Jason Micheli's Blog, page 8

June 15, 2025

The Now Done Darkness

If you appreciate the work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

This Trinity Sunday, I began a summer sermon series on the miracles of Jesus by preaching on 2 Kings 4.8-37.

Ponder a question.

Is it possible, in principle, that all events could be predicted by means of the laws of nature? That is, if you knew all physical laws perfectly— from Newton’s Three Laws of Motion to the First Law of Thermodynamics to Maxwell’s Equations— and also could see the total state of the universe at any given moment— a God’s eye view, then would you be able to predict all future events? In other words, is the creation nature?

Is the world a machine?

It’s not just a question for quantum physicists and philosophers.

It’s a crucible for Christians.

After all, does not every prayer ask for a miracle?

On the tenth day of Christmas this year the esteemed New Testament scholar Richard Hays died after a decade-long bout with pancreatic cancer. Seven years ago— three years after doctors confidently predicted his death— Hays, addressed those who had gathered to celebrate his retirement from Duke Divinity School.

At the top of his lecture, Hays said,

“I’m grateful to all of you who’ve come here this evening to hear a few reflections from me on the occasion of my retirement. I’m grateful for all your prayers over these past three years.”

They worked.

God answered them.

With a miracle.

“I’m grateful for all your prayers. Most of all, I’m grateful to God for granting me a miracle— a little more world and a little more time— to think back on what has been and to ponder what is to come. The key note of all I have to say is gratitude. This is the day that the Lord has made. Let us rejoice and be glad in it.”

This is the day the Lord has made. That’s not a sentiment. It’s a claim.

Hays continued:

“Most of you know…three years ago I received a devastating diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, and I went on medical leave to undergo chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. When I left the dean’s office that July, I left in tears with my hair falling out. I took up the tasks of reviewing my will and writing directions for my funeral service. As I stand here tonight, I’m unexpectedly able to look back on that night, that year, of now done darkness. Chastened, hopeful, healed. I’m grateful for your prayers.”

On Friday in Greenwich, Connecticut I presented an essay in honor of my mentor Fleming Rutledge. The occasion marked the fiftieth anniversary of her ordination in the Episcopal Church. During seminary, I delivered mail to her while she was in residence at Princeton’s Center for Theological Inquiry. For twenty-five years her preaching and friendship have sustained me in both my ministry and in my illness. During a break in between speakers on Friday, Fleming embraced me like a drowning woman clutching a rescue buoy. When she let go of me, she laid her palms on my shoulders and she inquired about my health, marveling that the return of my cancer had not prevented me from traveling to the surprise celebration Wycliffe College had convened for her.

After updating her on my treatment and its side effects, Fleming recalled an evening in Durham a decade ago when Richard Hays— that same renown New Testament scholar— took her out for dinner and informed her about his recent, grim diagnosis. Fleming’s immediate response was to hold her hands outstretched over the candle on the restaurant table. Grasping his hands, she implored him, “We must pray, Richard!”

“I’m not a very good prayer,” the New Testament scholar confessed.

“I’m not a very good prayer either,” Fleming replied, “Nevertheless, we must pray for a miracle.”

And so they did, urgently and unselfconsciously in front of the restaurant’s staff and patrons. They prayed for more than moments. They prayed long enough and loud enough to make the other customers uncomfortable. Why should their prayers have discomfited the other patrons? Because most people answer yes to the question with which I began. Most people live in the world as though the world is a machine.

Remembering their petitions, Fleming peered into my eyes and said, “I don’t know if it was because of our prayer or the prayer of another who loved Richard, but I do know his survival was the LORD’s doing. God gave him ten years more time. It was the grace of God. It was the breath of Jesus Christ. It was the Holy Spirit. It was miraculous.”

Then she threw her arms around me again, tight and unyielding.

And she preached into my ear, “I pray every day that the LORD may do so for you as well. I pray that God would grant you a miracle.”

The problem with preaching on the miracles of Jesus is that we imagine his miracles are isolated to the years of his public ministry, in places like Jericho and Capernaum and Nain. But when the Risen Jesus pours out his Spirit at Pentecost, he pours his Spirit not simply on the believing community but onto all of creation. The Risen Christ not only breathes his Spirit onto his disciples in the Upper Room, he breathes his Spirit into the whole world.

His breath just is the might rushing wind.

Christ’s crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension make room in God for us. The Holy Spirit’s descent at Pentecost makes room in us for God. When Jesus promises the Holy Spirit, he promises that, through the Spirit, God will fill all things with himself. And remember! One of the creatures upon which Jesus sends his Holy Spirit is time. At Pentecost, the Holy Spirit enshrouds more than the diaspora pilgrims in the temple courts. It descends upon and it fills even Israel’s past.

The Risen Jesus sends his Spirit not just down but backwards.

Into time.

In other words, only because of Pentecost does the Holy Spirit alight upon the lips of Israel’s prophets. Only because the Word was made flesh and raised from the dead can they speak the Word of the LORD. And Elisha can breath upon a mother’s boy in Shunem, bringing him back from the dead, only because Jesus breathes his Spirit onto his disciples. Therefore, as much as the crippled man at the pool of Bethsaida or the over-served guests at the wedding in Cana of Galilee, the Shunammite woman’s son is every bit a miracle performed by Jesus.

The Shunammite woman— we never learn her name— knows this is a miracle performed by the LORD Jesus even if she knows not the name of Mary’s boy.

Notice—

When the prophet Elisha first passes through Shunem with his servant Gehazi, she calls him the “Man of God,” which is more than a generic religious title because she immediately commands her husband to build onto their home an upper room. And she instructs her husband to place in the upper room a bed, table, chair, and a menorah— exactly the same furnishings as in the Temple in Jerusalem: the lamp stand of the sanctuary, the table of the presence, and the space of rest where God’s presence dwells.

She’s building a little Zion for the Man of God!

This is why Elisha speaks to the Shunammite woman through an intermediary, the “priest” Gehazi just as only the high priest enters into the Holy of Holies on behalf of the people. And this is why the Shunammite woman pays homage to Elisha on Sabbaths and news moons and why she brings Elisha their first fruits.

When the mother of the boy sees the prophet Elisha, she correctly sees an accompanying power and an abiding presence that rightly belongs enthroned in the LORD’s Temple.

As the theologian Peter Leithart writes:

“What Israel normally expects at the Temple is available from Elisha. What Israel normally expects to do at the Temple, they do in the presence of Elisha. He is a “protoincarnation,” so much so that his title “Man of God” could as easily be rendered as the “God-Man.”

Of course Elisha can raise the dead.

He has the Holy Spirit of Jesus.

In 2019, at the United Methodist Church’s General Conference in St. Louis, I finished one night sharing a drink with my friend Bishop Will Willimon. After bemoaning the costly, slow-motion divorce renting the denomination asunder, Will shared with me how the day before the proceedings began all the members of the Council of Bishops were divided into small groups to share “God sightings” and to pray for one another.

“I got seated with a couple of bishops from the left coast,” Will said, “a few others from blue areas of the country and a bishop from Nigeria.”

Will took a sip of his bourbon and smiled.

“When it came time to reflect on where they had seen the LORD at work in their ministries, the progressive bishops all talked about work that needs not a Risen Lord to do—efforts at inclusion in their part of the church or justice work their congregations had engaged.”

He finished his drink and laughed.

“And then this bishop from Africa spoke up and he said, “A member of one of my churches died, and the entire congregation— the whole community— prayed over him all night long. I arrived the next morning. By then, his body was cold. But they prayed again. I prayed with them. And the man sat up and lived.”

“And then the bishop looked at his American colleagues,” Will said, “and he asked them with total innocence and complete sincerity, “Do you not have any miracle stories?”

Will motioned for another round and smiled, “It was just wonderful the way he made those liberal, educated preachers stare at the floor, squirming in their functional atheism.”

