Esther Crain's Blog, page 19

June 3, 2024

The mystery of the “phantom phaeton” driving in Central Park and astonishing crowds in 1893

On a Saturday in late November 1893, The World ran an article about what headline writers dubbed the “phantom phaeton.”

In the late 19th century city, everyone would have known what a phaeton was—a horse-drawn carriage with short sides and oversize wheels. Wealthier New Yorkers tended to be the ones riding and driving this light, sporty vehicle.

But the phantom phaeton The World wrote about had no horses pulling it, and its driver went unidentified. “For the past week a mysterious, self-propelling carriage has astonished the afternoon throng in Central Park,” the article stated.

“It threads its way easily among the crush of equipages on the East Drive, turning, winding in and out, and checking or increasing speed as readily as any of the vehicles drawn by horses.”

After cruising through Central Park following a 3:30 p.m. stop in front of the Plaza Hotel, the phantom phaeton would then turn west and end up on Riverside Drive. “It moves noiselessly and without smoke, gliding along without any locomotive-like clankings or puffings,” wrote The World.

The phantom phaeton wasn’t New York City’s first automobile; in 1885 a manufacturer on West 53rd Street began making a type of motor car called the Allen, according to a 2006 New York Times article.

But it might have been one of the first privately owned vehicles to make regular appearances along the crowded drives of Central Park and Riverside Drive, where people were stunned by what The World called “a novelty” that could “cover a mile” in two minutes.

The World addressed the mystery: where did this “motor wagon” with rubber tires come from, and how does it work? A reporter tracked the phaeton to Jones’ Wood, a tract of land between Lenox Hill and the East River that was once considered as the ideal spot for Gotham’s first public park.

A specific owner was never identified, but the reporter wrote that it was “of a type said to be popular in Germany….The motor is driven by gas which is generated as needed by ordinary benzine, which is carried in a closed copper tank under the seat….The speed is regulated at will and the steering done by the valves before the seat.”

What the article doesn’t say is what we know now: the era of the automobile was beginning. Soon, “devil wagons” were all the rage. In 1899, the city held its first “automobile parade,” featuring electric and steam-powered cars. (Video below)

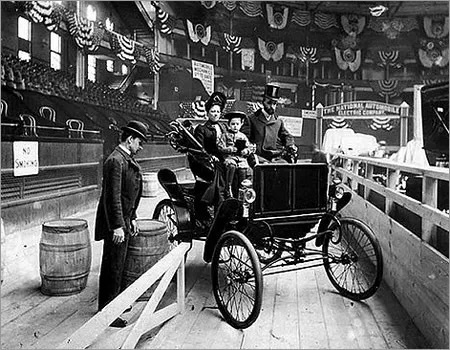

A year later, Madison Square Garden became the site of the first National Automobile Show (fourth image)—the same year New York State counted 500 registered privately owned cars, and “automobile stages” began ferrying passengers on Fifth Avenue (last image).

By 1910, cars were a regular part of the streetscape, and in 1920 the first traffic signal went up on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street. (A little too late for Henry Bliss, the first New Yorker to be killed by a car; in 1899 he was struck by an electric taxi at Central Park West and 74th Street.)

The World article ended by asking a coachman who worked at the West Side stable of John D. Crimmins what he thought of the phantom phaeton, which cruised past the stable on its daily trips across Manhattan.

The coachman said automobiles should be a success for country driving. “‘But for city use,’ he added, ‘no machine can take the place of a skilled hand on the box.'”

“But then, people scoffed at Robert Fulton when he began,” concluded The World.

[Top photo: driving past the Hotel Empire on Broadway and 62nd Street; MCNY, 1898, X2010.11.8213; second image: The World, 1893; third image: 1905, MCNY, X2010.34.1657; fourth image via Wired; fifth image (video): Library of Congress; sixth image: NYPL Digital Collections]

May 27, 2024

Solemn scenes from Decoration Day at Green-Wood Cemetery

When these photos from the collection of the Museum of the City of New York were taken at Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery at the end of May in 1899, Memorial Day didn’t exist.

“Decoration Day,” however, was an established holiday celebrated every May 30. The idea was to visit the final resting places of thousands of Civil War dead and “decorate” their graves with flowers while clearing away dirt and debris.

