Jonathan Clements's Blog, page 283

July 11, 2021

How to Choose

But there���s more to it than that. Long-term care is also an emotional topic. There���s the expression that personal finance is more personal than it is finance. I���ve been reminded of that over the past few weeks, as a number of people have contacted me to share their stories about long-term care. Some have described frustrations with these policies, including rising rates and bureaucratic obstacles to making claims.

Meanwhile, others have hailed LTC policies as lifesavers for their families. As one person put it, it���s been hard enough to manage the health challenges of her husband���s disability. But with LTC coverage, at least they've been spared financial stress, which would have made a bad situation that much worse. As challenging as these policies can be, they can also be immensely valuable.

These days, it���s much��harder��to find a standalone LTC policy. That���s because, as I mentioned in my earlier article, insurers got the pricing wrong when these policies became popular in the 1980s. For that reason, if you have an older policy, it���s often worth trying to maintain it. But if you have to compromise at renewal time to minimize premium increases, this is how I would think about the choices. You could also use this as a guide if you���re shopping for a new policy.

Daily maximum.��This is the fundamental element of an LTC policy. I���ve seen benefits that vary widely���from just $100 a day to more than $400. That���s an awfully wide range. Here are the factors I���d consider as you zero in on an appropriate coverage level:

Cost of care in your area. Christine Benz, Director of Personal Finance at Morningstar, compiles a set of LTC��statistics each year. That���s the best starting point for getting a handle on the cost of care. As you���ll see, costs vary widely from region to region. A private room in a nursing home in New York, for example, costs nearly three times what it costs in Louisiana.

Health outlook. No one has a crystal ball. But as you get older, this is one area where you have an information advantage relative to the insurance company.

Marital status. If you���re married or you have children nearby, they may be able to help you later in life, thus reducing your need for paid care.

Also if you���re married, it���s important to note a difference between the needs of men and women. Because husbands tend to be older than their wives and because women, on average, live longer than men, men are generally less able to provide care for their wives than the other way around. This shows up in the Morningstar statistics as well. Women account for nearly 70% of residents in long-term-care facilities and their stays are 70% longer. If you have to choose, you'd want to buy more coverage for a woman than a man.

LTC poses the biggest challenge for people who are in the middle financially. If you���re of very modest means, Medicaid might pick up the cost of long-term care. If you���re very wealthy, you likely wouldn���t have a problem paying the tab yourself. My recommendation: Use the statistics referenced above to estimate the cost for a multi-year stay in a long-term facility in your area. Then ask yourself how feasible it would be to cover that cost yourself.

Inflation protection.��Some LTC policies include inflation protection that���s generous by today���s standards���as much as a 5%-a-year increase in benefits. But this option will make a policy materially more expensive. My advice: If you���re on the younger side, inflation protection is worth paying for. But if you���re older, you might forgo that option since, for better or worse, there are fewer years of inflation to worry about.

Coinsurance.��Some policies offer a coinsurance option, whereby the policyholder would share the cost of care with the insurer. In exchange, the premium would be lower. Who would this help? If you look at the statistics, you���ll notice that only a small fraction of seniors incur costs in excess of $250,000���numbers range from��9%��to��15%. Coinsurance would be a good option for many families in the financial middle���who might be able to afford $200,000 of care, but not $2 million.

Elimination period.��This refers to the period of time before benefits kick in. Most policies have a relatively short elimination period of 100 days. But this is an area where you might compromise. Unfortunately, there���s no such thing as an LTC policy that provides a multi-year elimination period. I think that���s unfortunate because, according to Morningstar's Benz, that's just the type of coverage many people say they want���basically, catastrophic coverage. Insurers would like to offer it, but Benz notes that insurance regulators won���t let them. Absent that, the best you can do is to choose the longest elimination period an insurer offers.

Benefit period.��This one is tricky. According to the statistics, the average long-term-care claim is about three years. But that figure is distorted because many policies cap the benefit period. As a result, policyholders contending with these caps try to wait as long as possible���and probably longer than they���d like���before claiming benefits. In other words, the average claim would be longer if insurance policies didn't have these caps.

My advice: Try not to compromise on the benefits period. This would protect you in the case of a protracted illness. An added benefit: Premium payments cease the moment you claim benefits. If you have a long or unlimited benefits period, you could claim benefits��and��stop paying premiums as soon as you qualify for even a modest level of care.

If you don���t have a long-term-care policy, what are your options? As I noted, it might not be a problem if you have assets that are either very modest or very substantial. But even if you fall in the middle, all is not lost. First of all, the statistics say you might not need paid care at all. About��50%��of people don���t. And if you do, you might be able to��afford it��out of pocket.

Beyond that, Christine Benz suggests some other strategies: If you have home equity, you could plan on a reverse mortgage. If you have a whole-life insurance policy or an annuity, an intriguing option is to��swap it��for a hybrid life-LTC policy using what���s known as a 1035 exchange. There is, of course, no magic bullet. But it���s worth making a plan. That way, you���ll be ready if the need arises.

Adam M. Grossman��is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman��and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman��is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman��and check out his earlier articles.The post How to Choose appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 10, 2021

Keeping Our Heads

Despite all the hand-wringing, this doesn���t strike me as an especially dangerous time to own stocks. Corporate earnings are rapidly recovering from last year���s economic shutdown���not exactly a scenario where you���d expect a big stock market decline. Meanwhile, bonds and cash investments are offering scant competition for investors��� dollars, which is another reason to be bullish on stocks.

But even if the overall market appears no riskier than usual, there���s a danger that we���ll put ourselves in financial peril���by falling into one of these three behavioral finance traps.

