Ronald E. Yates's Blog, page 48

August 20, 2021

When Does A Gap Become a Canyon? (Part 1)

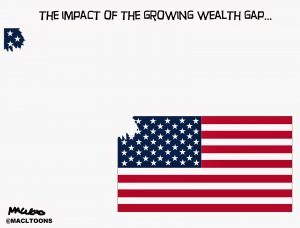

In the past few weeks, two stories caught my attention. One decried the growing wealth gap between the young and old in America. The other highlighted the growing difference between older and younger Americans on issues such as social values and morality.

Should we be surprised by either of these stories?

I think not.

Let’s look at the wealth gap first. I will get to the Social Values and Morality Gap in Part 2.

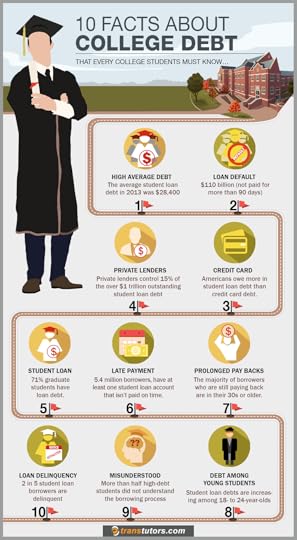

A report issued by the U.S. Census Bureau said the wealth gap between younger and older Americans has increased to the widest on record, worsened by a prolonged economic downturn that has wiped out job opportunities for young adults and saddled them with housing, credit card, and college debt.

The typical U.S. household headed by a person age 65 or older has a net worth 47 times greater than a household headed by someone under 35, the report said, adding that the gap in wealth is now more than double what it was in 2005 and nearly five times the 10-to-1 disparity a quarter-century ago, after adjusting for inflation.

Why is this? Part of it is caused by the economic downturn, which has hit young adults particularly hard. As I saw when I was a Dean at the University of Illinois, more young people are pursuing college or advanced degrees, taking on debt as they wait for the job market to recover. Others are struggling to pay mortgage costs on homes now worth less than when they were bought in the housing boom.

But that is not the whole story. All of us have gone through hard times at one point or another. I can recall when mortgage interest rates were 19 percent and buying a house was simply out of the question. I can recall unemployment rates running between 7 and 9 percent and double-digit inflation–none of which made life much fun.

Perhaps it’s the way many in the so-called silent and baby-boomer generations lived and spent money. Without sounding like some old geezer, I should point out that when I was in my 20s, I didn’t have a credit card. I did have a gasoline charge card from Standard Oil, but the thought of charging meals, groceries, vacations, car repairs, etc. on a credit card was simply not an option. Credit cards were simply not the ubiquitous snares that they are today.

I paid cash for just about everything. I even paid back my student loan–though I was fortunate to have a large part of my college education paid for via the GI Bill.

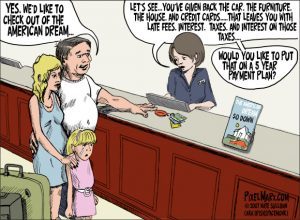

Today, young people are crushed under the weight of credit card debt. Why? Because for many the thought of actually saving up to buy something is simply anathema. We are in the era of instant gratification. A lot of young people want things, and they want them now! So what do they do? They pull out those credit cards that aren’t already maxed out and continue to accumulate more debt.

And what about those houses that are now worth less than the mortgages? Why would a couple in their late 20s or early 30s opt to buy a $600,000 or $700,000 house with 5% down, an adjustable-rate mortgage, a balloon second mortgage and monthly payments of $5,000 or $6,000?

Why? Because they just HAD to have THAT house–even though common sense told them that home prices during the so-called “housing boom” were grossly over-inflated.

Call me old-fashioned, but I can guarantee you that there is no way I would have done that when I was starting out. That is what a lot of those Gen X-ers and Gen Y-ers did. And now many are suffering because of the choices they made.

The Census Bureau report comes just before the Nov. 23 deadline for a special congressional committee to propose $1.2 trillion in budget cuts over ten years.

But more importantly, it has created questions about the government safety net that has sustained older Americans on Social Security and Medicare amid cuts to education and other programs, including cash assistance for low-income families.

“It makes us wonder whether the extraordinary amount of resources we spend on retirees and their health care should be at least partially reallocated to those who are hurting worse than them,” said Harry Holzer, a labor economist and public policy professor at Georgetown University who called the magnitude of the wealth gap “striking.”

Wait a minute! The money that retirees are getting from Social Security and Medicare is money that they paid into the system all their working lives. Are they supposed to feel guilty about that? Older Americans paid into a system that was set up to supplement savings and private sector retirement plans such as profit sharing, employee stock ownership schemes, and savings incentive plans.

Social Security and Medicare are NOT entitlement programs. They are NOT welfare plans for retirees. In fact, the money retirees take out of Social Security and Medicare is in essence money they have loaned the federal government. That the federal government spent that money unwisely or delved into it to fund other programs is not the fault of those who made good faith payments into the system.

There is no doubt that the numbers contained in the Census Bureau report are striking. For example, the median net worth of households headed by someone 65 or older is $170,494. That is 42 percent more than in 1984 when the Census Bureau first began measuring wealth broken down by age.

The median net worth for the younger-age households was $3,662, down by 68 percent from a quarter-century ago, according to the analysis by the Pew Research Center. In all, 37 percent of younger-age households have a net worth of zero or less, nearly double the share in 1984. But among households headed by a person 65 or older, the percentage in that category has been largely unchanged at 8 percent.

Net worth includes the value of a person’s home, possessions and savings accumulated over the years, including stocks, bank accounts, real estate, cars, boats or other property, minus any debt such as mortgages, college loans, and credit card bills. Older Americans tend to hold more net worth because they are more likely to have paid off their mortgages and built up more savings from salary, stocks and other investments over time. The median is the midpoint, and thus refers to a typical household.

Households headed by someone under age 35 saw their median net worth reduced by 27 percent in 2014 as a result of unsecured liabilities, mostly a combination of credit card debt, mortgages and student loans. No other age group had anywhere near that level of unsecured liability acting as a drag on net worth. The next closest was the 35-44 age group, at 10 percent.

Among the older-age households, the share of households worth at least $250,000 rose to 20 percent from 8 percent in 1984.

It is highly irritating and unfair to blame retirees for the plight of the younger generation. Unless of course, those retirees didn’t do their job in rearing fiscally responsible offspring or, even worse, encouraged them to pile up credit card debt by promising them that a parental bail out was in the offing.

Retirees worked long and hard for whatever wealth they have managed to accumulate. And, as the Census Bureau report shows, most are NOT wealthy–not when only 20 percent have a median household net worth of $250,000 or more.

Most older Americans are working longer than their parents did. Both my parents were able to retire at 62. How many older Americans can do that today? Not many. In fact, most are working well into their late 60s and early 70s.

Indeed, the whole concept of “retirement” has transformed today. The notion of spending the alleged “Golden Years,” sitting on the front porch in a rocking chair watching squirrels and listening to birds, is simply hooey.

So when economists lament the fact that retirees have 47-times more household net worth than Generation X-ers or Generation Y-ers, I can’t help but to parapharase that old Smith Barney TV commercial that said: “They made money the old-fashioned way. They earned it.”