The people visiting Green-Wood in the images are here on Decoration Day. This cemetery with its rolling hillsides and towering view of New York Harbor opened in 1838, and 30 years later became the burial site of thousands of Civil War soldiers.

The black and white images of crowds dressed in black and white mourning clothes lends a sense of solemnity. In the top photo, the caption states that “a band leads a group of visitors near the gate.”

In the second image, the caption mentions a parade—apparently of the uniformed men on the right. The third image shows a marching band as well.

Are the people in the photos visiting dead loved ones who fought in the Civil War? The captions don’t tell us the details, but the date of their visit offers a clue.

[Images: MCNY; photo 1: 93.1.1.17241; photo 2: 93.1.1.17242; photo 3: 93.1.1.3133]

A vanished Henry Hudson memorial on Riverside Drive, and the sculpture that replaced it

It looked like an elegant streetlight: a slender pole of bronze standing on a granite base 18 feet high over a circular sitting area that’s part of Riverside Park.

Planted into a bed of flowers and shrubbery at 72nd Street and the beginning of Riverside Drive, the globe-topped monument consisted of inscriptions and bas reliefs inspired by Henry Hudson, whose namesake river ran just to the west.

You won’t find the monument there anymore; it’s long since been carted away.

So how did a memorial to Henry Hudson end up on Riverside Drive, opposite the Drive’s row house mansions and free-standing palaces, including the 75-room, Chateau-like Schwab Mansion (at right)—and why was this remnant of early 1900s Gotham removed?

The idea for the Hudson monument goes back to the turn of the century city. That’s when New York began planning the Hudson-Fulton celebration—a massive two-week event commemorating the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson’s exploration of the river that bears his name, as well as the 100th anniversary of Robert Fulton’s Clermont paddlewheel steamboat.

The celebration would run from September 25 to October 9, 1909. Festivities in the works were unlike anything the city had ever seen, at least since the Washington Centennial in 1889.

To honor these maritime pioneers, officials scheduled a (above) flotilla of naval ships (with replicas of the Clermont and Hudson’s Half-Moon), fireworks, two parades, signal fires from Governor’s Island to Spuyten Duyvil, and the nighttime lighting of bridges, statues, and city buildings with thousands of incandescent bulbs.

Amid the excitement of all these plans, the Colonial Dames of America decided to build the bronze monument to Hudson. It was unveiled on September 29, 1909, in then middle of the Hudson-Fulton Celebration, to a crowd of Americans and Dutch dignitaries.

“There was a great fanfare of trumpets, a little woman in a pongee suit pulled a cord and ran from under, the Stars and Stripes came down, the Dutch colors followed, and the tall bronze and granite shaft . . . stood revealed,” wrote the New-York Tribune.

For the next five decades, the Hudson Memorial remained on Riverside Drive. And it might be there today if it wasn’t “toppled by a truck in the 1950s” as NYC Parks put it.

Evidently it was too damaged to repair, or perhaps the popularity of the monument had run its course—especially in a city that honored Hudson with an eponymous river, a northern Manhattan bridge, and a parkway.

But there is a memorial at this circular spot once again: a sculpture of Eleanor Roosevelt. Dedicated in 1996, “this piece depicts Roosevelt in heroic scale half-seated against a boulder with her hand on her chin in contemplation,” notes NYC Parks.

Surrounded again by greenery, the circle is a gathering spot for strollers and loungers. Instead of the magnificent Schwab mansion, the memorial stands in the shadow of Schwab House, the red-brick co-op that replaced the chateau in 1950.

It’s a fitting tribute to a New York City-born First Lady, and like the sculpture of Joan of Arc 21 blocks north at Riverside Drive and 93rd Street, it’s one of the few statues in a city park that honors a woman who actually lived—not a mythological or fictional female.

Riverside Drive is lined with fascinating memorials from the early 1900s, from recognizable figures like Joan of Arc to dramatic monuments honoring fallen firefighters and Civil War veterans. Find out their backstories by signing up for Ephemeral New York’s Riverside Drive Mansions & Monuments walking tour. Sunday, June 16 still has openings—click here for more info!