1. Overconfidence. As financial markets rise, so too does our confidence. There���s nothing like making great gobs of money to make folks think they���re smarter than they really are. What if their results are mediocre compared to the market averages? Investors are often blissfully unaware���and simply assume they���re beating the market.

One indicator of our collective overconfidence: Average daily stock market trading volume in 2020 and 2021 has been running 63% above 2019���s level. When investors trade, it���s typically a sign they feel they know what they���re doing. But all that trading is costly. Sure, we might not pay a commission when we buy and sell stocks. But we still lose money to the bid-ask spread, the slight difference between the price at which we can currently purchase a stock and the lower price at which we can sell.

Even more worrisome, overconfidence can lead us to make big, undiversified investment bets. For some, those big bets will pay off handsomely���but, for most, the result will be market-lagging returns. How can I be so sure? Almost every year, the stock market averages are skewed higher by a minority of stocks that post spectacular gains, leaving most stocks with market-lagging performance. If we aren���t lucky enough to own the big winners, we���re destined for subpar returns. This is a reason to own total market index funds, which ensure we own all stocks, including each year���s superstars.

2. House money effect. Overconfidence can lead us to make risky investment bets. Adding fuel to this fire: the house money effect. What���s that? Think of casino gamblers who get lucky early in the evening. They now feel like they���re ahead of the game and playing with the house���s money���and that can prompt them to make even bigger bets.

The same thing happens with investors. After the spectacular U.S. stock returns of the past decade, many investors are financially far ahead of where they expected to be. The danger: They figure they can afford to take yet more risk by, say, dabbling in individual stocks or taking a flier on cryptocurrencies���and those bets could come back to haunt them.

Over the past year, we���ve seen a variation on the house money effect, and I suspect it���s especially prevalent among newbie investors. Their surprise windfall came not from the market, but in the form of stimulus checks and lower spending during the pandemic. They���ve taken this ���found��� money and started dabbling in meme stocks, dogecoin, Tesla and goodness knows what else.

Two decades ago, I fell prey to a similar phenomenon. In the late 1990s, I received $8,000 when my father cashed in a life insurance policy on which I was a co-beneficiary. Emboldened by both this windfall and that era���s euphoria, I strayed from my usual indexing strategy and used that $8,000 to buy four individual stocks. One company got taken over at a handsome premium. Two performed okay. And one plunged almost overnight���and I bailed out when the stock was down some 80% from my purchase price and on its way to zero. I haven���t owned an individual stock since, except a few hundred shares of my last two employers.

3. Extrapolating returns. Last year, many investors crowded into some of the market���s highest fliers, including Peloton Interactive, Netflix and��Tesla, only to see these stocks struggle in 2021. In many cases, it seems folks were buying these stocks simply because they���d gone up and they naively assumed those gains would continue.

But these days, investors don���t just chase performance. They also flock to the internet to loudly proclaim their devotion and get encouragement from others, all this leading to dangerous herding behavior. For instance, earlier this year, the higher cryptocurrencies climbed, the more virulent supporters became���only to fall almost silent during the recent rout. This phenomenon even infects staid value investors. These folks have been notably quiet in recent years. But with value outperforming growth in 2021, those whose portfolios have a value tilt are more likely to mention it in public.

Some degree of investment conviction is a good thing. It helps us to stick with our portfolio when markets turn rough. But we shouldn���t let conviction morph into blind loyalty. Today, folks will defend their favorite investments with a fervor usually reserved for a local sports team or a preferred political party. But no undiversified investment deserves that sort of undying love.

As I mentioned in an article earlier this year, thanks to the market���s efficiency, there���s no reason to think professional investors will be any more successful than amateurs at picking winners. Instead, I believe the hallmark of professional investors���as well as prudent amateurs���is that they think more about risk.

We���ve seen the S&P 500 climb 16% this year, ignoring dividends. But we���ve also seen some much-ballyhooed investments badly stumble, with Tesla down 27% from its high, bitcoin off 48% and ARK Innovation ETF down 21%. The lesson: The market giveth���but, if we behave foolishly, it���s all too easy to see those gains taken away.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

"A coach I worked with asked me how things were going," recalls Don Southworth. "My team wasn���t doing too hot and I wasn���t doing too hot, either. After a few minutes, she said, 'Ah, you're being your results'."

Want to reduce the risk that a cyber-thief empties your financial accounts? David Powell offers a five-step protection plan.

"For retirees, what matters isn���t the size of their nest egg, but the lifestyle it can support���and I fear $1 million won���t support the lifestyle it once did," writes Aaron Brask.

When the McClatchy Company filed for bankruptcy last year, that put at risk Greg Spears's small pension from his time as a newspaper reporter. Here's what happened next.

Dennis Friedman likes to hide cash around the house���but he doesn't like it sitting in his portfolio. Sound odd? Dennis explains his thinking.

"One of the reasons our economy has been a success is our acceptance of failure," says Joe Kesler. "If��bankrupt entrepreneurs are��excessively punished, they may give up on high-return opportunities."

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier��articles.

Jonathan Clements is the founder and editor of HumbleDollar. Follow him on Twitter @ClementsMoney and on Facebook, and check out his earlier��articles.The post Keeping Our Heads appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 9, 2021

Lending a Hand

I was only 22 years old when I had my first shocking experience with the power of money to cause a life to self-destruct. I was working as one of the federal government���s national bank examiners. A teller���s cash drawer was missing money and she was sent home.

Around lunchtime, the bank president realized his truck was also missing. The teller had stolen his truck, and then driven for several hours before stopping and attempting to end her life. Fortunately, she wasn���t successful.

