Esther Crain's Blog, page 15

September 16, 2024

When did the far East Village become known as Alphabet City?

New Yorkers have strong opinions about neighborhood names. Soho, Nolita, Tribeca—the names of these downtown enclaves probably sounded funny, even ridiculous, to longtime residents. But 30, 40, even 60 years on, they’re accepted in today’s Manhattan.

Yet if you describe any of the lettered streets in the East Village as part of “Alphabet City,” you might be met by an eye roll or outright contempt. The mockery and hostility toward Alphabet City endures even though the name has been around since the early 1980s.

One of the first mentions comes from a 1984 New York Times article in which the writer described the neighborhoods young people were choosing to colonize: “They are moving downtown to an area variously referred to as ‘Alphabetland,’ ‘Alphabetville,’ or ‘Alphabet City’ (Avenues A, B, C and so forth on the Lower East Side of Manhattan).”

An even earlier reference appears in a New York Daily News article from 1980, “Gentrification Comes to the Lower East Side,” describing a surge in young adults living beyond First Avenue.

“Avenue A is still the DMZ,” one interviewee tells the reporter. “While the one side has been the East Village since the days of hippie heaven, the other side has been known, by , and by hand-rubbing realtors, as Alphabet City.” (Loisaida, if you didn’t know, is a Spanglish corruption of “Lower East Side.”)

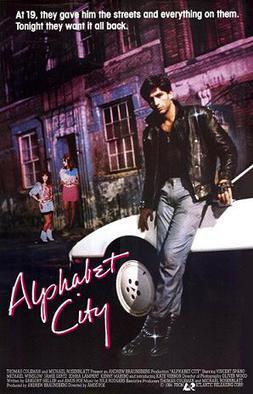

And depending on your generation, you may remember a 1984 movie titled “Alphabet City.” Directed by Amos Poe and starring Vincent Spano, this stylish crime drama focused on Italian American gangs and the drug racket. (Poster below left)

The geographic area that makes up Alphabet City has had a strange history. The actual street names of Avenues A, B, C, and D date back to the development of the 1811 city street grid, though these Avenues didn’t extend uptown until landfill expanded the East Side of Manhattan.

Gradually the uptown lettered avenues were replaced by actual street names: York Avenue instead of Avenue A, for example, and East End Avenue instead of Avenue B. Below 14th Street to Houston Street, the letters remain.

Perhaps the ongoing non-acceptance of Alphabet City as a distinct section of the East Village has to do with the fact that like Tribeca and Nolita, it’s a name coined by clever realtors.

Still, keep in mind that the “East Village” is also considered a real estate industry invention, created in response to a sudden upswing of artists and young people moving into the tenements from Third Avenue to Avenue D in the 1960s.

Before the 1960s, today’s East Village was known as the Lower East Side. The wave of people setting up home here resulted in a cooler, hipper rebranding—meant to evoke an eastern extension of Greenwich Village, as Village Preservation explains in an excellent recent blog post.

[Third image: Wikipedia]

September 15, 2024

An 1870s painter from Queens captures the stark reality of “the way the city is built”

Charles Henry Miller didn’t intend to devote his life to painting. Born in 1842 in Gotham, he studied art but graduated from New York Homeopathic Medical College and found work as a ship’s surgeon.

Two failed mutinies during his first voyage on a Liverpool-bound ship made him reconsider his professional direction. While in England he visited European art museums, prompting him to abandon medicine for a career as an artist.

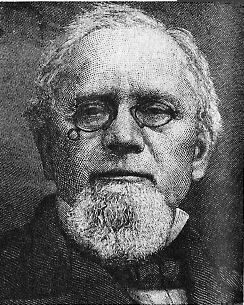

Miller became known for his lush, dreamy pastoral landscapes of a then-rural Queens, where he lived much of his adult life—earning the title “the artistic developer of the little continent of Long Island” from American poet and travel writer Bayard Taylor.

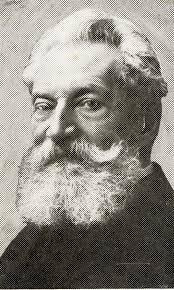

But in 1877 he apparently took a trip across the East River to the district of Harlem, which was beginning its transformation from rural country to urban city. Miller (below right) captured in stark detail a scene hardly uncommon in the burgeoning New York of the era: workers getting ready to tear down a cottage on top of a hill, ostensibly to construct multi-family tenements.

