out of many peoples, races, religions, languages, and ancestries has emerged a single people and nation.

We used to talk about America being the great melting pot—a fusion of different cultures, ethnicities, and nationalities.

That is no longer politically correct. Today we are taught there is no need to assimilate, to “become an American.” Instead, we each have our own identity: African-American, Mexican-American, Transgender, LGBTQ, Muslim, Evangelical, Jew, Democrat, Republican, etc.

This is neo-tribalism, in which we are identified by what sub-group or tribe to which we belong. We are no longer “Americans.” We are something else, something I no longer recognize.

Many on the left, especially leaders in racially minority communities, talk about the “browning of America” as though it is some holy crusade. The traditional white majority will be relegated to minority status. When that happens, it will be “payback” time for whatever sins and transgressions–real or perceived–that were committed by the nation’s white majorities of the past. If that is indeed the goal of minority gurus and kingpins, we are headed down a dark and dangerous path of disunity, division, and perhaps even violence.

It means instead of thinking about the whole and the many, we will think about ourselves and what sub-group we belong to first and the country last, if at all.

It means that instead of allowing reasonable debate about issues, those who belong to a sub-group JUST WANT TO WIN. Debate is no longer a means to a solution. In their minds, violence, rioting, burning, destroying property, shouting down those who disagree with them, and ignoring freedom of speech is the new modus operandi.

Concepts that we were once taught to respect and cherish, such as freedom of speech, the rule of law, the nuclear family, patriotism, adherence to religion, and belief in God, are under dangerous assault by a profane and secular left.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Marilynne Robinson has said it very well:

“At the outset, we were fortunate to have a group of people write essential documents that gave us a good deal to think about. And I think that a lot of the higher quality of American discourse, when it has been high, is out of respect for the fact that these are valuable things that impose respect for people of other views.

“And, at this point, things have deteriorated to the point that it is morally wrong to have an attitude of presumptive respect toward someone you disagree with. That’s just bizarre, and it’s obviously not a formula for civilized society.”

I am saddened when I hear those on the left say that our Constitution is no longer germane, that our traditions are not noble, that our Bill of Rights is irrelevant, and that we do not live in an exceptional country.

I remember listening to what President John F. Kennedy said during his 1961 inauguration speech. It still resonates with me today. (I saw that speech on TV, and I would have voted for Kennedy were I old enough to vote back then).

“My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

I took those words to heart. I joined the U.S. Army and served four years gathering intelligence for the National Security Agency. Others joined Kennedy’s Peace Corps and went to third-world countries to help people produce clean water, build decent housing, and eliminate illiteracy.

I am proud of my service to this country. I hate seeing it ripped apart today by self-centered politicians, race hustlers, Marxists, socialists, and others who put their political dogmata and themselves before the country, who feel it is acceptable to use a deadly global pandemic to score political points, and who want to use any means possible to cancel and destroy those with whom they disagree.

That is exactly what we saw in 2020 when Democrats howled for Donald Trump’s political lynching—which is what impeachment is.

I hear some political operatives talking about doing the same thing to Joe Biden should Republicans gain control of the House in 2022–and maybe the Senate.

As much as I would love to see Joe Biden shuffle off into obscure retirement in one of his multi-million-dollar homes before he turns the country I love and served into a socialist sewer, the proper way to remove a president from office is with the ballot, not by decree, violence, or a political coup d’état.

Most of all, I hope that the malevolent ogres seeking to divide and control us are exposed for the America-haters they are and are forced to slink back to the grubby lairs from whence they crawled.

June 10, 2021

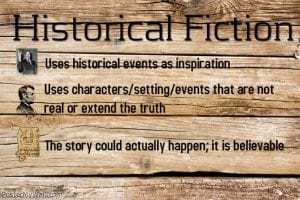

What do you like most about the Historical Fiction genre?

Historical fiction is one of the most popular forms of fiction being written today—along with young adult, zombie apocalypse, romance novels, and sci-fi.

I am specifically interested in learning why people like historical fiction books. I have a few theories, but I would like to know what others think.

As an author, I enjoyed writing the Finding Billy Battles trilogy—a historical fiction trilogy that begins in 19th Century Kansas and then moves (in Book 2) to the colonial Far East, then (in Book 3) to Mexico, and finally back to the United States in the mid-20th Century.

I am interested in knowing what it is that draws a reader (or writer) to this kind of fiction.

As for me, I enjoy doing the research necessary to create an accurate portrayal of the people, places, and events of other eras, such as the 19th Century. I especially like “slowing” down the pace of life from the frenetic and hectic world of the 21st Century.

What I find appealing about eras “BSM” (Before Social Media), smartphones, I-pads, etc. is that you actually had time to THINK rather than simply react.