When the prophet Elisha promises the Shunammite woman a child, she does not laugh like Sarah laughs in the Book of Genesis, dismissing it as an absurdity. She does not respond with disbelief like Zechariah does in the Temple when he’s told he will father John the Baptist. She does not even inquire about the impossibility of such a promise like Mary so inquires with the angel Gabriel.

The Shunammite woman instead says to Elisha, “No, my lord, O Man of God, do not deceive me.”

Don’t lie to me.

It is not that she does not believe the LORD can work miracles. She knows enough to have remodeled her house and added a Little Zion next to the Man Cave. It’s not that she does not believe in miracles. It’s that she’s already prayed for that miracle. And the LORD did not make it so. Don’t lie to me. She did not receive the miracle for which she had prayed; subsequently, she made peace with her life. Now the prophet’s promise threatens the contentment she had found with the life she had accepted.

Don’t lie to me.

I can’t bear the thought of my prayer not getting answered again.

But she does not laugh like Sarah! She knows that nothing is impossible with God! She knows what too many of us have forgotten. She knows she inhabits a world that is not a machine. She knows that the Maker of Heaven and Earth is not only the author of history but an actor within it. Indeed his Holy Spirit sometimes sleeps upstairs in her Upper Room. Just so, she knows that not only can the LORD address us, he may be petitioned by us. That is, she knows that she lives in a world where prayer makes a difference. And because God listens, miracles can happen.

Notice what the Shunammite woman does and does not do when her son dies in her lap. She does not scream. She does not weep or wail. She does not despair. She does not even tell her husband. She’s a wealthy woman, but she doesn’t call a village doctor. She does not say a word to anyone.

She lays her dead boy down.

Where?

On the bed. In the “temple.” The Holy of Holies.

She doesn’t prepare for a funeral.

She doesn’t sit shiva.

She doesn’t cry or scream.

She saddles a donkey.

And then goes straight to the Man of God.

Or more accurately, she hastens to the Holy Spirit who abides with Elisha but resides in the Temple.

After her boy dies, as she’s saddling her ride her unknowing husband asks her why she’s setting out to see Elisha, “Why will you go to him today? It is neither new moon nor Sabbath.” And the only words she says to her husband, “All is well.”

All is well.

It’s going to be alright.

It is not that she grieves not. It is that she knows the kind of world in which lives. She knows this is the day that the LORD is making. And she has an opinion about what God ought to do with it.

She saddles her donkey and she neither weeps nor laughs.

She knows—like Jacob knew at the river, like Moses knew on the mountain, like Hannah knew at the temple—that God can be petitioned. That the LORD of Hosts can be wrestled, can be implored, can be held to his promises.

She doesn’t go to Elisha for counseling.

She goes to Elisha— she goes to the Spirit of Jesus— for resurrection.

As the story of the Shunammite woman shows, questions about miracles are really questions about prayer— petition. Which is to say, the philosopher David Hume’s problem of miracles is a problem of prayer. And both— questions about miracles, questions about prayer— are best answered by still another question, “What does it mean to be a creature?”

To be a creature is to live within the freedom of God.

To be a creature is to live within the freedom of God.

If we believe in the power of prayer, if we believe in the possibility of miracles, there are two ways of accounting for them.

On the one hand, we can “follow the science.”

We can affirm that God is (was) the Maker of Heaven and Earth and the world is a machine. Thus, all natural processes have a deterministic character to them. Natural laws are laws absolutely. Gravity always wins. Miracles, as well as the prayers that petition for them, may be described as limitations of natural law. Miracles and prayers then squeeze God’s freedom into the “gaps” of the physical laws and the natural order. In other words, an answered prayer or a miraculous event are discrete instances of God glitching his own designed system.

On the other hand, we can take Jesus at his word, “If in my name you ask me for anything, I will do it.”

We can regard the reality of prayer and miracles as itself what the theologian Robert Jenson calls "a metaphysical axiom.” That is, all natural events— the universe and the galaxy, a quark and a hearer of this sermon, a manhunt in Minnesota and a No Kings protest near the Swiss Bakery— they all occur in “the creative actuality of the Spirit.”

In other words, prayer and miracles are always possible because after Pentecost everything— every event— is inhabited by the Spirit who lodged in the Shunammite woman’s Upper Room.

If there is not the God of the Bible, then events in the world and in our lives are either fixed or random.

But!

As Robert Jenson writes:

"Since there is the Spirit as one of the Trinity [the events of the world and the events of our lives] constitute the spontaneity of created events. The difference between regarding the dynamics of the world-process as random and regarding them as spontaneous may not be significant for empirical research, but it is decisive for our life as creatures in creation. If the dynamics of creation are a spontaneity, then events happen not mechanically but voluntarily, not on the basis of a system but according to a will …If this spontaneity is opened by the Spirit, then when we confront any actual or possible event we confront someone's freedom.

And believers claim to know that Someone.

Therefore prayer (for miracles), to come to the religious point, is simply the reasonable thing to do. For the process of the world is enveloped in and determined by a freedom, a freedom that can be addressed. What is around us is not iron impersonal fate.

As for miracles, the true problem is therefore not whether they are possible, but how we are to distinguish them from events in general. There is nothing more in the miracle than in the least of ordinary facts. But also there is nothing less in the most ordinary fact than in the miracle. That we are shocked into seeing this is the very intent of miracles.”

Back to the question.

If you knew all physical laws perfectly and could see the total state of the universe at any given moment— if you knew all the algorithms— then would you be able to predict all future events?

No.

Of course not.

Because creation is not a realm in which determinism rules; creation is a realm in which the Spirit of Jesus Christ rules. What is all around us is the Spirit of the Risen Jesus.

The Shunammite woman—

She does not laugh like Sarah laughs.

She does not doubt like Zechariah doubts.

She does not ponder the particulars of an impossible promise.

“It’s going to alright,” she tells her husband.

We do not know the Shunammite woman’s name, but we do know that she knows that the world she in which she lives is not a machine. She knows that the borders of our lives are not fixed by death. She knows she lives in a world governed not by fate but by providence, by the freedom of a persuadable God.

“I pray every day that the LORD may do so for you as well,” Fleming said to me, “I pray that God would grant you a miracle.”

And she does so pray.

On the train ride home, I reread her emails to me over the past months.

On March 3, she emailed me this prayer, “May our Lord, who suffered so terribly in public with no one to help him, comfort and strengthen you, especially if and when you feel you can't go on.”

On Christmas Eve, she sent me another prayer.

“Email is a poor substitute for presence,” she wrote, “You are having a Christmas season radically different from what you had expected just a few weeks ago. You and your family are continually in our God-directed thoughts. Dick is not very articulate these days given his dementia, but he shows a lot of emotion about things he cares about and he was shocked and distressed to hear the news. When we pray for you he is still able to utter a heartfelt "Yes" for you to be upheld. I pray the may make himself known to you many times each day.”

In January, she offered a short prayer, “LORD, we do not know what the future holds, but we trust that this is the day you are making and if it be your will make this cup pass from our friend. Dick and I trust that you are able to make a way out of no way.”

The Risen Jesus sends his Spirit not just down but backwards.

And forwards.

Into our time.

On Monday I visited my oncologist for my monthly labs and examination. And my blood work and my body exam came back sufficiently good that my doctor cancelled the PET scan that was scheduled for next month.

“These drugs are a miracle,” he said.

We throw that word around, miracle.

He looked surprised when I said, “Amen.”

“The true problem of miracles is therefore not whether they are possible, but how we are to distinguish them from events in general.”

I am grateful for all your prayers. Most of all, I’m grateful to God for granting me a little more world and a little more time. This is the day that the Lord is making.

The Shunammite woman knows the structures of reality are not impervious to divine interruption. She knows nature is actually creation and therefore the world is not a machine.

She knows this because she has practiced hospitality to the presence of God. She knows this because she has made a room for the prophet, the one who speaks on God’s behalf and acts in the Holy Spirit of Jesus. She knows this because her little Zion has a table.

And so does ours.

“Do you not have any miracle stories?” the African bishop asked his colleagues.

