Ronald E. Yates's Blog, page 45

October 28, 2021

The Awful English Language

To conclude my series of posts on the English language in general and on rhetorical devices, oxymora, respecting the language, and writing well in particular, here is a post about how illogical and difficult it is to master the English language. As with those previous posts, this post was a handout I used to share with my journalism students when I was teaching at the University of Illinois. I hope you find it interesting, but most of all I hope that you will have pity on those poor souls who are faced with the unenviable task of learning English as a second or third language.

Let’s face it, Americans are notoriously inept when it comes to learning other languages. Unlike Europe, where many people speak several languages because dozens of nations with distinct tongues adjoin one another, the United States only has Canada to the North and Mexico to the South.

Spanish is the second most widely spoken language in the United States. So you would think it would make sense for us to learn Spanish. But how many of us have taken Spanish classes in high school (or even college) and can manage only such phrases as “Una Cerveza mas por favor” (one more beer, please) or “¿Como te llamas?” (What’s your name?)?

Then there is Canada—an English-speaking country, except for those French-speaking diehard traditionalists in places like Montreal. Okay, some Americans may argue that Canadians speak English weirdly, as in aboot rather than about and uutside rather than outside.

Nonetheless, Americans can travel to Canada and get along just fine without worrying about a significant language barrier. Cultural barriers are another matter, but I won’t go into those here.

Centuries ago, I took high school French, and I think the only phrase I still recall is: “Comment allez-vous aujourd’hui?” (How are you today?).

Later in life, I learned German, but only because I was based for almost three years in a small Bavarian town in a signals intelligence detachment, married a German woman, and minored in German at the University of Kansas. Later, I learned Japanese while living there almost ten years as a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. Then, I picked up some Spanish while working in Mexico, Central, and South America.

And that brings me to the purpose of this post. When I was teaching journalism as a professor at the University of Illinois, I used to spend part of a class talking about what I called “The Awful English Language.”

We Americans complain about learning other languages because we say they are hard to digest. But think about the non-English speaker who has to traverse the illogical and contradictory muddle that the English language is.

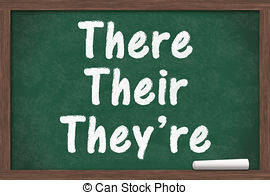

It is filled with homographs—words of like spelling that have more than one meaning. Then there are heterodoxies. That’s a homograph that is also pronounced differently.

Also, English tends to be a combination of prefixes, suffixes and borrowed words from several other languages. As a result, we end up with endless combinations of words with unpredictable, sometimes contradictory, meanings.

While some parts of the English language are relatively straightforward, such as the fact that nouns only have a single gender, it is the spelling and phonetics that often boggle the mind. There are so many silent letters – knock, knee, knight – and plurals that just don’t make sense.

The plural of ‘box’ is ‘boxes,’ yet the plural of ‘ox’ is ‘oxen,’ not ‘oxes.’ We see these arbitrary formations happen all the time in the English language, as well as words that sound similar yet are spelled differently, or sound the same but are used in different contexts.

Now for a brief homily about the English language and how it got so damned complicated. Ahem, bear with me, please.

The English language belongs to the West Germanic branch of the Indo-European family of languages but has been influenced over the centuries by many different languages. English is considered to be a “borrowing” language, and that is why it developed the complexity that non-English speakers and even we native speakers find frustrating today.

English can be categorized into three groups: Old English (or Anglo-Saxon), Middle English and Modern English.

The invasion of the three Germanic tribes (Saxons, Angles, and Jutes) who came to the British Isles in the fifth century A.D from places now known as Northwest Germany and the Netherlands significantly impacted the English language. Their dialects mixed with English throughout the years.

Danes and Norsemen, also called Vikings, later invaded the country. Hence, Old Norse and Latin words are also found in the English language. The Anglo-Norman French of the dominant class also profoundly influenced vocabulary after the Norman Conquest in 1066.

Hence, we have a mongrel language blended from dozens of tongues, dialects, and idioms.

There. That wasn’t so bad, was it?

Now, take a look at these gems and maybe then you will begin to pity the non-English speaker who must learn English.

The bandage was wound around the wound.The farm was used to produce produce.The dump was so full that it had to refuse more refuse.We must polish the Polish furniture.He could lead if he would get the lead out.The soldier decided to desert his dessert in the desert.Since there is no time like the present, he thought it was time to present the present.A bass was painted on the head of the bass drum.When shot at, the dove dove into the bushes.I did not object to the object.The insurance was invalid for the invalid.There was a row among the oarsmen about how to row.They were too close to the door to close it.The buck does funny things when the does are present.A seamstress and a sewer fell into a sewer line.To help with planting, the farmer taught his sow to sow.The wind was too strong to wind the sail.After a number of injections, my jaw got number.Upon seeing the tear in the painting, I shed a tear.I had to subject the subject to a series of tests.How can I intimate this to my most intimate friend?Why do our noses run but our feet smell?I did not object to the object.Freddie filled in his form by filling it out.Why do performers recite a play, yet play at a recital?Had enough? No? Then think about these conundrums of the English language.

If lawyers are disbarred, and clergymen defrocked, does it not follow that electricians can be delighted, musicians denoted, cowboys deranged, models deposed, or dry cleaners depressed?

Laundry workers could decrease, eventually becoming depressed and depleted.

Even more, bedmakers could be debunked, baseball players debased, landscapers deflowered, software engineers detested, underwear manufacturers debriefed, and even musical composers will eventually decompose.

On a different note, though, perhaps we can hope that some politicians will be devoted.

Yes, English is a crazy language. In fact, that was the title of a song that Pete Seeger used to sing years ago. Here are a few excerpts:

“English is the most widely spoken language in the history of the planet.

One out of every seven human beings can speak or read it.

Half the world’s books, 3/4 of the international mail are in English.

It has the largest vocabulary, perhaps two million words,

And a noble body of literature. But face it:

English is cuh-ray-zee!

There’s no egg in eggplant, no pine or apple in pineapple.

Quicksand works slowly; boxing rings are square.

A writer writes, but do fingers fing?

Hammers don’t ham, grocers don’t groce. Haberdashers don’t haberdash.

English is cuh-ray-zee!

If the plural of tooth is teeth, shouldn’t the plural of booth be beeth?

It’s one goose, two geese. Why not one moose, two meese?

If it’s one index, two indices; why not one Kleenex, two Kleenices?

English is cuh-ray-zee!

You can comb through the annals of history, but not just one annal.

You can make amends, but not just one amend.

If you have a bunch of odds and ends and get rid of all but one, is it an odd or an end?

If the teacher taught, why isn’t it true that a preacher praught?

If you wrote a letter, did you also bote your tongue?

And if a vegetarian eats vegetables, what does a humanitarian eat?

English is cuh-ray-zee!

If teachers taught, why didn’t preachers praught?

Why is it that night falls but never breaks and day breaks but never falls?

In what other language do people drive on the parkway and park on the driveway?

Ship by truck but send cargo by ship? Recite at a play but play at a recital?

Have noses that run and feet that smell?

English is cuh-ray-zee!

How can a slim chance and a fat chance be the same

When a wise man and a wise guy are very different?

To overlook something and to oversee something are very different,

But quite a lot and quite a few are the same.

How can the weather be hot as hell one day and cold as hell the next?

English is cuh-ray-zee!”

Of course English is a creation of humanity, not computers, and it reflects the creativity of the human race, which, of course, is not a race at all. That is why, when the stars are out, they are visible, but when the lights are out, they are invisible.

There are also dozens of illogical idioms we hear every day. Such as:

“Head over heels” (in love, for example). Surely the phrase should be “heels over head.”

“Meteoric rise” (to fame, for example). Meteors don’t rise. They fall.

“Quantum Leap” (meaning a significant change). A quantum leap is a very small change, but at least it is large on the scale of atoms.

“To leapfrog” over something. Surely it should be “frog leap” over.

He “turned up dead.” That’s used mainly in the US. Turning up, even when you are dead, takes real determination.

“Back-to-back” means consecutive, e.g., back-to-back wins. It should be “back-to-front,” I think. The end of one thing is followed by the start of the next thing and not the end of it. Unfortunately, “back-to-front” already has a different meaning.

Finally, there are these ten meaningless and irritating English clichés and expressions that should be banned forever. I cringe whenever I hear them, which is every day—especially by newsreaders and political pundits on television.

At the end of the dayAt this moment in timeThe bottom lineI personallyWith all due respectIt’s a nightmareFairly uniqueShouldn’t of (ouch!)24/7It’s not rocket science-PS: Why doesn’t ‘Buick’ rhyme with ‘quick’?

October 27, 2021

A Short Primer on Rhetorical Devices

This post is a continuation of my discussion of writing and the English language. Yesterday and Monday, I posted about oxymora and some tips about writing well. Both posts were based on handouts I used to give my students when I was teaching journalism at the University of Illinois. If you haven’t seen them, I urge you to take a look. Here is another handout I used to give my students. It deals with rhetorical devices and how to employ them in your writing. I hope you find it useful.