When I was a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, I can recall telling my office (via telex) when I was covering Vietnam, Cambodia, El Salvador etc. in the 70s & 80s that I would be out of touch for several days.

Then I would go to some remote area and spend time talking with people, analyzing what I was hearing and what I was seeing and then return to write a story that wasn’t filled with “instant wisdom” as we so often see today with journalists who “parachute” in to a country to cover a story.

Writing about the 19th Century, as I did in my trilogy, allowed me to slow down the pace, provide historical context, and give my characters time to think.

Today, we are all in such a hurry to do things, to pack in as much as we can in a single day. When I think about my characters in the Finding Billy Battles trilogy, I envy the fact that they were not sped up by “galloping technology” as we are so often today.

My characters actually had time to stop and smell the flowers, enjoy a brilliant sunset, “listen” to a forest, and take the time to read a good book.

So, I am asking you to tell ME what YOU think about all of this.

Write as much or as little as you like.

I would love to share your thoughts and comments with my followers.

June 9, 2021

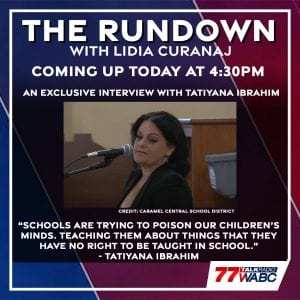

Note to Marxists & Critical Race Theorists: Beware of the Lioness of Carmel

If you haven’t yet met Tatiana Ibrahim, let me introduce her because I can guarantee you that our corrupt leftist news media will not.

Ms. Ibrahim is a mother of a high school-age daughter who finally had enough of the racist and dishonest anti-white garbage children in her town were being indoctrinated with.

So she decided to do something about it. What did she do?

She attended a meeting of her school board to protest teachers in her school district who are bringing Marxism to the classroom in Critical Race Theory.

She also objected to teachers using Marxist Black Lives Matter propaganda in the classroom that call all police evil and, therefore, need to be defunded.

For 11 minutes Tatiana Ibrahim stood at the microphone and condemned a bucket-load of other socialist/communist notions that are being rammed down the throats of Carmel’s children.

When members of the board tried to silence her, she refused to stop talking, and she even “outed” two teachers who had publicly posted CRT, BLM, and Marxist dogma they are teaching K-12 children.

Ms. Ibrahim is not alone in her outrage. Because of the year-long COVID-19 lockdowns and the resulting distance learning that children were forced to endure, parents had a unique window into the nation’s classrooms. They saw for themselves the racially divisive messages with which teachers were brainwashing their children.

As a result, more and more exasperated parents are attending school board meetings and sending open letters to schools to protest the socialist/Marxist garbage that is the core of CRT and the deceitful history contained in the 1619 Project.

I have seen a few videos of those parents addressing school boards. In some cases, those parents were shouted down by board members and even escorted out of the meeting. Some teachers who have dared speak out about the destructive Marxist curricula being taught to children have been suspended or even lost their jobs for disparaging CRT and BLM dogma.

But a few days ago, when Tatiana Ibrahim stood before the microphone, you could tell this was a woman who was not going to be silenced by anybody. She dominated the room.

She reminded me of news anchor Howard Beale in the 1976 movie “Network” (played by the late Peter Finch), who lets out all of his frustrations of the world before shouting, “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore!” and urges all viewers to open their windows and do the same. (Click the the link below to see that short clip)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MRuS3dxKK9U

I have included the entire video of Ms. Ibrahim’s impressive reproach of the Carmel school board below, but I was disappointed by the passive and silent reaction of the other parents in the room.

I would have expected shouts of “right on, Tatiana,” or “let ’em have it,” or at least some applause or cheering as she made one excellent point after another.

Instead, they just sat there. Maybe they were terrified that the school board would identify them and, by association, also their children—and add them to some clandestine blacklist for future persecution or torment.

Clearly, Tatiana Ibrahim had no such concerns. She let the school board have it.

I hope more parents follow her lead and do the same before our children are irreparably damaged by the socialist/Marxist propaganda being circulated in America’s schools.

Now, please watch Tatiana Ibrahim earn her new appellation and reputation as the “Lioness of Carmel.” You will not be disappointed!

Here’s the link. (Note: FYI, the video pauses at one point early on but resumes a second or two again later).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxu3wdiXRF0

June 8, 2021

A Note to ForeignCorrespondent Subscribers, Friends, and Visitors

Dear subscribers and friends of ForeignCorrespondent.

You may have noticed a few changes on our blog in the past week or so.

Here’s what has happened.

First, we have simplified the method by which you can comment on posts. In the past, you were required to comment through the Facebook interface. That is no longer the case.

Now, all you have to do is register by creating a free account. You do that by clicking on the red “Create a Free Account” link at the bottom of every post, such as this one.