Of course you do.

Every Sunday, week in and week out, in our ordinary little temple, God gives nothing less than Christ himself to you in his Gospel word. Week after week, the LORD is here at table, hiding not behind a bald prophet named Elisha but in creatures of bread and wine.

The gospel word, wine and water and bread— they are proof that what is around us is not iron impersonal fate or algorithms that can account for your every move. The gospel word, wine and bread— they are proof that God is not nowhere in the world.

The sacraments are tangible, visible signs of the Shunammite woman’s words, “It’s going to be alright.”

So come to the table. You don’t even need a donkey— he’s right here. To come to the table is to seek the Holy Spirit. Come, taste and see the LORD is good! Even when it feels otherwise.

Come.

Receive this miracle as a downpayment on the miracle for which you pray.

And remember—

Because Jesus is not dead, he is free to surprise us.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 13, 2025

The Syntax of Salvation

If you appreciate my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

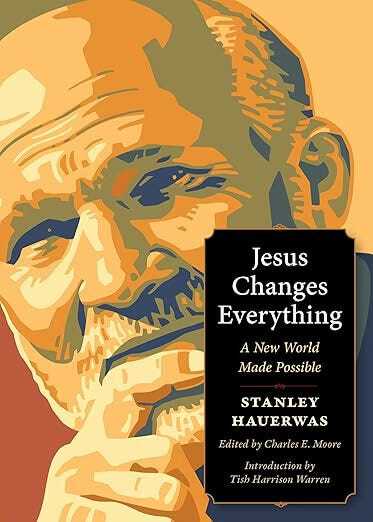

It was my honor to participate in the Celebration of Fleming Rutledge at St. Barnabas Episcopal Church in Greenwich, Connecticut. Convened by Wycliffe College in Toronto, where Fleming once taught preaching, the celebration was in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of her ordination. We also used the occasion to announce a forthcoming volume of essays in Fleming’s honor (a Festschrifte) to which I will be contributing. I am humbled to be included with the likes of Will Willimon, Stanley Hauerwas, Katherine Sondregger, Joe Mangina, and Jason Byassee.

It was truly a joy to see how God has drawn people together from across traditions and ages through Fleming’s preaching and writing, and it was an even greater blessing to witness how deeply moved she was at all those who had traveled or sent video tributes to express gratitude for her work.

In fact, Fleming is a subscriber to this Substack so I would encourage you to use the comments section to express your own appreciation for her work and preaching.As always, I began my offering with a prayer, but this prayer was not my own prayer but a prayer Fleming prayed on an old episode of the podcast.

“Lord take away our self-consciousness.

O Lord our God, heavenly Father, great Creator, Father of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, teach us again, and again, that this is your word to us, that it is not only your gigantic voice of command that parted the waters, but your intimate whispers to us, calling our names, setting us in our place, making the ground firm under our feet as we navigate the troubled waters of our world, never more so than now.

Make that ground firm under our feet as we listen to your voice, speaking to us through the pages of this, your Word of God written. Help us to listen for your voice and to set aside the voices of others who disbelieve, cast dispersions, mock, undermine our faith. Help us to find the right places to look for the fathers and mothers of the faith who read the Scripture with awe and wonder.

Give us that faith, Lord, again and again.

Give us the ears of little Samuel and the humility of the prophets who knew they could not do in themselves what they were called to do. Let us hear your Word. Amen.”

I was a teenager about to attend Dick Rutledge’s University of Virginia.

And I was a reluctant churchgoer, cynical towards the world generally and sneering towards the faith especially. I was about six months into my mother’s mandated worship attendance when I came forward, like so many other ordinary Sundays, down the aisle, hands held out like the beggar I refused to believe I was, when suddenly, for a moment, like a rip of lightening, the hands tearing off pieces from the loaf were no longer the hands of the man I knew to be named Steve Chiocca. Nor was the body to which those hands belonged his body.

I cannot say how I knew.

I simply knew.

I knew it was Jesus.

“This is my body, broken for you,” he said— out loud? In my head?

There were holes in the hands that placed the bread in mine. It terrified me. And it made me a believer. It’s probably the only thing that could’ve made a cynic like me into a believer.

Not long after, when I started the process that led to ordination as a pastor, I learned not to tell that story. Clergy, ironically enough, were the quickest to think I was crazy and ask if I’d sought counseling. I begin with that mystical memory in order to attest that I believe the apostolic witness— I believe Jesus Christ is risen from the dead because I have met him.

I have met him.

Not only have I met the LORD, I have heard him speak.

I have heard the Word of the LORD.

And I have so heard through no more reliable means than the preaching of Fleming Rutledge.

As a student at Princeton Theological Seminary, I delivered mail to Fleming Rutledge when she was in residence at the Center for Theological Inquiry. Much like my interactions with the theologian Robert Jenson, I was intimidated by the matchless preacher’s urgency of purpose and intensity of faith. Despite my awkward mumbling, she turned even momentary pleasantries into opportunities for public proclamation of the gospel. I serve as the Preacher-in-Residence for a Lily-funded endeavor called the Iowa Preachers Project. One of the lessons we have imparted to the cohort of young preachers is that the charism of ordination means that every interaction, in and out of the pulpit, is a preaching opportunity. On more than one occasion, while I handed her mail to her, she had a word for me.

Again, I believe Jesus Christ is not dead because I have heard him speak.

Through Fleming Rutledge.

As a rookie preacher, I mined The Bible and the New York Times like an apprentice looks over a potter’s shoulder. During my second pastorate, I emptied my continuing education fund to enroll at the College of Preachers to study under her. Like a boy with a crush, I fawned over her at a conference held at Christ United Methodist Church in New York City. I count it providential that she said yes to an invitation to join my friends and I on our podcast; I count it grace that through those conversations a faraway mentor became a dear friend.

In saying this, I risk sentimentality, which she would loathe. So let me underscore my point once more. Fleming Rutledge is dear to me because through her I have heard the voice of the LORD Jesus Christ who “upholds the universe through his word of power.”

I begin this essay proper, then, as Fleming Rutledge might begin— from the pages of the “Gray Lady.”

Cyrus Habib lost his sight as an eight-year-old boy in Seattle, Washington. A rare cancer afflicted his eyes and forced the removal of his retinas. Habib spent the ensuing decades working to prove to the world and to himself that he could accomplish anything he fixed his mind on. He matriculated at Columbia University where he subsequently won a Rhodes Scholarship. A JD followed from Yale Law School. “From Braille to Yale” was how Habib often described his inspiring journey. Until a few years ago, Habib, who was still only thirty-seven years old, he was serving as Lieutenant Governor of Washington State. And according to the New York Times, in March 2020, Cyrus Habib announced to voters that his name would not be on the ballot that November.

Rather than seek a second term, an election he was projected to win handily, Habib announced that he had decided to become a priest. Or rather, as Habib clarified the matter, he had been summoned to become a priest. Instead of climbing the ladder to ever greater political power and prestige, Habib said that he would be entering the novitiate in Los Angeles to begin an intensive ten year ordination process that included vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. As Father James Martin told the New York Times, “he'll have a dramatic change of life from being lieutenant governor to being told he's cleaning the bathroom in the wrong way.”

Habib told the New York Times he feared the very same can-do attitude that equipped him to overcome his blindness could also, now that he was ensconced in power, be his undoing. “If hardened into an ideology of its own,” he said, “it can crowd God out because it makes you into a kind of God. And it says, I'm not a contingent creature. I'm completely independent.”

“Stepping down,” he told the Times, “it's like giving your car keys to someone before you start drinking.” Cyrus Habib says God called him to the priesthood while he was in negotiations over a book deal. “I was in talks with a top literary agent in New York,” he said, “and it was all predicated on my biography, my identity, my story.” He said it struck him that if God is at work in the world speaking and calling and convicting, summoning into existence things that do not exist, then our individual stories cannot really be said to be our stories.

“Can they?” he said.

Just like that, God made a blind man see.