Style must be in harmony with content, and with the story’s purpose and audience. The best way—perhaps the only way to acquire a distinctive style is by reading and analyzing excellent writing. When this is done with care, you will begin to absorb into your language patterns, some useful techniques that will improve your writing.

Because style is a matter of emphasizing the essential parts of your subject—your facts or your feelings—remember that the most faithful servants of emphasis are surprise and variety. Too much surprise will exhaust readers, thus making them immune to it. But too much familiarity will bore them.

Though readers may be unaware of an article’s tone, remember that they are nevertheless affected by it, for tone is contagious. Therefore, take care to choose words that accurately convey your feelings about the subject at hand.

Finally, because laziness in word choice, staleness, and monotony are the enemies of style, a writer must occasionally let words cut unexpected capers. Writers must strive to remain unpredictable. If there is a secret of good writing, perhaps that is it.

A Glossary of Rhetorical Terms

Alliteration: The occurrence of words more or less in sequence having the same beginning sound. (“words that had warmed women, wooed and won them…”—Gay Telese).

Allusion: Reference to a well-known book, person, place, or event. Allusion is an economical way to enrich the impact of your writing with emotional and intellectual echoes from another work. (“If a [McDonald’s] manager tries to sell his customers hamburgers that have been off the grill more than 10 minutes…Big Brother in Oak Brook will find out.”—Time. Big Brother is a reference to the supreme authority in George Orwell’s 1984. “(The photograph) shocked the nation into realizing that something was rotten in Vietnam.”—John G. Morris. An allusion to Hamlet.

Anticlimax: A descent from a comparatively lofty vocabulary or tone to one noticeably less exalted. If the drop is sudden, the effect is often comic. (“Fun is for the frivolous, and Jimmy (Carter) sees the world as a hard and serious place. Man was put here to suffer, to atone, to repent, to confess, to surrender, to witness, or else to bake until well-did.” Larry L. King)

Antithesis: Figure of balance in which contrasting ideas are intentionally juxtaposed. (“The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.” President Lincoln. “We are caught in war, wanting peace. We’re torn by division, wanting unity.” President Nixon.

Connotation: The implications or suggestions evoked by a word. Connotations may be highly individual, based on associations because of pleasant or unpleasant experiences in a person’s life, or universal—that is, culturally conditioned.

Denotation: The literal meaning of a word, exclusive of attitudes or feelings the writer or speaker may have.

Hyperbole: Exaggeration as a means of achieving emphasis, humor, and sometimes irony. (“Here she [Ann Miller] stands for a moment, examining legs that start at the waist and end nine miles below in a pair of shoes she’s nicknamed Mac and Joe.”—Arthur Bell.

Imagery: In its most common use, imagery suggests visual detail or pictures, though it may also refer to words denoting other sensory experiences.

Irony: A discrepancy between what is said and what is meant; incongruity. Often used with a kind of grim humor, irony gives the effect of cool detachment and restraint. (“Carter…ignored the Democratic crown prince, Ted Kennedy, the well-known midnight aquanaut.”—Larry L. King)

Metaphor: A comparison of two unlike objects without using the word “like.” (“Sentimentality and repression have a natural affinity; they’re the two sides of one counterfeit coin.”—Pauline Kael. “A very old woman with gray hair is hauled along by her life-support system, a curly-haired blue-jacketed black dog on a leash.”—Talk of the Town, The New Yorker. Another example is Kenneth Tynan describing the stage relationship between TV’s Johnny Carson and comedian Don Rickles: “More deftly than anyone else, Carson knows how to play matador to Rickles’ bull, inciting him to charge, and sometimes getting gored himself.”)

Onomatopoeia: The use of words whose sounds seem to express or reinforce their meanings: hiss, bank, bow-wow, for example. (“The room clacked with the crack of billiard balls.”—Gay Telese.

Oxymoron: Two apparently contradictory terms that express a startling paradox. (“a smiling man-child of 51”—Shana Alexander; “flawless faux pas”—Arthur Bell)

Parallelism: Writing in which similar or related ideas are expressed in similar grammatical structure, thus achieving balance, rhythm, and emphasis. (Look for the series of parallel verb phrases at the end of this sentence: “It is strangely comforting to surrender an unadorned, eminently imperfect body to the ministration of another human being: someone who will rotate the stiffened joints, knead the balky muscles, unknot the drum-tight nerves and coax the sluggish skin into alertness.” Michelle Green. “So say what you will about Reggie Jackson: he knows how to heat up a house and how to ring down a curtain.” Mark Goodman)

Periodic Sentence: A suspenseful sentence, usually long, in which the main idea is not completed until the very end. (“Every four or eight years a large band of men, mostly without previous experience of government, mostly young, all dangerously euphoric because of recent and often accidental political success, all billed as geniuses by the Washington press corps and believing their own notices, all persuaded that they were meant by the stars to reinvent the wheel, are given great ostensible, and even actual, power on the White House staff.”—John Kenneth Galbraith.

Personification: A figure of speech in which inanimate objects or abstract ideas are endowed with human qualities. (“the shape and shade and size and noise of the words as they hummed, strummed, jigged and galloped along”—Dylan Thomas.

Pun: Wordplay involving the use of a word with two different meanings or the use of a word that is pronounced similarly to another with a different meaning. (“a science writer who can make the language of numbers sound as easy as pi”—Time. “McDonald’s is a super clean production machine efficient enough to give even the chiefs of General Motors food for thought.” Time)

Simile: An expressed comparison between two unlike objects. (Kenneth Tynan describing host Johnny Carson: “In repose, he resembles a king-sized ventriloquist’s dummy.” “The white flesh of her thighs rose like soft bread dough over the tops of her stockings.”—Stephanie Mills.)

Symbol: Something that represents something else by association, resemblance, or convention, especially a material object used to represent something invisible.

Zeugma: A construction in which one word is placed in the same grammatical relationship to two other words, but it relates to the two in different senses. Zeugma usually involves a verb and two objects, and the verb has two different meanings. (“He was a serious young man wearing glasses and the mien of a Harvard divinity student.”—Terry Southern)

— 30 —

October 26, 2021

Top 50 Oxymora: A List for Writers

In my ongoing posts about writing and the English language, here is another handout I shared with my students at the University of Illinois during my tenure there as a professor and dean. I hope you will find it useful.

An oxymoron is a figure of speech that combines two seemingly contradictory or opposite ideas to create a particular rhetorical or poetic effect and reveal a more profound truth. Generally, the ideas will come as two separate words placed side by side. The most common type of oxymoron is an adjective followed by a noun.

Oxymora (that’s the plural of oxymoron) are sometimes useful literary devices for writers. They are okay to use occasionally, but don’t overdo it! If you have read Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet you might recall this line which is a classic example of using an oxymoron in literature:

“Good night, good night! Parting is such sweet sorrow

That I shall say good night till it be morrow.”

Here is a list I used to give my journalism students at the University of Illinois. It is by no means exhaustive. This list is by no means comprehensive or complete. There are many more floating around out there. Enjoy!

Orderly confusionMinor crisisConfirmed rumorDeafening silenceKnown secretAct naturallyFound missingResident alienAdvanced BASICGenuine imitationAirline FoodGood griefSame differenceAlmost exactlyGovernment organizationSanitary landfillAlone togetherLegally drunkSilent screamLiving deadSmall crowdBusiness ethicsSoft rockButt-HeadMilitary IntelligenceSoftware documentationNew classicSweet sorrowChildproof“Now, then …”Synthetic natural gasPassive aggressionTaped liveClearly misunderstoodPeace forceExtinct LifeTemporary tax increaseComputer jockPlastic glassesTerribly pleasedComputer securityPolitical scienceTight slacksDefinite maybePretty uglyTwelve-ounce pound cakeDiet ice creamWorking vacationExact estimateMicrosoft WorksOctober 25, 2021

50 Tips on How to Write Good (Ahem)

As promised Saturday, here is another handout I used to give to my students when I was teaching journalism at the University of Illinois. I hope you find it useful. The contents of this post are an alphabetical arrangement of two lists that have been circulating among writers and editors for many years. In case you have missed out all this time, I’m sharing here the wit and wisdom of the late New York Times language maven William Safire and advertising executive and copywriter Frank LaPosta Visco.

1. A writer must not shift your point of view.

2. Always pick on the correct idiom.

3. Analogies in writing are like feathers on a snake.

4. Always be sure to finish what

5. Avoid alliteration. Always.

6. Avoid archaec spellings.

7. Avoid clichés like the plague. (They’re old hat.)

8. Avoid trendy locutions that sound flaky.

9. Be more or less specific.

10. Comparisons are as bad as clichés.

11. Contractions aren’t necessary.

12. Do not use hyperbole; not one in a million can do it effectively.

13. Don’t indulge in sesquipedalian lexicological constructions.

14. Don’t never use no double negatives.

15. Don’t overuse exclamation marks!!

16. Don’t repeat yourself, or say again what you have said before.

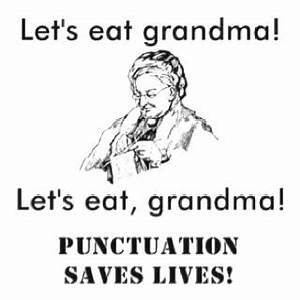

17. Don’t use commas, that, are not, necessary.

18. Don’t be redundant; don’t use more words than necessary; it’s highly superfluous.

19. Eliminate quotations. As Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “I hate quotations. Tell me what you know.”