But the experience made a big impression on me. Money is a double-edged sword with the power both to help fulfill our aspirations and to destroy. How can we help those who are struggling? Try these three steps.

1. Strive to be a ���financial first responder.��� That���s the label I give to those willing to help others in financial difficulty. We know that depression can occur in those suffering from too much consumer debt. If not addressed, serious consequences often result.

In such situations, there are time-tested methods to give people hope. It doesn���t take an MBA to help those who have too much credit card debt. Just like we learn first aid to assist with a medical need when a doctor isn���t around, anyone can learn some basics to help financially stressed people who can���t afford professional help.

I���ve trained others with materials from organizations like Crown��Financial Ministries. The goal is to lay out a series of small, manageable steps that can be used to gain financial peace of mind. The first step might be to find a way to save $500. It���s something almost everybody can accomplish, and it gives them the confidence to move on to the next step of reducing debt. Crown���s money map is a brilliant formulation of baby steps to give those in deep debt hope that there���s a way out.

2. Redefine failure as a virtue. One of the reasons our economy has been a success is our acceptance of failure. For much of human history, debtors who couldn���t pay their loans went to prison. But in America, we made bankruptcy relatively easy so folks could discharge their debts and start over.

You might think, as a banker, I���d prefer the harsh debtors��� prison method. But there���s real value to society, as well as to the individual, in making bankruptcy less severe.

If��bankrupt entrepreneurs are��excessively punished for failure, they may give up on high-risk but potentially high-return opportunities. Think Henry Ford, who had two companies go bankrupt before he succeeded. Or Walt Disney, who was fired by an editor because he had no imagination. Or Mark Cuban, who failed as a waiter, carpenter and cook before finding success.

High-tech firms like Amazon believe if they aren���t trying and failing with new ideas, they aren���t maximizing long-term value for shareholders. The list of failed Amazon ventures is remarkable. Amazon Fire smartphone lost $170 million before being shuttered. Kozmo.com was a $60 million dollar write-off. There are many more.

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has a high view of failure���s value: ���I believe we are the best place in the world to fail (we have plenty of practice!), and failure and invention are inseparable twins." We need to remind ourselves and others that there shouldn���t be shame in failure, but there might be regret in being too fearful to try new initiatives.

3. Remember the limits of money and the value of life. I became a bank chief executive in my mid-30s. I was driven to achieve great numbers. When something or someone got in the way of that objective, I could lose perspective.

Fortunately, I worked with a bank attorney named George who had flown multiple missions over Germany during the Second World War. He had the perspective to distinguish between what was really important and what was a temporary problem.

One day, my bank discovered a customer had sold ���encumbered��� assets without first paying off the bank loan that was secured by those assets. Even worse, he lied to the bank, saying he still had the collateral. George and I met with the customer and his lawyer.

As the start of the meeting, the customer began talking. He was completely broken. In tears, he shamefully admitted his deception. He was looking at financial ruin and possible criminal charges. But I was mad and less than sympathetic. Fortunately, George took over the meeting.

Rather than beat the guy up, George sensed the man was suicidal. George comforted him with assurances that he could get through this situation. I remember George telling him, ���You know, in a few years, no one will even remember this happened. We have to get through this, but you will have a life once it���s over.���

I���ve heard a lot of sermons where a preacher taught the Christian virtue of loving those who have wronged us. But that day, George taught me that lesson more effectively than any preacher could. With George���s encouragement, the customer got through his problems and went on to lead a productive life.

In the years that followed, I had to deal with many problems created by bad money decisions by my employees and customers. But I never forgot that lesson I learned from George. Thanks to him, I found I was able to show a little more humanity in dealing with financial problems.

Joe Kesler is the author of

Smart Money with Purpose

and the founder of a

website

with the same name, which is where a version of this article first appeared. He spent 40 years in community banking, assisting small businesses and consumers.��Joe served as chief executive of banks in Illinois and Montana. He currently lives with his wife in Missoula, Montana, spending his time writing on personal finance, serving on two bank boards and hiking in the Rocky Mountains. Check out Joe's previous articles.

Joe Kesler is the author of

Smart Money with Purpose

and the founder of a

website

with the same name, which is where a version of this article first appeared. He spent 40 years in community banking, assisting small businesses and consumers.��Joe served as chief executive of banks in Illinois and Montana. He currently lives with his wife in Missoula, Montana, spending his time writing on personal finance, serving on two bank boards and hiking in the Rocky Mountains. Check out Joe's previous articles.The post Lending a Hand appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 8, 2021

Comforts of Cash

You might ask, ���Why in the world would someone have so much cash lying around the house?��� I keep it on hand in case of an emergency. For instance, earlier this year in Texas, the electrical power grid was severely damaged by winter storms. Because the power was down, some Texans couldn���t get access to money through an ATM or even use their credit cards to purchase food.

I live in California, where we occasionally have earthquakes. The possibility of a natural disaster happening here is real. I think everybody should have some cash readily available for the unexpected.

I know some people dislike carrying cash, but I���m not one of them. I like to carry a wad of bills because you never know when you might need the real stuff. My wife and I went to a farmers��� market the other day where many vendors don���t accept credit cards. Luckily for us, I had cash to pay for our purchases.

When I have my car worked on, my mechanic gives me a discount if I pay in cash or with a check. He���s always willing to pass along the savings on credit card transaction fees to his customers. Sometimes, I pay in cash when I���m visiting one of our favorite independent restaurants, knowing in a small way it might help their bottom line.