Amen to that.

(NEXT: When Does a Gap Become a Canyon? (Part 2)

August 19, 2021

Joseph Galloway, chronicler and champion of soldiers in Vietnam, dies at 79

Today, I am running an obituary of legendary Vietnam war correspondent Joe Galloway that appeared in the Stars & Stripes newspaper. Galloway passed away Wednesday. I hope you will take a look at it. Galloway was the quintessential war reporter–self-effacing, courageous, and honest in his powerful reporting. Ron Yates

In November 1965, journalist Joseph Galloway hitched a ride on an Army helicopter flying to the Ia Drang Valley, a rugged landscape of red dirt, brown elephant grass, and truck-size termite mounds in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam. Stepping off the chopper, he arrived at a battlefield that one Army pilot later called “hell on Earth, for a short period of time.”

Galloway, a 24-year-old reporter for United Press International, went on to witness and participate in the first major battle of the Vietnam War, in which an outmanned American battalion fought off three North Vietnamese Army regiments while taking heavy casualties. He carried an M16 rifle alongside his notebook and cameras, and in the heat of battle, he charged into the fray to pull an Army private out of the flames of a napalm blast.

“At that time and that place, he was a soldier,” Maj. Gen. Joseph Kellogg said more than three decades later when the Army awarded Galloway the Bronze Star Medal for his efforts to save the private. “He was a soldier in spirit, he was a soldier in actions and he was a soldier in deeds.”

Joe Galloway

Joe GallowayGalloway later recounted the battle in a best-selling book, “We Were Soldiers Once … and Young” (1992), written with retired Lt. Gen. Harold Moore, the U.S. battalion commander at Ia Drang. The book was adapted into the movie “We Were Soldiers” (2002), starring Mel Gibson as Moore and Barry Pepper as Galloway, and was acclaimed for its unflinching account of one of the war’s bloodiest battles.

“What I saw and wrote about broke my heart a thousand times, but it also gave me the best and most loyal friends of my life,” Galloway said in a 2001 interview with the Victoria Advocate, the Texas daily where he had once worked as a cub reporter. “The soldiers accepted me as one of them, and I can think of no higher honor.”

Galloway, whose reporting took him from the jungles of Vietnam to the halls of the Kremlin and the deserts of Iraq, was 79 when he died Aug. 18 at a hospital in Concord, North Carolina. The cause was complications from a heart attack, said his friend and former editor John Walcott.

In a journalism career that spanned nearly five decades, Galloway became known for writing elegant, richly detailed stories that immersed readers in conflicts around the world, including the 1971 war between India and Pakistan and the 1991 Persian Gulf War, which he covered while embedded with a tank unit for U.S. News & World Report.

A native Texan who grew up reading the collected reporting of Ernie Pyle, who told the story of World War II through the eyes of ordinary GIs, Galloway exalted the bravery of American soldiers even as he questioned the wisdom of the leaders who sent them into battle. Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, who led U.S. forces during the Gulf War, once called him “the finest combat correspondent of our generation — a soldiers’ reporter and a soldiers’ friend.”

Galloway spent 22 years with UPI and retired in 2010 after working as a military affairs correspondent and columnist for the newspaper chains Knight Ridder and McClatchy, where he wrote critically of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars. He was played by Tommy Lee Jones in director Rob Reiner’s movie “Shock and Awe” (2017), about Knight Ridder’s skeptical coverage of the George W. Bush administration’s case for invading Iraq.

But he remained best known for his books and articles about Vietnam, most notably “We Were Soldiers Once … and Young,” which sold more than 1 million copies. He and Moore spent 10 years researching the volume, interviewing more than 250 people, including Vietnamese military commanders and U.S. veterans and their families.

“It is thoroughly researched, written with equal rations of pride and anguish, and it goes as far as any book yet written toward answering the hoary question of what combat is really like,” author and Vietnam War correspondent Nicholas Proffitt wrote in a review for the New York Times. He went on to call it “a car crash of a book; you are horrified by what you’re seeing, but you can’t take your eyes off it.”

The Battle of Ia Drang began Nov. 14, 1965, after Moore and some 450 soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry were helicoptered to a clearing known as Landing Zone X-Ray. They were there on a search-and-destroy mission — “It’s probably gonna be a long, hot walk in the sun,” the brigade commander had told Galloway — and soon came under withering fire.

Galloway and Moore speak at an American Veterans Center conference in Washington in 2008.

Galloway and Moore speak at an American Veterans Center conference in Washington in 2008.

For the next three days, they struggled to fight off North Vietnamese regulars, sometimes in bloody hand-to-hand combat. Helicopter gunships, fighter-bombers, and artillery fire helped turn the tide, although a replacement battalion was ambushed and nearly wiped out while marching to another clearing, Landing Zone Albany, in what Galloway and Moore described as “the most savage one-day battle of the Vietnam War.”

By the end of the fighting, more than 230 Americans and some 3,000 North Vietnamese were dead at Ia Drang. Both sides claimed victory: North Vietnamese leaders came away certain that they could outlast the Americans, while U.S. commander William Westmoreland was convinced that his troops “could bleed the enemy to death over the long haul,” as Galloway and Moore put it.

Galloway, who had arrived on the first night of the battle, said he planned for years to write a book with Moore but had put it off until 1980, when he was flipping channels and came across a Vietnam War sequence in the movie “More American Graffiti,” which brought back memories of Huey helicopters and deafening machine-gun fire.

“I found myself sitting in my chair, shaking like a leaf, with tears rolling down my cheeks at the sight and the memories,” he told Vietnam Magazine in 2017. “I thought, you can run from it, and it will catch you and eat you — or you can face it. I picked up the phone the next morning and called General Moore at his home in Colorado. ‘Are you ready to start work on this book?’ He said, ‘I sure am.’ “

Few memories of Ia Drang were more painful for Galloway than the death of Pfc. Jimmy Nakayama, one of two soldiers who were accidentally hit with napalm during a misplaced airstrike on the battle’s second day. Joined by an Army medic who was immediately shot and killed, Galloway raced toward enemy fire to pull Nakayama from the flames. The private was evacuated but died in a hospital two days later.

After the Pentagon reopened nominations for Vietnam battlefield honors, Galloway was awarded the Bronze Star Medal in 1998, becoming the fourth American journalist to receive the honor for bravery in the conflict.

“I accept it,” he said at the time, “in memory of the 70-plus reporters and photographers who were killed covering the Vietnam War, trying to tell the truth and keep the country free.”

Joseph Lee Galloway Jr. was born in Bryan, Texas, on Nov. 13, 1941, three weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His father served in the Army during World War II — Galloway did not meet him until after the war had ended — and later got a job with Humble Oil, leading the family to move to Refugio, Texas.

Galloway attended community college for six weeks before dropping out in 1959 to enlist in the Army, which he viewed as a ticket out of South Texas. His mother persuaded him to go into journalism instead, reminding him that as a boy he had written a weekly newspaper for their neighborhood, banging away at a 1912 Remington typewriter.