When it comes to the gospel of Jesus Christ— the word of the cross that is the word power— I believe the syntax of that previous sentence makes all the difference.

God made a blind man see

God healed him.

Not: The blind man regained his sight. Not: The blind man reconsidered his situation. Not: The blind man came to see himself in light of God's mighty claim upon him.

No.

Cyrus Habib told the Times, “It struck him.”

God made him to see.

In his 2001 Gifford Lectures, Stanley Hauerwas draws upon Karl Barth's conviction that the form of our speech is intimately related to our understanding of God. “Language,” Hauerwas argues, “creates and conditions thought.” This includes, I would insist, our understanding of the Word of God. A proper appreciation for the Spirit that inhabits the scriptures, I believe, demands that we attend to the sentences we speak, whether we're behind a podium or in a pulpit or in a hospital room.

If God’s Pentecost project to make all things new necessarily includes his calling preachers to proclaim, then the difference between medicine that makes alive and a placebo that is pretense alone comes down to the matter of subjects and verbs. In case you might judge me as overly persnickety about the syntax of salvation allow me to point out that I am in good company. As Fleming Rutledge observes, Augustine took note of the subtle way in which Pelagius sought to upend the gospel by the addition of a mere adverbial phrase, “more easily.” As you know, Pelagius argued that by the help of the Holy Spirit we can more easily resist evil. “Now why,” Augustine slyly, “why did he insert that phrase “more easily?””

Augustine continues:

“Pelagius wants it to be supposed that so great are the powers of our nature, which he is in such a hurry to exalt, that even without the help of the Holy Ghost, evil spirits can be resisted. Less easily it may be, but still in a certain measure. The addition of the words “more easily” tacitly suggests the possibility of accomplishing good works even without the grace of God."

Thus, Augustine illustrates how the arrangement of words in a sentence can mean the difference between a sinner being made a new creation or being left dead in their trespass.

It was not on the syllabus, but I learned this lesson twenty five years ago at Princeton Theological Seminary. I was part of a captive audience for a class on preaching. I was captive in the worst kind of way because this belligerently confident, hyper-evangelical classmate preached his "sample sermon” before the homiletics class.

“I have been working on this sermon my whole life,” the student said before praying in a manner condemned by the LORD in Matthew 6.

Our homiletics professor, Dr. James Kay, looked restless and irritated throughout the entire twenty minute sermon. And once the sermon was finally over, Dr. Kay looked exasperated. It was not the reaction the beaming student preacher had anticipated.

"Do you realize,” Dr. Kay thundered with genuine offense, “not one of your sentences had God as the subject?”

The professor’s point seemed completely lost on the preacher.

“God was not the subject of any of the verbs in your sermon,” he explained. “If the gospel is true, then you don't need any I’s in your sermon. The living word is able to work what the word says.”

It was a mic drop moment before mic drops were memes.

As a young preacher, I felt liberated to hear that there need not be any I’d in the sermon. My stories, my beliefs, my spiritual experiences, my religious insights. Not if the living God is a loquacious LORD, determined to reveal himself at work through his word to bring us to himself. Obviously, this is an argument Fleming Rutledge has often advanced.

She makes the same argument by pointing to the example of Paul, who while dictating his letter to the foolish Galatians, catches himself mid-sentence to rearrange his syntax according to the gospel. Paul stops mid-sentence in order to exchange the object for the subject. He writes in chapter four, “formally when you did not know God, you were in bondage to beings that by nature are no gods. But now that you have come to know God, or rather to be known by God. How can you turn back again to the weak and beggarly elemental spirit?” “The strange new world of the Bible,” Karl Barth first wrote, “does not describe the human being's journey upwards to God.” In fact, despite the ubiquity of journey language in the church, as becomes clear to any reader who spends time in the scriptures, the Bible's plot is quite the opposite.

The Bible reveals God's relentless prodigal journey down the up staircase in search of us, “Adam, where are you?” That's the summary statement for the plot line of the entire Bible. The difference between God being the subject of our sentences rather than the object of them is thus the difference between sermons which are anthropological and sermons which are theological.

As Fleming Rutledge argues:

“Preachers today tend to go against the grain of the Bible, both Old and New Testaments, because we have been conditioned to shift out of the theological mode and into the anthropological mode, which means nothing less than setting the world of the Bible aside…I sometimes wonder how Peter would feel about being the subject of so many sermons…We have been deeply influenced, whether we know it or not, by the imperatives we have heard to make the sermon meet people where they are. But if we do that, we leave little room for the cloud-rending Word to speak.”

Where others did not, Karl Barth keenly perceived that only the latter, only theological sermons which took revelation as their basis and beginning, only those sermons were immune from the otherwise incisive critique of Ludwig Feuerbach, who chided Christians that all our God talk is but puffed up stained glass speech about ourselves.

My friend Dennis Zulu is a clinical psychologist, and he likes to remind preachers of the faith what his guild knows empirically, “We are all strangers to ourselves.” Nevertheless! Because the LORD of heaven and earth has both a Mother and an Executioner, preachers know more about God than we do ourselves. We know more about God than we do any political issue or current event. We know God better than we do our listeners.

Sermons should have sentences with God as the subject, Barth counsels us, because God is the only sure foundation of knowledge that we possess in this world. Moreover, only this syntax conveys the biblical claim that we are incapable of journeying to God— even if we wanted God, which the scriptures make fairly clear we don’t. A living God alone who is the active agent of all the sentences that make up our lives, only that God can cure what truly ails us. Exactly because Mary’s boy and Pilate’s victim is God, we know there is no longer any possibility for a positive synthesis between human religious striving and divine grace. Anthropological preaching presumes the possibility of a synergism inexorably invalidated by the incarnation and crucifixion of the Son of God.

With God demoted to the object of our sentences, Fleming Rutledge argues, sermons can no longer be charismatic.

As Robert Jenson notices in a study of Romans 8, in announcing the decisive turning of the ages in Jesus Christ, the apostle Paul’s argument functions by positing a double opposite to the Spirit, “flesh” and the “law.” The “law of sin and death” just is “the Law” absolutely. But “the Law” is also a mode of God’s word. That is, the Law is opposite to Spirit. But the Law is also God’s first word.

Just so, in this argument the Spirit includes— the Spirit is synonymous with, equivalent to— what Paul elsewhere calls “promise” or “the gospel.”

In other words, the Spirit is the power of the promises called gospel. The Spirit is the power of the gospel preachers have been summoned to proclaim. The Spirit is God’s second word. At the pivot point in his epistle, the apostle Paul uses Spirit language to repeat what he announced at the outset, “For I am not ashamed of the gospel, for it is the power of God.”

As Fleming Rutledge writes in Proclaiming the Lord Jesus Christ:

“If the preacher preaches as though the LORD Jesus Christ is living and active, like the Word described in Hebrews 4.12, the power of the Holy Spirit will inhabit the speaker’s words— not because the speaker is eloquent but because, as the LORD himself promises, “He will glorify me, for he will take what is mine and declare it to you.” We need to depend not on homiletical theories and devices but on the assurance of the Word of God that it will authenticate itself.”

Thus, sermons afraid to make God the subject of the verbs are no more powerful than inert TNT.

Back in the winter of 2021, just after the insurrection, Fleming Rutledge sent me a text message.

“If this not a circumstance in which the true church can take only one position, I don’t know what one would be,” her first text read.

She quickly followed with another message:

“If this is not a time of status confessionis, I don’t know what is. If this is not a time for courage in the pulpit, I can’t imagine what that time would be. From the sermons I’ve watched online, all I have found is studious avoidance of the Big Lie. Jason, you must risk not being liked and take seriously your responsibility to the Lord to preach and teach the truth in this Empire of Lies. If we continue to live in an Empire of Lies and never speak out, never bear witness to the kingdom, never dare to live the difference Christ makes, we simply give lie to Paul’s promise of the Spirit’s presence with us.”