20. Employ the vernacular.

21. Eschew ampersands & abbreviations, etc.

22. Eschew obfuscation.

23. Even if a mixed metaphor sings, it should be derailed.

24. Everyone should be careful to use a singular pronoun with singular nouns in their writing.

25. Exaggeration is a billion times worse than understatement.

26. Foreign words and phrases are not apropos.

27. Go around the barn at high noon to avoid colloquialisms.

28. Hopefully, you will use words correctly, irregardless of how others use them.

29. If any word is improper at the end of a sentence, a linking verb is.

30. If you reread your work, you can find on rereading a great deal of repetition can be avoided by rereading and editing.

31. It behooves you to avoid archaic expressions.

32. It is wrong to ever split an infinitive.

33. Never use a big word when a diminutive alternative would suffice.

34. No sentence fragments.

35. One should never generalize.

36. One-word sentences? Eliminate.

37. Parenthetical remarks (however relevant) are unnecessary.

38. Parenthetical words however must be enclosed in commas.

39. Place pronouns as close as possible, especially in long sentences, as of ten or more words, to their antecedents.

40. Placing a comma between subject and predicate, is not correct.

41. Poofread carefully to see if you any words out.

42. Prepositions are not words to end sentences with.

43. Profanity sucks.

44. Subject and verb always has to agree.

45. Take the bull by the hand and avoid mixing metaphors.

46. The adverb always follows the verb.

47. The passive voice is to be avoided.

48. Understatement is always best.

49. Use the apostrophe in it’s proper place and omit it when its not needed.

50. Use youre spell chekker to avoid mispeling and to catch typograhpical errers.

51. Who needs rhetorical questions?

52. Writing carefully, dangling participles must be avoided.

Oh, and let me add one tip: If your article consists of a list and the title refers to the number of items in the list, count the number of items in the list carefully. Hmmm. Did I forget something?

October 23, 2021

Respecting the Language: 80 Do’s and Don’ts

(When I was teaching journalism at the University of Illinois, I used to give this handout on Respecting the Language: 80 Do’s and Don’ts to the Reporting 400 class I taught. Students told me they found it helpful. Here it is for those of you who write or who are contemplating writing. The list, by no means complete, nevertheless contains words often misused by writers. What follows are a few of the worst offenders, with explanations for avoiding these common grammatical and syntactical traps. I hope you find it useful)

Accept, Except. ACCEPT: To receive or approve. EXCEPT: to omit or to object to, as a verb; with exclusion, as a preposition.Affect, Effect. Generally AFFECT is the verb; EFFECT is the noun. “The letter did not AFFECT the outcome.” But the “letter had a significant EFFECT.” AFFECT means to influence. EFFECT as a verb means to cause or bring about. Thus: “It is almost impossible to EFFECT change.”After and Following. As a preposition, AFTER is preferred. “He answered questions AFTER his speech.”Afterward, Afterwards. Use AFTERWARD. The dictionary allows the use of AFTERWARDS only as a second form. The same applies to TOWARD and TOWARDS.Aggravate and Irritate. The preferred meaning of AGGRAVATE is to make worse or intensify. IRRITATE means to displease. Allude, Elude. You ALLUDE to (or mention) a book. You ELUDE (or escape) a pursuer.All right. That’s the way to spell it. The dictionary may list ALRIGHT as a legitimate word but it is not acceptable in standard usage. Annual. Don’t use first with it. If it’s the first time, it can’t be ANNUAL.Anxious, Eager. ANXIOUS means worried; EAGER means desirous. Usually a person is EAGER to begin a vacation, not ANXIOUS.Apt, Liable, Likely. Preferred meaning of APT is appropriate–an APT remark. LIABLE means accountable; LIKELY means probably.At, In. AT refers to a point, so it’s better to say: He died IN the hospital.Averse, Adverse. If you don’t like something, you are AVERSE (or opposed) to it. ADVERSE is an adjective: ADVERSE (bad) weather, ADVERSE conditions.Bad, Badly. Don’t say: The boy had a BAD earache. Or: The man was injured BADLY. (Is there a “good” earache or injury?) Make it a SEVERE earache and injured SEVERELY. Because. Use it rather than DUE TO or OWING TO, both of which are stilted. “The game was cancelled BECAUSE of rain,” not DUE TO or OWING TO rain.Between, Among, Amongst. Something is shared BETWEEN two persons, AMONG three or more. AMONG is always better than AMONGST, which is archaic.Block, Bloc. A BLOC is a coalition of persons or a group with the same purpose or goal. Don’t call it a BLOCK, which has some 40 dictionary definitions.Burglary, Robbery, and Holdup. BURGLARY means to enter a building with intent to commit a felony. ROBBERY is to take property from a person with force or threat of force. HOLDUP is a synonym for ROBBERY or ARMED ROBBERY, but NOT for BURGLARY.Capital, Capitol. CAPITAL is the city; CAPITOL the building.Claim. Don’t use CLAIM for SAID or INSIST. CLAIM means to assert ownership: He CLAIMED his book.Collide, Strike. For there to be a COLLISION, both objects must be in motion. So, two moving cars COLLIDE, but a car STRIKES a tree.Common, Mutual. Jones and Smith have a COMMON dislike for Allen. (Allen may not even be aware of it.) Cooke and Brown have a MUTUAL dislike for each other. The feeling is reciprocal.Compose, Comprise, Include. You COMPOSE things by putting them together. Once the parts are put together, the object COMPRISES or INCLUDES or embraces the parts. Comprise is used in the active voice: A knife, fork and spoon COMPRISE the set. COMPOSE is used in the passive voice. The set is COMPOSED of knife, fork and spoon. INCLUDE, preferably, not all parts of the whole: The set INCLUDES a knife and fork.Continual, Continuous. CONTINUAL means recurring at brief intervals but never really stopping. CONTINUOUS means to occur without any interruption at all.Couple of. You need the OF. It’s never “a couple tomatoes.”Dates from. Something DATES from, not BACK to.Demolish, Destroy. They mean to do away with completely. You can’t partially DEMOLISH or DESTROY something, nor is there any need to say totally DESTROYED.Deny, Refute. DENY has two preferred meanings: (1) to withhold something and (2) simply a negative response to an accusation. REFUTE means to destroy an argument, either by reasoning alone or with evidence; a fairly close synonym for DISPROVE, but not for DENY.Different from. Things and people are different FROM each other. Don’t write that they are different THAN each other.Drown, Drowned. Don’t say someone was DROWNED unless an assailant held the victim’s head underwater. Just say the victim DROWNED.Ecology, Environment. They are NOT synonymous. ECOLOGY is the study of the relationship between organisms and their ENVIRONMENT.

RIGHT

: “The laboratory is studying the ECOLOGY of man and the desert.”

WRONG

: “Even so simple an undertaking as maintaining a lawn affects ECOLOGY. RIGHT: “Even so simple an undertaking as maintaining a lawn affects our ENVIRONMENT.

Because. Use it rather than DUE TO or OWING TO, both of which are stilted. “The game was cancelled BECAUSE of rain,” not DUE TO or OWING TO rain.Between, Among, Amongst. Something is shared BETWEEN two persons, AMONG three or more. AMONG is always better than AMONGST, which is archaic.Block, Bloc. A BLOC is a coalition of persons or a group with the same purpose or goal. Don’t call it a BLOCK, which has some 40 dictionary definitions.Burglary, Robbery, and Holdup. BURGLARY means to enter a building with intent to commit a felony. ROBBERY is to take property from a person with force or threat of force. HOLDUP is a synonym for ROBBERY or ARMED ROBBERY, but NOT for BURGLARY.Capital, Capitol. CAPITAL is the city; CAPITOL the building.Claim. Don’t use CLAIM for SAID or INSIST. CLAIM means to assert ownership: He CLAIMED his book.Collide, Strike. For there to be a COLLISION, both objects must be in motion. So, two moving cars COLLIDE, but a car STRIKES a tree.Common, Mutual. Jones and Smith have a COMMON dislike for Allen. (Allen may not even be aware of it.) Cooke and Brown have a MUTUAL dislike for each other. The feeling is reciprocal.Compose, Comprise, Include. You COMPOSE things by putting them together. Once the parts are put together, the object COMPRISES or INCLUDES or embraces the parts. Comprise is used in the active voice: A knife, fork and spoon COMPRISE the set. COMPOSE is used in the passive voice. The set is COMPOSED of knife, fork and spoon. INCLUDE, preferably, not all parts of the whole: The set INCLUDES a knife and fork.Continual, Continuous. CONTINUAL means recurring at brief intervals but never really stopping. CONTINUOUS means to occur without any interruption at all.Couple of. You need the OF. It’s never “a couple tomatoes.”Dates from. Something DATES from, not BACK to.Demolish, Destroy. They mean to do away with completely. You can’t partially DEMOLISH or DESTROY something, nor is there any need to say totally DESTROYED.Deny, Refute. DENY has two preferred meanings: (1) to withhold something and (2) simply a negative response to an accusation. REFUTE means to destroy an argument, either by reasoning alone or with evidence; a fairly close synonym for DISPROVE, but not for DENY.Different from. Things and people are different FROM each other. Don’t write that they are different THAN each other.Drown, Drowned. Don’t say someone was DROWNED unless an assailant held the victim’s head underwater. Just say the victim DROWNED.Ecology, Environment. They are NOT synonymous. ECOLOGY is the study of the relationship between organisms and their ENVIRONMENT.