“Charles Miller had a preservationist’s interest in the historic buildings and landmarks that were rapidly disappearing throughout New York and Long Island,” states the Brooklyn Museum, which has this painting, plainly titled “The Way the City Is Built,” in its collection.

“This Harlem scene represents the modern urban landscape in transition: a hill on which stands an old cottage is being razed for the construction of more multistory tenements like the ones at right.”

New York has always been a “pull down and build over again” town, as Walt Whitman put it when describing the 1840s. But there’s more to Miller’s painting than the disappearance of spacious countryside in favor of tightly packed cityscape.

The painting highlights the contrast between the two worlds that co-existed in the late 19th century: the men in the ravine with their primitive tools and horse carts working together as beasts of burden—and then modern civilization towering before them. The future of New York belonged to the tenement builders.

[Top image: Brooklyn Museum; second image: New York Medical College]

The mystery of the copper and glass awning on a brick row house in the West Village

Nestled within the lovely brownstone blocks of Greenwich Village, one house in particular stands out to me: 152 West 11th Street, toward the end of that triangular block west of Sixth Avenue where Seventh and Greenwich Avenues meet.

In the shadow of what used to be St. Vincent’s Hospital (RIP), this Flemish-bond beauty features all the charm of an early 19th century grand row house. Yet its smaller scale gives it a homey feel: two stories plus a half-floor attic, an English basement, a short stoop, and a pretty iron fence in front.

What really sets Number 152 apart from its neighbors is the copper and glass awning over the entrance. This delicate, ornamental headpiece is unlike anything I’ve seen on similar residential buildings.

It’s hard to walk by it and not wonder who put it there. It likely wasn’t the original builder of the house, who in 1836 also put up the three houses to the left—creating an identical row of Greek Revival homes for the new, well-heeled residents of rapidly developing Greenwich Village.

Over the years, changes came to the row. The three houses at 146, 148, and 150 gained an extra floor; Number 152 served as a boardinghouse before appearing to go back to a single-family residence occupied at different times by a merchant, a doctor, the well-known stage actress Bessie Cleveland, and a Suffrage supporter who held public meetings in the house.

Later photos from the mid-20th century, like the one above, show Number 152 with its unique awning, and this old-school piece of beauty has been in place ever since.

While it’s unclear which owner decided to add it to an already stunning row house, I’m going to guess it date back to the first years of the 20th century.

The ornamental copper pieces look like petals, and this motif inspired by the natural world makes me think it’s an example of the Art Nouveau style popular in the early 1900s.

Or perhaps the awning is supposed to look like a crown, with jewels of glass that sparkle in the sun like diamonds and meant to make the house feel regal—like you’re entering a miniature palace.

[Third image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

September 9, 2024

Deciphering the brick facade of faded ads on a forlorn First Avenue tenement

The Chinese restaurant on the ground floor has shut its doors. Some apartment windows are blocked by wood boards. Graffiti mars the space below the roofline.

The tenement at 1205 First Avenue, at the corner of 65th Street, seems empty and abandoned. And the faded ads that once faced traffic heading uptown are in an equally sad state.

The Hertz ad is easy to decipher. But is that a second ad underneath it? “First look” is all I can make out. Toward the lower third of the four-story palimpsest, an entirely different ad seems to appear. All I can see are black letters.

I thought that finding an older photo of this corner would offer a view of the ads in a better state. The second photo was taken around 1940, and the facade of the building is tidy and ad-free.

My guess is that this building will be reduced to a pile of bricks in the not-too-distant future. Before it does, though, I’d love to know what the other faded ad or ads are struggling to tell us.

[Second image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

September 8, 2024

Eerie footsteps, a woman’s remains, and a mysterious ghost story in a Bank Street row house

For almost 170 years, the sweet, three-story Greek Revival row house at 11 Bank Street, just off Greenwich Avenue, has had many occupants.

Built in 1845 when Greenwich Village was a choice neighborhood in the growing city, its first owner was French-born Louis Peugnet, a former member of Napoleon’s army at Waterloo. With his brothers, Peugnet came to Manhattan and established a military school down the block from his lovely new residence, states the Greenwich Village Historic District Report.

Peugnet died in 1860, and by the 1880s the home had become a boardinghouse, according to Donna Florio in her 2021 book, Growing up Bank Street: A Greenwich Village Memoir.

Forty years later in a Village favored by artists and writers, John Dos Passos had a room here; it’s where he wrote his 1926 novel, Manhattan Transfer.

