Esther Crain's Blog, page 18

June 24, 2024

The restored vintage terra cotta subway signs that greet you at Coney Island

Coney Island’s arching Stillwell Terminal, on Surf and Stillwell Avenues minutes from the boardwalk, makes for an impressive subway station.

Originally opened in 1919 and renovated in the early 2000s, this partly solar-powered structure is the largest above-ground station in New York City and the biggest rapid-transit station in the world, per the MTA. Thousands of beach-goers walk through its steel truss design to arrive and depart via four different train lines.

But what catches my eye is the old-school tiling and signage above the entrance, which looks like it dates back to the station’s early days more than a century ago.

On a green terra cotta plate in white and (very faded) red letters are BMT—for the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation, which ran several train lines terminating here until selling them to the city in 1940.

Surrounding the plates are subway tiles, a row of which are decorated like clovers with a few rosette designs higher up. Two additional green plates read “BMT Lines.”

Are all of these vintage-looking signs original? I can’t confirm, though an MTA press release from 2014 mentions the “distinctive green, white and red BMT Lines sign,” and that the new construction “also included a new portal building with the restored BMT terra cotta façade.”

Coney Island is rich with iconic old signs, from Nathan’s with the neon hotdog to the thrilling pink capital letters of the Wonder Wheel. What a treat to see that this fabled seaside destination still has the subway signage harkening back to its early 20th century heyday.

[Third image: David Shankbone/Wikipedia]

One July day, a painter captured a colorful glimpse of the beach and bathers at Far Rockaway

On July 13, 1902, painter Robert Henri took a day trip to Far Rockaway. Unlike more raucous Coney Island, this easternmost stretch of the Rockaway Peninsula had become a popular seaside destination for New Yorkers seeking peaceful relief from sweltering urban heat.

After sketching a scene of visitors streaming from a bathing pavilion to the beach, Henri “described his idea for the final oil in his diary: ‘blue sky. sun yellow pavilion…tel[ephone] pole brilliant colors of people on beach, walk and in pavilion. blue strip of sea,'” states the 1994 book, American Impressionism and Realism, per Sothebys.com.

The above painting is the final oil, simply titled “At Far Rockaway.” Henri at the time was moving away from Impressionism to a more realist style. But this rich landscape has an Impressionist feel—the pops of color from the parasols, hats, and willowy bathing dresses as well as the contrast of blue hues in the sky and ocean.

The visitors are mostly female; the contours of the sand appear like a soft embrace. American flags, perhaps leftover from the Fourth of July, wave in the breeze before a placid “blue strip of sea,” as Henri put it.

“Painted four years after the Rockaways were officially absorbed into the City of Greater New York, “At Far Rockaway” depicts the elevated boardwalk, a main attraction in the area, or one of a number of popular bathing pavilions offering comfort and shade to beachgoers,” stated Sotheby’s, which dolf what the auction house called a “celebration of modern seaside leisure.”

June 17, 2024

The Art Deco magic of Bloomingdale’s Lexington Avneue store sign

Like many of Manhattan’s legendary department stores, Bloomingdale’s developed in stages.

First came Lyman and Joseph Bloomingdale’s “Ladies’ Notions Shop” on Chambers Street, where they sold the trendiest garment of the 1860s: the hoop skirt.

In 1886, the Bloomingdale Brothers moved their store, renamed the “East Side Emporium,” to the hinterlands of Manhattan at Lexington Avenue and 59th Street.

“The store expanded steadily and by the 1920’s, Bloomingdale’s converted an entire city block,” states Bloomingdale’s website.

The block-long store that was put together piecemeal underwent an Art Deco makeover in 1930. A movie-marquee awning, metal decals along the facade, and geometric shapes above the main entrance decorate the store’s Lexington Avenue side.

What captures my eye is the Art Deco-style lettering on Bloomingdale’s facade and the entrance awning. I’m not enough of a typeface expert to know if it has a name.

But the san serif, all-caps lettering is a unique reminder of the magic of Art Deco—and that this beloved midcentury design style dominating many of Manhattan’s skyscraper districts can be found hidden away in unusual places: subway entrances, nameplates on building doors, and the lettering above store entrances.

[Third image: Wikipedia]

This opulent Fifth Avenue townhouse built in 1901 was home to the “world’s richest boy”

In 1901, a five-story, brick and limestone Beaux-Arts townhouse (below, far left) made its debut on Fifth Avenue between 79th and 80th Streets.

Described by one newspaper as “one of the finest houses on Upper Fifth Avenue,” this stylish piece of real estate wasn’t the most ostentatious mansion in the neighborhood.