Although I believe cash is useful in pursuing short-term goals, I would never keep a significant amount in my investment portfolio. Compared to bonds and stocks, you just don���t earn a lot on cash investments like a money market fund or a savings account. Result: I use cash primarily for our emergency fund that covers six months of living expenses.

What you can expect to earn on the three major asset classes���stocks, bonds and cash���depends on the risk level of those investments. The higher the risk, the greater the reward an investor expects as compensation for taking on that risk. Since there���s practically zero risk in cash investments, you don���t earn much.

When you look at the average return of the three asset classes, you find their ranking is determined by their level of risk. A Vanguard Group article��showed how the three asset classes differ in risk and reward.

Cash investments

Main risk: Losing ground to inflation

Long-run average return: 3.5% a year before inflation, 0.6% a year after inflation

Percentage of years with negative returns: 0%

Bonds and bond funds

Main risk: Rising interest rates

Long-run average return: 5.5% a year before inflation, 2.5% a year after inflation

Percentage of years with negative returns: 16%

Stocks and stock funds

Main risk: Stocks can suffer severe losses

Long-run average return: 10.2% a year before inflation, 7.1% a year after inflation

Percentage of years with negative returns: 28%

As you can see, holding a large amount of cash will likely reduce your rate of return over time. There���s no free lunch in investing. If you want to earn a decent return on your money, you need to take some risk. Asset allocation���your basic mix of stocks, bonds and cash���plays a crucial role in an investment portfolio���s performance.

Here���s a general rule of thumb: If you need money in less than a year, keep it safe in cash investments. If you don���t need money for more than 10 years, invest in stocks. If your need for money falls somewhere between these two points, use a mix of bonds and stocks that squares with your financial goals and tolerance for risk.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor's degree in history and an MBA. A self-described "humble investor," he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. Check out his earlier��articles��and follow him on Twitter @DMFrie.

Dennis Friedman retired from Boeing Satellite Systems after a 30-year career in manufacturing. Born in Ohio, Dennis is a California transplant with a bachelor's degree in history and an MBA. A self-described "humble investor," he likes reading historical novels and about personal finance. Check out his earlier��articles��and follow him on Twitter @DMFrie.The post Comforts of Cash appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 7, 2021

Getting My Due

This is the story of what happened to our benefits after the pension plan failed.

For 10 years, I was lucky enough to cover Washington, DC, as a newspaper reporter. It was a heady job for a history major like me. The icing on the cake was I worked long enough to qualify for a small pension from my employer, Knight Ridder.

I left Knight Ridder in 1994. My benefit was projected to be $400 a month starting when I turned age 65 in March 2021. Heftier payments go to those who stay decades, including their highest-earning years. Still, I felt lucky to have any benefit at all. After all, a pension is guaranteed income. I would get paid no matter what.

Or that was the theory���until the newspaper business crashed so spectacularly.

At first, just a trickle of advertisers and readers migrated online. Recognizing the threat but unable to check it, Knight Ridder sold itself at a premium to a smaller newspaper chain, the McClatchy Company, in 2006. To swing the deal, McClatchy borrowed heavily and assumed all of Knight Ridder���s debts and pension obligations. You can see where this is headed. As the trickle to the internet swelled to a torrent, no number of painful layoffs and cutbacks could staunch the losses. McClatchy filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy reorganization on Feb. 13, 2020. It asked the court to terminate the employee pension plan.

Was my pension lost before it began? I turned to my old benefits handbook. If the pension plan were ever terminated, it stated, ���The amount of your payment (if any) will depend on: plan assets, the terms of the plan, and the benefit guarantee of the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC).��� This little federal agency would prove to be my biggest ally.

The PBGC takes no money from general tax revenues. Instead, it collects yearly insurance premiums from employers that sponsor private pension plans. In 2020, the agency paid benefits to more than 984,000 retirees whose pension plans had failed. After selling all its assets, McClatchy had $1.3 billion in its pension pot. That seems like a lot, but it���s $1 billion short of what���s needed to pay all of us ink-stained wretches what we���re owed, according to the PBGC.

Happily for us, the agency announced it would pay the shortfall from its insurance fund. All I had to do was apply for benefits a few weeks before I turned 65. The application paperwork was easy, apart from having to locate old records like my marriage license. And it was paperwork: We corresponded mostly by mail, which made my wait for the PBGC reply suspenseful.

A letter brought the good news less than a month before I turned 65. Yes, the company records showed that I qualified for a pension. The agency said I could get $400 a month if I took my pension as a single-life annuity, meaning all payments would end when I die. I applied instead for a monthly benefit of $333 that will be paid over both my and my wife���s lifetimes. An online calculator suggested this could yield the largest payout. Did I make the best choice? You���ll have to ask our executor���but not for a few decades, I hope.

By my mental accounting, my small pension will help pay the utility bills while I delay taking Social Security until age 70. In the meantime, we live comfortably on our savings and my wife���s earnings from work. I feel I did nothing to earn this happy ending except reaching the magic age of 65 and living in a nation with strong retirement laws.

That regulatory framework came into existence with the sweeping Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), signed into law by President Gerald Ford in 1974. Ford was portrayed as a bumbler on Saturday Night Live, raising a drinking glass to his ear when trying to answer the phone, then tripping all over the furniture. When I was a reporter, I interviewed Ford long after he was president. (Didn���t I say it was a great job?) Square-jawed and fit, he was articulate and well-informed on every issue I raised. Afterward, I told colleagues that I thought Ford was underrated. With my pension safely in hand, I feel even more sure of it now.