He joined UPI in 1961 as a reporter in Kansas City, Mo., and within two years he was bureau chief in Topeka, Kan., where he pestered the news agency’s senior editors to send him to Vietnam, sensing from dispatches by Neil Sheehan of UPI and David Halberstam of the Times that conflict there was escalating.

Galloway got his wish in April 1965, landing in South Vietnam a month after the first American combat troops arrived in the country. He remained there for 16 months and was later UPI bureau chief in Jakarta, the Indonesian capital, and in New Delhi, Singapore, Moscow and Los Angeles.

He later won a National Magazine Award at U.S. News & World Report, for a cover story about the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Ia Drang, and worked as a special consultant to Secretary of State Colin Powell before joining Knight Ridder in 2002.

Galloway’s wife of 29 years, the former Theresa Null, died in 1996. His second marriage — to Karen Metsker, whose father was killed at Ia Drang — ended in divorce, and in 2012 he married Grace Liem Lim Suan Tzu, who worked as a nurse’s helper during the Vietnam War.

In addition to his wife, of Concord, survivors include two sons from his first marriage, Lee Galloway of San Antonio and Joshua Galloway of Houston; a stepdaughter, Li Mei of Concord; and three grandchildren.

Galloway (center) with the 1st Cav in Vietnam, 1965

Galloway (center) with the 1st Cav in Vietnam, 1965Galloway partnered with Moore on another book, “We Are Soldiers Still” (2008), and teamed with Marvin J. Wolf to write “They Were Soldiers” (2020), about the postwar lives of Vietnam veterans. He also appeared in documentaries such as “The Vietnam War” (2017), directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

“You do this out of a sense of obligation to those who died and those who lived — those especially,” he told Newsday in 1993. “Their battle had been forgotten. You just can’t turn your back on something like that, not if you’ve seen it with your own eyes.”

When Galloway arrived in Vietnam in early 1965, “I knew nothing about war except what I had learned from watching John Wayne movies,” he said in a 2015 interview. He said he thought the war would be over quickly after Marines landed in Vietnam.

“My first week on the ground with the Marines taught me that that was probably not the case. That was out of sheer ignorance of the situation, of the enemy, of the culture, of the country. I was as ignorant as most Americans were, but I had to learn very quickly and combat is a very stiff taskmaster. You learn quickly or you get killed.”

Eventually, he came to realize that the war would take massive resources, especially with Vietnam’s large borders that could easily be infiltrated by both sea and land.

After the 1st Cavalry Division, along with its 435 helicopters, arrived in Vietnam in September 1965, Galloway began covering the First Team.

One of his early experiences with the 1st Cavalry was a march with the 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry Regiment. The soldiers had marched all day through thick jungle, into a high altitude level, crossing a stream.“Right before dark, we forded a swift mountain stream, quite cold. It was about neck-deep,” Galloway said.

They camped for the night in a clearing on the other side of the stream. No fires, cigarettes, or other lights were allowed.

“It was probably the coldest night I’d ever spent wrapped in a poncho, just wet. The next morning I thought would never come.”

But eventually, it did, and as the light was coming over the horizon, Galloway took out a piece of C-4 explosive to boil some water for coffee.

“I had just got my canteen cup boiling and was about to put the coffee powder in, and I looked up and there were two guys standing on the lip of my foxhole: a lieutenant colonel named Hal Moore and his battalion sergeant major, Basil Plumley,” Galloway said in 2015. “Moore looked at me and he looked at my hot water, and he said, ‘Son, in my outfit, everybody shaves in the morning, including reporters.’ … I shook my head and dug out my razor and my soap, and re-purposed my canteen cup of hot water.”

Moore and Galloway eventually became close friends.

August 17, 2021

Writing for Nonreaders in the Post-Print Era

Today, I am reposting a commentary I wrote while I was the Dean of the College of Media at the University of Illinois. At the time I taught classes in journalism and shared this with my students. It still resonates with me even though I wrote it about ten years ago. Please enjoy and feel free to comment.

Recently a professor (I won’t say who) created an outline for a new course called: “Writing for Nonreaders in the Post-Print Era.”

The course carried the following description:

“As print takes its place alongside smoke signals, cuneiform, and hollering, there has emerged a new literary age, one in which writers no longer need to feel encumbered by the paper cuts, reading, and excessive use of words traditionally associated with the writing trade. Writing for Nonreaders in the Postprint Era focuses on the creation of short-form prose that is not intended to be reproduced on pulp fibers.

“Instant messaging. Tweeting. Blogging. Facebook & Google+ updates. Pinning. These 21st-century literary genres are defining a new “Lost Generation” of minimalists who would much rather watch Modern Family on their iPhones than toil over long-winded articles and short stories.

Students will acquire the tools needed to make their tweets glimmer with a complete lack of forethought, their Facebook updates ring with self-importance, and their blog entries shimmer with literary pithiness. All without the restraints of writing in complete sentences. w00t! w00t!

Throughout the course, a further paring down of the Hemingway/Stein school of minimalism will be emphasized, limiting the superfluous use of nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives, conjunctions, gerunds, and other literary pitfalls.”

Prerequisites

Students must have completed at least two of the following.:

ENG: 232WR—Advanced Tweeting: The Elements of Droll

LIT: 223—Early-21st-Century Literature: 140 Characters or Less

ENG: 102—Staring Blankly at Handheld Devices While Others Are Talking

ENG: 301—Advanced Blog and Book Skimming

ENG: 231WR—Facebook Wall Alliteration and Assonance

LIT: 202—The Literary Merits of LoLcats

LIT: 209—Internet-Age Surrealistic Narcissism and Self-Absorption

There is obviously some truth at work here. When one talks to editors in the world of book publishing it is apparent that we are definitely entering the post-print era. Few students I talk with tell me they actually read a book for pleasure. It is always for a class.

When I ask students about John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Lillian Hellman, Dorothy Parker—even Earnest Hemmingway, only a few can tell me much about these authors and what they wrote. If they have read these writers at all it is because some American Literature teacher in high school assigned them to read one of their books or essays.

Take some time over a weekend to read a good book—one that tells a story, not some self-absorbed treatise on how to find your spiritual center or why you are so important, I tell students. You might actually enjoy it—and without a doubt, you will learn something.

When I discuss writing with journalism students, who should have a keen interest in writing well, I tell them that the best way to learn to write well is to read good writing. They should then learn to imitate that writing—not copy or plagiarize it—but imitate it. Eventually, they will develop their own style of writing, but most important, they will become better writers simply because they have developed a life-long romance with and respect for the English language.

So while Facebook, Google+ and My Yahoo may be places to chat and hook up; while the blogosphere is a place where tedious pontificators can congregate with little if any accountability for truth; and while twittering is the latest e-rage, they are all poor substitutes for substantive literature, fine journalism or intelligent conversation.

The university is the place where an appreciation for good literature, fine journalism, and intelligent conversation should be cultivated and enjoyed. It is, after all, one of the few times when students will actually have the time to take pleasure in these things.

Once they enter the world of gainful employment, their focus will shift to one of survival, meeting deadlines and accumulating “stuff.”

Reading well will be considerably more challenging. And one can only hope that they will not find themselves “Writing for Nonreaders in the Post-Print Era.”