RIGHT

: “The laboratory is studying the ECOLOGY of man and the desert.”

WRONG

: “Even so simple an undertaking as maintaining a lawn affects ECOLOGY. RIGHT: “Even so simple an undertaking as maintaining a lawn affects our ENVIRONMENT.

Either. It means one or the other, not both.

WRONG

: “There were lions on either side of the door.”

RIGHT

: “There were lions on EACH side of the door.”Entrant and Entry. If you’re referring to a participant in a contest, ENTRANT is preferred.Farther, Further. Both can be applied to distance, but only FURTHER can be used in reference to ideas or degree. Examples: “They walked FARTHER or FURTHER into the forest. They will make a FURTHER study of the problem.Fewer, Less. Fewer applies to numbers; less to amount or bulk. You eat fewer grapes, but less meat. If you can separate items in the quantities being compared, use FEWER. If not, use LESS.

WRONG

: The 49ers are inferior to the Chiefs because they have LESS fast receivers.

RIGHT

: The 49ers are inferior to the Chiefs because they have FEWER fast receivers.

RIGHT

: The 49ers are inferior to the Chiefs because they have LESS speed.Fliers, Flyers. Pilots are FLIERS. Handbills are FLYERS.Flout, Flaunt. They aren’t the same words; they mean completely different things and they’re very commonly confused. FLOUT means to mock, to scoff or to show disdain for. FLAUNT means to display ostentatiously.Funeral service. A redundant expression. A FUNERAL is a service.Get, Obtain, Secure. GET and OBTAIN are synonyms: GET or OBTAIN a book from your friend. SECURE has two preferred meanings: To make FAST, like a door; or to SECURE a loan.Heart Attack, Heart Failure. A person dies of a HEART ATTACK or HEART DISEASE, not HEART FAILURE.Head up. People don’t HEAD UP committees. They HEAD them.Hopefully. Hope. One of the most commonly misused words, in spite of what the dictionary may say. HOPEFULLY should describe the way a subject FEELS. For example: HOPEFULLY, I shall present the plan to the president. (This means I will be HOPEFUL when I do it.) But it is something else again when you attribute hope to a non-person. You may write: HOPEFULLY, the war will end soon. You may mean you HOPE the war will end soon, but it is not what you are writing. What you should write is: I HOPE the war will end soon.Imply, Infer. The speaker IMPLIES; the listener INFERS.In Advance, Prior To. Use BEFORE; it sounds more natural.It’s, Its. ITS is the possessive; IT’S is the contraction of IT IS.

WRONG

: What is IT’S name?

RIGHT

: What is ITS name? ITS name is Fido.

RIGHT

: IT’S the first time he’s talked tonight

RIGHT

: IT’S my coat.Last, Latest. LAST: There won’t be any more. LATEST: The most recent of a probable series.Lay, Lie. LAY, LAID, LAID; Transitive, taking an object. “I will LAY the book on the table.” LIE, LAY, LAIN; intransitive, no object. “The tired boy LAY on the porch yesterday.” Leave, Let. LEAVE ALONE means to depart from or cause to be in solitude. LET ALONE means to be undisturbed.

WRONG

: The man pulled a gun on her but Jones intervened and talked him into LEAVING HER ALONE. RIGHT: The man pulled a gun on her but Jones intervened and talked him into LETTING HER ALONE. RIGHT: “When I entered the room I saw that Jim and Mary were sleeping so I decided to LEAVE THEM ALONE.Lend, Loan as verbs. Preferred usage: LOAN applies to money; LEND, to other objects.Like, As. Don’t use LIKE for AS or AS IF. In general, use LIKE to compare with nouns and pronouns; use AS when comparing with phrases and clauses that contain a verb.

WRONG

: Jim blocks the linebacker LIKE he should. RIGHT: Jim blocks the linebacker AS he should.

RIGHT

: Jim blocks LIKE a pro. And PLEASE control the juvenile urge to use LIKE as some kind of a crutch in a sentence: “It was, LIKE, really cool” or “Then, we LIKE, went to Urbana.” Arrgghhh.Locate, Situate. A new house will be LOCATED at a certain address. Once built, it is SITUATED there. Another meaning of LOCATE is to find something for which you have been looking.Marshall, Marshal. Generally, the first form is correct only when the word is a proper noun: John MARSHALL. The second form is the verb form: Marilyn will MARSHAL her forces. And the second form is the one to use for a title: FIRE MARSHAL Stan Anderson; DEPUTY MARSHAL Wyatt Earp; FIELD MARSHAL Erwin Rommel.Media. MEDIA is the plural of MEDIUM. The MEDIA are, not is.

Either. It means one or the other, not both.

WRONG

: “There were lions on either side of the door.”

RIGHT

: “There were lions on EACH side of the door.”Entrant and Entry. If you’re referring to a participant in a contest, ENTRANT is preferred.Farther, Further. Both can be applied to distance, but only FURTHER can be used in reference to ideas or degree. Examples: “They walked FARTHER or FURTHER into the forest. They will make a FURTHER study of the problem.Fewer, Less. Fewer applies to numbers; less to amount or bulk. You eat fewer grapes, but less meat. If you can separate items in the quantities being compared, use FEWER. If not, use LESS.

WRONG

: The 49ers are inferior to the Chiefs because they have LESS fast receivers.

RIGHT

: The 49ers are inferior to the Chiefs because they have FEWER fast receivers.

RIGHT

: The 49ers are inferior to the Chiefs because they have LESS speed.Fliers, Flyers. Pilots are FLIERS. Handbills are FLYERS.Flout, Flaunt. They aren’t the same words; they mean completely different things and they’re very commonly confused. FLOUT means to mock, to scoff or to show disdain for. FLAUNT means to display ostentatiously.Funeral service. A redundant expression. A FUNERAL is a service.Get, Obtain, Secure. GET and OBTAIN are synonyms: GET or OBTAIN a book from your friend. SECURE has two preferred meanings: To make FAST, like a door; or to SECURE a loan.Heart Attack, Heart Failure. A person dies of a HEART ATTACK or HEART DISEASE, not HEART FAILURE.Head up. People don’t HEAD UP committees. They HEAD them.Hopefully. Hope. One of the most commonly misused words, in spite of what the dictionary may say. HOPEFULLY should describe the way a subject FEELS. For example: HOPEFULLY, I shall present the plan to the president. (This means I will be HOPEFUL when I do it.) But it is something else again when you attribute hope to a non-person. You may write: HOPEFULLY, the war will end soon. You may mean you HOPE the war will end soon, but it is not what you are writing. What you should write is: I HOPE the war will end soon.Imply, Infer. The speaker IMPLIES; the listener INFERS.In Advance, Prior To. Use BEFORE; it sounds more natural.It’s, Its. ITS is the possessive; IT’S is the contraction of IT IS.

WRONG

: What is IT’S name?

RIGHT

: What is ITS name? ITS name is Fido.

RIGHT

: IT’S the first time he’s talked tonight

RIGHT

: IT’S my coat.Last, Latest. LAST: There won’t be any more. LATEST: The most recent of a probable series.Lay, Lie. LAY, LAID, LAID; Transitive, taking an object. “I will LAY the book on the table.” LIE, LAY, LAIN; intransitive, no object. “The tired boy LAY on the porch yesterday.” Leave, Let. LEAVE ALONE means to depart from or cause to be in solitude. LET ALONE means to be undisturbed.

WRONG

: The man pulled a gun on her but Jones intervened and talked him into LEAVING HER ALONE. RIGHT: The man pulled a gun on her but Jones intervened and talked him into LETTING HER ALONE. RIGHT: “When I entered the room I saw that Jim and Mary were sleeping so I decided to LEAVE THEM ALONE.Lend, Loan as verbs. Preferred usage: LOAN applies to money; LEND, to other objects.Like, As. Don’t use LIKE for AS or AS IF. In general, use LIKE to compare with nouns and pronouns; use AS when comparing with phrases and clauses that contain a verb.

WRONG

: Jim blocks the linebacker LIKE he should. RIGHT: Jim blocks the linebacker AS he should.