[Top image: LOC, 1910; second image, 1912: MCNY, X2010.11.3083; third image, 1909: MCNY, F2011.33.560]

May 20, 2024

A ghost shoe store sign keeps Art Deco alive on bustling 34th Street

Some ghost signs are hard to decipher. They appear as leftover letters and logos hidden behind newer store signage, or as faded ads on the side of a building.

But the A.S. Beck sign screams to be noticed. The large gold letters appear at the top of an Art Deco-style windowless building, the name underscored by three dots.

Plus, it’s also the only old-school ghost sign on the crowded, grimy shopping strip of 34th Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues opposite Macy’s and with Penn Station around the corner.

So who was A.S. Beck, and what did he hawk here?

Alexander S. Beck was a Hungarian immigrant who first worked as a butcher after arriving in New York in 1888 before going into the retail shoe business, according to a 2015 article from Queens Chronicle. He opened his first shoe store in Greenpoint.

“By 1920 he had 13 stores and decided to sell his company to The Diamond Shoe Corp. for $1 million,” wrote the Chronicle of Beck, who lived in Canarsie. “In the agreement it was stipulated that the company would always retain his name.”

Besides his 34th Street location, Beck’s name graced 147 other stores across the country at the company’s peak in 1945, continues the Chronicle. (Above, on 34th Street in 1940)

“But the business’s fortunes turned and by 1972 the only three stores still operating in Queens closed,” states the article. “The final store, opposite Macy’s in Manhattan, closed in 1982.”

It’s been 42 years since the store shut its doors—but Beck’s name still looms large on 34th Street. It’s ignored by many but sparks curiosity in New Yorker like myself, who seek the stories behind vintage signs.

[Third image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

A carriage house with an upstairs artist studio is the last survivor of an East Side stable row

In the 1870s, East 63rd Street between Park and Lexington Avenues was taking shape as a residential block of brownstones designed for upper middle class families.

Thirty years later, the out-of-style brownstones were destined for the wrecking ball.

This quiet stretch of East 63rd Street was transitioning into a “stable row”—a side street in a posh neighborhood where the new wealthy mansion dwellers residing on Fifth and Madison Avenues would build private stables to house their horses and luxury carriages.

C. Ledyard Blair, a young banker and lawyer whose vast fortune came in part from his railroad tycoon grandfather, decided to build a stable here too.

At the time, Blair, his wife Florence, and their four daughters lived at 15 East 60th Street. The Blairs were in the process of constructing a massive estate in Somerset County, New Jersey (dubbed “Blairsden”), where Ledyard and Florence—both accomplished equestrians who belonged to the city’s Coaching Club—could ride, entertain, and enjoy private family time.

In the next decade, the Blairs would relocate to a new mansion at Two East 70th Street. But for now, East 63rd Street was a close-to-home space for their horses and vehicles.

In 1899, Blair purchased two lots where a pair of brownstones once stood, per the Landmarks Preservation Commission. He then brought in the architectural firm Trowbridge and Livingston to come up with a new building that would be imaginative yet dignified.

The result is this four-story bit of enchantment at 123 East 63rd Street. Completed in 1900 (second photo), the stable looks like a Beaux-Arts dollhouse. The limestone and red brick facade is topped by a slate mansard roof with ocular windows; the third floor has a rounded arch over the center window, decorated with a delightful iron balcony.

Stables like this one often ended up as artist studios once the carriage era was over. But this stable was intended to be an artist studio from the beginning.

Blair gave the upper floors to his friend, John White Alexander—a portrait artist and mural painter who was a contemporary of William Merritt Chase and John Singer Sargent, notes the Somerset Hills Historical Society.

Alexander’s oil painting of Florence Blair, painted in 1901 (below), was most likely painted in the East 63rd Street stable-slash-studio, per the Society.

It’s not clear when Alexander and Blair left the stable. But by about 1920, this one and the many others across Manhattan had outlived their purposes.

Automobiles now ruled Manhattan’s roads, and parking a car required a lot less space (and fewer hired hands) than maintaining a carriage.

How this lovely relic managed to survive while neighboring stables met the wrecking ball isn’t clear. It may have to do with the stable’s transformation into a private club in 1953, per the LPC.