August 16, 2021

Update: Is Afghanistan 2021 a Reprise of Vietnam 1975?

America’s 20-year war in Afghanistan with an enemy and a people still stuck in the Middle Ages has ended.

Finally.

And just as it was 47 years ago in a place called Vietnam, it did not end in victory.

That became clear on Sunday when Taliban forces entered Kabul essentially unimpeded by a collapsing Afghan army. On the way, they released thousands of Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters from a prison on the outskirts of the capital.

Early on in the conflict, America’s military crushed Al Qaeda and neutralized the Taliban. But for the past ten years or so, the war was little more than a holding action against an enemy that worked assiduously to consolidate its power via a loose alliance of warlords and their private armies.

As they did, the Taliban kept gaining more and more territory until by early this year, it controlled almost four-fifths of the country’s landmass.

Fighting the Taliban, like fighting the Viet Cong in Vietnam, was like trying to kill a cobra by hacking at its tail. American and coalition forces could never cut off the head of the snake because there really wasn’t one–or if there was, they never found it.

In April 1975, I watched the communist North Vietnamese Army move inexorably south from Hue, Da Nang, Nha Trang, and Cam Ranh Bay until they were on the outskirts of Bien Hoa, just 25 miles from Saigon.

Under terms of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, North Vietnamese troops were not supposed to be south of the 17th parallel.

But they were, and they were moving fast.

The U.S. Congress ignored pleas for help by the South Vietnamese government and America’s ambassador in Saigon. For those who may have forgotten, in April 1975, then-U.S. Sen. Joe Biden argued against $1 billion in emergency aid for South Vietnam, insisting that the South Vietnamese military might use the money.

Today, Biden is president, and his actions vis-à-vis Afghanistan are receiving fitting criticism—especially for what appears to be a mounting humanitarian crisis.

Some 400,000 Afghani civilians have been forced from their homes since the start of the year, 250,000 of them since May. Families are camping out in a Kabul park with little or no shelter, having escaped violence elsewhere in the country. In all, some 2.9 million Afghan civilians have been displaced since the war began in 2001.

Taliban forces now control all of Afghanistan in the wake of America’s decision to withdraw. Thousands of Afghan soldiers in what Biden bragged a couple of months ago was a “well-equipped and trained” Afghan army of 300,000, were seen frantically discarding their uniforms and weapons and running for safety as Taliban forces entered Kabul.

I watched soldiers in the South Vietnamese army do the same thing 47 years ago as the NVA entered Saigon.

Was it a disgusting display of rank cowardice? Possibly. But it was also thousands of soldiers recognizing the fact that the war for the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese people was lost. The communist north had won. Why die for a lost cause?

The situation in Afghanistan is hauntingly similar.

“The situation has all the hallmarks of a humanitarian catastrophe,” an official with the U.N. World Food Program’s told reporters.

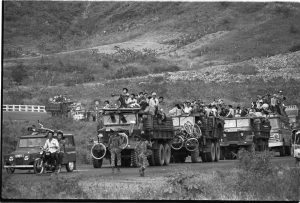

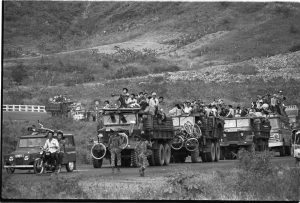

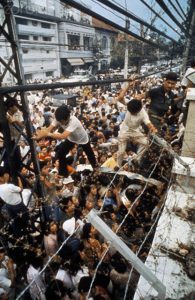

Vietnamese fleeing south in front of communist forces April 1975 (Ron Yates)

Vietnamese fleeing south in front of communist forces April 1975 (Ron Yates)During the fall of South Vietnam, I witnessed tens of thousands of terrified South Vietnamese driven from their homes by violence and war move south along Highway One—some in over-loaded trucks crammed with people and whatever belongings they could carry.

Fifty or 60 miles behind them, the North Vietnamese Army trailed them with tanks and trucks.

Today, we are seeing a replay of that event in Afghanistan.

Taliban on the Move

Taliban on the Move In response, the State Department reduced its staff in the U. S. Embassy in Kabul and has instructed all U.S. personnel to destroy items like documents and electronic devices to “reduce the amount of sensitive material on the property,” according to an internal notice obtained by reporters.

“Please also include items with embassy or agency logos, Americans flags, or items which could be misused in propaganda efforts,” the notice said.

Forty-seven years ago, the same thing happened in the American Embassy in Saigon. Shredding machines were working overtime, bonfires were burning sensitive material inside the vast embassy compound, and embassy staff was being flown out of Tan Son Nhut airport secretly a few at a time.

South Vietnamese who had worked for and with the U.S. military in Vietnam watched in horror as their country fell apart day after day between March and April 1975. Many began fleeing the country a few weeks before the North Vietnamese entered the city—terrified that their cooperation with the Americans would mean certain death.

For many who were left behind during the chaotic evacuation of Saigon, those fears were realized—if not immediately after the NVA entered the city, then months and even years later when they were thrown into communist concentration camps euphemistically referred to as “reeducation camps.”

As events unfold in Afghanistan, I wonder what will happen to the thousands of Afghanis who worked for Americans and their coalition partners. Hundreds of not thousands of Afghanis loyal to the United States and other coalition nations will likely be slaughtered by a ruthless and vengeful Taliban.

The Biden administration says it is prepared to begin evacuation flights for Afghan interpreters and translators who aided the U.S. military effort in the 20-year war — but their destinations are still unknown.

Now, with the Taliban inside of Kabul, there are troubling questions about how to ensure their safety until they can get on planes–if they ever do.

Poor evacuation planning by the Biden administration could potentially affect tens of thousands of Afghans. Several thousand Afghans who worked for the United States — plus their family members — are already in the application pipeline for special immigrant visas. But now that the Taliban are in Kabul and possibly surrounding the U.S. Embassy, you have to wonder how the evacuation apparatus will function.

Kandahar falls to Taliban

Kandahar falls to Taliban“What this is not — this is not abandonment. This is not an evacuation. This is not the wholesale withdrawal,” State Department spokesman Ned Price insisted Thursday.

It isn’t? It certainly looks that way. And what about those vulnerable 18,000 or so Afghanis who risked their lives working for American and coalition forces as interpreters, drivers, and fixers, etc.?

There are still too many unanswered questions—just as there were in Saigon in 1975. Almost every day leading up to the final evacuation, I was confronted by anguished and panicked Vietnamese worried about how they could get on an evacuation flight before the communist takeover.

How many people are eligible for evacuation in Afghanistan? How will those outside the capital reach safety to be evacuated? To what countries will they be evacuated?

And what of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani?

Not to worry about him. He fled the country Saturday rather than face what might have been certain death at the hands of the Taliban and their Al Qaeda brothers.

So, is Afghanistan 2021 a repeat of South Vietnam 1975?

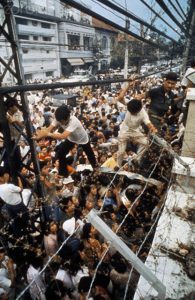

Panicked Vietnamese try to storm U.S. Embassy, April 29, 1975

Panicked Vietnamese try to storm U.S. Embassy, April 29, 1975Clearly, these are entirely different countries with entirely different issues. The NVA was a highly mechanized, disciplined, and unified professional army. The Taliban is a loose conglomeration of warlords and disparate Afghani tribes, whose members have long memories and who have sworn vengeance against their enemies.