RIGHT

: Jim blocks LIKE a pro. And PLEASE control the juvenile urge to use LIKE as some kind of a crutch in a sentence: “It was, LIKE, really cool” or “Then, we LIKE, went to Urbana.” Arrgghhh.Locate, Situate. A new house will be LOCATED at a certain address. Once built, it is SITUATED there. Another meaning of LOCATE is to find something for which you have been looking.Marshall, Marshal. Generally, the first form is correct only when the word is a proper noun: John MARSHALL. The second form is the verb form: Marilyn will MARSHAL her forces. And the second form is the one to use for a title: FIRE MARSHAL Stan Anderson; DEPUTY MARSHAL Wyatt Earp; FIELD MARSHAL Erwin Rommel.Media. MEDIA is the plural of MEDIUM. The MEDIA are, not is.

Mean, Average, Median. Use MEAN as synonymous with AVERAGE. Each word refers to the sum of all components divided by the number of components. MEDIAN is the number that has as many components above it as below it–it is the middle value in a distribution of items, the point at which half of the items are above and half below. MEAN is the statisticians’ language for AVERAGE.Nouns. There is a growing trend toward using them as verbs. Resist it. HOST, HEADQUARTERS and AUTHOR, for example, are nouns; even though the dictionary may acknowledge they can be used as verbs. If you do, you’ll come up with a monstrosity such as: “HEADQUARTERED at his country home, John Doe HOSTED a party to celebrate the book he had just AUTHORED.” Again, Arrgghhh!Odd, Peculiar. ODD means strange or unusual; PECULIAR means distinctive to one person or one group, etc.Of, With, From. A woman is ill OF a disease, not WITH. She dies OF the disease, not FROM it.Oral, Verbal. Use ORAL when use of the mouth is central to the thought; the word emphasizes the idea of human utterance. VERBAL may apply to spoken or written words; it connotes the process of reducing ideas to writing. Usually, it’s a VERBAL contract, not an ORAL one, if it’s in writing.Over and More Than. They aren’t interchangeable. OVER refers to spatial relationships: The plane flew OVER the city. MORE THAN is used with figures: In the crowd were MORE THAN 1,000 fans. Make it MORE THAN 20 persons, not OVER. MORE THAN means in excess of; OVER means physically above.Parallel Construction. Thoughts in series in the same sentence require PARALLEL construction.

WRONG

: The union delivered demands for an increase of 10 percent in wages and to cut the workweek to 30 hours. RIGHT: The union delivered demands for an increase of 10 percent in wages and for a REDUCTION in the workweek to 30 hours.Part and Portion. When one is referring to a fragment of the whole, PART is preferred. PORTION more specifically means a serving of food.Peddle, Pedal. When selling something, you PEDDLE it. When riding a bicycle or similar form of locomotion, you PEDAL it.

Mean, Average, Median. Use MEAN as synonymous with AVERAGE. Each word refers to the sum of all components divided by the number of components. MEDIAN is the number that has as many components above it as below it–it is the middle value in a distribution of items, the point at which half of the items are above and half below. MEAN is the statisticians’ language for AVERAGE.Nouns. There is a growing trend toward using them as verbs. Resist it. HOST, HEADQUARTERS and AUTHOR, for example, are nouns; even though the dictionary may acknowledge they can be used as verbs. If you do, you’ll come up with a monstrosity such as: “HEADQUARTERED at his country home, John Doe HOSTED a party to celebrate the book he had just AUTHORED.” Again, Arrgghhh!Odd, Peculiar. ODD means strange or unusual; PECULIAR means distinctive to one person or one group, etc.Of, With, From. A woman is ill OF a disease, not WITH. She dies OF the disease, not FROM it.Oral, Verbal. Use ORAL when use of the mouth is central to the thought; the word emphasizes the idea of human utterance. VERBAL may apply to spoken or written words; it connotes the process of reducing ideas to writing. Usually, it’s a VERBAL contract, not an ORAL one, if it’s in writing.Over and More Than. They aren’t interchangeable. OVER refers to spatial relationships: The plane flew OVER the city. MORE THAN is used with figures: In the crowd were MORE THAN 1,000 fans. Make it MORE THAN 20 persons, not OVER. MORE THAN means in excess of; OVER means physically above.Parallel Construction. Thoughts in series in the same sentence require PARALLEL construction.

WRONG

: The union delivered demands for an increase of 10 percent in wages and to cut the workweek to 30 hours. RIGHT: The union delivered demands for an increase of 10 percent in wages and for a REDUCTION in the workweek to 30 hours.Part and Portion. When one is referring to a fragment of the whole, PART is preferred. PORTION more specifically means a serving of food.Peddle, Pedal. When selling something, you PEDDLE it. When riding a bicycle or similar form of locomotion, you PEDAL it.

Pretense, Pretext. They’re different, but it’s a tough distinction. A PRETEXT is that which is put forward to conceal a truth. He was discharged for tardiness, but this was only a PRETEXT for general incompetence. A PRETENSE is a “false show;” a more overt act intended to conceal personal feelings. My profuse compliments were all PRETENSE.Principle, Principal. A guiding rule or basic truth is a PRINCIPLE. The first, dominant, or leading thing is PRINCIPAL. PRINCIPLE is a noun; PRINCIPAL may be a noun or an adjective.Receive, Suffer, Sustain. Make it SUFFER an injury. You can use RECEIVE, but the preferred word is SUFFER. RECEIVING and injury implies that it was a gift, which most injuries are not. The preferred meanings of SUSTAIN are to support, such as an army; or to maintain, as to SUSTAIN a drive from the 50-yard line to the opponent’s goal line.Redundancies to Avoid:Easter Sunday, Make it EASTERIncumbent Congressman. CONGRESSMAN.Owns his own home. OWNS HIS HOME.The company will close down. THE COMPANY WILL CLOSE.Jones, Smith, Johnson and Reid were all convicted. Jones, Smith, Johnson and Reid WERE CONVICTED.Jewish rabbi. Just RABBI.8 p.m. tonight. All you need is 8 TONIGHT or 8 p.m. TODAY.During the winter months. DURING THE WINTER.Both Reid and Jones were denied pardons. Reid and Jones WERE DENIED PARDONS.I am currently tired. I AM TIRED.Autopsy to determine the cause of death. AUTOPSY (that’s what an AUTOPSY does). Refuse and Reject. The official REJECTED the request, not REFUSED the request. In this usage, REFUSE needs the infinitive of another verb: The official REFUSED TO GRANT the request. Refute. (See DENY). Reluctant, Reticent. If he doesn’t want to act, he is RELUCTANT. If he doesn’t want to speak, he is RETICENT. Say, Said. The most serviceable words in the journalist’s lexicon are the forms of the verb TO SAY. Let a person SAY something, rather than DECLARE or ADMIT or POINT OUT. And NEVER let him grin, smile, frown or giggle something.Sewage, Sewerage. SEWAGE means the contents of a sewer, but the community depends upon a SEWERAGE system. Temperatures. They may get higher or lower, but they don’t get WARMER or COOLER. WRONG: TEMPERATURES are expected to warm up in the area Friday. RIGHT: TEMPERATURES are expected to RISE in the area Friday. That, Which. THAT tends to restrict the reader’s thought and direct it the way you want it to go; WHICH is nonrestrictive, introducing a bit of subsidiary information. For Example: The lawnmower THAT is in the garage needs sharpening. (Meaning, we have more than one lawnmower. The one in the garage needs sharpening.) The lawnmower, WHICH is in the garage, needs sharpening. (Meaning: Our lawnmower needs sharpening. It is in the garage.) The statue, WHICH graces our entry hall, is on loan. (Meaning: Our statue is on loan. It happens to be in the entry hall.) Note that WHICH clauses take commas, signaling they are not essential to the meaning of the sentence.