But with its bow front, numerous ornamental carvings, and iron balcony wrapping around the fifth floor, it had an excess of Gilded Age architectural bells and whistles compared to its more restrained and balanced neighbors.

The owner, William Bateman Leeds, was a tremendously wealthy businessman. Born in Indiana, Leeds didn’t come from money. But this enterprising former railroad engineer founded a company that produced tin. After monopolizing the tin industry and eventually selling his company to U.S. Steel, Leeds earned the nickname the “Tin Plate King.”

At the turn of the 20th century, the Tin Plate King reportedly paid his first wife a million dollars for a divorce. After his marriage was dissolved he wed his second wife, Nonnie May “Nancy” Stewart, in 1901.

The Fifth Avenue house, which he bought for $260,000 and paid another $70,000 to add a marble hall and staircase, was a gift for his beloved bride.

The couple’s incredible wealth made them regulars on the society pages of New York newspapers. But it was their baby son, William Bateman Leeds, Jr., who arguably became the mansion’s most famous resident.

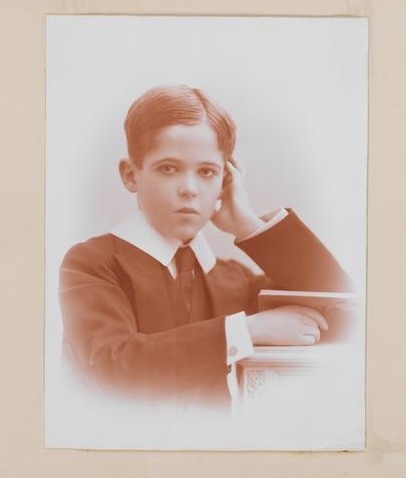

Dubbed the “world’s richest boy,” young William Leeds was born on September 19, 1902. From his earliest years, he had everything a pampered Gilded Age child could want—lots of toys, play clothes, and an entire playroom in his Fifth Avenue mansion, as these photos show.

But hobby horses and toy trains only go so far. “William’s life, sadly, was not all presents and playing,” wrote Susannah Broyles in a 2014 blog post from the Museum of the City of New York, which has these photos of young William in its collection.

“For some reason, his mother, Nancy, believed her son to be frailer than most and kept him secluded from the outside world for much of his childhood.”

Things drastically changed for the boy in 1908, when his father died at the Hotel Ritz while vacationing in Paris. Though accounts of the amount of money he supposedly inherited varies, William “was now the the proud inheritor of a cool $30,000,000 to $40,000,000 (nearly a billion dollars in today’s money),” states Broyles.

After selling the Fifth Avenue townhouse in 1911, William’s mother moved him to an estate in Montclair, New Jersey. While she relocated to London with the aim of remarrying into royalty, William was left behind “with a governess, housekeeper, and 15 servants to meet his slightest wish,” according to one 1912 newspaper article.

“Mrs. Leeds keeps in touch with the lad almost daily through cable messages and is kept constantly posted as to his physical condition and progress in school,” the article continued.

William joined his mother in England a year later, and she enrolled him at Eton. Nancy, meanwhile, found a Greek prince to marry in 1920 and became known for the rest of her life as Princess Anastasia (above painting, 1922)

By now, William was a young man, and his whereabouts regularly made the gossip pages. While visiting his mother in Greece he fell in love with 17-year-old Princess Xenia, and the two married in 1921 (below).

They eventually divorced, and William tied the knot a second time with a former Atlantic City telephone operator. The two maintained an apartment at 30 Beekman Place and shared a love of travel and yachting.

The world’s richest boy, who spent the first years of his life swaddled in luxury in a Fifth Avenue townhouse, didn’t turn out to be a stereotypical caddish rich kid or win-at-all-costs titan of industry.

As an adult, William kept a low profile and pursued philanthropy, “sending a boatload of medical supplies to Pitcairn Island in the dark days before Pearl Harbor, supporting a leper colony in Tahiti, donating an entire ambulance corps to the British when they were fighting Germany virtually alone,” per his obituary, among other causes.

After a cancer diagnosis, he died in 1972 at age 69 at his home in the Virgin Islands, an apparent suicide.

And what was the fate of his Fifth Avenue childhood home? After changing hands for several decades and being carved up into apartments, the townhouse was sold to a developer in 1959. A decade later, a 25-story glass and brick apartment tower took its place (above photo, middle building) and still stands today.

[Top photo: MCNY, 89.3.2.3; second photo: MCNY, 89.3.1.49; third photo: MCNY, 89.3.2.17; fourth image: MCNY, 89.3.1.41; fifth image: Wikipedia; sixth image: Wikipedia]

June 12, 2024

Explore the Gilded Age past of Riverside Drive on a breezy walking tour with Ephemeral New York!