Today, 123 East 63rd Street is owned by the Gurdjieff Foundation. Wedged between tall apartment buildings, the stable and artist studio is still enchanting and startlingly beautiful.

Consider it a remnant of an Upper East Side when fanciful stable rows with whimsical design motifs interrupted unbroken lines of more restrained townhouses and mansions.

East 66th Street was another Stable Row, as was East 69th Street. This gingerbread house of a stable still exists on East 38th Street.

[Second photo: Architectural Record, 1901; fifth photo: Wikipedia; sixth image: Find a Grave]

May 13, 2024

The holdout stable squeezed between white brick apartment houses on the Upper East Side

What kind of block was East 63rd Street between Second and Third Avenues in the first half of the 20th century?

Like so many other streets hemmed in by elevated trains and relatively close to the riverfront, it was a modest stretch of walk-up residences, stores, and stables—anchored on the Second Avenue end by the Clara de Hirsch Home for Working Girls, one of the city’s young women’s residences that offered room, board, and a sense of security for modest fees.

By the 1960s, however, this part of East 63rd Street had undergone a facelift.

Gone were most of the low-rise buildings, overtaken by a tide of almost identical tall postwar apartment houses. Their white glazed brick “was supposed to make them look like beacons of clean, shiny modernism in the midst of the dirty city,” wrote The New York Times in a 2011 article.

Nothing illustrates the changed face of the block like this lone holdout stable at 212 East 63rd Street, now hemmed in by white-brick giants.

Even the sides of the stable, which juts out from its neighbors, is covered in white brick. It’s a strange attempt to obscure its old-school style and construction.

How this stable managed to evade demolition is a mystery. Built in 1899 and once home to horses and the grooms who tended to them, it has the architectural hallmarks of the late Gilded Age: rounded, Romanesque ground-floor windows and doorway, and the ornamental arrangement of the bricks above them.

Tidy and well maintained, the stable’s backstory is missing (as is its chimney, though maybe it’s just out of view). It has long since transitioned into a residence.

This holdout serves as a reminder of an East 63rd Street with rougher edges, and while other buildings fell, it continues to grace the contemporary cityscape with its modest beauty and 19th century vibes.

[Third image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

What a 1960s road map reveals about New York’s hospitals and department stores—then and now

Around 1964, Hagstrom published a road map of New York City—the old-fashioned folding kind that always ended up in a creased mess. And it reveals some interesting changes in the cityscape over the past 60 years.

Back then, subway routes were noted as either the IRT, BMT, or Independent line; the Metropolitan Opera House stood at Broadway and 39th Street; and the neighborhood about to be rechristened the East Village was a vast and empty space simply labeled “East Side.”

But the “High Spots in New York” map, as Hagstrom called it, reveals even more differences between the city of the 1960s and contemporary Gotham in the map’s sidebars, which list places of interest worth visiting.

Skyscrapers worth a look include the Singer Tower, born in 1908 and demolished in 1968. Nightlife suggestions feature the Village Gate and Sammy’s Bowery Follies, both vanished. Movie theater options include the Greenwich, formerly on Greenwich Avenue and 12th Street (now a gym), and the Gramercy, once on Lexington Avenue and 23rd Street.

But I think the biggest changes are in two lists the map provides: one of hospitals, the other of department stores.

The New York of today is a city with a handful of huge hyphenated hospital conglomerates. But look at the hospitals from 1964.

St. Luke’s and Roosevelt are separate entities, St. Vincent’s serves the Village, University hasn’t been renamed NYU Langone, and Sydenham, which opened in 1892 on East 116th Street, operated in West Harlem. (It closed in 1980.)

The department store list is a little heartbreaking for New Yorkers who remember the city as a department store wonderland. Of the 21 stores on this list, I count only four that still stand: Macy’s, Saks, Bergdorf’s, and Bloomingdale’s.

It’s not that the city was better off with more small hospitals or a larger selection of department stores. But it’s jarring to see the differences between 1960s New York and the Manhattan we live in today laid out so starkly on a 60-year-old road map.

May 6, 2024

What’s on the menu for Mother’s Day 1960 at the Park Lane Hotel

It’s Mother’s Day 1960, and you’re part of a well-to-do family looking to celebrate the holiday at one of the Mother’s Day brunches hosted by hotels and restaurants all over the city.