Pretense, Pretext. They’re different, but it’s a tough distinction. A PRETEXT is that which is put forward to conceal a truth. He was discharged for tardiness, but this was only a PRETEXT for general incompetence. A PRETENSE is a “false show;” a more overt act intended to conceal personal feelings. My profuse compliments were all PRETENSE.Principle, Principal. A guiding rule or basic truth is a PRINCIPLE. The first, dominant, or leading thing is PRINCIPAL. PRINCIPLE is a noun; PRINCIPAL may be a noun or an adjective.Receive, Suffer, Sustain. Make it SUFFER an injury. You can use RECEIVE, but the preferred word is SUFFER. RECEIVING and injury implies that it was a gift, which most injuries are not. The preferred meanings of SUSTAIN are to support, such as an army; or to maintain, as to SUSTAIN a drive from the 50-yard line to the opponent’s goal line.Redundancies to Avoid:Easter Sunday, Make it EASTERIncumbent Congressman. CONGRESSMAN.Owns his own home. OWNS HIS HOME.The company will close down. THE COMPANY WILL CLOSE.Jones, Smith, Johnson and Reid were all convicted. Jones, Smith, Johnson and Reid WERE CONVICTED.Jewish rabbi. Just RABBI.8 p.m. tonight. All you need is 8 TONIGHT or 8 p.m. TODAY.During the winter months. DURING THE WINTER.Both Reid and Jones were denied pardons. Reid and Jones WERE DENIED PARDONS.I am currently tired. I AM TIRED.Autopsy to determine the cause of death. AUTOPSY (that’s what an AUTOPSY does). Refuse and Reject. The official REJECTED the request, not REFUSED the request. In this usage, REFUSE needs the infinitive of another verb: The official REFUSED TO GRANT the request. Refute. (See DENY). Reluctant, Reticent. If he doesn’t want to act, he is RELUCTANT. If he doesn’t want to speak, he is RETICENT. Say, Said. The most serviceable words in the journalist’s lexicon are the forms of the verb TO SAY. Let a person SAY something, rather than DECLARE or ADMIT or POINT OUT. And NEVER let him grin, smile, frown or giggle something.Sewage, Sewerage. SEWAGE means the contents of a sewer, but the community depends upon a SEWERAGE system. Temperatures. They may get higher or lower, but they don’t get WARMER or COOLER. WRONG: TEMPERATURES are expected to warm up in the area Friday. RIGHT: TEMPERATURES are expected to RISE in the area Friday. That, Which. THAT tends to restrict the reader’s thought and direct it the way you want it to go; WHICH is nonrestrictive, introducing a bit of subsidiary information. For Example: The lawnmower THAT is in the garage needs sharpening. (Meaning, we have more than one lawnmower. The one in the garage needs sharpening.) The lawnmower, WHICH is in the garage, needs sharpening. (Meaning: Our lawnmower needs sharpening. It is in the garage.) The statue, WHICH graces our entry hall, is on loan. (Meaning: Our statue is on loan. It happens to be in the entry hall.) Note that WHICH clauses take commas, signaling they are not essential to the meaning of the sentence.

Toward and Towards. Toward is preferred. Try and, Try To. Only TRY TO is correct. He will TRY TO score 20 points; not TRY AND score 20 points. The term TRY AND preceding another verb is wholly superfluous: the AND makes the second verb one of accomplishment, so why TRY? Under way, NOT Underway. But don’t say something got under way. Say it STARTED or BEGAN. Unique. Something that is unique is the only one of its kind. It can’t be VERY UNIQUE or QUITE UNIQUE or SOMEWHAT UNIQUE or RATHER UNIQUE. Don’t use it unless you really mean UNIQUE. UP. Don’t use it with a verb.

WRONG

: The manager said he would UP the price next week.

RIGHT

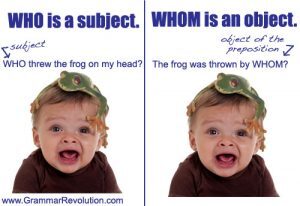

: The manager said he would RAISE the price next week. Who, Whom. A tough one, but generally you’re safe to use WHOM to refer to someone who has been the subject of an action. WHO is the word when the somebody has been the actor. EXAMPLE: A 20-year-old woman, to WHOM the room was rented, left the window open. A 20-year-old woman, WHO rented the room, left the window open. Who’s, Whose. Though it incorporates an apostrophe, WHO’S is NOT a possessive. It’s a contraction for WHO IS. WHOSE is the possessive.

WRONG

: I don’t know WHO’S coat it is.

RIGHT:

I don’t know WHOSE coat it is.

RIGHT

: Find out WHO’S there. Would. Be careful about using WOULD when constructing a conditional past tense.

WRONG

: If Soderholm WOULD NOT HAVE HAD an injured foot, Thompson wouldn’t have been in the lineup.

RIGHT

: If Soderholm HAD NOT HAD an injured foot, Thompson wouldn’t have been in the lineup.

Toward and Towards. Toward is preferred. Try and, Try To. Only TRY TO is correct. He will TRY TO score 20 points; not TRY AND score 20 points. The term TRY AND preceding another verb is wholly superfluous: the AND makes the second verb one of accomplishment, so why TRY? Under way, NOT Underway. But don’t say something got under way. Say it STARTED or BEGAN. Unique. Something that is unique is the only one of its kind. It can’t be VERY UNIQUE or QUITE UNIQUE or SOMEWHAT UNIQUE or RATHER UNIQUE. Don’t use it unless you really mean UNIQUE. UP. Don’t use it with a verb.

WRONG

: The manager said he would UP the price next week.

RIGHT

: The manager said he would RAISE the price next week. Who, Whom. A tough one, but generally you’re safe to use WHOM to refer to someone who has been the subject of an action. WHO is the word when the somebody has been the actor. EXAMPLE: A 20-year-old woman, to WHOM the room was rented, left the window open. A 20-year-old woman, WHO rented the room, left the window open. Who’s, Whose. Though it incorporates an apostrophe, WHO’S is NOT a possessive. It’s a contraction for WHO IS. WHOSE is the possessive.

WRONG

: I don’t know WHO’S coat it is.

RIGHT:

I don’t know WHOSE coat it is.

RIGHT

: Find out WHO’S there. Would. Be careful about using WOULD when constructing a conditional past tense.

WRONG

: If Soderholm WOULD NOT HAVE HAD an injured foot, Thompson wouldn’t have been in the lineup.

RIGHT

: If Soderholm HAD NOT HAD an injured foot, Thompson wouldn’t have been in the lineup.Check back Monday for another primer on writing. This one is entitled: “50 Tips on How to Write Good (Ahem)”

October 20, 2021

The Leftist Mantra: We Have to Destroy the Country to Save it

Anybody who covered the Vietnam War, as I did, became familiar with several phrases that were used to explain or clarify American involvement.

Terms like “Body Count,” “Hearts and Minds,” “Pacification,” “The light at the end of the tunnel,” come immediately to mind.

But there was another phrase that with just a few alterations seems to define what is happening in our country today. That phrase is “We had to destroy the village to save it.”

It is still used today to describe the brutal absurdities of war and the destructive extremes American forces went to annihilate the Communist Viet Cong who had taken refuge in the South Vietnamese village of Ben Tre in the Mekong Delta.

During the battle American bombs, rockets and napalm obliterated much of the town, hundreds of innocent civilians were killed, and most of the buildings were leveled. After the battle, a U.S. major allegedly justified the carnage by telling a U.S. reporter: “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.” In other words, the only way to kill the Viet Cong enemy was to destroy everybody and everything around them.

The Village of Ben Tre after the battle

The Village of Ben Tre after the battleWhen I watch what is happening today in America’s political universe the phrase that comes to mind is this: “We have to destroy the country to save it.”

It seems to be the justification for the perpetual war the Democrat party and the leftists that control waged against former President Trump and anybody who supported his agenda.

During the Trump administration, the concept of a “loyal opposition” disappeared completely. Do Americans even remember what a loyal opposition is? I sincerely doubt it.

A loyal opposition implies that a party that doesn’t hold the presidency or a majority in the House or Senate can still oppose the actions of the sitting president and the majority party while remaining loyal to the source of the government’s power—our constitutional form of government. In other words, they will not mount a Coup d’état to overthrow the government or impeach a president they don’t like. They will wait for the next election so the electorate can vote the rascals out.

This is what we see happening now with the Republican Party. While Republicans oppose Biden’s $3.5 trillion socialist spending plan I haven’t heard anybody in the GOP yelling for Biden’s impeachment–though it certainly seems plausible that they should given Biden’s horrific performance on our southern border, his mismanagement of the economy, the worst inflation in a decade, and the catastrophic (some might say criminal) exodus from Afghanistan.

Just how does a loyal opposition work, you might ask? Here’s a prime example. During World War II the Democrat Party held the office of president and the Republican Party cooperated fully and without reservation in FDR’s war effort.

In the past, we also saw this form of loyalty play out in the Senate judiciary committee when senators from both sides often voted for a judicial candidate without the kind of political rancor we see today. For example, during Ronald Reagan’s presidency, three of his nominees were approved unanimously (Sandra Day O’Connor, 99-0; Antonin Scalia, 98-0; and Anthony Kennedy, 97-0); Ruth Bader Ginsburg was approved during the Clinton presidency by a vote of 96-3.

Let’s look at the current justices and the votes they received. Clarence Thomas was approved in 1991 by the vote of 52-48; Stephen Breyer was approved in 1994, by a vote of 87-9; John Roberts, in 2005 by a vote of 78-22; Samuel Alito, 2006, 58-42; Sonia Sotomayor, 2009, 68-31; Elena Kagan, 2010, 63-37; Neil Gorsuch, 2017, 54-45; Eric Kavanaugh, 2018, 50-48; and Amy Coney Barrett, 2020, 52-48.

Given the clear partisan trend in approving Supreme Court Justices I think we can safely say that from this day forward, Supreme Court Justices will have to go through seven levels of hell to attain a seat on the nation’s highest court. The confirmation process is no longer about who is best qualified, who has the best legal mind, who can be the best justice, but what political party he or she belongs to and whether they are liberal, judicial activists, conservative or strict constructionists. In other words, it has evolved into a form of political combat; a kind of survival of the fittest.