But there are also similarities, and probably the most troubling for me, is what happens to those Afghanis who put their lives and futures on the line by working for Americans?

I know what happened to tens of thousands of Vietnamese who were left behind when U.S. Marine helicopters ferried 1,373 Americans and 5,680 Vietnamese to safety from a chaotic and frenzied Saigon between April 29 and April 30, 1975.

They were abandoned, executed, imprisoned, tortured, and forgotten.

Will things be different in Afghanistan?

August 14, 2021

Is Afghanistan 2021 a Reprise of Vietnam 1975?

In April 1975, I watched the communist North Vietnamese Army move inexorably south from Hue, Da Nang, Nha Trang, and Cam Ranh Bay until they were on the outskirts of Bien Hoa, just 25 miles from Saigon.

Under terms of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, North Vietnamese troops were not supposed to be south of the 17th parallel.

But they were, and they were moving fast.

The U.S. Congress ignored pleas for help by the South Vietnamese government. For those who may have forgotten, in April 1975, then-U.S. Sen. Joe Biden voted against $1 billion in emergency aid for South Vietnam, insisting that the South Vietnamese military might use the money.

Today, Biden is president, and his actions vis-à-vis Afghanistan are receiving a lot of criticism—especially for what appears to be a mounting humanitarian crisis.

Some 400,000 Afghani civilians have been forced from their homes since the start of the year, 250,000 of them since May. Families are camping out in a Kabul park with little or no shelter, having escaped violence elsewhere in the country. Some 2.9 million Afghan civilians have been displaced since the war began in 2001.

Vietnamese fleeing south in front of communist forces April 1975

Vietnamese fleeing south in front of communist forces April 1975“The situation has all the hallmarks of a humanitarian catastrophe,” an official with the U.N. World Food Program’s told reporters.

During the fall of South Vietnam, I watched tens of thousands of terrified South Vietnamese driven from their homes by violence and war move south along Highway One—some in over-loaded trucks crammed with people and whatever belongings they could carry.

Fifty or 60 miles behind them, the North Vietnamese Army was trailing them with tanks and trucks.

Today, I am watching what seems to be a replay of that event in Afghanistan.

Taliban forces are moving very fast toward the capital of Kabul. Like the NVA, which controlled about four-fifths of Vietnam by early April 1975, Taliban forces are edging closer to controlling all of Afghanistan since the harried pull-out of American troops.

Taliban on the Move toward Kabul

Taliban on the Move toward KabulIn response, the State Department has reduced its staff in the U. S. Embassy in Kabul and has instructed all U.S. personnel to destroy items like documents and electronic devices to “reduce the amount of sensitive material on the property,” according to an internal notice obtained by reporters.

“Please also include items with embassy or agency logos, Americans flags, or items which could be misused in propaganda efforts,” the notice said.

Forty-seven years ago, the same thing happened in the American Embassy in Saigon. Shredding machines were working overtime, bonfires were burning sensitive material inside the vast embassy compound, and embassy staff was being flown out of Tan Son Nhut airport secretly a few at a time.

South Vietnamese who had worked for and with the U.S. military in Vietnam watched in horror as their country fell apart day after day between March and April 1975. Many began fleeing the country a few weeks before the North Vietnamese entered the city—terrified that their cooperation with the Americans would mean certain death.

For many who were left behind during the chaotic evacuation of Saigon, those fears were realized—if not immediately after the NVA entered the city, then months and even years later when they were thrown into communist concentration camps euphemistically referred to as “reeducation camps.”

As events unfold in Afghanistan, I wonder what will happen to the thousands of Afghanis who worked for the Americans.

The Biden administration says it is prepared to begin evacuation flights for Afghan interpreters and translators who aided the U.S. military effort in the 20-year war — but their destinations are still unknown. There are lingering questions about how to ensure their safety until they can get on planes.

The evacuation planning could potentially affect tens of thousands of Afghans. Several thousand Afghans who worked for the United States — plus their family members — are already in the application pipeline for special immigrant visas.

Meanwhile, on Thursday, the Taliban took Herat, Afghanistan’s third-largest city. By Friday, the Taliban had taken control of Kandahar, the country’s second-largest city, 300 miles south of Kabul, and considered the birthplace of the Taliban. The Taliban has also seized Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand province.

Kandahar falls to Taliban

Kandahar falls to Taliban“What this is not — this is not abandonment. This is not an evacuation. This is not the wholesale withdrawal,” State Department spokesman Ned Price said Thursday. “What this is, is a reduction in the size of our civilian footprint. This is a drawdown of civilian Americans who will, in many cases, be able to perform their important functions elsewhere, whether that’s in the United States or elsewhere in the region.”

Okay, but what about those vulnerable 18,000 or so Afghanis who risked their lives working for American and coalition forces as interpreters, drivers, and fixers, etc.?

There are still too many unanswered questions—just as there were in Saigon in 1975. Almost every day leading up to the final evacuation, I was confronted by Vietnamese apprehensive about how they could get on an evacuation flight before the communist takeover.

How many people are eligible for evacuation in Afghanistan? How will those outside the capital reach safety to be evacuated, and to what countries will they be evacuated?

And what of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani? The Taliban have demanded that Ghani resign in exchange for a reduction in violence and to lay the groundwork for a transitional government. But Ghani has said he is the country’s democratically elected leader and will remain so until negotiations between the Taliban and Afghan government conclude.

Today that seems like an increasingly distant reality.

So, is Afghanistan 2021 a repeat of South Vietnam 1975?

Panicked Vietnamese try to storm U.S. Embassy, April 29, 1975

Panicked Vietnamese try to storm U.S. Embassy, April 29, 1975Clearly, these are entirely different countries with entirely different issues. The NVA was a highly mechanized, disciplined, and unified professional army. The Taliban is a loose conglomeration of warlords and disparate Afghani tribes.

But there are also similarities, and probably the most troubling for me, is what happens to those Afghanis who put their lives and futures on the line by working for Americans?

I know what happened to tens of thousands of Vietnamese who were left behind when U.S. Marine helicopters ferried 1,373 Americans, 5,680 Vietnamese to safety from a chaotic and frenzied Saigon between April 29 and April 30, 1975.

They were abandoned, executed, imprisoned, tortured, and forgotten.

Will things be different in Afghanistan?

August 13, 2021

A New School Prayer

This has been around awhile, but I just read it again and I thought I would share it with my followers. Whether you agree or not with the prayer’s premise it seems sad that this is where we are as a country.

One common misconception is that the Supreme Court has ruled that praying in school is not allowed. In fact, what is impermissible is a school’s sponsorship of a religious message. Praying in school is not against the law. In fact, the U.S. Constitution guarantees students the right to pray in public schools; it is a protected form of free speech.

A student can pray on the school bus, in the corridors, in the cafeteria, in their student-run Bible club, at the flagpole, sports stadium, and elsewhere on school grounds. They can even pray silently before and after class in the classroom. However, they are not allowed to pray only one religion’s prayers at the exclusion of other religions as an organized part of the school schedule.