Greg Spears worked as a reporter for the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau and Kiplinger���s Personal Finance magazine. After leaving journalism, he spent 23 years as a senior editor at Vanguard Group on the 401(k) side, where he implored people to save more for retirement. He currently teaches behavioral economics at St. Joseph���s University in Philadelphia as an adjunct professor. The subject helps shed light on why so many Americans save less than they might. He is also a Certified Financial Planner certificate holder.

Greg Spears worked as a reporter for the Knight Ridder Washington Bureau and Kiplinger���s Personal Finance magazine. After leaving journalism, he spent 23 years as a senior editor at Vanguard Group on the 401(k) side, where he implored people to save more for retirement. He currently teaches behavioral economics at St. Joseph���s University in Philadelphia as an adjunct professor. The subject helps shed light on why so many Americans save less than they might. He is also a Certified Financial Planner certificate holder.The post Getting My Due appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 6, 2021

Not Just a Number

Even if we focus only on the financial side, we can���t sum up retirement with a single number. Many people have historically relied on the 4% rule���the so-called safe withdrawal rate (SWR). Based on William Bengen���s pioneering research, this rule says we should be able to withdraw 4% of our portfolio in the first year of retirement, and thereafter increase that dollar amount each year by the inflation rate, without running out of money. For example, if we have a $1 million nest egg, we could take out $40,000 (4% of $1 million) in the first year. If inflation is running at 2% a year, we���d withdraw $40,800 ($40,000 x 1.02) in year two, and so on.

The 4% rule was determined by figuring out what withdrawal rate would have been successful historically even in the worst markets. Since Bengen���s original 1994 study, he and others have introduced updates to his methodology that increased the SWR by improving a nest egg���s diversification.

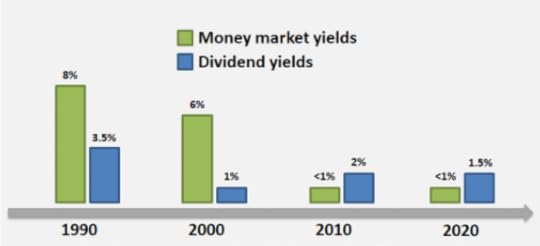

On the other hand, studies have also highlighted the link between stock market valuations and withdrawal rates. In other words, expensive markets may require withdrawing less each year. Current bond interest rates and stock dividend yields are both near their historical lows, as you can see from the accompanying chart. This concerns me���and it may require a withdrawal rate lower than 4%.

To be fair, such caution may not be necessary for three reasons. First, for many seniors, retirement income isn���t solely a function of interest and dividends. It also involves chiseling away at principal itself. That said, relying on principal means worrying about sequence-of-return risk���the danger that market prices will be down sharply when we need to sell to fund retirement spending.

Second, low dividend yields may not be the warning sign they once were. Over the past few decades, there���s been a trend toward returning corporate cash to shareholders via stock buybacks. Combine those buybacks with cash dividend yields, and the total yield on stocks doesn���t look so alarming. Buybacks may just result in getting less dividends now, but faster dividend growth in future.

Third, inflation may remain low. Bengen has pointed to inflation as being ���the retiree���s worst enemy.��� If this enemy is weakened, that���s all the better for retirees. Recent headlines and bond market volatility have reflected renewed concerns about inflation. But if the multi-decade trend toward lower inflation continues, this could minimize one of the worst threats to retirees who use the 4% rule.

How am I advising my clients? It depends on someone���s age and time horizon, but I���m more likely to suggest withdrawal rates closer to 3.5%. The implication: $1 million isn���t what it used to be. For retirees, what matters isn���t the size of their nest egg, but the lifestyle it can support���and I fear $1 million won���t support the lifestyle it once did.

Aaron Brask is an investment advisor based in West Palm Beach, Florida. His practice and research focus on low-cost, tax-efficient strategies for investing and retirement. Outside of work, Aaron enjoys sports, traveling, and spending time with his wife and two young children.

Aaron Brask is an investment advisor based in West Palm Beach, Florida. His practice and research focus on low-cost, tax-efficient strategies for investing and retirement. Outside of work, Aaron enjoys sports, traveling, and spending time with his wife and two young children.The post Not Just a Number appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 5, 2021

Losing It All

Today, Sutton���the Babe Ruth of robbers���wouldn���t waste time knocking over banks. Trillions of dollars held in millions of internet-accessible retirement and brokerage accounts are much softer and more lucrative targets. He���d use a cyber-heist known as an account takeover. For that, our modern Willie Sutton would access your account with your weak and often reused��password (the one in that massive ��leak) or by stealing your password when you click on links in his spear��phishing outreach. In a typical takeover, Sutton would log into your account, link a bank account he controls to yours and then start transferring cash out. All while sipping espresso.

But that won���t happen to your online retirement accounts, right?

In a recent��incident, elderly grandparents in Illinois had $40,000 wired out of their hijacked Fidelity Investments account. They discovered the theft long after the money had vanished by wire transfer into a bank account that the attacker had linked to theirs. The money was then transferred again and lost forever. It seems investors don���t need to dump their retirement savings into cryptocurrency or lottery tickets to lose it all. Instead, just sign up for online access to your investment accounts.

Was the couple reimbursed? At first, the answer was ���no��� because they reported the incident long after the deadline in their account agreement. On top of that, they hadn���t enabled certain security features that would have made it harder to change account contact information or to add additional linked bank accounts to their investment account.