Justice Kavanaugh

Justice KavanaughAfter the disgraceful displays of partisan politics regarding Judge Kavanaugh, if Democrats believe one of their future nominees will fly right through the confirmation process the way Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, or Kagan did they are sadly mistaken. There are long memories in the Senate and the way the last two Trump nominees have been treated means the Democrats are in for some severe retribution.

It’s a sad state of affairs.

The same can be said for the demented and frenzied opposition to President Trump, his cabinet, and his supporters, all of whom have been called the coarsest and most offensive of names—from “deplorables” and racists to Nazis and Fascists by the alleged “loyal opposition.”

The leftists and socialists that appear to be running the Democrat party are intent on turning our republic into a socialist ghetto. Never mind that socialism has failed in every country where it has been tried.

For some inane reason, there are people on the left who want to subject our highly successful capitalist republic to a form of government that eliminates incentive and profit and instead creates a system that says “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs”—the highly flawed philosophy of Marxism.

Why? It’s the “we have to destroy the country to save it” argument.

During the Trump administration, the mantra was, “Get rid of President Trump at any cost—even by death if necessary.” (Yes, people on the actually said that, and some, like goofy Maxine Waters, have come close to saying it).

That’s where we are today. Keep Republicans out of the White House, the Senate, and the House, even if it means destroying our republic and rebuilding it again, preferably in the image of Karl Marx.

So villagers take heed. Watch out for the political napalm, the socialist rockets, and the leftist bombs as we approach the 2022 midterm elections. The barrage from the socialist left has only just begun, and our country just may not survive the onslaught.

October 19, 2021

Our Disastrous Decline of Shared Prudence into Social Anarchy

Most of us have received one of those emails displaying photos of so-called “Walmart People.” As you scroll down, there is a collection of pictures of Walmart shoppers wearing wild assortments of clothing covering bodies that seem fashioned from silly putty or carved from tree stumps.

There are horribly overweight women wearing skimpy shorts barely covering explosions of tattoo-blemished buttock flesh. There are men wearing pink leotards and combat boots. There are people who seem to have crawled out of a fissure in the earth–troglodytes perhaps? Or conceivably, humanoid-like creatures from another planet that crash-landed into a Goodwill warehouse?

Can any of this be real? Do people look like that? And do they go to Walmart and other places?

The answer is yes, yes, and yes. These are real people. They do look like that, and they all too often abandon their dank and murky grottos to venture into well-lit public places such as Walmart.

What happened? How did our nation spawn organisms that apparently have no concept of taste, style, or class?

Beyond these “Walmart people” I think national taste and style hit a new low when the Northwestern University women’s 2005 national championship lacrosse team showed up at the White House wearing flip flops. What does this say about respect for the nation’s highest office, let alone personal pride and class?

It says none of that matters anymore. It says if you want to go to a funeral wearing cargo shorts and a tank top it’s OK because the most important thing is not showing a modicum of respect for the deceased, but how YOU feel.

The whole concept of “class” or what it means to be classy is an unknown quality with too many people today. Nothing is left to the imagination. In movies today it has become de rigueur for the camera to pass through the bedroom door as actors and actresses engage in multiple forms of mattress gymnastics.

Remember movies when a couple would go through a door, and then the next scene would be the next day? Isn’t that enough? Can’t we leave something to the imagination for God’s sake?

Can you imagine Katherine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Audrey Hepburn, Rita Hayworth, etc. baring it all for a scene with a nude Cary Grant, Gary Cooper, James Stewart or Burt Lancaster? Wouldn’t have happened. And it’s not just because the censors in those days would not have allowed it to happen. It’s because once upon a time Americans had an appreciation for elegance and taste.

Rita Hayworth

Rita HayworthGreat actresses of today such as Meryl Streep, Judi Dench, Kate Winslet, Maggie Smith, and Emma Thompson know you don’t have to do the horizontal waltz to exude sex appeal.

They leave something to the imagination.

So why do otherwise intelligent women show up at the White House in flip-flops?

Why do “Walmart people” feel they can go shopping looking like two-legged rubbish bins?

Dare I offer my humble opinion? I fear there is very little child-rearing. Too many parents are abrogating that responsibility to schools, daycare centers, etc. The result is a nation in which millions of kids have little or no understanding of shared values, self-discipline, social responsibility, respect for others, or what we used to call “good manners.”

All of that is utterly passé. The idea for too many young girls today is to look trashy, show as much booty as they can and have a big ugly tattoo poking out above their butt crack.

When I was teaching at the University of Illinois, I couldn’t believe how many female students came to my 8 a.m. class in their pajamas. They couldn’t have cared less about how they appeared. But hey, at least they were comfortable.

I think attitudes began to change dramatically in the counterculture, hippie-fueled, “turn on, tune in, drop out” 1960s when the mantra was: “if it feels good, do it.”

Miss Manners was about as relevant back then as powdered wigs and hoop skirts.

Therefore, we can argue that it’s “generational.” OK, I agree, up to a point. Back in “the day” (and here I am dating myself), we wore tight jeans and white t-shirts with cigarette packs rolled up in the short sleeves. Some of us had “Ducktails,” and we liked to cruise around in customized cars equipped with thunderous glass pack mufflers.

But how many of us looked like those people at Walmart–or for that matter at McDonald’s, Taco Bell, Burger King, or I-Hop? Because I have seen them at those places also.

Until the 1960s people took a lot more pride in their appearance mainly because (in my case, at least) my mother would never have allowed me to walk out the door looking like a vagrant. I think too many parents today don’t provide that kind of supervision. Few teach their kids any discipline and instead infuse them with the idea that it’s not necessary to respect others, their property, or their opinions.

School teachers today tell me that when they get kids from homes like that (and that means most kids) every time they attempt to punish them the parents circle the wagons around their brats and often it’s the teacher who gets disciplined. I can’t imagine what it must be like to teach high school today.

That’s why there is such an excess of people who feel “entitled” to say and do anything they want. Think about the hordes of today’s barbarians who, like the Visa-goths and Huns who sacked Rome, are able to enter a Nieman-Marcus or Macy’s store with trash bags, strip shelves bare, and walk out with impunity.

Gang of thieves leaving Nieman-Marcus with loot

Gang of thieves leaving Nieman-Marcus with lootWhy is this happening? Why? Because we are allowing it to happen. Because Black Lives Matter leaders say openly that what those people are doing is “not looting, but reparations.” What a ludicrous rationalization.

“These stores owe the black community,” BLM kingpins say. That’s ethical vigilantism and victim distortion. They are encouraging response to a real or imagined injustice by urging remedial cheating, lying, and theft as “payback” for past indiscretions and biases. When someone belongs to a group that is commonly treated with bias or has a history of being so treated, or when an individual feels, perhaps legitimately, that he or she is personally discriminated against or disliked because of factors such as appearance, race, social background, or past indiscretions, they feel empowered to loot and steal. Some even go so far as to attack Asians or elderly pensioners on the street–all because of their perceived victimhood.

It’s a dangerous victim mindset that creates a crippling rationalization that says stealing from a Walmart or Walgreens is okay because those allegedly aggrieved are filled with irrational and groundless hostility. There is also the fact that punishment is just about nil for this kind of unlawful activity.

The result is that significant portions of our nation are sliding dangerously into anarchy. It’s as if those violent “Purge” films, in which citizens are given one full day to commit any kind of crime they want with impunity, are no longer Hollywood fiction, but reality.

Who knows where all of this will end. I am not optimistic given the feckless and irresponsible leadership we are seeing in our cities.

October 15, 2021

Humor yesterday and in today’s cancel culture world

The other day I watched Netflix’s “Closer” Special with comedian Dave Chappelle.

Now, don’t get me wrong. Chappelle is a funny guy. I especially respect him for his “anti-PC” comedy and commentary. It takes guts to speak your mind openly in today’s politically correct and cancel-culture world where just about everybody feels entitled to be perpetually offended.

Chappelle did not back down during his “Closer” show. He defended himself against the PC mob which has decided that certain topics (homosexuality, transgenderism, gender confusion, lesbianism, the LGBTQ+ community, ethnic and racial minorities, illegal migrants, and even the criminals who loot stores in broad daylight) are off-limits.

Apparently, the only human beings that aren’t off-limits are straight white males. They can be ridiculed and called everything from Nazis to white supremacists with absolute impunity by comedians, radical politicians, and media mavens. The hatred I hear directed at people like me (yes, I am a white male) by people like AOC, Rashida Tlaib, and other members of the bigoted anti-Semitic squad is not only condoned but seems never-ending.

But that’s a topic for another post. Let’s get back to Dave Chappelle.

As comedian and actor Damon Wayans said following Chappelle’s special: “I feel like Dave freed the slaves. Comedians were slaves to PC culture. As an artist, Chappelle is Van Gogh. He cut his ear off. He’s trying to tell us it’s OK.

Dave Chappelle: The Closer.

Dave Chappelle: The Closer. “I can’t speak about the content of (Dave’s) show, Wayans continued. “But, there’s a bigger conversation we need to have. Somebody needs to look us in the eye and go ‘You’re no longer free in this country. You’re not free to say what you want, you say what we want you to say. Otherwise, we will cancel you.’ That’s the discussion we need to have.”