Prayers in public schools cannot be solely from a single religious faith group because, as the Supreme Court has ruled “that sends the ancillary message to members of the audience who are non-adherents that they are outsiders, not full members of the political community, and an accompanying message to adherents that they are insiders, favored members of the political community.”

Of course, some argue that the negative attitude of local school boards toward prayer in public schools in the wake of that Supreme Court ruling has had a chilling effect on children who want to pray. That may be what prompted somebody (nobody knows exactly who) to pen the following “New School Prayer” a few years ago.

A New School Prayer

Now I sit me down in school

Where praying is against the rule

For this great nation under God

Finds mention of Him very odd.

If Scripture now the class recites,

It violates the Bill of Rights.

And anytime my head I bow

It becomes a Federal matter now.

Our hair can be purple, orange or green,

That’s no offense; it’s a freedom scene.

The law is specific, the law is precise.

Prayers spoken aloud are a serious vice.

For praying in a public hall

Might offend someone with no faith at all.

In silence alone, we must meditate,

God’s name is prohibited by the state.

We’re allowed to cuss and dress like freaks,

And pierce our noses, tongues, and cheeks.

They’ve outlawed guns, but FIRST the Bible.

To quote the Good Book makes me liable.

We can elect a pregnant Senior Queen,

And the ‘unwed daddy,’ our Senior King.

It’s “inappropriate” to teach right from wrong,

We’re taught that such “judgments” do not belong.

We can get our condoms and birth controls,

Study witchcraft, vampires and totem poles.

But the Ten Commandments are not allowed,

No word of God must reach this crowd.

It’s scary here I must confess,

When chaos reigns the school’s a mess.

So, Lord, this silent plea I make:

Should I be shot; My soul please take!

Amen

August 12, 2021

Test Your Knowledge of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War ended 47 years ago on April 30, 1975. For those of us who lived through it and the turmoil it created in the United States, it still seems like yesterday. For those of you who view the war as ancient history, here’s a chance to test your knowledge.

Few wars in American history are as misunderstood and filled with misinformation and disinformation as the undeclared war in Vietnam. For example one of the enduring myths about Vietnam is that the war was fought predominantly by draftees. In fact, according to statistics kept by the US Army, and corroborated by other sources, only 25% of the troops who served in combat roles in Vietnam were drafted into military service.

Another myth is that a higher percentage of poor black soldiers fought the Vietnam War than middle class white soldiers. In fact, Pentagon figures show that of the troops who deployed to Vietnam during the years of American involvement, including the crews of the US Navy ships which served offshore in the conflict, about 50 percent came from middle-class backgrounds, were better educated than in any of America’s preceding wars (79% had a high school diploma), and were overwhelmingly white (88%). Of all the combat deaths suffered by American forces over the course of the war, 86% were white.

Take this test to see how much you know about the war that divided our country more than any other war since the Civil War in 1861-65.

Click on the link below.

http://history.howstuffworks.com/historical-events/vietnam-war-quiz.htm.

August 11, 2021

A Peek at My High School Yearbook: How on Earth Did I Pass my FBI Background Check?

Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh is once again under attack, this time by a group of seven socialist-Democrat Senators who claimed this week that recently released material from the FBI shows the agency failed to “fully investigate” Kavanaugh during his confirmation hearings after being nominated by President Donald Trump. The group is pushing for Kavanaugh’s impeachment.

Stay tuned. The hateful obsession with Justice Kavanaugh seems to have no statute of limitation. It just keeps going on and on.

Do you remember the intense scrutiny Justice Kavanaugh’s high school yearbook received from the Senate Judicial Committee in 2018? What horrendous secrets and activities were hidden on those pages? What horrible things did Brett Kavanaugh do as a teenager?

The answers must reside somewhere in the pages of his yearbook.

Then, I began to wonder about my old high school yearbook. What reproachful and censorious information did it contain about me?

So, I pulled my high school yearbook off the shelf the other day and took a careful look at it. Afterward, I wondered how I passed the FBI background check for my U.S. Army Security Agency Top Secret & Crypto security clearance back in the 1960s.

There were some pretty spicy comments in there, especially from former girlfriends. One girl even thanked me because in the biology class we took together “you knew all the answers.”

My Yearbook

My YearbookI can only assume she meant answers to biology tests. Of course, in today’s hyper-sensitive world that cryptic statement could mean a lot of things. Ahem.

Other girlfriends said they were happy to have known me and thanked me for the “good times” we had together. What did they mean by THAT? Did I do something inappropriate? Hmmmm. Well, let me see. There were those times when we used to “make out” in the backseat on double dates. . . .

Sometimes we even (gasp) drank 3.2% beer that I used to buy illegally (uh oh!) before I was 18—the drinking age in Kansas. I don’t ever recall barfing or ralfing after a few cans of the insipid stuff like Judge Kavanaugh has been accused of doing, but I’m sure all of us (our girlfriends included) got a buzz on. Then we had to consume mass quantities of Sen-Sen mints before going home to hide the telltale beer pong on our breaths.

I have wracked my brain trying to recall any gang rape parties that I might have attended, and for the life of me, I can’t recollect any. I am pretty sure I never attended any in which I was the featured attraction. Of course, something as hazy and ambiguous as a gang rape is undeniably challenging to recall. I do remember going to a lot of “sock hops” in the high school gym during which guys and girls removed their shoes (gulp) and danced in our socks (how salacious and naughty).

Then there were those evenings at Winstead’s in Kansas City’s Country Club Plaza where several of us unruly and rowdy couples would stuff ourselves into a booth and be crushed against one another while we drank malted-milks and wolfed down fries and steakburgers. I do recall once dropping ketchup on my date’s new crinoline pink and white poodle skirt. Boy, was she pissed! But she still gave me a goodnight kiss when I walked her to her door. So all was well. At least, I think it was. . . .

Okay, back to my yearbook. It was called “The Indian.” I know, I know. Not politically correct. In fact, those of us who attended Shawnee-Mission North (my high school in the Overland Park, Kansas suburbs of Kansas City) were called “The Indians” as opposed to some politically safe name like the Wildcats or the Cyclones.

Were we really “Indians?” I’m pretty sure there wasn’t one real Native American in the entire student body. It was, without a doubt, the most shocking form of cultural appropriation, and for that, I apologize. But wait! Shawnee-Mission North is still “The Indians,” and the logo is still a Native American wearing a war bonnet. Oh well. No need to apologize, after all. That association won’t get me denounced and pilloried by the Senate Judiciary Committee.

But back to my misspent youth when I was going to all of those risqué sock hops, making out in the back seat of jalopies, having “good times” with girlfriends, and providing them with “all the answers.”

Given all of the terrible things I did when I was 16, 17, and even 18, I wonder how I was able to live a mostly efficacious and praiseworthy life—first as an intelligence operative in the U.S. Army, then as a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, and then as a Professor and Dean of journalism at the University of Illinois. Will wonders never cease?

I can only imagine what my life would have been like had I been subjected to the same rapacious grilling that Judge Kavanaugh endured at the hands of some of the members of the Senate Judicial Committee.