But perhaps the most curious occupant of 11 Bank Street was the ghost of a Greenwich Village woman who died in 1939. The ghost’s presence was first noted by a scientist-artist couple that moved here during the 1950s and made it their home for decades.

The ghost story starts in 1956 after Harvey Slatin, a physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project, and his painter wife, Yeffe Kimball, bought 11 Bank Street. At the time, the house was a 19-room boardinghouse long run by a Mrs. Maccario, per a 1957 New York Times article.

Once the rooms were emptied of boarders, Slatin and Kimball set about restoring the house. That’s when they began hearing strange noises, usually during the day.

“In quiet hours while they were alone or with a few friends, they thought they heard a woman’s footfalls on the steep staircases, sometimes just crossing the upper floors,” wrote the Times. “Sometimes there was a light hammering.”

The couple would go upstairs to investigate, but there was never any explanation for the sounds. “They called, ‘who’s there?’ The walls gave back the call in echo fragments,” stated the Times.

One day, their carpenter made an eerie discovery. While hammering through a top-floor ceiling, an object fell out and hit the floor as plaster and lath dust showered the ground.

It was a metal can “about twice the height of a tin of ground coffee.” The can’s label read, “The last remains of Elizabeth Bullock, deceased. Cremated January 21, 1931.” The label also listed a Middle Village, Queens address for the crematorium.

Slatin called the crematorium and discovered that Bullock, 51 years old at the time of her death, was killed in a car accident blocks away on Hudson Street. Her home address was listed as 113 Perry Street, just beside Hudson Street. (Below, 11 Bank Street, undated)

To the couple’s knowledge, Bullock had never lived in the Bank Street house. So how did her remains end up in a can in the ceiling, and who put them there? Slatin and Kimball searched for relatives who might have answers, but they came up empty.

Resigned to keeping Bullock’s remains, they decided to display the can on top of the grand piano in their brick living room. “The Slatins cannot think of what else to do with it,” the Times reported, “and there’s a chance, they think, that someone, some day, may come for it.”

How Bullock’s remains found their way into the ceiling appears to still be a mystery. But this strange ghost story doesn’t end there. In 1980, Joyce Wadler, writing in the Washington Post, picked up the story—paying a visit to Slatin and his second wife, Anne, at 11 Bank Street. (Yeffe Kimball had died of cancer in 1978.)

Twenty-three years later, Bullock’s remains were still in the can on the piano. After the New York Times article ran in 1957, Slatin and Kimball brought in a ghost expert and medium, who channeled Bullock. In an Irish accent, Bullock said that her family disowned her when she married a protestant. Her soul was not at rest because she wanted a proper Christian burial.

But the Slatins still had Bullock’s remains, and the haunting continued. Anne Slatin described Bullock as a “benign ghost” whose perfume was often smelled at parties. The ghost also liked to open closet doors unexpectedly, at which Harvey Slatin would reply, “Oh Elizabeth, go fix yourself a drink,” according to Wadler’s article.

After the WaPo story ran, a Catholic priest in California contacted the Slatins and offered a Christian burial. The couple took up the offer. Elizabeth Bullock’s ashes were interred in a Catholic cemetery on the Pacific Coast 50 years after the Hudson Street car accident that claimed her life.

Does Elizabeth Bullock still haunt those upper floors of 11 Bank Street, even though her remains are out of the house and in a Catholic cemetery in California? Only the current residents could say.

Right now, though, the house seems unoccupied, and it’s up for sale. This 19th century stunner with a spooky Greenwich Village ghost tale in its backstory can be yours for $15 million.

[Third image: New York Times; fourth image: NYPL Digital Collections; fifth image: Edmund Vincent Gillon, MCNY, 2013.3.2.75; sixth image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

September 2, 2024

Explore the stories of Riverside Drive with Ephemeral New York on a September walking tour!

Riverside Drive, opened in 1880 and intended to rival to Fifth Avenue as the home of Manhattan’s newly minted millionaires, isn’t just a breathtaking avenue for a stroll. Its mansions and memorials holds secrets and stories.

Who was the silent screen actress whose famous paramour bought her a Riverside Drive townhouse close to his family penthouse? Which steel titan built a 75-room chateau for himself, his wife, and their 20 servants?

What drove a turn-of-the-century mother with a lovely home on the Drive to launch a citywide campaign against “unnecessary noise”? Who is the real-life model at the Fireman’s Memorial who was a sensation in the early 1900s and then lived much of her long life in a mental institution?