Which 1903 mansion still features a faded sculpture of the owner’s six beloved children above the entrance? Who was the beautiful stage and screen star whose famous paramour bought her a townhouse on one of Riverside’s private carriage drives? Where was the chateau of a steel magnate who lost his fortune and tried to give his spectacular 85-room home to the city?

Why are there no brownstones on Riverside Drive, and no stores, either? How did a Medieval French heroine end up memorialized in bronze overlooking the Hudson River? Where is the row of townhouses so lovely that one writer dubbed them the “seven beauties”? Which solemn memorial has its origins in a deadly fire?

Discover the answers to these questions and a whole lot more by joining a relaxed and breezy tour of Riverside Drive with Ephemeral New York! No other avenue in Manhattan combines such stunning beauty and deep history quite like this quiet yet breathtaking avenue—which opened in 1880 and by the early 20th century became the city’s new millionaire mile.

Ephemeral New York leads regular walking tours exploring the Gilded Age past of Riverside Drive, and some spots on upcoming tours still remain:

Sunday, June 16 at 1-3:15 pm. Get tickets at this link

Sunday, July 7 at 1-3:30 pm. Get tickets at this link

Sunday July 28 at 1-3:30 p.m. Get tickets at this link

The tours are casual and refreshing—an enjoyable way to explore a piece of New York City while scoring some outdoors time during the loveliest season of the year. I hope to see lots of Ephemeral New York readers on these upcoming tours!

[Top photo: New-York Historical Society; second and third images: Library of Congress]

June 10, 2024

What Washington Square looked like when it was a military parade ground

Washington Square has been many things throughout New York City history.

In the 17th century, it was a marshy hunting ground, according to NYC Parks; two centuries later, it served as a potters field, execution site, and then a neighborhood park bordering an elite residential enclave.

The 20th century brought artists, protestors, NYU students, and park-goers enjoying the car-free ambiance.

But in 1826, Washington Square was rebranded as the Washington Military Parade Ground, a place where military exercises were conducted with soldiers in uniform.

Though the Square became an official public park in 1827, military regiments still gathered there—as this lithograph from 1851 reveals.

Click it to enlarge and take a look at this rich scene. It was painted by Otto Boetticher, a German immigrant turned New Yorker who enlisted to fight for the Union in 1861 and spent time in a Confederate prison camp.

But a decade before that, he captured the city’s Seventh Regiment “on review,” along with what look like well-to-do civilians in the park, the low-rise houses of University Place and West Fourth Street in the distance.

“In the background are two Gothic Revival–style edifices, New York University’s main building (also known as the University Building), to the left, and the Reformed Dutch Church, toward the center; both were demolished in the early 1890s,” states Metmuseum.org, which has this lithograph in its collection.

A portion of that circa-1835 university building actually exists—a spire is on display just south of the square near Bobst Library.

[Image: metmuseum.org]

The shell of a 1911 movie palace still stands on this Harlem block

In the 1910s, as motion picture mania swept the country, architect Thomas Lamb began carving out a niche for himself as one of the foremost designers of movie palaces.

In the early 1900s, audiences of this exciting form of entertainment would watch short reels and early features in storefront theaters and nickelodeons—which were typically small, no-frills places.

By 1910, movie palaces made their debut. These were enormous venues with lavish ornamentation and comfortable seating for large audiences that wanted to see the new screen stars in a safe, family-friendly setting.

One of Lamb’s first movie palaces stands on West 145th Street. Opened in 1911, the four-story Odeon (above) launched as a Vaudeville theater with a mix of live acts and motion pictures. It converted to a full-time movie palace by 1925, according to Cinema Treasures.

White terra-cotta and Romanesque arches are hallmarks of Lamb’s movie palace facades, and both features decorate the Odeon, which stands out like a cinematic fortress over the tenements that surrounded it (above photo, 1940).

Lamb went on to design at least 48 theaters in New York City, according to Christopher Gray in the New York Times in 2008, including the Rialto, Strand, and Rivioli—all in Times Square and all since demolished.

What played at the Odeon over the decades, as the neighborhood changed from a diverse one early in the century to majority African American by the 1920s?

Based on old newspaper ads, the fare seems to be the same Hollywood flicks as other theaters likely showed, with stars like Wallace Beery in 1930’s The Big House.

Clark Gable and Greta Garbo’s 1931 film Susan Lenox also played there. Note the top of the ad, which would have appealed to tenement dwellers in pre-air conditioned Manhattan: “always cool and comfortable.”