You choose the Park Lane Hotel, which in 1960 actually was on Park Avenue, opposite the Waldorf-Astoria. (Since 1971, the Park Lane Hotel has been on Central Park South.)

So what’s on the menu? Things start off light, with the requisite offerings of consommé, grapefruit, and melon.

For the entreé course, the eggs benedict look tasty, but the boneless squab chicken casserole less so. And what exactly is “mother’s style” chicken fricassee?

Maybe the simplicity of the cold buffet selections are the way to go, topped off with the mysterious (but probably delicious) “mother’s day” layer cake.

I’m sure the actual Mother’s Day brunch at the Park Lane in 1960 satisfied many families and the moms who were honored.

But the menu reveals something interesting about how restaurant menus have changed in the last 60 years. Rather than a selection of the kind of adventurous offerings contemporary New York City menus typically feature, this one reflects a very midcentury American palate for casseroles, strawberry shortcake, creamed chicken, and V-8.

Did New York restaurants evolve at some point in the last 60 years, or did they typically offer the kinds of unfancy food options people actually prepared and ate in their own homes at the time?

Then again, the price of this meal for each person is a mere $5, per the menu. Even for 1960s prices, that sounds like a decent meal in an upscale setting for a bargain.

From a merchant’s mansion to a home for friendless women, the many lives of an 1847 brownstone on 14th Street

A rollicking mix of apartment buildings, loft spaces, bars, and discount stores, West 14th Street hasn’t been considered an elite place to build a home for almost two centuries.

But in the New York of the 1840s, what had once been the dividing line between the urban city and the wilds of Manhattan was transforming into a fashionable residential thoroughfare.

Families with money and means began purchasing land on West 14th Street and putting up wide, roomy brownstones from Union Square to Eighth Avenue. One of those new brownstone dwellers was Andrew S. Norwood.

Norwood’s name wouldn’t resonate with contemporary city residents. But in his day, this Knickerbocker New Yorker was considered one of Gotham’s “solid and substantial” citizens, per Valentine’s Manual of Old New York.

Born in 1770 and the son of a Patriot, Norwood became a successful merchant, stockbroker, the owner of a line of packet ships, a founder of the Presbyterian church on Cedar Street, a friend of the Marquis of Lafayette and “the Washington family,” and a resident of a posh home on Bond Street, per Valentine’s Manual.

In 1845, he added real estate developer to the mix and bought several lots on 14th and 15th Streets between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, states the Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC). By 1847, he had built the first three brick or masonry buildings on the north side of the block: numbers 239, 241, and 243 West 14th Street.

All three met the definition of “first class” single-family houses, per the LPC. Norwood chose 241 as his family home, an outstanding example of “a transitional style which combines Greek Revival with Italianate features,” wrote the LPC, noting the full-length French doors on the first floor windows, the cast-iron balconies, and the brownstone trim on the red brick facade.

We can assume Norwood and his family lived well inside their new house, with its 14-foot ceilings, 13 fireplaces, mahogany parlor doors, silver doorknobs, and mantelpiece made of Carrara marble. The generously sized house had room for dinner parties and servants’ quarters, and one can imagine the family hosting prominent West 14th Street neighbors, like the Van Beurens.

At age 86, Norwood passed away in his house in 1856—just as commercial establishments were coming to 14th Street and the residential vibe was giving way to stores and theaters.

The house stayed in the Norwood family until the turn of the century. Norwood’s son, also named Andrew and also a stockbroker (and original member of the New York Stock Exchange), became the owner, per the LPC.

Whether he lived there until his death in 1879 isn’t clear; an 1871 ad in the New York Daily Herald notes an upcoming auction of “elegant household furniture” at 241 West 14th Street.

In any case, the house’s days as a 19th century private residence were over. By the 1880s it served as a boarding house, according to a New York Times mention.

In 1890, the house changed hands again. Now it functioned as the headquarters of the New York Deaconess’ Home and Training School of the Methodist Episcopal Church, an organization that “trained nurse deaconesses who care for the sick poor in their homes,” according to an 1895 New York City charities directory.