To make God the subject of the verbs, the preacher must possess not a little eschatological nerve. Similarly, in her Parchman Lectures on Preaching, Fleming Rutledge diagnoses an ailment afflicting the mainline church.

She writes:

“Sermons tend to be timid. They lack a sense of urgency. Preachers seem to be afraid of too much power. I think mainline preachers have become so reluctant to be mistaken for evangelicals that they have been in full flight in the other direction.”

If the apostle’s promise is true, if the Spirit and the gospel are one, then the power preachers fear is God. It is therefore no wonder that we push him to the end of our sentences just as we pushed him out of the world on a cross.

In an address at Wycliffe College, Rutledge concludes:

“Now finally, I will admit that all of this talk of sentences and verbs may give the wrong impression. Very few people are blessed with exceptional literary or rhetorical gifts. And most students of preaching today cannot be expected to rise to the standards of eloquence that were commonplace in earlier centuries. But there is no one who, in declaring the gospel message, cannot learn to make God the subject of active verbs. It is a form of trusting in the God who speaks. None of us can be John Donne, but we can all make a sentence like, “The author of salvation is God.”And we can all learn to avoid sentences like, “We are all on a faith journey.” And we can instead declare that “God has sought us and found us.”

I concur with Fleming Rutledge that anthropological sermons are limp and honestly not worth waking at an inconvenient hour on a Sunday morning. Meanwhile, preaching that minds the wisdom tradition exclusively, the practical, advice-giving messages that are so popular in the American church today, is likewise impotent and not worthy of the apostle’s absence of shame of the gospel. Such wisdom sermons are grossly dubious on theological grounds. After all, if I could follow such practical advice and be the sort of person it commends, I need neither Jesus nor his church.

Quite simply, those sorts of messages are ultimately not nearly as compelling as the God who is still a Jew from Nazareth, having lived briefly and died violently and rose unexpectedly. In the end, Solomonic tips on being a better parent just aren't as interesting as a preacher who dares to tell me that not only am I not a perfect parent, I nailed God to a tree.

The word of the cross is more than power.

It is inherently, infinitely interesting.

However—

However, the more I work with the word, the less I believe in practicing what Dr. Kay preached that afternoon in the Princeton classroom. The more I preach to sinners— broken by the world and sometimes by the church— the more I want to push beyond Fleming Rutledge’s emphasis on the subject of verbs.

Kay and Rutledge are both absolutely correct that we are not the good news, which is the best news. We do not need to fetter God's word with our own subjectivities. Nonetheless, after a quarter of a century preaching every Sunday, after sinning every day, after living with incurable cancer for a decade, after years of not just proclaiming to my congregation but learning to love them, I am convinced— I have been convicted— that preaching does not become proclamation without an I.

Preaching does not become proclamation without an I.

In fact, there does need to be an I in our sermons.

The sermon is no different than the sacrament.

Every message needs an I and a for you.

Preaching needs to be more than theological or even charismatic.

Preaching needs to be eschatological. Yes.

God is on the move, at work in the world— yes, but the one place God has promised to be found is in a particular word that first spells the death of you. The sermon, as Robert Jenson writes, must be an existential crisis, an address that ends you and makes you Easter new. And for that event, that encounter to occur, you need not a word about God, but a word from God.

The actuality of revelation, what Karl Barth emphasized as an antidote to liberal anthropology, must be actualized in the lives of people who hear and believe.

Sermons that are simply about God are sermons still stuck in the third person. Rather than using texts to talk about what God might be doing in the world, preachers must do the text to their hears. For this is a doing that God has promised to be up to in the world.

The pulpit is not a platform.

It is a doing.

It is a doing of God, just as surely as if God had torn a hole in the roof of a church and lowered the listeners down one by one on a stretcher.

For sermons to be eschatological, for preaching to rise to proclamation, preachers must make themselves the subject of some sentences and dare to utter an unflinching promise on behalf of the God who has called them. Such a first-person promise requires the absolute conviction that though I am the speaking subject, the active agent at work is altogether not me.

In order to pay for law school, a former parishioner of mine signed on to serve as an Army JAG officer. Back when he was still studying torts and constitutional law, he expected that one day he would be dealing with divorces and drunk-disorderly charges. He never dreamed he'd find himself in the middle of the worst of the second Iraq war, daily navigating land mines and IEDs and suicide bombers.

All these years later, he's still in shock.

I remember him leaving worship one Sunday after hearing a scripture passage from the sermon on the Mount. In the narthex, he described to me, in frightened but a dispassionate affect, the anticlimactic sound a human head makes when a homemade suicide vest ignites.

“She didn't look old enough to drive,” he told.

And without stopping his story, he then said to me, “That's the problem with you, preacher.”

“The problem with me?” I asked.

“You talk about loving our enemies, but you don't get it. You don't understand. You're starting from the wrong place. You're starting with us too many steps down the board. Where I'm at, I don't even want to want to love my enemies.”

And he paused and he stepped back to look at the effect of his words on me.

“What do you have to say about that?” he asked.

And I thought about it, turning the keys that Christ has given us over in my hand. There's a time for binding a listener in their sins. And there's a time for loosing them. And to discern between the times is an art. There's a way to bind that takes sin seriously without also making grace conditional and thus slightly less amazing.

And so I said to him, “What do I think about that? I guess I'd say that that makes you God's enemy.”

And as sudden as a car backfiring, he broke down.

And after a while, I put my hand on his shoulder and I said, “Worship is over, but I'm not so sure I finished the sermon. So let me get it done now for you, Casey.”

I looked him in the eyes, “Casey, in the name of Jesus Christ, I promise you. You are forgiven for your sins.”

“All of them?” he asked.

And I nodded.

“Someone like you with the hate you have in your heart, you have no hope outside the gospel.”

And I waited a couple of beats.

“But you have nothing but hope inside the gospel.”

And he looked at me with skepticism.

My lack of eschatological humility embarrassed him.

“But what gives you the right? How do you know? Who are you to speak for God?”

“It's actually my job," I said, “God called me to speak for him, and God is present to you in this promise here and now in this musty narthex, as sure and certain as you were standing in the garden on Easter morning.

And he smiled.

And then he laughed the most wonderful laugh.

In the Gospel of Mark, both Jesus' acts of healing and his declaration of the forgiveness of sins, elicit a question that is equal parts faithful and flummoxed, “By what authority?”

Where does this guy get off?

What gives him the right?

Who died and made him God?

To his eventual antagonists and murderers, Jesus' willingness to make declarations on God's behalf was the kind of infringement that constitutes a violation of the sacred boundary. My former teacher, the Markan scholar Donald Juel, summarizes the response to Jesus' preaching and healing ministry with two words, “Jesus blasphemed.” For preaching to be proclamation, preachers must take the risk and be liable to the very same accusation, “Who are you to speak for God?” Such a risk is necessary because the Great Physician has a peculiar way of healing his patients.

I remember when I was first diagnosed with incurable cancer ten years ago. I wasted time on the cancer ward losing myself down rabbit holes on Wikipedia and WebMD. I discovered that chemotherapy owes its origins to the use of mustard gas in World War I. Not only was mustard gas a nasty little way to debilitate your enemy, it was also discovered to be an effective suppressor of blood production.

“We're going to stop just short of doing you in permanently” I remember my oncologist informing me with the unchecked glee of a black site interrogator, “That’s your only chance to live.”

With his two words, Law and Gospel, God goes all the way.

He does the deed to us.

“I kill and make alive,” God declares in Deuteronomy.

“I form light and create darkness. I make weal and create woe. I, the Lord, do all these things,” the Lord declares to the prophet Isaiah.

"He has made us sufficient to be ministers of a new covenant, not of the letter, but of the Spirit, for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life,” writes Paul.

If the spirit's work is to give life to those whom the letter has killed, then clearly the Healer dispatches us as heralds to do more than present information and insight to our hearers. Obviously, the LORD intends that those who gospel do more than offer hearers possibilities for a decision. Plainly, it is not enough for public proclaimers to retell the scriptural passage. If we have only exposited the text, explaining its historical context and recommending contemporary implications, then as Karl Barth might say, we have not yet dared to preach.