Who bears the cost of these sorts of incidents is highly dependent on circumstances. There���s little consistency in cybercrime fraud policies across mutual fund and brokerage firms, and no industry-wide insurance system that pools risk and reimburses losses. Investment firms aren���t keen to bear the full burden of liability unless you���ve used certain security features on their site���many of which are off by default. This feels a bit like an automaker that sells cars with seat belts and airbags that are optional, and then accuses customers injured in car crashes of negligence.

Want to reduce the risk of loss? Here are five habits that���ll help protect you and your investment company:

1. You keep your devices and network secure. Strong security must start here. On each device used for account access, you have an operating system that's current with the latest security fixes. Ditto for your web browser. You���re using anti-malware software on each device. Your home network is protected with a firewall. Its wireless network is not open and uses the latest wi-fi security (WPA2 or WPA3, never WEP).

2. Your account passwords are strong, site-specific and never shared with anyone. In a strong security world, you���re using a good quality password��manager to generate the longest random password that each account���s website or app will support.

3. You protect sensitive accounts with multifactor authentication (MFA). Your investment and bank accounts are ideal places for MFA, but so too is your email account, cell phone service account and password manager.

On mobile devices, facial or fingerprint recognition can be used for MFA. For MFA, you can also use hardware security keys like YubiKey, which are highly secure, pretty cheap, durable, easy to use, and work with virtually all devices and browsers. Get at least two to avoid locking yourself out when you lose one. Companies like Vanguard Group and Bank of America support security keys that meet industry standards, and more are expected. Until then, you can still get short security codes from your financial firm via text message or an authenticator mobile app, which is less secure but better than no MFA at all.

4. You reduce your risk exposure. You never use public computers or public wi-fi networks to access financial accounts. When someone calls claiming to represent your bank or investment company, you hang up and call back the firm at the phone number on your recent statement or send a secure message within the firm's mobile app or web site. You���re vigilant for oddities in emails or text messages which tip off a phishing attack.

5. You closely monitor your account balances. Ideally, you���ve configured each account to notify you of all transactions, as well as security sensitive operations like adding a new bank account, changing the address or phone numbers on record, or cash transfers out. Even with that, it���s wise to check balances at least monthly to avoid reporting an incident past any required notification period.

Nothing in this world is perfectly secure, but habits like these put you at less risk of falling victim to this century���s Willie Sutton. Showing you���ve taken care with security will also help you avoid accusations of gross negligence, which may lead to a more favorable outcome if a bad incident happens.

This critical thinking goes both ways. Choose to keep investments with companies that are secure themselves���tricky, as there are no industry scorecards. Also favor firms that have clear and reasonable fraud protection policies, and that are helping their customers get and stay more secure with convenient, state-of-the-art technology.

David Powell has spent his career writing software and leading engineering teams. During��his 40 years working in tech, he has come to respect the limits of human imagination in any planning. Follow David on��Twitter @AmpedToGo��and check out his earlier articles.

David Powell has spent his career writing software and leading engineering teams. During��his 40 years working in tech, he has come to respect the limits of human imagination in any planning. Follow David on��Twitter @AmpedToGo��and check out his earlier articles.The post Losing It All appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 4, 2021

Don’t Be Your Results

I realized on the first day that I was probably the youngest player. Despite my rustiness, I was putting for birdies on both of the first two holes. I told my playing partners that was highly abnormal. At the end of the day, my 88-year-old playing partner���who is the oldest in the league���beat me by 10 shots. The next week, he beat me by 20. After another playing partner ���complimented��� me by saying, ���I would rather play with a nice golfer than a good golfer,��� I decided it was time to take lessons for the first time in 25 years.

After watching me hit four or five shots, the pro told me I was standing over the ball the wrong way. He adjusted my feet. The ball started flying straighter. It seems I���d been playing the game for 50 years, occasionally with some success, and yet didn���t know how to stand correctly. Later in the lesson, he showed me how I was swinging with my arms and not my body. Despite feeling really weird when I swung the club the ���right way,��� the ball started going farther. On the rare instances when I stood correctly and swung correctly, someone watching me might have thought I actually knew how to play.

I finished my three lessons last week. The pro complimented me on my progress, and I felt pretty good. When the pro was at my side and pointed out what I did wrong and right, I hit the ball really well. Going out to play on the course did not lead to quite the same results.

Maybe that���s because I don���t do the drills and exercises as much as I���m supposed to. Maybe it���s because three 45-minute lessons can���t compete with 50 years of mediocrity and mistakes. Maybe it���s because learning takes longer than I���d like. Probably all three. Still, along the way, I���ve been learning and relearning things that will help my golf game and hopefully my life���including these three lessons.

1. Old dogs can learn new tricks. One of the challenges many of us face as we get older is that we don���t think we need���or are able���to learn new things. Sometimes our success and station in life convince us we don���t need help. Sometimes we���re too embarrassed or afraid to become a student again.

I often turn to the Buddhist monk Shunryu Suzuki���s book Zen Mind, Beginner���s Mind to remember how to meditate���and to live. He writes, ���The goal of practice is always to keep our beginner���s mind. In the beginner���s mind there are many possibilities, in the expert's mind there are few.��� This is true in golf, meditation and virtually everything in life.

2. Ask for help. This may seem to be the same as No. 1���but not really. I know people who constantly read books and search the internet for wisdom and ideas on everything from investing to cooking to golf. We���re fortunate to live during a time when we can do so. But many of those people would never dream of asking someone, whether it be a coach, an expert or another living human being, to give them advice.

Sometimes we���re too cheap, sometimes we think we can do it ourselves and sometimes we just don���t like to ask. I know, because sometimes I���m one of those people. As someone who occasionally coaches and consults, I know how difficult it can be to ask for and then follow someone���s advice. I have a friend who���s taking golf lessons via YouTube videos. It might work. But I prefer a more personalized approach.