If all of my teenage years had been disclosed publicly, I’m pretty sure I would have been disqualified by the Court of Public Opinion, let alone from the Supreme Court of the United States.

But wait. I don’t even have a law degree. Oh, well. Never mind.

August 6, 2021

The Diminished Meaning of the Word “Hero”

Our society seems obsessed with labels. Take the word “Hero,” for example. It is applied in the most absurd and inappropriate ways to people who don’t deserve that distinction.

When Whitney Houston died in 2012, for example, I couldn’t believe people were calling her a “hero.”

Why? Because she was a wonderfully talented singer who eventually threw her life and career away with a deadly addiction to different drugs such crystal meth, marijuana, cocaine, and pills such as Xanax, Flexeril, and Benadryl?

How exactly does that make her a “hero?” It doesn’t. It doesn’t even make her a good role model.

And what about others who have been accorded the “hero” appellation?

Remember US Airways Capt. Chesley Sullenberger, who in 2009 landed his plane full of passengers on New York’s Hudson River after his engines conked out? Sullenberger was quickly labeled “hero”–a term he says is not appropriate.

U.S. Airways pilot Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger

U.S. Airways pilot Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger “That didn’t quite fit my situation, which was thrust upon me suddenly,” he said. “Certainly, my crew and I were up to the task. But I’m not sure it quite crosses the threshold of heroism. I think the idea of a hero is important. But sometimes in our culture, we overuse the word, and by overusing it, we diminish it.”

The Pittsburgh-based Carnegie Hero Fund Commission defines a hero as “someone who voluntarily leaves a point of safety to assume life risk to save or attempt to save the life of another.”

“When the engines stopped on US Airways Flight 1549 in January 2009,” Commission president, Mark Laskow wrote, “Capt. Sullenberger was not in a place of safety. On the contrary, he was in the same peril as the passengers whose lives he saved with his piloting skill. He did not have the opportunity to make a moral choice to take on the risk — it ‘was thrust upon him. I do not doubt that if he did have such a choice, he would not have hesitated to place himself in danger to save his passengers. That just wasn’t the actual situation in which he found himself.”

Once upon a time, I served in the U.S. Army. I did my job and did it pretty well as my various awards, and eventual promotion to Sergeant attests. But I was no “hero.” I volunteered, I did my job, and I left with an honorable discharge. When a soldier, marine, airman or sailor puts on his or her uniform, they are just doing their jobs.

Today, we apply the word “hero” to all servicemen and women who serve in the armed forces. How often do we hear people refer to “our heroes in Afghanistan?” They are not heroes. They are servicemen and women, and they are doing their duty serving their nation. When they are injured, wounded, or even killed they are casualties, but not necessarily heroes.

A hero is a person who goes above and beyond the call of duty and puts him or herself in harm’s way to perform an act of selfless gallantry. You might argue that servicemen and women put themselves in harm’s way on a daily basis, but that is their job–and they volunteered for that job. So how does that make “ALL” servicemen and women “heroes?”

It doesn’t.

I sometimes wear a baseball cap when I go shopping. On the front, it identifies me as a U.S. Army Veteran–a fact that I am very proud of. Sometimes people see that and thank me for my service. When that happens, I often feel a bit awkward. Yes, I did serve four years on active duty and another four in the reserves. But I don’t feel anybody owes me a “thank you.” I volunteered for the U. S. Army, and I did the job I was assigned to do. I am certainly no “hero” because of it.

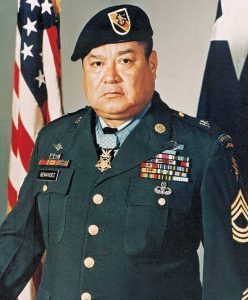

Do you want to know what a hero is? Here is a hero. His name was Roy P. Benavidez. Not long ago someone sent me an e-mail that contained the fantastic story of his life.

In 1965 Benavidez was sent to South Vietnam as a Green Beret advisor to an ARVN infantry regiment. He stepped on a landmine during a patrol and was evacuated to the United States, where doctors at Brooke Army Medical Center (BAMC) concluded he would never walk again and began preparing his medical discharge papers.

Master Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez

Master Sergeant Roy P. BenavidezBut Benavidez, who was known by the radio call sign as “Tango Mike Mike” (“That Mean Mexican”) was not ready to accept that diagnosis.

Against doctors’ orders, he began an unsanctioned nightly training ritual in an attempt to redevelop his ability to walk. Climbing out of bed at night, Benavidez would crawl using his elbows and chin to a wall near his bedside and (with the encouragement of his fellow patients, many of whom were permanently paralyzed or missing limbs), he would prop himself against the wall and attempt to lift himself up unaided.

After several months of excruciating practice that by his own admission often left him in tears, he was able to push himself up the wall with his ankles and legs. After more than a year of hospitalization, Benavidez walked out of the hospital in July 1966, with his wife at his side, determined to return to combat in Vietnam.

Benavidez returned to Fort Bragg to begin training for the elite Studies and Observations Group (SOG). Despite continuing pain from his wounds, he became a member of the 5th Special Forces Group and returned to South Vietnam in January 1968.

That’s when this man’s incredible story of heroism began. This is what his Medal of Honor Citation says:

“On the morning of 2 May 1968, a 12-man Special Forces Reconnaissance Team was inserted by helicopters in a dense jungle area west of Loc Ninh, Vietnam to gather intelligence information about confirmed large-scale enemy activity. This area was controlled and routinely patrolled by the North Vietnamese Army. After a short period of time on the ground, the team met heavy enemy resistance and requested emergency extraction.

“Three helicopters attempted extraction but were unable to land due to intense enemy small arms and anti-aircraft fire. Sergeant Benavidez was at the Forward Operating Base in Loc Ninh monitoring the operation by radio when these helicopters returned to off-load wounded crewmembers and to assess aircraft damage.

“Sergeant Benavidez voluntarily boarded a returning aircraft to assist in another extraction attempt. Realizing that all the team members were either dead or wounded and unable to move to the pickup zone, he directed the aircraft to a nearby clearing where he jumped from the hovering helicopter and ran approximately 75 meters under withering small arms fire to the crippled team.

“When he reached the leader’s body, Sergeant Benavidez was severely wounded by small arms fire in the abdomen and grenade fragments in his back. At nearly the same moment, the aircraft pilot was mortally wounded, and his helicopter crashed. Although in extremely critical condition due to his multiple wounds, Sergeant Benavidez secured the classified documents and made his way back to the wreckage, where he aided the wounded out of the overturned aircraft and gathered the stunned survivors into a defensive perimeter.

“Prior to reaching the team’s position he was wounded in his right leg, face, and head. Despite these painful injuries, he took charge, repositioning the team members and directing their fire to facilitate the landing of an extraction aircraft, and the loading of wounded and dead team members. He then threw smoke canisters to direct the aircraft to the team’s position. Despite his severe wounds and under intense enemy fire, he carried and dragged half of the wounded team members to the awaiting aircraft. He then provided protective fire by running alongside the aircraft as it moved to pick up the remaining team members. As the enemy’s fire intensified, he hurried to recover the body and classified documents on the dead team leader.