If we have no I’s in our proclamation, we have not yet dared to preach.

As friends of the Friend of Sinners, preachers must do more than speak about the text to hearers. We must do the text to them. And in this respect, Jesus is the perfect homiletical role model, “You have heard that it was said, you should not commit adultery. But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman with lust has already committed adultery with her in his heart."

Proclamation aims beyond a summary of the text's meaning.

Proclamation aims for a repetition of the effect of the text on its first-hears.

Preaching does the text to them so as to render Christ’s effect to them.

This means hermeneutics is important to homiletics, not to interrogate the preacher's contextual particularities and interpretive prejudices, though that's important, but to understand how best to wield scripture against listeners, wounding them and binding them in a manner consistent with the way that the text first convicted and comforted its hearers. In other words, a good check on every word we speak as pastors is the question, “What in this speech is such a foolish stumbling block it might motivate my hearer to pick up a hammer and crucify me?” If the proclamation doesn't put me in the place of Caiaphas or Pontius Pilate, I don't ever really get to be Peter, thrice forgiven on the very beach in Capernaum where Christ first called him.

The function of a passage’s words are every bit as essential therefore as their content. The prophet Nathan's preaching to David is, I believe, the Bible's exemplar sermon. After catching the sinner in a story much like his own, the preacher Nathan declares to the king, “In the name of the Lord, I say unto you, you are the man.” “Apart from the foolish, gratuitous mercy of God, your goose is cooked,” Nathan all but says. As it happened with David, human sin ends when proclamation of Christ and Him crucified, taken from a text, is done to the hearer in the here and now.

This is riskier than three points and a poem.

This requires more nerve than positing biblical principles for marriage or exhorting listeners to stand up for this cause or that cause, often causes they would support even if they were not Christians. There is no room here for “I am just a seeker on a journey with fellow pilgrims.”

A more distinct category than preaching: proclamation is eschatological address. Proclamation is eschatological address in that it recapitulates the effect of the text. And what the text always does, overtly or subtly, is convict and promise. Accuse but give mercy. Kill and make alive.

Quite simply, it is safer for the preacher to explain than proclaim.

If there is no other cure for what ultimately ails us, then people have no other choice but to show up at church and pray that the pastor knows what to do. This would be a terrifying burden to lay on preachers if preaching depended upon preachers. Proclamation requires the same eschatological nerve that preachers display at the table and the font. The same God who hides in creatures of bread and wine, clothes himself in the absolving, empowering word of the gospel on the lips of a sinner called to preach.

When you grasp this promise called gospel in faith, you have nothing less than Christ himself.

Just marvel at the mystery and the mercy of it.

To give this promise is to offer him.

The assertion that God's two words possess the power to mortify and vivify not only points out that pastors have been given a very particular task to execute with their words. It also presumes that God is the active agent of their speech. My mere words might be able to do more damage than sticks and stones, but they can't raise anyone from the dead. If God is the one who addresses hearers in the here and now, then proclamation has no other intelligible mode than for the preacher to speak not about God, but for God.

As the theologian Gerhard Forde insists:

“In the attempt to explain God, proclamation loses out. God becomes such a patsy that he no longer really matters. Preaching then has no point. There is one truthful answer to the question, “Whatever happened to God?” It is this, Jesus. Because Jesus happened to God, we are authorized and commissioned to speak for God. To preach for God, not to explain or offer opinions about God. Wonder of wonders, we can actually deliver what God says.”

See—

Just as teaching is not preaching, preaching is not necessarily proclamation.

While preaching can include categories such as exhortation and catechesis and apologetics and instructions on discipleship, proclamation is more comprehensive because it occurs also in the sacraments and in the liturgy, in the pastor's office and at the hospital bedside, in everyday Christian conversation as much as in the pulpit, by laity as much as by preachers.

The difference between proclamation and preaching is the difference between primary and secondary discourse. Too often our churches sound like classrooms or counseling centers, giving off the distinct impression that the mighty acts of God have long since ceased. Primary discourse is the present tense, first to second person, unconditional promise authorized by Jesus Christ to which the only logical response is shock and repentance, love and wonder.

How could the Living God’s address of you yield to any other response than repentance and love and wonder?

I often hear believers in Fleming Rutledge’s Episcopal Church say “Well, at least in my church, even if the sermon is dreadful, I still get the gospel in bread and wine.” I think this is a more instructive comment than we give it credit. It's not just that the sermon leads to the table. It's that the table provides a template for what proclamation looks like. We do not stand behind the loaf and the cup and explain or describe or exhort or offer secondary discourse. We give Christ, present tense, first to second person, here.

“I'm handing him to you, the body of Christ broken for you.”

What preachers say in far too many sermons, on the other hand, and in everyday Christian speech, is so often at odds with the proclamation we speak in the sacraments.

“But you just clothed that baby in Christ's righteousness. What are you doing in your sermon making it sound like there's work they've got to do to earn what was just given free of charge?” I thought to myself mid-sermon only a few Sundays ago.

Proclamation keeps Christ from the appearance of giving two contradictory words, from the table and from the pulpit or the pastor's office. Now I wonder— I wonder if the abiding appeal of the Eucharist is that the sacrament forces the preacher to be a giver and it frees the hearer to be a beggar.

I heard the theologian Jim Nestingen lecture on proclamation and the gospel at an event years ago. During his presentation, he shared a story about how he'd been traveling long hours and many miles from conference to conference. “I hate traveling,” he said, “and I despise airplanes. When you're my size, riding on an airplane is like doing penance. I don't hardly fit on any of them.”

"I was flying coast to coast in a long flight,” he said, “and I got on this plane and of course, every airline's policy, wouldn't you know it, but the guy sitting in the seat next to me was every bit as big and fat as me. We buckled up as best we could and got ready for takeoff. Sitting there on top of each other, I'm sure we looked like two heads on the same pimple.”

And then Nestingen continued:

“Since we were practically on each other's laps, it would have felt strange if we didn't visit with each other and chat the other up. As the plane was taking off, he asked me what I did for a living. I said to him, “I'm a preacher of the gospel.” Almost as soon as the words got out, he shouted back at me, “I'm not a believer.” He said it loud too, because it was takeoff and the plane was all noise. But the man was curious.

Once we got to cruising altitude, he started asking me about being a preacher. After a bit, he said it to me again, “I'm not a believer.” So I said to him, “Okay, but that doesn't change anything. He's already gone and done it all for you, whether you like it or not. The man next to me was quiet for a while and then he started talking again and at first I thought it was a complete non sequitur complete change of subject he started telling me stories about the Vietnam War he'd been an infantryman in the war and he fought at all the awful battles, Khe Sanh, the Tet Offensive, Hamburger Hill. He told me, “I did terrible things for my country and when I came home my country didn't want to talk about it. I’ve had a terrible time living with it. Living with myself.”

This went on the whole flight, from coast to coast, him giving over to me all the awful things he'd done. As the flight was about finished, I asked him, I said to him, “Have you confessed all the sins now that have been troubling you?”

He didn't just listen.

He didn't just say, I feel your pain.

He didn't, he didn't minimize it and say, “Well, what you were doing was just your duty. Don't be so hard on yourself.

He didn't dismiss it, “Sounds like PTSD”

He didn't deflect and say, “I'm here for you.”

Jim offered this man the medicine.

“Have you confessed all the sins now that have been troubling you?” “What do you mean confessed? I've never confessed,” the man replied. “You've been confessing your sins to me this whole flight long and I've been commanded by Christ Jesus that when I hear a confession like that to hand over the goods and speak a particular word to you. So you have any more sins burdening burdening you? If so, throw them in there.”

“I'm done now,” the man next to him said, “I'm finished.” And then he grabbed my hand. He grabbed my hand just like he had just a second thought. And he said to me, “But I told you, I'm not a believer. I don't have any faith in me.” I unbuckled my seatbelt and I said to him, “Well, nobody has faith inside them. Faith alone saves us because it comes from outside of us, from one creature to another creature. I'm speaking faith into you.”