This is a ONE TIME exercise and once you have created an account you are automatically registered as a subscriber/member of the growing ForeignCorrespondent community and can comment quickly and easily. After you create a free account, you will receive two emails—one welcoming you to ForeignCorrespondent and a second one asking you to verify your email address.

Once your email address is confirmed, you will receive a third email confirming that. You can then log in to ForeignCorrespondent using your newly created login and password. NOTE: Watch for these emails and if you don’t see them in your inbox, please check your spam folder in case they wound up there. Also, you may want to refresh or clear your cache, especially if you’ve visited ForeignCorrespondent before these changes.

The folks who administer ForeignCorrespondent and keep it running smoothly created a short video that demonstrates the sign-up process. It is a silent video. When you click on the link you will see a sample email inbox on the left of the screen. On the right side of the screen, you will see the ForeignCorrespondent website. The video shows you in real-time how to create an account and what happens next.

https://productadvancecloud.sfo2.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/ronaldyates/ronald-yates-signup.mp4Finally, if you go to the main page of the ronaldyatesbooks.com website, in addition to a couple of book trailers you will see under the heading “The Latest From My Blog” short previews of twelve of our most recent blog posts. Just click on any of these and you will be taken to the ForeignCorrespondent Blog page where you can read the post you ticked.

That’s it. It may seem complicated, but really it isn’t. This process makes commenting much easier while protecting the site (and you) from hackers, spammers, bots, and other attacks.

As always, please feel free to share any of our posts or content with your friends or the public at large.

Cheers!

Ron Yates

June 7, 2021

Are We Entering America’s “Dark Age?”

There was a time when rational people agreed that there were certain immutable laws of nature that were based on facts, common sense, and verified scientific data.

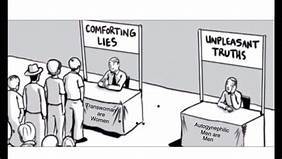

For example, for millennia, humans have known there is a biological difference between men and women. We knew that only women had the physiological ability to become pregnant and give birth. We knew the natural male body is absolutely incapable of becoming pregnant because a simple examination of the bodies of men revealed that there is no birth canal, no ovaries, no uterus.

Gasp! Who knew?

Recently, however, the scientific geniuses at Twitter disagreed. Francisco José Contreras, deputy to Spain’s Vox Party, was locked out of his Twitter account for 12 hours after saying men cannot get pregnant. Contreras had shared a bogus news article, which reported that a “pregnant man” had given birth. “That’s a lie,” Contreras wrote on Twitter about the article. “A man cannot get pregnant. A man has neither uterus nor ovaries.”

For stating a biological fact, Twitter blocked Contreras, claiming his tweet had broken its policies prohibiting “hate, threats, harassment, and/or fomenting violence against people” based on “race, origin, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religion, age, disability, or illness.”

Twitter is not alone in its insanity. Today, thousands of years of proven facts about the physiology of men and women are being cast aside in favor of farfetched fantasies and fabrications by politically motivated quacks and charlatans who insist men and women are physically the same and therefore men, who self-identify as women, should be allowed to compete against natural female athletes. Not even in Europe’s nascent Dark Ages did such an absurd notion gain credence.

A man “identifying” as a 6-foot-8 female basketball player

A man “identifying” as a 6-foot-8 female basketball playerIn the Dark Ages, the enemy of science was religious dogma. Today, the new religion is a blend of leftist radicalism and neo-Marxism that forbids unfettered discussion of most of today’s major questions, such as:

Should biological men and boys who “self-identify” as female be allowed to compete against women and girl athletes?What is the degree of manufactured climate change versus natural, cyclical climate change?When is life established in the womb?Is America a systemically racist nation?Is sex biologically determined or culturally constructed?Why, in an era that is more than one thousand years removed from the outset of the so-called Dark Ages, are purportedly rational people in Congress and the media insisting that there really is NO biological difference between men and women; that gender dissimilarities are a social construct, not a biological fact?

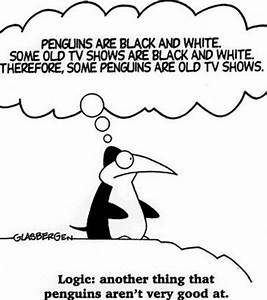

Arguments like that are built on the “fallacy of incomplete evidence,” which refers to the act of pointing to individual cases or data that seem to confirm a particular position while ignoring a significant portion of related cases or data that may contradict that position. It’s a first cousin to the “fallacy of selective attention,” which is commonly called “confirmation bias.” In short, they are as illogical as the syllogism below:

Most commonly, however, these irrational numbskulls resort to the “fallacy of selective use of evidence,” which rejects material unfavorable to an argument. They select data or data sets so that a study or survey will give desired, predictable results which may be misleading or even completely contrary to reality.