Amen.

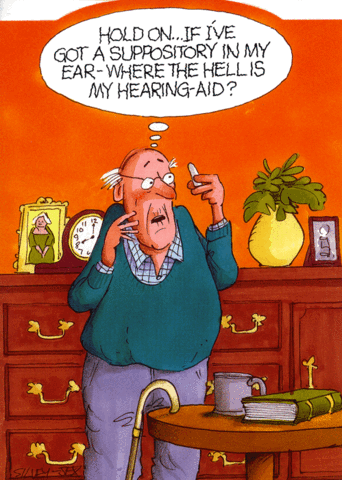

Having said all of that, I have to say I am not a fan of the vulgarity and gutter humor that seems to be the trademark of comedians today. I certainly haven’t seen all of Dave Chappelle’s performances, but the “Closer” show was permeated with enough F-bombs, bodily fluids, and other corporeal jokes to last me for a while.

People who are much smarter than me who analyze these sorts of things say comedians fill their routines with obscenities because they are holding a figurative mirror up to society. The fact is, we live in a vulgar world. Comedians have discovered they can get laughs going for the lowest common denominator and there are plenty of those in today’s audiences.

And that brings me to the real reason I am posting about this today.

I remember when comedy was very funny, even hilarious, without the crude humor. I remember when you could listen to or watch a vast array of comedians who could keep an audience laughing for an hour or more without uttering a single f-bomb or swear word.

They used wit, satire, wordplay, irony, farce, slapstick, parody, hyperbole, deadpan, anecdote, self-deprecation, ethnic, and good old observation to get laughs. And it worked!

I guess I’m dating myself here, but here is a list of some of those classic “clean” comedians. It came to me via e-mail, so in the interest of full disclosure, I didn’t compile it.

That note said that according to a UC Berkeley professor who studies humor in America, it’s a little-known fact that while Jews constitute only about 2 percent of the U.S. population, there was a time when they comprised about 50 percent of the famous comedians.

It went on to ask if you remembered some of the old “Borscht Belt” Catskill Comics of the 1940s and 1950s—many of whom got their starts doing stand-up comedy in that region of New York state.

Here’s a list of some of those classic comedians:

Shecky Greene, Red Buttons, Totie Fields, Joey Bishop, Milton Berle, Jan Murray, Danny Kaye, Henny Youngman, Buddy Hackett, Sid Caesar, Groucho Marx, Jackie Mason, Woody Allen, Lenny Bruce, George Burns, Allan Sherman, Jerry Lewis, Carl Reiner, Shelley Berman, Gene Wilder, George Jessel, Alan King, Mel Brooks, Phil Silvers, Jack Carter, Rodney Dangerfield, Don Rickles, Jack Benny, Mansel Rubenstein, and so many others.

[image error] Henny Youngman, king of the one-linersThere was not one single swear word in their comedy.

Take a look:

I just got back from a pleasure trip. I took my mother-in-law to the airport.Do you know what it means to come home at night to a woman who’ll give you a little love, a little affection, a little tenderness? It means you’re in the wrong house, that’s what it means.A man is hit by a car while crossing a street in Beverly Hills. A woman rushes to him and cradles his head in her lap, asking, “Are you comfortable?” The man answers, “I make a decent living.”I’ve been in love with the same woman for 49 years! If my wife ever finds out, she’ll kill me!What are three words a woman never wants to hear when she’s making love? “Honey, I’m home!”I once wanted to become an atheist, but I gave up – they have no holidays.Someone stole all my credit cards, but I won’t be reporting it. The thief spends less than my wife did.We always hold hands. If I let go, she shops.My wife and I went back to the hotel where we spent our wedding night. Only this time I stayed in the bathroom and cried.My wife and I went to a hotel where we got a waterbed. My wife called it the Dead Sea.She was at the beauty shop for two hours. That was only for the estimate. She got a mudpack and looked great for two days. Then the mud fell off.

Milton Berle interacting with the audience

Milton Berle interacting with the audience

And finally, this old chestnut that comes about as close to a “dirty” joke that you would have heard in the Borscht Belt.

Q: Why are Jewish men circumcised?A: Because Jewish women don’t like anything that isn’t 20% off.

October 14, 2021

Some Thoughts on the Art and Craft of Writing

I was interviewed recently about the art and craft of writing in general and writing in the historical fiction genre in particular.

As a journalist for some thirty years, I interviewed thousands of people all over the world. Now that I am on the other side of the table, I am finding that being the interviewee is as different from being the interviewer as chalk and cheese.

Don’t get me wrong. I enjoy being interviewed because it obliges me to think about what I do. It’s a lot like teaching. You must be able to verbalize your skills and knowledge and present them in a compelling way to teach effectively.

That’s not always easy to do. But I thought I would share my interview with my readers. I hope you will find it useful and perhaps even enjoyable.

Q. What historical time periods interest you the most and how have you immersed yourself in a particular time?

A. Growing up in rural Kansas I was always fascinated by the state’s 19th Century history. Kansas was a pivotal state before the Civil War because it entered the union as a free state and was populated–especially in the Northeast–by abolitionists. Kansas was a terminus for the Underground Railroad.

After the Civil War, it became about as wild and violent as any state in the union. Cattle drives from Texas, wild cow towns, outlaws, legendary lawmen and fraudsters of every stripe gave Kansas a wicked reputation. At the same time, the 19th Century in America was a time of fantastic growth, invention, progress, and expansion.

For some, such as Native Americans, this growth was not a pleasant experience, and in some cases, it was quite deadly. For others, the possibilities seemed limitless. Prosperity seemed restricted only by one’s determination and effort.

Q. Introduce us briefly to the main characters in Book 1 of the Finding Billy Battles trilogy.

A. William Fitzroy Raglan Battles is the main character in the trilogy. We meet Billy Battles through his great-grandson who meets him when he is 98 years old and living in an old soldiers’ home in Leavenworth, Kansas. The great-grandson inherits Billy’s journals and other belongings. Then, following his great-grandfather’s request, he produces three books that reveal Billy’s fantastic life.

The book begins with Billy introducing himself. We learn that his father is killed during the Civil War. He is reared by his widowed mother, Hannelore, a second-generation German-American woman who has to be both mother and father to her only son, rears him.

It is a tall order, but Billy grows up properly and is seemingly on the right path. His mother, a hardy and resilient woman, makes a decent living as a dressmaker in Lawrence, Kansas. An ardent believer in the value of a good education, she insists that Billy attend the newly minted University of Kansas in Lawrence. She is a powerful influence in his life, as are several other people he meets along the way.

There is Luther Longley, an African-American former army scout who Billy and his mother meet at Ft. Dodge in 1866. He escorts them the 300 miles to Lawrence and winds up being a close friend to both Billy and his mother.

There is Horace Hawes, publisher and Editor of the Lawrence Union newspaper who takes Billy with him to start a new paper in Dodge City. There is Ben Minot, a typesetter and former Northern Army Sharpshooter, who still carries a mini ball in his body from the war and a load of antipathy toward The Confederacy.

There is Signore Antonio DiFranco; the Italian political exile Billy meets in Dodge City. There is Mallie McNab, the girl Billy meets, falls in love with, marries and with whom he hopes to live out his life. There is Charley Higgins, Billy’s first cousin, who sometimes treads just south of the law, but who is also Billy’s most faithful compadre.

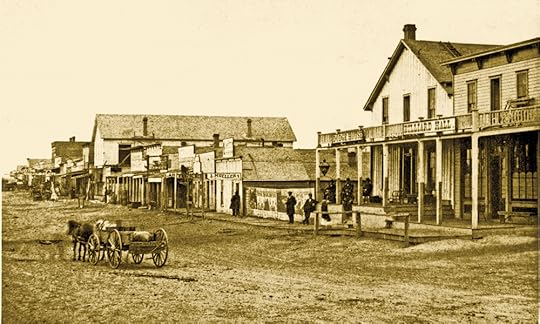

Dodge City, Ks ca. 1878

Dodge City, Ks ca. 1878Then there is the Bledsoe family–particularly Nate Bledsoe who blames Billy for the deaths of his mother and brother and who swears vengeance.

Book one of the trilogy ends with Billy on a steamship in 1894 heading for French Indo-China and other points in the Orient where one adventure (and misadventure) after another awaits him.

Book 2, The Improbable Journeys of Billy Battles, begins with Billy aboard the S.S. China headed for Saigon from San Francisco. Aboard the S.S. China Billy meets the mysterious Widow Katharina Schreiber, a woman who propels Billy into a series of calamities and dubious situations. She may or may not be a good influence on him.

He also meets a passel of shady characters as well as some old friends from his days in Kansas, etc. Events conspire to embroil him in a variety of disputes, conflicts and struggles in places like French Indochina and the Spanish-American War in The Philippines–events with which a Kansas sand cutter is hardly equipped to deal.

How does he handle these adventures in the “mysterious East?” You will have to read Book #2 to find out!

Q. What drew you to write this story