King’s Handbook of 1892 added that the charity had “about a score of inmates” who study the bible, medicine, hygiene, and nursing to prepare for being in service to “the poor and the sick…the sick and the dying.”

Five years later, a different type of “inmate” lived in Andrew Norwood’s house, which had now become the “Shelter for Respectable Girls.” Run by a Christian denomination, the shelter put out an urgent plea in the New York Times in 1899 for donations to continue its work “giving shelter and help to respectable girls who are homeless and friendless.”

In 1900, more than 500 girls stayed at the shelter, which catered to young “friendless” women who came to New York for job opportunities yet had no connections, nor a “respectable” place to stay.

In the early 1900s, after the Norwood estate sold the house, a dentist became the occupant. At some point in the 20th century it transformed into a funeral home. Perhaps this is what the vertical sign hanging off the facade states in the fourth photo, above, from 1940.

Andrew Norwood’s home became a private residence once again in 1976, when a real estate broker named Raf Borello bought the property, according to venuereport.com. Borello began a 30-year restoration of this 1840s anachronism.

The restoration involved “uncovering layers of paint, plaster, dirt, and muck to bring the house back to its glory days,” stated venuereport.com. “By the time Borello died in 2005, the property was fully restored, featured a phenomenal garden in the back, and the exterior had been registered to the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission.”

What would come next for this revitalized remnant of pre-Civil War New York City?

It was purchased in 2007 and transformed into the Norwood Club, a members-only club described in venuereport.com by the owner, Alan Linn, as “a modern-day salon for the creative community in New York, a space to congregate, socialize and swap ideas. It is a ‘home for the curious.'”

The Club seemed to thrive for at least a decade, with more than a thousand members who submitted to an interview before being selected to join. Perhaps the pandemic took its toll, as the Norwood Club closed in 2022.

Since then, Andrew Norwood’s elegant brownstone, so lovely and stylish in its era, has been looking rough around the edges. Debris is scattered on the stoop, and the columns flanking the front doors are flaking and cracking.

Let’s hope a savior appears for this dowager of a brownstone on an unbeautiful block but with such a deep and rich backstory.

[Fourth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; fifth image: New York Times]

April 28, 2024

What remains of an East Harlem five and dime store that opened almost a century ago

It doesn’t look like much, just another semi-vacant commercial building—this one on the southeast corner of 106th Street and Third Avenue—now occupied by a Duane Reade.

But give it a closer look, and Art Deco decorative touches come in to view, like the patterns in the light bricks and small geometric shapes above the first and second floors. With its enormous windows, this space was meant to be welcoming and accessible.

On the 106th Street side is a slab in the middle of the facade by the roofline. It proudly carries a name: Kress. What was Kress?

Similar to Woolworth’s, S. W. Kress & Co was a five and dime retail chain that at its height had more than 250 stores across the country. Houseware, toys, accessories, candy, goldfish, underwear, notions, paper goods, and all kinds of random thingamajigs could be found in a Kress store.

The chain was founded by Samuel W. Kress in 1896 in Memphis. As stores expanded nationwide, Kress moved his company headquarters to New York City. He also purchased a Fifth Avenue penthouse for his family and his growing art collection.

Several Kress outlets soon opened in Gotham, including one on Fifth Avenue and 39th Street (shuttered in the late 1970s) and another at 256 West 125th Street. Opened in 1920, it was likely the very first New York City Kress store, according to Walter Grutchfield.

The Kress on East 106th Street made its debut five years later, stated Grutchfield, adding that it closed up in 1994. “It seems to have been the last surviving Kress store in New York,” he wrote.

Five and dimes were very popular in their 20th century heyday; they were utilitarian versions of more glamorous department stores that sold a variety of usually more expensive items under one roof.

Imagine this enormous Kress store in its 20th century prime, when the neighborhood was a shopping corridor bustling with middle- and working-class customers. The store would have been partly obscured by the Third Avenue Elevated tracks until the 1950s. (Above, in 1940)

Perhaps it’s fitting that Duane Reade now operates in the former Kress space. The pharmacy chain might be the closest replacement New Yorkers have for five and dimes like Kress and Woolworth—which had a store not too far away on Third Avenue and 121st Street.

[Third photo: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]