Why did a famous author name a Riverside Park boulder after a neighborhood boy? Which still-standing mansion has a tunnel leading to the Hudson River? When did the 1840s railroad that hugged the Hudson River shoreline finally move underground?

Want insight into more stories about Riverside Drive, especially the Drive in the Gilded Age—when an eclectic mix of business titans, poets, actors, and eccentrics made this avenue of mansions and monuments their home?

Join Ephemeral New York on an upcoming walking tour! Tour dates are as follows, and tickets can be purchased by clicking the link:

Sunday, September 8: A few tickets remain for The Gilded Age Mansions and Monuments of Riverside Drive, organized by Bowery Boys Walks. Tour starts at 1 p.m.

Sunday, September 22: Sign up for Exploring the Mansions and Memorials of Riverside Drive, organized through the New York Adventure Club. Tour starts at 1 p.m.

Hope to see everyone on these fun, insightful walks up one of New York’s most beautiful avenues, made even better by the cool, breezy weather in September!

The construction workers embossed in bronze on a 1929 Art Deco skyscraper’s elevators

There’s a lot to admire about the Fuller Building, the Art Deco masterpiece completed in 1929 on Madison Avenue and 57th Street.

Sleek, streamlined, and stylish, this bold new design heralded the skyscraper age of the 20th century.

It also transformed 57th Street into an east-west business and cultural artery, with the Fuller building as one of its premier towers.

But what I want to call out is the humanity of the Fuller Building—namely the respect the tower gives to the men who built it.

Each elevator door in the gleaming lobby features bas reliefs of overall-clad construction workers hoisting the blocks of granite that form the building’s base, hammering beams, securing steel, and plastering walls.

Few faces are shown. It’s more of a way to honor the tradesmen who put the plans of dreams of developers and architects into the cityscape, transforming the look of the skyline and the vantage point through which people saw the city.

The Fuller Building memorialized the workers who built it in another way: Elie Nadelman’s sculpture of two men in front of what looks like a skyline, flanking a clock (above).

I don’t know if Nadelman had a hand in the bronze reliefs on the elevators. But honoring these workers by putting them front and center in the lobby makes sense when you realize that the Fuller company was a construction company founded in Chicago by an architect, George Fuller.

Fuller and his company were behind some of New York’s first skyscrapers, including the Flatiron Building—originally called the Fuller Building when it opened in 1902.

It feels appropriate for Labor Day to post their images—the anonymous army of people who built and continue to build the city we live in.

[Fifth image: structurae.net]

Inside a West Village passageway leading to a hidden courtyard and 1820s backhouse

Whenever I stroll through the West Village, I’m well aware that there are two versions of the neighborhood.

One is the Village of cobblestone streets, enchanting houses, and sidewalk cafes. The other is the secret Village behind brick walls, embowering trees, iron fences, and horsewalk doorways.

But sometimes you find a portal into this secret West Village. The one I came across is an arched side entrance at a sweet, three-story white stucco house at 93 Perry Street (below).

Under the arched entrance is a locked gate, which leads to a slender outside passageway that takes you to a small courtyard and a second house. This backhouse, as it’s called, feels right out of a fairy tale—with rounded windows, decorative ironwork on the fire escape, and rustic wood shutters.

Backhouses aren’t unusual in downtown neighborhoods; an estimated 75 of them still stand in Greenwich Village, according to a 2002 New York Times article. Some are visible through cracks between buildings, while others are true secrets hemmed in by buildings.

What makes this backhouse more unusual is the small, shady courtyard in front of it separating the two houses into what seems like distinct entities.

Trees and plants make the court feel more like a front yard; cracks in the stone and concrete on the ground carry an air of neglect. But the privacy it affords is a rarity in contemporary New York. What’s the story behind it?

Backhouses were typically built by the owner of the front-facing house to serve as a carriage house or a workspace. In a 19th century city with fewer housing regulations, they were also used as illegal rental units that could make extra cash for an unscrupulous owner willing to pack in boarders.

The backhouse at 93 Perry Street was built as a workspace for a carpenter who purchased this lot of land in 1811.

“Abraham A. Campbell, a local carpenter-builder, leased the lot for 21 years and built his shop on it in 1827, and his house the following year, making it his home and place of business until late in 1832 when he sold the lease ‘and the buildings thereon,'” states the 1969 Greenwich Village Historic District designation report.

Campbell bought the land under his two houses when the former country village of Greenwich was transitioning into New York City’s newest sought-after neighborhood, thanks to overcrowding and disease outbreaks in the lower city.