And so I unsqueezed myself from the chair, and I stood up. The seatbelt sign had already dinged and the tray tables had been secured back in their upright positions and the seats were all back up and straight and proper, but I stood up over him. The stewardess then, she starts yelling and fussing at me, “Sir, sir! You can't do that. Sit down. You can't do that." And I ignored her, which meant pretty soon others around us were fussing and hollering at me too. “You can't do that. Sit down,” they said to me. “Can't do it,” I said to the stewardess, “Ma’am, Christ our Lord commands me to do it.”

And she looked back at me scared like she was afraid I was going to evangelize her or something. So I turned back to the man next to me and standing over him, I put my hand on his head and I said, “In the name of Jesus Christ and by his authority, I declare unto you the entire forgiveness of all your sins.”

“You can't do that,” the man said.

“I can do it. I must. Christ compels me to do it and I just did it and I'll do it again.”

So I gave him the goods again, Jim said. I tipped his head back and I spoke faith into him. I needed it loud for everyone on that plane to hear it, “In the name of Jesus Christ, you are forgiven.”

And just like that, the man started sobbing like somebody had stuck him. And his shirt was wet from all his weeping. It was like he'd become a little child again. And so I sat down and I held him in my arms like I'd hold a child.”

And then telling the story, Jim started to weep too.

He said:

“The stewardess and all the rest who'd been freaking out and fussing at me, they all stopped and became as silent as dead men. They knew, he said. They knew something more important was happening right now in front of them, something more important. This man's life was breaking open. Jesus Christ, by his spirit, was raising this man from the dead, from being dead in his trespasses right in front of them. And even if they didn't know to put it that way, they knew it was grace they were seeing. They knew it was holy.”

And telling the story, Jim looked out at the audience and he miled and he patted his Santa Claus punch and he said:

"After he stopped sobbing, as the plane was landing, he asked me to absolve him gain, like he couldn't get enough of the news. And so I did. And then the man wiped his eyes and he laughed and he said, “Gosh, if that's true, it's the best news I've ever heard. I just can't believe it. It's too good to be true. It would take a miracle for me to believe something so crazy good.”

“And I just chuckled,” Jim said, “and I told him, yeah, it takes amiracle for all of us. It takes a miracle for every last one of us.”

God made him see.

When I thought the story was over, Jim started to cry all over again.

And he said:

“After the plane landed, we were getting our bags down from the overhead compartment. I pulled my card out of my briefcase and I handed it to him. And I told him, you're likely not going to believe your forgiveness tomorrow, or the next day, or a week from now. When you stop having faith in it, call me and I'll bear witness to you all over again. I'll keep on doing it until you do, you really do trust and believe it.”

And then Jim laughed a big deep laugh and he said:

“Wouldn't you know it? He called me every day, every day, just to hear me declare the forgiveness of the gospel. It got to be he couldn't live without it. And I bore witness to it, to him every day, right up to the day he died.”

And then he said, and he paused before adding through his tears:

“I called him every day with it because I wanted the last words he heard in this life to be the first words he would hear Jesus himself say to him in the next life.”

That's proclamation.

That’s first person discourse.

That’s the absurd speech licensed by the Holy Spirit of God.

That’s a sermon that would not be a sermon without an I in some sentences.

In an old short piece for the Expository Times entitled “The Best Protein Diet,” Fleming Rutledge recalls:

“When I was in Edinburgh last spring, I was attracted to a church tucked back on a side street. It had a little home-made sign out front for Eastertide that said ‘Jesus is alive!’ That little sign drew me in because it proclaimed a living God.”

I know that Jesus is alive.

I know that Christ is risen indeed in no small part because I have heard him speak through Fleming Rutledge. In profound gratitude for the ways she has sustained me not only in ministry but in illness, I want to end with some sentences that have I as the subject.

Fleming—

In the name of Jesus Christ, by his authority alone and on the basis of his gospel, I promise you.

I promise you that your words have not returned empty.

I promise you that your words have worked what they said.

I promise you that all the evils and injustices you have studiously chronicled in your work will be rectified— God will make a way out of no way.

I promise you that the Prince of Lies, with whom you have forced us to reckon in our preaching, will finally be vanquished.

I promise you that though your grandchildren have not found the faith like you have hoped, they are not lost to the LORD but are known and loved.

I promise you that all your sins are forgiven.

I promise you that the One who will heal the nations will also heal the memory of your beloved husband, Dick.

And all of you who love Fleming Rutledge, I promise what only God can promise— in the New Creation, you will have yet more time with her. The One whom we have heard speak through her— you will, in the fullness of time, see face-to-face.

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

Get more from Jason Micheli in the Substack appAvailable for iOS and AndroidGet the app

June 12, 2025

God is Not a Noun

If you appreciate the work, pay it forward. Literally! Become a paid subscriber.

With Pentecost now our present everyday reality, this Sunday is the bane of many preachers and those who suffer them in the pews.

This Sunday is Trinity Sunday.

I have long thought the problem with preachers understanding and proclaiming God’s proper name is that seminaries tend to confine the Doctrine of the Trinity to Church History classes. Students thus receive the Nicene Creed etc as bold dates to be memorized for an exam rather than as providing the basic building blocks for speaking Christian.

In order to speak Christian, we must be able to articulate God’s proper name.That is, the Trinity is not a puzzle to be solved. It is a grammar to be spoken. And as Robert Jenson insists, it is the grammar of God’s own life.

Trinity is the grammar of God’s own life.

God is what happens when the Father sends the Son and breathes the Spirit. The Triune identity is not the sum of a math equation. The Triune identity is the summary of a narrative. The Trinity is thus not an explanation for God. The Trinity is simply the God who encounters us in the scriptures and speaks. In other words, the Triune identity is revelation. You cannot bring to the Doctrine of the Trinity an a priori, pagan conception of deity (“God is one”) and then attempt to shoehorn it into the Name above all names.

God is what happens when the Father sends the Son and breathes the Spirit.

June 10, 2025

The First Half of the Inheritance

If you support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Romans 8.17

Here is the sermon I offered for the “Preaching Slam” at the final gathering of the Iowa Preachers Project at Christ Episcopal Church in Charlottesville, Va. I was preceded by four very fine, faithful sermons by colleagues on the preceding verses of the lectionary epistle for Pentecost. Getting to know the members of the cohort this year has been a joy and a blessing. If I had a real job, I’d gladly sit as a lay person under Taran, Dennis, and Chip’s proclamation. And being reacquainted with a classmate from Princeton in Sarah Hinlicky Wilson is grace.

FYI:

Every sermon is delivered to particular ears.

In this case, this is a sermon primarily for preachers.

I wish to begin with an ending.

Ignatius Hazim was born in 1921 in a village near the city of Hama in Syria. The son of devout Arab Orthodox parents, Ignatius discerned a call to preach as a young boy. After having served for decades as an Orthodox priest, Ignatius became the Patriarch of Antioch in 1979. Just four years before his consecration, the World Council of Churches invited Father Ignatius to deliver a talk at their assembly in Nairobi. At the conclusion of his lecture, Father Ignatius proclaimed the following benediction:

“Without the Holy Spirit:

God is far away,

Christ stays in the past,

The church is simply an organization,

Authority is a matter of domination,

Mission is a matter of propaganda,

The liturgy is no more than an evocation,

Christian living is a slave morality,

The Gospel is a dead letter,

And preaching is futile.

But with the Holy Spirit:

The cosmos is resurrected and groans with the birth-pangs of the kingdom,

The risen Christ is here,

The church shows forth the life of the Trinity,

Authority is a liberating service,

Mission is Pentecost,

The liturgy is both memorial and anticipation,

Human action is deified,

The Gospel is living and active,

And preaching is the word of God.”

Without the Holy Spirit, preaching is worse than futile.

It’s dangerous.