3. Don���t be your results. I learned this lesson when I was in my early 20s and started in sales. When I became a sales manager, a��coach I worked with asked me how things were going. My team wasn���t doing too hot that month and I wasn���t doing too hot, either. After a few minutes, she said, ���Ah, you're being your results.���

I had no idea what she was saying. But she reminded me that a common trait of salespeople is they become their results. When the numbers are good, they feel good and their life is okay. When the numbers are bad, their life is bad, too. I���ve since learned salespeople aren���t the only ones who suffer from being their results.

I would be my results at times when I became a minister and Sunday attendance rose or declined. I sometimes do it now when my retirement portfolio goes up or down. I���ve been doing it lately on the golf course when my score doesn���t reflect the artistic beauty of my new golf swing.

We often forget that we���re human beings and not human doings. We sometimes do the ���right��� things and the consequences aren���t what we���d hoped for. We forget that the being is often more important than the doing. We aren���t making enough money fast enough, so we take on too much risk. We have a dry spell as a salesperson, so we start fibbing a bit to our customers in the hopes it���ll help close the sale. We hit the ball in the water, decide we know more than the golf pro and go back to our old swing. And we, and those we love, suffer.

I know I���ll never become a great golfer or the richest man in the world. But if I keep learning, asking for help and focusing on doing the right things, I suspect my golf score���and other parts of my life���will continue to improve. And if you happen to see a 63-year-old dancing around an 88-year-old on the 18th hole, cut me a little slack.

Don Southworth is a semi-retired minister, consultant and tax preparer living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. He recently completed his Certified Financial Planner education.�� Don is passionate about the intersection between spirituality and money, and he encourages people to follow their callings wherever they lead.��Follow Don on Twitter @Calltrepreneur . His��previous articles were Magic Number,��Answering the Call and��Twin Certainties.

The post Don’t Be Your Results appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 3, 2021

Why We Struggle

Ask any doctor the recipe for good health and you’ll hear the same things: Exercise regularly, eat right, don’t smoke. It isn’t complicated—and yet it isn’t so simple. Environmental factors, genetics and bad luck conspire against us. Result: Even the most disciplined person isn’t guaranteed perfect health.

It’s the same with personal finance. We all know the basic formula: Start early, save consistently, keep costs low. Again, it seems simple. And yet somehow the path to financial success is far from simple. Why is that?

In 1940, a young Wall Street broker named Fred Schwed wrote a book titled Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? It was satire, but it rang true. The premise: The brokerage industry’s lavish fees allow stockbrokers to buy yachts. But because of those fees, clients aren't able to afford yachts for themselves.

Schwed’s observation is less true today. The cost of investing has come down significantly. And yet personal finance still isn’t easy. Why is that? Fees, it turns out, weren’t the only problem. They definitely were—and continue to be—part of the problem. But I’ve noticed at least nine other obstacles that regularly get in the way of success:

1. Behavioral finance is at least as important as quantitative finance, but it's harder to teach. In recent years, behavioral finance has received more attention and is better understood. But understanding the problem only gets us partway toward solving it. The challenge is that the behavioral finance literature, excellent as it is, offers very little in the way of solutions. What can you do? Read as much as possible about market history—Charles Kindleberger's book Manias, Panics, and Crashes, for example. I also recommend the work of University of California at Berkeley professor Terrance Odean, an expert on investor behavior, including the paper he recently co-authored on Robinhood.

2. The financial world is almost infinitely complex. To make sense of the world, however, our minds are programmed to simplify—and often to oversimplify. When it comes to the complex world of investments, that’s a problem. What can you do? In the past, I’ve talked about Robert Shiller's book Narrative Economics. I've also mentioned Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's concept of the single story. They're similar ideas. I recommend reading about both to gain a better understanding of this pitfall.

3. Financial salespeople take advantage of complexity. If anyone has ever tried to sell you a whole life insurance policy, you know what I mean. The industry continues to cook up increasingly complex instruments. These products can be tricky for two reasons: It’s hard to know how a complex investment will behave under different market conditions—and complexity can obscure high fees. What can you do? Keep it simple. If someone tries to sell you a newfangled investment, challenge them to explain how it would be superior to simple investments like stocks, bonds and real estate.

4. The government hasn't made it any easier. Our tax laws are a thicket, one that’s constantly shifting. What can you do? There's no way to know what Congress will do next. But there's still value in proactive planning. If you have an accountant, I recommend sitting down with him or her during the summer, when your accountant is likely less busy. Go over last year's tax return and ask for his or her observations and recommendations.

5. No one can see around corners—but some pretend they can. Turn on the TV and you’re bound to hear an investment “strategist” talking about the market. What can you do? This one may be the easiest to address. Whenever you’re tempted to listen to an investment prognosticator, just think back to last year, when the coronavirus came out of nowhere, knocking the economy into recession. No one saw that coming. And no one can predict what will come out of left field next. Instead, build a plan that doesn’t rely on short-term market predictions.

6. Stock-picking is even more difficult than it appears. The most surprising finance paper ever to cross my desk was titled “Do Stocks Outperform Treasury Bills?” Authored by Hendrik Bessembinder, a professor at Arizona State University, the paper concluded that just 4% of all stocks accounted for all of the U.S. stock market’s gains over and above Treasury bills over a nine-decade stretch. The other 96%, as a group, have delivered returns no better than humble Treasury bills.