Selling his lease in 1832 must have netted Campbell a tidy profit, which he used to relocate to West 12th Street. The West Village continued to grow through the 1800s, and waves of new residents of 93 Perry Street reflected the more middle- and working-class population in later decades. (Above, in 1932)

As for the courtyard, like many of the alleys and lanes of the era that have been paved over and de-mapped, it may have once had a real name.

A wistful 1924 article in the New York Evening Post described the backhouse and delved into the mystery of what the writer called the “nameless” courtyard. This sketch (below) from the article captures the scene in time.

“The city ought to establish a lost-and-found department to help recapture odd little streets and courts and alleys that have wandered away like strayed waifs and lost themselves in the bewildering maze of New York byways,” read the article. “Take, for instance, one little alley just off Perry Street, past Bleecker. Everything about it is lost. Name, country, identification of any sort.”

“Some people have lived there for years, and are still at a loss for an address….Sometimes, to be sure, out of sheer necessity, the residents of Nameless alley supply the title ‘Perry Court.'”

“No one ventures a definite solution of the mystery,” the article concluded. “But there is singing from an open window where bright flowers edge the sill, and the least tinge of corned beef and cabbage is in the air. Everybody’s happy—and what’s in a name?”

One person who made note of this Evening Post writeup when it appeared was author H.P. Lovecraft. A resident of New York City in the 1920s, this horror and science fiction writer published a short story titled “He,” which involved a narrator taking a late-night, time-traveling sojourn through Greenwich Village.

“At the conclusion of ‘He,’ a passerby finds the narrator—bloodied and broken—lying at the entrance to a Perry Street courtyard,” wrote David J. Goodwin, author of the 2023 book Midnight Rambles: H.P. Lovecraft in Gotham.

In “He,” from 1925, the narrator calls it “a grotesque hidden courtyard of the Greenwich section,” as well as “a little black court off Perry Street.”

It would be strange to call the courtyard “grotesque” today, as it and the backhouse have an old-school charm increasingly difficult to find in today’s tidy, hyper-expensive West Village.

These days, the backhouse appears to be a rental building with one- and two-bedroom units—a very different setup from Abraham Campbell’s workshop in the West Village of 200 years ago.

[Sixth image: NYPL, 1932; eighth image: New York Evening Post, August 1924]

August 26, 2024

A relic of a mailbox found in Brooklyn reveals something about how New Yorkers mailed letters

The Montauk Club House is an astounding Venetian Gothic building completed in 1891—when Brooklyn was a separate city and glorious townhouses made Park Slope one of the most architectural rich neighborhoods in New York.

While taking in the beautiful interior of the building, my eyes landed on a very utilitarian old-school mailbox tucked away above a radiator near the entrance.

On it was a message, asking users to remember to use “zone numbers” before they drop their letters in the box.

Zone numbers? I was unfamiliar with the term. But a 1960 document from the Brooklyn Public Library shows a map of Brooklyn divided into neighborhoods (third image), each assigned a different zone number.

I get it now—these zone numbers are the last two digits of each neighborhood ZIP code. Yet the mailbox also carried a sticker advising users to add the ZIP code to mail addresses.

Are ZIP codes a later version of zone numbers? According to the Library of Congress (LOC), ZIP codes were introduced nationally in 1963 to make sorting mail less time consumer for postal workers and therefore speed delivery.

But the LOC also explains that assigning towns and cities a unique number wasn’t a new idea; in 1943 the United States Post Office introduced zones numbers to many cities, and as the number of zoned cities increased over the next two decades, a new system had to be established.

So it seems the mailbox is carrying two separate messages: one from the early 1960s reminding people to use ZIP codes, the other possibly from as early as the 1940s asking users to add the zone number to the address.

ZIP codes have been standard in my lifetime, but apparently the switch from no code at all or a two-digit code was a big deal to people at the time. The LOC stated that it took until the end of the 1960s for the five-digit code to become widely used.

Here’s an example of a Greenwich Village antiques shop that had store signage still noting their two-digit postal code. (Sadly, the store is gone, but I appreciated the fact that they kept the code in their address, a vestige of another era.)

[Third image: Brooklyn Public Library]

From a Gilded Age senator’s home to a 1920s speakeasy, the unusual life of a faded Midtown brownstone

Over the years I’ve often wondered about the brownstone at 14 East 44th Street, a faded dowager hidden in the shadow of the office towers around Grand Central Terminal.