In 2011, on the lips of Ignatius of Antioch, the gospel made enemies. The promise provoked conflict. Though he was an elderly man, the patriarch received attempts on his life simply due to his persistence in proclaiming the Prince of Peace at the advent of the Syrian Civil War.

If we are without the Spirit, then for our own good, we ought— like Jonah— to head to Joppa and board the first boat bound for the opposite end of the LORD’s call.

During the second war in Iraq, one week during Lent the LORD summoned me to preach about the use of state-sponsored torture. Newspapers had only recently begun reporting on the Torture Memos which documented the ghastly abuses at the prison in Abu Ghraib. The images outraged the world. In the face of such revelations, the churches in America were silent. Back then, I was young and brash and I proclaimed what I took to be self-evident. I still have the manuscript on a thumb drive that bears the teeth marks of my son, a toddler at the time.

“Why is the church in America so quiet these days?” I exhorted my hearers.

I let the question linger for an uncomfortably long silence before I continued:

“Why are Christians so quiet about this particular issue? What is the matter with us? Why is the church instead consumed with culture wars. Has the church lost its nerve? Has the church forgotten we worship a crucified Lord? No matter what a person has done or is suspected of doing, once that person is taken into custody, he or she becomes defenseless. The Old and New Testaments alike are clear: abuse of a defenseless person is an abomination in God’s sight. The defenselessness of a fetus is a central argument advanced against abortion. This conviction about defending the defenseless lies at the very heart of our faith. Yet we are silent, as quiet as all his followers who did not shout, “Do not crucify him!”

I did eventually hand over the goods. I delivered a promise. It was a gospel sermon. Nevertheless, as soon as I gave the blessing, a church member assaulted me in the narthex and, sticking his finger in my chest, he hollered at me, “Just where in the holy hell do you get off preaching like that, preacher?!”

I stammered.

“Well, Senator,” I said, “It is Lent and the LORD was tortured to death.”

The Chair of the Armed Services Committee shook his head.

He waved his finger at me, “You tell me, preacher— if Jesus was still alive do you honestly think Jesus would having anything to say about torture and the government?!”

“Um, well Senator, uh…I mean, he was crucified, I think...um...maybe he would have...” I started to say.

He shook his head and waved me off.

“Jesus would be rolling over in his grave if he knew you’d brought that kind of politics into our church! Just where did you get the idea that your liberal politics has any place in the church?!”

“He doesn’t have a grave…it’s empty…” I muttered to myself.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“Never mind,” I said.

He stood there, his hands on his hips, dandruff on his shoulders, waiting for me to answers.

Finally, he repeated his question, “Where did you get the idea that kind of politics has any place among believers?!”

I stammered, “Uh, I mean, it’s called the Book of Kings.”

He thought I was being cute.

“You better watch out!” he threatened, “I could have you run out of this place!”

“Bless your heart,” I replied.

He narrowed his eyes and held his holler to a whisper, “If what you believe about Jesus leads to such words, then I don’t see how you have any place here!”

And then he shook his now crimson head, motioned for his wife to catch up to him, and then he hurried off. A few weeks after, on Easter Sunday, when he arrived, opened up the worship bulletin and saw that I was the preacher, he turned right around and left the way he had come. By Pentecost a petition for the bishop to send me away had circulated through the congregation. A former chief of staff to the Majority Leader, the Senator knew how to whip votes. It took a distraction called cancer for me finally to forget the names that joined his petition.

Without the Holy Spirit, every preacher’s mouth should stay where Paul left them in Romans 3.19— shut.

Sealed in silence.

To the extent that believers in the mainline churches contemplate Pentecost at all, we tend to make of it either our primal institutional event (i.e., the “birthday” of the church) or the paradigmatic religious event (i.e., the eruption of mystical signs and wonders made possible by the Spirit’s outpouring). But in the context of St. Luke’s two volume narrative, the wind rushing through the upper room, the crackling of the tongues of fire, the startled voices rising outside the temple courts— including the voice of the one who first sang the Magnificat, with its lines about the proud and the powerful being brought low and the rich sent empty away— the signs of Pentecost all reveal the church’s political vocation. The fire and the wind and the wonder point neither to an institutional act nor to a religious experience but to a political event.

The signs of Pentecost all reveal the church’s political vocation.

From his triumphal entry into Jerusalem to his tear-laden lament over the same city, from the cracking of his whip in the temple to the crowd’s revolutionary acclamation of him, Luke’s account of Jesus’s life and death is overtly, unambiguously political. The charge nailed above his cross is the claim that erupts from his tomb. The Prince of Peace is King (of more than the Jews). That so many mistake Christ for his last name rather than his authority over all the world is an indictment of the church’s preaching.

That so many mistake Christ for his last name rather than his authority over all the world is an indictment of the church’s preaching.

For Luke, Pentecost vindicates Christ’s sovereignty and declares the persistence of his kingdom mission. As Peter makes clear in the very first gospel sermon— a sermon that sounds like too few of my sermons— the risen Christ, enthroned now with the Father, has declared war against God’s enemies.

To the bewildered crowd at Pentecost, Peter preaches:

“Being therefore exalted at the right hand of God, and having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, he has poured out this that you yourselves are seeing and hearing…“‘The Lord said to my Lord, “Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstool.””

The resurrected Christ has declared war against God’s enemies, and in pouring out the Spirit upon his disciples, he has authorized them as his envoys in this apocalyptic conflict. This is why Peter tells those who sneer at the Spirit, “We’re not drunk, yet; it’s only the third hour of the day.” And then he cites Joel, the prophet who proclaims “a new world order energized by the movement of the Holy Spirit, one which defies and promises to destroy the worldly orders” built on subjugation and exploitation. That which Peter calls in his sermon, “This crooked generation.” For Luke, the coming of the Spirit empowers the followers of the risen Christ— even slaves— to speak with God’s authority precisely in order to speak against God’s enemies.

Pentecost makes good on his mother’s words!

Since January, I have performed three weddings for couples concerned that one of them will be exiled to a gulag in El Salvador— that’s ridiculous. A theologian of the cross, Luther says, calls a thing a thing.

Just so—

Preachers of the cross have a word to bear against a world that builds crosses still.God created the universe through speech. The LORD called a contrast community by speaking. Jesus Christ “upholds the universe by his word of power.” And whilst he does so, the LORD Jesus is shaking the foundations, trampling his enemies underfoot, and making all things new through the selfsame means.

Words.

Your words.

But if they are merely your words, “we are of all people the most to be pitied."

Get thee to Joppa.

Back in the winter of 2021, just after the insurrection, the preacher Fleming Rutledge sent me a text message:

“If this not a circumstance in which the true church can take only one position, I don’t know what one would be.”

She quickly followed with another message:

“If this is not a time for courage in the pulpit, I can’t imagine what that time would be. From the sermons I’ve watched online, all I have found is studious avoidance of the Big Lie. Jason, you must risk not being liked and take seriously your responsibility to the Lord to preach and teach the truth in this Empire of Lies. If we continue to live in an Empire of Lies and never speak out, never bear witness to the kingdom, never dare to live the difference Christ makes, we simply give lie to Paul’s promise of the Spirit’s presence with us.”

Looking back at my sermons after Fleming grabbed me by my virtual lapels and shook me, I think “studious avoidance” captures my preaching better than “courageous.” I preached as though we are called simply to enjoy Christ’s benefits rather than share his vocation in making the right kind of enemies. I certainly wasn’t bold enough to dare use a phrase like “Empire of Lies.” I was not who she had reminded me that I am to be— who Pentecost makes me.

In her Parchman Lectures on Preaching, Fleming Rutledge diagnoses an ailment afflicting the mainline church.

She writes:

“Sermons tend to be timid. They lack a sense of urgency. Preachers seem to be afraid of too much power. I think mainline preachers have become so reluctant to be mistaken for evangelicals that they have been in full flight in the other direction.”

Or perhaps we fear not power but its aftershocks, the crater it leaves behind.