What can you do? In today’s market, where some investors have scored big wins on Tesla and other highfliers, you might feel like you're missing out. If you’re ever tempted to jump into the fray, though, keep Bessembinder’s research in mind. The odds of beating the market are exceedingly small.

7. Investment markets are the master of the head fake. If markets were either fully rational or fully irrational 100% of the time, life would be easier for investors. The problem is that the market is rational just often enough to fool us into thinking it’s logical. We saw that, for example, when tax rates were cut in 2017. But just when it seems like the market makes sense, it goes completely haywire. We observed that last spring, when stock prices dropped to irrationally low levels. What to do? I always stress the importance of asset allocation. This is the only way, in my opinion, to protect yourself from a market that’s sure to deliver its fair share of curveballs.

8. Risk is a critical concept, but investors don’t even agree on how to define it. Some investors believe standard deviation is the best measure of risk. To support their view, they point to Nobel Prize-winning research. But others, including Warren Buffett, believe standard deviation is worthless. As an individual investor, this can be confusing.

What to do? I’m with Buffett—I think standard deviation is a flawed concept. But in fairness, risk does take many forms, making it elusive. My recommendation: Focus on the most important risk, which is the risk that you suffer a shortfall in meeting your financial goals. Then structure your portfolio accordingly. If you want to learn more, I recommend William Bernstein’s book Deep Risk and Howard Marks’s The Most Important Thing .

9. College tuition has become a wrecking ball. Back in 2017, I related the story of a young college graduate whose life had been hijacked by crushing student loans. In my work with clients, I see this over and over. The cost of college in the U.S. has been rising at double the rate of inflation or more for decades. What can you do? There’s still a positive return on investment for some colleges. But as a consumer, you need to be more careful than ever. If you have school-age children, I recommend Ron Lieber’s new book The Price You Pay for College to help you think more critically about the college question.

Latest Articles

HERE ARE THE SIX other articles published by HumbleDollar this week:

"Giving away 10% is a constant reminder we have enough—even when we’re afraid we don’t," writes Don Southworth. "It’s hard to explain the sense of joy I've experienced from trusting there’s enough to share."

How do you find the right college, asks Anika Hedstrom? You need to figure out what your kid wants—and then dig into the numbers to find which colleges offer it and at what price.

If you own long-term-care insurance, you likely get letters every year announcing premium increases. Those are aggravating—but they're also a sign you're getting a good deal, says Adam Grossman.

When you leave fulltime work, you lose daily contact with colleagues. How will you replace that? During his semi-retirement, James McGlynn has discovered four new communities.

When he retired, Dennis Friedman hired a financial advisor. But he wonders whether he'd be better off with a low-cost target-date retirement fund.

What caught readers' attention last month? Check out the seven most popular articles published by HumbleDollar in June.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.

Adam M. Grossman is the founder of Mayport, a fixed-fee wealth management firm. Sign up for Adam's Daily Ideas email, follow him on Twitter @AdamMGrossman and check out his earlier articles.The post Why We Struggle appeared first on HumbleDollar.

July 2, 2021

It’s Who You Know

I grew up in Fort Worth, Texas, but moved throughout my career. Fifteen years ago, I returned to Texas and���as part of my relocation���"pioneered��� working from home. I���ve spent the past few years reconnecting with classmates from elementary school through high school, meeting them individually for lunch and using Facebook to arrange annual mini-reunions. I���ve known some of these folks for more than 55 years.

Another community I found is the local monthly American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) meeting. I joined the group four years ago. At age 61, I���m the youngest member. The average age is probably 75 and perhaps older.

Before the pandemic, we met monthly at a restaurant, before switching to Zoom when COVID-19 hit. The conversations aren���t all about the stock market and generating retirement income. Currently, I���m quizzing the other members about their experience with cataract surgery.

The third community centers on pickleball. It���s one of the fastest growing sports in the country���a combination of tennis, badminton and ping-pong that can be played by all ages. According to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association, pickleball participation grew 21% during the pandemic. Because the sport is relatively new, the games are usually played on converted basketball or tennis courts.

In addition to providing an excellent cardio workout, the sport is very social. Pickleball is popular among retirees, so games are often available during what would otherwise be the workday. It���s also popular among both genders. I���ve competed against teenagers and those in their 80s. I���m so enamored of the game that I���ve taken to proselytizing, trying to persuade my old classmates to take up the sport as they enter retirement. For those of us who remember watching Jimmy Connors, John McEnroe and Bjorn Borg as kids, it's like going to recess every day.

The fourth community is traveling plus volunteering. One overseas group I found is Angloville. In return for free room and board at a desirable hotel or resort, volunteers have conversations in English with Polish speakers who want to learn English. Many Poles learned German and Russian growing up, and now are learning English later in life.

Two years ago, I did this for a week and I���m still in touch with a couple of the Polish students. Instead of just traveling to another foreign country, I was able to spend a week with a group of locals who wanted to learn English���and my only requirement was to speak slowly enough to be understood. There were English-speaking volunteers from Hong Kong, Canada, New Zealand, Britain and Australia, as well as the U.S. When the pandemic abates in Europe, I plan to return to Eastern Europe to travel inexpensively���and meet new and old friends.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of

Next Quarter Century LLC

��in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of��

Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers

. Check out his earlier articles.

James McGlynn, CFA, RICP, is chief executive of

Next Quarter Century LLC

��in Fort Worth, Texas, a firm focused on helping clients make smarter decisions about long-term-care insurance, Social Security and other retirement planning issues. He was a mutual fund manager for 30 years. James is the author of��

Retirement Planning Tips for Baby Boomers

. Check out his earlier articles.The post It’s Who You Know appeared first on HumbleDollar.