The movie palace era came to a close in postwar New York City. But the Odeon still stands because another use was found for the space.

In the 1950s, what was born a cathedral of cinema transitioned into the home of St. Paul’s Community Church, which occupies the movie palace to this day, according to David Dunlap’s From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan’s Houses of Worship. Congregants now enter the two Gothic-style doors were moviegoers once waited on line for their tickets.

Meanwhile, a “ghostly palimpsest,” as Dunlap calls it (see above photos), on both sides of the former palace still advertise the Odeon—which no longer officially exists in the streetscape but remains in the imagination.

Thanks to Justine for spotting this treasure!

[Second image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; third image: New York Age, 1933]

June 3, 2024

A left-behind ghost sign in East Harlem for New York City’s home-grown fried chicken chain

New York used to have its own restaurant chains rarely seen beyond city borders. Remember Tad’s Steaks? Chock Full o’ Nuts? Schrafft’s?

All have bitten the dust. (Though Tad’s might still be serving up their signature steaks and baked potatoes in its remaining Theater District outlet.)

But one Gotham chain, Kennedy Fried Chicken, is still going strong, mainly in the outer boroughs. This enduring and strangely endearing rip-off of Kentucky Fried Chicken launched in 1979.

That’s according to employees who spoke to a New York Times reporter in 2004 for a very interesting profile of the company. Wikipedia, however, has the launch date of the first store (in Flatbush) in 1969.

I don’t know when Kennedy Fried Chicken operated a restaurant on this East Harlem corner at First Avenue and 108th Street. Nor do I know when it shut its doors and a deli/convenience store moved in.

The Kennedy signs are showing wear and tear and have kind of a 1980s look. The deli has put up its own signage, leaving the Kennedy signs still up but easily overlooked.

Why the name Kennedy? Apparently the company founder had a fondness for President John F. Kennedy, according to another New York Times story from 2011.

A left-behind store sign in East Harlem for New York City’s home-grown fried chicken chain

New York used to have its own restaurant chains rarely seen beyond city borders. Remember Tad’s Steaks? Chock Full o’ Nuts? Schrafft’s?

All have bitten the dust. (Though Tad’s might still be serving up their signature steaks and baked potatoes in its remaining Theater District outlet.)

But one Gotham chain, Kennedy Fried Chicken, is still going strong, mainly in the outer boroughs. This enduring and strangely endearing rip-off of Kentucky Fried Chicken launched in 1979.

That’s according to employees who spoke to a New York Times reporter in 2004 for a very interesting profile of the company. Wikipedia, however, has the launch date of the first store (in Flatbush) in 1969.

I don’t know when Kennedy Fried Chicken operated a restaurant on this East Harlem corner at First Avenue and 108th Street. Nor do I know when it shut its doors and a deli/convenience store moved in.

The Kennedy signs are showing wear and tear and have kind of a 1980s look. The deli has put up its own signage, leaving the Kennedy signs still up but easily overlooked.

Why the name Kennedy? Apparently the company founder had a fondness for President John F. Kennedy, according to another New York Times story from 2011.

A building is demolished in Brooklyn, and a vintage faded bank ad comes back into view

It’s hard to estimate when this pristine green and white ad for Dime Savings Bank made its debut on the side of a tenement at Fourth Avenue and St. Marks Place.

Perhaps it was painted in the 1930s, when this Brooklyn thrift bank that got its start on Montague Street in 1859 “began an ambitious program of expansion,” states Suzanne Spellen in a 2010 Brownstoner post.

That expansion included operating bank branches across the borough and renovating its flagship bank building, a Classical-style beauty from 1908 on DeKalb Avenue at today’s Albee Square. (Below, in 1912)

Or maybe the ad dates to the post-war era, when the tenement facade was visible from afar and before someone decided to put up an oddly shaped 3-story wood and cinderblock building at 81-85 Fourth Avenue, which obscured the ad for decades.

Recently Number 81-85 met the demolition ball (below), and the Dime Savings Bank ad came back into view.

It’s a remnant of an era when people banked at local institutions that focused on everyday financial needs, such as savings accounts and mortgages. Originally, customers could open an account with just a dime—hence the name.

Dime no longer exists, a casualty of a changing financial landscape and a merger with Washington Mutual in 2002, per Atlas Obscura.

But the stunning flagship building on DeKalb still stands—a Landmarks Preservation Commission-designated historic architectural treasure now fronting 21st century Brooklyn’s first supertall apartment tower.

[First and third photos: Ephemeral reader ForceTube Avenue; second image: eBay.]