Folks, these are the Luddites of our time.

Today, you are likely to be called a social heretic if you insist men and women are physically different. This is thinking straight out of the Dark Ages when scientists like Galileo and Copernicus were viewed as heretics.

I suspect that behind this mind-numbing 21st-century pseudoscience, there is an agenda.

Voila! The announced agenda of those promoting pseudoscience today—primarily far-left zealots, socialists, and assorted Marxists—is to achieve “social justice,” the redistribution of income and wealth, obliteration of the First and Second Amendments (if not the entire Constitution), and the end of what they insist is systemic racism in the United States.

However, the left’s agenda actually is more ominous than that laundry list of objectives.

In essence, what the left is selling amounts to a modern version of feudalism–a self-appointed elite whose status will be maintained by promoting a self-serving socialist one-party rule steeped in neo-Marxist dogma. These “anointed” autocrats will then tell the rest of us peasants how we must live our lives, not unlike the Divine Right of Kings.

It is already happening, and the socialist autocrats are convinced they can get away with cramming such flawed and dishonest concepts as Critical Race Theory, the fraudulent 1619 Project, and even the canard that teaching mathematics and mathematics itself, is somehow racist.

Mathematics racist? Merriam Webster defines mathematics this way:

The abstract science of numbers and their operations, interrelations, combinations, abstractions, space configurations, structure, measurement, transformations, and generalizations. Algebra, arithmetic, calculus, geometry, and trigonometry are branches of mathematics.

Will somebody please explain how something so abstract can be racist?

Here is how some on the left have made that connection. And please excuse this tortured logic.

Math professors at top colleges and universities, including Harvard, Brooklyn College, and even the University of Illinois, where I toiled as a professor and college dean for 13 years, have pontificated that mathematics is rooted in “white supremacist patriarchy” and “white social construct.”

Laurie Rubel, a professor at Brooklyn College, said “the idea of math being culturally neutral is a myth because 2+2=4 reeks of white supremacist patriarchy.”

Say what?

From my earliest days in elementary school, I always thought 2+2=4, nothing more or nothing less. However, it begs the question, is math considered “non-racist” if the mathematical equation were 2-2=1 or 2+2=0?

Rochelle Gutierrez, an education professor at the University of Illinois, insists that math is definitely racist.

“On many levels, mathematics itself operates as “whiteness,” she argues. “Who gets credit for doing and developing mathematics, who is capable in mathematics, and who is seen as part of the mathematical community is generally viewed as “white.”

Gutierrez worries that algebra and geometry perpetuate privilege, fretting that “curricula emphasizing terms like ‘Pythagorean theorem’ and ‘pi’ perpetuate a perception that Greeks and other Europeans largely developed mathematics.”

So THAT’S it, is it? God forbid that white Europeans were somehow involved in the evolution of mathematics as a science. It HAD to be somebody else—preferably somebody with a different skin hue—that ACTUALLY developed mathematical theories and allowed mathematics to develop into a major course of study.

Well, guess what? A good deal of math was developed or improved, or passed on to us today by Greeks and Europeans. Is there something wrong with that? Are we not allowed by the PC Police to acknowledge that fact, the same way we tip our hats to brown and black Arabs each time we say the Arabic word “algebra,” even though algebra predated its modern Arab invention by several thousand years.

Folks, this is nothing more than leftist political correctness run amok.

There was a time when we accepted common sense about how the world worked according to logical, scientific, and, yes, mathematical principles. That assumption defined us as “enlightened” rather than Dark Age reductionists and ideological, myth-driven zealots.

No longer, it seems. Leftists, especially those who have hijacked our media, are most often regressive, anti-Enlightenment, and intolerant people, who start with a deductive premise and then make the evidence conform to it—or else.

Remember the “fallacy of selective use of evidence?”

Welcome to America’s Dark Ages—an Orwellian world where up is down, the sun circles the earth, hot is cold, war is peace, success is failure, mathematics is racist, boys are really girls and vice versa, and roosters crow before sunrise and, therefore, cause the sun to rise.

My question is this: will intelligent Americans allow themselves to be led like sheep to the paradoxical slaughterhouse for the half-baked?

Or will they finally say:

“Enough is enough, men are NOT women, and therefore men should not be allowed to compete against women in sporting events,”

OR

“Critical Race Theory is B.S. and so is the 1619 Project; mathematics is NOT racist, and America is not a systemically racist nation.”

OR

“Our 21st-century Luddites will not drag rational Americans into a new Dark Age where the government is the master of the people; where leftist/socialist politicians and their lackeys in the bureaucracy will determine who the winners and losers are, and where everyone must submit to the government or be canceled–a synonym today for being socially and politically annihilated.

Invictus maneo!