“Under increasing enemy automatic weapons and grenade fire, he moved around the perimeter distributing water and ammunition to his weary men, re-instilling in them a will to live and fight. Facing a buildup of enemy opposition with a beleaguered team, Sergeant Benavidez mustered his strength, began calling in tactical air strikes and directed the fire from supporting gunships to suppress the enemy’s fire and so permit another extraction attempt.

“He was wounded again in his thigh by small arms fire while administering first aid to a wounded team member just before another extraction helicopter was able to land. His indomitable spirit kept him going as he began to ferry his comrades to the craft. On his second trip with the wounded, he was clubbed from behind by an enemy soldier. In the ensuing hand-to-hand combat, he sustained additional wounds to his head and arms before killing his adversary. “

He then continued under devastating fire to carry the wounded to the helicopter. Upon reaching the aircraft, he spotted and killed two enemy soldiers who were rushing the craft from an angle that prevented the aircraft door gunner from firing upon them. With little strength remaining, he made one last trip to the perimeter to ensure that all classified material had been collected or destroyed, and to bring in the remaining wounded. Only then, in extremely serious condition from numerous wounds and loss of blood, did he allow himself to be pulled into the extraction aircraft.

“Sergeant Benavidez’ gallant choice to join voluntarily his comrades who were in critical straits, to expose himself constantly to withering enemy fire, and his refusal to be stopped despite numerous severe wounds, saved the lives of at least eight men. His fearless personal leadership, tenacious devotion to duty, and extremely valorous actions in the face of overwhelming odds were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflect the utmost credit on him and the United States Army.”

The citation stops short of telling what happened when the helicopter reached its base. Benavidez was put into a body bag, and as it was being zipped up, using what little strength he had left, he spits on the face of the medic to show he wasn’t dead.

Roy Benavidez died on November 29, 1998, at the age of 63 at Brooke Army Medical Center, after suffering respiratory failure and complications of diabetes. He was buried with full military honors at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery.

Now THAT is the definition of a HERO!

For those who want to see and hear more about Master Sergeant Roy P. Benavidez, you can do so by clicking on the following link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RZ7968BbMnU&feature=player_embedded

July 30, 2021

Q & A with Novel PASTimes Part 2

All historical fiction is, I think, a mixture of truth and story. Accuracy is beyond our reach since we have to imagine conversations and thoughts, but as novelists, we struggle to present an authentic, believable past whether or not our characters ever existed. When you talk about the Billy Battles novels being “faction,” do you have something more specific in mind?

All historical fiction is, I think, a mixture of truth and story. Accuracy is beyond our reach since we have to imagine conversations and thoughts, but as novelists, we struggle to present an authentic, believable past whether or not our characters ever existed. When you talk about the Billy Battles novels being “faction,” do you have something more specific in mind?That’s tricky. I call my work “Faction,” because it is both fact and fiction. Some of the events in the book–especially those dealing with real people, did happen. Was my character directly involved in them? No. However, members of my family were native Kansans, and some of the experiences I write about did happen. Of course, I have woven some of my own experiences into the storyline also. I think it is essential to weave as many of your own experiences as you can into the storyline. That gives the story a ring of truth or credibility if you will. Novelists ask readers to suspend belief when it comes to things their characters do, but if you are writing historical fiction especially, you must be faithful to the time and place in which the story takes place.

What caused you to make that shift away from journalism to a mix of fact and fiction?

It wasn’t a sudden shift. I always knew I wanted to write novels, but as a foreign correspondent I just never found the time. Then, in 1997 I left the Chicago Tribune to write a corporate biography of Japan’s Kikkoman Corp (the soy sauce maker which also happens to be Japan’s oldest continuously operating company dating back to 1630). When that was finished, I was offered a full, tenured professorship at the University of Illinois teaching journalism. A couple of years later I was made the Dean of the College of Media—so once again, no time to write my novels. Finally, in 2010, I left the university, moved to California, and began my novel-writing career.

Thanks for joining us here on Favorite PASTimes. Do you have any final words for readers or writers?

Yes! For Readers : Please DON’T STOP READING! Those of us who love telling stories need you. And when you read a book, don’t be shy. Write a review on Amazon, Goodreads, Barnes & Noble, etc., and let us know what you liked and didn’t like about a book. I value the reviews I get from Amazon Verified Purchase customers more than I do from professional or editorial reviewers. After all, customers spent money on the book and that gives them the right to tell the author what they think. For Writers: Please Keep Writing. The world needs good storytellers today more than ever. I know that many who write are frustrated by letters of rejection from agents and publishers. Don’t be discouraged. If you can’t get a book before the reading public going the traditional publishing route, consider self or indie publishing. Publish on Demand (POD) books are everywhere these days and so are e-books. Writers today don’t have to consider a rejection letter the last word in their aspiration to publish. You have options to reach readers that didn’t exist 10 or even five years ago. There are also scores of contests in which you can enter your books so you can measure your work with that of your peers. As I mentioned earlier, Chanticleer is an excellent example, as the Book Excellence Award which my books have won, as well as the New Apple Literary Award and the New York Big Book Award, where my books were also achieved recognition.

Having said that, I never wrote my books in pursuit of awards. I wrote them because I enjoyed writing them. And, I must be honest. Many self-published books are not well done. The writing may be of poor quality; the covers are often inferior, and the proofreading and editing are shoddy. Frankly, some books should never have made it off the printing press or into an e-file. However, there are enough gems coming from self-published authors to offset the marginal efforts.

My advice to beginners: Give yourself time to learn the craft of writing. How do you do that? Read, read, read. If you want to write well, read well. Learn from the best; imitate (and I don’t mean plagiarize). Listen to the words! You don’t have to spend thousands of dollars on writing seminars, conferences, etc. Gifted writing can’t be taught. It must be learned. And we learn from doing it; from experience. To be a good writer you need to be confident in your ability to use the tools of the craft: research, vocabulary, grammar, style, plot, pacing, and story. A confident writer is typically a good writer. We gain confidence by being successful in our work–no matter what work we do. We also learn from failure. Why was a book rejected 40 times? Why isn’t it selling on Amazon or Goodreads or Barnes and Noble? There must be a reason. Find out what it is and learn from it. Then go back to work and make the book better.And remember: Writing is a discipline that you can learn at any age. Unlike ballet or basketball or modeling, writing is not something that if you missed doing at 16, 18, or 20, you could never do again. You are NEVER too old to begin writing! I recall interviewing Pulitzer and Nobel Prize-winning author Pearl S. Buck once. It was late fall, 1971, and at the time she was living in Vermont Pearl S. Buck

Pearl S. BuckWe were talking on the phone, and suddenly she began describing her backyard and what she said was the first snow of the season.”You should see this, Ron. From my office window, I am watching a leisurely shower of white crystals floating, drifting, and landing softly onto a carpet of jade. I wish you could see it.”

“I do,” I said. “Thanks for showing me.” I never forgot that conversation with the first American female Nobel laureate. She was 79 and still writing.Finally, writing–as difficult as it is–should also be fun. When you turn a beautiful phrase or create a vivid scene, you should feel a little flutter in your heart, a shiver in your soul. If you do, that means you have struck an evocative chord with your writing. Nothing is more rewarding than that! Write On!