Snug between its glass and limestone neighbors, it likely started out as part of a posh row of upper middle class dwellings in the 1860s or 1870s. In those decades, blocks of uniform brownstones rose all over Manhattan, especially in the upper reaches of Murray Hill and today’s Midtown.

And what’s with the three-story facade covering the original stoop and parlor windows, slapped on to give the brownstone a more stylish appearance, I gather? It’s as if a new owner began redoing the brownstone with Romanesque touches and then gave up.

The research didn’t lead me to the brownstone’s origin story or an explanation of its strange facade alteration.

But it did reveal stories about the prominent New Yorker who occupied the house in the Gilded Age, and then the bizarre turn the brownstone took in the 1920s as a speakeasy set up by the federal government to trap bootleggers bringing liquor to Gotham.

First, the late 19th century owner who lived here with his family. Webster Wagner (at left) was a state senator who made his fortune in the railroad business—not by buying rail lines (like his close friends, the Vanderbilts) but as the inventor of the sleeping car.

A native of upstate New York, Wagner had a spectacular mansion in Palatine, near Albany, and a “very nice house in New York City, in which his family spent winters,” notes this biography.

When Wagner and his family—his wife, son, and four daughters—took up residence in this uptown brownstone isn’t clear. But they held a splendid wedding reception for his youngest daughter, Annette, here on December 2, 1880 after a ceremony at Holy Trinity Church on Madison Avenue and 42nd Street.

With 1,500 invitations sent out, it was deemed by the New York Times as one of winter’s foremost society nuptials.

“The reception from 8:30 until 11 o’clock was almost a crush,” the Times reported, after chronicling the stunning floral decorations in the house’s two parlors. “One could scarcely move without running against a senator, elbowing a railway president, or nudging a millionaire.”

As he did with his other married offspring, Wagner gifted the newlyweds with a house of their own, “a magnificent up-town residence in the immediate neighborhood of his own,” wrote the Times.

Wagner lived in the brownstone until his death in 1882, ironically in a terrible train collision at Spuyten Duyvil as he was returning home from Albany. His grief-stricken family received throngs of guests in the same parlors where Annette’s wedding was joyously celebrated two years earlier, reported the New York Times.

Through the end of the Gilded Age and the early decades of the 20th century, the brownstone changed hands. by 1920, Prohibition arrived. Taverns and bars were forced out of business—and hundreds of speakeasies appeared in the city with no shortage of thirsty customers eager to enjoy New York nightlife with alcohol.

That began the former residence’s second life as a secret bar (above, in 1927). When it opened in 1925 as “The Bridge Whist Club,” it seemed like a regular Midtown speakeasy—even somewhat chic, as this newspaper illustration above shows. The place was close to the action on Broadway, and the “club rooms” operated on the second floor.

“The saloon was filled with smoke and the jabbering of customers lining the mahogany bar,” wrote a reporter for a wire story. “Bartenders buzzed about filling schooners with real beer, chipping ice for martinis and Manhattans. In the curtained back room, men with girls whose cheeks were coated with rouge yelled drunkenly for more champagne.”

But apparently, bootleggers began to catch on that something wasn’t right with the place. Every time they came to deliver alcohol, it was “mysteriously seized,” as one 1926 news story put it.

Soon a story emerged. After the owner sublet the profitable speakeasy, it fell into the hands of A. Bruce Bielaski, part of a Treasury department prohibition enforcement unit that used wiretaps and eavesdropping devices stashed in lamps to snare “Prohibition violators,” according to Burton W. Peretti in his book, Nightlife City: Politics and Amusement in Manhattan.

The Bridge Whist Club “violated the Volstead Act in the name of its enforcement of too many pathbreaking ways for Washington or the public to accept,” wrote Peretti. “Those arrested at the club were ultimately set free.”

By the 1940s, 14 East 44th Street went in another direction: it became the site of a restaurant and club called Gamecock. Through the 20th century, the upper floors seem to have transformed into office space, and in recent years the ground floor served as a deli-restaurant, now closed.

These days, the brownstone has its cornice and window lintels intact, though the glamour that attracted Webster Wagner and the speakeasy crowd has faded away. It’s the lone surviving brownstone on the block and witness to more than 150 years of city life, and the house has more stories to tell.

[Third image: The Silent Forgotten via Findagrave.com; fifth and sixth images: Elmira Star Gazette; seventh image: The Brooklyn Citizen]